Tao

| Part ofa serieson |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Tao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | Đạo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | way | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | đạo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | Đạo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 도 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | Đạo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | Đạo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | どう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English | /daʊ/DOW,/taʊ/TOW | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In variousChinese religionsandphilosophies,theTaoorDao[note 1]is the natural lessons of the universe that one's intuition must discern to realize the potential for individual wisdom and spiritual growth, as conceived in the context ofEast Asian philosophy,religion,and related traditions. This seeing of life cannot be grasped as a concept. Rather, it is seen through actual living experience of one's everyday being. Its name derives from aChinese characterwith meanings including 'way', 'path', 'road', and sometimes 'doctrine' or 'principle'.[1]

In theTao Te Ching,Laoziexplains that the Tao is not a name for a thing, but the underlying natural order of the universe whose ultimate essence is difficult to circumscribe because it is non-conceptual yet evident in one's being of aliveness. The Tao is "eternally nameless" and should be distinguished from the countless named things that are considered to be its manifestations, the reality of life before its descriptions of it.

Description and uses of the concept

[edit]

The word "Tao" has a variety of meanings in both the ancient and modern Chinese language. Aside from its purely prosaic use meaning road, channel, path, principle, or similar,[2]the word has acquired a variety of differing and often confusing metaphorical, philosophical, and religious uses. In most belief systems, the word is used symbolically in its sense of "way" as the right or proper way of existence, or in the context of ongoing practices of attainment or of the full coming into being, or the state of enlightenment or spiritual perfection that is the outcome of such practices.[3]

Some scholars make sharp distinctions between the moral or ethical usage of the word "Tao" that is prominent inConfucianismand religious Taoism and the more metaphysical usage of the term used in philosophical Taoism and most forms ofMahayana Buddhism;[4]others maintain that these are not separate usages or meanings, seeing them as mutually inclusive and compatible approaches to defining the principle.[5]The original use of the term was as a form ofpraxisrather than theory—a term used as a convention to refer to something that otherwise cannot be discussed in words—and early writings such as theTao Te ChingandI Chingmake pains to distinguish betweenconceptions ofthe Tao (sometimes referred to as "named Tao" ) and the Tao itself (the "unnamed Tao" ), which cannot be expressed or understood in language.[note 2][note 3][6]Liu Da asserts that the Tao is properly understood as an experiential and evolving concept and that there are not only cultural and religious differences in the interpretation of the Tao but personal differences that reflect the character of individual practitioners.[7]

The Tao can be roughly thought of as the "flow of the universe", or as some essence or pattern behind the natural world that keeps the Universe balanced and ordered.[8]It is related toqi,the essential energy of action and existence. The Tao is a non-dualistic principle—it is the greater whole from which all the individual elements of the Universe derive.Catherine Kellerconsiders it similar to thenegative theologyof Western scholars,[9]but the Tao is rarely an object of direct worship, being treated more like theHinduconcepts ofkarma,dharma,orṚtathan as a divine object.[10]The Tao is more commonly expressed in the relationship betweenwu(void or emptiness, in the sense ofwuji) and the natural, dynamic balance between opposites, leading to its central principle ofwu wei(inaction or inexertion).

The Tao is usually described in terms of elements of nature, and in particular, as similar to water.[11][12]Like water it is undifferentiated, endlessly self-replenishing, soft and quiet but immensely powerful, and impassively generous.[note 4]TheSong dynastypainterChen Rongpopularized theanalogywith his paintingNine Dragons.[11]

Much of Taoist philosophy centers on the cyclical continuity of the natural world and its contrast to the linear, goal-oriented actions of human beings, as well as the perception that the Tao is "the source of all being, in which life and death are the same."[14]

In all its uses, the Tao is considered to have ineffable qualities that prevent it from being defined or expressed in words. It can, however, beknownorexperienced,and its principles (which can be discerned by observing nature) can be followed or practiced. Much of East Asian philosophical writing focuses on the value of adhering to the principles of the Tao and the various consequences of failing to do so.

The Tao was shared with Confucianism,Chan BuddhismandZen,and more broadly throughout East Asian philosophy and religion in general. In Taoism, Chinese Buddhism, and Confucianism, the object of spiritual practice is to "become one with the Tao" (Tao Te Ching) or to harmonize one's will with nature (cf.Stoicism) to achieve 'effortless action'. This involves meditative and moral practices. Important in this respect is the Taoist concept ofde('virtue'). In Confucianism and religious forms of Taoism, these are often explicitly moral/ethical arguments about proper behavior, while Buddhism and more philosophical forms of Taoism usually refer to the natural and mercurial outcomes of action (comparable to karma). The Tao is intrinsically related to the concepts ofyin and yang,where every action creates counter-actions as unavoidable movements within manifestations of the Tao, and proper practice variously involves accepting, conforming to, or working with these natural developments.

