Counterterrorism

Counterterrorism(alternatively spelled:counter-terrorism), also known asanti-terrorism,relates to the practices,military tactics,techniques, and strategies that governments,law enforcement,businesses, andintelligence agenciesuse to combat or eliminateterrorism.[1]

If an act of terrorism occurs as part of a broaderinsurgency(and insurgency is included in thedefinition of terrorism) then counterterrorism may additionally employcounterinsurgencymeasures. TheUnited States Armed Forcesuses the term "foreign internal defense"for programs that support other countries' attempts to suppress insurgency,lawlessness,orsubversion,or to reduce the conditions under which threats tonational securitymay develop.[2][3][4]

History

[edit]The first counterterrorism body to be formed was the Special Irish Branch of theMetropolitan Police,later renamed theSpecial Branchafter it expanded its scope beyond its original focus onFenianterrorism. Variouslaw enforcement agenciesestablished similar units in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.[5]The first tactical counterterrorist unit wasGSG 9of theGerman Federal Police,formed in response to the 1972Munich massacre.[6]

Counterterrorist forces expanded with the perceived growing threat of terrorism in the late 20th century. After theSeptember 11 attacks,Western governments made counterterrorism efforts a priority. This included more extensive collaboration with foreign governments, shifting tactics involvingred teams,[7]and preventive measures.[8]

Although terrorist attacks affecting Western countries generally receive a disproportionately large share of media attention,[9]most terrorism occurs in less developed countries.[10]Government responses to terrorism, in some cases, tend to lead to substantial unintended consequences,[11][vague]such as what occurred in the above-mentioned Munich massacre.[further explanation needed]

Planning

[edit]Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance

[edit]

Most counterterrorism strategies involve an increase in policing and domesticintelligencegathering. Central techniques includeintercepting communicationsandlocation tracking.New technology has expanded the range ofmilitaryandlaw enforcementoptions for intelligence gathering. Many countries increasingly employfacial recognition systemsin policing.[12][13][14]

Domestic intelligence gathering is sometimes directed to specificethnicor religious groups, which are the sources of political conversy.Mass surveillanceof an entire population raises objections oncivil libertiesgrounds.Domestic terrorists,especiallylone wolves,are often harder to detect because of their citizenship or legal status and ability to stay under the radar.[15]

To select the effective action when terrorism appears to be more of an isolated event, the appropriate government organizations need to understand the source, motivation, methods of preparation, and tactics of terrorist groups. Good intelligence is at the heart of such preparation, as well as a political and social understanding of any grievances that might be solved. Ideally, one gets information from inside the group, a very difficult challenge forhuman intelligenceoperations becauseoperational terrorist cellsare often small, with all members known to one another, perhaps even related.[16]

Counterintelligenceis a great challenge with the security of cell-based systems, since the ideal, but the nearly impossible, goal is to obtain aclandestine sourcewithin the cell. Financial tracking can play a role, as acommunications intercept.However, both of these approaches need to be balanced against legitimate expectations of privacy.[17]

Legal contexts

[edit]In response to the growing legislation.

- The United Kingdom has had counterterrorism legislation in place for more than thirty years. The Prevention of Violence Act 1938 was brought in response to anIrish Republican Army(IRA) campaign of violence under theS-Plan.This act had been allowed to expire in 1953. It was repealed in 1973 to be replaced by thePrevention of Terrorism Acts,a response tothe Troublesin Northern Ireland. From 1974 to 1989, the temporary provisions of the act were renewed annually. Their original counterterrorism legislation was used to predict future IRA attacks and respond accordingly based on their predictions. For example, if British Security Forces attacked, they predicted the IRA would target civilian areas as a response.[18]

- In 2000 the Acts were replaced with the more permanentTerrorism Act 2000,which contained many of their powers, and then thePrevention of Terrorism Act 2005.

- TheAnti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001was formally introduced into the Parliament on November 19, 2001, two months after theSeptember 11, 2001 attacksin the United States. It received royal assent and went into force on December 13, 2001. On December 16, 2004, the Law Lords ruled that Part 4 was incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights. However, under the terms of theHuman Rights Act 1998,it remained in force. ThePrevention of Terrorism Act 2005was drafted to answer the Law Lords ruling and theTerrorism Act 2006creates new offenses related to terrorism, and amends existing ones. The act was drafted in the aftermath of the7 July 2005 London bombingsand, like its predecessors, some of its terms have proven to be highly controversial.

Since 1978 the UK's terrorism laws have been regularly reviewed by a security-clearedIndependent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation,whose often influential reports are submitted to Parliament and published in full.

- U.S. legal issues surrounding this issue include rulings on the domestic employment ofdeadly forceby law enforcement agencies.

- Search and seizure is governed by theFourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

- The U.S. passed thePatriot Actafter the September 11 attacks, as well as a range of other legislation andexecutive ordersrelating to national security.

- TheDepartment of Homeland Securitywas established to consolidate domestic security agencies to coordinate counterterrorism and national response to major natural disasters and accidents.

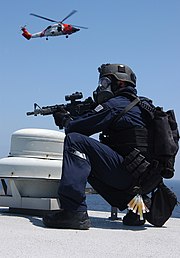

- TheUnited States Coast Guard's mission, only military branch with law enforcement jurisdiction to board and seize"The direct or indirect supply, sale, or transfer of weapons to terrorist organizations violates U.N. Security Resolution 2216 (as extended and renewed by resolutions 2675 and 2707) and international law."[19]

- ThePosse Comitatus Actlimits domestic employment of theUnited States Armyand theUnited States Air Force,requiring Presidential approval before deploying the Army or the Air Force.Department of Defensepolicy also applies this limitation to theUnited States Marine Corpsand theUnited States Navy,because the Posse Comitatus Act does not cover naval services, even though they are federal military forces. The Department of Defense can be employed domestically on Presidential order, as was done during theLos Angeles riots of 1992,Hurricane Katrina,and theBeltway Sniperincidents.

- External or international use of lethal force would require aPresidential finding.

