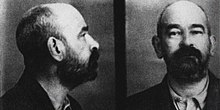

D. S. Mirsky

Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Dmitry Petrovich Svyatopolk-Mirsky 9 September [O.S.22 August] 1890 Giyovka estate,Lyubotin,Russian Empire(now Liubotyn, Ukraine) |

| Died | 7 June 1939(aged 48) Sevvostlag,Soviet Union |

| Pen name | D. S. Mirsky |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Genre | Criticism |

| Subject | Literature |

| This article is part ofa serieson |

| Eurasianism |

|---|

|

D. S. Mirskyis the English pen-name ofDmitry Petrovich Svyatopolk-Mirsky(Russian:Дми́трий Петро́вич Святопо́лк-Ми́рский), often known asPrince Mirsky(9 September [O.S.22 August] 1890 – c. 7 June 1939), a Russian political and literary historian who promoted the knowledge and translations ofRussian literaturein the United Kingdom and ofEnglish literaturein theSoviet Union.He was born inKharkov Governorateand died in a Soviet gulag nearMagadan.

Early life

[edit]He was born Prince Dimitry Petrovich Svyatopolk-Mirsky,[1]scion of theSvyatopolk-Mirsky family,son ofknyazPyotr Dmitrievich Svyatopolk-Mirsky,Imperial RussianMinister of Interior, and Countess EkaterinaBobrinskaya.He relinquished his princely title at an early age. During his school years, he became interested in the poetry ofRussian symbolismand started writing poems himself.

World War I and Civil War

[edit]Mirsky was mobilized in 1914 and saw service in theImperial Russian ArmyduringWorld War I.After theOctober Revolutionhe joined theWhite movementas a member ofDenikin's staff. After the defeat of the White forces he fled to Poland in 1920.

London

[edit]Mirsky emigrated toGreat Britainin 1921. While teaching Russian literature at theUniversity of London,Mirsky published his landmark studyA History of Russian Literature: From Its Beginnings to 1880.Vladimir Nabokovhas called it "the best history of Russian literature in any language including Russian".[2]This work was followed with theContemporary Russian Literature, 1881–1925,. Mirsky was a founding member of theEurasianist movementand the chief editor of the periodicalEurasia,his own views gradually evolving towardMarxism.He also is usually credited with coining the termNational Bolshevism.In 1931, he joined theCommunist Party of Great Britainand askedMaxim Gorkyif he could procure his pardon by Soviet authorities. The permission to return to theUSSRwas granted him in 1932. On seeing him off to Russia,Virginia Woolfwrote in her diary that "soon there'll be a bullet through your head".[3]

Return to Russia

[edit]

Mirsky returned to Russia in September 1932.[4]Five years later, duringthe Great Purge,Mirsky was arrested by theNKVD.Mirsky's arrest may have been caused by a chance meeting with his friend the British historianE. H. Carrwho was visiting the Soviet Union in 1937.[5]Carr stumbled into Prince Mirsky on the streets of Leningrad (modern Saint Petersburg, Russia), and despite Prince Mirsky's best efforts to pretend not to know him, Carr persuaded his old friend to have lunch with him.[6]Since this was at the height of theYezhovshchina,and any Soviet citizen who had any unauthorised contact with a foreigner was likely to be regarded as a spy, the NKVD arrested Mirsky as a British spy.[6]In April 1937, he was denounced in the journalLiteraturnaya Gazetaas a "filthyWrangelistandWhite Guardofficer ".[7]He died in one of thegulaglabour camps near Magadan in June 1939 and was buried on the 7th of that month.[3]He wasrehabilitatedin 1962. Although hismagnum opuswas eventually published in Russia, Mirsky's reputation in his native country remains sparse.

