Uí Fidgenti

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(September 2013) |

Uí Fidgenti | |

|---|---|

| 4th century–fragmented late 13th century | |

| Capital | Brugh Ríogh(Dún Eochair Maigue) |

| Common languages | Old Irish,Middle Irish,Classical Gaelic,Latin |

| Religion | Gaelic polytheism, Christianity |

| Government | Clan / Corporate |

| Elected Chief | |

• fl. circa 379 AD | Fiachu Fidgenid |

• | independent chiefs |

| Historical era | fl.Late Antiquity |

• Established | 4th century |

• Disestablished | fragmented late 13th century |

| ISO 3166 code | IE |

TheUí Fidgenti,Fidgeinti,Fidgheinte,Fidugeinte,Fidgente,orFidgeinte(/iːˈfiːjɛnti/or/ˈfiːjɛntə/;[notes 1]"descendants of, or of the tribe of, Fidgenti" ) were an early kingdom of northernMunsterin Ireland, situated mostly in modernCounty Limerick,but extending intoCounty ClareandCounty Tipperary,and possibly evenCounty KerryandCounty Cork,at maximum extents, which varied over time. They flourished from about 377 AD (assumption of power of Fidgheinte) to 977 (death ofDonovan), although they continued to devolve for another three hundred years. They have been given various origins among both the early or proto-Eóganachtaand among theDáirineby different scholars working in a number of traditions, with no agreement ever reached or appearing reachable.

Clans

[edit]Genealogies deriving from the Uí Fidgenti include O'Billry, O’Bruadair (Brouder), O'Cennfhaelaidh (Kenneally/Kenealy), Clerkin, Collins (Cuilen), O'Connell, O'Dea,O'Donovan,Flannery, O'Heffernans, Kenealyes, Mac Eneiry, O'Quin, and Tracy.[1]Whether a surname is distinguished with an "O'" is irrelevant, as all the old Irish families derive from their "Ui" prefix designation; the use of the "O" was discouraged during the era of the Penal Laws, and came back into vogue in connection with the rise of Irish nationalism after the 1840s.

Closely related to the Uí Fidgenti were theUí Liatháin,who claimed descent from the same 4th century AD dynast,Dáire Cerbba(Maine Munchaín), and who in the earliest sources, such asThe Expulsion of the Déisi(incidentally),[2]are mentioned together with them.

The Uí Fidgenti descend from Fiachu Fidgenti, the second son of Dáire Cerbba, whom, it is believed, became the senior line of the Milesian race upon the death of Crimhthann in 379 AD Fiacha himself, however, never became King of Munster, for he was killed by his rival, Aengus Tireach, great grandson of Cormac Cas, in a battle fought at Clidhna, near Glandore Harbor.[3]As noted in the Book of Lecan, Fiacha received the designation because he constructed a wooden horse at the fair of Aenach Cholmain.

Ultimately, six hundred years after the time of Fiacha, the territories of the Uí Fidgenti divided into two principal factions orsepts,theUí Chairpre ÁebdaandUí Chonaill Gabra.[4][5][6][7]The latter were more often the stronger power.[5]By 1169, the Uí Chairpre had further divided into the Uí Chairpre and the Uí Dhonnabháin,[8]though comparing the genealogies set forth in Rawlin and the Book of Munster, the lines diverged with Cenn Faelad, four generations before Donovan (died 974), reflecting that specific family's alliance with the Danes of Limerick and Waterford.

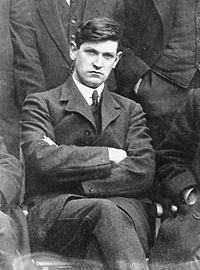

Modern descendants of Daire Cerbba include theO'Connells of Derrynane,[9][10]Daniel Charles, Count O'Connellhaving explicitly declared this to the heralds ofLouis XVI of France.Also wasMichael Collins,descending from the Ó Coileáin of Uí Chonaill Gabra,[11][12]once the most powerfulseptof the Uí Fidgenti.