- In February 2017, sources claimed that the Trump administration intends to rename and revamp the U.S. government programCountering Violent Extremism(CVE) to focus solely on Islamist extremism.[20]

- Australia has passed several counterterrorism acts. In 2004, a bill comprising three actsAnti-terrorism Act, 2004, (No 2) and (No 3)was passed. Then Attorney-General,Philip Ruddock,introduced theAnti-terrorism bill, 2004on March 31. He described it as "a bill to strengthen Australia's counter-terrorism laws in a number of respects – a task made more urgent following the recent tragicterrorist bombingsin Spain. "He said that Australia's counterterrorism laws" require review and, where necessary, updating if we are to have a legal framework capable of safeguarding all Australians from the scourge of terrorism. "TheAustralian Anti-Terrorism Act 2005supplemented the powers of the earlier acts. The Australian legislation allows police to detain suspects for up to two weeks without charge and to electronically track suspects for up to a year. TheAustralian Anti-Terrorism Act of 2005included a "shoot-to-kill" clause. In a country with entrenchedliberal democratictraditions, the measures are controversial and have been criticized bycivil libertariansandIslamicgroups.[21]

- Israel monitors a list of designatedterrorist organizationsand has laws forbidding membership in such organizations and funding or helping them.

- On December 14, 2006, theIsraeli Supreme Courtruledtargeted killingswere a permitted form of self-defense.[22]

- In 2016 the IsraeliKnessetpassed a comprehensive law against terrorism, forbidding any kind of terrorism and support of terrorism, and setting severe punishments for terrorists. The law also regulates legal efforts against terrorism.[23]

Human rights

[edit]

One of the primary difficulties of implementing effective counterterrorist measures is the waning of civil liberties and individual privacy that such measures often entail, both for citizens of, and for those detained by states attempting to combat terror.[24]At times, measures designed to tighten security have been seen asabuses of poweror even violations of human rights.[25]

Examples of these problems can include prolonged, incommunicado detention without judicial review or long periods of 'preventive detention';[26]risk of subjecting to torture during the transfer, return and extradition of people between or within countries; and the adoption of security measures that restrain the rights or freedoms of citizens and breach principles of non-discrimination.[27]Examples include:

- In November 2003,Malaysiapassed new counterterrorism laws, widely criticized by local human rights groups for being vague and overbroad. Critics claim that the laws put the fundamental rights of free expression, association, and assembly at risk. Malaysia persisted in holding around 100 alleged militants without trial, including five Malaysian students detained for alleged terrorist activity while studying in Karachi, Pakistan.[27]

- In November 2003, a Canadian-Syrian national, Maher Arar, publicly alleged that he had been tortured in a Syrian prison after being handed over to the Syrian authorities by the U.S.[27]

- In December 2003, Colombia's congress approved legislation that would give the military the power to arrest, tap telephones, and carry out searches without warrants or any previous judicial order.[27]

- Images of torture and ill-treatment of detainees in U.S. custody in Iraq and other locations have encouraged international scrutiny of U.S. operations in the war on terror.[28]

- Hundreds of foreign nationals remain in prolonged indefinite detention without charge or trial in Guantánamo Bay, despite international and U.S. constitutional standards some groups believe outlaw such practices.[28]

- Hundreds of people suspected of connections with theTalibanorAl-Qaedaremain in long-term detention in Pakistan or in U.S.-controlled centers in Afghanistan without trial.[28]

- China has used the "war on terror" to justify its policies in the predominantly MuslimXinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Regionto stifle Uyghur identity.[28]

- In Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Yemen, and other countries, scores of people have been arrested and arbitrarily detained in connection with suspected terrorist acts or links to opposition armed groups.[28]

- Until 2005, eleven men remained in high security detention in the UK under the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001.[28]

- United Nations experts condemned the misuse of counterterrorism powers by the Egyptian authorities following the arrest, detention, and designation of human rights activists Ramy Shaath and Zyad El-Elaimy as terrorists. The two activists were arrested in June 2019, and the first-ever renewal of remand detention for Shaath came for the 21st time in 19 months on 24 January 2021. Experts called it alarming, and demanded the urgent implementation of the Working Group's opinion and removal of the two's names from the "terrorism entities' list.[29]

Many argue that such violations of rights could exacerbate rather than counter the terrorist threat.[27]Human rights activists argue for the crucial role of human rights protection as an intrinsic part to fight against terrorism.[28][30]This suggests, as proponents ofhuman securityhave long argued, that respecting human rights may indeed help us to incur security.Amnesty Internationalincluded a section on confronting terrorism in the recommendations in the Madrid Agenda arising from the Madrid Summit on Democracy and Terrorism (Madrid March 8–11, 2005):

Democratic principles and values are essential tools in the fight against terrorism. Any successful strategy for dealing with terrorism requires terrorists to be isolated. Consequently, the preference must be to treat terrorism as criminal acts to be handled through existing systems of law enforcement and with full respect for human rights and the rule of law. We recommend: (1) taking effective measures to make impunity impossible either for acts of terrorism or for the abuse of human rights in counter-terrorism measures. (2) the incorporation of human rights laws in all anti-terrorism programs and policies of national governments as well as international bodies. "[28]

While international efforts to combat terrorism have focused on the need to enhance cooperation between states, proponents of human rights (as well ashuman security) have suggested that more effort needs to be given to the effective inclusion of human rights protection as a crucial element in that cooperation. They argue that international human rights obligations do not stop at borders, and a failure to respect human rights in one state may undermine its effectiveness in the global effort to cooperate to combat terrorism.[27]

Preemptive neutralization

[edit]Some countries see preemptive attacks as a legitimate strategy. This includes capturing, killing, or disabling suspected terrorists before they can mount an attack. Israel, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Russia have taken this approach, while Western European states generally do not.[citation needed]

Another major method of preemptive neutralization is theinterrogationof known or suspected terrorists to obtain information about specific plots, targets, the identity of other terrorists, whether or not the interrogation subjects himself is guilty of terrorist involvement. Sometimes more extreme methods are used to increasesuggestibility,such assleep deprivationor drugs.[citation needed]Such methods may lead captives to offer false information in an attempt to stop the treatment, or due to the confusion caused by it.[citation needed]In 1978 theEuropean Court of Human Rightsruled in theIreland v. United Kingdomcase thatsuch methodsamounted to a practice ofinhuman and degrading treatment,and that such practices were in breach of theEuropean Convention on Human RightsArticle 3 (art. 3).[citation needed]

