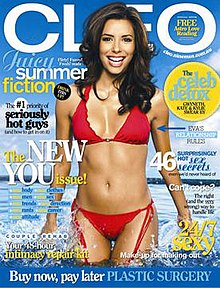

Cleo(magazine)

| |

| Editor | Lucy E. Cousins |

|---|---|

| Founding editor | Ita Buttrose |

| Categories | Women's Lifestyle |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Circulation | 53,221[1] |

| Total circulation | 173,000[2] |

| First issue | November 1972 |

| Final issue | March 2016 |

| Company |

|

| Country | Australia (published internationally) |

| Website | www.cleo.com.au |

Cleois an Australian monthly women's magazine. The magazine was founded in 1972 in Australia; the Australia and New Zealand editions were discontinued in February 2016. Aimed at an older audience than the teenage-focused Australian magazineDolly,Cleowas published byBauer Media Groupin Sydney and was known for itsCleoBachelor of the Year award.[3]In June 2020,Cleowas acquired by theSydneyinvestment firmMercury Capital.[5][4]

History and profile

[edit]Launched in November 1972[6]under the direction ofIta Buttrose,the magazine's founding editor,[7]Cleobecame one of Australia's most iconic titles due to its mix of seemingly controversial content, including the first nude male centerfold (following American Cosmopolitan's nude centerfold of Burt Reynolds six months' earlier) and detailed sex advice.

According to the magazine's editorial philosophy,"Cleo gets women, and it also strikes the perfect balance, offers a bright, light-hearted tone and aesthetic without shying away from the more serious issues that are important to their readers.".[8]

Audited circulation in June 2014 was 53,221 copies monthly.[9]Readership numbers for September 2014 are estimated to be 173,000.[2]

With a strong online presence of 300,000+ visitors monthly, the magazine successfully established its brand online. In addition, Beauty Bites,Cleo's digital app, offered an interactive component to technologically minded Gen Y readers, including how-to video tutorials, expert advice and reader-generated content.[8]

Cleo Singapore was launched in 1994, Cleo Malaysia in 1995, and Cleo Indonesia was launched in 2007 as an international license under the Femina Group.[10] Cleo Thailand operated sometime before 2014.[11]

Bauer announced on 20 January 2016 that the March issue ofCleowould be its last Australian edition.[12]

Launch

[edit]In the early 1970s, journalist and editor, Ita Buttrose, andKerry Packer,heir to what was then Australia's most influential publishing house,Australian Consolidated Press(ACP), created a new and bold Australian women's magazine which would become an instant sensation. Cleowas modelled in a large part onCosmopolitanafter the Packers lost the rights to the latter title to rivals Fairfax. The first issue was launched in November 1972, the same month thatGough Whitlamcame to power in Australia.

In the original promotional video forCleo,Buttrose observes "the rapidly changing personality of the Australian woman."[13]In an era when hopes for social and political change were high,Cleowas a fitting and welcome addition for women aged between 20 and 40 who were looking for something more than the recipes, knitting tips and coverage of royal births and weddings that theAustralian Women's Weeklyfocused on at the time.

Cleowas politically provocative (but not aggressive) with its journalism. Alongside articles on group sex, contraception, "happy hookers" andJack Thompsonas the first nude "Mate of the Month", the launch issue featured tips on "How to be a sexy housekeeper." In stark contrast to the lack of literary content in modern glossy magazines, Buttrose ran a short story byNorman Mailer,a prominent author at the time. This trend continued in subsequent issues.

In two days, 105,000 copies of the first issue were sold and by the end of its first year circulation reached 200,000. When the magazine conducted the first national readership survey in 1974, figures revealed that 30 percent of women aged between 13 and 24 readCleoevery month.[14]

Cleoas a form of popular feminism

[edit]ThroughCleo,feminism became a part of women's everyday lives and of their identity.

Ita Buttrose and her staff were committed to many of the ideas of women's and sexual liberation. However, it is important to note thatCleo's editorial agenda was that of liberal rather than radical feminism. In her first editorial letter, Buttrose described who she thought theCleoreader was:"You're an intelligent woman who's interested in everything that's going on, the type of person who wants a great deal more out of life. Like us, certain aspects of Women's Lib appeal to you but you're not aggressive about it."(1972).

