Australia

Commonwealth of Australia | |

|---|---|

| Anthem:"Advance Australia Fair"[N 1] | |

Commonwealth of Australia

| |

| Capital | Canberra 35°18′29″S149°07′28″E/ 35.30806°S 149.12444°E |

| Largest city | Sydney(metropolitan) Melbourne(urban)[N 2] |

| National language | English |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Federalparliamentaryconstitutional monarchy |

| Charles III | |

| Sam Mostyn | |

| Anthony Albanese | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from theUnited Kingdom | |

•Federationand creation of theConstitution | 1 January 1901 |

| 15 November 1926 | |

| 9 October 1942 | |

•Australia Acts(complete independence from theUK Parliament) | 3 March 1986 |

| Area | |

• Total | 7,741,220[8][9][10][11][a]km2(2,988,900 sq mi) (6th) |

• Water (%) | 1.79 (2015)[12] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• 2021 census | |

• Density | 3.5/km2(9.1/sq mi) (192nd) |

| GDP(PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP(nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini(2020) | medium |

| HDI(2022) | very high(10th) |

| Currency | Australian dollar($) (AUD) |

| Time zone | UTC+8; +9.5; +10(AWST, ACST, AEST[N 4]) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+10.5; +11(ACDT, AEDT[N 4]) |

| DSTnot observed in Qld, WA and NT | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy[18] |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +61 |

| ISO 3166 code | AU |

| Internet TLD | .au |

Australia,officially theCommonwealth of Australia,[19]is acountrycomprising themainlandof theAustralian continent,the island ofTasmania,and numeroussmaller islands.[20]Australia is the largest country by area inOceaniaand the world'ssixth-largest country.Australia is the oldest,[21]flattest,[22]and driest inhabited continent,[23][24]with the least fertilesoils.[25][26]It is amegadiverse country,and its size gives it a wide variety of landscapes and climates, withdesertsin the centre,tropical rainforestsin the north-east,tropical savannasin the north, andmountain rangesin the south-east.

The ancestors ofAboriginal Australiansbegan arriving from south-east Asia 50,000 to 65,000 years ago, during thelast glacial period.[27][28][29]They settled the continent and had formed approximately 250 distinct language groups by the time of European settlement, maintaining some of the longest known continuingartisticandreligious traditionsin the world.[30]Australia'swritten historycommenced withEuropean maritime exploration.The Dutch were the first known Europeans to reach Australia, in 1606. British colonisation began in 1788 with the establishment of thepenal colonyofNew South Wales.By the mid-19th century, most of the continent had been explored by European settlers and five additional self-governingBritish colonieswere established, each gainingresponsible governmentby 1890. The coloniesfederatedin 1901, forming the Commonwealth of Australia.[31]This continued a process of increasing autonomy from theUnited Kingdom,highlighted by theStatute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942,and culminating in theAustralia Actsof 1986.[31]

Australia is afederalparliamentaryconstitutional monarchycomprisingsix states and ten territories:the states ofNew South Wales,Victoria,Queensland,Tasmania,South AustraliaandWestern Australia;the major mainlandAustralian Capital TerritoryandNorthern Territory;and other minor or external territories. Its population of nearly 27 million[13]is highly urbanised and heavily concentrated on the eastern seaboard.[32]Canberrais the nation's capital, whileits most populous citiesareSydney,Melbourne,Brisbane,PerthandAdelaide,which each possess a population of at least one million inhabitants.[33]Australian governments have promotedmulticulturalismsince the 1970s.[34]Australia isculturallydiverse and has one of the highest foreign-born populations in the world.[35][36]Its abundant natural resources and well-developed international trade relations are crucial to the country's economy, which generates its income from various sources: predominantly services (includingbanking,real estateandinternational education) as well asmining,manufacturingandagriculture.[37][38]Itranks highlyfor quality of life, health, education, economic freedom, civil liberties and political rights.[39]

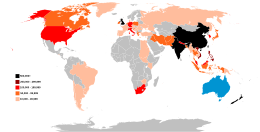

Australia has ahighly developedmarket economy andone of the highest per capita incomesglobally.[40][41][42]It is amiddle power,and has the world'sthirteenth-highest military expenditure.[43][44]It is a member of international groups including theUnited Nations;theG20;theOECD;theWorld Trade Organization;Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation;thePacific Islands Forum;thePacific Community;theCommonwealth of Nations;and the defence and security organisationsANZUS,AUKUS,and theFive Eyes.It is also amajor non-NATO allyof theUnited States.[45]

Etymology

The nameAustralia(pronounced/əˈstreɪliə/inAustralian English[46]) is derived from the LatinTerra Australis( "southern land" ), a name used for a hypothetical continent in the Southern Hemisphere since ancient times.[47]Several 16th-century cartographers used the word Australia on maps, but not to identify modern Australia.[48]When Europeans began visiting and mapping Australia in the 17th century, the nameTerra Australiswas applied to the new territories.[N 5]

Until the early 19th century, Australia was best known asNew Holland,a name first applied by the Dutch explorerAbel Tasmanin 1644 (asNieuw-Holland) and subsequently anglicised.Terra Australisstill saw occasional usage, such as in scientific texts.[N 6]The nameAustraliawas popularised by the explorerMatthew Flinders,who said it was "more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the Earth".[54]The first time thatAustraliaappears to have been officially used was in April 1817, when GovernorLachlan Macquarieacknowledged the receipt of Flinders' charts of Australia fromLord Bathurst.[55]In December 1817, Macquarie recommended to theColonial Officethat it be formally adopted.[56]In 1824, theAdmiraltyagreed that the continent should be known officially by that name.[57]The first official published use of the new name came with the publication in 1830 ofThe Australia Directoryby theHydrographic Office.[58]

Colloquial names for Australia include "Oz","Straya "and"Down Under".[59]Other epithets include "the Great Southern Land", "the Lucky Country","the Sunburnt Country ", and" the Wide Brown Land ". The latter two both derive fromDorothea Mackellar's 1908 poem "My Country".[60]

History

Indigenous prehistory

Indigenous Australianscomprise two broad groups: theAboriginal peoplesof the Australian mainland (and surrounding islands including Tasmania), and theTorres Strait Islanders,who are a distinctMelanesianpeople. Human habitation of the Australian continent is estimated to have begun 50,000 to 65,000 years ago,[27][61][62][28]with the migration of people byland bridgesand short sea crossings from what is now Southeast Asia.[63]It is uncertain how many waves of immigration may have contributed to these ancestors of modern Aboriginal Australians.[64][65]TheMadjedbeberock shelter inArnhem Landis recognised as the oldest site showing the presence of humans in Australia.[66]The oldest human remains found are theLake Mungo remains,which have been dated to around 41,000 years ago.[67][68]

Aboriginal Australian culture is one of the oldest continuous cultures on Earth.[30][69][70][71]At the time of first European contact, Aboriginal Australians were complexhunter-gathererswith diverse economies and societies, and spread across at least250 different language groups.[72][73]Estimates of the Aboriginal population before British settlement range from 300,000 to one million.[74][75]Aboriginal Australians have an oral culture withspiritual valuesbased on reverence for the land and a belief in theDreamtime.[76]Certain groups engaged infire-stick farming,[77][78]fish farming,[79][80]and builtsemi-permanent shelters.[81][82]The extent to which some groups engaged in agriculture is controversial.[83][84][85]

The Torres Strait Islander people first settled their islands around 4,000 years ago.[86]Culturally and linguistically distinct from mainland Aboriginal peoples, they were seafarers and obtained their livelihood from seasonal horticulture and the resources of their reefs and seas.[87]Agriculture also developed on some islands and villages appeared by the 1300s.[88]

By the mid-18th century in northern Australia,contact, trade and cross-cultural engagementhad been established between local Aboriginal groups andMakassantrepangers,visiting from present-day Indonesia.[89][90][91]

European exploration and colonisation

The Dutch are the first Europeans that recorded sighting and making landfall on the Australian mainland.[92]The first ship and crew to chart the Australian coast and meet with Aboriginal people was theDuyfken,captained by Dutch navigatorWillem Janszoon.[93]He sighted the coast ofCape York Peninsulain early 1606, and made landfall on 26 February 1606 at thePennefather Rivernear the modern town ofWeipaon Cape York.[94]Later that year, Spanish explorerLuís Vaz de Torressailed through and navigated theTorres Strait Islands.[95]The Dutch charted the whole of the western and northern coastlines and named the island continent "New Holland"during the 17th century, and although no attempt at settlement was made,[94]a number of shipwrecksleft men either stranded or, as in the case of theBataviain 1629, marooned for mutiny and murder, thus becoming the first Europeans to permanently inhabit the continent.[96]In 1770, CaptainJames Cooksailed along and mapped the east coast, which he named "New South Wales"and claimed for Great Britain.[97]

Following the loss of itsAmerican coloniesin 1783, the British Government sent a fleet of ships, theFirst Fleet,under the command of CaptainArthur Phillip,to establish a newpenal colonyin New South Wales. A camp was set up and theUnion Flagraised atSydney Cove,Port Jackson,on 26 January 1788,[98][99]a date which later becameAustralia's national day.