Non-military

[edit]

Thehuman securityparadigm outlines a non-military approach that aims to address the enduring underlying inequalities which fuel terrorist activity. Causal factors need to be delineated and measures implemented which allow equal access to resources andsustainabilityfor all people. Such activities empower citizens, providing "freedom from fear" and "freedom from want".[citation needed]

This can take many forms, including the provision of clean drinking water, education, vaccination programs, provision of food and shelter and protection from violence, military or otherwise. Successful human security campaigns have been characterized by the participation of a diverse group of actors, including governments,NGOs,and citizens.[citation needed]

Foreign internal defenseprograms provide outside expert assistance to a threatened government. FID can involve both non-military and military aspects of counterterrorism.[citation needed]

A 2017 study found that "governance and civil society aid is effective in dampening domestic terrorism, but this effect is only present if the recipient country is not experiencing a civil conflict."[31]

Military

[edit]

Terrorism has often been used to justifymilitary interventionin countries where terrorists are said to be based. Similar justifications were used for theU.S. invasion of Afghanistanand thesecond Russian invasion of Chechnya.

Military intervention has not always been successful in stopping or preventing future terrorism, such as during theMalayan Emergency,theMau Mau uprising,and most of the campaigns against theIRAduring theIrish Civil War,theS-Plan,theBorder Campaign,andthe Troublesin Northern Ireland. Although military action can temporarily disrupt a terrorist group's operations temporarily, it sometimes does not end the threat completely.[32]

Repression by the military in itself usually leads to short term victories, but tend to be unsuccessful in the long run (e.g., the French doctrine used in colonialIndochinaandAlgeria[33]), particularly if it is not accompanied by other measures. However, new methods such as those taken inIraqhave yet to be seen as beneficial or ineffectual.[34]

Preparation

[edit]Target hardening

[edit]Whatever the target of terrorists, there are multiple ways of hardening the targets to prevent the terrorists from hitting their mark, or reducing the damage of attacks. One method is to placehostile vehicle mitigationto enforce protective standoff distance outside tall or politically sensitive buildings to preventcar bombings.Another way to reduce the impact of attacks is to design buildings for rapid evacuation.[35]

Aircraft cockpits are kept locked during flights and have reinforced doors, which only the pilots in the cabin are capable of opening. UKrailway stationsremoved their garbage bins in response to theProvisional IRAthreat, as convenient locations for depositing bombs. Scottish stations removed theirs after the7 July 2005 London Bombingsas a precautionary measure. TheMassachusetts Bay Transportation Authoritypurchased bomb-resistant barriers after the September 11 attacks.

Due to frequent shelling of Israel's cities, towns, and settlements byartillery rocketsfrom theGaza Strip(mainly byHamas,but also by other Palestinian factions) andLebanon(mainly byHezbollah), Israel has developed several defensive measures against artillery, rockets, and missiles. These include building abomb shelterin every building and school, but also deployingactive protection systemssuch as theArrow ABM,Iron DomeandDavid's Sling,which intercept the incoming threat in the air.Iron Domehas successfully intercepted hundreds ofQassam rocketsandGrad rocketsfired by Palestinians from the Gaza Strip.[36][37]

A more sophisticated target-hardening approach must consider industrial and other critical industrial infrastructure that could be attacked. Terrorists do not need to import chemical weapons if they can cause a major industrial accident such as theBhopal disasteror theHalifax Explosion.Industrial chemicals in manufacturing, shipping, and storage thus require greater protection, and some efforts are in progress.[38]To put this risk into perspective, the first major lethal chemical attack ofWorld War Iused 160 tons of chlorine; industrial shipments of chlorine, widely used in water purification and the chemical industry, travel in 90- or 55-ton tank cars.[original research?]

To give one more example, theNortheast blackout of 2003demonstrated the vulnerability of the North American electrical grid to natural disasters coupled with inadequate, possibly insecure,SCADA(supervisory control and data acquisition) networks. Part of the vulnerability is due to deregulation, leading to much more interconnection in a grid designed for only occasional power-selling between utilities. A small number of terrorists, attacking critical power facilities when one or more engineers have infiltrated the power control centers, could wreak havoc.[original research?]

Equipping likely targets with containers of pig lard has been used to discourage attacks by suicide bombers. The technique was apparently used on a limited scale by British authorities in the 1940s. The approach stems from the idea that Muslims perpetrating the attack would not want to be "soiled" by the lard in the moment before dying.[39]The idea has been suggested more recently as a deterrent to suicide bombings in Israel.[40]However, the actual effectiveness of this tactic is likely limited. A sympathetic Islamic scholar could issue afatwaproclaiming that a suicide bomber would not be polluted by the swine products.

Command and control

[edit]For a threatened or completed terrorist attack, anIncident Command System(ICS) may be invoked to control the various services that may need to be involved in the response. ICS has varied levels of escalation, such as might be required for multiple incidents in a given area (e.g.2005 London bombingsor the2004 Madrid train bombings), or all the way to aNational Response Planinvocation if national-level resources are needed. For example, a national response might be required for a nuclear, biological, radiological, or significant chemical attack.

Damage mitigation

[edit]Fire departments,perhaps supplemented by public works agencies, utility providers, and heavy construction contractors, are most apt to deal with the physical consequences of an attack.

Local security

[edit]Again under an incident command model, local police can isolate the incident area, reducing confusion, and specialized police units can conduct tactical operations against terrorists, often using specialized counterterrorist tactical units. Bringing in such units will typically involve civil or military authority beyond the local level.

Medical services

[edit]Emergency medical servicesare capable of triaging, treating, and transporting the more severely affected individuals to hospitals, which typically havemass casualtyandtriageplans in place for terrorist attacks.

Public health agencies,from local to the national level, may be designated to deal with identification, and sometimes mitigation, of possible biological attacks, and sometimes chemical or radiologic contamination.

Tactical units

[edit]

Many countries have dedicated counterterrorist units trained to handle terrorist threats. Besides varioussecurity agencies,there arepolice tactical unitswhose role is to directly engage terrorists and prevent terrorist attacks. Such units perform both in preventive actions, hostage rescue, and responding to ongoing attacks. Countries of all sizes can have highly trained counterterrorist teams. Tactics, techniques, and procedures formanhuntingare under constant development.

