Birth control

Birth control,also known ascontraception,anticonception,andfertility control,is the use of methods or devices to preventunintended pregnancy.[1]Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only became available in the 20th century.[2]Planning, making available, and using human birth control is calledfamily planning.[3][4]Some cultures limit or discourage access to birth control because they consider it to be morally, religiously, or politically undesirable.[2]

TheWorld Health OrganizationandUnited States Centers for Disease Control and Preventionprovide guidance on the safety of birth control methods among women with specific medical conditions.[5][6]The most effective methods of birth control aresterilizationby means ofvasectomyin males andtubal ligationin females,intrauterine devices(IUDs), andimplantable birth control.[7]This is followed by a number ofhormone-based methodsincludingoral pills,patches,vaginal rings,andinjections.[7]Less effective methods includephysical barrierssuch ascondoms,diaphragmsandbirth control spongesandfertility awareness methods.[7]The least effective methods arespermicidesandwithdrawal by the male before ejaculation.[7]Sterilization, while highly effective, is not usually reversible; all other methods are reversible, most immediately upon stopping them.[7]Safe sexpractices, such as with the use of male orfemale condoms,can also help preventsexually transmitted infections.[8]Other methods of birth control do not protect against sexually transmitted infections.[9]Emergency birth controlcan prevent pregnancy if taken within 72 to 120 hours after unprotected sex.[10][11]Some arguenot having sexis also a form of birth control, butabstinence-only sex educationmay increaseteenage pregnanciesif offered without birth control education, due to non-compliance.[12][13]

Inteenagers,pregnancies are at greater risk of poor outcomes.[14]Comprehensivesex educationand access to birth control decreases the rate of unintended pregnancies in this age group.[14][15]While all forms of birth control can generally be used by young people,[16]long-acting reversible birth controlsuch as implants, IUDs, or vaginal rings are more successful in reducing rates of teenage pregnancy.[15]After the delivery of a child, a woman who is not exclusively breastfeeding may become pregnant again after as few as four to six weeks.[16]Some methods of birth control can be started immediately following the birth, while others require a delay of up to six months.[16]In women who are breastfeeding,progestin-only methodsare preferred overcombined oral birth control pills.[16]In women who have reachedmenopause,it is recommended that birth control be continued for one year after the lastmenstrual period.[16]

About 222 million women who want to avoid pregnancy indeveloping countriesare not using a modern birth control method.[17][18]Birth control use in developing countries has decreased the number ofdeaths during or around the time of pregnancyby 40% (about 270,000 deaths prevented in 2008) and could prevent 70% if the full demand for birth control were met.[19][20]By lengthening the time between pregnancies, birth control can improve adult women's delivery outcomes and the survival of their children.[19]In the developing world, women's earnings, assets, and weight, as well as their children's schooling and health, all improve with greater access to birth control.[21]Birth control increases economic growth because of fewer dependent children, more women participating in theworkforce,and/or less use of scarce resources.[21][22]

Methods[edit]

| Method | Typical use | Perfect use |

|---|---|---|

| No birth control | 85% | 85% |

| Combination pill | 9% | 0.3% |

| Progestin-only pill | 13% | 1.1% |

| Sterilization (female) | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Sterilization (male) | 0.15% | 0.1% |

| Condom (female) | 21% | 5% |

| Condom (male) | 18% | 2% |

| Copper IUD | 0.8% | 0.6% |

| Hormonal IUD | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Patch | 9% | 0.3% |

| Vaginal ring | 9% | 0.3% |

| MPAshot | 6% | 0.2% |

| Implant | 0.05% | 0.05% |

| Diaphragm and spermicide | 12% | 6% |

| Fertility awareness | 24% | 0.4–5% |

| Withdrawal | 22% | 4% |

| Lactational amenorrhea method (6 months failure rate) |

0–7.5%[25] | <2%[26] |

Birth control methods includebarrier methods,hormonal birth control,intrauterine devices(IUDs),sterilization,and behavioral methods. They are used before or during sex whileemergency contraceptivesare effective for up to five days after sex. Effectiveness is generally expressed as the percentage of women who become pregnant using a given method during the first year,[27]and sometimes as a lifetime failure rate among methods with high effectiveness, such astubal ligation.[28]

Birth control methods fall into two main categories:male contraceptionandfemale contraception.Common male contraceptives arewithdrawal,condoms,andvasectomy.Female contraception is more developed compared to male contraception, these includecontraceptive pills(combination and progestin-only pill), hormonal or non-hormonalIUD,patch,vaginal ring,diaphragm,shot,implant,fertility awareness,andtubal ligation.

The most effective methods are those that are long acting and do not require ongoing health care visits.[29]Surgical sterilization, implantable hormones, and intrauterine devices all have first-year failure rates of less than 1%.[23]Hormonal contraceptive pills, patches or vaginal rings, and thelactational amenorrhea method(LAM), if adhered to strictly, can also have first-year (or for LAM, first-6-month) failure rates of less than 1%.[29]With typical use, first-year failure rates are considerably higher, at 9%, due to inconsistent use.[23]Other methods such as condoms, diaphragms, and spermicides have higher first-year failure rates even with perfect usage.[29]TheAmerican Academy of Pediatricsrecommendslong acting reversible birth controlas first line for young individuals.[30]

While all methods of birth control have some potential adverse effects, the risk is less than that of pregnancy.[29]After stopping or removing many methods of birth control, including oral contraceptives, IUDs, implants and injections, the rate of pregnancy during the subsequent year is the same as for those who used no birth control.[31]

For individuals with specific health problems, certain forms of birth control may require further investigations.[32]For women who are otherwise healthy, many methods of birth control should not require amedical exam—including birth control pills, injectable or implantable birth control, and condoms.[33]For example, apelvic exam,breast exam,or blood test before starting birth control pills does not appear to affect outcomes.[34][35][36]In 2009, theWorld Health Organization(WHO) published a detailed list ofmedical eligibility criteriafor each type of birth control.[32]

Hormonal[edit]

Hormonal contraceptionis available in a number of different forms, includingoral pills,implantsunder the skin,injections,patches,IUDsand avaginal ring.They are currently available only for women, although hormonal contraceptives for men have been and are being clinically tested.[37]There are two types of oral birth control pills, thecombined oral contraceptive pills(which contain bothestrogenand aprogestin) and theprogestogen-only pills(sometimes called minipills).[38]If either is taken during pregnancy, they do not increase the risk ofmiscarriagenor causebirth defects.[35]Both types of birth control pills preventfertilizationmainly by inhibitingovulationand thickening cervical mucus.[39][40]They may also change the lining of the uterus and thus decrease implantation.[40]Their effectiveness depends on the user's adherence to taking the pills.[35]

Combined hormonal contraceptives are associated with a slightly increased risk ofvenousandarterial blood clots.[41]Venous clots, on average, increase from 2.8 to 9.8 per 10,000 women years[42]which is still less than that associated with pregnancy.[41]Due to this risk, they are not recommended in women over 35 years of age who continue to smoke.[43]Due to the increased risk, they are included in decision tools such as theDASH scoreandPERC ruleused to predict the risk of blood clots.[44]

The effect on sexual drive is varied, with increase or decrease in some but with no effect in most.[45]Combined oral contraceptives reduce the risk ofovarian cancerandendometrial cancerand do not change the risk of breast cancer.[46][47]They often reduce menstrual bleeding andpainful menstruation cramps.[35]The lower doses of estrogen released from the vaginal ring may reduce the risk of breast tenderness,nausea,and headache associated with higher dose estrogen products.[46]

Progestin-only pills, injections and intrauterine devices are not associated with an increased risk of blood clots and may be used by women with a history of blood clots in their veins.[41][48]In those with a history of arterial blood clots, non-hormonal birth control or a progestin-only method other than the injectable version should be used.[41]Progestin-only pills may improve menstrual symptoms and can be used by breastfeeding women as they do not affectmilk production.Irregular bleeding may occur with progestin-only methods, with some users reportingno periods.[49]The progestinsdrospirenoneanddesogestrelminimize theandrogenicside effects but increase the risks of blood clots and are thus not first line.[50]The perfect use first-year failure rate ofinjectable progestinis 0.2%; the typical use first failure rate is 6%.[23]

-

Three varieties ofbirth control pillsin calendar oriented packaging

-

Birth control pills

-

A transdermalcontraceptive patch

-

ANuvaRingvaginal ring

Barrier[edit]

Barrier contraceptivesare devices that attempt to prevent pregnancy by physically preventingspermfrom entering theuterus.[51]They include malecondoms,female condoms,cervical caps,diaphragms,andcontraceptive spongeswithspermicide.[51]

