Congenital syphilis

| Congenital syphilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Notchedincisorsknown asHutchinson's teethwhich are characteristic of congenital syphilis | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Rash,fever,large liver and spleen,skeletal abnormalities[1] |

| Usual onset | Unborn baby, newborn baby or later[1] |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | Early & late[2] |

| Causes | Treponema pallidum[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Signs, symptoms, blood tests, CSF tests |

| Prevention | Adequate screening and treatment in pregnant mother[2] |

| Treatment | Antibiotic[3] |

| Medication | Penicillinby injection;Procaine benzylpenicillin,benzylpenicillin,benzathine penicillin G[3] |

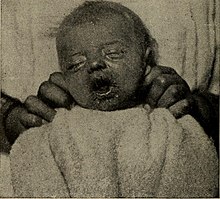

Congenital syphilisissyphilisthat occurs when a mother with untreated syphilis passes the infection to her baby duringpregnancyor atbirth.[4]It may present in thefetus,infant,or later.[1][5]Clinical features vary and differ between early onset, that is presentation before 2-years of age, and late onset, presentation after age 2-years.[4]Infection in theunborn babymay present aspoor growth,non-immune hydropsleading topremature birthorloss of the baby,orno signs.[2][4]Affected newborns mostly initially have no clinical signs.[4]They may besmalland irritable.[4]Characteristic features include a rash,fever,large liver and spleen,arunny and congested nose,andinflammation around boneorcartilage.[2][4]There may bejaundice,large glands,pneumonia(pneumonia alba),meningitis,warty bumps on genitals,deafness or blindness.[4][6][7]Untreated babies that survive the early phase may develop skeletal deformities including deformity of thenose,lower legs,forehead,collar bone,jaw,andcheek bone.[4]There may be a perforated or high archedpalate,and recurrentjoint disease.[2][4]Other late signs includelinear perioral tears,intellectual disability,hydrocephalus,and juvenile general paresis.[4]Seizuresandcranial nerve palsiesmay first occur in both early and late phases.[4]Eighth nerve palsy,interstitial keratitisandsmall notched teethmay appear individually or together; known asHutchinson's triad.[4]

It is caused by thebacteriumTreponema pallidumsubspeciespallidumwhen it infects the baby after crossing the placenta or from contact with a syphilitic sore at birth.[4][5]It is not transmitted duringbreastfeedingunless there is anopen soreon the mother'sbreast.[4]Theunborn babycan become infected at any time during the pregnancy.[4]Most cases occur due to inadequate antenatal screening and treatment during pregnancy.[8]The baby is highly infectious if the rash and snuffles are present.[4]The disease may be suspected from tests on the mother; blood tests andultrasound.[9]Tests on the baby may include blood tests,CSFanalysis andmedical imaging.[10]Findings may revealanemiaandlow platelets.[4]Other findings may includelow sugars,proteinuriaandhypopituitarism.[4]Theplacentamay appear large and pale.[4]Other investigations include testing forHIV.[10]

Prevention is bysafe sexto prevent syphilis in the mother, and early screening and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy.[6]One intramuscular injection ofbenzathine penicillin Gadministered to a pregnant woman early in the illness can prevent congenital syphilis in her baby.[11]Treatment of suspected congenital syphilis is withpenicillinby injection;benzylpenicillininto vein,orprocaine benzylpenicillininto muscle.[3][10]During times of penicillin unavailability,ceftriaxonemay be an alternative.[10]Where there ispenicillin allergy,antimicrobial desensitisation is an option.[10][12]

Syphilis affects around one million pregnancies a year.[13]In 2016, there were around 473 cases of congenital syphilis per 100,000 live births and 204,000 deaths from the disease worldwide.[14]Of the 660,000 congenital syphilis cases reported in 2016, 143,000 resulted in deaths of unborn babies, 61,000 deaths of newborn babies, 41,000 low birth weights or preterm births, and 109,000young childrendiagnosed with congenital syphilis.[15]Around 75% were from the WHO's African and Eastern Mediterranean regions.[2]Serological tests for syphilis were introduced in 1906, and it was later shown that transmission occurred from the mother.[16]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Untreated early syphilis infections results in a high risk of poor pregnancy outcomes, includingsaddle nose,lower extremity abnormalities,miscarriages,premature births,stillbirths,or death innewborns.Some infants with congenital syphilis have symptoms at birth, but many develop symptoms later. Symptoms may include rash, fever,large liver and spleen,and skeletal abnormalities.[17]Newborns will typically not develop a primary syphilitic chancre but may present with signs of secondary syphilis (i.e. generalized body rash). Often these babies will develop syphiliticrhinitis( "snuffles" ), the mucus from which is laden with theT. pallidumbacterium, and therefore highly infectious. If a baby with congenital syphilis is not treated early, damage to the bones, teeth, eyes, ears, and brain can occur.[17]