Most early settlers wereconvicts,transportedfor petty crimes andassignedas labourers or servants to "free settlers" (willing immigrants). Onceemancipated,convicts tended to integrate into colonial society. Martial law was declared to suppress convict rebellions and uprisings,[100]and lasted for two years following the 1808Rum Rebellion,the only successful armed takeover of government in Australia.[101]Over the next two decades, social and economic reforms, together with the establishment of aLegislative CouncilandSupreme Court,saw New South Wales transition from a penal colony to a civil society.[102][103][104][page needed]

The indigenous population declined for 150 years following European settlement, mainly due to infectious disease.[105][106]British colonial authorities did not sign any treaties withAboriginal groups.[106][107]As settlement expanded, thousands of Indigenous people died infrontier conflictswhile others were dispossessed of their traditional lands.[108]

Colonial expansion

In 1803, a settlement was established inVan Diemen's Land(present-dayTasmania),[109]and in 1813,Gregory Blaxland,William LawsonandWilliam WentworthcrossedtheBlue Mountainswest of Sydney, opening the interior to European settlement.[110]The British claim extended to the whole Australian continent in 1827 when MajorEdmund Lockyerestablished a settlement onKing George Sound(modern-dayAlbany).[111]TheSwan River Colony(present-dayPerth) was established in 1829, evolving into the largest Australian colony by area,Western Australia.[112]In accordance with population growth, separate colonies were carved from New South Wales: Tasmania in 1825,South Australiain 1836,New Zealandin 1841,Victoriain 1851, andQueenslandin 1859.[113]South Australia was founded as a free colony—it never accepted transported convicts.[114]Growingopposition to the convict systemculminated in its abolition in the eastern colonies by the 1850s. Initially a free colony, Western Australia practised penal transportation from 1850 to 1868.[115]

The six colonies individually gainedresponsible governmentbetween 1855 and 1890, thus becoming elective democracies managing most of their own affairs while remaining part of theBritish Empire.[116]The Colonial Office in London retained control of some matters, notably foreign affairs.[117]

In the mid-19th century, explorers such asBurke and Willscharted Australia's interior.[118]Aseries of gold rushesbeginning in the early 1850s led to an influx of new migrants fromChina,North America and continental Europe,[119]as well as outbreaks ofbushrangingand civil unrest; the latter peaked in 1854 whenBallaratminers launched theEureka Rebellionagainst gold license fees.[120]The 1860s saw a surge inblackbirding,wherePacific Islanderswere forced into indentured labour, mainly in Queensland.[121][122]

From 1886, Australian colonial governments began introducing policies resulting in theremoval of many Aboriginal childrenfrom their families and communities.[123]TheSecond Boer War(1899–1902) marked the largest overseas deployment ofAustralia's colonial forces.[124][125]

Federation to the World Wars

On 1 January 1901,federation of the colonieswas achieved after a decade of planning,constitutional conventionsandreferendums,resulting in the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia as a nation under the newAustralian Constitution.[126]

After the1907 Imperial Conference,Australia and several other self-governing Britishsettler colonieswere given the status of self-governingdominionswithin the British Empire.[127]Australia was one of the founding members of theLeague of Nationsin 1920,[128]and subsequently of theUnited Nationsin 1945.[129]TheStatute of Westminster 1931formally ended the ability of the UK to pass laws with effect at the Commonwealth level in Australia without the country's consent. Australiaadopted itin 1942, but it was backdated to 1939 to confirm the validity of legislation passed by the Australian Parliament during World War II.[130][131][132]

TheAustralian Capital Territorywas formed in 1911 as the location for the future federal capital ofCanberra.[133]While it was being constructed,Melbourneserved as the temporary capital from 1901 to 1927.[134]TheNorthern Territorywas transferred from the control of the South Australian government to the federal parliament in 1911.[135]Australia became the colonial ruler of theTerritory of Papua(which had initially been annexed by Queensland in 1883) in 1902 and of theTerritory of New Guinea(formerlyGerman New Guinea) in 1920.[136][137]The two were unified as theTerritory of Papua and New Guineain 1949 and gained independence from Australia in 1975.[136][138]

In 1914, Australia joined theAlliesin fighting the First World War, and took part in many of the major battles fought on theWestern Front.[139]Of about 416,000 who served, about 60,000 were killed and another 152,000 were wounded.[140]Many Australians regard the defeat of theAustralian and New Zealand Army Corps(ANZAC) atGallipoliin 1915 as the "baptism of fire" that forged thenew nation's identity.[141][142][143]Thebeginning of the campaignis commemorated annually onAnzac Day,a date which rivalsAustralia Dayas the nation's most important.[144][145]

From 1939 to 1945, Australia joined theAlliesin fighting the Second World War. Australia'sarmed forcesfought in thePacific,EuropeanandMediterranean and Middle Easttheatres.[146][147]The shock of Britain'sdefeat in Singaporein 1942, followed soon after by thebombing of Darwinandother Japanese attacks on Australian soil,led to a widespread belief in Australia thata Japanese invasion was imminent,and a shift from the United Kingdom to theUnited Statesas Australia's principal ally and security partner.[148]Since 1951, Australia has been allied with the United States under theANZUStreaty.[149]

Post-war and contemporary eras

In the decades following World War II, Australia enjoyed significant increases in living standards, leisure time and suburban development.[150][151]Using the slogan "populate or perish", the nation encouraged alarge wave of immigration from across Europe,with such immigrants referred to as "New Australians".[152]

A member of theWestern Blocduring theCold War,Australia participated in theKorean Warand theMalayan Emergencyduring the 1950s and theVietnam Warfrom 1962 to 1972.[153]During this time, tensions over communist influence in society led tounsuccessful attemptsby theMenzies Governmentto ban theCommunist Party of Australia,[154]and abitter splitin theLabor Partyin 1955.[155]

As a result of a1967 referendum,the federal government gained the power to legislate with regard to Indigenous Australians, and Indigenous Australians were fully included in thecensus.[156]Pre-colonial land interests(referred to asnative titlein Australia) was recognised in law for the first time when theHigh Court of Australiaheld inMabo v Queensland (No 2)that Australia was neitherterra nullius( "land belonging to no one" ) or "desert and uncultivated land" at the time of European settlement.[157][158]

Following the abolition of the last vestiges of theWhite Australia policyin 1973,[159]Australia's demography and culture transformed as a result of a large and ongoing wave of non-European immigration, mostly from Asia.[160][161]The late 20th century also saw an increasing focus on foreign policy ties with otherPacific Rimnations.[162]TheAustralia Actssevered the remaining constitutional ties between Australia and the United Kingdom while maintaining the monarch in her independent capacity asQueen of Australia.[163][164]In a1999 constitutional referendum,55% of voters rejectedabolishing the monarchyand becoming a republic.[165]

Following theSeptember 11 attackson the United States, Australia joined the United States in fighting theAfghanistan Warfrom 2001 to 2021 and theIraq Warfrom 2003 to 2009.[166]The nation's trade relations also became increasingly oriented towards East Asia in the 21st century, with China becoming the nation'slargest trading partnerby a large margin.[167]

In 2020, during theCOVID-19 pandemic,several of Australia's largest cities werelocked downfor extended periods and free movement across the national and state borders was restricted in an attempt to slow the spread of theSARS-CoV-2 virus.[168]

Geography

General characteristics

Surrounded by the Indian and Pacific oceans,[N 7]Australia is separated from Asia by theArafuraandTimorseas, with theCoral Sealying off the Queensland coast, and theTasman Sealying between Australia and New Zealand. The world's smallest continent[170]andsixth largest country by total area,[171]Australia—owing to its size and isolation—is often dubbed the "island continent"[172]and is sometimes considered theworld's largest island.[173]Australia has 34,218 km (21,262 mi) of coastline (excluding all offshore islands),[174]and claims an extensiveExclusive Economic Zoneof 8,148,250 square kilometres (3,146,060 sq mi). This exclusive economic zone does not include theAustralian Antarctic Territory.[175]