The feminist tone and ideas proliferated on the pages ofCleothroughout the 1970s. Every month, there were feature articles covering issues including: the work/life balance, the pressure to get married and raise a family, abortion, contraception, women's education, domestic violence and rape. "The celebrities Cleo chose to interview were women who had succeeded in politics, business and culture. There were also discussions of the Women's Liberation Movement itself, with writers for and against".[15]

Ordinary, every-day women gained knowledge and understanding of feminism through the pages ofCleo.The magazine helped create the feminist public sphere, opening doors for discussions about new ideas which modern women treat as mainstream today.

Cleojump starts the sexual revolution

[edit]Cleopushed boundaries in mainstream publishing with candid articles on topics ranging from sex toys, fantasies and orgasms, to lesbianism and contraception. "We wrote about sex as if we had discovered it", recalls Buttrose.[16]

Cleowas the first Australian women's magazine to feature non-frontal nude male centrefolds in 1972, with Jack Thompson, a prominent Australian actor at the time, the magazine's first Mate of the Month. What Buttrose thought would be a light hearted, one-off feature became an essential component of what madeCleoso popular. Other mates were Alby Mangels, Eric Oldfield, Peter Blasina and the band Skyhooks. The centrefold feature was discontinued in 1985, the last being a bare-chested picture of Mel Gibson.

University of Sydney media academic Megan Le Masurier interprets the centerfold phenomenon as an incentive for popular feminist desire. The centerfold attempted to reverse the dominant tradition of representing men as viewers, and women as viewed. The representation of the male nude "offered women the chance to imagine themselves as active sexual agents, quite capable of holding the gaze".[17]The naked man was a reminder that women could, and should, enjoy sex, and reaffirmed their right to talk about sex.

Sex no longer sells

[edit]In 2013, new editorSharri Marksonannounced there would be no mention of sex on the cover ofCleo.More than 40 years after revamping women's magazines with male centrefolds, it was the first time that sex had not been used as a selling point.

The move came as a result of research conducted by the magazine which revealed a conservative streak among Generation Y readers –Cleo's largest audience demographic – most of whom still live at home.

As Markson explained: "They are embarrassed to be sitting at home with their parents reading a magazine which has the word 'orgasm' in bold print on the cover".[18]

In the pages ofCleo,all the racy content of the earlier, more progressive era was replaced with celebrity news and fashion, beauty and fitness tips.

Now sexy, according to December 2014 cover girl Taylor Swift is "knowing who you are and not needing to defend yourself."[19]

As seen through the pages ofCleo,there was a shift away from sexual liberation to personal gratification and self-improvement, a maxim characteristic of Generation Y.

Bauer: new owner, new direction

[edit]In October 2012, multinational publisherBauer Mediapurchased Australian magazine publisher ACP, which controls titles ranging fromCleomagazine toThe Australian Women's Weekly[20]This change of ownership meant drastic changes for the staff and readers ofCleomagazine.

Merge of editorial staff:DollyandCleo

[edit]A primary cost-cutting measure taken by Bauer was to merge the editorial staff ofDollyandCleomagazines, reducing the staff size by half and appointing a single Editor-in-Chief for both magazines.[21]

This was presented as a move to unite the two magazines under a "young women's lifestyles division".[22]

Observers argue that these two magazines are in fact not directed at the same generalised market. WhereDollytargets teenage girls,Cleofocuses on an older group, women in their twenties and thirties.[23]

Imported content

[edit]Bauer Media also now uses "content translated from Bauer's youth titles Joy and Bravo which the publishing house produce in Germany",[21]reducing the amount of original Australian content across the magazines, but reducing the cost of producing issues across their titles.