Neurosyphilis in newborns may present ascranial nerve palsies,cerebral infarcts (strokes),seizuresor eye abnormalities.[18]

Many newborns with congenital syphilis, 55% by some estimates, do not exhibit any symptoms initially, with signs and symptoms developing days to months later.[18]

Early

[edit]

This is a subset of cases of congenital syphilis. Newborns may be asymptomatic and are only identified on routineprenatal screening.If not identified and treated, these newborns develop poor feeding andrunny nose.[17]By definition, early congenital syphilis occurs in children between 0 and 2 years old.[19]

Late

[edit]

Congenital syphilis that is diagnosed after 2 years of age, either because it was not diagnosed earlier or because it was incompletely treated, is classified as late congenital syphilis.[19]The signs of late congenital syphilis tend to reflect early damage to developing tissues that does not become apparent until years later,[20]such asHutchinson's triadof Hutchinson's teeth (notched incisors), keratitis and deafness.[21][22]

Symptoms include:[21]

- Blunted upper incisor teeth known asHutchinson's teeth,ormulberry molars[7]

- Deafnessfrom auditory nerve disease

- Frontal bossing (prominence of the brow ridge)[7]

- Hardpalatedefect

- Inflammation of the cornea known as interstitialkeratitis

- Protruding mandible

- Saber shins

- Saddle nose(collapse of the bony part of nose)

- Short maxillae

- Swollen knees

Treatment (with penicillin) before the development of late symptoms is essential.[23]

Clinical signs include:

- Abnormal bonex-rays[7]

- Anemia[24]

- Cerebral palsy

- Du Bois sign,shortening of the little finger[25]

- Enlarged liver[1]

- Enlarged spleen[1]

- Frontalbossing[7]

- Sensorineuralhearing loss

- Higouménakis' sign,enlargement of the sternal end of clavicle in late congenital syphilis, mostly on the right-hand side[26]

- Hutchinson's triad,a set of symptoms consisting ofdeafness,Hutchinson's teeth(centrally notched, widely spaced peg-shaped upper centralincisors), and interstitialkeratitis(IK), an inflammation of the cornea which can lead to corneal scarring and potential blindness[27]

- Hydrocephalus

- Jaundice[7]

- Lymph node enlargement[7]

- Mulberry molars(permanent first molars with multiple poorly developed cusps)[28][7]

- Musculoskeletal deformities

- Petechiae

- Poorly developedmaxillae[7]

- Pseudoparalysis[citation needed]

- Rhagades,linear scars at the angles of the mouth and nose result from bacterial infection of skin lesions

- Snuffles,aka "syphilitic rhinitis", which appears similar to the rhinitis of the common cold, except it is more severe, lasts longer, often involves bloody rhinorrhea, and is often associated with laryngitis[29]

- Sabre shins,malformation of the tibia[30]

- Skin rashor other skin changes such asrhagades[1][7]

Death from congenital syphilis is usually due tobleeding into the lungs.[citation needed]

Transmission

[edit]Syphilis may be transmitted from mother to the fetus during any stage of pregnancy.[18]It is most commonly transmitted via cross placental transfer ofTreponema pallidumbacteria from mother to the fetus during pregnancy with transmission via exposure to genital lesions during childbirth being less common.[18]The highest rate of transmission occurs in mothers with early syphilis (infection present for less than 1 year), which is responsible for 50-70% of infections, with syphilis being present for more than 1 year thought to be responsible for about 15% of transmission.[18]It is not transmitted duringbreastfeedingunless there is anopen soreon the mother'sbreast.[4]