Globally, condoms are the most common method of birth control.[52]Male condomsare put on a man's erectpenisand physically block ejaculated sperm from entering the body of a sexual partner.[53]Modern condoms are most often made fromlatex,but some are made from other materials such aspolyurethane,or lamb's intestine.[53]Female condomsare also available, most often made ofnitrile,latex or polyurethane.[54]Male condoms have the advantage of being inexpensive, easy to use, and have few adverse effects.[55]Making condoms available to teenagers does not appear to affect the age of onset of sexual activity or its frequency.[56]In Japan, about 80% of couples who are using birth control use condoms, while in Germany this number is about 25%,[57]and in the United States it is 18%.[58]

Male condoms and the diaphragm with spermicide have typical use first-year failure rates of 18% and 12%, respectively.[23]With perfect use condoms are more effective with a 2% first-year failure rate versus a 6% first-year rate with the diaphragm.[23]Condoms have the additional benefit of helping to prevent the spread of some sexually transmitted infections such asHIV/AIDS,however, condoms made from animal intestine do not.[7][59]

Contraceptive sponges combine a barrier with a spermicide.[29]Like diaphragms, they are inserted vaginally before intercourse and must be placed over thecervixto be effective.[29]Typical failure rates during the first year depend on whether or not a woman has previously given birth, being 24% in those who have and 12% in those who have not.[23]The sponge can be inserted up to 24 hours before intercourse and must be left in place for at least six hours afterward.[29]Allergic reactions[60]and more severe adverse effects such astoxic shock syndromehave been reported.[61]

-

A rolled up malecondom.

-

A polyurethanefemale condom

-

Acontraceptive spongeset inside its open package.

Intrauterine devices[edit]

The currentintrauterine devices(IUD) are small devices, often T-shaped, containing either copper orlevonorgestrel,which are inserted into the uterus. They are one form oflong-acting reversible contraceptionwhich are the most effective types of reversible birth control.[62]Failure rates with thecopper IUDis about 0.8% while thelevonorgestrel IUDhas a failure rates of 0.2% in the first year of use.[63]Among types of birth control, they, along with birth control implants, result in the greatest satisfaction among users.[64]As of 2007[update],IUDs are the most widely used form of reversible contraception, with more than 180 million users worldwide.[65]

Evidence supports effectiveness and safety in adolescents[64]and those who have and have not previously had children.[66]IUDs do not affectbreastfeedingand can be inserted immediately after delivery.[67]They may also be used immediately after an abortion.[68][69]Once removed, even after long term use, fertility returns to normal immediately.[70]

Whilecopper IUDsmay increase menstrual bleeding and result in more painful cramps,[71]hormonal IUDsmay reduce menstrual bleeding or stop menstruation altogether.[67]Cramping can be treated with painkillers likenon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.[72]Other potential complications include expulsion (2–5%) and rarely perforation of the uterus (less than 0.7%).[67][72]A previous model of the intrauterine device (theDalkon shield) was associated with an increased risk ofpelvic inflammatory disease;however, the risk is not affected with current models in those withoutsexually transmitted infectionsaround the time of insertion.[73]IUDs appear to decrease the risk ofovarian cancer.[74]

Sterilization[edit]

Two broad categories exist, surgical and non-surgical.

Surgical sterilizationis available in the form oftubal ligationfor women andvasectomyfor men.[2]Tubal ligation decreases the risk ofovarian cancer.[2]Short term complications are twenty times less likely from a vasectomy than a tubal ligation.[2][75]After a vasectomy, there may be swelling and pain of the scrotum which usually resolves in one or two weeks.[76]Chronic scrotal pain associated with negative impact on quality of life occurs after vasectomy in about 1–2% of men.[77]With tubal ligation, complications occur in 1 to 2 percent of procedures with serious complications usually due to theanesthesia.[78]Neither method offers protection from sexually transmitted infections.[2]Sometimes,salpingectomyis also used for sterilization in women.[79]

Non-surgical sterilizationmethods have also been explored. Fahim[80][81][82]et al. found that heat exposure, especially high-intensity ultrasound, was effective either for temporary or permanent contraception depending on the dose, e.g. selective destruction of germ cells and Sertoli cells without affecting Leydig cells or testosterone levels. Chemical, e.g. drug-based methods are also available, e.g. orally-administered Lonidamine[83]for temporary, or permanent (depending on the dose) fertility management. Boris[84]provides a method for chemically inducing either temporary or non-reversible sterility, depending on the dose, "Permanent sterility in human males can be obtained by a single oral dosage containing from about 18 mg/kg to about 25 mg/kg".

The permanence of this decision may cause regret in some men and women. Of women who have undergone tubal ligation after the age of 30, about 6% regret their decision, as compared with 20–24% of women who received sterilization within one year of delivery and before turning 30, and 6% innulliparouswomen sterilized before the age of 30.[85]By contrast, less than 5% of men are likely to regret sterilization. Men who are more likely to regret sterilization are younger, have young or no children, or have an unstable marriage.[86]In a survey of biological parents, 9% stated they would not have had children if they were able to do it over again.[87]

Although sterilization is considered a permanent procedure,[88]it is possible to attempt atubal reversalto reconnect thefallopian tubesor avasectomy reversalto reconnect thevasa deferentia.In women, the desire for a reversal is often associated with a change in spouse.[88]Pregnancy success rates after tubal reversal are between 31 and 88 percent, with complications including an increased risk ofectopic pregnancy.[88]The number of males who request reversal is between 2 and 6 percent.[89]Rates of success in fathering another child after reversal are between 38 and 84 percent; with success being lower the longer the time period between the vasectomy and the reversal.[89]Sperm extractionfollowed byin vitro fertilizationmay also be an option in men.[90]

Behavioral[edit]

Behavioral methods involveregulating the timingor method of intercourse to prevent introduction of sperm into the female reproductive tract, either altogether or when an egg may be present.[91]If used perfectly the first-year failure rate may be around 3.4%; however, if used poorly first-year failure rates may approach 85%.[92]

Fertility awareness[edit]

Fertility awareness methodsinvolve determining the most fertile days of themenstrual cycleand avoiding unprotected intercourse.[91]Techniques for determining fertility include monitoringbasal body temperature,cervical secretions,or the day of the cycle.[91]They have typical first-year failure rates of 24%; perfect use first-year failure rates depend on which method is used and range from 0.4% to 5%.[23]The evidence on which these estimates are based, however, is poor as the majority of people in trials stop their use early.[91]Globally, they are used by about 3.6% of couples.[93]If based on both basal body temperature and another primary sign, the method is referred to as symptothermal. First-year failure rates of 20% overall and 0.4% for perfect use have been reported in clinical studies of the symptothermal method.[94][23]A number offertility trackingapps are available, as of 2016, but they are more commonly designed to assist those trying to get pregnant rather than prevent pregnancy.[95]

Withdrawal[edit]

Thewithdrawal method(also known as coitus interruptus) is the practice of ending intercourse ( "pulling out" ) before ejaculation.[96]The main risk of the withdrawal method is that the man may not perform the maneuver correctly or in a timely manner.[96]First-year failure rates vary from 4% with perfect usage to 22% with typical usage.[23]It is not considered birth control by some medical professionals.[29]

There is little data regarding the sperm content ofpre-ejaculatory fluid.[97]While some tentative research did not find sperm,[97]one trial found sperm present in 10 out of 27 volunteers.[98]The withdrawal method is used as birth control by about 3% of couples.[93]

Abstinence[edit]

Sexual abstinencemay be used as a form of birth control, meaning either not engaging in any type of sexual activity, or specifically not engaging in vaginal intercourse, while engaging in other forms of non-vaginal sex.[99][100]Complete sexual abstinence is 100% effective in preventing pregnancy.[101][102]However, among those who take apledge to abstainfrompremarital sex,as many as 88% who engage in sex, do so prior to marriage.[103]The choice to abstain from sex cannot protect against pregnancy as a result of rape, and public health efforts emphasizing abstinence to reduce unwanted pregnancy may have limited effectiveness, especially indeveloping countriesand amongdisadvantaged groups.[104][105]

Deliberatenon-penetrative sexwithout vaginal sex or deliberateoral sexwithout vaginal sex are also sometimes considered birth control.[99]While this generally avoids pregnancy, pregnancy can still occur withintercrural sexand other forms of penis-near-vagina sex (genital rubbing, and the penis exiting fromanal intercourse) where sperm can be deposited near the entrance to the vagina and can travel along the vagina's lubricating fluids.[106][107]