Lucy Cousins appointed Editor-in-Chief

[edit]In 2014, Lucy Cousins was appointed Editor-in-Chief of Bauer's newly mergedDollyandCleomagazines. Cousins was previously employed as Deputy Editor at Bauer's Women's Fitness magazine.[24]

Cousins says ofCleomagazine:

"CLEO magazine is and has always been a bible of all things fashion, beauty and celebrity for young Australian women. And now we've added travel, lifestyle, music and the new CLEO man section. We have attitude and aren't afraid to push the boundaries."[8]

Past editors' opinions on Bauer's changes

[edit]Mia Freedman:"Like most Australian women, Dolly and Cleo in particular were my lifeblood growing up and sparked my love of women's media back in the 80s and 90s. [I'm] frustrated and disappointed at the lack of business foresight that has brought those titles to this point. One of the reasons I left magazines was because I was so tired of trying to get my bosses to understand that Armageddon was coming in the form of online. I knew the young women's market was the most vulnerable. But nobody would listen so I left and started Mamamia...Publishers didn't realise they were content producers, they kept acting like magazine makers"[21]

Lisa Wilkinson on Twitter:"Very sad to hear news that Dolly & Cleo magazines are merging, with expected losses of half the staff. End of an era. And a personal one." Wilkinson believes that it will take"somebody who is an incredibly smart magazine editor and someone who understands the subtle but very important differences that are going to have to exist between those two magazines"to ensure the survival of bothDollyandCleomagazines.[23]

Readership figures 2013–14

[edit]It appears that Bauer's changes did not improve the continuing drop in circulation ofCleomagazine.Cleosuffered a steady decline in circulation due to changes in the way media was consumed and the failure of publishers in the 1990s and 2000s (decade) to follow their readers online. Statistics showedCleosuffered a 28.2% drop between September 2013 and September 2014, with a readership size of 173,000 in September 2014.[25]

Bauer Media however argued that it experienced a 100% increase in "social media growth" in that time period,[8]suggesting that indeed the reason why readership figures fell was due to the movement from print media to the online world of blogs, forums and Facebook. They also stated that the best that Bauer Media could do to ensure the continuation of Australian magazines likeCleowas to minimise its production costs and hope that it can catch up with digital media.

Final issue 2016

[edit]On 20 January 2016, Bauer Media Group confirmed thatCleomagazine would close in Australia after more than 40 years of publication, with the final issue being March, on sale 22 February.[12][26]Cleomagazine's final cover, for the March edition, would featureJesinta Campbell.

Mercury Capital acquisition

[edit]In June 2020,Cleowas acquired by theSydneyinvestment firmMercury Capitalas part of its acquisition of several of Bauer Media's former Australian and New Zealand titles.[5][4]

Noteworthy editors

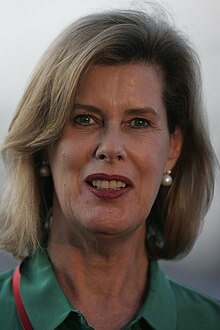

[edit]Ita Buttrose

[edit]

Ita Buttrosestarted as a copy girl at theAustralian Women's Weekly,she quickly became a cadet journalist atThe Daily Telegraphand its sister newspaperSunday Telegraphbefore taking over as women's editor at the age of 23. Buttrose would go on to become the first female Editor-in-Chief of these two newspapers and the first woman appointed to the board position withNews Limited.

Her arguably most well known role began in 1972, as the founding editor ofCleomagazine where she achieved such great success that it led to a promotion in 1975, editing the Packers' flagship magazine at the time, theAustralian Women's Weekly.She subsequently became editor-in-chief of both publications.

Buttrose played an important role in shaping women's identity in the 1970s through the pages ofCleo.She had the talent and conviction to take advantage of this period of social and political change, with new ideas about sexual freedom, female independence and gender equality heavily promoted in her magazine.

Despite scepticism fromSir Frank Packer,the Publisher, Buttrose's hunch thatCleowould appeal to modern Australian women proved to be right, with the magazine becoming the top selling monthly women's title and elevating Buttrose to the status of a feminist icon and magazine queen.