In Taoism and Confucianism, the Tao was sometimes traditionally seen as a "transcendent power that blesses" that can "express itself directly" through various ways, but most often shows itself through the speech, movement, or traditional ritual of a "prophet, priest, or king."[15]Tao can serve as a life energy instead ofqiin some Taoist belief systems.[16]

De

[edit]De(Đức;'power'', 'virtue'', 'integrity') is the term generally used to refer to proper adherence to the Tao.Deis the active living or cultivation of the way.[17]Particular things (things with names) that manifest from the Tao have their own inner nature that they follow in accordance with the Tao, and the following of this inner nature isDe.Wu wei,or 'naturalness', is contingent on understanding and conforming to this inner nature, which is interpreted variously from a personal, individual nature to a more generalized notion of human nature within the greater Universe.[18]

Historically, the concept of De differed significantly between Taoists and Confucianists. Confucianism was largely a moral system emphasizing the values of humaneness, righteousness, and filial duty, and so conceived De in terms of obedience to rigorously defined and codified social rules. Taoists took a broader, more naturalistic, more metaphysical view on the relationship between humankind and the Universe and considered social rules to be at best a derivative reflection of the natural and spontaneous interactions between people and at worst calcified structure that inhibited naturalness and created conflict. This led to some philosophical and political conflicts between Taoists and Confucians. Several sections of the works attributed toZhuang Zhouare dedicated to critiques of the failures of Confucianism.

Interpretations

[edit]Taoism

[edit]The translatorArthur Waleyobserved that

[Tao] means a road, path, way; and hence, the way in which one does something; method, doctrine, principle. The Way of Heaven, for example, is ruthless; when autumn comes 'no leaf is spared because of its beauty, no flower because of its fragrance'. The Way of Man means, among other things, procreation; and eunuchs are said to be 'far from the Way of Man'.Chu Taois 'the way to be a monarch', i.e. the art of ruling. Each school of philosophy has itstao,its doctrine of the way in which life should be ordered. Finally in a particular school of philosophy whose followers came to be called Taoists,taomeant 'the way the universe works'; and ultimately something very like God, in the more abstract and philosophical sense of that term.[19]

"Tao" gives Taoism its name in English, in both its philosophical and religious forms. The Tao is the fundamental and central concept of these schools of thought. Taoism perceives the Tao as a natural order underlying the substance and activity of the Universe. Language and the "naming" of the Tao is regarded negatively in Taoism; the Tao fundamentally exists and operates outside the realm of differentiation and linguistic constraints.[20]

There is no single orthodox Taoist view of the Tao. All forms of Taoism center around Tao and De, but there is a broad variety of distinct interpretations among sects and even individuals in the same sect. Despite this diversity, there are some clear, common patterns and trends in Taoism and its branches.[21]

The diversity of Taoist interpretations of the Tao can be seen across four texts representative of major streams of thought in Taoism. All four texts are used in modern Taoism with varying acceptance and emphasis among sects. TheTao Te Chingis the oldest text and representative of a speculative and philosophical approach to the Tao. TheDaotilunis an eighth centuryexegesisof theTao Te Ching,written from a well-educated and religious viewpoint that represents the traditional, scholarly perspective. The devotional perspective of the Tao is expressed in theQingjing Jing,aliturgical textthat was originally composed during theHan dynastyand is used as ahymnalin religious Taoism, especially amongeremites.TheZhuangziuses literary devices such as tales, allegories, and narratives to relate the Tao to the reader, illustrating a metaphorical method of viewing and expressing the Tao.[22]

The forms and variations of religious Taoism are incredibly diverse. They integrate a broad spectrum of academic, ritualistic, supernatural, devotional, literary, and folk practices with a multitude of results. Buddhism and Confucianism particularly affected the way many sects of Taoism framed, approached, and perceived the Tao. The multitudinous branches of religious Taoism accordingly regard the Tao, and interpret writings about it, in innumerable ways. Thus, outside of a few broad similarities, it is difficult to provide an accurate yet clear summary of their interpretation of the Tao.[23]

A central tenet in most varieties of religious Taoism is that the Tao is ever-present, but must be manifested, cultivated, and/or perfected to be realized. It is the source of the Universe, and the seed of its primordial purity resides in all things. Breathing exercises, according to some Taoists, allowed one to absorb "parts of the universe."[24]Incense and certain minerals were seen as representing the greater universe as well, and breathing them in could create similar effects.[citation needed]The manifestation of the Tao isde,which rectifies and invigorates the world with the Tao's radiance.[21]

Alternatively, philosophical Taoism regards the Tao as a non-religious concept; it is not a deity to be worshiped, nor is it a mystical Absolute in the religious sense of the Hindubrahman.Joseph Wu remarked of this conception of the Tao, "Dao is not religiously available; nor is it even religiously relevant." The writings of Laozi and Zhuangzi are tinged with esoteric tones and approachhumanismandnaturalismas paradoxes.[25]In contrast to the esotericism typically found in religious systems, the Tao is not transcendent to the self, nor is mystical attainment an escape from the world in philosophical Taoism. The self steeped in the Tao is the self grounded in its place within the natural Universe. A person dwelling within the Tao excels in themselves and their activities.[26]

However, this distinction is complicated byhermeneuticdifficulties in the categorization of Taoist schools, sects, and movements.[27]

Some Taoists believe the Tao is an entity that can "take on human form" to perform its goals.[28]

The Tao represents human harmony with the universe and even more phenomena in the world and nature.