Mainland Australia lies between latitudes9°and44° South,and longitudes112°and154° East.[176]Australia's size gives it a wide variety of landscapes, with tropical rainforests in the north-east, mountain ranges in the south-east, south-west and east, and desert in the centre.[177]The desert or semi-arid land commonly known as theoutbackmakes up by far the largest portion of land.[178]Australia is the driest inhabited continent; its annual rainfall averaged over continental area is less than 500 mm.[179]Thepopulation densityis 3.4 inhabitants per square kilometre, although the large majority of the population lives along the temperate south-eastern coastline. The population density exceeds 19,500 inhabitants per square kilometre in central Melbourne.[180]In 2021 Australia had 10% of the global permanent meadows and pastureland.[181]

TheGreat Barrier Reef,the world's largest coral reef,[182]lies a short distance off the north-east coast and extends for over 2,000 km (1,200 mi).Mount Augustus,claimed to be the world's largest monolith,[183]is located in Western Australia. At 2,228 m (7,310 ft),Mount Kosciuszkois the highest mountain on the Australian mainland. Even taller areMawson Peak(at 2,745 m (9,006 ft)), on the remote Australianexternal territoryofHeard Island,and, in the Australian Antarctic Territory,Mount McClintockandMount Menzies,at 3,492 m (11,457 ft) and 3,355 m (11,007 ft) respectively.[184]

Eastern Australia is marked by theGreat Dividing Range,which runs parallel to the coast of Queensland, New South Wales and much of Victoria. The name is not strictly accurate, because parts of the range consist of low hills, and the highlands are typically no more than 1,600 m (5,200 ft) in height.[185]Thecoastal uplandsand abelt of Brigalow grasslandslie between the coast and the mountains, while inland of the dividing range are large areas of grassland and shrubland.[185][186]These include thewestern plainsof New South Wales, and theMitchell Grass DownsandMulga Landsof inland Queensland.[187][188][189][190]The northernmost point of the mainland is the tropicalCape York Peninsula.[176]

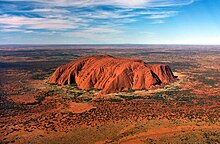

The landscapes of theTop Endand theGulf Country—with their tropical climate—include forest, woodland, wetland, grassland, rainforest and desert.[191][192][193]At the north-west corner of the continent are the sandstone cliffs and gorges ofThe Kimberley,and below that thePilbara.TheVictoria Plains tropical savannalies south of theKimberleyandArnhem Landsavannas, forming a transition between the coastal savannas and the interior deserts.[194][195][196]At the heart of the country are theuplands of central Australia.Prominent features of the centre and south includeUluru(also known as Ayers Rock), the famous sandstone monolith, and the inlandSimpson,Tirari and Sturt Stony,Gibson,Great Sandy, Tanami,andGreat Victoriadeserts, with the famousNullarbor Plainon the southern coast.[197][198][199][200]TheWestern Australian mulga shrublandslie between the interior deserts and Mediterranean-climateSouthwest Australia.[199][201]

Geology

Lying on theIndo-Australian Plate,the mainland of Australia is the lowest and most primordial landmass on Earth with a relatively stable geological history.[202][203]The landmass includes virtually all known rock types and from all geological time periods spanning over 3.8 billion years of the Earth's history. ThePilbara Cratonis one of only two pristineArchaean3.6–2.7 Ga (billion years ago) crusts identified on the Earth.[204]

Having been part of all majorsupercontinents,theAustralian continentbegan to form after the breakup ofGondwanain thePermian,with the separation of the continental landmass from the African continent and Indian subcontinent. It separated from Antarctica over a prolonged period beginning in thePermianand continuing through to theCretaceous.[205]When thelast glacial periodended in about 10,000 BC, rising sea levels formedBass Strait,separatingTasmaniafrom the mainland. Then between about 8,000 and 6,500 BC, the lowlands in the north were flooded by the sea, separating New Guinea, theAru Islands,and the mainland of Australia.[206]The Australian continent is moving towardEurasiaat the rate of 6 to 7 centimetres a year.[207]

The Australian mainland'scontinental crust,excluding the thinned margins, has an average thickness of 38km, with a range in thickness from 24 km to 59 km.[208]Australia's geology can be divided into several main sections, showcasing that the continent grew from west to east: the Archaeancratonicshields found mostly in the west,Proterozoicfold beltsin the centre andPhanerozoicsedimentary basins,metamorphic andigneous rocksin the east.[209]

The Australian mainland and Tasmania are situated in the middle of thetectonic plateand have no active volcanoes,[210]but due to passing over theEast Australia hotspot,recent volcanism has occurred during theHolocene,in theNewer Volcanics Provinceof western Victoria and south-eastern South Australia. Volcanism also occurs in the island of New Guinea (considered geologically as part of the Australian continent), and in the Australian external territory ofHeard Island and McDonald Islands.[211]Seismic activityin the Australian mainland and Tasmania is also low, with the greatest number of fatalities having occurred in the1989 Newcastle earthquake.[212]

Climate

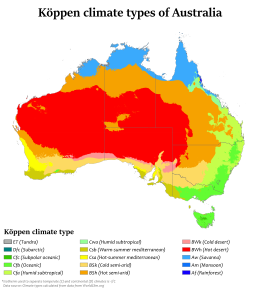

The climate of Australia is significantly influenced by ocean currents, including theIndian Ocean Dipoleand theEl Niño–Southern Oscillation,which is correlated with periodicdrought,and the seasonal tropical low-pressure system that produces cyclones in northern Australia.[214][215]These factors cause rainfall to vary markedly from year to year. Much of the northern part of the country has a tropical, predominantly summer-rainfall (monsoon).[179]The south-west corner of the country has aMediterranean climate.[216]The south-east ranges fromoceanic(Tasmania and coastal Victoria) tohumid subtropical(upper half of New South Wales), with the highlands featuringalpineandsubpolar oceanic climates.The interior isaridtosemi-arid.[179]

Driven by climate change, average temperatures have risenmore than 1°C since 1960.Associated changes in rainfall patterns and climate extremes exacerbate existing issues such as drought andbushfires.2019 was Australia's warmest recorded year,[217]and the2019–2020 bushfire seasonwas the country's worston record.[218]Australia's greenhouse gas emissionsper capita are among the highest in the world.[219]

Water restrictionsare frequently in place in many regions and cities of Australia in response to chronic shortages due to urban population increases and localised drought.[220][221]Throughout much of the continent,major floodingregularly follows extended periods of drought, flushing out inland river systems, overflowing dams and inundating large inland flood plains, as occurred throughout Eastern Australia in the early 2010s after the2000s Australian drought.[222]

Biodiversity

Although most of Australia is semi-arid or desert, the continent includes a diverse range of habitats fromalpineheaths totropical rainforests.Fungi typify that diversity—an estimated 250,000 species—of which only 5% have been described—occur in Australia.[223]Because of the continent's great age, extremely variable weather patterns, and long-term geographic isolation, much of Australia'sbiotais unique. About 85% of flowering plants, 84% of mammals, more than 45% ofbirds,and 89% of in-shore, temperate-zone fish areendemic.[224]Australia has at least 755 species of reptile, more than any other country in the world.[225]Besides Antarctica, Australia is the only continent that developed without feline species. Feral cats may have been introduced in the 17th century by Dutch shipwrecks, and later in the 18th century by European settlers. They are now considered a major factor in the decline and extinction of many vulnerable and endangered native species.[226]Seafaring immigrants from Asia are believed to have brought thedingoto Australia sometime after the end of the last ice age—perhaps 4000 years ago—and Aboriginal people helped disperse them across the continent as pets, contributing to the demise ofthylacineson the mainland.[227][page needed]Australia is also one of 17 megadiverse countries.[228]

Australian forestsare mostly made up of evergreen species, particularlyeucalyptustrees in the less arid regions;wattlesreplace them as the dominant species in drier regions and deserts.[229]Among well-knownAustralian animalsare themonotremes(theplatypusandechidna); a host ofmarsupials,including thekangaroo,koala, and wombat, and birds such as the emu and the kookaburra.[229]Australia is home tomany dangerous animalsincluding some of the most venomous snakes in the world.[230]Thedingowas introduced by Austronesian people who traded with Indigenous Australians around 3000BCE.[231]Many animal and plant species became extinct soon after first human settlement,[232]including theAustralian megafauna;others have disappeared since European settlement, among them the thylacine.[233][234]

Many of Australia's ecoregions, and the species within those regions, are threatened by human activities andintroducedanimal,chromistan,fungal and plant species.[235]All these factors have led to Australia's having the highest mammal extinction rate of any country in the world.[236]The federalEnvironment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999is the legal framework for the protection of threatened species.[237]Numerousprotected areashave been created under theNational Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversityto protect and preserve unique ecosystems;[238][239]65wetlandsarelistedunder theRamsar Convention,[240]and 16 naturalWorld Heritage Siteshave been established.[241]Australia was ranked 21st out of 178 countries in the world on the 2018Environmental Performance Index.[242]There are more than 1,800 animals and plants on Australia's threatened species list, including more than 500 animals.[243]