Diagnosis

[edit]Direct observation ofTreponema pallidumfrom one of the lesions in the mother or infant is diagnostic and can be carried out usingdark field microscopy,direct fluorescent antibodytesting orimmunohistochemical staining,however these tests are not readily available in many settings.[18]Serological testing is more commonly carried out on the mother and the infant to diagnose maternal and congenital syphilis. In the mother, a serologic diagnosis of syphilis is made using anontreponemal testfor syphilis such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test (VDRL) orRapid plasma reagin(RPR) followed by a treponemal test, such as theTreponema pallidumparticle agglutination assay(TP-PA) (the sequence of testing may be reversed with a treponemal test followed by a non-treponemal test in the reverse diagnostic sequence).[18]Positivity of both tests indicates active syphilis or previous infection that was treated.[18]Quantitative non-treponemal tests are monitored for disease activity and response to treatment, with RPR is expected to decrease by a factor of four compared to pre-treatment levels after successful treatment of syphilis in the mother.[18]Failure of non-treponemal titers to decrease after treatment may indicate treatment failure or re-infection.[18]A confirmed cure in the mother does not exclude the possibility of congenital syphilis as transmission to the fetus may have occurred prior to maternal cure.[18]

Diagnosis of congenital syphilis in the fetus is based on a combination of laboratory, imaging and physical exam findings. Ultrasound findings associated with congenital syphilis intrauterine infection (which are seen after 18 weeks gestation) include fetalhepatomegaly(enlarged liver)(seen in greater than 80% of cases), anemia (as measured by the peak systolic velocity of the middle cerebral artery)(33%),placentomegaly(an enlarged placenta)(27%),polyhydramnios(an excess of amniotic fluid in the amniotic sac)(12%) andhydrops fetalis(edema in the fetus)(10%).[18]The absence of these ultrasound findings does not rule out congenital syphilis in the fetus.[18]These ultrasound abnormalities usually resolve several weeks after successful treatment of syphilis in the mother.[18]

Immunohistochemical staining ornucleic acid amplificationof the amniotic fluid may also aid in the diagnosis.[18]Diagnosis of syphilis in the neonate may be challenging as maternal treponemal antibodies (as non-treponemal titers) can cross the placenta and persist in the infant for many months after birth in the absence of neonatal syphilis, complicating the diagnosis.[18]The passively transferred non-treponemal titers should be cleared from the infant within 15 months of birth (with most titers being cleared by 6 months), and persistently elevated titers 6 months after birth should prompt investigation into neonatal syphilis includingCSFanalysis for neurosyphilis. Pleocytosis, raised CSF protein level and positive CSF serology suggest neurosyphilis.[31]CSF VDRL is 50-90% specific for neurosyphilis.[18]60% of newborns with congenital syphilis also have neurosyphilis.[18]Non-treponemal titers should be monitored in the newborns every 2-3 months to ensure an adequate response to treatment.[18]

Treatment

[edit]

If a pregnant mother is identified as being infected with syphilis, treatment can effectively prevent congenital syphilis from developing in the fetus, especially if she is treated before the sixteenth week of pregnancy or at least 30 days prior to delivery.[18][2]Mothers with primary syphilis can be treated with a single dose ofintramuscularlyinjected penicillin, whereas late-latent, secondary syphilis, or disease of an unknown duration is treated with once weekly penicillin injections for three weeks.[18]The mother's partner should also be evaluated and treated.[18]

The fetus is at greatest risk of contracting syphilis when the mother is in the early stages of infection, but the disease can be passed at any point during pregnancy, even during delivery. An affected child can be treated using antibiotics much like an adult; however, any developmental symptoms are likely to be permanent.[32]

The greater the duration between theinfectionof the mother andconception,the better the outcome for theinfantincluding less chance of stillbirth or developing congenital syphilis.[33]

TheCenters for Disease Control and Preventionrecommends treating symptomatic or babies born to an infected mother with unknown treatment status with procaine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg dose IM a day in a single dose for 10 days.[34]Treatment for these babies can vary on a case-by-case basis. Treatment cannot reverse any deformities, brain, or permanent tissue damage that has already occurred.[32]

ACochrane reviewfound that antibiotics may be effective for serological cure but in general the evidence around the effectiveness of antibiotics for congenital syphilis is uncertain due to the poor methodological quality of the small number of trials that have been conducted.[35]

Up to 40% of pregnant women treated for congenital syphilis will develop aJarisch-Herxheimer reaction,which is a temporary reaction that usually occurs within a few hours of starting penicillin and resolves by 24 hours. The reaction is characterized by cramping, fever, muscle aches and a rash. Treatment is supportive andfetal heart rate monitoringis recommended.[18]

Epidemiology

[edit]Syphilis affects around one million pregnancies a year.[13]In 2016, there were around 473 cases of congenital syphilis per 100,000 live births and 204,000 deaths from the disease worldwide.[14]Of the 660,000 congenital syphilis cases reported in 2016, 143,000 resulted in deaths of unborn babies, 61,000 deaths of newborn babies, 41,000 low birth weights or preterm births, and 109,000young childrendiagnosed with congenital syphilis.[15]Around 75% were from the WHO's African and Eastern Mediterranean regions.[2]

