Doom(1993 video game)

| Doom | |

|---|---|

Cover art byDon Ivan Punchatzfeaturing theDoomguy | |

| Developer(s) | id Software |

| Publisher(s) | id Software |

| Designer(s) | |

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | |

| Composer(s) | Bobby Prince[a] |

| Series | Doom |

| Engine | Doomengine[b] |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | December 10, 1993

|

| Genre(s) | First-person shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player,multiplayer |

Doomis afirst-person shootergame developed and published byid Software.Released on December 10, 1993, forDOS,it is the first installment in theDoomfranchise.The playerassumes the roleof aspace marine,later unofficially referred to asDoomguy,fighting through hordes of undead humans and invadingdemons.The game begins on themoons of Marsand finishes inhell,with the player traversing each level to find its exit or defeat itsfinal boss.It is an early example of3D graphicsin video games, and has enemies and objects as 2D images, a technique sometimes referred to as2.5Dgraphics.

Doomwas the third major independent release by id Software, afterCommander Keen(1990–1991) andWolfenstein 3D(1992). In May 1992, id started developing a darker game focused on fighting demons with technology, using a new 3Dgame enginefrom the lead programmer,John Carmack.The designerTom Hallinitially wrote a science fiction plot, but he and most of the story were removed from the project, with the final game featuring an action-heavy design byJohn RomeroandSandy Petersen.Id publishedDoomas a set of three episodes under thesharewaremodel, marketing the full game by releasing the first episode free. A retail version with an additional episode was published in 1995 byGT InteractiveasThe Ultimate Doom.

Doomwas a critical and commercial success, earning a reputation asone of the bestand most influential video games of all time. It sold an estimated 3.5 million copies by 1999, and up to 20 million people are estimated to have played it within two years of launch. It has been termed the "father" of first-person shooters and is regarded as one of the most important games in the genre. It has been cited by video game historians as shifting the direction and public perception of the medium as a whole, as well as sparking the rise of online games and communities. It led to an array of imitators andclones,as well as a robustmoddingscene and the birth ofspeedrunningas a community. Its high level ofgraphic violenceled to controversy from a range of groups.Doomhas been portedto a variety of platforms both officially and unofficially and has been followed by several games in the series, includingDoom II(1994),Doom 64(1997),Doom 3(2004),Doom(2016),Doom Eternal(2020), andDoom: The Dark Ages(2025), as well as the filmsDoom(2005) andDoom: Annihilation(2019).

Gameplay

[edit]

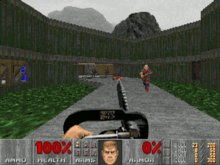

Doomis afirst-person shooterpresented with3D graphics.While the environment is shown in a 3D perspective, the enemies and objects are instead 2Dspritesrendered at fixed angles, a technique sometimes referred to as2.5Dgraphics orbillboarding.[2]In thesingle-playercampaign mode, the player controls an unnamedspace marine—later unofficially termed "Doomguy"—through military bases on themoons of Marsand inhell.[3]To finish a level, the player must traverse through labyrinthine areas to reach a marked exit room. Levels are grouped into named episodes, with the final level of each focusing on aboss fight.[4]

While traversing the levels, the player must fight a variety of enemies, includingdemonsandpossessedundeadhumans. Enemies often appear in large groups. The fivedifficulty levelsadjust the number of enemies and amount of damage they do, with enemies moving and attacking faster than normal on the hardest difficulty setting.[4]The monsters have simple behavior: they move toward their opponent if they see or hear them, and attack by biting, clawing, or using magic abilities such as fireballs.[5]

The player must manage supplies of ammunition,health,and armor while traversing the levels. The player can find weapons and ammunition throughout the levels or can collect them from dead enemies, including a pistol, ashotgun,achainsaw,aplasma rifle,and theBFG 9000.The player also encounters pits oftoxic waste,ceilings that lower and crush objects, and locked doors requiring a collectablekeycardor a remote switch.[6]Power-upsincludehealthor armor points, a mapping computer,partial invisibility,aradiation suitagainst toxic waste, invulnerability, or a super-strong meleeberserkerstatus.Cheat codesallow the player to unlock all weapons, walk through walls, or become invulnerable.[7][8]