Paleontologistsdiscovered afossilsite of aprehistoricrainforestinMcGraths Flat,in South Australia, that presents evidence that this now ariddesertand dryshrubland/grasslandwas once home to an abundance of life.[244][245]

Government and politics

Australia is aconstitutional monarchy,aparliamentary democracyand afederation.[246]The country has maintained its mostly unchangedconstitutionalongside a stableliberal democraticpolitical system sinceFederationin 1901. It is one of the world's oldest federations, in which power is divided between the federal andstate and territorygovernments. TheAustralian system of governmentcombines elements derived from the political systems of the United Kingdom (afused executive,constitutional monarchy andstrong party discipline) and the United States (federalism,awritten constitutionandstrong bicameralismwith an elected upper house), resulting in a distinct hybrid.[247][248]

Government power is partially separatedbetween three branches:[249]

- Legislature: the bicameralParliament,comprising themonarch,theSenate,and theHouse of Representatives;

- Executive: theCabinet,led by the prime minister (the leader of the party or Coalition with a majority in the House of Representatives) and other ministers they have chosen. Formally appointed by the governor-general.[250]

- Judiciary: theHigh Courtand otherfederal courts

Charles IIIreigns asKing of Australiaand is represented in Australia by thegovernor-generalat the federal level and by thegovernorsat the state level, who bysection 63of the Constitution and convention act on the advice of their ministers.[251][252]Thus, in practice the governor-general acts as a legal figurehead for the actions of theprime ministerand the Cabinet. The governor-general may in some situations exercise powers in the absence or contrary to ministerial advice usingreserve powers.When these powers may be exercised is governed by convention and their precise scope is unclear. The most notable exercise of these powers was the dismissal of theWhitlam governmentin theconstitutional crisis of 1975.[253]

In the Senate (the upper house), there are 76 senators: twelve each from the states and two each from the mainland territories (the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory).[254]The House of Representatives (the lower house) has 151 members elected from single-memberelectoral divisions,commonly known as "electorates" or "seats", allocated to states on the basis of population, with each of the current states guaranteed a minimum of five seats.[255]The lower house has a maximum term of three years, but this is not fixed and governments usually dissolve the house early for an election at some point in the 6 months before the maximum.[256]Elections for both chambers are generally held simultaneously with senators having overlapping six-year terms except for those from the territories, whose terms are not fixed but are tied to the electoral cycle for the lower house. Thus only 40 of the 76 places in the Senate are put to each election unless the cycle is interrupted by adouble dissolution.[254]

Australia'selectoral systemusespreferential votingfor the House of Representatives and all state and territory lower house elections (with the exception of Tasmania and the ACT which use theHare-Clark system). The Senate and most state upper houses use the "proportional system"which combines preferential voting withproportional representationfor each state.Voting and enrolment is compulsoryfor all enrolled citizens 18 years and over in every jurisdiction.[257][258][259]The party with majority support in the House of Representatives forms the government and its leader becomes Prime Minister. In cases where no party has majority support, the governor-general has the constitutional power to appoint the prime minister and, if necessary, dismiss one that has lost the confidence of Parliament.[260]Due to the relatively unique position of Australia operating as aWestminsterparliamentary democracy with a powerful and elected upper house, the system has sometimes been referred to as having a "Washminster mutation",[261]or as asemi-parliamentary system.[262]

There are two major political groups that usually form government, federally and in the states: theAustralian Labor Partyand theCoalition,which is a formal grouping of theLiberal Partyand its minor partner, theNational Party.[263][264]TheLiberal National Partyand theCountry Liberal Partyare merged state branches in Queensland and the Northern Territory that function as separate parties at a federal level.[265]Within Australian political culture, the Coalition is consideredcentre-rightand the Labor Party is consideredcentre-left.[266]Independent members and several minor parties have achieved representation in Australian parliaments, mostly in upper houses. TheAustralian Greensare often considered the "third force" in politics, being the third largest party by both vote and membership.[267][268]

Themost recent federal electionwas held on 21 May 2022 and resulted in the Australian Labor Party, led byAnthony Albanese,being elected togovernment.[269]

States and territories

Australia has six states—New South Wales(NSW),Victoria(Vic),Queensland(Qld),Western Australia(WA),South Australia(SA) andTasmania(Tas)—and two mainland self-governing territories—theAustralian Capital Territory(ACT) and theNorthern Territory(NT).[270]

The states have the general power to make laws except in the few areas where the constitution grants the Commonwealth exclusive powers.[271][272]The Commonwealth can only make laws on topics listed in the constitution but its laws prevail over those of the states to the extent of any inconsistency.[273][274]Since Federation, the Commonwealth's power relative to the stateshas significantly increaseddue to the increasingly wide interpretation given to listed Commonwealth powers and because of the states'heavy financial relianceon Commonwealth grants.[275][276]

Each state and major mainland territory has its ownparliament—unicameralin the Northern Territory, the ACT and Queensland, and bicameral in the other states. The lower houses are known as theLegislative Assembly(theHouse of Assemblyin South Australia and Tasmania); the upper houses are known as theLegislative Council.Thehead of the governmentin each state is thePremierand in each territory theChief Minister.The King is represented in each state by agovernor.At the Commonwealth level, the King's representative is the governor-general.[277]

The Commonwealth government directly administers the internalJervis Bay Territoryand the other external territories: theAshmore and Cartier Islands,theCoral Sea Islands,theHeard Island and McDonald Islands,theIndian Ocean territories(Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands),Norfolk Island,[280]and theAustralian Antarctic Territory.[281][282][250]The remoteMacquarie IslandandLord Howe Islandare part of Tasmania and New South Wales respectively.[283][284]

Foreign relations

Australia is amiddle power,[43]whose foreign relations has three core bi-partisan pillars: commitment to the US alliance, engagement with theIndo-Pacificand support for international institutions, rules and co-operation.[285][286][287]Through theANZUSpact and its status as amajor non-NATO ally,Australia maintains aclose relationship with the US,which encompasses strong defence, security and trade ties.[288][289]In the Indo-Pacific, the country seeks to increase its trade ties through the open flow of trade and capital, whilst managing the rise of Chinese power by supporting the existing rules based order.[286]Regionally, the country is a member of thePacific Islands Forum,thePacific Community,theASEAN+6 mechanismand theEast Asia Summit.Internationally, the country is a member of theUnited Nations(of which it was a founding member), theCommonwealth of Nations,theOECDand theG20.This reflects the country's generally strong commitment tomultilateralism.[290][291]

Australia is a member of several defence, intelligence and security groupings including theFive Eyesintelligence alliance with the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand; the ANZUS alliance with the United States and New Zealand; theAUKUSsecurity treaty with the United States and United Kingdom; theQuadrilateral Security Dialoguewith the United States, India and Japan; theFive Power Defence Arrangementswith New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Malaysia and Singapore; and theReciprocal Accessdefence and security agreement with Japan.

Australia has pursued the cause of internationaltrade liberalisation.[292]It led the formation of theCairns GroupandAsia-Pacific Economic Cooperation,[293][294]and is a member of theOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD) and theWorld Trade Organization(WTO).[295][296]Beginning in the 2000s, Australia has entered into theComprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnershipand theRegional Comprehensive Economic Partnershipmultilateralfree trade agreementsas well as bilateral free trade agreements with theUnited States,China,Japan,South Korea,Indonesia,theUnited KingdomandNew Zealand,with the most recent deal with UK signed in 2023.[297]

Australia maintains a deeply integrated relationship with neighbouring New Zealand, with free mobility of citizens between the two countries under theTrans-Tasman Travel Arrangementand free trade under the Closer Economic Relations agreement.[298]The most favourably viewed countries by the Australian people in 2021 include New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Japan, Germany, Taiwan, Thailand, the United States and South Korea.[299]It also maintains aninternational aid programunder which some 75 countries receive assistance.[300]Australia ranked fourth in theCenter for Global Development's 2021Commitment to Development Index.[301]

The power over foreign policy is highly concentrated in the prime minister and thenational security committee,with major decision such as joining the2003 invasion of Iraqmade with without prior Cabinet approval.[302][303]Similarly, the Parliament does not play a formal role in foreign policy and the power to declare war lies solely with the executive government.[304]TheDepartment of Foreign Affairs and Tradesupports the executive in its policy decisions.

