Costache Aristia

Costache Aristia | |

|---|---|

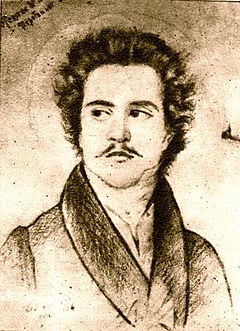

Louis Dupré's portrait of Costache Aristia, ca. 1824 | |

| Born | Constantin Chiriacos Aristia (Konstantinos Kyriakos Aristias) 1800 Bucharest,WallachiaorIstanbul,Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 18 April 1880 (aged 79 or 80) Bucharest,Principality of Romania |

| Occupation | actor, schoolteacher, translator, journalist, soldier, politician, landowner |

| Nationality | Wallachian Romanian |

| Period | c.1820–1876 |

| Genre | epic poetry,lyric poetry,tragedy,short story |

| Literary movement | Neoclassicism,Romanticism |

| Signature | |

| |

CostacheorKostake Aristia(Romanian pronunciation:[kosˈtakearisˈti.a];bornConstantin Chiriacos Aristia;Greek:Κωνσταντίνος Κυριάκος Αριστίας,Konstantinos Kyriakos Aristias;transitional Cyrillic:Коⲛстантiⲛꙋ Aрiстia,Constantinŭ Aristia;1800 – 18 April 1880) was aWallachian-born poet, actor and translator, also noted for his activities as a soldier, schoolteacher, and philanthropist. A member of theGreek colony,his adolescence and early youth coincided with the peak ofHellenizationin bothDanubian Principalities.He first appeared on stage atCișmeaua RoșieinBucharest,and became a protege ofLady Rallou.She is claimed to have sponsored his voyage to France, where Aristia became an imitator ofFrançois-Joseph Talma.

Upon his return, Aristia took up the cause ofGreek nationalism,joining theFiliki Eteriaand flying the "flag of liberty" for theSacred Band.He fought on the Wallachian front during theGreek War of Independence,and was probably present for thedefeat at Drăgășani.He escaped the country and moved between various European states, earning protection from theEarl of Guilford,before returning to Bucharest as a private tutor for theGhica family.Aristia used this opportunity to teach drama and direct plays, and thus became one of the earliest contributors toRomanian theater.A trendsetter in art and fashion, he preserved his reputation even as Wallachians came to reject Greek domination. He adapted himself to their culturalFrancization,publishing textbooks for learning French, and teaching both French andDemotic GreekatSaint Sava College.

Under theRegulamentul Organicregime, Aristia blended Eterist tropes andRomanian nationalism.He became a follower ofIon Heliade Rădulescu,and helped set up the Philharmonic Society, which produced a new generation of Wallachian actors—includingCostache Caragialeand Ioan Curie. He contributed to the effort ofmodernizing the language,though his own proposals in this field were widely criticized and ultimately rejected. Aristia was made popular by his translation ofVittorio Alfieri'sSaul,which doubled as a nationalist manifesto, and earned accolades for his rendition of theIliad;however, he was derided for eulogizingPrinceGheorghe Bibescu.He also contributed to cultural life in theKingdom of Greece,where, in 1840, he published his only work of drama.

Aristia participated in theWallachian Revolution of 1848,when, as leader of the National Guard, he arrested rival conservatives and publicly burned copies ofRegulamentul Organic.During the backlash, he was himself a prisoner of theOttoman Empire,and was finally expelled from Wallachia. He returned in 1851, having reconciled with the conservative regime ofBarbu Dimitrie Știrbei,and remained a citizen of theUnited Principalities.He kept out of politics for the remainder of his life, concentrating on his work at Saint Sava, and then at theUniversity of Bucharest,and on producing another version of theIliad.Among his last published works are Bible translations, taken up under contract with theBritish and Foreign Bible Society.

Biography

[edit]Youth

[edit]Aristia is generally believed to have been born inBucharest,the Wallachian capital, in 1800. The date was pushed back to 1797 in some sources, but Aristia's relatives denied that this was accurate.[1]In 1952, folklorist Dimitrios Economides, who conducted interviews with the Aristia family, argued that Costache was born inIstanbul,capital of theOttoman Empire,"around the year 1800".[2]At the time of his birth, Wallachia andMoldavia(the twoDanubian Principalities) were autonomous entities of the Ottoman realm; Greek cultural dominance andHellenization,represented primarily byPhanariotes,were at their "great acme".[3]Though seen by scholar Petre Gheorghe Bârlea asAromanianby origin,[4]Aristia himself noted that, on his paternal side at least, he was a "good Greek". He described his relationship with Wallachia in terms of voluntary assimilation, as advised by his father:Fii grec și român zdravăn, fii recunoscător( "Be steadfast as a Greek and a Romanian, be thankful" ).[5]Immersed in Greek culture, he still had virtually no understanding of written Romanian until 1828.[6]

Costache entered Bucharest's Greek School during the reign ofPrinceJohn Caradja,a Phanariote.[7][8]His teachers there included philologist Constantin Vardalah.[1]According to one late report by researcherOctav Minar,Aristia also debuted as a teacher of drama upon his return to Bucharest, at some point before 1815. His first-generation students supposedly included Stephanos "Natis" Caragiale, grandfather of the Romanian dramatistIon Luca Caragiale.[9]Before graduating, Aristia himself was an actor for the open-air venue atCișmeaua Roșie.[7][10]ScholarWalter Puchner,who dates these events to "the spring and autumn of 1817", questions the accuracy of historical records, noting that they contradict each other on the details;[11]according to memoirist and researcherDimitrie Papazoglu,Cișmeauawas in fact managed by "director Aristias".[12]At that stage, acting in Wallachia was an all-male enterprise, and Aristia appeared as a female lead,in drag.[13]TheCișmeauatroupe was sponsored by Caradja's daughter,Lady Rallou.According to various accounts, she was impressed by Aristia's talent, and reportedly sent him abroad, to theKingdom of France,for Aristia to study underFrançois-Joseph Talma.[7][14]The details of this claim are disputed. ResearcherIoan Massoffnotes that Aristia was never a member of Talma's acting class, but only a regular spectator to his shows, and after that his imitator.[15]Puchner questions whether this trip ever took place, since "no evidence has surfaced for [Aristia's] stay in Paris."[16]

The Aristias rallied to the cause ofGreek nationalismshortly before theGreek uprising of 1821.Young Aristia joinedAlexander Ypsilantis's secret society, theFiliki Eteria,[2][7][17]which slowly engineered the nationalist expedition in Moldavia and Wallachia. In late 1818 and early 1819, a new Prince,Alexandros Soutzos,allowed Aristia and his troupe to perform works ofpolitical theater,portraying the "hatred of tyranny and self-sacrifice for the fatherland" —fromLa Mort de CésarandMérope,byVoltaire,toIakovakis Rizos Neroulos'Aspasia.They were met with "frenetic applause, exuberance and overflowing emotions".[18]Soutzos was troubled by this reception, and decided to ban all plays that could be construed as critiques of religion and political affairs. He was ignored by the troupe, who answered more directly to a group of Eterist conspirators; they continued with provocative stagings of plays by Voltaire andVittorio Alfieri,until May 1820, by which time local Greeks were in full preparation for the revolution.[19]

Aristia awaited the Eterists in Bucharest, which had been occupied by troops loyal toTudor Vladimirescu,who led aparallel uprising of Romanians.In mid March 1821, Greeks in Bucharest, led byGiorgakis Olympios,pledged to support Ypsilantis rather than Vladimirescu. The event was marked by a large display of Greek nationalism in downtown Bucharest, the details of which were committed to writing byConstantin D. Aricescufrom his interview with Aristia.[20]The actor carried the "flag of liberty", an Eterist symbol showingConstantine the GreatandHelena,alongside a cross and the slogan "In this, conquer";the obverse showed aphoenixrising from its ashes.[21]The ceremony ended with the banner being planted on the Bellu gate, announced to the crowds as prefiguring the future reconquest ofByzantium.[22]Reportedly, "the flag that was carried by Mr. Aristia" was later also adopted bySava Fochianos,who deserted to Ypsilantis'Sacred Bandalongside the Bucharest garrison.[23]