Andrew Cowell, the art director on the debut edition ofCleosaid: "Ita's always had a talent to tap into a real need. She's always been a forward thinker, which keeps her ahead of the curve and able to make instinctive decisions. If Ita had a gut feeling for something, you were best to go with it."[16]

Since 2011, Buttrose has been National President of Alzheimer's Australia and is also Vice-President of Arthritis Australia. In 2013, she was namedAustralian of the Year.Buttrose uses her high-profile to champion social issues such as women's education and raise awareness of breast cancer andHIV/AIDS.

Lisa Wilkinson

[edit]

Lisa Wilkinson's career in magazine publishing started at age 19 with no university education, as the enthusiastic secretary/editorial assistant/Girl Friday atDollymagazine. After rising to the editorship ofDollyin only 5 years, Wilkinson took over the position ofCleomagazine editor in 1984, and reigned there for ten years. Later she becameCleo's International Editor-in-Chief, running editions in New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. Under Wilkinson,Cleomagazine became the highest selling women's magazine per capita in the world.[27]

A significant change made by Wilkinson atCleowas the replacement of theCleocenterfold with the Bachelor of the Year competition in 1985.Cleomagazine presents an annual round up of the 50 most eligible bachelors in Australia, and encourages readers to vote for their favourite eligible bachelor.[28]

Wilkinson also mentored numerous high-profile women in Australian media today.Nicole Kidman,Miranda Kerr,Deborah Thomas,Paula Joyeand Mia Freedman all credit her as a long-time supporter.[27]

After her career as a magazine editor, Wilkinson established her own media consultancy business and hosted breakfast talk showTodayon the Nine Network, withKarl Stefanovic,before joining A Current Affair's programThe ProjectonNetwork Ten.[29]

Deborah Thomas

[edit]

Deborah Thomas' career in magazine publishing started atCleomagazine as Beauty and Lifestyle editor in 1987. She became deputy editor atCleoin 1990, and was editor at Mode (nowHarper's Bazaar) and Elle magazines until she took over the Editorship atCleofrom 1997 to 1999[30]where she "revive[d] the magazine's falling circulation and advertising revenue".[31]

AfterCleomagazine, Thomas became Editor-in-Chief ofThe Australian Women's Weeklyand was awarded Editor of the Year in 2002 for her efforts at the iconic magazine. Later, Thomas was Director of Media, Public Affairs and Brand Development across Bauer Media's portfolio of 70-plus titles.[32]In April 2015 she was appointed as CEO (chief executive officer) ofArdent Leisure.[33][34]

Mia Freedman

[edit]Mia Freedman's first foray into magazine publishing was also atCleo– doing work experience under then-editor Lisa Wilkinson.[35]Freedman became the youngest ever editor ofCosmopolitanmagazine at age 24,[36]and at 32 became Editor-in-Chief ofDolly,CleoandCosmo.[37] Freedman moved away from magazine publishing in 2007 and is now the publisher and editor behind popular women's interest websiteMamamia,while continuing to write articles and books across numerous publications.[38]

Sarah Oakes

[edit]Sarah Oakes is an experienced editor who has worked on a number of Australian publications such asK-ZoneandGirlfriendand received many accolades throughout her career. She was the youngest ever recipient of the Magazine Publishers' Awards, Editor of the Year Award in 2005. Oakes was the editor-in-chief ofCleobetween 2008 and 2010, where she repositioned the title and had great success with theCleo'Bachelor of the Year' campaigns. While atCleo,Oakes was also a finalist in the Good Editor Awards. Oakes currently holds the position of editor ofSunday Life,a Fairfax publication that has a readership of more than 1.6 million.[39]

Oakes' innovative changes forCleo

[edit]New editorial line-up

[edit]Oakes presided over the relaunch and repositioning ofCleoin October 2009. She has signed-up a veteran magazine editor and fashion stylist Aileen Marr as the new Fashion Director andPip Edwardsas Contributing Fashion Editor. The October issue in 2008 hence started to feature more fashion pages up front, introduce new sections and launch more beauty pages, including a market-first beauty panel.[40]Such a strong fashion editorial team cementedCleo's status as an invaluable source of information for women who want to stay on top of fashion trends.

"Models only" policy overturned

[edit]Oakes also brought celebrities back to theCleocover instead of "models only" policy introduced in the late 2007.