Military

The two main institutions involved in the management of Australia's armed forces are theAustralian Defence Force(ADF) and theDepartment of Defence,together known as "Defence".[305]The Australian Defence Force is the military wing, headed by thechief of the defence force,and contains three branches: theRoyal Australian Navy,theAustralian Armyand theRoyal Australian Air Force.In 2021, it had 84,865 currently serving personnel (including 60,286 regulars and 24,581 reservists).[306]The Department of Defence is the civilian wing and is headed by the secretary of defence. These two leaders collective manage Defence as adiarchy,with shared and joint responsibilities.[307]The titular role ofcommander-in-chiefis held by thegovernor-general,however actual command is vested in the chief of the Defence Force.[308]The executive branch of the Commonwealth government has overall control of the military through theminister of defence,who is subject to the decisions of Cabinet and itsNational Security Committee.[309]

In 2022, defence spending was 1.9% of GDP, representing the world's13th largest defence budget.[310]In 2024, the ADF had active operations in the Middle-East and the Indo-Pacific (including security and aid provisions), was contributing to UN forces in relation toSouth Sudan,Syria-IsraelandNorth Korea,and domestically wasassisting to prevent asylum-seekers enter the countryand withnatural disasterrelief.[311]

MajorAustralian intelligence agenciesinclude theAustralian Secret Intelligence Service(foreign intelligence), theAustralian Signals Directorate(signals intelligence) and theAustralian Security Intelligence Organisation(domestic security).

Human rights

Legal and social rights in Australia are regarded as among the most developed in the world.[39]Attitudes towards LGBT people are generally positive within Australia, andsame-sex marriagehas been legal in the nation since 2017.[312][313]Australia has had anti-discrimination laws regarding disability since 1992.[314]However, international organisations such asHuman Rights WatchandAmnesty Internationalhave expressed concerns in areas includingasylum-seeker policy,indigenous deaths in custody,the lack of entrenchedrights protectionandlaws restricting protesting.[315][316]

Economy

Australia'shigh-incomemixed-market economyis rich innatural resources.[317]It is the world'sfourteenth-largestby nominal terms, and the18th-largestbyPPP.As of 2021[update],it has thesecond-highest amountof wealth per adult, afterLuxembourg,[318]and has thethirteenth-highestfinancial assets per capita.[319]Australia has a labour force of some 13.5 million, with an unemployment rate of 3.5% as of June 2022.[320]According to theAustralian Council of Social Service,thepoverty rate of Australiaexceeds 13.6% of the population, encompassing 3.2 million. It also estimated that there were 774,000 (17.7%) children under the age of 15 living in relative poverty.[321][322]TheAustralian dollaris the national currency, which is also used by three island states in the Pacific:Kiribati,Nauru,andTuvalu.[323]

Australian government debt,about $963 billion in June 2022, exceeds 45.1% of the country's total GDP, and is the world'seighth-highest.[324]Australia had thesecond-highest levelofhousehold debtin the world in 2020, after Switzerland.[325]Its house pricesare among the highest in the world, especially in the large urban areas.[326]The large service sector accounts for about 71.2% of total GDP, followed by the industrial sector (25.3%), while theagriculture sectoris by far the smallest, making up only 3.6% of total GDP.[327]Australia is the world's21st-largest exporterand24th-largest importer.[328][329]China is Australia'slargest trading partnerby a wide margin, accounting for roughly 40% of the country's exports and 17.6% of its imports.[330]Other major export markets include Japan, the United States, and South Korea.[331]

Australia has high levels of competitiveness and economic freedom, and was ranked fifth in theHuman Development Indexin 2021.[332]As of 2022[update],it is ranked twelfth in theIndex of Economic Freedomand nineteenth in theGlobal Competitiveness Report.[333][334]It attracted 9.5 million international tourists in 2019,[335]and wasranked thirteenthamong the countries ofAsia-Pacificin 2019 for inbound tourism.[336]The 2021Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Reportranked Australia seventh-highest in the world out of 117 countries.[337]Its international tourism receipts in 2019 amounted to $45.7 billion.[336]

Energy

In 2021–22, Australia's generation of electricity was sourced fromblack coal(37.2%),brown coal(12%),natural gas(18.8%),hydro(6.5%),wind(11.1%),solar(13.3%),bio-energy(1.2%) and others (1.7%).[338][339]Total consumption of energy in this period was sourced from coal (28.4%), oil (37.3%), gas (27.4%) and renewables (7%).[340]From 2012 to 2022, the energy sourced from renewables has increased 5.7%, whilst energy sourced from coal has decreased 2.6%. The use of gas also increased by 1.5% and the use of oil stayed relatively stable with a reduction of only 0.2%.[341]

In 2020, Australia produced 27.7% of its electricity from renewable sources, exceeding thetargetset by the Commonwealth government in 2009 of 20% renewable energy by 2020.[342][343]A new target of 82% percent renewable energy by 2030 was set in 2022[344]and a target fornet zero emissionsby 2050 was set in 2021.[345]

Science and technology

In 2019, Australia spent $35.6 billion onresearch and development,allocating about 1.79% of GDP.[346]A recent study byAccenturefor the Tech Council shows that the Australian tech sector combined contributes $167 billion a year to the economy and employs 861,000 people.[347]In addition, recentstartup ecosystemsin Sydney and Melbourne are already valued at $34 billion combined.[348]Australia ranked 24th in theGlobal Innovation Index2023.[349]

With only 0.3% of the world's population, Australia contributed 4.1% of the world's published research in 2020, making it one of the top 10 research contributors in the world.[350][351]CSIRO,Australia's national science agency, contributes 10% of all research in the country, while the rest is carried out by universities.[351]Its most notable contributions include the invention ofatomic absorption spectroscopy,[352]the essential components ofWi-Fitechnology,[353]and the development of the first commercially successfulpolymer banknote.[354]

Australia is a key player in supportingspace exploration.Facilities such as theSquare Kilometre ArrayandAustralia Telescope Compact Arrayradio telescopes, telescopes such as theSiding Spring Observatory,and ground stations such as theCanberra Deep Space Communication Complexare of great assistance in deep space exploration missions, primarily byNASA.[355]

Demographics

Australia has an averagepopulation densityof 3.4 persons per square kilometre of total land area, which makes it one of themost sparsely populated countries in the world.The population is heavily concentrated on the east coast, and in particular in the south-eastern region betweenSouth East Queenslandto the north-east andAdelaideto the south-west.[356]

Australia is also highly urbanised, with 67% of the population living in the Greater Capital City Statistical Areas (metropolitan areas of the state and mainland territorial capital cities) in 2018.[357]Metropolitan areas with more than one million inhabitants areSydney,Melbourne,Brisbane,PerthandAdelaide.[358]

In common with many other developed countries, Australia is experiencing a demographic shift towards an older population, with more retirees and fewer people of working age. In 2021 theaverage ageof the population was 39 years.[359]In 2015, 2.15% of the Australian populationlived overseas,one of thelowest proportionsworldwide.[360]

| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sydney | NSW | 5,259,764 | 11 | Geelong | Vic | 289,400 | ||

| 2 | Melbourne | Vic | 4,976,157 | 12 | Hobart | Tas | 251,047 | ||

| 3 | Brisbane | Qld | 2,568,927 | 13 | Townsville | Qld | 181,665 | ||

| 4 | Perth | WA | 2,192,229 | 14 | Cairns | Qld | 155,638 | ||

| 5 | Adelaide | SA | 1,402,393 | 15 | Darwin | NT | 148,801 | ||

| 6 | Gold Coast–Tweed Heads | Qld/NSW | 706,673 | 16 | Toowoomba | Qld | 143,994 | ||

| 7 | Newcastle–Maitland | NSW | 509,894 | 17 | Ballarat | Vic | 111,702 | ||

| 8 | Canberra–Queanbeyan | ACT/NSW | 482,250 | 18 | Bendigo | Vic | 102,899 | ||

| 9 | Sunshine Coast | Qld | 355,631 | 19 | Albury-Wodonga | NSW/Vic | 97,676 | ||

| 10 | Wollongong | NSW | 305,880 | 20 | Launceston | Tas | 93,332 | ||

Ancestry and immigration

Between 1788 and theSecond World War,the vast majority ofsettlersandimmigrantscame from theBritish Isles(principallyEngland,IrelandandScotland), although there was significant immigration fromChinaandGermanyduring the 19th century. Following Federation in 1901, a strengthening of thewhite Australia policyrestricted further migration from these areas. However, in the decades immediately following the Second World War, Australia received alarge wave of immigrationfrom acrossEurope,with many more immigrants arriving fromSouthernandEastern Europethan in previous decades. All overt racial discrimination ended in 1973, withmulticulturalismbecoming official policy.[362]Subsequently, there has been a large and continuing wave of immigration from across the world, withAsiabeing the largest source of immigrants in the 21st century.[363]

