Conium maculatum

| Conium maculatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conium maculatuminCalifornia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Apiaceae |

| Genus: | Conium |

| Species: | C. maculatum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Conium maculatum L.,1753

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

Conium maculatum,known ashemlock(British English),[2]orpoison hemlock(American English)[3]is a highly poisonousflowering plantin the carrot familyApiaceae,native toEuropeandNorth Africa.It isherbaceouswithout woody parts and has abienniallifecycle. A hardy plant capable of living in a variety of environments, hemlock is widely naturalised in locations outside its native range, such as parts of Australia, West Asia, and North and South America, to which it has been introduced. It is capable of spreading and thereby becoming aninvasiveweed.

All parts of the plant aretoxic,especially the seeds and roots, and especially when ingested. Under the right conditions the plant grows quite rapidly during the growing season and can reach heights of 2.4 metres (8 feet), with a longpenetrating root.The plant has a distinctive odour usually considered unpleasant that carries with the wind. The hollow stems are usually spotted with a dark maroon colour and become dry and brown after completing itsbienniallifecycle. The hollow stems of the plant are deadly for up to three years after the plant has died.[4]

Description

[edit]Conium maculatumis a herbaceousflowering plantthat grows to 1.5–2.5 metres (5–8 feet) tall, exceptionally 3.6 m (12 ft).[5]All parts of the plant are hairless (glabrous). Hemlock has a smooth, green, hollow stem, usually spotted or streaked with red or purple. Theleavesare two- to four-pinnate,finely divided and lacy, overall triangular in shape, up to 50 centimetres (20 inches) long and 40 cm (16 in) broad.[6]Hemlock's flower is small and white; they are loosely clustered and each flower has five petals.[7]

Abiennial plant,hemlock produces leaves at its base the first year but no flowers. In its second year it produces white flowers in umbrella-shaped clusters.[8]

-

19th-century illustration

-

Vertically growing specimen

-

Specimen inChino, California

-

Flowers

-

Seed heads in late summer

Similar species

[edit]Hemlock can be confused with the wild carrot plant (Daucus carota,sometimes called Queen Anne's lace). Wild carrot has a hairy stem without purple markings, and grows less than1 m (3+1⁄2ft) tall.[9]One can distinguish the two from each other by hemlock's smooth texture, vivid mid-green colour, purple spotting of stems and petioles and typical height of the flowering stems being at least 1.5 m (5 ft) twice the maximum for wild carrot. Wild carrots have hairy stems that lack the purple blotches.[10][11] The species can also be confused with harmless cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris,also sometimes called Queen Anne's lace).[8][12]

The plant should not be visually confused with the North American-nativeTsuga,a coniferous tree sometimes called the hemlock, hemlock fir, or hemlock spruce, from a slight similarity in the leaf smell. The ambiguous shorthand of 'hemlock' for this tree is more common in the US dialect than the plant it is actually named after.[citation needed]Similarly, the plant should not be confused withCicuta(commonly known as water hemlock).[12]

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus name "Conium" refers tokoneios,the Greek word for 'spin' or 'whirl', alluding to thedizzying effectsof the plant's poison after ingestion. In the vernacular, "hemlock" most commonly refers to the speciesC. maculatum.Coniumcomes from theAncient Greekκώνειον – kṓneion:"hemlock". This may be related tokonas(meaning to whirl), in reference tovertigo,one of the symptoms of ingesting the plant.[13]

C. maculatum,also known as poison hemlock, was the first species within the genus to be described. It was identified byCarl Linnaeusin his 1753 publication,Species Plantarum.Maculatummeans 'spotted', in reference to the purple blotches characteristic of the stalks of the species.[14]

Names

[edit]Vernacular namesin the English language are hemlock (British English), poison hemlock (American English), poison parsley, spotted corobane (rarer forms), carrot fern (Australian Eng.), devil's bread or devil's porridge (IrishEng.)[15]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The hemlock plant is native toEuropeand theMediterranean region.[16]

It exists in some woodland (and elsewhere) in mostBritish Islescounties;[17]inUlsterthese are particularlyCounty Down,County AntrimandCounty Londonderry.[18]

It has become naturalised in Asia, North America, Australia and New Zealand.[19][20][15]It is sometimes encountered around rivers insoutheast AustraliaandTasmania.[21]Infestations and human contact with the plant are sometimes newsworthy events in the U.S. due toits extreme toxicity.[22][23]