New "honesty policy"

[edit]Introduced in the August 2008 issue, this policy was designed to appeal to Generation Y, with readers invited to critique each issue in return for prizes such as iPhones and designer bags. As then editor Oakes explained, "Every month we will ask our readers online to give feedback (which will be) incorporated into the magazine the following month. We are doing all the things that motivate Generation Y: instant gratification and personalisation."[41]

Sales trend

[edit]Cleoexperienced an Average Net Paid Sales (ANPS) decline from 149,256 in 2008 to 134,286 in 2009, with a rate dropped by −10.03% and the number of copies sold decreased by 14,970-year-on-year.[42]Meanwhile, the cover price ofCleoincreased by $0.2 from $7.00 in 2008 to $7.20 in 2009. The circulation ofCleodecreased from 128,183 in 2009 to 110,081 in 2010.[43]

In popular culture

[edit]ABC mini-series,Paper Giants: The Birth of Cleodramatises the emergence of the magazine. Screened over two nights in April 2011, the series was a ratings winner, with an average of 1.34 million viewers tuning in on the opening night to watch Ita Buttrose (played by Asher Keddie) navigate the male dominated world of Australian publishing in the 1970s as she fights to getCleooff the ground.[44]For many avid readers ofCleo,the idea that the magazine almost did not exist made for exciting television.

Most critics praised Asher Keddie's convincing portrayal of Buttrose as an ambitious leader and supportive mentor. According to producer John Edwards, Buttrose was a significant contributor to the script. "When I went to meet her, she was tentative, nervous and fearful but also flattered".[45]

Feminist representational techniques

[edit]Academic Margaret Henderson argues that just asCleomade feminist ideas popular,Paper Giantsuses "feminist representational techniques" to make the 1970s era of social and political change accessible to modern audiences.[46]For many avid readers ofCleo,the idea that the magazine almost did not exist made for exciting television.

A feminist approach to relationships is shown through the many scenes of the staff gathered around the table brainstorming. The impression given is that the evolution of editorial ideas is very much a collective work process, and the women's relationship to each other is supportive rather than competitive.

The typicalCleoreader is represented by Ita's shy assistant, Leslie (played by Jessica Tovey) who begins the series faking orgasms and running errands, and by the end, escapes her dead-end relationship to begin working as a journalist in London.

Women's sexual liberation is highlighted in playful tones. There is plenty of joking, bantering, and double entendres among the female characters who use humour to deal with obstacles that come their way from the suits upstairs when creating the magazine. When we are shown the discomfort expressed by Kerry Packer (played by Rob Carlton) and Sir Frank when the female staff have frank discussions with them regarding the sexual content ofCleo,the scene is meant to be funny.

"Paper Giants' recruitment of humour…is an important corrective to the cliché of humourless feminists and to po-faced and hubristic accounts of radical political movements".[47]

CleoBachelor of the Year winners

[edit]- 2017 - Marcus Courts 21

- 2016 – Jaryd Robertson, 25

- 2015 –Matthew Buntine,22

- 2014 – Thien Nguyen

- 2013 – Trent Maxwell, 23

- 2012 –Hayden Quinn,26

- 2011 –Eamon Sullivan,25

- 2010 –Firass Dirani,26[48]

- 2009 –Axle Whitehead,28[49]

- 2008 –Jason Dundas,25[50]

- 2006 –Andy Lee,25[51]

- 2005 –Ryan Phelan,29[52]

- 2004 –Andrew G,30

- 2003 –Geoff Huegill,24

- 2002 –Paul Khoury,28[53]

- 2001 –David Whitehill,26

- 2000 –Craig Wing,21

- 1999 –Anthony Field,35[54]

- 1998 –Kyle Vander Kuyp,27

- 1997 –Kyle Sandilands,26

- 1996 –Eric Bana,28

- 1994 –Aaron Pedersen,24[55]

- 1993 –Grahame Smith,36

CleoNew Zealand Bachelor of the Year winners

[edit]- 2012 –John Templeton

- 2011 – Nick Oswald

- 2010 – Philipp Spahn[56]

- 2009 –please expand

- 2008 –please expand

- 2007 – Brad Werner[57]

- 1993 –Matthew Rodwell

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"Roy, EMMA and the ABCs".The Misfits Media Company. 15 August 2014.Retrieved9 January2015.