Size and extents

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(October 2010) |

A variety of sources show that Uí Fidgenti was the most prominent of the non-(classical)-Eóganacht overkingdoms of medieval Munster, once the formerly powerfulCorcu Loígdeand distantOsraigeare excluded as non-participating.[13]By circa 950, the territory of the Ui Fidgheinte were divided primarily between the two most powerful septs, the Ui Cairbre and the Ui Coilean. The Ui Cairbre Aobhdha (of which O’Donovan were chief), lay along the Maigue basin in Coshmagh and Kenry (Caenraighe) and covered the deanery of Adare, and at one point extended past Kilmallock to Ardpartrick and Doneraile. The tribes of Ui Chonail Gabhra extended to a western district, along the Deel and Slieve Luachra, now the baronies of Upper and Lower Connello. Other septs within the Ui Fidgheinte were long associated with other Limerick locations; a branch of the Fir Tamnaige gave its name to Mahoonagh, or Tawnagh.[14]Feenagh is the only geographical trace extant today of ancient Ui-Fidhgeinte. Though the changes in the name of Ui-Fidhgeinte down to the modern Feenagh seem strange, they are quite natural when one takes into account the gradual change from the Irish to the English tongue with a totally different method of spelling and pronunciation and the omission of the "Ui" which was unintelligible to those acquainted only with the latter language. During 1750 to 1900, Fidgeinte had become FOUGHANOUGH or FEOHONAGH,[15]and finally FEENAGH—a name now confined to a single parish southeast of Newcastle in County Limerick.[16]

Saint Patrick

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(December 2009) |

Vita tripartita Sancti Patricii[17]

Saint Senan

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(October 2010) |

Uí Fiachrach Aidhne

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(December 2009) |

The Annals first note the Uí Fidgenti in 645 (649) as allies of the celebrated king ofConnacht,Guaire Aidne mac Colmáin,at theBattle of Carn Conaill.His dynasty, theUí Fiachrach Aidhne,controlled much of the territory to the immediate north of the Uí Fidgenti. Byrne argues[18]the two kingdoms were in rivalry for control over several smaller tuaths, but other evidence suggests they were allied.[19]In the 8th century Lament of Crede, daughter of Guaire, the Ui Fidghente are noted as opponents of her father at the battle of Aine in 667.

Sites and finds

[edit]

Dún Eochair(Maighe) was the great capital of the Uí Fidgenti,[5][20]described byGeoffrey Keatingas having been one of the two great seats of the Dáirine and the legendaryCú Roí mac Dáire.[21]The earthworks remain and the fortress can be found next to the modern town ofBruree,[22]on theRiver Maigue.The name means "Fortress on the Brink of the Maigue", and the name of the town is anglicised from Brugh Righ, meaning "Fort (Brugh) of Kings (Righ)". The town still has a sectionLissoleem,meaning, literally, the ringfort ( "lis" ) of Oilioll Olum (alternative spellingAilill Aulom),[22][23]who died 234 AD, entombed at Duntryleague, and who was the great great great grandfather of Fiachu Fidhgeinte, and from whom many of the Eoghanachta tribes descend.

To the south of Brugh Riogh can be foundCnoc Samhna( "Hill ofSamhain"),[24]also known asArd na Ríoghraidhe( "Height of the Kingfolk" ). Associated withMongfind,[25]this may have been the Uí Fidgenti inauguration site.

TheArdagh Chalicewas discovered in Uí Fidgenti territory, at Reerasta Rath in 1868.[26][27]

Eóganachta relationship

[edit]The Uí Fidgenti are credited with having a unique relationship with the Eóganachta kings atCashel.Five generations before Fiacha, Oilioll Olum (died 234 AD) is credited with dividing Munster into two parts and between two of his sons, and enjoined that their descendants should succeed to the governance of the province in alternate succession; this injunction was complied with until the time of Brian Boru, who is credited with slaying Donovan of the Ui Fidgheinte in 977.[28]

The Ui Fidgheinte were not subject to the Eóganachta kings at Cashel, and did not pay tribute. The Book of Rights noted that the stipends of the King of Cashel to the kings of his territory included, to the King of Ui Chonaill: ten steeds, shields, horns; and, to the King of BrughRigh (now Bruree): seven steeds, horns, swords and seven serving youths and seven bondmen. It also noted that the word of the King of Ui Chonail to the Kings of Cashel was sufficient, and no hostages need be exchanged as consideration for an agreement. A passage inThe Expulsion of the Déisi[29]names the Uí Fidgenti, including the Uí Liatháin, among the Three Eóganachta of Munster, the others being theEóganacht Locha Léinand theEóganacht Raithlind.[30]All three were of sufficient military and political standing to exchange hostages with the Kings at Cashel, instead of them being required as would be demanded from a subjugated opponent.[31]