In April–August, Ypsilantis' forces were encircled and crushed by theOttoman Army.According to various accounts, Aristia fought alongside the Sacred Band of Wallachia in theirfinal stand at Drăgășani,side by side with a fellow actor, Spiros Drakoulis.[2]He was seriously wounded on that battlefield,[24]before receiving sanctuary in theAustrian Empire.[25]He eventually settled in thePapal States,where he reportedly continued his education and became familiar with Italian theater.[26]Performing in charity shows for destitute children, in or around 1824 he metLouis Dupré,who drew his portrait.[27]Also at Rome, Aristia met theEarl of Guilford,and later claimed to have received his quasi-parental protection.[6]Meanwhile, Costache's actual father had enlisted to fight for theFirst Hellenic Republic,and was later killed at theSiege of Missolonghi.[5][7][8]

Returning to his native Wallachia, Aristia found work as a private tutor for young members of theGhica family—whose patriarch,Grigore IV Ghica,had taken the Wallachian throne in 1822. His patron, Smărăndița Ghica, also asked him to stageNeoclassicalplays in Greek at her Bucharest home. Regulars included the future politician and memoirist,Ion Ghica,who was also directly tutored by Aristia.[28]According to Ghica, Aristia reserved the title roles for himself, while Smărăndița andScarlat Ghicahad supporting roles; their costumes were improvised from bed linen and old dresses.[29]Ghica describes his teacher as an "epic" and "fiery" character, noting in passing that Aristia was also promoting themodern Western fashion,including thetailcoat,having discarded allOttoman clothingafter 1822.[30]

This period also witnessed the first coordination between Aristia and a Wallachian writer,Ion Heliade Rădulescu.Inspired by the latter, in 1825 Aristia produced and performed inMolière'sGeorge Dandin,turning it into an anti-Phanariote manifesto.[31]It remains the only work by Molière ever to be brought on stage in Wallachia, despite many translations of his other plays.[32]Also in 1825, Aristia traveled toBritish Corfu,performing in his own Greek rendition of Voltaire'sMahomet.[33]Sponsored by Guilford,[2][6]he finally graduated from theIonian Academy.During his time there, he staged Alfieri'sOreste,Agamemnon,andAntigone,Pietro Metastasio'sDemofoonte,andJean Racine'sAndromaque.[2]Puchner also mentions that Aristia eventually taught classes at the academy.[34]

Economides suggests that Aristia had returned to Bucharest in 1827, joining the staff ofSaint Sava Collegeas a teacher of French;[2]other records have him in Paris, where Aristia completed an hymn celebrating the Hellenic Republic. It was first published byFirmin Didotin 1829.[6]Meanwhile, the anti-Ottoman trend received endorsement following theRusso-Turkish War of 1828–1829,which placed Wallachia and Moldavia under a modernizing regime, defined by theRegulamentul Organicconstitution. His hymn was published as a brochure by Heliade's newspaperCurierul Românesc,which thus hinted at Romanian national emancipation.[35]One account byIosif Hodoșiusuggests that Aristia returned to his activities on the stage during the actual occupation, in the interval following Grigore Ghica's ouster. His "timid attempt" included shows of Alfieri'sBrutoandOreste,the latter withC. A. RosettiasAegisthus(displaying "such natural ferocity that he frightened the public, and even his teacher, Aristia" ).[36]

Philharmonic Society

[edit]

Aristia's conversion toRomanian nationalism,or the "ideals of the Romanian national community", is noted by historian Nicolae Isar as being exemplary for a generation of assimilated Greeks.[37]The poet was initially threatened by the overwhelming prestige of French culture, which marginalized Greek influence: he reportedly lost students to the new French school, founded byJean Alexandre Vaillant.[38]However, he compensated by exploiting his own French literary background. He is thus credited as a contributor to Heliade's Romanian version ofMahomet,which appeared in 1831.[39]Despite his acculturation, Aristia continued to publicize the staples of "Eterist dramatic repertoire", which included bothMahometandLord Byron'sSiege of Corinth.[40]From November 1832, headmasterPetrache Poenaruemployed Aristia to teach French andDemotic Greekat Saint Sava.[41]He also gave informal classes in drama and had a series of student productions involving Rosetti andIon Emanuel Florescu;during these, Rosetti "revealed himself as a very gifted thespian".[42]

Aristia also discovered and promoted a Bucharest-born tragedian, Ioan Tudor Curie. He continued to have an influence on fashion: most students, above all Curie and Costache Mihăileanu, imitated their teacher's every mannerism. Because of Aristia, a generation of actors "trilled and swagged", wore their hair long, and put on "garish" neckties.[15]Students from those years included Natis Caragiale's son,Costache Caragiale,who debuted in 1835 as Curie'sunderstudy.[43]As reported by Curie himself, it was Aristia who took the initiative in transforming irregular theatrical classes into a more structured drama club: "He was famous artist, a good painter, an architect, a sculptor, a poet. He had great, solid ideas about each and everything. He wanted a classical theater; he proceeded by searching through the libraries of Greek monks, those who were present at Bucharest, for those books showing Arab and Jewish costumes and from these antique models he created the theater's wardrobe, sewing them together himself, out of fine cloth, [and] creating a historically accurate scene".[44]Aristia received encouragement from theboyar nobility,who had heard of his "performing wonders" as an educator, but also from the Russian Governor-general,Pavel Kiselyov.Kiselyov visited Aristia to make sure that the gatherings were non-political in content, after which he gave his personal blessing.[44]

By 1833, Aristia had become a regular inliberal circles,meeting with his pupil Ghica and other young intellectuals. Together with Heliade, they established a Philharmonic Society.[36][45]He organized classes in acting and declamation at the Dramatic School, a branch of the Philharmonic Society.[7][46]This was the first learning institution for professional acting to exist in theBalkans.[47]Alumni included three of Wallachia's pioneer actresses, Caliopi Caragiale, Ralița Mihăileanu,[48]andEufrosina Popescu,as well as the future playwrightDimitrie C. Ollănescu-Ascanio.[49]From November 1, 1835, Aristia and his mentor Heliade were editors of its mouthpiece,Gazeta Teatrului.[50]That year, he also published a textbook onFrench grammar,reprinted in 1839 asPrescurtare de grammatică françozească.It was closely based onCharles Pierre ChapsalandFrançois-Joseph-Michel Noël'sNouvelle Grammaire Française.[51]He followed up with a series of French-language courses, including aphrase bookand a translation of J. Wilm's book of moral tales.[51]

The Philharmonic put up plays by foreigners—the only exception to this rule was a reported staging ofCostache Faca'sComodia vremii,in 1835.[52]Mahometwas a favorite with the public—Aristia did not appear in it, but served as aprompter.[44]According to Hodoșiu, the Philharmonic had "incalculable" success with this play, which ensured that the group could count on a 2,000-ducatbudget.[36]Other productions riled up conservative sensitivities, as was the case withAugust von Kotzebue'sMisanthropy and Repentance.It promptedBarbu Catargiuto report that the Philharmonic had failed in its stated mission of serving as the "school of morals".[36]Aristia's subsequent work was a translation of Alfieri'sSaulandVirginia,initially commissioned and produced by the same Society.[53]It was never printed, but served as the basis for a show on December 1, 1836.[54]He prepared, but never managed to print, Molière'sForced Marriage.[55]

In 1837, Aristia also published his version ofHomer'sIliad,which included his short biography of the author.[7][56][57]The published version also featured Aristia's notes, outlining answers to his earliest critics, whom he called "Thersites".[56]Wallachia's rulerAlexandru II Ghicawas enthusiastic about the work, and presented Aristia with congratulations, expressed for all his subjects.[58]This is sometimes described as the firstIliadtranslation into Romanian;[59]some evidence suggests that Moldavia'sAlecu Beldimanhad produced another one ca. 1820,[60]around the time whenIordache Golescualso penned a fragmentary version.[61]

Saulwas the Society's other major success: it doubled as a patriotic play, with messages that theatergoers understood to be subversively aimed at occupation by theRussian Empire.Russian envoys took offense, and the production was suspended.[62]Its noticeable opposition to Alexandru II, and financial setbacks, put an end to the Philharmonic Society during the early months of 1837. Aristia's pupils attempted to take up similar projects, but generally failed to build themselves actual careers.[63]Exceptions included Costache Caragiale, who was able to find employment atBotoșaniin Moldavia,[64]as well as Eufrosina Popescu[65]and Ralița Mihăileanu,[48]who were leading ladies in Bucharest until the late 1870s. By May 1837, Aristia himself had traveled to Moldavia, accompanying Heliade on a networking trip and hoping to coordinate efforts between dissenting intellectuals from both Principalities.[66]Samples of his poetry were taken up inMihail Kogălniceanu's review,Alăuta Românească.[67]