Twomultiplayermodes are playable over a network:cooperative,in which two to four players team up to complete the main campaign, anddeathmatch,in which two to four players compete to kill the other players' characters as many times as possible.[9][10]Multiplayer was initially only playable over local networks, but a four-playeronline multiplayermode was made available one year after launch through theDWANGOservice.[10][11]

Plot

[edit]Doomis divided into three episodes, each containing about nine levels: "Knee-Deep in the Dead", "The Shores of Hell", and "Inferno". A fourth episode, "Thy Flesh Consumed", was added in an expanded version,The Ultimate Doom,released two years afterDoom.The campaign contains very few plot elements, with a minimal story presented mostly through the instruction manual and text descriptions between episodes.[12]

In the future, an unnamed marine is posted to a dead-end assignment onMarsafter assaulting a superior officer who ordered his unit to fire on civilians. The Union Aerospace Corporation, which operates radioactive waste facilities there, allows the military to conduct secretteleportationexperiments that turn deadly. A base onPhobosurgently requests military support, whileDeimosdisappears entirely, and the marine joins a combat force to secure Phobos. He waits at the perimeter as ordered while the entire assault team is wiped out. With no way off the moon, and armed with only a pistol, he enters the base intent on revenge.[13]

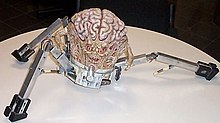

In "Knee-Deep in the Dead", the marine fights demons and possessed humans in the military and waste facilities on Phobos. The episode ends with the marine defeating two powerful Barons of Hell guarding a teleporter to the Deimos base. After the battle, the marine passes through the teleporter and is knocked unconscious by a horde of enemies, awakening with only a pistol. In "The Shores of Hell", the marine fights through corrupted research facilities on Deimos, culminating in the defeat of a gigantic cyberdemon. From an overlook, he discovers that the moon is floating above hell and rappels down to the surface. In "Inferno", the marine battles through hell itself and destroys a cybernetic spider-demon that masterminded the invasion of the moons. When a portal to Earth opens, the marine steps through to discover that Earth has been invaded. "Thy Flesh Consumed" follows the marine's initial assault on the Earth invaders, setting the stage forDoom II.[14]

Development

[edit]Concept

[edit]

Id SoftwarereleasedWolfenstein 3Din May 1992. Later called the "grandfather of 3D shooters",[15][16]it established the genre's popularity and its reputation for fast action and technological advancement.[15][17][18][19]When most of the studio began work on additional episodes forWolfenstein,id co-founder and lead programmerJohn Carmackinstead began technical research on a new game. Following the release ofWolfenstein 3D: Spear of Destinyin September 1992, the team began to plan their next game. They were tired ofWolfensteinand wanted to create another 3D game using a new engine Carmack was developing. Co-founder and lead designerTom Hallproposed a new game in theCommander Keenseries, but the team decided that theKeenplatforming gameplay was a poor fit for Carmack's fast-paced 3D engines. Additionally, the other co-founders, designerJohn Romeroand lead artistAdrian Carmack(no relation to John Carmack) wanted to create something in a darker style than theKeengames.

John Carmack conceived a game about using technology to fight demons, inspired by aDungeons & Dragonscampaignthe team played.This campaign would also influence the design ofQuake(1996) andDaikatana(2000).[20]More broadly the team intended to combine the styles of theEvil Dead IIandAliensfilms.[21][22]The working title wasGreen and Pissed,but Carmack renamed itDoombased on a line from the 1986 filmThe Color of Money:"'What you got in there?' / 'In here? Doom.'"[21][23]

The team agreed to pursue theDoomconcept, and development began in November 1992.[22]The initial development team was composed of five people: programmers John Carmack and Romero, artists Adrian Carmack andKevin Cloud,and designer Hall.[24]They moved operations to a dark office building, naming it "Suite 666" while drawing inspiration from the noises they heard from a neighboring dental practice. They also decided to cut ties withApogee Software,their previous publisher, and self-publishDoom,as they felt that they were outgrowing the publisher and could make more money by self-publishing.[25]

Design

[edit]