Disintegration

[edit]The disintegration of the Uí Fidgenti commenced in 1178, whenDomnall Mor O'Briencaused the Uí Chonaill and Uí Chairpri to flee as far as Eóganacht Locha Léin and others intoCounty Kerry(AI). The O'Collins, the most powerful sept, would follow many of the O'Donovans some decades later,[32]but one or two smaller septs within the Ui Fidghente, notably the MacEnirys,[32]would remain in County Limerick for several centuries more as lords under the newEarls of Desmond.Important families which did not survive intact from the war waged by theO'Briens,and the subsequent incursion of theFitzGeralds,wereKenneally,Flannery, Tracey, Clerkin, and Ring. These septs scattered all over Munster.

The recurring conflict with the O'Briens had its most infamous event more than two centuries before, whenDonnubán mac Cathail,progenitor of the O'Donovans, formed an anti-Dalcassianalliance with two other leaders, his father-in-lawIvar of Limerick,theDanishking ofLimerick,andMáel Muad mac Brain,King of Munster.The result of this was the death of the elder brother ofBrian Bóruma,Mahon,Mathgamain mac Cennétig,for his frequent attacks on Ui Fidghente. His death resulted in Brian Boru's subsequent revenge by defeating all three members of the alliance.[33]In the 10th century, the territory of the Ui Fidghente bordered those of Mahon (in Cashel) and of Brian Boru (in Thomond), and territorial conflicts were not uncommon.

The Danish connection of the Ui Fidghente was also a considerable factor in the decrease of their power. The Ui Fidghenete had allied with the Ui Imhar five generations before Donovan was slain in 977, and the O'Donovans continued to carry Danish-dominated names well past the death of Amlaíb (Olaf) Ua Donnubáinof in 1201. Having allied with the losing side of the Danish / Irish conflicts in the late 10th century, the O'Donovans of Ui Chairbre saw their influence wane during the next two centuries while they tried to stem the tide against more powerful forces.

The core of the Uí Chonaill Gabra, under the O'Collins, remained a powerful force in Munster for some period of time. TheAnnals of Inisfallennote that in 1177 there was "An expedition by Domnall Ua Donnchada (Donnell O'Donoghue) and Cuilén Ua Cuiléin (Colin O'Collins) against Machaire, and they took away many cows. Peace was afterwards made by the son of Mac Carthaig (MacCarthy) and by the Uí Briain (O'Briens)".[34]This suggests the Uí Chonaill Gabra commanded one of the largest forces in Munster at this time and that it was not until after sustained attacks from the FitzGeralds that they were forced to retire to Cork in the mid 13th century. The same Cuiléin Ua Cuiléin and many of the nobles of Uí Chonaill Gabra were slain in a battle with Domnall Mac Carthaig in 1189,[35]an unfortunate event which contributed to their weak resistance against the invadingCambro-Normans.Shortly thereafter, in 1201, Domnall Mac Carthaig brought a hosting into Uí Chairpri, where he was slain; one year later, the last king of Uí Chairpre mentioned in the annalsAmlaíb Ua Donnubáin,was slain byWilliam de Burghand the sons of Domnall Mór Ua Briain in the year 1201 (AI). It is clear that the chiefs and territories of what were formerly the Ui-Fidghente (i.e. the Uí Chonaill Gabra and the Uí Chairpri) were under pressure after 1178, indicating they were still in their historical territory after the 1169 invasion of foreigners, and were caught in the crossfire between the MacCarthaigs, the O'Brians and the English foreigners. By the end of the 12th century, the Ui Fidghente territory was under extreme pressure from all sides, as the MacCarthaigs, O'Brians and the English foreigners (Fitzgerald, Fitzmaurice, DeBurgo) looked to the south and west to expand against the remnants of the Ui Fidghente, the Uí Chonaill Gabra and the Ui Chairpre, who were without formidable allies.

County Clare

[edit]Because of the later dominance of County Clare by the Dál gCais, the Uí Fidgenti septs there have proven difficult to trace and identify. A powerful branch of the Uí Chonaill Gabra known as the Uí Chormaic preserved their identity, from whom descend the O'Hehirs, but it is believed that other families were later wrongly classified as Dalcassian.