Cases of congenital syphilis in the United States have been rising since the early 2010s. TheCenters for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) reported 918 cases for 2017, which is more than twice the yearly incidence of the preceding four years.[36]The incidence in the United States has increased by 754% from 2012 to 2021 with a higher incidence seen in those with a lower socioeconomic status, as well as Black people, Native Americans and Native Hawaiians.[18]Reports in 2023 show a rise of more than 900 percent inMississippiover the preceding five years.[37]

History

[edit]Congenital syphilis was first described in Europe during the fifteenth century by the Spanish physicianGaspar Torrella.[18][38]Nineteenth century physicians held the belief that congenital syphilis was contracted from contaminated semen at time of conception.[16]Serological tests for syphilis were introduced in 1906, and it was later shown that transmission occurred from the mother.[16]

References

[edit]- ^abcdefGhanem, Khalil G.; Hook, Edward W. (2020)."303. Syphilis".In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.).Goldman-Cecil Medicine.Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 1986.ISBN978-0-323-55087-1.

- ^abcdefghiAdamson, Paul C.; Klausner, Jeffrey D. (2022)."60. Syphilis (Treponema palladium) ".In Jong, Elaine C.; Stevens, Dennis L. (eds.).Netter's Infectious Diseases(2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 339–347.ISBN978-0-323-71159-3.

- ^abcFerri, Fred F. (2022)."Syphilis".Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2022.Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 1452–1454.ISBN978-0-323-75571-9.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstMedoro, Alexandra K.; Sánchez, Pablo J. (June 2021)."Syphilis in Neonates and Infants".Clinics in Perinatology.48(2): 293–309.doi:10.1016/j.clp.2021.03.005.ISSN1557-9840.PMID34030815.S2CID235200042.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-07-20.Retrieved2023-05-10.

- ^abJames, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020)."18. Syphilis, Yaws, Bejel, and Pinta".Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology(13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. pp. 347–361.ISBN978-0-323-54753-6.

- ^ab"STD Facts - Congenital Syphilis".www.cdc.gov.10 April 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2023.Retrieved9 May2023.

- ^abcdefghijCooper, Joshua M; Sánchez, Pablo J (2018). "Congenital syphilis".Seminars in Perinatology.42(3): 178.doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2018.02.005.PMID29627075.

- ^Gilmour, Leeyan S.; Walls, Tony (15 March 2023)."Congenital Syphilis: a Review of Global Epidemiology".Clinical Microbiology Reviews.36(2): e0012622.doi:10.1128/cmr.00126-22.ISSN1098-6618.PMC10283482.PMID36920205.S2CID257535283.

- ^"Congenital Syphilis".Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 April 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 13 April 2023.Retrieved12 May2023.

- ^abcde"Congenital Syphilis - STI Treatment Guidelines".www.cdc.gov.19 October 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 1 April 2023.Retrieved9 May2023.

- ^WHO guideline on syphilis screening and treatment for pregnant women.Geneva: World health Organization. 2017.ISBN978-92-4-155009-3.

- ^Chastain, DB; Hutzley, VJ; Parekh, J; Alegro, JVG (9 August 2019)."Antimicrobial Desensitization: A Review of Published Protocols".Pharmacy.7(3): 112.doi:10.3390/pharmacy7030112.PMC6789802.PMID31405062.

- ^abHussain, Syed A.; Vaidya, Ruben (2023)."Congenital Syphilis".StatPearls.StatPearls Publishing.PMID30725772.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-12-10.Retrieved2023-05-12.

- ^abGlobal progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021(PDF).Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021.ISBN978-92-4-003098-5.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2023-03-26.Retrieved2023-05-08.

- ^ab"Congenital syphilis - Mother-to-child transmission of syphilis".www.who.int.Archivedfrom the original on 21 April 2023.Retrieved9 May2023.

- ^abcOriel, J. David (2012)."5." The sins of the fathers ": Congenital syphilis".The Scars of Venus: A History of Venereology.London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 69–70.ISBN978-1-4471-2068-1.

- ^abc"Congenital syphilis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia".medlineplus.gov.Retrieved2021-11-17.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyStafford, Irene A.; Workowski, Kimberly A.; Bachmann, Laura H. (18 January 2024). "Syphilis Complicating Pregnancy and Congenital Syphilis".New England Journal of Medicine.390(3): 242–253.doi:10.1056/NEJMra2202762.PMID38231625.