At home, the Ghica regime continued to bestow accolades upon the poet. In 1838, he was received into boyardom after being created aSerdar;in January 1836, he had married the Romanian Lucsița Mărgăritescu.[68]Around that time, Aristia was inhabiting a townhouse to one side of Bucharest's Lutheran Church (Luterană Street), where he also hosted the city's first state-sanctioned girls' school.[69]His father in law,SerdarIoan Mărgăritescu, granted the couple a vineyard in the unincorporated neighborhood ofGiulești,and various assets worth 35,000thaler.[70]Costache and Lucsița's first-born was a son, found dead at the age of three; a daughter, Aristeea Aristia, was born to them in 1842.[5]

Aristia's school of acting, still heavily reliant on Talma, was nominally realistic, or "somewhat naturalistic", in that it relied onsubstitution.However, he pushed his pupils to exaggerate, causing them "nervous wear and tear" to the point of compete exhaustion.[71]Curie was recalled to play the lead inSaulduring December 1837, and acted with such pathos that he fainted. Doctors intervened todraw blood,prompting Heliade to remark that Curie had "shed his blood for the honor of Romanian theater".[15]Reportedly, some at Ghica's court were impressed by the event, and inquired about "the emperor" Curie's health.[72]Although the play could go back into production from January 1838, and also taken up by Caragiale's troupe in Moldavia,[73]Heliade and Aristia's activity was interrupted by major setbacks. As reported by Hodoșiu, "indirect persecutions", showing Alexandru II's mounting jealousy, but also conflicts within the Society itself, again brought Aristia's work to a standstill. The Philharmonic ceased functioning whenIeronimo Momoloended their lease on his theater hall.[36]

Athens sojourn and 1848 Revolution

[edit]By 1839, Prince Ghica had engineered Heliade's political marginalization; the only two Heliade loyalists to still declare publicly were Poenaru and Aristia.[74]During those months, the conservative schoolteacherIoan Maiorescupublished a detailed critique of Wallachia's educational system, prompting Aristia to take up its defense.[75]Around that time, Aristia and Curie went on a theatrical tour of theKingdom of Greece,[76]where the former set up a Philodramatic Society.[2][8]His cultural manifesto, addressed to the Greek people, was published on 25 September 1840. It won him instant support from other former Eterists relocated to Athens, including his mentor Rizos Neroulos, as well as from the deposed Prince John Caradja. Aristia's text was a critique ofmelodramaas favored by the foreign courtiers ofKing Otto,attracting their opposition to his projects; they promoted Aristia's rival,Theodoros Orfanidis.[2]Aristia and is troupe are only known to have performed a single play in Athens. This wasAristodemo,byVincenzo Monti,which he himself translated into Greek; it premiered on 24 November 1840.[2]According to one anecdote, Aristia "so very much scared those dames of reborn Hellada with the realism of his acting, that some just fainted."[77]

Also in 1840, a printing press in Athens put out Aristia's only original work of drama, the tragedyΑρμόδιος και Ἀριστογείτων( "Harmodius and Aristogeiton").[78]Dissatisfied with the Ottonian regime, the author privately confessed that he longed to make his definitive return to Wallachia, "among those goodDacians".[2]He did so before October 1843, and served as co-editor of Poenaru's newspaper,Învățătorul Satului.This was the first publication specifically aimed at educating Wallachia's peasants, and was distributed by rural schools.[79]Aristia held his own column in the form of "moralizing tales",Datoriile omului( "Man's Duties" ), sometimes inspired by historical episodes from the times ofMircea the ElderandMatei Basarab.These alternated "careful pledges of submission to law and the authorities" with "critical notes against injustice and abuse by those in power."[80]Curie, meanwhile, opted not to return to his homeland, signing for theFrench Foreign Legion;he later settled in Moldavia.[81]

Those years also witnessed Aristia's enthusiasm for political change in Wallachia: also in 1843, he publishedPrințul român( "The Romanian Prince" ), which comprises encomiums forGheorghe Bibescu,winner of therecent princely election.[82]This was followed in 1847 by a similar work onMarițica Bibescu,published asDoamna Maria( "Lady Maria" ).[6]In 1845, he had also produced a third and expanded edition of his work on French grammar.[51]He was nevertheless struggling to make ends meet. By 1847, his two Bucharest homes had been taken by his creditors, and Lucsița had prevented his access to her dowry.[6]Despite his participation in the princely cult, Aristia was being driven into the camp opposing Bibescu's relative conservatism. He now "totally integrated" within the Romanian national movement, emerging as a member of the liberal conspiratorial society,Frăția.[7]Historian Mircea Birtz hypothesizes that he was also initiated into theRomanian Freemasonry,but notes that the organization itself never claimed him.[83]According to historianDumitru Popovici,Aristia was aware of how his non-Romanianness clashed with revolutionary ideals; like Caragiale andCezar Bolliac,he compensated with "grandiloquent gestures" that would display his affinities with locals.[84]

The poet reached his political prominence in June 1848, with the momentary victory of theWallachian Revolution.During the original uprising, he agitated among Bucharest's citizens, reciting "revolutionary hymns".[85]Following Bibescu's ouster, the Provisional Government established a National Guard, and organized a contest to select its commander. Papazoglu recalls that Aristia was the first Guard commander, elected by the Bucharest citizenry with an acclamation on the field of Filaret.[86]Other accounts suggest that Aristia presented himself as a candidate, but lost to government favoriteScarlat Crețulescu,and was only appointed a regular member for one Bucharest's five defense committees.[87]According to Aricescu, Aristia and Nicolae Teologu were supported by the populace, who gathered at Filaret to protest against Crețulescu's selection. This prompted the authorities to censure them with a proclamation against "anarchy"; as read by Aricescu, the document proved that Aristia and Teologu, as Heliade disciples, were less left-wing than Rosetti and other "demagogues", who made up most of the revolutionary cabinet.[88]

On July 7 (Old Style:June 25), Crețulescu resigned, freeing his seat for Aristia.[89]According to Papazoglu, entire sections of the National Guard existed only on paper. Those that did exist comprised regular members of the cityguildsin their work uniforms, who amused the populace with their poor military training.[90]During his period as a revolutionary officer, Aristia himself helped carry out the clampdown on Bibescu loyalists. According to Heliade, the reactionary leaderIoan Solomonwas captured by "Constantin Aristias, a colonel in the national guard, who enjoyed the People's great confidence". Heliade claims that Aristia saved Solomon from a near-lynching, ordering his protective imprisonment atCernica.[91]Another target of revolutionary vengeance wasGrigore Lăcusteanu,whose memoirs recall an encounter with "Aristia (hitherto a demented acting coach) and one Apoloni, armed to their teeth, their hats festooned with feathers."[92]Lăcusteanu also claims that he easily tricked Aristia into allowing him to lodge with a friend,Constantin A. Crețulescu,instead of being moved into an actual prison.[93]

Shortly after, Aristia resigned and was replaced with Teologu. He remained enlisted with the Guard, helping its new commander with the reorganization.[94]According to one later record, Aristia also served as a revolutionaryPrefectofIlfov County(which included Bucharest).[95]Învățătorul Satului,directed by the radicalNicolae Bălcescufrom July 1848, employed the poet on its editorial team.[96]Over three issues, it published his unabashed political essay,Despre libertate( "On Liberty" ).[97]In September, the Revolution itself took a more radical turn: at a public rally on September 18 (O. S.: September 6),Regulamentul OrganicandArhondologia(the register oftitles and ranks) were publicly burned. Aristia and Bolliac participated in this event and gave "firebrand speeches."[98]As reported byColonel Voinescu,the conservative memoirist, the "ridiculous parody" was entirely organized by "a Greek man, namely C. Aristia". Voinescu muses: "What should we call such an act? Which nation has ever set fire to its own laws before even making herself some new ones! but there is some consolation in the knowledge that the chief leader of this display was a Greek."[99]

Imprisonment, deportation, and return

[edit]The drift into radicalism was finally curbed by a new Ottoman intervention, which ended the Revolution altogether. As leader of the occupation force,Mehmed Fuad Pashaordered a roundup of revolutionaries. Aristia was imprisoned atCotroceni Monastery,part of a prison population which also included Bălcescu, Bolliac, Rosetti,Ion C. Brătianu,Ștefan Golescu,Iosafat Snagoveanu,and various others; people less implicated in the events, such asDimitrie Ghica,were released back into society.[100]On September 24, Fuad andConstantin Cantacuzinosigned an order to banish Aristia and other rebels from Wallachia.[101]The early leg of his deportation journey was a boat trip up theDanube,alongside his fellow poet-revolutionaryDimitrie Bolintineanu,as well Bolliac, Snagoveanu, Ștefan Golescu,Nicolae Golescu,Alexandru Golescu-Albu,andGrigore Grădișteanu.[102]OutsideVidin,Aristia wanted to pass the time by reciting fromSaul,before being struck down by his Turkish guard—unfamiliar with theater, he feared that Aristia had gone insane.[103]