Confucianism

[edit]The Tao ofConfuciuscan be translated as 'truth'. Confucianism regards the Way, or Truth, as concordant with a particular approach to life, politics, and tradition. It is held as equally necessary and well regarded asdeandren('compassion', 'humanity'). Confucius presents a humanistic Tao. He only rarely speaks of the 'Way of Heaven'. The early Confucian philosopherXunziexplicitly noted this contrast. Though he acknowledged the existence and celestial importance of the Way of Heaven, he insisted that the Tao principally concerns human affairs.[29]

As a formal religious concept in Confucianism, Tao is the Absolute toward which the faithful move. InZhongyong(The Doctrine of the Mean), harmony with the Absolute is the equivalent to integrity and sincerity. TheGreat Learningexpands on this concept explaining that the Way illuminates virtue, improves the people, and resides within the purest morality. During theTang dynasty,Han Yufurther formalized and defined Confucian beliefs as anapologeticresponse to Buddhism. He emphasized the ethics of the Way. He explicitly paired "Tao" and "De", focusing on humane nature and righteousness. He also framed and elaborated on a "tradition of the Tao" in order to reject the traditions of Buddhism.[29]

Ancestors and theMandate of Heavenwere thought to emanate from the Tao, especially during theSong dynasty.[30]

Buddhism

[edit]Buddhism first started to spread in China during the first century AD and was experiencing a golden age of growth and maturation by the fourth century AD. Hundreds of collections ofPaliandSanskrittexts were translated into Chinese by Buddhist monks within a short period of time.Dhyanawas translated asThiền;chán],and later as "zen", giving Zen Buddhism its name. The use of Chinese concepts, such as the Tao, that were close to Buddhist ideas and terms helped spread the religion and make it more amenable to the Chinese people. However, the differences between the Sanskrit and Chinese terminology led to some initial misunderstandings and the eventual development of Buddhism in East Asia as a distinct entity. As part of this process, many Chinese words introduced their rich semantic and philosophical associations into Buddhism, including the use of "Tao" for central concepts and tenets of Buddhism.[31]

Pai-chang Huai-hai told a student who was grappling with difficult portions ofsuttas,"Take up words in order to manifest meaning and you'll obtain 'meaning'. Cut off words and meaning is emptiness. Emptiness is the Tao. The Tao is cutting off words and speech." Zen Buddhists regard the Tao as synonymous with both the Buddhist Path and the results of it, theNoble Eightfold PathandBuddhist enlightenment.Pai-chang's statement plays upon this usage in the context of the fluid and varied Chinese usage of "Tao". Words and meanings are used to refer to rituals and practices. The "emptiness" refers to the Buddhist concept ofsunyata.Finding the Tao and Buddha-nature is not simply a matter of formulations, but an active response to theFour Noble Truthsthat cannot be fully expressed or conveyed in words and concrete associations. The use of "Tao" in this context refers to the literal "way" of Buddhism, the return to the universal source,dharma,proper meditation, andnirvana,among other associations. "Tao" is commonly used in this fashion by Chinese Buddhists, heavy with associations and nuanced meanings.[32]

Neo-Confucianism

[edit]During theSong dynasty,neo-Confucians regarded the Tao as the purestthing-in-itself.Shao Yongregarded the Tao as the origin of heaven, earth, and everything within them. In contrast,Zhang Zaipresented a vitalistic Tao that was the fundamental component or effect of qi, the motive energy behind life and the world. A number of later scholars adopted this interpretation, such asTai Chenduring theQing dynasty.[29]

Zhu Xi,Cheng Ho,andCheng Yiperceived the Tao in the context ofli('principle') andt'ien li('principle of Heaven').Cheng Haoregarded the fundamental matter ofli,and thus the Tao, to be humaneness. Developing compassion, altruism, and other humane virtues is following of the Way.Cheng Yifollowed this interpretation, elaborating on this perspective of the Tao through teachings about interactions between yin and yang, the cultivation and preservation of life, and the axiom of a morally just universe.[29]

On the whole, the Tao is equated with totality.Wang Fuzhiexpressed the Tao as thetaiji,or 'great ultimate', as well as the road leading to it. Nothing exists apart from the Principle of Heaven in Neo-Confucianism. The Way is contained within all things. Thus, the religious life is not an elite or special journey for Neo-Confucians. The normal, mundane life is the path that leads to the Absolute, because the Absolute is contained within the mundane objects and events of daily life.[29]

Chinese folklore

[edit]Yayu, the son ofZhulongwho was reincarnated on Earth as a violent hybrid between a bull, a tiger, and adragon,was allowed to go to an afterlife that was known as "the place beyond the Tao".[33]This shows that some Chinesefolk storytellingandmythologicaltraditions had very differing interpretations of the Tao between each other and orthodox religious practices.