- ^abTsimis, Michael E.; Sheffield, Jeanne S. (2017-03-15)."Update on syphilis and pregnancy".Birth Defects Research.109(5): 347–352.doi:10.1002/bdra.23562.ISSN2472-1727.PMID28398683.S2CID1026966.

- ^Finsh, RG; Irving, WL; Moss, P; Anderson, J (2009). "Infectious diseases, tropical medicine and sexually transmitted infection". In Kumar, Parveen; Clark, Michael (eds.).Kumar & Clark's Clinical Medicine(7 ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 178.ISBN978-0-7020-2993-6.

- ^ab"Congenital Syphilis".University of Pittsburgh.

- ^Pessoa, Larissa; Galvão, Virgilio (2011)."Clinical aspects of congenital syphilis with Hutchinson's triad".Case Reports.2011:bcr1120115130.doi:10.1136/bcr.11.2011.5130.PMC3246168.PMID22670010.

- ^"Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines - 2002".Cdc.gov.Retrieved2013-01-21.

- ^"Anemia: Overview".The Lecturio Medical Concept Library.Retrieved28 June2021.

- ^Voelpel, James H.; Muehlberger, Thomas (1 March 2011). "The du Bois Sign".Annals of Plastic Surgery.66(3): 241–244.doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181ea1ed8.PMID21263293.

- ^Frangos, Constantinos C; Lavranos, Giagkos M; Frangos, Christos C (2011)."Higoumenakis' sign in the diagnosis of congenital syphilis in anthropological specimens".Med Hypotheses.77(1): 128–31.doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2011.03.044.

- ^Pessoa, Larissa; Galvão, Virgilio (2011)."Clinical aspects of congenital syphilis with Hutchinson's triad".Case Reports.2011:bcr1120115130.doi:10.1136/bcr.11.2011.5130.PMC3246168.PMID22670010.

- ^Hillson, S; Grigson, C; Bond, S (1998). "Dental defects of congenital syphilis".Am J Phys Anthropol.107(1): 25–40.doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199809)107:1<25::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-C.ISSN0002-9483.PMID9740299.

- ^Darville, T. (1 May 1999). "Syphilis".Pediatrics in Review.20(5): 160–165.doi:10.1542/pir.20-5-160.PMID10233174.

- ^Pineda, Carlos; Mansilla-Lory, Josefina; Martínez-Lavín, Manuel; Leboreiro, Ilán; Izaguirre, Aldo; Pijoan, Carmen (2009). "Rheumatic Diseases in the Ancient Americas: The Skeletal Manifestations of Treponematoses".JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology.15(6): 280–283.doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181b0c848.PMID19734732.

- ^South, Mike (2012).Practical Paediatrics(7th ed.). Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. pp. 368, 830.ISBN9780702042928.

- ^abArnold, S; Ford-Jones, L (November–December 2000)."Congenital syphilis: A guide to diagnosis and management".Paediatrics & Child Health.5(8): 463–469.doi:10.1093/pch/5.8.463.PMC2819963.PMID20177559.

- ^Singh, Ameeta E.; Romanowski, Barbara (1 April 1999)."Syphilis: Review with Emphasis on Clinical, Epidemiologic, and Some Biologic Features".Clinical Microbiology Reviews.12(2): 187–209.doi:10.1128/CMR.12.2.187.PMC88914.PMID10194456.

- ^"Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Treatment Guidelines, 2010 By: the CDC".RetrievedJuly 21,2019.

- ^Walker, GJ; Walker, D; Molano Franco, D; Grillo-Ardila, CF (15 February 2019)."Antibiotic treatment for newborns with congenital syphilis".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2019(2): CD012071.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012071.pub2.PMC6378924.PMID30776081.

- ^"A Devastating Surge in Congenital Syphilis: How Can We Stop It?".Medscape.Retrieved2023-02-15.

- ^Yang, Maya (2023-02-12)."Mississippi sees 900% rise in number of infants born with congenital syphilis".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved2023-02-15.

- ^Dendi, Alvaro; Sobrero, Helena; Mattos Castellano, María; Maheshwari, Akhil (2024). "Congenital Syphilis".Principles of Neonatology:274–278.doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-69415-5.00034-5.ISBN978-0-323-69415-5.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related toCongenital syphilisat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toCongenital syphilisat Wikimedia Commons