Abstinence-only sex educationdoes not reduceteenage pregnancy.[9][108]Teen pregnancy rates and STI rates are generally the same or higher in states where students are given abstinence-only education, as compared withcomprehensive sex education.[108]Some authorities recommend that those using abstinence as a primary method have backup methods available (such as condoms or emergency contraceptive pills).[109]

Lactation[edit]

Thelactational amenorrhea methodinvolves the use of a woman's naturalpostpartum infertilitywhich occurs after delivery and may be extended bybreastfeeding.[110]For a postpartum women to be infertile (protected from pregnancy), their periods have usually not yet returned (not menstruating), they are exclusively breastfeeding the infant, and the baby is younger than six months.[26]If breastfeeding is the infant's only source of nutrition and the baby is less than 6 months old, 93–99% of women are estimated to have protection from becoming pregnant in the first six months (0.75–7.5% failure rate).[111][112]The failure rate increases to 4–7% at one year and 13% at two years.[113]Feeding formula, pumping instead of nursing, the use of apacifier,and feeding solids all increase the chances of becoming pregnant while breastfeeding.[114]In those who are exclusively breastfeeding, about 10% begin having periods before three months and 20% before six months.[113]In those who are not breastfeeding, fertility may return as early as four weeks after delivery.[113]

Emergency[edit]

Emergency contraceptivemethods are medications (sometimes misleadingly referred to as "morning-after pills" )[115]or devices used after unprotected sexual intercourse with the hope of preventing pregnancy. Emergency contraceptives are often given to victims of rape.[10]They work primarily by preventing ovulation or fertilization.[2][116]They are unlikely to affect implantation, but this has not been completely excluded.[116]A number of options exist, includinghigh dose birth control pills,levonorgestrel,mifepristone,ulipristaland IUDs.[117]All methods have minimal side effects.[117]Providing emergency contraceptive pills to women in advance of sexual activity does not affect rates of sexually transmitted infections, condom use, pregnancy rates, or sexual risk-taking behavior.[118][119]In a UK study, when a three-month "bridge" supply of theprogestogen-only pillwas provided by a pharmacist along with emergency contraception after sexual activity, this intervention was shown to increase the likelihood that the person would begin to use an effective method of long-term contraception.[120][121]

Levonorgestrelpills, when used within 3 days, decrease the chance of pregnancy after a single episode of unprotected sex or condom failure by 70% (resulting in a pregnancy rate of 2.2%).[10]Ulipristal,when used within 5 days, decreases the chance of pregnancy by about 85% (pregnancy rate 1.4%) and is more effective than levonorgestrel.[10][117][122]Mifepristoneis also more effective than levonorgestrel, while copper IUDs are the most effective method.[117]IUDs can be inserted up to five days after intercourse and prevent about 99% of pregnancies after an episode of unprotected sex (pregnancy rate of 0.1 to 0.2%).[2][123]This makes them the most effective form of emergency contraceptive.[124]In those who areoverweightorobese,levonorgestrel is less effective and an IUD or ulipristal is recommended.[125]

Dual protection[edit]

Dual protection is the use of methods that prevent bothsexually transmitted infectionsand pregnancy.[126]This can be with condoms either alone or along with another birth control method or by the avoidance ofpenetrative sex.[127][128]

If pregnancy is a high concern, using two methods at the same time is reasonable.[127]For example, two forms of birth control are recommended in those taking the anti-acnedrugisotretinoinoranti-epileptic drugslikecarbamazepine,due to the high risk ofbirth defectsif taken during pregnancy.[129][130]

Effects[edit]

Health[edit]

Contraceptive use indeveloping countriesis estimated to have decreased the number ofmaternal deathsby 40% (about 270,000 deaths prevented in 2008) and could prevent 70% of deaths if the full demand for birth control were met.[19][20]These benefits are achieved by reducing the number of unplanned pregnancies that subsequently result in unsafe abortions and by preventing pregnancies in those at high risk.[19]

Birth control also improves child survival in the developing world by lengthening the time between pregnancies.[19]In this population, outcomes are worse when a mother gets pregnant within eighteen months of a previous delivery.[19][132]Delaying another pregnancy after amiscarriage,however, does not appear to alter risk and women are advised to attempt pregnancy in this situation whenever they are ready.[132]

Teenage pregnancies,especially among younger teens, are at greater risk of adverse outcomes includingearly birth,low birth weight,anddeath of the infant.[14]In 2012 in the United States 82% of pregnancies in those between the ages of 15 and 19 years old are unplanned.[72]Comprehensivesex educationand access to birth control are effective in decreasing pregnancy rates in this age group.[133]

Birth control methods, especiallyhormonal methods,can also have undesirable side effects. Intensity of side effects can range from minor to debilitating, and varies with individual experiences. These most commonly include change in menstruation regularity and flow, nausea, breast tenderness, headaches, weight gain, and mood changes (specifically an increase in depression and anxiety).[134][135]Additionally, hormonal contraception can contribute to bone mineral density loss, impaired glucose metabolism, increased risk of venous thromboembolism.[135][134]Comprehensive sex education and transparent discussion of birth control side effects and contraindications between healthcare provider and patient is imperative.[134]

Finances[edit]

In the developing world, birth control increases economic growth due to there being fewer dependent children and thus more women participating in or increased contribution to theworkforce– as they are usually the primarycaregiverfor children.[21]Women's earnings, assets,body mass index,and their children's schooling and body mass index all improve with greater access to birth control.[21]Family planning,via the use of modern birth control, is one of the mostcost-effectivehealth interventions.[136]For every dollar spent, the United Nations estimates that two to six dollars are saved.[18]These cost savings are related to preventing unplanned pregnancies and decreasing the spread of sexually transmitted illnesses.[136]While all methods are beneficial financially, the use of copper IUDs resulted in the greatest savings.[136]

The total medical cost for a pregnancy, delivery and care of a newborn in the United States is on average $21,000 for a vaginal delivery and $31,000 for acaesarean deliveryas of 2012.[137]In most other countries, the cost is less than half.[137]For a child born in 2011, an average US family will spend $235,000 over 17 years to raise them.[138]

Prevalence[edit]

6% 12% 18% 24% | 30% 36% 48% 60% | 66% 78% 86% No data |

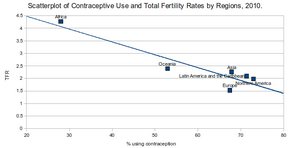

Globally, as of 2009, approximately 60% of those who are married and able to have children use birth control.[140]How frequently different methods are used varies widely between countries.[140]The most common method in the developed world is condoms and oral contraceptives, while in Africa it is oral contraceptives and in Latin America and Asia it is sterilization.[140]In the developing world overall, 35% of birth control is via female sterilization, 30% is via IUDs, 12% is via oral contraceptives, 11% is via condoms, and 4% is via male sterilization.[140]

While less used in the developed countries than the developing world, the number of women using IUDs as of 2007 was more than 180 million.[65]Avoiding sex when fertile is used by about 3.6% of women of childbearing age, with usage as high as 20% in areas of South America.[141]As of 2005, 12% of couples are using a male form of birth control (either condoms or a vasectomy) with higher rates in the developed world.[142]Usage of male forms of birth control has decreased between 1985 and 2009.[140]Contraceptive use among women inSub-Saharan Africahas risen from about 5% in 1991 to about 30% in 2006.[143]

As of 2012, 57% of women of childbearing age want to avoid pregnancy (867 of 1,520 million).[144]About 222 million women, however, were not able to access birth control, 53 million of whom were in sub-Saharan Africa and 97 million of whom were in Asia.[144]This results in 54 million unplanned pregnancies and nearly 80,000 maternal deaths a year.[140]Part of the reason that many women are without birth control is that many countries limit access due to religious or political reasons,[2]while another contributor is poverty.[145]Due to restrictive abortion laws in Sub-Saharan Africa, many women turn to unlicensed abortion providers forunintended pregnancy,resulting in about 2–4% obtainingunsafe abortionseach year.[145]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The EgyptianEbers Papyrusfrom 1550 BC and theKahun Papyrusfrom 1850 BC have within them some of the earliest documented descriptions of birth control: the use of honey,acacialeaves and lint to be placed in the vagina to block sperm.[146][147]Silphium,a species ofgiant fennelnative to north Africa, may have been used as birth control inancient Greeceand theancient Near East.[148][149]Due to its desirability, by the first century AD, it had become so rare that it was worth more than its weight in silver and, by late antiquity, it was fully extinct.[148]Most methods of birth control used in antiquity were probably ineffective.[150]