Corcu Loígde

[edit]Evidence may or may not exist for long-term exchange between the Uí Fidgenti andCorcu Loígde.This appears to be a relic of the pre-Eóganachta political configuration of Munster, and may support the theory of (some) Uí Fidgenti origins among the Dáirine as cousins of the Corcu Loígde. There are a number of historical septs who may have their origins with one or the other, evident in collections of pedigrees as early as those found in Rawlinson B 502,[36]dating from 550 to 1130,[37]and as late as those collected byJohn O'Hartin the 19th century.[32]

An earlyO'Learyfamily are given an Uí Fidgenti (Uí Chonaill Gabra) pedigree,[38]but the Munster sept as a whole are generally regarded to belong to the Corcu Loígde.

It is worth noting thatMichael Collins (Irish leader)was descended from the Ó Coileáins ofUí Chonaill Gabra.[39]Both the Ui Chonaill and the Ui Donnobhans were tribes within the Ui-Fidghente.

Contents

[edit]- AI635.1 The battle of Cúil Óchtair between the UÍ Fhidgeinte and the Araid.

- AI649.2 Death of Crunnmael son of Aed, king of Uí Fhidgeinte.

- AI683.1 Kl. Death of Donennach, king of Uí Fhidgeinte, and the mortality of the children. [AU —; AU 683, 684].

- AI732.1 Kl. Death of Dub Indrecht son of Erc., king of Uí Fhidgeinte.

- AI751.1 Kl. Death of Dub dá Bairenn son of Aed Rón, king of Uí Fhidgeinte.

- AI762.2 Death of Flann son of Erc, king of Uí Fhidgeinte.

- AI766.2 A defeat [was inflicted] by the Uí Fhidgeinte and by the Araid Cliach on Mael Dúin, son of Aed, in Brega, i.e. Énboth Breg.

- AI774.4 Death of Cenn Faelad, king of Uí Fhidgeinte, and of Rechtabra, king of Corcu Bascinn.

- AI786.2 Death of Scandlán son of Flann son of Erc, king of Uí Fhidgeinte.

- AI834.8 Dúnadach son of Scannlán, king of Uí Fhidgeinte, won a battle against the heathens, in which many fell.

- AI835.9 Death of Dúnadach son of Scannlán, king of Uí Fhidgente.

- AI846.5 Niall son of Cenn Faelad, king of Uí Fhidgente, dies.

- AI860.2 Aed son of Dub dá Bairenn, king of Uí Fhidgeinte, dies.

- AI846.5 Niall son of Cenn Faelad, king of Uí Fhidgente, dies.

- AI906.4 Ciarmac, king of Uí Fhidgente, dies.

- AI962.4 Death of Scandlán grandson of Riacán, king of Uí Fhidgeinte.

- AI972.3 The capture of Mathgamain son of Cennétig, king of Caisel. He was treacherously seized by Donnuban and handed over to the son of Bran in violation of the guarantee and despite the interdiction of the elders of Mumu, and he was put to death by Bran's son.

- AI974.0 Death of Dhonnabhan mac Cathail, tigherna Ua Fidhgeinte.

- AI977.3 A raid byBrian, son of Cennétig,on Uí Fhidgeinte, and he made a slaughter offoreignerstherein.

- AI982.4 Uainide son of Dhonnabhán, king of Uí Chairpri, died.

- AI989.4 Congal son of Anrudán, king of Corcu Duibne, dies.

- AI1177.3 Great warfare this year between Tuadmumu (Thomond) and Desmumu (Munster), and from Luimnech to Corcach and from Clár Doire Mór to Cnoc Brénainn was laid waste, both church and lay property. And the Uí Meic Caille and the Uí Liatháin came into the west of Ireland, and the Eóganacht Locha Léin came as far as Férdruim in Uí Echach, the Ciarraige Luachra into Tuadmumu, and the Uí Chonaill and Uí Chairpri as far as Eóganacht Locha Léin.