These units are specially trained inmilitary tacticsand are equipped forclose-quarters combat,with emphasis on stealth and performing the mission with minimal casualties. The units include assault teams,snipers,EODexperts, dog handlers, and intelligence officers. Most of these measures deal with terrorist attacks that affect an area or threaten to do so, or are lengthy situations such asshootoutsand hostage takings that allow the counterterrorist units to assemble and respond; it is harder to deal with shorter incidents such as assassinations or reprisal attacks, due to the short warning time and the quick exfiltration of the assassins.[41]

The majority of counterterrorism operations at the tactical level are conducted by state, federal, and national law enforcement orintelligence agencies.In some countries, the military may be called in as a last resort. For countries whose military is legally permitted to conduct domestic law enforcement operations, this is not an issue, and such counterterrorism operations are conducted by their military.

Counterterrorist operations

[edit]

Some counterterrorist actions of the 20th and 21st centuries are listed below. Seelist of hostage crisesfor a more extended list, including hostage-takings that did not end violently.

| Incident | Main locale | Hostage nationality | Kidnappers /hijackers |

Counterterrorist force | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Sabena Flight 571 | Tel Aviv-Lod International Airport,Israel | Mixed | Black September | Sayeret Matkal | 2 hijackers killed, 1 passenger died from wounds during raid. 2 passengers and 1 commando injured. 2 kidnappers captured. All other 96 passengers rescued. |

| 1972 | Munich massacre | Munich,West Germany | Israeli | Black September | German Federal Border Guard | All hostages murdered; 5 kidnappers and 1 West German police officer killed. 3 kidnappers captured and released. This fatal result was the reason for the foundation of the German special counterterrorism unitGSG9 |

| 1975 | AIA building hostage crisis | AIA building,Kuala Lumpur,Malaysia | Mixed. American and Swedish | Japanese Red Army | Special Actions Unit | All hostages released, all kidnappers flown to Libya. |

| 1976 | Operation Entebbe | Entebbe airport,Uganda | Israelis and Jews. Non-Jewish hostages were released shortly after capture. | PFLP | Sayeret Matkal,Sayeret Tzanhanim, Sayeret Golani | All 7 hijackers, 45 Ugandan troops, 3 hostages, and 1 Israeli soldier were killed. 100 hostages rescued |

| 1977 | Lufthansa Flight 181 | Initially over theMediterranean

Sea,south ofthe French coast; subsequentlyMogadishu International Airport,Somalia |

Mixed | PFLP | GSG 9,Special Air Serviceconsultants | 1 hostage killed before the raid; 3 hijackers killed and 1 captured. 90 hostages rescued. |

| 1980 | Casa Circondariale di TraniPrison riot[citation needed] | Trani,Italy | Italian | Red Brigades | Gruppo di intervento speciale(GIS) | 18 police officers rescued, all terrorists captured. |

| 1980 | Iranian Embassy siege | London, UK | Mostly Iranian but some British | Democratic Revolutionary Movement for the Liberation of Arabistan | Special Air Service | 5 kidnappers killed, 1 kidnapper captured. 1 hostage killed prior to raid, 1 hostage killed by kidnapper during raid; 24 hostages rescued. 1 SAS operative received minor burns. |

| 1979-1981 | Iran hostage crisis | Tehran,Iran | Americans | Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line | United States Army Special Forces,Delta Force,75th Infantry Regiment (Ranger),CIA Special Activities Division,1st Special Operations Wing | 8 US servicemen killed & 4 injured 1 Iranian civilian (alleged by Iranian Army) killed inOperation Eagle Claw.Negotiation finished in 1981. 53 hostages released. |

| 1981 | Garuda Indonesia Flight 206 | Don Mueang Airport,Bangkok,Thailand | Mostly Indonesian, some Europeans/Americans | Komando Jihad | Kopassusassault group,RTAFsecuring perimeter | 5 hijackers killed (2 likely killed extrajudicially after raid),1 Kopassus operative killed, 1 pilot fatally wounded by terrorist, all hostages rescued. |

| 1982 | Operation Winter Harvest | Padua,Italy | American | Red Brigades | U.S. Army Intelligence Support Activity(ISA),Delta ForceandNucleo Operativo Centrale di Sicurezza(NOCS) | Hostage saved, capture of the entire terrorist cell. |

| 1983 | Turkish embassy attack | Lisbon,Portugal | Turkish | Armenian Revolutionary Army | GOE | 5 hijackers, 1 hostage, and 1 police officer killed, 1 hostage and 1 police officer wounded. |

| 1985 | Achille Laurohijacking | MSAchille Laurooff the Egyptian coast | Mixed | Palestine Liberation Organization | U.S. military,Navy SEALsturned over toItalian special forces(Gruppo di intervento speciale) | 1 hostage killed during hijacking, 4 hijackers convicted in Italy |

| 1986 | Pudu Prison siege | Pudu Prison,Kuala Lumpur,Malaysia | Two doctors | Prisoners | Special Actions Unit | 6 kidnappers captured, 2 hostages rescued |

| 1988 | Mothers Bus | Hijacked betweenBeer ShevaandDimona,Israel | 11 passengers | Palestinian Liberation Organization | YAMAM | 3 hijacker killed, 3 hostages killed, 8 hostages rescued |

| 1993 | Indian Airlines Flight 427 | Hijacked between Delhi andSrinagar,India | 141 passengers | Islamic terrorist (Mohammed Yousuf Shah) | National Security Guard | 1 hijacker killed, all hostages rescued. |

| 1994 | Air France Flight 8969 | Marseille,France | Mixed | Armed Islamic Group of Algeria | GIGN | 4 hijackers killed. 3 hostages killed before the raid, 229 hostages rescued |

| 1996 | Japanese embassy hostage crisis | Lima,Peru | Japanese and guests (800+) | Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement | Peruvian militaryandpolicemixed forces | All 14 kidnappers, 1 hostage, and 2 rescuers killed. |