Korney Chukovskygives a lively portrait of Mirsky in his diary entry for 27 January 1935:

I liked him enormously: the vast erudition, the sincerity, the literary talent, the ludicrous beard and ludicrous bald spot, the suit which, though made in England, hung loosely on him, shabby and threadbare, the way he had of coming out with a sympathetic ee-ee-ee (like a guttural piglet squeal) after each sentence you uttered—it was all so amusing and endearing. Though he had very little money—he's a staunch democrat—he did inherit his well-born ancestors' gourmandise. His stomach will be the ruin of him. Every day he leaves his wretched excuse for a cap and overcoat with the concierge and goes into the luxurious restaurant [of the Hotel National in Moscow], spending no less than forty rubles on a meal (since he drinks as well as eats) plus four to tip the waiter and one to tip the concierge.[8]

Criticism

[edit]Malcolm Muggeridge,who met Mirsky after his return to the USSR, apparently met one of the author's critics, a French correspondent to Russia named Luciani, who had this to say of Mirsky: "Mirsky had pulled off the unusual feat of managing to be a parasite under three regimes — as a prince under Czarism, as a professor under Capitalism, and as an homme-de-lettres under Communism." On the other hand, Muggeridge himself said that he was "glad to be his protégé."[9]

George Orwellwas highly critical ofThe Intelligentsia of Great Britain[10]butTariq Alihad a more favourable assessment of this book.[11]

Selected publications

[edit]- Anthology of Russian poetry(1924)

- Modern Russian Literature(1925)

- Pushkin(1926)

- Contemporary Russian Literature, 1881–1925.New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1926. Archived fromthe originalon 2021-10-01.(viaGoogle Books).

- A History of Russian Literature: From the Earliest Times to the Death of Dostoyevsky (1881).New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1927.Reprinted together with 1926 work asA History of Russian Literature.London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949;Reprint:Evanston, Il: Northwestern University Press, 1999.

- A History of Russia(1928)'

- Lenin(London: Holme Press, 1931).

- Russia: A Social History(1931)

- The Intelligentsia of Great Britain(1935), originally in Russian, translated by the author to English

- Anthology of Modern English Poetry(1937) in Russian, published during Mirsky's arrest without acknowledgment of his authorship

References

[edit]- ^"The New Criterion".newcriterion.com.Retrieved2024-11-26.

- ^Gerald Stanton Smith (2000).D.S. Mirsky. A Russian-English Life, 1890-1939.Oxford University Press. p. 295.ISBN978-0-19-816006-9.

- ^abAscherson, Neal (8 March 2001)."Baleful Smile of the Crocodile".London Review of Books.23(5): 9–10.

- ^Roberts, I.W. (1991)History of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, 1915-1990.London: School of Slavonic and East European Studies. p. 29.ISBN978-0903425230

- ^Jonathan Haslam,The Vices of Integrity, E.H. Carr, 1892–1982(London; New York: Verso, 1999), p. 76.

- ^abHaslam,The Vices of Integrity,p. 76.

- ^Conquest, R (1971).The Great Terror.Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. p. 446.

- ^Kornei Chukovsky,Diary, 1901-1969(Yale University Press, 2005:ISBN0-300-10611-4), p. 313.

- ^Muggeridge, Malcolm Tread Softly, for you Tread on My JokesISBN 0002118041 p. 33

- ^Orwell, GeorgeThe Road to Wigan Pier

- ^Ali, TariqThe Coming British Revolution

Further reading

[edit]- Gerald Stanton Smith.D. S. Mirsky: A Russian-English Life, 1890–1939.Oxford University Press: 2000 (ISBN0-19-816006-2).

- Nina Lavroukine et Leonid Tchertkov,D. S. Mirsky: profil critique et bibliographique,Paris, Intitut d'Études Slaves, 1980, 110 pages, 6 planches hors-texte (ISBN2-7204-0164-1). (French language)

External links

[edit]- 1890 births

- 1939 deaths

- People from Liubotyn

- People from Valkovsky Uyezd

- Nobility from the Russian Empire

- National Bolsheviks

- Eurasianists

- Russian male poets

- Russian philologists

- Russian literary historians

- Russian literary critics

- 20th-century Russian poets

- Soviet literary historians

- Soviet male writers

- 20th-century Russian male writers

- Academics of the University of London

- 20th-century Russian journalists

- 20th-century philologists

- Russian Marxist writers

- Communist Party of Great Britain members

- Great Purge victims from Russia