According to one account, Aristia was due to be executed alongside other radicals, but got hold of thefirmanand was able to modify its text before it reached his would-be executioners.[27]Other reports note the intervention ofUnited Kingdomdiplomats, includingEffingham Grant,who feared that Aristia and the others would end up as Ottoman prisoners in Istanbul, or handed over to the Russians. In October, Grant met the hostages near Vidin, noting that they were "in a most wretched state".[104]Aristia was finally taken with the other exiles toAda Kaleh,some 160 kilometers upstream, where the revolutionaries negotiated crossing into Austrian territory by way ofSemlin—in effect, an escape from custody.[105]Eventually, the group came ashore into a rural part of theBanat,controlled by local Romanians, who defended the Austrian cause against the breakawayHungarian revolutionaries;Snagoveanu was able to persuade the peasants that the new arrivals, though revolutionary exiles, were not friends of the Hungarians, and that they could be granted safe conduct.[106]

The second part of the journey took Aristia intoAustrian Transylvania,alongsideIon Ionescu de la Brad.The latter recalled in 1850: "I had the misfortune of spending 40 days on the Danube with this creature [Aristia], and then on our way toBrașovwe almost wrestled over me jibing at Heliade and the Phanariotes. "[107]A committed supporter of Heliade's post-revolutionary faction,[108][109]Aristia successively lived in Brașov, Paris, Istanbul, and Athens.[110]In February 1849, "Provisional Government members and delegates of the Romanian emigration", including Heliade and Aristia, signed a letter of protest addressed primarily to theFrankfurt Parliament,asking for an international opposition to Russian intrusion into Wallachian political life. They asserted: "Astributaries of the Sublime Porteand [in that] autonomous, Romanians, having fulfilled all their obligations toward the Ottoman Court, can now only place themselves under the protections of those powers interested in Turkish independence. "[111]

Aristia took Heliade's part in his conflict with fellow exile Bălcescu, accusing the latter of having squandered funds collected for the revolutionary cause.[109]In July 1849, a common resolution by the Russian and Ottoman governments named him among the 34 individuals "who have taken part in the disorders of Wallachia", and whose entry in either Principality was to be prevented by force.[112]A report byAlexandru Golescu-Arăpilăinforms that in May 1850 Aristia was stranded in Vienna, unable to continue his European journeys after a financial "blunder".[113]As noted by the same Arăpilă, such episodes did not prevent Aristia from presenting the financial situation of revolutionary cells in unrealistic terms, and to promise wonders (monts et merveilles).[114]The poet had refused an offer of naturalization by Greece,[115]and instead was seeking to follow Heliade's example and begin serving the Ottomans; for this reason, he traveled toRuschuk.[116]

Aristia also made ample efforts to be allowed back into Wallachia—Bibescu's brother,Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei,was by then the country's reigning Prince. By July 1850, Aristia had written several letters to both Știrbei and his Ottoman supervisors asking that he and his wife be forgiven. These letters show that he had buried two children and had one living daughter, Aristeea Aristia, as "my only fortune in this world."[117]Știrbei gave his approval, and on September 13 a decree was issued allowing him and his family to cross the border; they did so in 1851.[118]He now helped establish the prototypeNational Theater Bucharest.Together with Costache Caragiale, he participated in the very first production of a play by that institution, on December 31, 1851.[8]The family moved back into their home at Giulești, where they began tending to their vineyard and opened a number ofsand mines.The property increased from various purchases, but Aristia donated some of the plots to low-income families.[1]

Aristia returned to print in 1853[7]with a series of moral tales,Săteanul creștin( "The Christian Villager" ). It carried a dedication to the Princess-consort, Elisabeta Cantacuzino-Știrbei.[51]Aristia continued to be active during Știrbei's second reign, which began in October 1854. That year, his scattered poems were collected in an almanac put out by the Romanians ofGroßwardein.[119]For a while in September 1855, the Prince considered making Aristia his State Librarian.[120]Becoming aCaimacam(Regent) in 1856, after theCrimean Warhad put an end to Russian interventions,Alexandru II Ghicafinally awarded him that same office.[121]In 1857–1858, he andCarol Valștain,as employees of the fledgling Wallachian National Museum, worked to recover and store art bequeathed byBarbu Iscovescu,a painter and revolutionary figure who had died in exile atPera.[122]Săteanul creștinwas followed in 1857 by a first volume fromPlutarch'sParallel Lives,[7][123]including a biographical essay byDominique Ricard.[6]As he explained in an announcement put out byFoaia pentru Minte, Anima si Literatura,this activity had consumed him for the previous four years. He also credited its success to grants awarded by two Wallachian Ministers of Education—his former enemy Scarlat Crețulescu, and his one-time Philharmonic colleague,Ioan Câmpineanu.[124]

Final activities

[edit]

Though resuming his literary activities, Aristia declared himself frustrated in his work as a translator by the lack of a literary standard, including in matters ofRomanian Cyrillic orthography.He considered giving up on this activity.[125]Also in 1857, after being contacted by theBritish and Foreign Bible Society(BFBS), Aristia began work on a Romanian Bible, for which he took on the signature "K. Aristias".[126]He used the "latest Greek edition", verified against theMasoretic Text.Three volumes, comprising all text betweenGenesisandIsaiah,was published in 1859 asBiblia Sacra.[127]In parallel, hisIliadhad reached heDuchy of Bukovina,acquired byEudoxiu Hurmuzachi;in this version, it served to familiarizeMihai Eminescu,the future poet, with Homer's work.[57]However, Aristia rejected his own translation,[5][128][129]and had by then produced a new one, ultimately published in 1858.[7]

In January 1859, Wallachia was effectively merged with Moldavia into theUnited Principalities,as the nucleus of modern Romania. Under this new regime, Aristia was again confirmed as a teacher of French and Greek at Saint Sava,[121]though some records also suggest that he only taught Greek atGheorghe Lazăr Gymnasium,from 1860 to 1865.[130]Also in 1859, Aristia published his final original work of verse,Cântare.Written from the point of view of children in an orphanage, it honored the musician and philanthropist Elisa Blaremberg.[6]His status was declining: by the 1850s, his and Talma's style of acting were being purged from theaters by a more realistic school, whose leading exponents wereMatei MilloandMihail Pascaly.[131]In 1860, the BFBS ended its contract with Aristia, who was demanding ever-increasing funds, and whose libertine lifestyle was viewed as distasteful by local missionaries.[132]P. Teulescu of theNational Archivesemployed him as a translator of Greek Wallachian documents from the age ofConstantine Mavrocordatos.As noted by historianNicolae Iorga,the activity fit in with Aristia's talents, as "somethinghe was good at "(Iorga's italics).[133]

In 1864, Costache and Lucsița Aristia were living on Stejar Street. They declared themselves "of Hellenic origin, of Romanian birth, [and] of Christian Orthodox religion".[134]His daughter Aristeea married the biologist Dimitrie Ananescu that same year; the younger Alexandrina was from 1871 the wife of Alexandru Radu Vardalah.[135]Following the transformation of Saint Sava, Costache was assigned a chair at the newUniversity of Bucharest,but resigned in favor of his pupil Epaminonda Francudi.[27]In the 1870s part of his Giulești vineyard was taken over by the Romanian state.[136]

Aristia was largely inactive during the final two decades of his life. In April 1867, he endorsedConstantin Dimitriade's effort to introduce more rigorous acting through a translation ofJoaquín Bastús' manual,Tratado de Declamación.It appeared that same year, but proved to be "tedious, complicated, and quickly outdated."[137]One other exception was an 1868 article forAteneul Român,where he campaigned for the adaptation of Romanian poetry to classicalhexameters.[138]That same year, Bolliac's newspaper,Trompetta Carpaților,asked Romanian authorities to sponsor Aristia's complete translation of theIliad,including its eventual publication.[139]This stance was being largely ignored by the new cultural mainstream, formed aroundJunimea,which favored the shedding ofLatin prosodyin favor of more natural patterns.[140]In a February 1876 issue ofConvorbiri Literare,JunimistȘtefan Vârgolicidescribed some of Aristia's lyrics as "very poorly written and very badly cadenced".[141]The group also promoted a less pretentious version of theIliad,as provided by its member,Ioan D. Caragiani.[56]