Christianity

[edit]Noted Christian authorC.S. Lewisused the word Tao to describe "the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, the kind of thing the Universe is and the kind of things we are."[34]He asserted that every religion and philosophy contains foundations of universal ethics as an attempt to line up with the Tao—the way mankind was designed to be. In Lewis's thinking,Godcreated the Tao and fully displayed it through the person ofJesus Christ.

Similarly, Eastern OrthodoxhegumenDamascene (Christensen), a pupil of noted monastic and scholar of East Asian religionsSeraphim Rose,identifiedlogoswith the Tao. Damascene published a full commented translation of theTao Te Chingunder the titleChrist the Eternal Tao.[35]

In some Chinese translations of the New Testament, the wordλόγος(logos) is translated asĐạo,in passages such asJohn1:1, indicating that the translators considered the concept of Tao to be somewhat equivalent to the Hellenic concept oflogosinPlatonismand Christianity.[36]

Linguistic aspects

[edit]The Chinese characterĐạois highly polysemous: its historical alternate pronunciation asdǎopossessed an additional connotation of 'guide'. The history of the character includes details of orthography and semantics, as well as a possible Proto-Indo-European etymology, in addition to more recent loaning into English and other world languages.

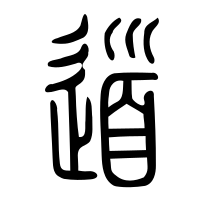

Orthography

[edit]"Tao" is written with the Chinese characterĐạousing bothtraditionalandsimplifiedcharacters. The traditional graphical interpretation ofĐạodates back to theShuowen Jiezidictionary published in 121 CE, which describes it as a rare "compound ideogram" or "ideographic compound".According to theShuowen Jiezi,Đạocombines the 'go' radicalSước(a variant ofSước) withThủ;'head'. This construction signified a "head going" or "leading the way".

"Tao" is graphically distinguished between its earliest nominal meaning of 'way', 'road', 'path', and the later verbal sense of 'say'. It should also be contrasted withĐạo;'lead the way'', 'guide'', 'conduct'', 'direct'. The simplified characterĐạoforĐạohasTị;'6th of the 12Earthly Branches' in place ofĐạo.

The earliest written forms of "Tao" arebronzeware scriptandseal scriptcharacters from theZhou dynasty(1045–256 BCE) bronzes and writings. These ancient forms more clearly depict theThủ;'head' element as hair above a face. Some variants interchange the 'go' radicalSướcwithHành;'go'', 'road', with the original bronze "crossroads" depiction written in the seal character with twoXíchandXúc;'footprints'.

Bronze scripts forĐạooccasionally include an element ofThủ;'hand' orThốn;'thumb'', 'hand', which occurs inĐạo;'lead'. The linguistPeter A. Boodbergexplained,

This "taowith the hand element "is usually identified with the modern characterĐạotao<d'ôg,'to lead,', 'guide', 'conduct', and considered to be aderivativeor verbal cognate of the nountao,"way," "path." The evidence just summarized would indicate rather that "taowith the hand "is but avariantof the basictaoand that the word itself combined both nominal and verbal aspects of the etymon. This is supported by textual examples of the use of the primarytaoin the verbal sense "to lead" (e. g.,Analects1.5; 2.8) and seriously undermines the unspoken assumption implied in the common translation of Tao as "way" that the concept is essentially a nominal one. Tao would seem, then, to be etymologically a more dynamic concept than we have made it translation-wise. It would be more appropriately rendered by "lead way" and "lode" ( "way," "course," "journey," "leading," "guidance"; cf. "lodestone" and "lodestar" ), the somewhat obsolescent deverbal noun from "to lead."[37]

These ConfucianAnalectscitations ofdaoverbally meaning 'to guide', 'to lead' are: "The Master said, 'In guiding a state of a thousand chariots, approach your duties with reverence and be trustworthy in what you say" and "The Master said, 'Guide them by edicts, keep them in line with punishments, and the common people will stay out of trouble but will have no sense of shame."[38]

Phonology

[edit]In modernStandard Chinese,Đạo's two primary pronunciations aretonallydifferentiated between falling tonedào;'way', 'path' and dipping tonedǎo;'guide', 'lead' (usually written asĐạo).