Theancient GreekphilosopherAristotle(c.384–322 BC) recommended applyingcedar oilto the womb before intercourse, a method which was probably only effective on occasion.[150]AHippocratictextOn the Nature of Womenrecommended that a woman drink a coppersaltdissolved in water, which it claimed would prevent pregnancy for a year.[150]This method was not only ineffective, but also dangerous, as the later medical writerSoranus of Ephesus(c.98–138 AD) pointed out.[150]Soranus attempted to list reliable methods of birth control based on rational principles.[150]He rejected the use of superstition and amulets and instead prescribed mechanical methods such as vaginal plugs and pessaries using wool as a base covered in oils or other gummy substances.[150]Many of Soranus's methods were probably also ineffective.[150]

In medieval Europe, any effort to halt pregnancy was deemed immoral by theCatholic Church,[146]although it is believed that women of the time still used a number of birth control measures, such ascoitus interruptusand insertinglilyroot andrueinto the vagina.[151]Women in the Middle Ages were also encouraged to tie weasel testicles around their thighs during sex to prevent pregnancy.[152]The oldest condoms discovered to date were recovered in the ruins ofDudley Castlein England, and are dated back to 1640.[152]They were made of animal gut, and were most likely used to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections during theEnglish Civil War.[152]Casanova,living in 18th-century Italy, described the use of a lambskin covering to prevent pregnancy; however, condoms only became widely available in the 20th century.[146]

Birth control movement[edit]

The birth control movement developed during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[153]TheMalthusian League,based on the ideas ofThomas Malthus,was established in 1877 in the United Kingdom to educate the public about the importance offamily planningand to advocate for getting rid of penalties for promoting birth control.[154]It was founded during the "Knowlton trial" ofAnnie BesantandCharles Bradlaugh,who were prosecuted for publishing on various methods of birth control.[155]

In the United States,Margaret Sangerand Otto Bobsein popularized the phrase "birth control" in 1914.[156][157]Sanger primarily advocated for birth control on the idea that it would prevent women from seeking unsafe abortions, but during her lifetime, she began to campaign for it on the grounds that it would reduce mental and physical defects.[158][159]She was mainly active in the United States but had gained an international reputation by the 1930s. At the time, under theComstock Law,distribution of birth control information was illegal. Shejumped bailin 1914 after her arrest for distributing birth control information and left the United States for the United Kingdom.[160]In the U.K., Sanger, influenced by Havelock Ellis, further developed her arguments for birth control. She believed women needed to enjoy sex without fearing a pregnancy. During her time abroad, Sanger also saw a more flexiblediaphragmin a Dutch clinic, which she thought was a better form of contraceptive.[159]Once Sanger returned to the United States, she established a short-lived birth-control clinic with the help of her sister, Ethel Bryne, based in the Brownville section ofBrooklyn,New York[161]in 1916. It was shut down after eleven days and resulted in her arrest.[162]The publicity surrounding the arrest, trial, and appeal sparked birth control activism across the United States.[163]Besides her sister, Sanger was helped in the movement by her first husband, William Sanger, who distributed copies of "Family Limitation." Sanger's second husband, James Noah H. Slee, would also later become involved in the movement, acting as its main funder.[159]Sanger also contributed to the funding of research into hormonal contraceptives in the 1950s.[164]She helped fund research John Rock, and biologist Gregory Pincus that resulted in the first hormonal contraceptive pill, later called Enovid.[165]The first human trials of the pill were done on patients in the Worcester State Psychiatric Hospital, after whichclinical testing was done in Puerto Ricobefore Enovid was approved for use in the U.S.. The people participating in these trials were not fully informed on the medical implications of the pill, and often had minimal to no other family planning options.[166][167]The newly approved birth control method was not made available to the participants after the trials, and contraceptives are still not widely accessible in Puerto Rico.[165]

The increased use of birth control was seen by some as a form of social decay.[168]A decrease of fertility was seen as a negative. Throughout the Progressive Era (1890–1920), there was an increase of voluntary associations aiding the contraceptive movement.[168]These organizations failed to enlist more than 100,000 women because the use of birth control was often compared to eugenics;[168]however, there were women seeking a community with like-minded women. The ideology that surrounded birth control started to gain traction during the Progressive Era due to voluntary associations establishing community. Birth control was unlike the Victorian Era because women wanted to manage their sexuality. The use of birth control was another form of self-interest women clung to. This was seen as women began to gravitate towards strong figures, like theGibson Girl.[169]

The first permanent birth-control clinic was established in Britain in 1921 byMarie Stopesworking with the Malthusian League.[170]The clinic, run by midwives and supported by visiting doctors,[171]offered women's birth-control advice and taught them the use of acervical cap.Her clinic made contraception acceptable during the 1920s by presenting it in scientific terms. In 1921, Sanger founded the American Birth Control League, which later became thePlanned ParenthoodFederation of America.[172]In 1924 the Society for the Provision of Birth Control Clinics was founded to campaign for municipal clinics; this led to the opening of a second clinic inGreengate, Salfordin 1926.[173]Throughout the 1920s, Stopes and otherfeministpioneers, includingDora RussellandStella Browne,played a major role in breaking downtaboosabout sex. In April 1930 the Birth Control Conference assembled 700 delegates and was successful in bringing birth control and abortion into the political sphere – three months later, theMinistry of Health,in the United Kingdom, allowed local authorities to give birth-control advice in welfare centres.[174]

The National Birth Control Association was founded in Britain in 1931, and became theFamily Planning Associationeight years later. The Association amalgamated several British birth control-focused groups into 'a central organisation' for administering and overseeing birth control in Britain. The group incorporated the Birth Control Investigation Committee, a collective of physicians and scientists that was founded to investigate scientific and medical aspects of contraception with 'neutrality and impartiality'.[175]Subsequently, the Association effected a series of'pure'and'applied'product and safety standards that manufacturers must meet to ensure their contraceptives could be prescribed as part of the Association's standard two-part-technique combining 'a rubber appliance to protect the mouth of the womb' with a 'chemical preparation capable of destroying... sperm'.[176]Between 1931 and 1959, the Association founded and funded a series of tests to assess chemical efficacy and safety and rubber quality.[177]These tests became the basis for the Association's Approved List of contraceptives, which was launched in 1937, and went on to become an annual publication that the expanding network of FPA clinics relied upon as a means to 'establish facts [about contraceptives] and to publish these facts as a basis on which a sound public and scientific opinion can be built'.[178]

In 1936, theUnited States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuitruled inUnited States v. One Package of Japanese Pessariesthat medically prescribing contraception to save a person's life or well-being was not illegal under theComstock Laws.Following this decision, theAmerican Medical AssociationCommittee on Contraception revoked its 1936 statement condemning birth control.[179]A national survey in 1937 showed 71 percent of the adult population supported the use of contraception.[180]By 1938, 374 birth control clinics were running in the United States despite their advertisement still being illegal.[181]First LadyEleanor Rooseveltpublicly supported birth control and family planning.[182]The restrictions on birth control in the Comstock laws were effectively rendered null and void bySupreme CourtdecisionsGriswold v. Connecticut(1965)[183]andEisenstadt v. Baird(1972).[184]In 1966,President Lyndon B. Johnsonstarted endorsing public funding for family planning services, and the Federal Government began subsidizing birth control services for low-income families.[185]The Affordable Care Act,passed into law on March 23, 2010, under PresidentBarack Obama,requires all plans in the Health Insurance Marketplace to cover contraceptive methods. These include barrier methods, hormonal methods, implanted devices, emergency contraceptives, and sterilization procedures.[186]

Modern methods[edit]

In 1909, Richard Richter developed the first intrauterine device made from silkworm gut, which was further developed and marketed in Germany byErnst Gräfenbergin the late 1920s.[187]In 1951, an Austrian-born American chemist, namedCarl DjerassiatSyntexin Mexico City made the hormones in progesterone pills using Mexican yams (Dioscorea mexicana).[188]Djerassi had chemically created the pill but was not equipped to distribute it to patients. Meanwhile,Gregory PincusandJohn Rockwith help from thePlanned Parenthood Federation of Americadeveloped the first birth control pills in the 1950s, such asmestranol/noretynodrel,which became publicly available in the 1960s through the Food and Drug Administration under the nameEnovid.[172][189]Medical abortionbecame an alternative to surgical abortion with the availability ofprostaglandin analogsin the 1970s andmifepristonein the 1980s.[190]

Society and culture[edit]

Legal positions[edit]

Human rights agreements require most governments to provide family planning and contraceptive information and services. These include the requirement to create a national plan for family planning services, remove laws that limit access to family planning, ensure that a wide variety of safe and effective birth control methods are available including emergency contraceptives, make sure there are appropriately trained healthcare providers and facilities at an affordable price, and create a process to review the programs implemented. If governments fail to do the above it may put them in breach of binding international treaty obligations.[191]