Today, Australia has the world'seighth-largestimmigrant population, with immigrants accounting for 30% of the population, thehighest proportionamong majorWesternnations.[364][365]In 2022–23, 212,789 permanent migrants were admitted to Australia, with a net migration population gain of 518,000 people inclusive of non-permanent residents.[366][367]Most entered on skilled visas,[363]however the immigration program also offers visas for family members andrefugees.[368]

TheAustralian Bureau of Statisticsasks each Australian resident to nominate up to twoancestrieseachcensusand the responses are classified into broad ancestry groups.[369][370]At the 2021 census, the most commonly nominated ancestry groups as a proportion of the total population were:[371]57.2%European(including 46%North-West Europeanand 11.2%SouthernandEastern European), 33.8%Oceanian,[N 8]17.4%Asian(including 6.5%SouthernandCentral Asian,6.4%North-East Asian,and 4.5%South-East Asian), 3.2%North African and Middle Eastern,1.4%Peoples of the Americas,and 1.3%Sub-Saharan African.At the 2021 census, the most commonly nominated individual ancestries as a proportion of the total population were:[N 9][4]

At the 2021 census, 3.8% of the Australian population identified as beingIndigenous—Aboriginal AustraliansandTorres Strait Islanders.[N 12][374]

Language

Although English is not the official language of Australia in law, it is thede factoofficial and national language.[375][376]Australian Englishis a major variety of the language with a distinctive accent and lexicon,[377]and differs slightly from other varieties of English in grammar and spelling.[378]General Australianserves as the standard dialect.[379]

At the 2021 census, English was the only language spoken in the home for 72% of the population. The next most common languages spoken at home wereMandarin(2.7%),Arabic(1.4%),Vietnamese(1.3%),Cantonese(1.2%) andPunjabi(0.9%).[380]

Over 250Australian Aboriginal languagesare thought to have existed at the time of first European contact.[381]The National Indigenous Languages Survey (NILS) for 2018–19 found that more than 120 Indigenous language varieties were in use or being revived, although 70 of those in use were endangered.[382]The 2021 census found that 167 Indigenous languages were spoken at home by 76,978 Indigenous Australians — Yumplatok (Torres Strait Creole),Djambarrpuyngu(aYolŋu language) andPitjantjatjara(aWestern Desert language) were among the most widely spoken.[383]NILS and the Australian Bureau of Statistics use different classifications for Indigenous Australian languages.[384]

The Australian sign language known asAuslanwas used at home by 16,242 people at the time of the 2021 census.[385]

Religion

Australia has nostate religion;section 116 of theAustralian Constitutionprohibits theAustralian governmentfrom making any law to establish any religion, impose any religious observance, or prohibit the free exercise of any religion.[386]However, the states still retain the power to pass religiously discriminatory laws.[387]

At the 2021 census, 38.9% of the population identified as having"no religion",[4]up from 15.5% in 2001.[388]The largest religion isChristianity(43.9% of the population).[4]The largest Christian denominations are theRoman Catholic Church(20% of the population) and theAnglican Church of Australia(9.8%). Non-British immigration since theSecond World Warhas led to the growth of non-Christian religions, the largest of which areIslam(3.2%),Hinduism(2.7%),Buddhism(2.4%),Sikhism(0.8%), andJudaism(0.4%).[389][4]

In 2021, just under 8,000 people declared an affiliation with traditional Aboriginal religions.[4]InAustralian Aboriginal mythologyand theanimistframework developed in Aboriginal Australia, theDreamingis asacredera in which ancestraltotemicspirit beings formedThe Creation.The Dreaming established the laws and structures of society and the ceremonies performed to ensure continuity of life and land.[390]

Health

Australia's life expectancy of 83 years (81 years for males and 85 years for females),[391]is thefifth-highest in the world.It has the highest rate of skin cancer in the world,[392]whilecigarette smokingis the largest preventable cause of death and disease, responsible for 7.8% of the total mortality and disease. Ranked second in preventable causes ishypertensionat 7.6%, with obesity third at 7.5%.[393][394]Australia ranked 35th in the world in 2012 for its proportion of obese women[395]and near the top ofdeveloped nationsfor its proportion ofobeseadults;[396]63% of its adult population is either overweight or obese.[397]

Australia spent around 9.91% of its total GDP to health care in 2021.[398]It introduced anational insurance schemein 1975.[399]Following a period in which access to the scheme was restricted, the scheme becameuniversalonce more in 1981 under the name ofMedicare.[400]The program is nominally funded by an income tax surcharge known as theMedicare levy,currently at 2%.[401]The states manage hospitals and attached outpatient services, while the Commonwealth funds thePharmaceutical Benefits Scheme(subsidising the costs of medicines) andgeneral practice.[399]

Education

School attendance, or registration forhome schooling,[402]is compulsory throughout Australia. Education is primarily the responsibility of the individual states and territories, however the Commonwealth has significant influence through funding agreements.[403]Since 2014, anational curriculumdeveloped by the Commonwealth has been implemented by the states and territories.[404]Attendance rules vary between states, but in general children are required to attend school from the age of about 5 until about 16.[405][406]In some states (Western Australia, Northern Territory and New South Wales), children aged 16–17 are required to either attend school or participate in vocational training, such as anapprenticeship.[407][408][409][410]

Australia has an adult literacy rate that was estimated to be 99% in 2003.[411]However, a 2011–2012 report for the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that 44% of the population does not have high literary and numeracy competence levels, interpreted by others as suggesting that they do not have the "skills needed for everyday life".[412][413][414]

Australia has 37 government-funded universities and three private universities, as well as a number of other specialist institutions that provide approved courses at the higher education level.[415]The OECD places Australia among the most expensive nations to attend university.[416]There is a state-based system of vocational training, known asTAFE,and many trades conduct apprenticeships for training new tradespeople.[417]About 58% of Australians aged from 25 to 64 have vocational or tertiary qualifications[418]and the tertiary graduation rate of 49% is the highest among OECD countries. 30.9% of Australia's population has attained a higher education qualification, which is among the highest percentages in the world.[419][420][421]

Australia has the highest ratio ofinternational studentsper head of population in the world by a large margin, with 812,000 international students enrolled in the nation's universities and vocational institutions in 2019.[422][423]Accordingly, in 2019, international students represented on average 26.7% of the student bodies of Australian universities. International education therefore represents one of the country's largest exports and has a pronounced influence on the country's demographics, with a significant proportion of international students remaining in Australia after graduation on various skill and employment visas.[424]Education is Australia's third-largest export, after iron ore and coal, and contributed over $28 billion to the economy in 2016–17.[351]

Culture

Contemporary Australian culture reflects the country'sIndigenous traditions,Anglo-Celticheritage, and post 1970s history ofmulticultural immigration.[426][427][428]Theculture of the United Stateshas also been influential.[429]The evolution of Australian culture since British colonisation has given rise to distinctive cultural traits.[430][431]

Many Australians identify egalitarianism,mateship,irreverence and a lack of formality as part of their national identity.[432][433][434]These find expression inAustralian slang,as well asAustralian humour,which is often characterised as dry, irreverent and ironic.[435][436]New citizens and visa holders are required to commit to "Australian values", which are identified by theDepartment of Home Affairsas including: a respect for the freedom of the individual; recognition of the rule of law; opposition to racial, gender and religious discrimination; and an understanding of the "fair go",which is said to encompass the equality of opportunity for all and compassion for those in need.[437]What these values mean, and whether or not Australians uphold them, has been debated since before Federation.[438][439][440][441]

Arts

Australia has over 100,000Aboriginal rock artsites,[443]and traditional designs, patterns and stories infusecontemporary Indigenous Australian art,"the last great art movement of the 20th century" according to criticRobert Hughes;[444]its exponents includeEmily Kame Kngwarreye.[445]Early colonial artists showed a fascination with the unfamiliar land.[446]Theimpressionisticworks ofArthur Streeton,Tom Robertsand other members of the 19th-centuryHeidelberg School—the first "distinctively Australian" movement in Western art—gave expression to nationalist sentiments in the lead-up to Federation.[446]While the school remained influential into the 1900s,modernistssuch asMargaret PrestonandClarice Beckett,and, later,Sidney Nolan,explored new artistic trends.[446]The landscape remained central to the work of Aboriginal watercolouristAlbert Namatjira,[447]as well asFred Williams,Brett Whiteleyand other post-war artists whose works, eclectic in style yet uniquely Australian, moved between thefigurativeand theabstract.[446][448]