Besides the common specificationsĐạo;dào;'way' andĐạo;dǎo(with variantĐạo;'guide'),Đạohas a rare additional pronunciation with the level tone,dāo,seen in the regionalchengyuThần thần đạo đạo;shénshendāodāo;'odd', 'bizarre', areduplicationofĐạoandThần;shén;'spirit', 'god' from northeast China.

InMiddle Chinese(c. 6th–10th centuries CE)tone namecategories,ĐạoandĐạowereKhứ thanh;qùshēng;'departing tone' andThượng thanh;shǎngshēng;'rising tone'.Historical linguistshave reconstructedMCĐạo;'way' andĐạo;'guide' asd'âu-andd'âu(Bernhard Karlgren),[39]dauanddau[40]daw'anddawh,[41]dawXanddaws(William H. Baxter),[42]anddâuBanddâuC.[43]

InOld Chinese(c. 7th–3rd centuries BCE) pronunciations, reconstructions forĐạoandĐạoare*d'ôg(Karlgren),*dəw(Zhou),*dəgwxand*dəgwh,[44]*luʔ,[42]and*lûʔand*lûh.[43]

Semantics

[edit]The wordĐạohas many meanings. For example, theHanyu Da Zidiandictionary defines 39 meanings forĐạo;dàoand 6 forĐạo;dǎo.[45]

John DeFrancis's Chinese-English dictionary gives twelve meanings forĐạo;dào,three forĐạo;dǎo,and one forĐạo;dāo.Note that brackets clarify abbreviations and ellipsis marks omitted usage examples.

2dàoĐạoN. [noun] road; path ◆M. [nominalmeasure word] ① (for rivers/topics/etc.) ② (for a course (of food); a streak (of light); etc.) ◆V. [verb] ① say; speak; talk (introducing direct quote, novel style)... ② think; suppose ◆B.F. [bound form,bound morpheme] ① channel ② way; reason; principle ③ doctrine ④ Daoism ⑤ line ⑥〈hist.〉 [history] ⑦ district; circuit canal; passage; tube ⑧ say (polite words)... See also4dǎo,4dāo

4dǎoĐạo / đạo [ đạo /-B.F. [bound form] ① guide; lead... ② transmit; conduct... ③ instruct; direct...

4dāoĐạoinshénshendāodāo...Thần thần đạo đạoR.F. [reduplicatedform] 〈topo.〉[non-Mandarin form] odd; fantastic; bizarre[46]

Dao,starting from theSong dynasty,also referred to an ideal inChinese landscape paintingsthat artists sought to live up to by portraying "nature scenes" that reflected "the harmony of man with his surroundings."[47]

Etymology

[edit]The etymological linguistic origins ofdao"way; path" depend upon its Old Chinese pronunciation, which scholars have tentatively reconstructed as *d'ôg,*dəgwx,*dəw,*luʔ,and *lûʔ.

Boodberg noted that theshouThủ"head" phonetic in thedaoĐạocharacter was not merely phonetic but "etymonic", analogous with Englishto headmeaning "to lead" and "to tend in a certain direction," "ahead," "headway".

Paronomastically,taois equated with its homonymĐạotao<d'ôg,"to trample," "tread," and from that point of view it is nothing more than a "treadway," "headtread," or "foretread"; it is also occasionally associated with a near synonym (and possible cognate)Địchti<d'iôk,"follow a road," "go along," "lead," "direct"; "pursue the right path"; a term with definite ethical overtones and a graph with an exceedingly interesting phonetic,Doyu<djôg,""to proceed from. "The reappearance of C162 [Sước] "walk" intiwith the support of C157 [⻊] "foot" intao,"to trample," "tread," should perhaps serve us as a warning not to overemphasize the headworking functions implied intaoin preference to those of the lower extremities.[48]

Victor H. Mairproposes a connection withProto-Indo-Europeandrogh,supported by numerouscognatesinIndo-European languages,as well as semantically similarSemiticArabicandHebrewwords.

The archaic pronunciation of Tao sounded approximately likedrogordorg.This links it to the Proto-Indo-European rootdrogh(to run along) and Indo-Europeandhorg(way, movement). Related words in a few modern Indo-European languages are Russiandoroga(way, road), Polishdroga(way, road), Czechdráha(way, track), Serbo-Croatiandraga(path through a valley), and Norwegian dialectdrog(trail of animals; valley)..... The nearest Sanskrit (Old Indian) cognates to Tao (drog) aredhrajas(course, motion) anddhraj(course). The most closely related English words are "track" and "trek", while "trail" and "tract" are derived from other cognate Indo-European roots. Following the Way, then, is like going on a cosmic trek. Even more unexpected than the panoply of Indo-European cognates for Tao (drog) is the Hebrew rootd-r-gfor the same word and Arabict-r-q,which yields words meaning "track, path, way, way of doing things" and is important in Islamic philosophical discourse.[49]