In November, Hall delivered adesign documentthat he called the "Doom Bible", detailing the project's plot, backstory, and design goals.[22]His design was a science fiction horror concept wherein scientists on the Moon open a portal to an alien invasion. Over a series of levels, the player discovers that the aliens are demons while hell steadily infects the level design.[6]John Carmack not only disliked the proposed story but dismissed the idea of having a story at all: "Story in a game is like story in a porn movie; it's expected to be there, but it's not that important." Rather than a deep story, he wanted to focus on technological innovation, dropping the levels and episodes ofWolfensteinin favor of a fast, continuous world. Hall disliked the idea, but the rest of the team sided with Carmack.[6]Hall spent the next few weeks reworking theDoom Bibleto work with Carmack's technological ideas.[22]However, the team then realized that Carmack's vision for a seamless world would be impossible given the hardware limitations, and Hall was forced to rework the design document once again.[22]

At the start of 1993, id put out a press release, touting Hall's story about fighting off demons while "knee-deep in the dead". The press release proclaimed the new 3D engine features that John Carmack had created, as well as aspects including multiplayer, that had not yet even been designed.[6]Early versions were built to match theDoom Bible,and a "pre-alpha" version of the first level included Hall's introductory base scene.[26]Initial versions also retainedWolfenstein'sarcade-stylescoring,but this was later removed as it clashed withDoom's intended tone.[24]The studio also experimented with other game systems before removing them, such aslives,an inventory, a secondary shield, and a complex user interface.[22][27]

Soon, however, theDoom Bibleas a whole was rejected. Romero wanted a game even "more brutal and fast" thanWolfenstein,which did not leave room for the character-driven plot Hall had created. Additionally, the team believed it emphasized realism over entertaining gameplay, and they did not see the need for a design document at all.[6]Some ideas were retained, but the story was dropped and most of the design was removed.[28]By early 1993, Hall created levels that became part of an internal demo. Carmack and Romero, however, rejected the military architecture of Hall's level design. Romero especially believed that the boxy, flat level designs failed to innovate onWolfenstein,and failed to show off the engine's capabilities. He began to create his own, more abstract levels, which the rest of the team saw as a great improvement.[6][29]

Hall was upset with the reception of his designs and how little impact he was having as the lead designer.[6][26]He was also upset with how much he was having to fight with John Carmack to get what he saw as obvious gameplay improvements, such as flying enemies, and began to spend less time at work.[22]The other developers, however, felt that Hall was not in sync with the team's vision and was becoming a problem.[30]In July the other founders of id fired Hall, who went to work for Apogee.[6]He was replaced bySandy Petersenin September, ten weeks before the game was released.[31][32]Petersen later recalled that John Carmack and Romero wanted to hire other artists instead, but Cloud and Adrian disagreed, saying that a designer was required to help build a cohesive gameplay experience.[33]The team also added a third programmer,Dave Taylor.[34]

Petersen and Romero designed the rest ofDoom'slevels, with different aims: the team believed that Petersen's designs were more technically interesting and varied, while Romero's were more aesthetically interesting.[32]In late 1993, a month before release, John Carmack began to add multiplayer.[30]After the multiplayer component was coded, the development team began playing four-player games, which Romero termed "deathmatch", and Cloud named the act of killing other players "fragging".[10][30]According to Romero, the deathmatch mode was inspired byfighting gamessuch asStreet Fighter II,Fatal Fury,andArt of Fighting.[35]

Engine

[edit]Doomwas written largely in theCprogramming language, with a few elements inassembly language.The developers usedNeXTcomputers running theNeXTSTEPoperating system.[36]The level and graphical data was stored inWADfiles, short for "Where's All the Data?", separately from the engine. This allowed for any part of the design to be changed without needing to adjust the engine code. Carmack designed this system so that fans could easily modify the game; he had been impressed by themodificationsmade by fans ofWolfenstein 3Dand wanted to support that by releasing a map editor with an easily swappable file structure.[37]

UnlikeWolfenstein,which has flat levels with walls at right angles, theDoomengine allows for walls and floors at any angle or height but does not allow areas to be stacked vertically. The lighting system is based on adjusting the color palette of surfaces directly. Rather than calculating how light traveled from light sources to surfaces usingray tracing,the game calculates the "light level" of a small area based on the predetermined brightness of said area. It then modifies the color palette of that section's surface textures to mimic how dark it would look.[36]This same system is used to cause far away surfaces to look darker than close ones.[6]