- ^ab"Australian Magazine Readership, 12 months to September 2014".Roy Morgan. Archived fromthe originalon 6 January 2015.Retrieved9 January2015.

- ^ab"Cleo magazine to close after 44 years in print, Bauer Media Group confirms".ABC News.20 January 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 8 November 2020.Retrieved3 September2020.

- ^abcWhyte, Jemina (19 June 2020)."Magazine buyer writes new story".Australian Financial Review.Archivedfrom the original on 23 June 2020.Retrieved17 July2020.

- ^abKelly, Vivienne (17 June 2020)."Bauer has left the building. What next for magazines in Australia?".Mumbrella.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020.Retrieved30 June2020.

- ^Robert Crawford; Kim Humphery (9 June 2010).Consumer Australia: Historical Perspectives.Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 59.ISBN978-1-4438-2305-0.Retrieved30 April2016.

- ^"Buttrose, Ita Clare (1942 - )".Australian Women's Register.Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved18 February2017.

- ^abcd"Cleo Magazine Overview".Archived fromthe originalon 9 January 2015.Retrieved9 January2015.

- ^"ABC Circulation Results – Aug 2014 Metropolitan Newspapers, All Magazines and NIMs"(PDF).ABC.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 9 January 2015.Retrieved1 January2015.

- ^"Cleo".SPH Magazines.Retrieved4 November2019.

- ^"CLEO Thailand Online Magazine - Cleo Thailand Magazine".www.cleothailand.com.Archived fromthe originalon 9 April 2019.Retrieved12 January2022.

- ^abABC 20 January 2016

- ^"Paper Giants: The Birth of Cleo Preview".ABC.

- ^Le Masurier, Megan (2010). "Reading the Flesh – Popular feminism, the second wave and Cleo's male Centrefold".Feminist Media Studies.11(2): 216.doi:10.1080/14680777.2010.521628.S2CID216643999.

- ^Le Masurier, Megan (2007). "My Other, My Self: Cleo Magazine and Feminism in 1970's Australia".Australian Feminist Studies.22(53): 199.

- ^abPitt, Helen (11 April 2011)."Ita Buttrose on kick-starting a sexual revolution".Retrieved10 January2015.

- ^Le Masurier, Megan (2010). "Reading the Flesh – Popular feminism, the second wave and Cleo's male centrefold".Feminist Media Studies.11(3): 226.doi:10.1080/14680777.2010.521628.S2CID216643999.

- ^Pickett, Rebekah."Cleo drops sex from front cover".The Fashion Section.Retrieved10 January2015.

- ^"Cleo magazine (Australia), December 2014".Taylor Swift Web Community. Archived fromthe originalon 14 April 2015.Retrieved10 January2015.

- ^Kruger, Colin (October 2012)."Bauer takes control of ACP".Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^abc"Q&A with Mia Freedman about the future of Dolly and Cleo".Mamamia. 13 November 2013.Retrieved7 January2015.

- ^"Bauer Media Group set to merge Cleo and Dolly teams".Mumbrella. 4 November 2013.Retrieved7 January2015.

- ^abHornery, Andrew."A sign of the times: Lisa Wilkinson laments changes ahead for Cleo and Dolly".Archived fromthe originalon 14 April 2015.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"Lucy Cousins appointed Editor-In-Chief CLEO & Dolly".Archived fromthe originalon 11 March 2015.Retrieved7 January2015.

- ^"Australian Magazine Readership, 12 months to September 2014".Roy Morgan. Archived fromthe originalon 6 January 2015.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^Jake Mitchell (20 January 2016)."Bauer confirms closure of Cleo".The Australian.Retrieved29 October2016.