Axel Schuessler's etymological dictionary presents two possibilities for the tonalmorphologyofdàoĐạo"road; way; method" < Middle ChinesedâuB< Old Chinese *lûʔanddàoĐạoorĐạo"to go along; bring along; conduct; explain; talk about" < MiddledâuC< Old *lûh.[50]EitherdàoĐạo"the thing which is doing the conducting" is a Tone B (shangshengThượng thanh"rising tone" ) "endoactive noun" derivation fromdàoĐạo"conduct", ordàoĐạois a Later Old Chinese (Warring States period) "general tone C" (qushengKhứ thanh"departing tone" ) derivation fromdàoĐạo"way".[51]For a possible etymological connection, Schuessler notes the ancientFangyandictionary definesyu< *lokhDụandlu< *luDuas EasternQi Statedialectal words meaningdào< *lûʔĐạo"road".

Other languages

[edit]Many languages have borrowed and adapted "Tao" as aloanword.

InChinese,this characterĐạois pronounced asCantonesedou6and Hokkianto7.InSino-Xeniclanguages,Đạois pronounced asJapanesedō,tō,ormichi;Koreandoorto;andVietnameseđạo.

Since 1982, when theInternational Organization for StandardizationadoptedPinyinas the standardromanization of Chinese,many Western languages have changed from spelling this loanwordtaoin national systems (e.g., FrenchEFEO Chinese transcriptionand EnglishWade–Giles) todaoin Pinyin.

Thetao/dao"the way"English word of Chinese originhas three meanings, according to theOxford English Dictionary.

1. a.In Taoism, an absolute entity which is the source of the universe; the way in which this absolute entity functions.

1. b.=Taoism,taoist

2.In Confucianism and in extended uses, the way to be followed, the right conduct; doctrine or method.

The earliest recorded usages wereTao(1736),Tau(1747),Taou(1831), andDao(1971).

The term "Taoist priest"(Đạo sĩ;Dàoshì), was used already by the JesuitsMatteo RicciandNicolas Trigaultin theirDe Christiana expeditione apud Sinas,rendered asTausuin the original Latin edition (1615),[note 5]andTausain an early English translation published bySamuel Purchas(1625).[note 6]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Chinese:Đạo;pinyin:dào()

- ^Tao Te Ching,Chapter 1. "It is from the unnamed Tao

That Heaven and Earth sprang;

The named is but

The Mother of the ten thousand creatures. " - ^I Ching,Ta Chuan(Great Treatise). "The kind man discovers it and calls it kind;

the wise man discovers it and calls it wise;

the common people use it every day

and are not aware of it. " - ^Water is soft and flexible, yet possesses an immense power to overcome obstacles and alter landscapes, even carving canyons with its slow and steady persistence. It is viewed as a reflection of, or close in action to, the Tao. The Tao is often expressed as a sea or flood that cannot be dammed or denied. It flows around and over obstacles like water, setting an example for those who wish to live in accord with it.[13]

- ^De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu,Book One, Chapter 10, p. 125. Quote: "sectarii quidamTausuvocant ". Chinese gloss inPasquale M. d' Elia,Matteo Ricci.Fonti ricciane: documenti originali concernenti Matteo Ricci e la storia delle prime relazioni tra l'Europa e la Cina (1579-1615),Libreria dello Stato, 1942; can be foundby searching for "tausu".Louis J. Gallagher(China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci;1953), apparently has a typo (Taufuinstead ofTausu) in thetextof his translation of this line (p. 102), andTausiin the index (p. 615)

- ^A discourse of the Kingdome of China, taken out of Ricius and Trigautius, containing the countrey, people, government, religion, rites, sects, characters, studies, arts, acts; and a Map of China added, drawne out of one there made with Annotations for the understanding thereof(excerpts fromDe Christiana expeditione apud Sinas,in English translation) inPurchas his Pilgrimes,Volume XII, p. 461 (1625). Quote: "... Lauzu... left no Bookes of his Opinion, nor seemes to have intended any new Sect, but certaine Sectaries, called Tausa, made him the head of their sect after his death..." Can be found in thefull text of "Hakluytus posthumus"on archive.org.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^Zai (2015),p.[page needed].

- ^DeFrancis (1996),p. 113.

- ^LaFargue (1992),pp. 245–247.

- ^Chan (1963),p. 136.

- ^Hansen (2000),p. 206.

- ^Liu (1981),pp. 1–3.

- ^Liu (1981),pp. 2–3.

- ^Cane (2002),p. 13.

- ^Keller (2003),p. 289.

- ^LaFargue (1994),p. 283.

- ^abCarlson et al. (2010),p. 704.

- ^Jian-guang (2019),pp. 754, 759.

- ^Ch'eng & Cheng (1991),pp. 175–177.

- ^Wright (2006),p. 365.

- ^Carlson et al. (2010),p. 730.

- ^"Taoism".education.nationalgeographic.org.Retrieved2024-05-29.

- ^Maspero (1981),p. 32.