Romero came up with new ways to use Carmack's lighting engine, such as strobe lights.[6]He programmed engine features such as switches and movable stairs and platforms.[22][24]After Romero's complex level designs started to cause problems with the engine, Carmack began to usebinary space partitioningto quickly select the reduced portion of a level that the player could see at a given time.[22][32]Taylor, along with programming other features, added cheat codes to aid in development and left them in for players.[24][38]

Art direction

[edit]Adrian Carmack was the lead artist forDoom,with Kevin Cloud as an additional artist. They designed the monsters to be "nightmarish", with graphics that were realistic and dark instead of staged or rendered. Amixed mediaapproach was taken to create them.[39]The artists sculpted models of some of the enemies and took pictures of them instop motionfrom five to eight different angles so that they could be rotated realistically in-game. The images were then digitized and converted to 2D characters with a program written by John Carmack.[6]Adrian Carmack made clay models for a few demons and hadGregor Punchatzbuild latex and metal sculptures of the others.[22][24]The weapons were made from combined parts of children's toys.[22]The developers photographed themselves as well, using Cloud's arm for the marine's arm holding a gun, and Adrian's snakeskin boots and wounded knee for textures.[6]The cover art was created byDon Ivan Punchatz,Gregor Punchatz's father, who worked from a short description of the game rather than detailed references. Romero was the body model used for cover; he posed during a photoshoot to demonstrate to the intended model what the pose should look like, and Punchatz used his photo.[30]

As withWolfenstein 3D,id hired composerBobby Princeto create the music and sound effects. Romero directed Prince to make the music intechnoandmetalstyles. Many tracks were directly inspired by songs by metal bands such asAlice in ChainsandPantera.[32][40]Prince believed thatambient musicwould be more appropriate and produced numerous tracks in both styles in hope of convincing the team, and Romero incorporated both.[41]Prince did not make music for specific levels, as they were composed before the levels were completed. Instead, Romero assigned each track to each level late in development. Prince created the sound effects based on short descriptions or concept art of a monster or weapon and adjusted them to match the completed animations.[42]The monster sounds were created from animal noises, and Prince designed all the sounds to be distinct on the limited sound hardware of the time, even when many sounds were playing at once.[32][41]He also designed the sound effects to play on different frequencies from those used for theMIDImusic, so they would clearly cut through the music.[43]

Release

[edit]Id Software planned to self-publishDoomforDOS-based computers and set up a distribution system leading up to the release. Jay Wilbur, who had been hired as CEO and sole member of the business team, planned the marketing and distribution ofDoom.As id would make the most money from copies they sold directly to customers—up to 85% of the plannedUS$40price—he decided to leverage thesharewaremarket as much as possible. He believed that the mainstream press was uninterested in the game and bought only a single ad in any gaming magazine. Instead, he gave software retailers the option to sell copies of the firstDoomepisode at any price, in hopes of motivating customers to buy the full game directly from id.[32]

The team planned to releaseDoomin the third quarter of 1993 but ultimately needed more time. By December 1993, the team was working non-stop, with several employees sleeping at the office. Taylor said that the work gave him such a rush that he would pass out from the intensity.[10]Id only gave a single press preview, toComputer Gaming Worldin June, to a glowing response, but had also released development updates to the public continuously throughout development on the nascentinternet.Id began receiving calls from people interested in the game or angry that it had missed its planned release date, as anticipation built over the year. At midnight on December 10, 1993, after working for 30 straight hours testing, the development team at id uploaded the first episode to the internet, letting interested players distribute it for them.[30]The team was unable to connect to theFTPserver at theUniversity of Wisconsin–Madisonwhere they planned to upload the game, since there were so many users already connected in anticipation of the release. The network administrator was forced to first increase the number of connections, and then kick off all users to make room. When the upload finished 30 minutes later, 10,000 people attempted to download the game at once, crashing the university's network.[10]

Within hours ofDoom's release, university networks began banningDoommultiplayer games, as a rush of players overwhelmed their systems.[10]The morning after release, John Carmack quickly released a patch in response to complaints of network congestion from administrators, who still needed to implementDoom-specific rules to keep their networks from crashing from the load.[44]

Ports

[edit]