Ecology

[edit]The plant is often found in poorly drained soil, particularly near streams, ditches, and other watery surfaces. It also appears on roadsides, edges of cultivated fields, and waste areas.[19]Conium maculatumgrows in quite damp soil,[2]but also on drier rough grassland, roadsides and disturbed ground. It is used as a food plant by thelarvaeof somelepidoptera,includingsilver-ground carpetmoths and particularly the poison hemlock moth (Agonopterix alstroemeriana). The latter has been widely used as a biological control agent for the plant.[24]Hemlock grows in the spring, when much undergrowth is not in flower and may not be in leaf. All parts of the plant are poisonous.[3]

Toxicity

[edit]Hemlock containsconiineand some similar poisonousalkaloids,and is poisonous to all mammals (and many other organisms) that eat it. Intoxication has been reported in cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, donkeys, rabbits, and horses. Ingesting more than 150–300 milligrams of coniine, approximately equivalent to six to eight hemlock leaves, can be fatal for adult humans.[25]The seeds and roots are more toxic than the leaves.[26]Farmers also need to ensure that the hay fed to their animals does not contain hemlock. Hemlock is most poisonous in the spring when the concentration of γ-coniceine (the precursor to other toxins) is at its peak.[27][28]

Alkaloids

[edit]

C. maculatumis known for being extremely poisonous. Its tissues contain a number of differentalkaloids.In flower buds, the major alkaloid found is γ-coniceine. This molecule is transformed into coniine later during the fruit development.[30]The alkaloids are volatile; as such, researchers assume that these alkaloids play an important role in attractingpollinatorssuch as butterflies and bees.[31]

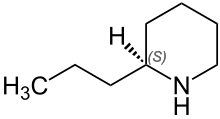

Coniumcontains thepiperidine alkaloidsconiine,N-methylconiine,conhydrine,pseudoconhydrine and gamma-coniceine (or g-coniceïne), which is the precursor of the other hemlock alkaloids.[19][32][33][34]

Coniine has pharmacological properties and a chemical structure similar tonicotine.[19][35]Coniine acts directly on thecentral nervous systemthrough inhibitory action onnicotinic acetylcholine receptors.Coniine can be dangerous tohumansandlivestock.[33]With its high potency, the ingestion of seemingly small doses can easily result in respiratory collapse and death.[36]

The alkaloid content inC. maculatumalso affects the thermoregulatory centre by a phenomenon calledperipheral vasoconstriction,resulting in hypothermia in calves.[37]In addition, the alkaloid content was also found to stimulate thesympathetic gangliaand reduce the influence of theparasympathetic gangliain rats and rabbits, causing an increased heart rate.[38]

Coniine also has significant toxic effects on the kidneys. The presence ofrhabdomyolysisandacute tubular necrosishas been shown in patients who died from hemlock poisoning. A fraction of these patients were also found to haveacute kidney injury.[39]Coniine is toxic for the kidneys because it leads to the constriction of the urinarybladder sphincterand eventually the accumulation of urine.[40]

Toxicology

[edit]A short time after ingestion, the alkaloids induce potentially fatal neuromuscular dysfunction due to failure of therespiratory muscles.Acute toxicity,if not lethal, may resolve in spontaneous recovery, provided further exposure is avoided. Death can be prevented byartificial ventilationuntil the effects have worn off 48–72 hours later.[19]For an adult, the ingestion of more than 100 mg (0.1 gram) of coniine (about six to eight fresh leaves, or a smaller dose of the seeds or root) may be fatal. Narcotic-like effects can be observed as soon as 30 minutes after ingestion of green leaf matter of the plant, with victims falling asleep and unconsciousness gradually deepening until death a few hours later.[41]

The onset of symptoms is similar to that caused bycurare,with an ascending muscular paralysis leading to paralysis of the respiratory muscles, causing death from oxygen deprivation.[42]

It has been observed that poisoned animals return to feed on the plant after initial poisoning.Chronic toxicityaffects only pregnant animals when they are poisoned at low levels byC. maculatumduring the fetus' organ-formation period; in such cases the offspring is born withmalformations,mainlypalatoschisisand multiple congenital contractures (arthrogryposis). The damage to the fetus due to chronic toxicity is irreversible. Though arthrogryposis may be surgically corrected in some cases, most of the malformed animals die. Such losses may be underestimated, at least in some regions, because of the difficulty in associating malformations with the much earlier maternal poisoning.

