Croagh Patrick

| Croagh Patrick | |

|---|---|

| Cruach Phádraig 'The Reek' | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 764 m (2,507 ft) |

| Prominence | 639 m (2,096 ft) |

| Listing | P600,Marilyn,Hewitt |

| Coordinates | 53°45′34″N9°39′30″W/ 53.7595°N 9.6584°W |

| Naming | |

| English translation | (Saint)Patrick'sstack |

| Language of name | Irish |

| Geography | |

| OSI/OSNI grid | L906802 |

| Topo map | OSiDiscovery30, 31, 37 or 38 |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike |

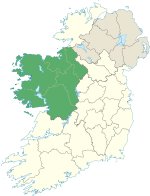

Croagh Patrick(Irish:Cruach Phádraig,meaning '(Saint) Patrick's stack'),[1]nicknamed 'the Reek',[1]is a mountain with a height of 764 m (2,507 ft) and an important site ofpilgrimageinCounty Mayo,Ireland. The mountain has a pyramid-shaped peak and overlooksClew Bay,rising above the village ofMurrisk,several kilometres fromWestport.It has long been seen as aholy mountain.It was the focus of a prehistoricritual landscape,and later became associated withSaint Patrick,who is said to have spent forty days fasting on the summit. There has been a church on the summit since the 5th century; the current church dates to the early 20th century. Croagh Patrick is climbed by thousands of pilgrims every year onReek Sunday,the last Sunday in July, a custom which goes back to at least the Middle Ages.

Croagh Patrick is the fourth-highest mountain in the province ofConnachton theP600 listingafterMweelrea,NephinandBarrclashcame.It is part of a longer east–westridge;the lower westernmost peak is named Ben Goram.

Name

[edit]'Croagh Patrick' comes from the IrishCruach Phádraigmeaning "(Saint)Patrick'sstack ".[1]It is known locally as "the Reek", aHiberno-Englishword for a "rick" or "stack".[2]Previously it was known asCruachán AigleorCruach Aigle,being mentioned by that name in medieval sources such asCath Maige Tuired,[3]Buile Shuibhne,[4]The Metrical Dindshenchas,[5]and theAnnals of Ulsterentry for the year 1113.[6]Cruachánis simply adiminutiveofcruachmeaning "stack" or "peak". Aigle was an old name for the area.[1]TheDindsenchas(lore of places) says that Aigle was a prince of Connacht who was slain by his uncle Cromderg in revenge for his slaying of a woman under Cromderg's care.[7]It is also suggested thatAigleis an alternative form ofaicil,"eagle".[8]

TheMarquess of Sligo,whose seat was nearbyWestport House,bears the titlesBaron Mount EagleandEarl of Altamont( "high mount" ), both deriving from Croagh Patrick.[9]

Historical significance

[edit]Perhaps because of its prominence, itspyramidalquartzitepeak, and the legends associated with it, Croagh Patrick has long been seen as aholy mountain.[10]

Archaeologist Christiaan Corlett writes that the large number ofprehistoricmonuments surrounding and oriented towards Croagh Patrick "suggests that the mountain has been a local spiritual inspiration since at least theNeolithic,and during theBronze Agebecame the focus of an extensiveritual landscape".[11]

A short distance east of the mountain lies theBoheh Stone,an outcrop covered with ancientrock art.There are more than 260 carvings, making it one of the most detailed pieces of ancient rock art in Ireland, and one of only two in the province ofConnacht.In 1987 it was rediscovered that, from the Boheh stone, the setting sun appears to roll down the slope of Croagh Patrick in late April and late August. It is believed the stone was chosen because of this natural phenomenon.[12]Astone rowat Killadangan is aligned with a niche in the mountain where the sun sets on the winter solstice.[13]

Archaeological surveying found remains of an enclosure encircling the mountaintop and dozens of circular huts abutting it, which showed evidence of Bronze Age date.[14]