In 1995, id created an expanded version ofDoomfor the retail market with a fourth episode of levels, which was published byGT InteractiveasThe Ultimate Doom.[46]Doomhas also been ported to numerous different platforms, independent from id Software. The first port ofDoomwas an unofficial port to Linux, released by id programmer Dave Taylor in 1994; it was hosted by id but not supported or made official.[47]Microsoft attempted to hire id to portDoomto Windows in 1995 to promote Windows as a gaming platform, and Microsoft CEOBill Gatesbriefly considered buying the company.[48][49]When id declined, Microsoft made its own licensed port, with a team led byGabe Newell.[50]One promotional video for Windows 95 had Gates digitally superimposed into the game.[45]

Other official ports ofDoomwere released for the32XandAtari Jaguarin 1994,SNESandPlayStationin 1995,3DOin 1996,Sega Saturnin 1997,AcornRisc PCin 1998,Game Boy Advancein 2001,Xbox 360in 2006,iOSin 2009, andNintendo Switch,Xbox One,PlayStation 4,andAndroidin 2019, with the latter-most platforms (excluding Android) receiving a further expanded port alongsideDoom IIin 2024 along with ports for thePlayStation 5andXbox Series X/S.[51][52][53][54][55][56]Some of these became bestsellers even many years after the initial release.[57]The ports did not all have the same content, with some having fewer levels, such as the 32X port created by John Carmack, which was released with only two-thirds of the game's levels in order to meet the console's launch date, while the PlayStation port includesThe Ultimate DoomandDoom II.[58][59]The source code forDoomwas released under a non-commercial license in 1997, and freely released under theGNU General Public Licensein 1999.[60][61]Due to the release of its source code,Doomhas been unofficially ported to numerous platforms. These ports include esoteric devices such as smart thermostats, pianos, andDoomitself, which led to variations of a long-runningmeme,"Can it runDoom?"and" It runsDoom".[62][63][64]

Reception

[edit]Sales

[edit]Upon its release in December 1993,Doombecame an "overnight phenomenon".[65]It was an immediate financial success for id, making a profit within a day after release. Although the company estimated that only 1% of shareware downloaders bought the full game, this was enough to generate initial daily revenue ofUS$100,000,selling in one day whatWolfensteinhad sold in one month.[65][66]By May 1994, Wilbur said that the game had sold over 65,000 copies, and estimated that the shareware version had been distributed over 1 million times.[67]In 1995, Wilbur estimated the first-year sales as 140,000, while in 2002 Petersen said it had sold around 200,000 copies in its first year.[68][69]

By late 1995,Doomwas estimated to be installed on more computers worldwide than Microsoft's new operating system,Windows 95.[50]According toPC Data,by April 1998Doom's shareware edition had yielded 1.36 million units sold andUS$8.74 millionin revenue in the United States. This led PC Data to declare it the country's 4th-best-selling computer game since 1993.[70]The Ultimate Doomsold over 780,000 units by September 1999, and all versions combined sold 3.5 million copies by the end of 1999.[71][72]In addition to sales, an estimated six million people played the shareware version by 2002; other sources estimated in 2000 that 10–20 million people playedDoomwithin 24 months of its launch.[69][73]

Reviews

[edit]Doomwas highly praised in contemporaneous reviews. In April 1994, a few months after release,PC Gamer UKnamed it the third-best computer game of all time, claiming "Doomhas already done more to establish the PC's arcade clout than any other title in gaming history, "andPC Gamer USnamed it the best computer game of all time that August.[74][75]It won the Best Action Adventure award atCybermania '94.[76]GamesRadar UKnamedDoomGame of the Year in 1993 shortly after release, andComputer Gaming WorldandPC Gamer UKdid the same the year after.[76][77][78]