Since no specific antidote is available, prevention is the only way to deal with the production losses caused by the plant. Control withherbicidesand grazing with less-susceptible animals (such assheep) have been suggested. It is a common myth thatC. maculatumalkaloids can enter the human food chain viamilkandfowl,and scientific studies have disproven these claims.[43]

Culture

[edit]

In ancient Greece, hemlock was used to poison condemned prisoners.Conium maculatumis the plant that killedTheramenes,Socrates,Polemarchus,andPhocion.[44]Socrates, the most famous victim of hemlock poisoning, was accused ofimpietyand corrupting the minds of the young men of Athens in 399 BC, and his trial gave down his death sentence. He decided to take a potentinfusionof hemlock.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Allkin, R.; Magill, R.; et al., eds. (2013)."Conium maculatumL. "The Plant List(online database). 1.1.RetrievedJanuary 23,2017.

- ^ab"Online Atlas of the British and Irish Flora:Conium maculatum".Archivedfrom the original on 2014-07-14.Retrieved2014-08-07.

- ^ab"Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)".Agricultural Research Service.U.S. Department of Agriculture. 26 June 2018.Retrieved30 January2024.

- ^Duggan, Scott (2018-06-01)."Poison hemlock and Western waterhemlock: deadly plants that may be growing in your pasture".Ag - Forages/Pastures.

- ^"Poison Hemlock".pierecountryweedboard.wsu.edu.Pierce County Noxious Weed Control Board. Archived fromthe originalon 2021-12-08.Retrieved2020-05-12.

- ^"Altervista Flora Italiana,Cicuta maggiore,Conium maculatumL. includes photos and European distribution map ".Archivedfrom the original on 2015-06-15.Retrieved2015-06-13.

- ^Holm, LeRoy G. (1997).World weeds: natural histories and distribution.New York: Wiley.ISBN0471047015.

- ^ab"Poison Hemlock"(PDF).store.msuextension.org.Montana State University.Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^DNRP-WLRD-RRS Staff (November 28, 2016)."Poison-hemlock".Noxious Weeds in King County, Weed Identification Photos.Seattle, WA: Department of Natural Resources and Parks (DNRP), Water and Land Resources Division (WLRD), Rural and Regional Services (RRS) section.RetrievedJanuary 23,2017.

- ^Nyerges, Christopher (2017).Foraging Washington: Finding, Identifying, and Preparing Edible Wild Foods.Guilford, CT: Falcon Guides.ISBN978-1-4930-2534-3.OCLC965922681.

- ^"How to Tell the Difference Between Poison Hemlock and Queen Anne's Lace".2 July 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-19.Retrieved2021-05-03.

- ^ab"Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum)".USDA Agricultural Research Service.

- ^"Conium maculatum".Northwestern Arizona University. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-06-23.Retrieved2012-07-06.

- ^"Conium maculatum (poison hemlock)".www.cabi.org.Retrieved2020-12-03.

- ^ab"Atlas of Living Australia,Conium maculatumL., Carrot Fern ".Archived fromthe originalon 2015-09-19.Retrieved2015-06-13.

- ^Vetter, J (September 2004). "Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatumL.) ".Food Chem Toxicol.42(9): 1374–82.doi:10.1016/j.fct.2004.04.009.PMID15234067.

- ^Clapham, A.R.; Tutin, T.G.; Warburg, E.F. (1968).Excursion Flora of the British Isles(2nd ed.).ISBN0521-04656-4.

- ^Hackney, P., ed. (1992).Stewart & Corry's Flora of the North-east of Ireland.Institute of Irish Studies and The Queen's University of Belfast.ISBN0-85389-446-9.

- ^abcdeSchep, L. J.; Slaughter, R. J.; Beasley, D. M. (2009). "Nicotinic Plant Poisoning".Clinical Toxicology.47(8): 771–781.doi:10.1080/15563650903252186.PMID19778187.S2CID28312730.

- ^Zehui, Pan & Watson, Mark F."31.ConiumLinnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 243. 1753 ".Flora of China.RetrievedJanuary 23,2017.See also the substituent page:"1.Conium maculatumLinnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 243. 1753 ".Flora of China.RetrievedJanuary 23,2017.

- ^"Hemlock, Carrot Fern, Poison Hemlock, Poison Parsley, Spotted Hemlock, Wild Carrot, Wild Parsnip".Weeds Australia - profiles.Centre for Invasive Species Solutions (CISS). 2021.Retrieved30 January2024.

- ^"Poison Hemlock".Archivedfrom the original on 2022-11-29.Retrieved2022-11-29.

- ^Adatia, Noor (2023-06-03)."Poison hemlock was spotted in a Dallas suburb. Here's what you should know about the plant".The Dallas Morning News.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-06-03.Retrieved2023-06-03.

- ^Castells, Eva; Berenbaum, May R. (June 2006)."Laboratory Rearing ofAgonopterix alstroemeriana,the Defoliating Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatumL.) Moth, and Effects of Piperidine Alkaloids on Preference and Performance ".Environmental Entomology.35(3): 607–615.doi:10.1603/0046-225x-35.3.607.S2CID45478867.