In the United States, the 1965 Supreme Court decisionGriswold v. Connecticutoverturned a state law prohibiting dissemination of contraception information based on a constitutional right to privacy for marital relationships. In 1972,Eisenstadt v. Bairdextended this right to privacy to single people.[192]

In 2010, the United Nations launched theEvery Woman Every Childmovement to assess the progress toward meeting women's contraceptive needs. The initiative has set a goal of increasing the number of users of modern birth control by 120 million women in the world's 69 poorest countries by 2020. Additionally, they aim to eradicate discrimination against girls and young women who seek contraceptives.[193]TheAmerican Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists(ACOG) recommended in 2014 that oral birth control pills should beover the counter medications.[194]

Since at least the 1870s, American religious, medical, legislative, and legal commentators have debated contraception laws. Ana Garner and Angela Michel have found that in these discussions men often attach reproductive rights to moral and political matters, as part of an ongoing attempt to regulate human bodies. In press coverage between 1873 and 2013 they found a divide between institutional ideology and real-life experiences of women.[195]

Religious views[edit]

Religions vary widely in their views of the ethics of birth control.[196]TheRoman Catholic Churchre-affirmed its teachings in1968that onlynatural family planningis permissible,[197]although large numbers of Catholics indeveloped countriesaccept and use modern methods of birth control.[198][199][200]The Greek Orthodox Church admits a possible exception to its traditional teaching forbidding the use of artificial contraception, if used within marriage for certain purposes, including the spacing of births.[201]AmongProtestants,there is a wide range of views from supporting none, such as in theQuiverfull movement,to allowing all methods of birth control.[202]Views in Judaism range from the stricterOrthodoxsect, which prohibits all methods of birth control, to the more relaxedReformsect, which allows most.[203]Hindusmay use both natural and modern contraceptives.[204]A commonBuddhistview is that preventing conception is acceptable, while intervening after conception has occurred is not.[205]InIslam,contraceptives are allowed if they do not threaten health, although their use is discouraged by some.[206]

World Contraception Day[edit]

September 26 is World Contraception Day, devoted to raising awareness and improving education about sexual and reproductive health, with a vision ofa world where every pregnancy is wanted.[207]It is supported by a group of governments and international NGOs, including theOffice of Population Affairs,the Asian Pacific Council on Contraception, Centro Latinamericano Salud y Mujer, the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health, theGerman Foundation for World Population,the International Federation of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology,International Planned Parenthood Federation,theMarie Stopes International,Population Services International,thePopulation Council,theUnited States Agency for International Development(USAID), andWomen Deliver.[207]

Misconceptions[edit]

There are a number ofcommon misconceptionsregarding sex and pregnancy.[208]Douchingafter sexual intercourse is not an effective form of birth control.[209]Additionally, it is associated with a number of health problems and thus is not recommended.[210]Women can become pregnant the first time they have sexual intercourse[211]and in anysexual position.[212]It is possible, although not very likely, to become pregnant during menstruation.[213]Contraceptive use, regardless of its duration and type, does not have a negative effect on the ability of women to conceive following termination of use and does not significantly delay fertility. Women who use oral contraceptives for a longer duration may have a slightly lower rate of pregnancy than do women using oral contraceptives for a shorter period of time, possibly due to fertility decreasing with age.[214]

Accessibility[edit]

Access to birth control may be affected by finances and the laws within a region or country.[215]In the United States African American, Hispanic, and young women are disproportionately affected by limited access to birth control, as a result of financial disparity.[216][217]For example, Hispanic and African American women often lack insurance coverage and are more often poor.[218]New immigrants in the United States are not offered preventive care such as birth control.[219]

In the United Kingdom contraception can be obtained free of charge via contraception clinics,sexual healthor GUM (genitourinary medicine) clinics, via some GP surgeries, some young people's services and pharmacies.[220][221]

In September 2021, France announced that women aged under 25 in France will be offered free contraception from 2022. It was elaborated that they "would not be charged for medical appointments, tests, or other medical procedures related to birth control" and that this would "cover hormonal contraception, biological tests that go with it, the prescription of contraception and all care related to this contraception".[222]

From August 2022 onwards contraception for women aged between 17 and 25 years will be free in theRepublic of Ireland.[223][224]

Public provisioning for contraception[edit]

In most parts of the world, the political attitude to contraception determines whether and how much state provisioning of contraceptive care occurs. In the United States, for example, the Republican party and the Democratic party have held opposite positions, contributing to continuous policy shifts over the years.[225][226]In the 2010s, policies, and attitudes to contraceptive care shifted abruptly between Obama's and Trump's administrations.[225]The Trump administration extensively overturned the efforts for contraceptive care, and reduced federal spending, compared to efforts and funding during the Obama administration.[225]

Advocacy[edit]

Free the Pill,a collaboration betweenAdvocates for YouthandIbis Reproductive Healthare working to bring birth control over-the-counter, covered by insurance with no age-restriction throughout the United States.[227][228][229]

Approval[edit]

On July 13, 2023 the first US daily oral nonprescription over-the-counter birth control pill was approved for manufacturer by theFDA.The pill, Opill is expected to be more effective in preventing unintended pregnancies than condoms are. Opill is expected to be available in 2024 but the price has yet to be set.Perrigo,a pharmaceutical company based in Dublin is the manufacturer.[230]

Research directions[edit]

Females[edit]

Improvements of existing birth control methods are needed, as around half of those who get pregnant unintentionally are using birth control at the time.[29]A number of alterations of existing contraceptive methods are being studied, including a better female condom, an improveddiaphragm,a patch containing only progestin, and a vaginal ring containing long-acting progesterone.[231]This vaginal ring appears to be effective for three or four months and is currently available in some areas of the world.[231]For women who rarely have sex, the taking of the hormonal birth controllevonorgestrelaround the time of sex looks promising.[232]

A number of methods to perform sterilization via the cervix are being studied. One involves puttingquinacrinein the uterus which causes scarring and infertility. While the procedure is inexpensive and does not require surgical skills, there are concerns regarding long-term side effects.[233]Another substance,polidocanol,which functions in the same manner is being looked at.[231]A device calledEssure,which expands when placed in the fallopian tubes and blocks them, was approved in the United States in 2002.[233]In 2016, ablack boxed warningregarding potentially serious side effects was added,[234][235]and in 2018, the device was discontinued.[236]

Males[edit]

Despite high levels of interest in male contraception,[237][238][239]progress been stymied by a lack of industry involvement. Most funding for male contraceptive research is derived from government or philanthropic sources.[240][241][242][243]

A number of novel contraceptive methods based on hormonal and non-hormonal mechanisms of action are in various stages ofresearch and development,up to and includingclinical trials,[244][245][246][247][248][249]including gels, pills, injectables, implants, wearables, and oral contraceptives.[250][251][252]

Recent avenues of research includeproteinsandgenesrequired for malefertility.For instance, theserine/threonine-protein kinase33 (STK33) is atestis-enrichedkinasethat is indispensable for male fertility in humans and mice. An inhibitor of this kinase,CDD-2807,has recently been identified and induced reversible maleinfertilitywithout measurabletoxicityin mice.[253]Such an inhibitor would be a potent male contraceptive if it passed safety and efficacy tests.

Animals[edit]

Neuteringor spaying, which involves removing some of the reproductive organs, is often carried out as a method of birth control in household pets. Manyanimal sheltersrequire these procedures as part of adoption agreements.[254]In large animals the surgery is known ascastration.[255]

Birth control is also being considered as an alternative to hunting as a means of controllingoverpopulation in wild animals.[256]Contraceptive vaccineshave been found to be effective in a number of different animal populations.[257][258]Kenyan goat herders fix a skirt, called anolor,to male goats to prevent them from impregnating female goats.[259]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"Definition of Birth control".MedicineNet.Archivedfrom the original on August 6, 2012.RetrievedAugust 9,2012.

- ^abcdefghiHanson SJ, Burke AE (2010)."Fertility control: contraception, sterilization, and abortion".In Hurt KJ, Guile MW, Bienstock JL, Fox HE, Wallach EE (eds.).The Johns Hopkins manual of gynecology and obstetrics(4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 382–395.ISBN978-1-60547-433-5.

- ^Oxford English Dictionary.Oxford University Press. 2012.

- ^World Health Organization (WHO)."Family planning".Health topics.World Health Organization (WHO).Archivedfrom the original on March 18, 2016.RetrievedMarch 28,2016.

- ^Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use(Fifth ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2015.ISBN978-92-4-154915-8.OCLC932048744.