Australian literaturegrew slowly in the decades following European settlement though Indigenousoral traditions,many of which have since been recorded in writing, are much older.[449]In the 19th century,Henry LawsonandBanjo Patersoncaptured the experience ofthe bushusing a distinctive Australian vocabulary.[450]Their works are still popular; Paterson'sbush poem"Waltzing Matilda"(1895) is regarded as Australia's unofficial national anthem.[451]Miles Franklinis the namesake of Australia'smost prestigious literary prize,awarded annually to the best novel about Australian life.[452]Its first recipient,Patrick White,went on to win theNobel Prize in Literaturein 1973.[453]AustralianBooker Prizewinners includePeter Carey,Thomas KeneallyandRichard Flanagan.[454]Australian public intellectuals have also written seminal works in their respective fields, including feministGermaine Greerand philosopherPeter Singer.[455]

In the performing arts, Aboriginal peoples have traditions of religious and secular song, dance and rhythmic music often performed incorroborees.[456]At the beginning of the 20th century,Nellie Melbawas one of the world's leading opera singers,[457]and later popular music acts such as theBee Gees,AC/DC,INXSandKylie Minogueachieved international recognition.[458]Many of Australia's performing arts companies receive funding through the Australian government'sAustralia Council.[459]There is a symphony orchestra in each state,[460]and a national opera company,Opera Australia,[461]well known for its famoussopranoJoan Sutherland.[462]Ballet and dance are represented byThe Australian Balletand various state companies. Each state has a publicly funded theatre company.[463]

Media

The Story of the Kelly Gang(1906), the world's firstfeature-lengthnarrative film, spurred a boom inAustralian cinemaduring thesilent filmera.[464]After World War I,Hollywoodmonopolised the industry,[465]and by the 1960s Australian film production had effectively ceased.[466]With the benefit of government support, theAustralian New Waveof the 1970s brought provocative and successful films, many exploring themes of national identity, such asPicnic at Hanging Rock,Wake in FrightandGallipoli,[467]whileCrocodile Dundeeand theOzploitationmovement'sMad Maxseries became international blockbusters.[468]In a film market flooded with foreign content, Australian films delivered a 7.7% share of the local box office in 2015.[469]TheAACTAsare Australia's premier film and television awards, and notableAcademy Award winners from AustraliaincludeGeoffrey Rush,Nicole Kidman,Cate BlanchettandHeath Ledger.[470]

Australia has two public broadcasters (theAustralian Broadcasting Corporationand the multiculturalSpecial Broadcasting Service), three commercial television networks, several pay-TV services,[471]and numerous public, non-profit television and radio stations. Each major city has at least one daily newspaper,[471]and there are two national daily newspapers,The AustralianandThe Australian Financial Review.[471]In 2020,Reporters Without Bordersplaced Australia 25th on a list of 180 countries ranked bypress freedom,behind New Zealand (8th) but ahead of the United Kingdom (33rd) and United States (44th).[472]This relatively low ranking is primarily because of the limited diversity of commercial media ownership in Australia;[473]most print media are under the control ofNews Corporation(59%) andNine Entertainment Co(23%).[474]

Cuisine

Most Indigenous Australian groups subsisted on ahunter-gathererdiet of native fauna and flora, otherwise calledbush tucker.[475]It has increased in popularity among non-Indigenous Australians since the 1970s, with examples such aslemon myrtle,themacadamia nutandkangaroo meatnow widely available.[476][477]

The first colonists introducedBritishandIrish cuisineto the continent.[478][479]This influence is seen in dishes such asfish and chips,and in theAustralian meat pie,which is related to the Britishsteak pie.Also during the colonial period, Chinese migrants paved the way for a distinctiveAustralian Chinese cuisine.[480]

Post-war migrants transformed Australian cuisine, bringing with them their culinary traditions and contributing to newfusiondishes.[481]Italians introduced espresso coffee and, along with Greeks, helped develop Australia's café culture, of which theflat whiteand "smashed avo"on toast are now considered Australian staples.[482][483]Pavlovas,lamingtons,VegemiteandAnzac biscuitsare also often called iconic Australian foods.[484]

Australia is a leading exporter and consumer ofwine.[485]Australian wineis produced mainly in the southern, cooler parts of the country.[486]The nation also ranks highly inbeer consumption,[487]with each state and territory hosting numerous breweries.

Sport and recreation

The most popular sports in Australia by adult participation are: swimming, athletics, cycling, soccer, golf, tennis, basketball, surfing, netball and cricket.[489]

Australia is one of five nations to have participated in everySummer Olympicsof the modern era,[490]and has hosted the Games twice:1956in Melbourne and2000in Sydney.[491]It is also set to host the2032 GamesinBrisbane.[492]Australia has also participated in everyCommonwealth Games,[493]hosting the event in1938,1962,1982,2006and2018.[494]

Cricket is a major national sport.[495]TheAustralian national cricket teamcompeted againstEnglandin the firstTestmatch (1877) and the firstOne Day International(1971), and againstNew Zealandin the firstTwenty20 International(2004), winning all three games.[496]It has also won the men'sCricket World Cupa record six times.[497]

Australia has professional leagues forfour football codes,whose relative popularity isdivided geographically.[498]Originating in Melbourne in the 1850s,Australian rules footballattracts the most television viewers in all states except New South Wales and Queensland, whererugby leagueholds sway, followed byrugby union.[499]Soccer,while ranked fourth in television viewers and resources, has the highest overall participation rates.[500]

Thesurf lifesavingmovement originated in Australia, and the volunteer lifesaver is one of the country's icons.[501]

See also

Notes

- ^Australia also has aroyal anthem,"God Save the King",which may be played in place of or alongside the national anthem when members of theroyal familyare present. If not played alongside the royal anthem, the national anthem is instead played at the end of an official event.[1]

- ^Sydney is the largest city based on Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Greater Capital City Statistical Areas (GCCSAs). These represent labour markets and the functional area of Australian capital cities.[2]Melbourne is larger based on ABS Significant Urban Areas (SUAs). These represent Urban Centres, or groups of contiguous Urban Centres, that contain a population of 10,000 people or more.[3]

- ^The religion question is optional in the Australian census.

- ^abThere are minor variations from three basic time zones; seeTime in Australia.

- ^The earliest recorded use of the wordAustraliain English was in 1625 in "A note of Australia del Espíritu Santo, written by SirRichard Hakluyt",published bySamuel PurchasinHakluytus Posthumus,a corruption of the original Spanish name "Austrialia del Espíritu Santo" (Southern Land of the Holy Spirit)[49][50][51]for an island inVanuatu.[52]The Dutch adjectival formaustralischewas used in a Dutch book inBatavia(Jakarta) in 1638, to refer to the newly discovered lands to the south.[53]

- ^For instance, the 1814 workA Voyage to Terra Australis

- ^Australia describes the body of water south of its mainland as theSouthern Ocean,rather than the Indian Ocean as defined by theInternational Hydrographic Organization(IHO). In 2000, a vote of IHO member nations defined the term "Southern Ocean" as applying only to the waters betweenAntarcticaand60° southlatitude.[169]

- ^Includes those who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry.[4]The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry have at least partialAnglo-CelticEuropeanancestry.[372]

- ^Each person may nominate more than one ancestry, so total may exceed 100%.[373]

- ^The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry have at least partialAnglo-CelticEuropeanancestry.[372]

- ^Those who nominated their ancestry as "Australian Aboriginal". Does not includeTorres Strait Islanders.This relates to nomination of ancestry and is distinct from persons who identify as Indigenous (Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander) which is a separate question.

- ^Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

- ^The area of the Australia with outlying islands. Mainland Australia (including Tasmania) is 7,688,287 square kilometres

References

- ^"Australian National Anthem".Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2023.Retrieved9 January2024.

- ^"Regional population".Australian Bureau of Statistics. 20 April 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2023.Retrieved27 May2023.

- ^Turnbull, Tiffanie (17 April 2023)."Melbourne overtakes Sydney as Australia's biggest city".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2023.Retrieved27 May2023.

- ^abcdefg"General Community Profile"(Excelfile). 2021 Census of Population and Housing. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- ^Pronounced "Ozzy"

- ^"Aussie".Macquarie Dictionary.16 October 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2024.Retrieved8 February2024.

- ^Collins English Dictionary.Bishopbriggs, Glasgow:HarperCollins.2009. p. 18.ISBN978-0-0078-6171-2.

- ^"Australia".Central Intelligence Agency. 24 December 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 9 January 2021.Retrieved10 June2024– via CIA.gov.

- ^"Area of Australia - States and Territories".Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2024.Retrieved18 February2024.

- ^"Area of Australia - States and Territories".Geoscience Australia.Australian Government. 26 July 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2024.