| 1996 | Mapenduma hostage crisis | Mapenduma,Indonesia | Mixed (19 Indonesians, 4 British, 2 Dutch, & 1 German) | Kelly Kwalik'sFree Papua Movement(OPM) Group | Kopassus's SAT-81 Gultor CT Group,Kostrad's Infantry Battalion, Penerbad (Army Aviation) Mixed Forces | 8 kidnappers killed, 2 kidnappers captured. 2 hostages killed by kidnappers, 24 Hostages rescued. 5 Army Operatives killed in helicopter accident. |

| 2000 | Sauk Siege | Perak,Malaysia | Malaysian (2 police officers, 1 soldier and 1 civilian) | Al-Ma'unah | Grup Gerak Khasand 20Pasukan Gerakan Khas,mixed forces | 2 hostages, 2 rescuers, and 1 kidnapper killed. Other 28 kidnappers captured. |

| 2001–2005 | Pankisi Gorge crisis | Pankisi Gorge,Kakheti,Georgia | Mixed,Al-Qaedaand Chechen rebels led byIbn al-Khattab | 2,400 troops, 1,000 police officers | Terrorism threats in the gorge were repressed. | |

| 2002 | Moscow theater hostage crisis | Moscow, Russia | Mixed, mostly Russian (900+) | Special Purpose Islamic Regiment | Spetsnaz | All 39 kidnappers and 129–204 hostages killed. 600–700 hostages freed. |

| 2004 | Beslan school siege | Beslan,North Ossetia-Alania,Russia | Russian | Riyad-us Saliheen | MVD(includingOMON),Russian army(includingSpetsnaz), Russian police (Militsiya) | 334 hostages killed and hundreds wounded. 10–21 rescuers killed. 31 kidnappers killed, 1 captured. |

| 2007 | Siege of Lal Masjid | Islamabad,Pakistan | Students andTehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan | Pakistan ArmyandRangers,Special Service Group | 91 students/militants killed, 50 militants captured. 10 SSG and 1 Ranger killed; 33 SSG, 3 Rangers, 8 soldiers wounded. 204 civilians injured. | |

| 2007 | Kirkuk Hostage Rescue[citation needed] | Kirkuk, Iraq | Turkman child | Islamic State of IraqAl Qaeda | PUK's Kurdistan Regional Government's Counter Terrorism Group | 5 kidnappers arrested, 1 hostage rescued[citation needed] |

| 2008 | Operation Jaque | Colombia | Mixed | Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia | Columbian military | 15 hostages rescued. 2 kidnappers captured |

| 2008 | Operations Dawn | Gulf of Aden,Somalia | Mixed | Somali pirates and militants | PASKALand mixed international forces | Negotiation finished. 80 hostages released. RMN, including PASKAL navy commandos with mixed international forces patrolling the Gulf of Aden during this festive period.[42][43][44] |

| 2008 | 2008 Mumbai attacks | Multiple locations inMumbaicity | Indian Nationals, Foreign tourists | Ajmal Qasab and other Pakistani nationals affiliated to Laskar-e-taiba | National Security Guard,MARCOS,Mumbai Police,Rapid Action Force | 141 Indian civilians, 30 foreigners, 15 police officers, and two NSG commandos were killed. 9 attackers killed, 1 attacker captured. 293 individuals injured |

| 2009 | Maersk Alabama hijacking | Gulf of Aden, Somalia. | 23 crew | Somali pirates | U.S. Navy,SEAL Team Six | 3 kidnappers killed and 1 captured. All hostages rescued. |

| 2009 | 2009 Lahore Attacks | Multiple locations inLahorecity | Pakistan | Lashkar-e-Taiba | Police Commandos,Army Rangers Battalion | March 3, The Sri Lankan cricket team attack – 6 members of the Sri Lankan cricket team were injured, 6 Pakistani police officers and 2 civilians killed.

March 30, the Manawan Police Academy in Lahore attack – 8 gunmen, 8 police personnel and 2 civilians killed, 95 people injured, 4 gunmen captured.[citation needed] |

| 2011 | Operation Dawn of Gulf of Aden | Gulf of Aden,Somalia | Koreans,Myanmar, Indonesian | Somali pirates and militants | Republic of Korea Navy Special Warfare Flotilla(UDT/SEAL) | 4+ kidnappers killed or missing (Jan 18). 8 kidnappers killed, 5 captured. All hostages rescued. |

| 2012 | Lopota Gorge hostage crisis | LopotaGorge,Georgia | Georgians | Ethnic Chechen, Russian, and Georgian militants | Special Operations Center, SOD, KUD,army special forces | 2 KUD members and one special forces corpsman killed, 5 police officers wounded. 11 kidnappers killed, 5 wounded, and 1 captured. All hostages rescued. |

| 2013 | 2013 Lahad Datu standoff | Lahad Datu,Sabah, Malaysia | Malaysians | Royal Security Forces of the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo(Jamalul Kiram III's faction) | Malaysian Armed Forces,Royal Malaysia Police,Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agencyandjoint counterterrorist forces,Philippine Armed Forces | 8 police officers (including 2PGK commandos) and one soldier killed, 12 others wounded. 56 militants killed, 3 wounded, and 149 captured. All hostages rescued. 6 civilians killed and one wounded. |

| 2017 | 2017 Isani flat siege | Isani district,Tbilisi,Georgia | Georgians | Chechen militants | State Security Service of Georgia,police special forces | 3 militants killed, includingAkhmed Chatayev.One special forces officer killed during skirmishes. |

| 2024 | Operation Golden Hand | Rafah,Gaza Strip | Israeli | Hamas | YAMAMandShin Betwith support from theIsrael Defense Forces | 94 palestinian civilians killed, 8 militants killed, all hostages were rescued safely. |

Designing counterterrorist systems

[edit]This section'stone or style may not reflect theencyclopedic toneused on Wikipedia.(June 2021) |

The scope for counterterrorism systems is very large in physical terms and in other dimensions, such as type and degree of terrorist threats, political and diplomatic ramifications, and legal concerns. Ideal counterterrorist systems use technology to enable persistentintelligence,surveillance and reconnaissance missions, and potential actions. Designing such a system-of-systems comprises a major technological project.[45]