Reviewers heavily praised the single-player gameplay:Electronic Entertainmentcalled it "a skull-banging, palm-sweating, blood-pounding game", whileThe Agesaid it was "a technically superb and thrilling 3D adventure".[79][80]PC Zonecalled it the best arcade game ever, and it andComputer Gaming Worldpraised the variety of monsters and weapons.[81][82]Computer Gaming Worldconcluded that it was "a virtuoso performance".[82]Other reviewers, while also praising the gameplay, commented on the lack of complexity:Computer and Video Gamesfound it captivating and praised the variety and complexity of the level design, but called the overall gameplay repetitive, whileDragonsimilarly praised the fast gameplay and level design, but said that overall it lacked depth.[83][84]Edgepraised the graphics and levels but criticized the straightforward shooting gameplay. The review concluded: "If only you could talk to these creatures, then perhaps you could try and make friends with them, form alliances... Now, that would be interesting."[85]The review attracted mockery and "if only you could talk to these creatures" became a running joke invideo game culture.[86]The multiplayer gameplay was praised:Computer Gaming Worldcalled it "the most intense gaming experience available", andDragoncalled it "the biggest adrenaline rush available on computers".[82][84]PC Zonenamed it as the best multiplayer game available, in addition to the best arcade game.[81]

The 3D graphics and art style were praised by reviewers;Computer Gaming Worldcalled the graphics remarkable, whileEdgesaid that it "made serious advances in what people will expect of 3D graphics in future", surpassing not only prior games but games that had yet to be released.[82][85]Compute!andElectronic Gamessimilarly called the graphics excellent and unlike any other game's.[87][88]PC Zone,Dragon,Computer Gaming World,andElectronic Entertainmentall praised the atmosphere and art direction, saying that the level design, lighting effects, and sound effects combined to create a "claustrophobic" and "nightmarish experience".[79][81][82][84]Computer Gaming Worldalso praised the music, as didThe Mercury News,which called it as "ominous as the scenario".[80][82]

Other versions

[edit]The Ultimate Doomreceived mixed reviews upon its release in 1995, as in the review fromPC Zone,which gave it a score of 90/100 for new players but 20/100 for anyone who had the original game. The reviewer viewed it as solely a level pack due to the lack of new features and compared it negatively to the hundreds of free fan-made levels available on the internet.[89]Joystickdisliked the limited amount of additional content and recommended it only to major fans or those who had not played it.[90]Fusionreviewed the edition positively, praising the difficulty of the new levels, as didGameSpot,which reviewed it from the perspective of introducing the game to new players.[91][92]

The first ports ofDoomreceived comparable reviews to the original PC version.VideoGames,GamePro,andComputer and Video Gamesall gave the Jaguar version high scores, comparing it favorably with the PC version.[93][94][95]GameProandComputer and Video Gamesalso rated the 32X version highly, though they noted that the graphics were worse and the game shorter than the PC or Jaguar versions.[95][96]The 1995 ports received mixed reviews. The PlayStation version was rated highly byHobbyConsolas,GamePro,andMaximum,which praised the inclusion ofDoom IIand extra levels, and favorably compared it to other PlayStation shooter games.[59][97][98]The SNES version, however, was noted for weaker graphics and unresponsive controls, though reviewers such asComputer and Video Games,GamePro,andNext Generationwere split on awarding high or middling scores due to these faults.[99][100][101]Later 1990s ports received worse reviews; the 3DO port was panned byGameProandMaximumfor having worse graphics, a smaller screen size, and less intelligent enemies than any previous version,[102][103]and the Sega Saturn port also met with low reviews for poor graphics and low quality fromMean MachinesandSega Saturn Magazine.[104][105]

Legacy

[edit]Doomhas been termed "inarguably the most important" first-person shooter, as well as the "father" of the genre.[106][107]Although not the first in the genre, it was the game with the greatest impact.[106][107][108]Dan Pinchbeck inDoom: Scarydarkfast(2013) noted the direct influence ofDoom's design choices on those of first-person and third-person shooter games two decades later, as influenced by the games released in the intervening years.[109]

Doom,and to a lesser extentWolfenstein 3D,has been characterized as "mark[ing] a turning point" in the perception of video games in popular culture, withDoomand first-person shooters in general becoming the predominant perception of video games in media.[110]Historians such as Tristan Donovan inReplay: The History of Video Games(2010) have termed it as causing a "paradigm shift", prompting the rise in popularity of 3D games, first-person shooters, licensed technology between developers, and support for game modifications.[111]It helped spark the rise of both online multiplayer games and player-driven content generation, and popularized the business model of online distribution.[112][113]In their bookDungeons & Dreamers: A Story of how Computer Games Created a Global Communityin 2014, Brad King and John Borland claimed thatDoomwas one of the first widespread instances of an "online collective virtual reality",[114]and did more than any other game to create a modern world of "networked games and gamers".[115]PC GamerproclaimedDoomthe most influential game of all time in 2004, and in 2023 said its development was one of the most well-documented in the history of video games.[116][117]