- ^ab"Lisa Wilkinson".The Fordham Company.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"CLEO celebrates 25 years of Australia's Hottest List: 50 Most Eligible Bachelors".Archived fromthe originalon 14 April 2015.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"Leaders: Lisa Wilkinson".The Bottom Line. Archived fromthe originalon 1 March 2015.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^Jackson, Sally."Ten questions for Deborah Thomas".The Australian.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"Deborah Thomas".Australian Speakers Bureau.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"Deborah Thomas".ICMI Speakers.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^Burke, Liz (27 October 2016)."Dreamworld boss in line for $800k bonus".NewsComAu.Retrieved27 October2016.

- ^Daniel, Sue; MacMillan, Jade; staff (27 October 2016)."Dreamworld under fire for failing to contact victims' families directly".ABC News.Retrieved27 October2016.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^"Mia Freedman".Australian Speakers Bureau.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^Keenan, Catherine (23 August 2009)."Being Mia".Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"Mia Freedman".HuffPost.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"Mia Freedman".Small Business Big Marketing. 8 January 2013.Retrieved8 January2015.

- ^"In 2008 Sarah became editor of CLEO, where she repositioned the title".University of Canberra. Archived fromthe originalon 9 January 2015.Retrieved10 January2015.

- ^"CLEO relaunches and adds hot editorial team".Bauer Media Group.Archived fromthe originalon 9 January 2015.Retrieved10 January2015.

- ^"Cleo loses sealed section".The Australian.Retrieved10 January2015.

- ^"Australian Magazine Audit Report January to June 2009"(PDF).Mediabiznet.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 7 March 2011.Retrieved3 January2015.

- ^"Mags: State of the (mag)nation – December 2010 Circulation".Girl With a Satchel.Blogspot.14 February 2011.Retrieved16 January2015.

- ^Henderson, Margaret (2013). "A Celebratory feminist aesthetics in postfeminist times: Screening Paper Giants – The Birth of Cleo".Australian Feminist Studies.28(77): 261.doi:10.1080/08164649.2013.821727.S2CID143039508.

- ^Enker, Debi (13 April 2011)."Power and the passion: When women came of age".Retrieved10 January2015.

- ^Henderson, Margaret (2013). "A Celebratory feminist aesthetics in postfeminist times: Screening Paper Giants – The Birth of Cleo".Australian Feminist Studies.28(77): 260.doi:10.1080/08164649.2013.821727.S2CID143039508.

- ^Henderson, Margaret (2013). "A Celebratory feminist aesthetics in postfeminist times: Screening Paper Giants – The Birth of Cleo".Australian Feminist Studies.28(77): 258.doi:10.1080/08164649.2013.821727.S2CID143039508.

- ^AAP (29 April 2010)."Bachelor has fire in the belly".Herald Sun.Retrieved29 April2010.

- ^AAP (23 April 2009)."Axle Whitehead is Cleo bachelor of the year".The Age.Retrieved23 April2009.

- ^AAP (19 March 2008)."Jason Dundas named Cleo bachelor of the year".The Sydney Morning Herald.Retrieved27 March2008.

- ^Jacqueline Maley and Alexa Moses (15 September 2006)."Son, you be a bachelor boy".The Sydney Morning Herald.Retrieved4 August2007.

- ^"Bachelor of the year".The Age.16 September 2005.Retrieved4 August2007.

- ^"Airport manager our top bachelor".The Sydney Morning Herald.27 March 2002.Retrieved4 August2007.

- ^Christine Sams (5 May 2003)."Bride's something blue was a Wiggle".The Sydney Morning Herald.Retrieved2 August2007.

- ^"Biography for Aaron Pedersen".IMDb.Retrieved5 September2007.

- ^Bachelor of the Year 2010Archived4 June 2010 at theWayback Machine

- ^"CLEO bachelor of the year: Hot boys".Cleo Magazine.Retrieved10 December2007.

External links

[edit]- 1972 establishments in Australia

- 2016 disestablishments in Australia

- ACP magazine titles

- Mercury Capital

- Monthly magazines published in Australia

- Women's magazines published in Australia

- Defunct magazines published in Australia

- Magazines established in 1972

- Magazines disestablished in 2016

- Magazines published in Sydney

- Women's magazines published in New Zealand

- Multilingual magazines