Completely blind from 1872, Aristia dictated his final poem, written in memory of philanthropistAna Davila,accidentally poisoned in 1874.[142]In May 1876, he received from the Romanian state theBene MerentiMedal, First class, at the same time asGrigore Alexandrescu,Dora d'Istria,andAaron Florian.[143]Beginning that year, the Aristias rented a home on Sfinții Voievozi Street, west ofPodul Mogoșoaiei,where Costache hosted a literary salon.[1]As noted by his grandson Constantin D. Ananescu, the aging and debilitated poet still rejoiced upon witnessing Romania's full emancipation from the Ottoman Empire with the1877–1878 War of Independence.[5]He died in his Sfinții Voievozi home[1]on April 18, 1880, after an "apoplexy".[144]His body was taken for burial at Sfânta Vineri Cemetery.[145]The state treasury provided 1000lei[146]for his "very austere" funeral.[27]The poet was survived by Aristeea Ananescu, his other daughter having died before him.[95]

Bucharesters preserved a record of the deceased writer in the name they assigned to his former property, asGropile AristiaorGropile lui Aristia( "Aristia's Pits" ). In 1891, a sanitation committee, presided upon by Alfred Bernard-Lendway, found that the remaining pits had gathered toxic water and were a source ofmalaria;the area was condemned and the pits were covered up.[147]Lucsița sold off the remainder of her husband's vineyard and mines to an entrepreneur named Viting, but her inheritors litigated the matter until ca. 1940. By then, the family house had been demolished to build a hospital for theState Railways Company,though the general area was still known for its namesake writer.[148]

Writing in January 1914, Ananescu noted that no arrangements had ever been made for his grandfather's centennial in 1900. This gaffe, he notes, was remedied in 1903, when Ollănescu-Ascanio produced a short historical play in which Aristia was a leading role.[5]The Aristia archive was by then mostly lost, as were most copies ofBiblia Sacra,[149]but hisSaulwas recovered and partly published by scholarRamiro Ortizin 1916.[150]By 1919, the boys' school on Bucharest's Francmasonă (or Farmazonă) Street had been renamed after the poet.[151]Aristia appears as a character inCamil Petrescu's 1953 novel,Un om între oameni—his "sentimental biography" provides the author with a pretext for discussing the world of theater and its political leanings and morals before and during 1848.[152]

Literary work

[edit]Aristia was widely seen as an important figure in the early modernizing stages ofRomanian literature.Speaking out againstJunimeain 1902, poetAlexandru Macedonskiasserted the role played by Heliade and his "constellation", including Aristia, with activating the "rejuvenation age" in Wallachia and Romania.[153]Among his later commentators,Walter Puchnerargues that Aristia was personally responsible for unifying the early traditions ofmodern GreekandRomanian theater.[154]A similar point is made by comparatist Cornelia Papacostea-Danielopolu, according to whom Aristia's activity in Greece "revived theatrical productions during the revolutionary period", while his work with the Ghica children signified the "origin of modern Romanian theater."[155]Philologist Federico Donatiello notes that Heliade and Aristia had a "keen interest" in transposing the theatrical canon of theAge of Enlightenmentinto Romanian adaptations.[156]Despite Aristia's Neoclassical references, literary historianGeorge Călinesculists him as one of Wallachia's firstRomantic poets—alongside Heliade, Rosetti, Alexandrescu,Vasile Cârlova,andGrigore Pleșoianu.[157]Theatrologist Florin Tornea also describes Aristia's acting as "murky [and] romantic".[158]

While his talents as an animator garnered praise, his lyrical work was a topic of debate and scandal. Early on, his poetry in Greek raised a political issue. Writing in 1853, philologist Alexandre Timoni noted that Aristia's hymn to Greece "lacked inspiration", but nonetheless had a "remarkable style."[159]Dedicated toAdamantios Korais,[58]this poem called on thegreat powersto intervene and rescue the country from Ottoman subjection. Aristia produced the image of Greece as a source of civilization, a sun around which all other countries revolved as "planets". According to Timoni, the hymn was an unfortunate choice of words: "it is this new kind of sun which, for all its splendor, rotates around [the planets]."[159]Aristia's other work in Greek,Αρμόδιος και Ἀριστογείτων,expanded upon a lyrical fragment from the work ofAndreas Kalvos,and similarly alluded to Greek liberation; it was dedicated to the EteristGeorgios Leventis.[58]

Aristia wrote during themodernization of the Romanian vernacular,but before the definition of standard literary language andLatin-based alphabet.Before his temporary disenchantment and pause, he considered Romanian especially apt for translating literature, for being "robust" as well as "receptive of new things".[160]In addition to being politically divisive, Aristia's version ofSaulwas stylistically controversial. Its language was defended with an erudite chronicle by Heliade himself,[161]and was much treasured by the aspiring Moldavian novelist,Constantin Negruzzi.[162]Aristia, who declared himself interested in rendering the language particular to the "pontiffs of poetry",[51]innovated theRomanian lexis.Saulhad a mixture of archaic terms, especially from Christian sermons, and new borrowings from the otherRomance languages.At this stage, Aristia focused on accuracy and precision, and refrained from adhering to Heliade's more heavily Italienized idiom; his version of theRomanian Cyrillic alphabetwas also simplified, with the removal of any superfluous characters.[163]According to Călinescu, the result was still somewhat prolix, and the vocabulary "bizarre", mainly because "Aristia has not mastered Romanian".[51]

Literary historian N. Roman dismissesPrințul românas "confusing and embarrassing verse".[164]In "pompous style", it depicted the minutiae of Bibescu's coronation, and defined Bibescu as the paragon of patriotism, on par withTheseus,Lycurgus of Sparta,Marcus Furius Camillus,andAttila.[165]A fragment suggested the "main direction of princely propaganda", by identifying Bibescu with a 16th-century national hero,Michael the Brave.[166]An unknown Russian chronicler inDas Auslandmagazine ridiculed the poet for "unleash[ing] all his poetic energy on Bibescu's horse", and claimed that this aspect also annoyed the Prince himself.[77]Aristia expected the book to be known and praised by his Moldavian colleagues, to whom he sent free copies.[6]Instead,Prințul românwas "mercilessly" panned[167]by the celebrated Moldavian poet,Vasile Alecsandri,in an 1844 review forPropășirea.It read: "Clap your hands, my fellow Romanians, for at long last, after along, longwait [Alecsandri's italics] that took some thousands of years, you have proven yourselves worthy of receiving an epic poem! [...] This golden age of yours has arrived as an8º tomethat's packed full of wriggled verse and of ideas even more wriggled. "[168]

The first drafts of theIliadin Aristia's interpretation were criticized for their coinage of composite words—ridiculed examples includepedeveloce( "fast-running" ) andbraț-alba( "white-armed" );[169]more such words also appeared in the 1850s version:coiflucerinde( "helmet-shining" ),pedager( "quick-footed" ), andcai-domitoriu( "horse-taming" ).[128]His inventions also included thevocativezee,for "O goddess", in the very first line of the epic. Petre Gheorghe Bârlea describeszeeas a precious contribution, superior to theSlavic-soundingzeițo,which was retained in the version penned in 1920 byGeorge Murnu.He notes that, overall, Aristia "decided to cut off literary Romanian from that vast and heterogeneous field that is everyday language".[170]LinguistLazăr Șăineanulikens the artificial project to that undertaken in 16th-century French literature byDu BartasandLa Pléiade.[169]

Aristia's revisedIliadis viewed as "unintelligible" to more modern readers,[108]"in a language that is new, harmonious, enchanting, but is not Romanian."[171]According to the critic Ioan Duma, Aristia's care in answering his detractors was misdirected, since his translation remained "vacuous";[56]scholarNicolae Bănescualso highlights the issue of Aristia "tortur[ing] language".[172]Călinescu sees Aristia's text as a "masterpiece in extravagance", a "caricature-like answer" to more professional translations byNikolay GnedichandJohann Heinrich Voss.[51]The effort was criticized on such grounds by Heliade himself, who "still preserved his common sense."[173]However, as scholarGheorghe Bogdan-Duicănotes, Aristia's applied talents "did wonders" for advancing the Romanian literary effort.[174]Bârlea defends Aristia against his "many critics", especially those who, likeNicolae Iorga,spoke from "literary pride, having tried, in various takes, their own Homeric translations."[175]