- ^Bodde & Fung (1997),pp. 99–101.

- ^Waley (1958),p.[page needed].

- ^Kohn (1993),p. 11.

- ^abKohn (1993),pp. 11–12.

- ^Kohn (1993),p. 12.

- ^Fowler (2005),pp. 5–7.

- ^"Daoism".Encarta.Microsoft.Archived fromthe originalon 2009-10-28.

- ^Moeller (2006),pp. 133–145.

- ^Fowler (2005),pp. 5–6.

- ^Mair (2001),p. 174.

- ^Stark (2007),p. 259.

- ^abcdeTaylor & Choy (2005),p. 589.

- ^Harl (2023),p. 272.

- ^Dumoulin (2005),pp. 63–65.

- ^Hershock (1996),pp. 67–70.

- ^Ni (2023),p. 168.

- ^Lewis, C.S.The Abolition of Man.p. 18.

- ^Damascene (2012),p.[page needed].

- ^Zheng (2017),p.187.

- ^Boodberg (1957),p. 599.

- ^Lau (1979),p. 59, 1.5; p. 63, 2.8.

- ^Karlgren (1957),p.[page needed].

- ^Zhou (1972),p.[page needed].

- ^Pulleyblank (1991),p. 248.

- ^abBaxter (1992),pp. 753.

- ^abSchuessler (2007),p.[page needed].

- ^Li (1971),p.[page needed].

- ^Hanyu Da Zidian(1989),pp. 3864–3866.

- ^DeFrancis (2003),pp. 172, 829.

- ^Meyer (1994),p. 96.

- ^Boodberg (1957),p. 602.

- ^Mair (1990),p. 132.

- ^Schuessler (2007),p. 207.

- ^Schuessler (2007),pp. 48–41.

Works cited

[edit]- Baxter, William H.(1992).A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology.Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.ISBN978-3-110-12324-1.

- Bodde, Derk; Fung, Yu-Lan (1997).A short history of Chinese philosophy.Simon and Schuster.ISBN0-684-83634-3.

- Boodberg, Peter A. (1957). "Philological Notes on Chapter One of theLao Tzu".Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies.20(3/4): 598–618.doi:10.2307/2718364.JSTOR2718364.

- Cane, Eulalio Paul (2002).Harmony: Radical Taoism Gently Applied.Trafford Publishing.ISBN1-4122-4778-0.

- Carlson, Kathie; Flanagin, Michael N.; Martin, Kathleen; Martin, Mary E.; Mendelsohn, John; Rodgers, Priscilla Young; Ronnberg, Ami; Salman, Sherry; Wesley, Deborah A. (2010). Arm, Karen; Ueda, Kako; Thulin, Anne; Langerak, Allison; Kiley, Timothy Gus; Wolff, Mary (eds.).The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images.Köln:Taschen.ISBN978-3-8365-1448-4.

- Chang, Stephen T. (1985).The Great Tao.Tao Publishing, imprint of Tao Longevity.ISBN0-942196-01-5.

- Ch'eng, Chung-Ying; Cheng, Zhongying (1991).New dimensions of Confucian and Neo-Confucian philosophy.SUNY Press.ISBN0-7914-0283-5.

- Chan, Wing-tsit (1963).A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy.Princeton.ISBN0-691-01964-9.

- Damascene, Hieromonk (2012).Christ the Eternal Tao(6th ed.). Valaam Books.

- DeFrancis, John, ed. (1996).ABC Chinese-English Dictionary: Alphabetically Based Computerized (ABC Chinese Dictionary).University of Hawaii Press.ISBN0-8248-1744-3.

- DeFrancis, John, ed. (2003).ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary.University of Hawaii Press.

- Dumoulin, Henrik (2005).Zen Buddhism: a History: India and China.Translated by Heisig, James; Knitter, Paul. World Wisdom.ISBN0-941532-89-5.

- Fowler, Jeaneane (2005).An introduction to the philosophy and religion of Taoism: pathways to immortality.Sussex Academic Press.ISBN1-84519-085-8.

- Hansen, Chad D. (2000).A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-513419-2.

- Hanyu Da Zidian(in Chinese). Vol. 6. Wuhan: Hubei Cishu Chubanshe. 1989.ISBN978-7-5403-0022-7.

- Harl, Kenneth W.(2023).Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilization.United States:Hanover Square Press.ISBN978-1-335-42927-8.

- Hershock, Peter (1996).Liberating intimacy: enlightenment and social virtuosity in Ch'an Buddhism.SUNY Press.ISBN0-7914-2981-4.

- Jian-guang, Wang (December 2019)."Water Philosophy in Ancient Society of China: Connotation, Representation, and Influence"(PDF).Philosophy Study.9(12): 750–760.

- Karlgren, Bernhard(1957).Grammata Serica Recensa.Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.