- ^Hotti, Hannu; Rischer, Heiko (2017-11-14)."The killer of Socrates: Coniine and Related Alkaloids in the Plant Kingdom".Molecules.22(11): 1962.doi:10.3390/molecules22111962.ISSN1420-3049.PMC6150177.PMID29135964.

- ^IPCS INCHEM: International Programme on Chemical Safety.1997-07-01.

- ^Cheeke, Peter (31 Aug 1989).Toxicants of Plant Origin: Alkaloids, Volume 1(1 ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 118.ISBN978-0849369902.

- ^"Poison Hemlock: Options for Control"(PDF).co.lincoln.wa.us.Lincoln County Noxious Weed Control Board. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 March 2016.Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^Stephen T. Lee; Benedict T. Green; Kevin D. Welch; James A. Pfister; Kip E. Panter (2008). "Stereoselective potencies and relative toxicities of coniine enantiomers".Chemical Research in Toxicology.21(10): 2061–2064.doi:10.1021/tx800229w.PMID18763813.

- ^Cromwell, B. T. (October 1956)."The separation, micro-estimation and distribution of the alkaloids of hemlock (Conium maculatumL.) ".Biochemical Journal.64(2): 259–266.doi:10.1042/bj0640259.ISSN0264-6021.PMC1199726.PMID13363836.

- ^Roberts, Margaret F. (1998), "Enzymology of Alkaloid Biosynthesis",Alkaloids,Springer US, pp. 109–146,doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2905-4_5,ISBN9781441932631

- ^Reynolds, T. (June 2005). "Hemlock Alkaloids from Socrates to Poison Aloes".Phytochemistry.66(12): 1399–1406.doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.04.039.PMID15955542.

- ^abVetter, J. (September 2004). "Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatumL.) ".Food and Chemical Toxicology.42(9): 1373–1382.doi:10.1016/j.fct.2004.04.009.PMID15234067.

- ^"Conium maculatumTOXINZ - Poisons Information ".www.toxinz.com.Archived fromthe originalon 2017-05-23.Retrieved2017-05-29.

- ^Brooks, D. E. (2010-06-28)."Plant Poisoning, Hemlock".MedScape.eMedicine.Retrieved2012-03-02.

- ^Tilford, Gregory L. (1997).Edible and Medicinal Plants of the West.ISBN978-0-87842-359-0.

- ^López, T.A.; Cid, M.S.; Bianchini, M.L. (June 1999). "Biochemistry of hemlock (Conium maculatumL.) alkaloids and their acute and chronic toxicity in livestock. A review ".Toxicon.37(6): 841–865.doi:10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00204-9.ISSN0041-0101.PMID10340826.

- ^Forsyth, Carol S.; Frank, Anthony A. (July 1993). "Evaluation of developmental toxicity of coniine to rats and rabbits".Teratology.48(1): 59–64.doi:10.1002/tera.1420480110.ISSN0040-3709.PMID8351649.

- ^Rizzi, D; Basile, C; Di Maggio, A; et al. (1991). "Clinical spectrum of accidental hemlock poisoning: neurotoxic manifestations, rhabdomyolysis and acute tubular necrosis".Nephrol. Dial. Transplant.6(12): 939–43.doi:10.1093/ndt/6.12.939.PMID1798593.

- ^Barceloux, Donald G. (2008), "Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatumL.) ",Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals,John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 796–799,doi:10.1002/9780470330319.ch131,ISBN9780470330319

- ^Drummer, Olaf H.; Roberts, Anthony N.; Bedford, Paul J.; Crump, Kerryn L.; Phelan, Michael H. (1995)."Three deaths from hemlock poisoning".The Medical Journal of Australia.162(5): 592–593.doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb138553.x.PMID7791646.S2CID45736238.

- ^"Conium maculatumL. "Inchem.IPCS (International Programme on Chemical Safety).Retrieved2012-07-06.

- ^Frank, A. A.; Reed, W.M. (April 1990). "Comparative Toxicity of Coniine, an Alkaloid ofConium maculatum(Poison Hemlock), in Chickens, Quails, and Turkeys ".Avian Diseases.34(2): 433–437.doi:10.2307/1591432.JSTOR1591432.PMID2369382.

- ^Blamey, M.; Fitter, R.; Fitter, A. (2003).Wild flowers of Britain and Ireland: The Complete Guide to the British and Irish Flora.London: A & C Black.ISBN978-1408179505.

External links

[edit] Media related toConium maculatumat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toConium maculatumat Wikimedia Commons- "Conium".Flora Europaea.Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.