- MCB1177.2 A great war broke out between Domhnall Mór Ó Briain and Diarmaid Mór Mac Carthaigh, and they laid waste from Limerick to Cork, and from Clár Doire Mhóir and Waterford to Cnoc Bréanainn, both church and lay property. The Uí Mac Caille fled southwards across the Lee into Uí Eachach, the Eóghanacht Locha Léin fled to Féardhruim in Uí Eachach, the Ciarraighe Luahra into Thomond, the Uí Chairbre, the Uí Chonaill, and the Uí Dhonnabháin into Eóghanacht Locha Léin, and to the country around Mangarta.

Pedigree

[edit]Based primarily onRawlinson B 502:[40]

Dáire Cerbba/Maine Munchaín | |_______________________________________________________________________________ | | | | | | | | | | FidachUí LiatháinUí Fidgenti Uí DedaidUí Duach Argetrois | |__________________________ | | | | Crimthann mac FidaigMongfind=Eochaid Mugmedón=Cairenn | | | | ConnachtaUí Néill

See also

[edit]- Pre-Norman invasion Irish Celtic kinship groups,from whom many of the modern Irish surnames came from

Notes

[edit]- ^In the pronunciation, the -d- is silent, and the -g- becomes a glide, producing what might be anglicizedFeeyentiorFeeyenta.

References

[edit]- ^Book of Munster

- ^ed. Meyer 1901

- ^Appendix to the Annals of the Four Masters edited by John O'Donovan, page 2434

- ^O'Donovan 1856

- ^abcBegley

- ^Mac Spealáin 1960

- ^Mac Spealáin 2004

- ^MacCarthaigs Book, 1177.2

- ^O'Hart, pp. 183–85

- ^Cusack, p. 6 ff

- ^Coogan, pp. 5–6

- ^O'Hart

- ^Byrne,passim;Charles-Edwards,passim

- ^Westropp, Ancient Churches in Co. Limerick, page 332-333

- ^Lewis, Topographical Dictionary, under the word Mahonagh

- ^"Genealogical Memoir of the O'Donovans, formerly Kings of Ui Fidgheinte" C. L. Nono & Son, Printers and Stationers Ennis, Co. Clare, Ireland 1902

- ^Stokes 1887, pp. 202–5

- ^Byrne 2001, p. 243

- ^Ó Coileáin 1981, p. 133

- ^FitzPatrick

- ^p.123

- ^abBegley 1906

- ^Joyce 1903 vol. II, pp. 101–2

- ^Placenames Database of Ireland[permanent dead link]

- ^FitzPatrick 2004, pp. 131–2

- ^Gógan 1932

- ^Begley 1906

- ^Appendix to the Annals of the Four Masters, edited by John O'Donovan, page 2432

- ^Meyer 1901

- ^Byrne 2001, p. 178

- ^Byrne 2001, p. 197

- ^abcO'Hart 1892

- ^Todd 1867

- ^Annals of Inisfallen1177.4

- ^Annals of Inisfallen1189.3

- ^see edition by Ó Corráin 1997

- ^Ó Corráin 1997

- ^O'Leary of Uí Fidgenti(O'Hart 1892)

- ^Coogan, Tim Pat (2002).Michael Collins: The Man Who Made Ireland.Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 5–6.ISBN0312295111.

- ^ed. Ó Corráin 1997, p. 195 (176)

Bibliography

[edit]- Begley, John,The Diocese of Limerick, Ancient and Medieval.Dublin: Browne & Nolan. 1906.

- Byrne, Francis John,Irish Kings and High-Kings.Four Courts Press. 2nd revised edition, 2001.

- Charles-Edwards, T.M.,Early Christian Ireland.Cambridge. 2000.

- Coogan, Tim Pat,Michael Collins: The Man Who Made Ireland.Palgrave Macmillan. 2002.

- Cormac mac Cuilennáin,and John O'Donovan (tr.) with Whitley Stokes (ed.),Sanas Cormaic,orCormac's Glossary.Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society. Calcutta: O. T. Cutter. 1868.

- Cusack, Sister Mary Frances,Life of Daniel O'Connell, the Liberator: His Times – Political, Social, and Religious.New York: D. & J. Sadlier & Co. 1872.

- FitzPatrick, Elizabeth,Royal Inauguration in Gaelic Ireland c. 1100–1600: A Cultural Landscape Study.Boydell Press. 2004.

- Gógan, Liam S.,The Ardagh Chalice.Dublin. 1932.

- Joyce, Patrick Weston,A Social History of Ancient Ireland, Vol. IandA Social History of Ancient Ireland, Vol. II.Longmans, Green, and Co. 1903.