Tírechán,a native of Connacht, wrote in the 7th century thatSaint Patrickspent forty days on the mountain, likeMosesonMount Sinai.The 9th centuryBethu Phátraicsays that Patrick was harassed by a flock of black demonic birds while on the peak, and he banished them into the hollow of Lugnademon ( "hollow of the demons" ) by ringing his bell. Patrick ended his fast when God gave him the right to judge all the Irish at theLast Judgement,and agreed to spare the land from thefinal desolation.[15][16]A later legend tells how Patrick was tormented by a demonic female serpent named Corra or Caorthannach. Patrick is said to have banished the serpent into Lough Na Corra below the mountain, or into a hollow from which the lake burst forth.[17]

Pilgrimage

[edit]

Archaeologists found that there had been a stonechapelororatoryon the summit since the 5th century.[18]There is reference to a "Teampall Phádraig" (Patrick's Temple) from AD 824, when the Archbishops of Armagh and Tuam disagreed as to who had jurisdiction on the site.[19]A small modern chapel was built on the summit and dedicated on 20 July 1905.

On the last Sunday in July, thousands of pilgrims climb Croagh Patrick in honour of Saint Patrick, andmassesare held at the summit chapel. Some pilgrims climb the mountainbarefoot,as an act ofpenance.[20]Traditionally, pilgrims would perform 'rounding rituals', in which they pray while walkingsunwisearound features on the mountain. Among these are a group of three ancientcairnsknown as Reilig Mhuire (Mary's graveyard),[21]which are likely Bronze Age burial cairns.[22]

FolkloristMáire MacNeillconjectured that the pilgrimage pre-dates Christianity and was originally a ritual associated with the festival ofLughnasadh.[23][24][25]

Today, most pilgrims climb Croagh Patrick from the direction ofMurrisk Abbeyto the north. Originally, most pilgrims climbed the mountain from the east, following the Togher Patrick (Tochár Phádraig) pilgrim path fromBallintubber Abbey.This route is dotted with prehistoric monuments, including the Boheh stone. Until 1970, it was traditional for pilgrims to climb the mountain after sunset. It is possible that this came from a pre-historic tradition of climbing the mountain after viewing the 'rolling sun' phenomenon.[26]TheTochár Phádraigmay have originally been the main route fromCruachan(seat of the Kings of Connacht) to Cruachan Aigle, the original name of Croagh Patrick.[27]TheTochar Phadraigwas revived and reopened as a cross-country pilgrimage tourist trail byPilgrim Paths of Ireland;the 30-kilometre route takes about ten hours.[27]

Local people and organisations point out that the large number of climbers – as many as 40,000 per year – have damaged the mountain by causing erosion which makes the climb more dangerous.[28]

Local stakeholders have made efforts to combat the erosion caused by foot traffic through the creation of a stone path up the mountain, composed of stone from Croagh Patrick and assembled in a dry stone manner.[29]

Leave No Trace Ireland will deliver the Ambassador Training Programme to the selected Ambassadors, working with Mayo County Council to ensure that visitors to Crough Patrick appreciate the importance of preserving the mountain’s distinct natural, cultural and religious heritage through sustainable use. This training programme will also provide guidance on the most effective means for visitors to engage with the mountain, whether local or visiting on how to engage in responsible stewardship of Croagh Patrick. Dogs are not permitted on Croagh Patrick due to animal livestock been present and the threat dog leads pose to other visitors.[30]

Gold discovery

[edit]A seam of gold was discovered in the core of the mountain in the 1980s. Due to local resistance by the Mayo Environmental Group, headed by Paddy Hopkins,Mayo County Councildecided not to allowminingon Croagh Patrick.[31]The name of the Owenwee River (Abhainn Bhuí,yellow river) on the south of the mountain may indicate an ancient awareness of gold deposits in the area andgold panningin the river.[32]

Gallery

[edit]-

Distant view of mountain fromWestport

-

Notice at base about Stations for Catholic climbers, with statue of Saint Patrick