It has also been used in scholarly research since its release, including formachine learning,[118][119]video game aesthetics and design,[120]and the effects of video games on aggression, memory, and attention.[121][122]In 2007Doomwas listed among the ten "game canon"video games selected for preservation by theLibrary of Congress,[123][124][125]and in 2015The Strong National Museum of PlayinductedDoomto itsWorld Video Game Hall of Fameas part of its initial set of games.[126]

Doomhas continued to be included highly inlists of the best video games everfor nearly three decades since its release. In 1995,Next Generationsaid it was "the most talked about PC game ever".[127]The PC version was ranked the 3rd best video game byFluxin 1995, and in 1996 was ranked fifth best and third most innovative byComputer Gaming World.[128][129][130]In 2000,Doomwas ranked as the second-best game ever byGameSpot.[131]The following year, it was voted the number one game of all time in a poll among over 100 game developers and journalists conducted byGameSpy,and was ranked the sixth best game byGame Informer.[132][133]GameTrailersranked it the most "breakthrough PC game" in 2009 andGame Informeragain ranked it the sixth-best game that same year.[134][135]Doomhas also been ranked among the best games of all time byGamesMaster,[136]Hyper,[137]The Independent,[138]Entertainment Weekly,[139]GamesTM,[140]Jeuxvideo.com,[141]Gamereactor,[142]Time,[143]Polygon,[144]andThe Times,among others, as recently as 2023.[145]

Clones

[edit]

The success ofDoomled to dozens of new first-person shooter games.[146]In 1998,PC Gamerdeclared it "probably the most imitated game of all time".[147]These games were often referred to as "Doomclones",with" first-person shooter "only overtaking it as the name of the genre after a few years.[148][149][150]As the "first-person shooter" genre label had not yet solidified at the time,Doomwas described as a "first person perspective adventure" and "atmospheric 3-D action game".[110]

Doomclones ranged from close imitators to more innovative takes on the genre. Id Software licensed theDoomengineto several other companies, which resulted in several games similar toDoom,includingHeretic(1994),Hexen: Beyond Heretic(1995), andStrife: Quest for the Sigil(1996).[149]ADoom-based game calledChex Questwas released in 1996 byRalston Foodsas a promotion to increase cereal sales.[151]Other games were inspired byDoom,if not rumored to be built byreverse engineeringthe game's engine, includingLucasArts'sStar Wars: Dark Forces(1995).[149][152]Several other games termedDoomclones, such asPowerSlave(1996) andDuke Nukem 3D(1996), used the 1995Build engine,a 2.5D engine inspired byDoomcreated byKen Silvermanwith some consultation with John Carmack.[149][153]

Sequel and franchise

[edit]After completingDoom,id Software began working on a sequel using the same engine,Doom II,which was released to retail on October 10, 1994, ten months after the first game. GT Interactive had approached id before the release ofDoomwith plans to release a retail version ofDoomandDoom II.Id chose to create the sequel as a set of episodes rather than a new game, allowing John Carmack and the other programmers to begin work on id's next game,Quake.[154]Doom IIwas the United States' highest-selling software product of 1994 and sold more than1.2 millioncopies within a year.[155][156]

Doom IIwas followed by an expansion pack from id,Master Levels for Doom II(1995), consisting of 21 commissioned levels and over 3000 user-created levels forDoomandDoom II.[157]Two sets ofDoom IIlevels by different amateur map-making teams were released together by id as the standalone gameFinal Doom(1996).[158][159]DoomandDoom IIwere both included, along with previous id games, in theid Anthologycompilation (1996).[160]TheDoomfranchisehas continued since the 1990s in several iterations and forms. The video game series includesDoom 3(2004),Doom(2016), andDoom Eternal(2020), along with other spin-off video games.[161][162][163][164]It additionally includesmultiple novels,a comic book, board games, and two films:Doom(2005) andDoom: Annihilation(2019).[165][166][167]

Controversies

[edit]