Aristia's efforts in enriching the Romanian lexis were also directed to non-lyrical pursuits, as with his version of Plutarch and its 24-page glossary. The standard proposed here was profusely Italienized, with some Greekcalquesadded.[176]The preface also included a first instance of the wordviaticum,borrowed from Latin in its original meaning, "provision for a journey".[177]Aristia's project in Bible translation may have been inspired by Heliade's earlier attempts. According to Birtz, he refrained from following Heliade's heretical speculation, and was thus deemed palatable by theWallachian Orthodox Church.[178]His overall involvement in Christian literature was touched by additional controversy, particularly regarding its depiction ofLonginusas both a Romanian and the "first Christian". ScholarMihail Kogălniceanuidentified this as a "maniacal" exaggeration which "does not befit a Romanian", and which was prone to make nationalism look ridiculous.[179]

Notes

[edit]- ^Jump up to: abcdeLărgeanu, p. 7

- ^Jump up to: abcdefghijM. M. H., "Cronica. Activitatea folcloristică internațională. Folcloriștii greci despre cercetările noastre de folclor", inRevista de Folclor,Vol. III, Issue 4, 1958, p. 174

- ^Stamatopoulou-Vasilakou, pp. 47–48

- ^Bârlea, p. 17

- ^Jump up to: abcdefConstantin D. Ananescu, "Constantin Aristia — 114 anĭ de la nașterea sa", inAdevĕrul,13 January 1914, p. 1

- ^Jump up to: abcdefghiCălinescu, p. 150

- ^Jump up to: abcdefghijkMaria Protase, "Aristia Costache", in Aurel Sasu (ed.),Dicționarul biografic al literaturii române,Vol. I, p. 421. Pitești:Editura Paralela 45,2004.ISBN973-697-758-7

- ^Jump up to: abcdDumitrescu, p. 15

- ^Minar, p. 6; Ionuț Niculescu, "Familia Caragiale – între adevăr și legendă", inVitraliu,Vol. VII, Issue 13, 1999, p. 4

- ^Dumitrescu, p. 15; Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 321; Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 74; Potra (1990), p. 524; Puchner (2017), p. 285; Stamatopoulou-Vasilakou, p. 48

- ^Puchner (2017), p. 285

- ^Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 53

- ^Berzuc, p. 100; Puchner (2006), p. 93

- ^Călinescu, p. 150; Donatiello, pp. 28, 43; Dumitrescu, p. 15; Ghica & Roman, p. 149; Lărgeanu, p. 7; Potra (1990), p. 524; Puchner (2017), p. 293; Stamatopoulou-Vasilakou, p. 48

- ^Jump up to: abcBerzuc, p. 97

- ^Puchner (2017), p. 293

- ^Birtz, pp. 16, 44; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 270; Lărgeanu, pp. 7–8; Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 74

- ^Puchner (2017), pp. 285–286

- ^Puchner (2017), p. 286

- ^Ghica & Roman, p. 493

- ^Iorga (1921), pp. 272–273. See also Călinescu, p. 150; Lărgeanu, pp. 7–8

- ^Ghica & Roman, p. 173; Iorga (1921), p. 273

- ^Iorga (1921), pp. 75, 362

- ^Puchner (2017), pp. 283, 289

- ^Călinescu, p. 150; Dumitrescu, p. 15; Lărgeanu, p. 8

- ^Donatiello, pp. 28, 34

- ^Jump up to: abcdLărgeanu, p. 8

- ^Ghica & Roman, pp. 12, 149, 255, 348. See also Potra (1990), p. 524

- ^Ghica & Roman, p. 348

- ^Ghica & Roman, pp. 255, 348

- ^Bogdan-Duică, p. 125. See also Călinescu, pp. 64, 140, 149; Dimaet al.,p. 276; Puchner (2017), p. 271

- ^Puchner (2017), p. 271

- ^Donatiello, p. 31

- ^Puchner (2017), p. 283

- ^Bogdan-Duică, p. 90; Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 75

- ^Jump up to: abcdeIosif Hodoșiu,"Foisior'a. Relatiunea dlui Iosif Hodosiu despre teatru in tierile romane", inFederatiunea,Issue 105/1870, pp. 418–419

- ^Nicolae Isar,O istorie a Principatelor Române: de la emancipare politică la Unire, 1769–1859,pp. 12–13. Bucharest: Editura Universitară, 2016.ISBN978-606-28-0443-5

- ^Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 72

- ^Donatiello, pp. 31–32

- ^Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 75. See also Sibechi, pp. 387, 390; Stamatopoulou-Vasilakou, p. 48

- ^Dumitrescu, pp. 14, 15; Potra (1963), p. 87

- ^Potra (1990), pp. 524–525. See also Călinescu, pp. 166, 171; Dimaet al.,pp. 527, 593

- ^Minar, pp. 6–7

- ^Jump up to: abcSibechi, p. 390

- ^Bogdan-Duică, pp. 126–127; Dumitrescu, p. 12; Ghica & Roman, p. 436; Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 321

- ^Berzuc, p. 97; Bogdan-Duică, pp. 127, 172; Călinescu, pp. 150, 267; Dimaet al.,pp. 247, 615; Dumitrescu, pp. 13–16, 173–174; Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 75; Potra (1990), p. 526; Stamatopoulou-Vasilakou, p. 48

- ^Stamatopoulou-Vasilakou, p. 48

- ^Jump up to: abAnca Hațiegan, "Apariția actriței profesioniste: elevele primelor școli românești de muzică și artă dramatică (V)", inVatra,Issues 10–11/2018, p. 151

- ^Dumitrescu, pp. 13–16, 77; Sibechi, p. 390

- ^Potra (1990), p. 527

- ^Jump up to: abcdefgCălinescu, p. 149

- ^Dumitrescu, p. 13

- ^Bogdan-Duică, pp. 117–118, 127; Dimaet al.,pp. 247, 258; Donatiello, pp. 34–37, 43; Ghica & Roman, p. 436

- ^Donatiello, p. 35

- ^Bogdan-Duică, p. 175. See also Călinescu, p. 140; Dimaet al.,p. 276

- ^Jump up to: abcdIoan Duma, "Dări de seamă. Omer: Iliada — trad. de Gh. Murnu", inLuceafărul,Issue 11/1907, p. 233

- ^Jump up to: abAurel Vasiliu, "Bucovina în viața și opera lui M. Eminescu", in Constantin Loghin (ed.),Eminescu și Bucovina,p. 353. Cernăuți: Editura Mitropolitul Silvestru, 1943

- ^Jump up to: abcPapacostea-Danielopolu, p. 75

- ^Donatiello, p. 28; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 270; Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 75

- ^Nicolae Lascu, "Alecu Beldiman traducător al Odiseei", inStudii Literare,Vol. I, 1942, pp. 94–95

- ^Bănescu, pp. 102–103

- ^Donatiello, pp. 35–37, 43

- ^Potra (1990), pp. 527–528

- ^Călinescu, p. 267; Dimaet al.,p. 615

- ^Dumitrescu, pp. 77–78

- ^Bogdan-Duică, p. 133

- ^G. Istrate, "Observații lingvistice pe margineaAlăutei Românești",inAnuar de Lingvistică și Istorie Literară,Vol. XXIII, 1972, p. 158

- ^Călinescu, p. 150; Iorga (1935), pp. 25–27; Pippidi, pp. 339, 344

- ^Constantin Istrati,"Prima școală publică de fete din Bucureștĭ", inLiteratură și Artă Română,Vol. IV, 1899, p. 545

- ^Iorga (1935), pp. 25–27. See also Lărgeanu, p. 7

- ^Marius Gîlea,Despre improvizație,p. 124. Bucharest:UNATC Press,2018.ISBN978-606-8757-42-1

- ^Sibechi, p. 387

- ^Donatiello, pp. 36, 43. See also Călinescu, p. 267

- ^Bogdan-Duică, p. 134

- ^Potra (1963), pp. 150–151

- ^Berzuc, p. 97; Potra (1990), p. 528; Sibechi, pp. 387–388

- ^Jump up to: abBologa, p. 568

- ^Călinescu, p. 150; Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 75

- ^Mihai Eminescu,Articole politice,p. 117. Bucharest:Editura Minerva,1910.OCLC935631395

- ^Isar (1985), p. 198

- ^Berzuc, p. 97; Sibechi, pp. 388–389

- ^Bologa, pp. 567–568; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 270

- ^Birtz, p. 44

- ^Popovici, p. 45

- ^Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 321

- ^Papazoglu & Speteanu, pp. 174, 176

- ^Totu, pp. 20, 29

- ^Constantin D. Aricescu,Capii Revolutiuniĭ Române dela 1848 — judecați de propriele lor acte,pp. 48–52. Bucharest: Typographia Stephan Rassidescu, 1866

- ^Totu, pp. 22, 30

- ^Papazoglu & Speteanu, pp. 176–177

- ^Héliade Radulesco, pp. 116–117

- ^Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 160. See also Călinescu, p. 203