- ^Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, et al. (July 2016)."U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016".MMWR. Recommendations and Reports.65(3): 1–103.doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1.PMID27467196.

- ^abcdefWorld Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2011).Family planning: A global handbook for providers: Evidence-based guidance developed through worldwide collaboration(PDF)(Rev. and Updated ed.). Geneva: WHO and Center for Communication Programs.ISBN978-0-9788563-7-3.Archived(PDF)from the original on September 21, 2013.

- ^Taliaferro LA, Sieving R, Brady SS, Bearinger LH (December 2011). "We have the evidence to enhance adolescent sexual and reproductive health—do we have the will?".Adolescent Medicine.22(3): 521–43, xii.PMID22423463.

- ^abChin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, Mercer SL, Chattopadhyay SK, Jacob V, et al. (March 2012)."The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: two systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services".American Journal of Preventive Medicine.42(3): 272–94.doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.006.PMID22341164.

- ^abcdGizzo S, Fanelli T, Di Gangi S, Saccardi C, Patrelli TS, Zambon A, et al. (October 2012). "Nowadays which emergency contraception? Comparison between past and present: latest news in terms of clinical efficacy, side effects and contraindications".Gynecological Endocrinology.28(10): 758–63.doi:10.3109/09513590.2012.662546.PMID22390259.S2CID39676240.

- ^Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use(2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004. p. 13.ISBN978-92-4-156284-3.Archivedfrom the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Willan A, Griffith L (June 2002)."Interventions to reduce unintended pregnancies among adolescents: systematic review of randomised controlled trials".BMJ.324(7351): 1426.doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1426.PMC115855.PMID12065267.

- ^Duffy K, Lynch DA, Santinelli J, Santelli J (December 2008)."Government support for abstinence-only-until-marriage education".Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics.84(6): 746–8.doi:10.1038/clpt.2008.188.PMID18923389.S2CID19499439.Archivedfrom the original on December 11, 2008.

- ^abcBlack AY, Fleming NA, Rome ES (April 2012). "Pregnancy in adolescents".Adolescent Medicine.23(1): 123–38, xi.PMID22764559.

- ^abRowan SP, Someshwar J, Murray P (April 2012). "Contraception for primary care providers".Adolescent Medicine.23(1): 95–110, x–xi.PMID22764557.

- ^abcdeWorld Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2011).Family planning: A global handbook for providers: Evidence-based guidance developed through worldwide collaboration(PDF)(Rev. and Updated ed.). Geneva: WHO and Center for Communication Programs. pp. 260–300.ISBN978-0-9788563-7-3.Archived(PDF)from the original on September 21, 2013.

- ^Singh S, Darroch JE (June 2012)."Costs and Benefits of Contraceptive Services: Estimates for 2012"(PDF).United Nations Population Fund:1.Archived(PDF)from the original on August 5, 2012.

- ^abCarr B, Gates MF, Mitchell A, Shah R (July 2012)."Giving women the power to plan their families".Lancet.380(9837): 80–82.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60905-2.PMID22784540.S2CID205966410.Archivedfrom the original on May 10, 2013.

- ^abcdefCleland J, Conde-Agudelo A, Peterson H, Ross J,Tsui A(July 2012). "Contraception and health".Lancet.380(9837): 149–156.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60609-6.PMID22784533.S2CID9982712.

- ^abAhmed S, Li Q, Liu L, Tsui AO (July 2012)."Maternal deaths averted by contraceptive use: an analysis of 172 countries".Lancet.380(9837): 111–125.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60478-4.PMID22784531.S2CID25724866.Archivedfrom the original on May 10, 2013.

- ^abcdCanning D, Schultz TP (July 2012)."The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning".Lancet.380(9837): 165–171.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60827-7.PMID22784535.S2CID39280999.Archivedfrom the original on June 2, 2013.

- ^Van Braeckel D, Temmerman M, Roelens K, Degomme O (July 2012)."Slowing population growth for wellbeing and development".Lancet.380(9837): 84–85.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60902-7.PMID22784542.S2CID10015998.Archivedfrom the original on May 10, 2013.

- ^abcdefghijTrussell J (May 2011)."Contraceptive failure in the United States".Contraception.83(5): 397–404.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021.PMC3638209.PMID21477680.

Trussell J (2011). "Contraceptive efficacy". In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates Jr W, Kowal D, Policar MS (eds.).Contraceptive technology(20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 779–863.ISBN978-1-59708-004-0.ISSN0091-9721.OCLC781956734. - ^"U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013: adapted from the World Health Organization selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2nd edition".MMWR. Recommendations and Reports.62(RR-05). Division Of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention Health Promotion, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1–60. June 2013.PMID23784109.Archivedfrom the original on July 10, 2013.

- ^Van der Wijden C, Manion C (October 2015)."Lactational amenorrhoea method for family planning".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2015(10): CD001329.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001329.pub2.PMC6823189.PMID26457821.

- ^abBlenning CE, Paladine H (December 2005). "An approach to the postpartum office visit".American Family Physician.72(12): 2491–2496.PMID16370405.

- ^Edlin G, Golanty E, Brown KM (2000).Essentials for health and wellness(2nd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett. p. 161.ISBN978-0-7637-0909-9.Archivedfrom the original on June 10, 2016.

- ^Edmonds DK, ed. (2012).Dewhurst's textbook of obstetrics & gynaecology(8th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 508.ISBN978-0-470-65457-6.Archivedfrom the original on May 3, 2016.

- ^abcdefghiCunningham FG, Stuart GS (2012). "Contraception and sterilization". In B, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, Halvorson LM, Bradshaw KD, Cunningham FG (eds.).Williams gynecology(2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 132–69.ISBN978-0-07-171672-7.

- ^Committee on Adolescence (October 2014)."Contraception for adolescents".Pediatrics.134(4): e1244-56.doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2299.PMC1070796.PMID25266430.

- ^Mansour D, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Inki P, Jensen JT (November 2011). "Fertility after discontinuation of contraception: a comprehensive review of the literature".Contraception.84(5): 465–77.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.04.002.PMID22018120.

- ^abMedical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use(PDF)(4th ed.). Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization. 2009. pp. 1–10.ISBN978-92-4-156388-8.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on July 9, 2012.

- ^Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Family and Community (2004).Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use(PDF)(2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. p. Chapter 31.ISBN978-92-4-156284-3.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on July 18, 2013.

- ^Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Steenland MW, Marchbanks PA (May 2013)."Physical examination prior to initiating hormonal contraception: a systematic review".Contraception.87(5): 650–4.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.010.PMID23121820.

- ^abcdWorld Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2011).Family planning: A global handbook for providers: Evidence-based guidance developed through worldwide collaboration(PDF)(Rev. and Updated ed.). Geneva: WHO and Center for Communication Programs. pp. 1–10.ISBN978-0-9788563-7-3.Archived(PDF)from the original on September 21, 2013.

- ^"American Academy of Family Physicians | Choosing Wisely".www.choosingwisely.org.February 24, 2015.RetrievedAugust 14,2018.

- ^Mackenzie J (December 6, 2013)."The male pill? Bring it on".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on May 21, 2014.RetrievedMay 20,2014.

- ^Ammer C (2009)."oral contraceptive".The encyclopedia of women's health(6th ed.). New York: Facts On File. pp. 312–15.ISBN978-0-8160-7407-5.

- ^Nelson A, Cwiak C (2011). "Combined oral contraceptives (COCs)". In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates Jr W, Kowal D, Policar MS (eds.).Contraceptive technology(20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 249–341 [257–58].ISBN978-1-59708-004-0.ISSN0091-9721.OCLC781956734.

- ^abHoffman BL (2011). "5 Second-Tier Contraceptive Methods—Very Effective".Williams gynecology(2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical.ISBN978-0-07-171672-7.

- ^abcdBrito MB, Nobre F, Vieira CS (April 2011)."Hormonal contraception and cardiovascular system".Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia.96(4): e81-9.doi:10.1590/S0066-782X2011005000022.PMID21359483.

- ^Stegeman BH, de Bastos M, Rosendaal FR, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Helmerhorst FM, Stijnen T, Dekkers OM (September 2013)."Different combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis: systematic review and network meta-analysis".BMJ.347:f5298.doi:10.1136/bmj.f5298.PMC3771677.PMID24030561.

- ^Kurver MJ, van der Wijden CL, Burgers J (October 4, 2012)."[Summary of the Dutch College of General Practitioners' practice guideline 'Contraception']".Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde(in Dutch).156(41): A5083.PMID23062257.[permanent dead link]

- ^Tosetto A, Iorio A, Marcucci M, Baglin T, Cushman M, Eichinger S, et al. (June 2012)."Predicting disease recurrence in patients with previous unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a proposed prediction score (DASH)".Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.10(6): 1019–25.doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04735.x.PMID22489957.S2CID27149654.