A particular design problem for counterterrorist systems is the uncertainty of the future: the threat of terrorism may increase, decrease or remain the same, the type of terrorism and location are difficult to predict, and there are technological uncertainties. A potential solution is to incorporateengineering flexibilityinto system design, allowing for flexibility when new information arrives. Flexibility can be incorporated in the design of a counter-terrorism system in the form of options that can be exercised in the future when new information is available.[45]

Law enforcement

[edit]While some countries with longstanding terrorism problems have law enforcement agencies primarily designed to prevent and respond to terror attacks,[46]in other nations, counterterrorism is a relatively more recent objective of law enforcement agencies.[47][48]

Though somecivil libertariansandcriminal justicescholars have criticized efforts of law enforcement agencies to combat terrorism as futile and expensive[49]or as threats to civil liberties,[49]other scholars have analyzed the most important dimensions of the policing of terrorism as an important dimension of counter-terrorism, especially in the post-9/11 era, and have discussed how police view terrorism as a matter of crime control.[47]Such analyses highlight the civilian police role in counterterrorism next to the military model of awar on terror.[50]

American law enforcement

[edit]

Pursuant to passage of theHomeland Security Act of 2002,federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies began to systemically reorganize.[51][52]Two primary federal agencies, theDepartment of Justice(DOJ) and theDepartment of Homeland Security(DHS), house most of the federal agencies that are prepared to combat domestic and international terrorist attacks. These include theBorder Patrol,theSecret Service,theCoast Guardand theFBI.

Following suit from federal changes pursuant to 9/11, however, most state and local law enforcement agencies began to include a commitment to "fighting terrorism" in their mission statements.[53][54]Local agencies began to establish more patterned lines of communication with federal agencies. Some scholars have doubted the ability of local police to help in the war on terror and suggest their limited manpower is still best utilized by engaging community and targeting street crimes.[49]

While counter-terror measures (most notably heightened airport security, immigrantprofiling[55]and border patrol) have been adapted during the last decade, to enhance counter-terror in law enforcement, there have been remarkable limitations to assessing the actual utility/effectiveness of law enforcement practices that are ostensibly preventative.[56]Thus, while sweeping changes in counterterrorist rhetoric redefined most American post 9/11 law enforcement agencies in theory, it is hard to assess how well such hyperbole has translated into practice.

Inintelligence-led policing(ILP) efforts, the most quantitatively amenable starting point for measuring the effectiveness of any policing strategy (i.e.: Neighborhood Watch, Gun Abatement, Foot Patrols, etc.) is usually to assess total financial costs against clearance rates or arrest rates. Since terrorism is such a rare event phenomena,[57]measuring arrests or clearance rates would be a non-generalizable and ineffective way to test enforcement policy effectiveness. Another methodological problem in assessing counterterrorism efforts in law enforcement hinges on finding operational measures for key concepts in the study ofhomeland security.Both terrorism and homeland security are relatively new concepts for criminologists, and academicians have yet to agree on the matter of how to properly define these ideas in a way that is accessible.

Counterterrorism agencies

[edit]

Military

[edit]Given the nature of operational counterterrorism tasks national military organizations do not generally have dedicated units whose sole responsibility is the prosecution of these tasks. Instead the counterterrorism function is an element of the role, allowing flexibility in their employment, with operations being undertaken in the domestic or international context.

In some cases the legal framework within which they operate prohibits military units conducting operations in the domestic arena;United States Department of Defensepolicy, based on thePosse Comitatus Act,forbids domestic counterterrorism operations by the U.S. military. Units allocated some operational counterterrorism tasks are frequentlyspecial forcesor similar assets.

In cases where military organisations do operate in the domestic context some form of formal handover from the law enforcement community is regularly required, to ensure adherence to the legislative framework and limitations. such as theIranian Embassy siege,the British police formally turned responsibility over to theSpecial Air Servicewhen the situation went beyond police capabilities.

See also

[edit]- Civilian casualty ratio

- Civil defense

- Counterinsurgency

- Counter-IED efforts

- Counterjihad

- Deradicalization

- Explosive detection

- Extrajudicial execution

- Extraordinary rendition

- Fatwa on Terrorism

- Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism

- Industrial antiterrorism

- Informant

- Infrastructure security

- International counter-terrorism operations of Russia

- Irregular warfare

- Manhunt (law enforcement)

- Manhunt (military)

- Paramilitary

- Preventive State

- Security increase

- Sociology of terrorism

- Special Activities Division,Central Intelligence Agency

- Targeted killing

- Terrorism Research Center

- War among the people

References

[edit]- ^Stigall, Dan E.; Miller, Chris; Donnatucci, Lauren (October 7, 2019). "The 2018 National Strategy for Counterterrorism: A Synoptic Overview".American University National Security Law Brief.SSRN3466967.

- ^"Introduction to Foreign Internal Defense"(PDF).U.S. Air Force Doctrine.February 1, 2020.

- ^"Introduction to Foreign Internal Defense"(PDF).Curtis E. Lemay Center for Doctrine Development and Education.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on January 24, 2017.RetrievedJuly 10,2019.

- ^"Differences Between Foreign Internal Defense (FID) and Counter Insurgency (COIN)".SOFREP.

- ^Tim Newburn, Peter Neyroud (2013).Dictionary of Policing.Routledge. p. 262.ISBN9781134011551.

- ^"Conception for the Establishment and Employment of a Border-Guard for Special Police Action (GSG9)"(PDF).September 19, 1972.Archived(PDF)from the original on October 9, 2022.RetrievedSeptember 9,2017.

- ^Shaffer, Ryan (2015). "Counter-Terrorism Intelligence, Policy and Theory Since 9/11".Terrorism and Political Violence.27(2): 368–375.doi:10.1080/09546553.2015.1006097.S2CID145270348.

- ^"Preventive Counter-Terrorism Measures and Non-Discrimination in the European Union: The Need for Systematic Evaluation".The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). July 2, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 6,2016.

- ^"Which Countries' Terrorist Attacks Are Ignored By The U.S. Media?".FiveThirtyEight.2016.

- ^"Trade and Terror: The Impact of Terrorism on Developing Countries".Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.2017.