-

Pilgrims climbing the mountain (2007)

-

St. Patrick's Bed at the summit

-

Cairn near summit with view of Clew Bay and Mayo mountains

-

Toilets on the mountain in 1993 (TheSheeffry Hillsin the background)

See also

[edit]- Lists of mountains in Ireland

- List of mountains of the British Isles by height

- List of P600 mountains in the British Isles

- List of Marilyns in the British Isles

- List of Hewitt mountains in England, Wales and Ireland

Bibliography

[edit]- Harry Hughes (2010).Croagh Patrick. A Place of Pilgrimage. A Place of Beauty.O'Brien Press.ISBN9781847171986.

- Leo Morahan (2001).Croagh Patrick, Co. Mayo: archaeology, landscape and people.Westport: Croagh Patrick Archaeological Committee.ISBN0-9536086-3-8.

References

[edit]- ^abcdCruach Phádraig/Croagh Patrick.Placenames Database of Ireland.

- ^New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary,CD edition 1997, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1973, 1993, 1996.

- ^CELT:The Second Battle of Moytura (translation)-Irish

- ^CELT:Buile Shuibhne (translation)-Irish (Cruachán Oighle)

- ^CELT:The Metrical Dindshenchas, 88 Cruachán Aigle (translation)-Irish

- ^CELT:Annals of Ulster 1113 (translation)-Irish

- ^Monaghan, Patricia.The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore.Infobase Publishing, 2014. p.7

- ^"Croagh Patrick, then and now".Mayo Advertiser,9 September 2016.

- ^George Edward Cokayneed.Vicary Gibbs,The Complete Peerage,volume I (1910)p. 113.

- ^Claffey, Patrick."A holy mountain: Croagh Patrick in myth, prehistory and history".The Irish Times,18 November 2016.

- ^Corlett, Christiaan. "The Prehistoric Ritual Landscape of Croagh Patrick, Co Mayo".The Journal of Irish Archaeology,Vol. 9. Wordwell, 1998. pp.9–10

- ^Corlett, p.12

- ^Corlett, p.14

- ^"Scientific evidence suggests Patrick climbed mountain".The Irish Times.Retrieved20 June2021.

- ^Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí(1991).Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition.Prentice Hall Press. p. 358.

- ^Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^Corlett, p.19

- ^McDonald, Michael. "Croagh Patrick." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 21 February 2014

- ^Haggerty, Bridget. "He Came To Mock - But Stayed to Pray", Irish Culture and Customs

- ^"The History of Croagh Patrick from the Croagh Patrick Visitor Centre - Teach na Miasa".www.croagh-patrick.com.Retrieved30 November2016.

- ^Carroll, Michael.Irish Pilgrimage: Holy Wells and Popular Catholic Devotion.JHU Press, 1999. p.38

- ^Corlett, p.11

- ^Harbison, Peter.Pilgrimage in Ireland: The Monuments and the People.Syracuse University Press, 1995. p.70

- ^Monaghan, Patricia.The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore.Infobase Publishing, 2014. p.104

- ^MacNeill, M (1962).The Festival of Lughnasa. A Study of the Survival of the Celtic Festival of the Beginning of the Harvest.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^Corlett, p.17

- ^ab"Tóchar Phádraig Pilgrim Passport".Pilgrim Paths of Ireland.Retrieved2 June2019.

- ^Kieran Cooke (11 October 2015)."The holy mountain that's become too popular".BBC News.Retrieved11 October2015.

- ^Patsy McGarry (31 March 2024)."ThePathway to top of Croagh Patrick almost complete after more than three years of work".The Irish Times.Retrieved1 April2024.

- ^https://www.leavenotraceireland.org/about/croaghpatrickambassador/.

{{cite news}}:Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^"Obituary Paddy Hopkins".The Mayo News.30 July 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 8 March 2018.Retrieved10 September2013.

- ^Corlett, p.18