- ^Burrows LJ, Basha M, Goldstein AT (September 2012). "The effects of hormonal contraceptives on female sexuality: a review".The Journal of Sexual Medicine.9(9): 2213–23.doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02848.x.PMID22788250.

- ^abShulman LP (October 2011). "The state of hormonal contraception today: benefits and risks of hormonal contraceptives: combined estrogen and progestin contraceptives".American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.205(4 Suppl): S9-13.doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.057.PMID21961825.

- ^Havrilesky LJ, Moorman PG, Lowery WJ, Gierisch JM, Coeytaux RR, Urrutia RP, et al. (July 2013). "Oral contraceptive pills as primary prevention for ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis".Obstetrics and Gynecology.122(1): 139–47.doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318291c235.PMID23743450.S2CID31552437.

- ^Mantha S, Karp R, Raghavan V, Terrin N, Bauer KA, Zwicker JI (August 2012)."Assessing the risk of venous thromboembolic events in women taking progestin-only contraception: a meta-analysis".BMJ.345(aug07 2): e4944.doi:10.1136/bmj.e4944.PMC3413580.PMID22872710.

- ^Burke AE (October 2011). "The state of hormonal contraception today: benefits and risks of hormonal contraceptives: progestin-only contraceptives".American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.205(4 Suppl): S14-7.doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.033.PMID21961819.

- ^Rott H (August 2012). "Thrombotic risks of oral contraceptives".Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology.24(4): 235–40.doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e328355871d.PMID22729096.S2CID23938634.

- ^abNeinstein L (2008).Adolescent health care: a practical guide(5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 624.ISBN978-0-7817-9256-1.Archivedfrom the original on June 17, 2016.

- ^Chaudhuri SK (2007)."Barrier Contraceptives".Practice Of Fertility Control: A Comprehensive Manual(7th ed.). Elsevier India. p. 88.ISBN978-81-312-1150-2.Archivedfrom the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^abHamilton R (2012).Pharmacology for nursing care(8th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 799.ISBN978-1-4377-3582-6.Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2016.

- ^Facts for life(4th ed.). New York: United Nations Children's Fund. 2010. p. 141.ISBN978-92-806-4466-1.Archivedfrom the original on May 13, 2016.

- ^Pray WS (2005).Nonprescription product therapeutics(2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 414.ISBN978-0-7817-3498-1.Archivedfrom the original on April 30, 2016.

- ^Committee on Adolescence (November 2013)."Condom Use by Adolescents".Pediatrics.132(5): 973–981.doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2821.PMID28448257.

- ^Eberhard N (2010).Andrology Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction(3rd ed.). [S.l.]: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. p. 563.ISBN978-3-540-78355-8.Archivedfrom the original on May 10, 2016.

- ^Barbieri JF (2009).Yen and Jaffe's reproductive endocrinology: physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management(6th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 873.ISBN978-1-4160-4907-4.Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2016.

- ^"Preventing Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)".British Columbia Health Link.February 2017. Archived fromthe originalon July 27, 2020.RetrievedMarch 31,2018.

- ^Kuyoh MA, Toroitich-Ruto C, Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Gallo MF (January 2003). "Sponge versus diaphragm for contraception: a Cochrane review".Contraception.67(1): 15–8.doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00434-1.PMID12521652.

- ^Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use(4th ed.). Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization. 2009. p. 88.ISBN978-92-4-156388-8.Archivedfrom the original on May 15, 2016.

- ^Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, Secura GM (May 2012)."Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception".The New England Journal of Medicine.366(21): 1998–2007.doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110855.PMID22621627.S2CID16812353.

- ^Hanson SJ, Burke AE (March 28, 2012)."Fertility Control: Contraception, Sterilization, and Abortion".In Hurt KJ, Guile MW, Bienstock JL, Fox HE, Wallach EE (eds.).The Johns Hopkins manual of gynecology and obstetrics(4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 232.ISBN978-1-60547-433-5.Archivedfrom the original on May 12, 2016.

- ^abCommittee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (October 2012)."Committee opinion no. 539: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices".Obstetrics and Gynecology.120(4): 983–8.doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b7d.PMID22996129.S2CID35516759.

- ^abSperoff L, Darney PD (2010).A clinical guide for contraception(5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 242–43.ISBN978-1-60831-610-6.Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016.

- ^Black K, Lotke P, Buhling KJ, Zite NB (October 2012)."A review of barriers and myths preventing the more widespread use of intrauterine contraception in nulliparous women".The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care.17(5): 340–50.doi:10.3109/13625187.2012.700744.PMC4950459.PMID22834648.

- ^abcGabbe S (2012).Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 527.ISBN978-1-4557-3395-8.Archivedfrom the original on May 15, 2016.

- ^Steenland MW, Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Kapp N (November 2011)."Intrauterine contraceptive insertion postabortion: a systematic review".Contraception.84(5): 447–64.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.007.PMID22018119.

- ^Roe AH, Bartz D (January 2019)."Society of Family Planning clinical recommendations: contraception after surgical abortion".Contraception.99(1): 2–9.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.016.PMID30195718.

- ^Falcone T, Hurd WW, eds. (2007).Clinical reproductive medicine and surgery.Philadelphia: Mosby. p. 409.ISBN978-0-323-03309-1.Archivedfrom the original on June 17, 2016.

- ^Grimes DA (2007). "Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)". In Hatcher RA, Nelson TJ, Guest F, Kowal D (eds.).Contraceptive Technology(19th ed.).

- ^abcMarnach ML, Long ME, Casey PM (March 2013)."Current issues in contraception".Mayo Clinic Proceedings.88(3): 295–9.doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.01.007.PMID23489454.

- ^"Popularity Disparity: Attitudes About the IUD in Europe and the United States".Guttmacher Policy Review. 2007.Archivedfrom the original on March 7, 2010.RetrievedApril 27,2010.

- ^Cramer DW (February 2012)."The epidemiology of endometrial and ovarian cancer".Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America.26(1): 1–12.doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2011.10.009.PMC3259524.PMID22244658.

- ^Adams CE, Wald M (August 2009). "Risks and complications of vasectomy".The Urologic Clinics of North America.36(3): 331–6.doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2009.05.009.PMID19643235.

- ^Hillard PA (2008).The 5-minute obstetrics and gynecology consult.Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 265.ISBN978-0-7817-6942-6.Archivedfrom the original on June 11, 2016.

- ^"Vasectomy Guideline – American Urological Association".www.auanet.org.RetrievedOctober 26,2021.

- ^Hillard PA (2008).The 5-minute obstetrics and gynecology consult.Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 549.ISBN978-0-7817-6942-6.Archivedfrom the original on May 5, 2016.

- ^Lee Goldman, Andrew I. Schafer, eds. (2020). "Contraception".Goldman-Cecil medicine(26th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 1568–1575.ISBN978-0-323-53266-2.OCLC1118693594.

- ^Fahim, M. S., et al. "Heat in male contraception (hot water 60°C, infrared, microwave, and ultrasound)." Contraception 11.5 (1975): 549–562.

- ^Fahim, M. S., et al. "Ultrasound as a new method of male contraception." Fertility and sterility 28.8 (1977): 823–831.

- ^Fahim, M. S., Z. Fahim, and F. Azzazi. "Effect of ultrasound on testicular electrolytes (sodium and potassium)." Archives of andrology 1.2 (1978): 179–184.

- ^Lonidamine analogues for fertility management, WO2011005759A3 WIPO (PCT), Ingrid Gunda GeorgeJoseph S. TashRamappa ChakrsaliSudhakar R. JakkarajJames P. Calvet

- ^United States Patent US3934015A, Oral male antifertility method and compositions

- ^Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, Peterson HB (June 1999). "Poststerilization regret: findings from the United States Collaborative Review of Sterilization".Obstetrics and Gynecology.93(6): 889–895.doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00539-0.PMID10362150.S2CID38389864.

- ^Hatcher R (2008).Contraceptive technology(19th ed.). New York: Ardent Media. p. 390.ISBN978-1-59708-001-9.Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2016.

- ^Moore DS (2010).The basic practice of statistics(5th ed.). New York: Freeman. p. 25.ISBN978-1-4292-2426-0.Archivedfrom the original on April 27, 2016.

- ^abcDeffieux X, Morin Surroca M, Faivre E, Pages F, Fernandez H, Gervaise A (May 2011). "Tubal anastomosis after tubal sterilization: a review".Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics.283(5): 1149–58.doi:10.1007/s00404-011-1858-1.PMID21331539.S2CID28359350.