- Geoffrey Keating,with David Comyn and Patrick S. Dinneen (trans.),The History of Ireland by Geoffrey Keating.4 Vols. London: David Nutt for the Irish Texts Society. 1902–14.

- Kelleher, John V., "The Rise of the Dál Cais", in Étienne Rynne (ed.),North Munster Studies: Essays in Commemoration of Monsignor Michael Moloney.Limerick: Thomond Archaeological Society. 1967. pp. 230–41.

- MacNeill, Eoin,"Early Irish Population Groups: their nomenclature, classification and chronology",inProceedings of theRoyal Irish Academy(C) 29.1911. pp. 59–114

- Mac Spealáin, Gearóid,Uí Cairbre Aobhdha.Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. 1960.

- Mac Spealáin, Gearóid,Ui Conaill Gabhra i gContae Luimnigh: A Stair (A History of West County Limerick).Limerick: Comhar-chumann Ide Naofa. 2004.

- Meyer, Kuno(ed. & tr.), "The Expulsion of the Dessi", inY Cymmrodor 14.1901. pgs. 101-35. (also availablehere)

- Meyer, Kuno (ed.),"The Laud Genealogies and Tribal Histories",inZeitschrift für Celtische Philologie 8.Halle/Saale, Max Niemeyer. 1912. Pages 291–338.

- Meyer, Kuno (ed. & tr.),"The Song of Créde daughter of Guaire",inÉriu 2(1905): 15–17. (translation availablehere)

- Murphy, Gerard (ed.), "The Lament of Créide, Daughter of Gúaire of Aidne, for Dínertach, Son of Gúaire of the Ui Fhidgente", in Gerard Murphy (ed.),Early Irish Lyrics: Eighth to Twelfth Century.Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1956. pp. 86–88. Also known asIt é saigte gona súain(comp. Donnchadh Ó Corráin 1996)

- Ó Coileáin, Seán, "Some Problems of Story and History", inÉriu 32(1981): 115–36.

- O'Connell, Mary Ann Bianconi,The Last Colonel of the Irish Brigade: Count O'Connell.London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Co. 1892.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh(ed.),Genealogies from Rawlinson B 502.University College, Cork: Corpus of Electronic Texts. 1997.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh, "Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland", in Foster, Roy (ed.),The Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland.Oxford University Press. 2001. pgs. 1–52.

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí(ed.),A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland, Vol. 1.Oxford University Press. 2005.

- O'Donovan, John(ed. & tr.),Annala Rioghachta Eireann. Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, from the Earliest Period to the Year 1616.7 vols. Royal Irish Academy. Dublin. 1848–51. 2nd edition, 1856.

- O'Hart, John,Irish Pedigrees.Dublin. 5th edition, 1892.

- O'Keeffe, Eugene (ed. & tr.),Eoganacht Genealogies from theBook of Munster.Cork. 1703. (availablehere)

- O'Rahilly, Thomas F.,Early Irish History and Mythology.Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.1946.

- Rynne, Etienne (ed.),North Munster Studies: Essays in Commemoration of Monsignor Michael Moloney.Limerick. 1967.

- Sproule, David,"Origins of the Éoganachta",inÉriu 35(1984): pp. 31–37.

- Sproule, David,"Politics and pure narrative in the stories about Corc of Cashel",inÉriu 36(1985): pp. 11–28.

- Stokes, Whitley(ed. & tr.),The Tripartite Life of Patrick.London: Eyre and Spottiswoode for Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1887.

- Todd, James Henthorn(ed. and tr.),Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh: The War of the Gaedhil with the Gaill.Longmans. 1867.

- Westropp, Thomas Johnson,"A Survey of the Ancient Churches in the County of Limerick", inProceedings of the Royal Irish AcademyVolume XXV, Section C (Archaeology, Linguistic, and Literature). Dublin. 1904–1905. Pages 327–480, Plates X-XVIII.

External links

[edit]- The Territory of Thomonddiscusses the extent of the Kingdom of Uí Fidgenti

- Tuadmumuhas maps and convenient Uí Fidgenti-related genealogies

- Tribes & Territories of Mumhan

- Tracys of the Eóganachtafeatures a very detailed genealogy of the Uí Fidgenti, compiled and translated from numerous primary and secondary sources

- South Irish R1b