- ^"Surface water and surface water change".Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD).Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2021.Retrieved11 October2020.

- ^"Surface water and surface water change".Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD).Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2021.Retrieved11 October2020.

- ^ab"Population clock and pyramid".Australian Bureau of Statisticswebsite.Commonwealth of Australia. 5 March 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 8 February 2024.Retrieved5 March2024.The population estimate shown is automatically calculated daily at 00:00 UTC and is based on data obtained from the population clock on the date shown in the citation.

- ^"National, state and territory population".Australian Bureau of Statistics. 26 September 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 21 November 2022.Retrieved26 September2022.

- ^abcd"World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Australia)".www.imf.org.International Monetary Fund.16 April 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2024.Retrieved16 April2024.

- ^"Australia Gini Coefficient, 1995 – 2023 | CEIC Data".www.ceicdata.com.Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2024.Retrieved4 March2024.

- ^"Human Development Report 2023/24"(PDF).United Nations Development Programme.13 March 2024.Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 March 2024.Retrieved13 March2024.

- ^Australian Government (March 2023)."Dates and time".Style Manual.Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2023.Retrieved6 May2023.

- ^Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act(Imp) 63 & 64 Vict, c 12,s 3Archived9 January 2024 at theWayback Machine

- ^41% of the Antarctic continent is also claimed by the country,however this is only recognised by the UK, France, New Zealand and Norway.

- ^Korsch RJ.; et al. (2011). "Australian island arcs through time: Geodynamic implications for the Archean and Proterozoic".Gondwana Research.19(3): 716–734.Bibcode:2011GondR..19..716K.doi:10.1016/j.gr.2010.11.018.

- ^Macey, Richard (21 January 2005)."Map from above shows Australia is a very flat place".The Sydney Morning Herald.ISSN0312-6315.OCLC226369741.Archivedfrom the original on 10 October 2017.Retrieved5 April2010.

- ^"The Australian continent".australia.gov.au.Archived fromthe originalon 13 March 2020.Retrieved13 August2018.

- ^"Deserts".Geoscience Australia.Australian Government. 15 May 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 5 June 2014.Retrieved13 August2018.

- ^Kelly, Karina (13 September 1995)."A Chat with Tim Flannery on Population Control".Australian Broadcasting Corporation.Archived fromthe originalon 13 January 2010.Retrieved23 April2010."Well, Australia has by far the world's least fertile soils".

- ^Grant, Cameron (August 2007)."Damaged Dirt"(PDF).The Advertiser.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 July 2011.Retrieved23 April2010.

Australia has the oldest, most highly weathered soils on the planet.

- ^abClarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley; Smith, Mike; Roberts, Richard G.; Hayes, Elspeth; Lowe, Kelsey; Carah, Xavier; Florin, S. Anna; McNeil, Jessica; Cox, Delyth; Arnold, Lee J.; Hua, Quan; Huntley, Jillian; Brand, Helen E. A.; Manne, Tiina; Fairbairn, Andrew; Shulmeister, James; Lyle, Lindsey; Salinas, Makiah; Page, Mara; Connell, Kate; Park, Gayoung; Norman, Kasih; Murphy, Tessa; Pardoe, Colin (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago".Nature.547(7663): 306–310.Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C.doi:10.1038/nature22968.hdl:2440/107043.ISSN0028-0836.PMID28726833.S2CID205257212.

- ^abVeth, Peter; O'Connor, Sue (2013). "The past 50,000 years: an archaeological view". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.).The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19.ISBN978-1-1070-1153-3.

- ^Williams, Martin A. J.; Spooner, Nigel A.; McDonnell, Kathryn; O'Connell, James F. (January 2021)."Identifying disturbance in archaeological sites in tropical northern Australia: Implications for previously proposed 65,000-year continental occupation date".Geoarchaeology.36(1): 92–108.Bibcode:2021Gearc..36...92W.doi:10.1002/gea.21822.ISSN0883-6353.S2CID225321249.Archivedfrom the original on 4 October 2023.Retrieved16 October2023.

- ^abFlood, J.(2019).The Original Australians: The story of the Aboriginal People(2nd ed.). Crows Nest NSW: Allen & Unwin. p. 161.ISBN978-1-76087-142-0.

- ^abContiades, X.; Fotiadou, A. (2020).Routledge Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Change.Taylor & Francis. p. 389.ISBN978-1-3510-2097-8.Archivedfrom the original on 19 April 2023.Retrieved17 July2023.

- ^"Geographic Distribution of the Population".24 May 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2021.Retrieved1 December2012.

- ^"Regional population".Australian Bureau of Statistics.20 April 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 10 October 2023.Retrieved23 April2023.

- ^"The Success of Australia's Multiculturalism".Australian Human Rights Commission.9 March 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2024.Retrieved4 February2024.

[In Australia], multiculturalism as policy emerged in the 1970s. It replaced the initial policy approach of assimilation that was adopted towards mass immigration from Europe in the immediate post-Second World War years. In the very simplest of terms, multiculturalism means there is public endorsement and recognition of cultural diversity. It means a national community defines its national identity not in ethnic or racial terms, but in terms that can include immigrants. It means a national community accepts that its common identity may evolve to reflect its composition.

- ^"Culturally and linguistically Diverse Australian".Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.2024.Archivedfrom the original on 19 February 2024.Retrieved20 February2024.

- ^O'Donnell, James (27 November 2023)."Is Australia a cohesive nation?".ABC Australia.Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2024.Retrieved21 February2024.

- ^"Trade and Investment at a glance 2021".Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.Australian Government. 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2023.Retrieved27 February2024.

- ^"Australian Industry".Australian Bureau of Statistics.Australian Government. 26 May 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2024.Retrieved27 February2024.

- ^ab"Statistics and rankings".Global Australia.18 May 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 28 March 2023.Retrieved28 March2023.

- ^"World Economic Outlook Database, April 2015".International Monetary Fund.6 September 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 6 September 2015.Retrieved1 April2019.

- ^"Human Development Report 2021-22"(PDF).United Nations Development Programme.2022.Archived(PDF)from the original on 8 September 2022.Retrieved9 September2022.

- ^"Australians the world's wealthiest".The Sydney Morning Herald.31 October 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 10 July 2014.Retrieved24 July2012.

- ^abLowy Institute Asian Power Index(PDF)(Report). 2023. p. 29.ISBN978-0-6480189-3-3.Archived(PDF)from the original on 20 February 2024.Retrieved4 February2024.

- ^"Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2017"(PDF).www.sipri.org.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 May 2018.Retrieved12 August2018.

- ^Rachman, Gideon (13 March 2023)."Aukus, the Anglosphere and the return of great power rivalry".Financial Times.Archivedfrom the original on 20 March 2023.Retrieved19 March2023.

- ^Australian pronunciations:Macquarie Dictionary,Fourth Edition(2005) Melbourne, The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd.ISBN978-1-876429-14-0

- ^"australia | Etymology, origin and meaning of the name australia by etymonline".www.etymonline.com.Archivedfrom the original on 29 January 2022.Retrieved15 January2022.

- ^Clarke, Jacqueline; Clarke, Philip (10 August 2014)."Putting 'Australia' on the map".The Conversation.Archivedfrom the original on 2 March 2022.Retrieved15 January2022.

- ^"He named it Austrialia del Espiritu Santo and claimed it for Spain"Archived17 August 2013 at theWayback MachineThe Spanish quest for Terra Australis|State Library of New South Wales Page 1

- ^"A note on 'Austrialia' or 'Australia' Rupert Gerritsen – Journal of The Australian and New Zealand Map Society Inc. The Globe Number 72, 2013Archived12 June 2016 at theWayback MachinePosesion en nombre de Su Magestad (Archivo del Museo Naval, Madrid, MS 951) p. 3.

- ^"The Illustrated Sydney News".Illustrated Sydney News.National Library of Australia. 26 January 1888. p. 2.Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2023.Retrieved29 January2012.

- ^Purchas, vol. iv, pp. 1422–1432, 1625

- ^Scott, Ernest (2004) [1914].The Life of Captain Matthew Flinders.Kessinger Publishing. p. 299.ISBN978-1-4191-6948-9.Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2024.Retrieved17 July2023.

- ^Flinders, Matthew (1814)A Voyage to Terra AustralisG. and W. Nicol

- ^"Who Named Australia?".The Mail (Adelaide, South Australia).Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 11 February 1928. p. 16.Archivedfrom the original on 17 April 2021.Retrieved14 February2012.

- ^Weekend Australian, 30–31 December 2000, p. 16

- ^Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2007).Life in Australia(PDF).Commonwealth of Australia. p. 11.ISBN978-1-9214-4630-6.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 17 October 2009.Retrieved30 March2010.