- ^Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 160–161

- ^Totu, p. 30

- ^Jump up to: abPippidi, p. 339

- ^Petre P. Panaitescu,Contribuții la o biografie a lui N. Bălcescu,pp. 77–78. Bucharest:Convorbiri Literare,1924.OCLC876305572

- ^Isar (1985), p. 200

- ^Dimaet al.,p. 334. See also Lărgeanu, p. 8

- ^Constantin Rezachevici, Valeriu Stan, "Memoriile istorice ale colonelului Ion Voinescu I, un izvor inedit privitor la istoria politică a veacului al XIX-lea. Fragmente referitoare la revoluția de la 1848", inRevista de Istorie,Vol. 31, Issue 5, May 1978, p. 847

- ^Héliade Radulesco, pp. 340–341

- ^Popovici, p. 57

- ^Bolintineanu & Roman, pp. VII, 21–22

- ^Bolintineanu & Roman, pp. 24–25; Călinescu, p. 150

- ^Jianu, pp. 100–101

- ^Jianu, p. 101

- ^Bolintineanu & Roman, pp. 26–28

- ^Slăvescuet al.,pp. 96–97

- ^Jump up to: abLăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 270

- ^Jump up to: ab(in Romanian)Andrei Oișteanu,"Din nou despre duelul la români",inRomânia Literară,Issue 37/2005

- ^Pippidi, p. 399

- ^Mircea N. Popa, "'Plini de încredere în înțelepciunea și în simpatiile Dietei de la Frankfurt'", inMagazin Istoric,November 1973, pp. 53, 71

- ^Nicolae Iorga,"Despre Revoluția dela 1848 în Moldova", inMemoriile Secțiunii Istorice,Vol. XX, 1938, pp. 52–53

- ^Fotino, pp. 36–37

- ^Fotino, p. 48

- ^Birtz, p. 16; Dumitrescu, p. 15; Papacostea-Danielopolu, p. 74

- ^Slăvescuet al.,p. 97

- ^Pippidi, pp. 329, 339–340. See also Lărgeanu, p. 8

- ^Pippidi, p. 344

- ^Viorel Faur,Societatea de lectură din Oradea, 1852—1875. Studiu monografic,pp. 235–236. Oradea:Muzeul Țării Crișurilor,1978

- ^Nicolae Iorga,Viața și domnia lui Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, domn al Țerii-Romănești (1849–1856),p. 237.Neamul Românesc:Vălenii de Munte, 1910.OCLC876302354

- ^Jump up to: abCălinescu, p. 150; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 270

- ^Adrian-Silvan Ionescu,"Moștenirea lui Barbu Iscovescu și destinul ei", inMuzeul Național,Vol. XXII, 2010, pp. 52–55

- ^Felecan, p. 53

- ^Ioan Lupu,Dan Berindei,Nestor Camariano,Ovidiu Papadima,Bibliografia analitică a periodicelor românești. Volumul 2: 1851–1858, Partea I,p. 30. Bucharest:Editura Academiei,1970

- ^David, pp. 143–144

- ^Birtz, pp. 16, 25, 84

- ^Birtz, pp. 16–17. See also Conțac, p. 209

- ^Jump up to: abBarbu Lăzăreanu,"Codobatura", inAdevărul,December 14, 1932, p. 1

- ^Bogdan-Duică, p. 306; Călinescu, p. 150

- ^Dumitrescu, pp. 15–16

- ^Tornea, pp. 42–43

- ^Birtz, pp. 16–17; Conțac, pp. 209–210

- ^Nicolae Iorga,"Despre adunarea și tipărirea izvoarelor relative la istoria romînilor. Rolul și misiunea Academiei Romîne", inPrinos lui D. A. Sturdza la la implinirea celor șépte zeci de ani,p. 61. Bucharest:Institutul de Arte Grafice Carol Göbl,1903

- ^Iorga (1935), p. 27

- ^Călinescu, pp. 150–151

- ^Gheorghe Vasilescu, "Din istoricul cartierului Giulești", inBucurești. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie,Vol. IV, 1966, p. 162

- ^Ioan Massoff,Eminescu și teatrul,p. 115. Bucharest:Editura pentru literatură,1964

- ^Dumitru Caracostea,"Arta versificației la Eminescu", inRevista Fundațiilor Regale,Vol. IV, Issue 7, July 1937, p. 58. See also Mănucă, p. 195

- ^"Romani'a", inFederatiunea,Issue 60/1868, p. 236

- ^Mănucă, p. 186

- ^Ștefan Vârgolici,"Retorica pentru tinerimea studioasă de Dimitrie Gusti, ediț. II.", inConvorbiri Literare,Vol. IX, Issue 1, February 1876, p. 444

- ^Lărgeanu, p. 8. See also Dumitrescu, p. 16

- ^"Ce e nou? 'Bene Merenti!'", inFamilia,Issue 21/1876, p. 251

- ^Dumitrescu, pp. 15, 16. See also Călinescu, p. 150

- ^Gheorghe G. Bezviconi,Necropola Capitalei,p. 55. Bucharest:Nicolae Iorga Institute of History,1972

- ^Călinescu, p. 151

- ^Iacob Felix,Raport general asupra igienei publice și asupra Serviciului Sanitar al Capitalei pe anul 1891,pp. 21–22, 29. Bucharest:Lito-tipografia Carol Göbl,1892

- ^Lărgeanu, pp. 7–8

- ^Birtz, pp. 17, 23, 25, 84, 101

- ^Donatiello, pp. 35, 43

- ^Grina-Mihaela Rafailă, "Strada Francmasonă", inBucurești. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie,Vol. XXIII, 2009, p. 131

- ^Eugen Simion,Scriitori români de azi,pp. 170, 174. Bucharest & Chișinău:Editura Litera International,2002.ISBN973-9355-01-3

- ^Adrian Marino,Alexandru Macedonski,"Pietre de Vad. Idei literare macedonskiene", inManuscriptum,Vol. VI, Issue 4, 1975, p. 34

- ^Puchner (2006), p. 88

- ^Papacostea-Danielopolu, pp. 74–75

- ^Donatiello, p. 27

- ^Călinescu, pp. 127–172

- ^Tornea, p. 42

- ^Jump up to: abAlexandre Timoni,Tableau synoptique et pittoresque des littératures les plus remarquables de l'Orient,Vol. III, p. 161. Paris: H. Hubert, 1853

- ^David, p. 144

- ^Bogdan-Duică, pp. 117–118

- ^Călinescu, p. 207

- ^Donatiello, pp. 37, 43

- ^Ghica & Roman, p. 528

- ^Călinescu, p. 150. See also Bologa, pp. 567–568; Pippidi, p. 339

- ^Mirela-Luminița Murgescu, "Figura lui Mihai Viteazul în viziunea elitelor și în literatura didactică (1830—1860)", inRevista Istorică,Vol. 4, Issues 5–6, May–June 1993, p. 542

- ^Ghica & Roman, p. 528. See also Călinescu, pp. 150, 319; Dimaet al.,pp. 417, 483

- ^Garabet Ibrăileanu,"Vasile Alexandri.—Un junimist patruzecioptist", inViața Romînească,Vol. 2, Issue 4, April 1906, p. 55

- ^Jump up to: abLazăr Șăineanu,Istoria filologieĭ române. Cu o privire retrospectivă asupra ultimelor deceniĭ (1870–1895). Studiĭ critice,p. 5. Bucharest:Editura Librăriei Socecŭ & Comp.,1895

- ^Bârlea, pp. 9–10

- ^Bogdan-Duică, pp. 306–307

- ^Bănescu, p. 103

- ^Călinescu, pp. 149–150

- ^Bogdan-Duică, p. 306

- ^Bârlea, p. 10

- ^Despina Ursu, "Glosare de neologisme din perioada 1830–1860", inLimba Română,Vol. XIII, Issue 3, 1964, pp. 259–260

- ^Felecan, pp. 51, 53

- ^Birtz, pp. 17, 41, 44

- ^Mihail Kogălniceanu,Profesie de credință,pp. 255–256. Bucharest & Chișinău:Editura Litera International,2003.ISBN973-7916-30-1

References

[edit]- Nicolae Bănescu,Viața și scrierile Marelui-Vornic Iordache Golescu. Bucăți alese din ineditele sale.Vălenii-de-Munte:Neamul Românesc,1910.

- Petre Gheorghe Bârlea, "Les mots de la colère dans les traductions roumaines des poèmes homériques", inLanguage and Literature – European Landmarks on Identity (Selected Papers of the 13th International Conference of the Faculty of Letters),Issue 18/2016, pp. 8–18.