- ^abShridharani A, Sandlow JI (November 2010). "Vasectomy reversal versus IVF with sperm retrieval: which is better?".Current Opinion in Urology.20(6): 503–9.doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b35.PMID20852426.S2CID42105503.

- ^Nagler HM, Jung H (August 2009). "Factors predicting successful microsurgical vasectomy reversal".The Urologic Clinics of North America.36(3): 383–90.doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2009.05.010.PMID19643240.

- ^abcdGrimes DA, Gallo MF, Grigorieva V, Nanda K, Schulz KF (October 2004)."Fertility awareness-based methods for contraception".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2012(4): CD004860.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004860.pub2.PMC8855505.PMID15495128.

- ^Lawrence R (2010).Breastfeeding: a guide for the medical professional(7th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 673.ISBN978-1-4377-0788-5.

- ^abFreundl G, Sivin I, Batár I (April 2010). "State-of-the-art of non-hormonal methods of contraception: IV. Natural family planning".The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care.15(2): 113–23.doi:10.3109/13625180903545302.PMID20141492.S2CID207523506.

- ^Jennings VH, Burke AE (November 1, 2011). "Fertility awareness-based methods". In Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates Jr W, Kowal D, Policar MS (eds.).Contraceptive technology(20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 417–34.ISBN978-1-59708-004-0.ISSN0091-9721.OCLC781956734.

- ^Mangone ER, Lebrun V, Muessig KE (January 2016)."Mobile Phone Apps for the Prevention of Unintended Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Content Analysis".JMIR mHealth and uHealth.4(1): e6.doi:10.2196/mhealth.4846.PMC4738182.PMID26787311.

- ^abMedical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use(PDF)(4th ed.). Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization. 2009. pp. 91–100.ISBN978-92-4-156388-8.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on July 9, 2012.

- ^abJones RK, Fennell J, Higgins JA, Blanchard K (June 2009). "Better than nothing or savvy risk-reduction practice? The importance of withdrawal".Contraception.79(6): 407–10.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.12.008.PMID19442773.

- ^Killick SR, Leary C, Trussell J, Guthrie KA (March 2011)."Sperm content of pre-ejaculatory fluid".Human Fertility.14(1): 48–52.doi:10.3109/14647273.2010.520798.PMC3564677.PMID21155689.

- ^ab"Abstinence".Planned Parenthood.2009.Archivedfrom the original on September 10, 2009.RetrievedSeptember 9,2009.

- ^Murthy AS, Harwood B (2007). "Contraception Update".Primary Care in Obstetrics and Gynecology(2nd ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 241–264.doi:10.1007/978-0-387-32328-2_12.ISBN978-0-387-32327-5.

- ^Alters S, Schiff W (October 5, 2009).Essential Concepts for Healthy Living.Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 116.ISBN978-0-7637-5641-3.RetrievedDecember 30,2017.

- ^Greenberg JS, Bruess CE, Oswalt SB (2016).Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality.Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 191.ISBN978-1-4496-9801-0.RetrievedDecember 30,2017.

- ^Fortenberry JD (April 2005). "The limits of abstinence-only in preventing sexually transmitted infections".The Journal of Adolescent Health.36(4): 269–70.doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.001.PMID15780781.

- ^Best K (2005)."Nonconsensual Sex Undermines Sexual Health".Network.23(4). Archived fromthe originalon February 18, 2009.

- ^Francis L (2017).The Oxford Handbook of Reproductive Ethics.Oxford University Press.p. 329.ISBN978-0-19-998187-8.RetrievedDecember 30,2017.

- ^Thomas RM (2009).Sex and the American teenager seeing through the myths and confronting the issues.Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education. p. 81.ISBN978-1-60709-018-2.

- ^Edlin G (2012).Health & Wellness.Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 213.ISBN978-1-4496-3647-0.

- ^abSantelli JS, Kantor LM, Grilo SA, Speizer IS, Lindberg LD, Heitel J, et al. (September 2017)."Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: An Updated Review of U.S. Policies and Programs and Their Impact".The Journal of Adolescent Health.61(3): 273–280.doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.031.hdl:1805/15683.PMID28842065.

- ^Kowal D (2007)."Abstinence and the Range of Sexual Expression".In Hatcher RA, et al. (eds.).Contraceptive Technology(19th rev. ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp.81–86.ISBN978-0-9664902-0-6.

- ^Blackburn ST (2007).Maternal, fetal, & neonatal physiology: a clinical perspective(3rd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier. p. 157.ISBN978-1-4160-2944-1.Archivedfrom the original on May 12, 2016.

- ^"WHO 10 facts on breastfeeding".World Health Organization.April 2005. Archived fromthe originalon June 23, 2013.

- ^Van der Wijden C, Manion C (October 2015)."Lactational amenorrhoea method for family planning".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2015(10): CD001329.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001329.pub2.PMC6823189.PMID26457821.

- ^abcFritz M (2012).Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1007–08.ISBN978-1-4511-4847-3.Archivedfrom the original on June 3, 2016.

- ^Swisher J, Lauwers A (October 25, 2010).Counseling the nursing mother a lactation consultant's guide(5th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 465–66.ISBN978-1-4496-1948-0.Archivedfrom the original on June 16, 2016.

- ^Office of Population Research, Association of Reproductive Health Professionals (July 31, 2013)."What is the difference between emergency contraception, the 'morning after pill', and the 'day after pill'?".Princeton: Princeton University.Archivedfrom the original on September 23, 2013.RetrievedSeptember 7,2013.

- ^abLeung VW, Levine M, Soon JA (February 2010). "Mechanisms of action of hormonal emergency contraceptives".Pharmacotherapy.30(2): 158–68.doi:10.1592/phco.30.2.158.PMID20099990.S2CID41337748.

The evidence strongly supports disruption of ovulation as a mechanism of action. The data suggest that emergency contraceptives are unlikely to act by interfering with implantation

- ^abcdShen J, Che Y, Showell E, Chen K, Cheng L, et al. (Cochrane Fertility Regulation Group) (January 2019)."Interventions for emergency contraception".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.1(1): CD001324.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001324.pub6.PMC7055045.PMID30661244.

- ^Kripke C (September 2007). "Advance provision for emergency oral contraception".American Family Physician.76(5): 654.PMID17894132.

- ^Shrader SP, Hall LN, Ragucci KR, Rafie S (September 2011). "Updates in hormonal emergency contraception".Pharmacotherapy.31(9): 887–95.doi:10.1592/phco.31.9.887.PMID21923590.S2CID33900390.

- ^Beeston A (January 27, 2022)."Pharmacists gave the POP with emergency contraception".NIHR Evidence.doi:10.3310/alert_48882.RetrievedMay 31,2024.

- ^Cameron ST, Glasier A, McDaid L, Radley A, Patterson S, Baraitser P, Stephenson J, Gilson R, Battison C, Cowle K, Vadiveloo T, Johnstone A, Morelli A, Goulao B, Forrest M (May 5, 2021)."Provision of the progestogen-only pill by community pharmacies as bridging contraception for women receiving emergency contraception: the Bridge-it RCT".Health Technology Assessment.25(27): 1–92.doi:10.3310/hta25270.hdl:2164/16696.ISSN2046-4924.

- ^Richardson AR, Maltz FN (January 2012). "Ulipristal acetate: review of the efficacy and safety of a newly approved agent for emergency contraception".Clinical Therapeutics.34(1): 24–36.doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.012.PMID22154199.

- ^"Update on Emergency Contraception".Association of Reproductive Health Professionals. March 2011.Archivedfrom the original on May 11, 2013.RetrievedMay 20,2013.

- ^Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J (July 2012)."The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience".Human Reproduction.27(7): 1994–2000.doi:10.1093/humrep/des140.PMC3619968.PMID22570193.

- ^Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, Scherrer B, Mathe H, Levy D, et al. (October 2011). "Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel".Contraception.84(4): 363–7.doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.PMID21920190.

- ^"Dual protection against unwanted pregnancy and HIV / STDs".Sexual Health Exchange(3): 8. 1998.PMID12294688.

- ^abCates W, Steiner MJ (March 2002)."Dual protection against unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections: what is the best contraceptive approach?".Sexually Transmitted Diseases.29(3): 168–74.doi:10.1097/00007435-200203000-00007.PMID11875378.S2CID42792667.

- ^Farber NA, Farber NA (May 2000)."Statement on Dual Protection against Unwanted Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Infections, including HIV".Terapevticheskii Arkhiv.53(10). International Planned Parenthood Federation: 135–140.Archivedfrom the original on April 10, 2016.