- Keller, Catherine (2003).The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming.Routledge.ISBN0-415-25648-8.

- Kirkland, Russell (2004).Taoism: The Enduring Tradition.Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-26321-4.

- Kohn, Livia (1993).The Taoist experience.SUNY Press.ISBN0-7914-1579-1.

- Komjathy, Louis (2008).Handbooks for Daoist Practice.Hong Kong: Yuen Yuen Institute.

- LaFargue, Michael (1994).Tao and Method: A Reasoned Approach to the Tao Te Ching.SUNY Press.ISBN0-7914-1601-1.

- LaFargue, Michael (1992).The tao of the Tao te ching: a translation and commentary.SUNY Press.ISBN0-7914-0986-4.

- Lau (1979).The Analects (Lun yu).Translated by Lau, D. C. Penguin.

- Li, Fanggui(1971). "Shanggu yin yanjiu"Thượng cổ âm nghiên cứu.Tsinghua Journal of Chinese Studies(in Chinese).9:1–61.

- Liu, Da (1981).The Tao and Chinese culture.Taylor & Francis.ISBN0-7100-0841-4.

- Mair, Victor H. (1990).Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way, by Lao Tzu; an entirely new translation based on the recently discovered Ma-wang-tui manuscripts.Bantam Books.

- Mair, Victor H. (2001).The Columbia History of Chinese Literature.Columbia University Press.ISBN0-231-10984-9.

- Martinson, Paul Varo (1987).A theology of world religions: Interpreting God, self, and world in Semitic, Indian, and Chinese thought.Augsburg Publishing House.ISBN0-8066-2253-9.

- Maspero, Henri (1981).Taoism and Chinese Religion.Translated by Kierman, Frank A. Jr. University of Massachusetts Press.ISBN0-87023-308-4.

- Meyer, Milton Walter (1994).China: A Concise History(2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland:Littlefield Adams Quality Paperbacks.ISBN978-0-8476-7953-9.

- Moeller, Hans-Georg (2006).The Philosophy of the Daodejing.Columbia University Press.ISBN0-231-13679-X.

- Ni, Xueting C. (2023).Chinese Myths: From Cosmology and Folklore to Gods and Immortals.London: Amber Books.ISBN978-1-83886-263-3.

- Pulleyblank, E.G.(1991).Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin.UBC Press.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007).ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese.University of Hawaii Press.ISBN978-0-8248-2975-9.

- Sharot, Stephen (2001).A Comparative Sociology of World Religions: virtuosos, priests, and popular religion.New York: NYU Press.ISBN0-8147-9805-5.

- Stark, Rodney(2007).Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief(1st ed.). New York:HarperOne.ISBN978-0-06-117389-9.

- Sterckx, Roel (2019).Chinese Thought. From Confucius to Cook Ding.London: Penguin.

- Taylor, Rodney Leon; Choy, Howard Yuen Fung (2005).The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Confucianism, Volume 2: N-Z.Rosen Publishing Group.ISBN0-8239-4081-0.

- Waley, Arthur(1958).The way and its power: a study of the Tao tê ching and its place in Chinese thought.Grove Press.ISBN0-8021-5085-3.

- Watts, Alan Wilson (1977).Tao: The Watercourse Waywith Al Chung-liang Huang.Pantheon.ISBN0-394-73311-8.

- Wright, Edmund, ed. (2006).The Desk Encyclopedia of World History.New York:Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-7394-7809-7.

- Zai, J. (2015).Taoism and Science: Cosmology, Evolution, Morality, Health and more.Ultravisum.ISBN978-0-9808425-5-5.

- Zheng, Yangwen, ed. (2017).Sinicizing Christianity.BRILL.ISBN978-90-04-33038-2.

- Zhou Fagao ( chu pháp cao ) (1972). "Shanggu Hanyu he Han-Zangyu"Thượng cổ hán ngữ hòa hán tàng ngữ.Journal of the Institute of Chinese Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong(in Chinese).5:159–244.

Further reading

[edit]- Translation of the Tao te Ching by Derek Lin

- Translation of the Dao de Jing by James Legge

- Legge translation of the Tao Teh Kingat Project Gutenberg

- Feng, Gia-Fu & Jane English (translators). 1972.Laozi/Dao De Jing.New York: Vintage Books.

- Komjathy, Louis.Handbooks for Daoist Practice.10 vols. Hong Kong: Yuen Yuen Institute, 2008.

- Mitchell, Stephen (translator). 1988.Tao Te Ching: A New English Version.New York: Harper & Row.

- Robinet, Isabelle; Brooks, Phyllis; Robinet, Isabelle (1997).Taoism: growth of a religion.Stanford University Press.ISBN978-0-8047-2839-3.

- Sterckx, Roel.Chinese Thought. From Confucius to Cook Ding.London: Penguin, 2019.

- Dao entry from Center for Daoist Studies

- The Tao of Physics,Fritjof Capra, 1975