- ^Sexton, Renard; Wellhausen, Rachel L.; Findley, Michael G. (2019). "How Government Reactions to Violence Worsen Social Welfare: Evidence from Peru".American Journal of Political Science.63(2): 353–367.doi:10.1111/ajps.12415.ISSN1540-5907.S2CID159341592.

- ^Lin, Patrick K. (2021)."How to Save Face & the Fourth Amendment: Developing an Algorithmic Auditing and Accountability Industry for Facial Recognition Technology in Law Enforcement".SSRN Electronic Journal.doi:10.2139/ssrn.4095525.ISSN1556-5068.S2CID248582120.

- ^Garvie, Clare (May 26, 2022),"Face Recognition and the Right to Stay Anonymous",The Cambridge Handbook of Information Technology, Life Sciences and Human Rights,Cambridge University Press, pp. 139–152,doi:10.1017/9781108775038.014,ISBN9781108775038,retrievedAugust 16,2023

- ^"Why facial recognition use is growing amid the Covid-19 pandemic".South China Morning Post.November 18, 2020.RetrievedAugust 16,2023.

- ^"The Challenges of Effective Counterterrorism Intelligence in the 2020s".June 21, 2020.

- ^Feiler, Gil (September 2007)."The Globalization of Terror Funding"(PDF).Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, Bar-Ilan University: 29. Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 74.RetrievedNovember 14,2007.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^"Counter-Terrorism Module 12 Key Issues: Surveillance & Interception".

- ^Gill, Paul; Piazza, James A.; Horgan, John (May 26, 2016)."Counterterrorism Killings and Provisional IRA Bombings, 1970–1998".Terrorism and Political Violence.28(3): 473–496.doi:10.1080/09546553.2016.1155932.S2CID147673041.

- ^"USCENTCOM Seizes Iranian Advanced Conventional Weapons Bound for Houthis".U.S. Central Command.RetrievedJanuary 22,2024.

- ^Exclusive: Trump to focus counter-extremism program solely on Islam – sources,Reuters 2017-02-02

- ^"Proposals to further strengthen Australia s counter-terrorism laws 2005".

- ^Summary of Israeli Supreme Court Ruling on Targeted KillingsArchivedFebruary 23, 2013, at theWayback MachineDecember 14, 2006

- ^"Terror bill passes into law".The Jerusalem Post.June 16, 2016.RetrievedJune 16,2016.

- ^"Accountability and Transparency in the United States' Counter-Terrorism Strategy".The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). January 22, 2015. Archived fromthe originalon October 18, 2017.RetrievedSeptember 6,2016.

- ^"Fighting Terrorism Without Violating Human Rights".HuffPost.March 21, 2016.

- ^de Londras, Detention in the War on Terrorism: Can Human Rights Fight Back? (2011)

- ^abcdefHuman Rights News (2004): "Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism", in the Briefing to the 60th Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights.online

- ^abcdefghAmnesty International (2005): "Counter-terrorism and criminal law in the EU.online

- ^"UN experts call for removal of rights defenders Ramy Shaath and Zyad El-Elaimy from 'terrorism entities' list".OHCHR.RetrievedFebruary 11,2021.

- ^"Preventive Counter-Terrorism Measures and Non-Discrimination in the European Union: The Need for Systematic Evaluation".The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism-The Hague (ICCT). July 2, 2011.RetrievedSeptember 6,2016.

- ^Savun, Burcu; Tirone, Daniel C. (2018). "Foreign Aid as a Counterterrorism Tool – Burcu Savun, Daniel C. Tirone".Journal of Conflict Resolution.62(8): 1607–1635.doi:10.1177/0022002717704952.S2CID158017999.

- ^Pape, Robert A. (2005).Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism.Random House. pp. 237–250.

- ^Trinquier, Roger (1961)."Modern Warfare: A French View of Counterinsurgency".Archived fromthe originalon January 12, 2008.

1964 English translation by Daniel Lee with an Introduction by Bernard B. Fall

- ^Nagl, John A.; Petraeus, David H.; Amos, James F.; Sewall, Sarah (December 2006)."Field Manual 3–24 Counterinsurgency"(PDF).US Department of the Army.RetrievedFebruary 3,2008.

While military manuals rarely show individual authors,David Petraeusis widely described as establishing many of this volume's concepts.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^Ronchi, E. (2015)."Disaster management: Design buildings for rapid evacuation".Nature.528(7582): 333.Bibcode:2015Natur.528..333R.doi:10.1038/528333b.PMID26672544.

- ^Robert Johnson (November 19, 2012)."How Israel Developed Such A Shockingly Effective Rocket Defense System".Business Insider.RetrievedNovember 20,2012.

- ^"IDF's 'David's Sling' missile system used to shoot down rocket barrage".The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com.May 10, 2023.RetrievedMay 10,2023.

- ^Weiss, Eric M. (January 11, 2005)."D.C. Wants Rail Hazmats Banned: S.C. Wreck Renews Fears for Capital".The Washington Post.p. B01.

- ^"Suicide bombing 'pig fat threat".BBC News. February 13, 2004.RetrievedJanuary 2,2010.

- ^"Swine: Secret Weapon Against Islamic Terror?".ArutzSheva.December 9, 2007.

- ^Stathis N. Kalyvas (2004)."The Paradox of Terrorism in Civil Wars"(PDF).Journal of Ethics.8(1): 97–138.doi:10.1023/B:JOET.0000012254.69088.41.S2CID144121872.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on October 11, 2006.RetrievedOctober 1,2006.

- ^Crewmen tell of scary ordealArchivedOctober 8, 2008, at theWayback MachineThe StarSunday October 5, 2008.

- ^No choice but to pay ransomArchivedDecember 5, 2008, at theWayback MachineThe StarMonday September 29, 2008

- ^"Ops Fajar mission accomplished".The Star.October 10, 2008. Archived fromthe originalon October 24, 2008.RetrievedNovember 7,2008.

- ^abBuurman, J.; Zhang, S.; Babovic, V. (2009). "Reducing Risk Through Real Options in Systems Design: The Case of Architecting a Maritime Domain Protection System".Risk Analysis.29(3): 366–379.Bibcode:2009RiskA..29..366B.doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01160.x.PMID19076327.S2CID36370133.