- Iolanda Berzuc, "Arta interpretării teatrale și societatea românească în secolul al XIX-lea", inStudii și Cercetări de Istoria Artei. Teatru, Muzică, Cinematografie,Vol. 1, 2007, pp. 95–102.

- Mircea Remus Birtz,Considerații asupra unor traduceri biblice românești din sec. XIX–XX.Cluj-Napoca: Editura Napoca Star, 2013.ISBN978-606-690-054-6

- Gheorghe Bogdan-Duică,Istoria literaturii române. Întâii poeți munteni.Cluj:Cluj University& Editura Institutului de Arte Grafice Ardealul, 1923.OCLC28604973

- Dimitrie Bolintineanu(contributor: Ion Roman),Călătorii,Vol. I. Bucharest:Editura Minerva,1968.

- Valeriu Bologa, "Articole mărunte. Un Rus despre literatura română în anul 1844", inDacoromania,Vol. V, 1927–1928, pp. 562–570.

- George Călinescu,Istoria literaturii române de la origini pînă în prezent.Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1986.

- Emanuel Conțac, "Tradiția biblică românească. O prezentare succintă din perspectiva principalelor versiuni românești ale Sfintei Scripturi", inStudii Teologice,Issue 2/2011, pp. 159–245.

- Doina David, "Traducerea în istoria românei literare. Atitudini teoretice caracteristice anilor 1830–1860", inAnalele Universității de Vest din Timișoara. Seria Științe Filologice,Vols. XLII–XLIII, 2004–2005, pp. 137–154.

- Alexandru Dimaand contributors,Istoria literaturii române. II: De la Școala Ardeleană la Junimea.Bucharest:Editura Academiei,1968.

- Federico Donatiello, "Lingua e nazione sulla scena: il teatro di Alfieri, Voltaire e Felice Romani e il processo di modernizzazione della società romena nel XIX secolo", inTransylvanian Review,Vol. XXVI, Supplement 2, 2017, pp. 27–44.

- Horia Dumitrescu,Scriitorul, diplomatul și academicianul Dumitru (Dimitrie) Constantin Ollănescu-Ascanio (1849–1908).Focșani: Editura Pallas, 2014.ISBN978-973-7815-63-7

- Nicolae Felecan, "Noțiunea de 'drum' în limba română", inLimba Română,Issues 1–3/2007, pp. 50–53.

- George Fotino,Din vremea renașterii naționale a țării românești: Boierii Golești. III: 1850–1852.Bucharest:Monitorul Oficial,1939.

- Ion Ghica(contributor: Ion Roman),Opere, I.Bucharest:Editura pentru literatură,1967.OCLC830735698

- J. Héliade Radulesco,Mémoires sur l'histoire de la régénération roumaine, ou Sur les événements de 1848 accomplis en Valachie.Paris: Librairie de la propagande démocratique et sociale européene, 1851.OCLC27958555

- Nicolae Iorga,

- Izvoarele contemporane asupra mișcării lui Tudor Vladimirescu.Bucharest:Librăriile Cartea Românească& Pavel Suru, 1921.OCLC28843327

- "Două documente privitoare la poetul Constantin Aristia—comunicate de dr. Ananescu", inRevista Istorică,Vol. XXI, Issues 1–3, January–March 1935, pp. 25–28.

- Nicolae Isar, "Documentar. Două publicații din timpul revoluției de la 1848", inRevista de Istorie,Vol. 38, Issue 2, February 1985, pp. 196–206.

- Angela Jianu,A Circle of Friends. Romanian Revolutionaries and Political Exile, 1840–1859. Balkan Studies Library, Volume 3.Leiden & Boston:Brill Publishers,2011.ISBN978-90-04-18779-5

- Grigore Lăcusteanu(contributor: Radu Crutzescu),Amintirile colonelului Lăcusteanu. Text integral, editat după manuscris.Iași:Polirom,2015.ISBN978-973-46-4083-6

- Amelia Lărgeanu, "Embaticarii moșiei Grozăvești", inBiblioteca Bucureștilor,Vol. VI, Issue 8, 2003, pp. 7–8.

- Dan Mănucă,Argumente de istorie literară.Iași:Editura Junimea,1978.

- Octav Minar,Caragiale. Omul și opera.Bucharest:Socec & Co.,1913.

- Cornelia Papacostea-Danielopolu, "Les cours de grec dans les écoles roumaines après 1821 (1821—1866)", inRevue des Études Sud-est Européennes,Vol. IX, Issue 1, 1971, pp. 71–90.

- Dimitrie Papazoglu(contributor: Viorel Gh. Speteanu),Istoria fondării orașului București. Istoria începutului orașului București. Călăuza sau conducătorul Bucureștiului.Bucharest: Fundația Culturală Gheorghe Marin Speteanu, 2000.ISBN973-97633-5-9

- Andrei Pippidi,"Repatrierea exilaților după revoluția din 1848 din Țara Românească", inRevista Arhivelor,Issue 2/2008, pp. 328–362.

- Dumitru Popovici,"Santa Cetate" între utopie și poezie.Bucharest: Editura Institutului de Istorie Literară și Folclor, 1935.OCLC924186321

- George Potra,

- Petrache Poenaru, ctitor al învățământului în țara noastră. 1799–1875.Bucharest:Editura științifică,1963.

- Din Bucureștii de ieri,Vol. I. Bucharest: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1990.ISBN973-29-0018-0

- Walter Puchner,

- "The Theatre in South-East Europe in the Wake of Nationalism", inΤετράδια Εργασίας,Vol. 29, 2006, pp. 75–134.

- Greek Theatre between Antiquity and Independence. A History of Reinvention from the Third Century BC to 1830.Cambridge & New York City:Cambridge University Press,2017.ISBN9781107445024

- Gh. Sibechi, "Biografii pașoptiste (III)", inCercetări Istorice,Vol. XII–XIII, 1981–1982, pp. 387–401.

- Victor Slăvescu,Ion Ghica,Ion Ionescu de la Brad,Corespondența între Ion Ionescu de la Brad și Ion Ghica, 1846–1874.Bucharest: Monitorul Oficial, 1943.

- Chrysothemis Stamatopoulou-Vasilakou, "The Greek Communities in the Balkans and Asia Minor and Their Theatrical Activity 1800–1922", inÉtudes Helléniques/Hellenic Studies,Vol. 16, Issue 2, Autumn 2008, pp. 39–63.

- Florin Tornea, "Centenarul nașterii lui C. Nottara. Moștenirea 'Meșterului'", inTeatrul,Vol. IV, Issue 7, July 1959, pp. 42–44.

- Maria Totu,Garda civică din România 1848—1884.Bucharest:Editura Militară,1976.OCLC3016368

- 1800 births

- 1880 deaths

- 19th-century Romanian male actors

- Romanian male stage actors

- Romanian theatre directors

- Romanian theatre managers and producers

- Drama teachers

- Romanian costume designers

- Romanian textbook writers

- Language reformers

- Neoclassical writers

- Romantic poets

- Modern Greek-language writers

- Romanian writers in French

- 19th-century Romanian poets

- Romanian male poets

- 19th-century Romanian dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century Romanian short story writers

- Romanian male short story writers

- Romanian columnists

- Romanian magazine editors

- Romanian magazine founders

- Romanian newspaper editors

- 19th-century Romanian translators

- French–Greek translators

- Greek–Romanian translators

- Italian–Greek translators

- Italian–Romanian translators

- Translators of the Bible into Romanian

- Romanian librarians

- Romanian schoolteachers

- Academic staff of the University of Bucharest

- Male actors from Bucharest

- Writers from Bucharest

- Writers from the Principality of Wallachia

- Eastern Orthodox writers

- Members of the Church of Greece

- Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church

- Members of the Filiki Eteria

- Wallachian people of the Greek War of Independence

- Organizers of the Wallachian Revolution of 1848

- Romanian nationalists

- Romanian monarchists

- Prefects of Bucharest

- Serdari of Wallachia

- 19th-century Romanian civil servants

- 19th-century military personnel of the Principality of Wallachia

- Romanian prisoners and detainees

- Prisoners and detainees of the Ottoman Empire

- Romanian people taken hostage

- People deported from Romania

- Romanian exiles

- Wallachian refugees in the Austrian Empire

- Romanian expatriates in France

- Romanian expatriates in Greece

- Romanian expatriates in Italy

- Expatriates in the Ottoman Empire

- Romanian philanthropists

- Romanian blind people

- Blind educators

- Blind writers

- Blind poets

- Romanian writers with disabilities

- Burials at Sfânta Vineri Cemetery