- ^Juergensmeyer, Mark (2000). Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- ^abDeflem, Mathieu. 2010. The Policing of Terrorism: Organizational and Global Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- ^Deflem, Mathieu and Samantha Hauptman. 2013. "Policing International Terrorism." Pp. 64–72 in Globalisation and the Challenge to Criminology, edited by Francis Pakes. London: Routledge.[1]

- ^abcHelms, Ronald; Costanza, S E; Johnson, Nicholas (February 1, 2012). "Crouching tiger or phantom dragon? Examining the discourse on global cyber-terror".Security Journal.25(1): 57–75.doi:10.1057/sj.2011.6.ISSN1743-4645.S2CID154538050.

- ^Michael Bayer. 2010. The Blue Planet: Informal International Police Networks and National Intelligence. Washington, DC: National Intelligence Defense College.[2]

- ^Costanza, S.E.; Kilburn, John C. Jr. (2005). "Symbolic Security, Moral Panic and Public Sentiment: Toward a sociology of Counterterrorism".Journal of Social and Ecological Boundaries.1(2): 106–124.

- ^Deflem, M (2004)."Social Control and the Policing of Terrorism Foundations for a sociology of Counterterrorism".American Sociologist.35(2): 75–92.doi:10.1007/bf02692398.S2CID143868466.

- ^DeLone, Gregory J. 2007. "Law Enforcement Mission Statements Post September 11." Police Quarterly 10(2)

- ^Mathieu Deflem. 2010. The Policing of Terrorism: Organizational and Global Perspectives. New York: Routledge.

- ^Ramirez, D., J. Hoopes, and T.L. Quinlan. 2003 "Defining racial profiling in a post-September 11 world." American Criminal Law Review. 40(3): 1195–1233.

- ^Kilburn, John C. Jr.; Costanza, S.E.; Metchik, Eric; Borgeson, Kevin (2011). "Policing Terror Threats and False Positives: Employing a Signal Detection Model to Examine Changes in National and Local Policing Strategy between 2001–2007".Security Journal.24:19–36.doi:10.1057/sj.2009.7.S2CID153825273.

- ^Kilburn, John C. Jr. and Costanza, S.E. 2009 "Immigration and Homeland Security" published in Battleground: Immigration (Ed: Judith Ann Warner); Greenwood Publishing, Ca.

Further reading

[edit]- Arreguín-Toft, Ivan. "Tunnel at the End of the Light: A Critique of U.S. Counter-terrorist Grand Strategy,"Cambridge Review of International Affairs,Vol. 15, No. 3 (2002), pp. 549–563.

- Ivan Arreguín-Toft, "How to Lose a War on Terror: A Comparative Analysis of a Counterinsurgency Success and Failure," in Jan Ångström and Isabelle Duyvesteyn, Eds.,Understanding Victory and Defeat in Contemporary War(London: Frank Cass, 2007).

- Bakker, Edwin, and Tinka Veldhuis.A Fear Management Approach to Counter-Terrorism(International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, 2012)ArchivedApril 2, 2015, at theWayback Machine

- Barton, Mary S.Counterterrorism between the Wars: An International History, 1919-1937(Oxford University Press, 2020)online book review

- Berger, J.M.Making CVE Work: A Focused Approach Based on Process DisruptionArchivedJuly 28, 2020, at theWayback Machine,(International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, May 2016

- Besenyo, Janos.Low-cost attacks, unnoticeable plots?Overview on the economical character of current terrorism, Strategic Impact (ROMANIA) (ISSN: 1841–5784) (eISSN: 1824–9904) 62/2017: (Issue No. 1) pp. 83–100.

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2020."Responses to Terror: Policing and Countering Terrorism in the Modern Age."In The Handbook of Collective Violence: Current Developments and Understanding, eds. C.A. Ireland, et al. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Deflem, Mathieu, and Stephen Chicoine. 2019."Policing Terrorism."In The Handbook of Social Control, edited by Mathieu Deflem. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Deflem, Mathieu and Shannon McDonough. 2015."The Fear of Counterterrorism: Surveillance and Civil Liberties Since 9/11."Society 52(1):70–79.

- Gagliano Giuseppe,Agitazione sovversiva, guerra psicologica e terrorismo(2010)ISBN978-88-6178-600-4,Uniservice Books.

- Ishmael Jones,The Human Factor: Inside the CIA's Dysfunctional Intelligence Culture(2008, revised 2010)ISBN978-1-59403-382-7,Encounter Books.

- James Mitchell, "Identifying Potential Terrorist Targets" a study in the use of convergence. G2 Whitepaper on terrorism, copyright 2006, G2. Counterterrorism Conference, June 2006, Washington D.C.

- James F. Pastor,"Terrorism and Public Safety Policing:Implications for the Obama Presidency" (2009,ISBN978-1-4398-1580-9,Taylor & Francis).

- Jessica Dorsey, Christophe Paulussen,Boundaries of the Battlefield: A Critical Look at the Legal Paradigms and Rules in Countering Terrorism(International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, 2013)ArchivedOctober 22, 2020, at theWayback Machine

- Judy Kuriansky (Editor), "Terror in the Holy Land: Inside the Anguish of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict" (2006,ISBN0-275-99041-9,Praeger Publishers).

- Lynn Zusman (Editor), "The Law of Counterterrorism"(2012,ISBN978-1-61438-037-5,American Bar Association).* Marc Sageman,Understanding Terror Networks(Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004),ISBN0-8122-3808-7.

- Newton Lee,Counterterrorism and Cybersecurity: Total Information Awareness (Second Edition)(Switzerland:Springer International Publishing,2015),ISBN978-3-319-17243-9.

- Merari, Ariel. "Terrorism as a Strategy in Insurgency,"Terrorism and Political Violence,Vol. 5, No. 4 (Winter 1993), pp. 213–251.

- Sinkkonen, Teemu.Political Responses to Terrorism(Acta Universitatis Tamperensis, 2009),ISBN978-9514478710.

- Vandana, Asthana., "Cross-Border Terrorism in India: Counterterrorism Strategies and Challenges,"ACDIS Occasional Paper(June 2010), Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security (ACDIS), University of Illinois