Doomwas notorious for its high levels ofgraphic violenceandsatanicimagery, which generated controversy from a broad range of groups.[168]Doomfor the 32X was one of the first video games to be given a Mature 17+ rating from theEntertainment Software Rating Boarddue to its violent gore and nature, whileDoom IIwas the first.[168][169][170]In Germany, shortly after its publication,Doomwas classified as "harmful to minors" by theFederal Department for Media Harmful to Young Personsand could not be sold to children or displayed where they could see it, which was only rescinded in 2011.[171]

Doomagain sparked controversy in the United States when it was found thatEric Harris and Dylan Klebold,who committed theColumbine High School massacreon April 20, 1999, were avid players.[172]While planning for the massacre, Harris said in his journal that the killing would be "like playingDoom".[173]A rumor spread afterward that Harris had designed a customDoomlevel that looked like the high school, populated with representations of Harris's classmates and teachers, which he used to practice for the shooting.[174]Although Harris did design several customDoomlevels, which later became known as the "Harris levels",none were based on the school.[174]Doomwas dubbed a "mass murder simulator" by critic and Killology Research Group founderDavid Grossman.[175]

In the earliest release versions, the level E1M4: Command Control contains aswastika-shaped structure, which was put in as a homage toWolfenstein 3D.The swastika was removed in later versions, out of respect for a military veteran's request, according to Romero.[24]

Community

[edit]Doom's popularity and innovations attracted a community that has persisted for decades since.[176]The deathmatch mode was an important factor in its popularity.[11]Doomwas the first game to coin the term "deathmatch" and introduced multiplayer shooting battles to a wide audience.[176][177]This led to a widespread community of players who had never experienced fast-paced multiplayer combat before.[176]

Another popular aspect ofDoomwas the versatility of its WAD files, enablinguser-generated levelsand other game modifications. John Carmack and Romero had strongly advocated for mod support, overriding other id employees who were concerned about commercial and legal implications. Although WAD files exposed the game data, id provided no instructions for how they worked. Still, players were able to modify leaked alpha versions of the game, allowing them to release level editors within weeks of the game's release.[178]

On January 26, 1994, university student Brendon Wyber led a group to create the first fulllevel editor,the Doom Editor Utility, leading to the first custom level by Jeff Bird in March.[178][179]It was followed by "countless" others, including many based on other franchises likeAliensandStar Warstotal conversion mods,as well as DeHackEd, a patch editor first released in 1994 by Greg Lewis that allowed editing of the game engine.[178][180]Soon after the first mods appeared, id CEO Wilbur posted legal terms to the company's website, allowing mod authors to charge money without any fees to id, while also absolving the company of responsibility or support.[178]

Doommods were widely popular, earning favorable comparisons to the official level additions seen inThe Ultimate Doom.[89][90]Thousands of user-created levels were released in the first few years after the release; over 3000 such levels forDoomandDoom IIwere included in the official retail releaseMaster Levels for Doom II(1995).[157]WizardWorksreleased multiple collections of mods ofDoomandDoom IIunder the nameD!Zone.[181]At least one mod creator,Tim Willits,was later hired at id Software.[182]Mods have continued to be produced, with the community Cacowards awarding the best of each year.[183]In 2016, Romero created two newDoomlevels: E1M4b ( "Phobos Mission Control" ) and E1M8b ( "Tech Gone Bad" ).[184][185]In 2018, for the 25th anniversary ofDoom,Romero announcedSigil,an unofficial fifth episode containing nine levels. It was released on May 22, 2019, for€6.66with a soundtrack byBuckethead,and then released again for free on May 31 with a soundtrack by James Paddock. A physical release was later produced.[186][187]A sixth episode,Sigil II,was released on the game's 30th anniversary, December 10, 2023, again for€6.66for a digital copy with a soundtrack byValient Thorr,as well as physical editions onfloppy disk.[188]

In addition to WAD files,Doomincludes a feature that allowed players to record and play back gameplay using files calleddemos,or game replays.[189]Although the concept ofspeedrunninga video game existed beforeDoom,its release coincided with a wave of popularity for speedrunning, amplified by theonline communitiesbuilt on the nascent Internet.[190]Demos were lightweight files that could be shared more easily than video files on internetbulletin board systemsat the time.[189]As a result,Doomis credited with creating the video game speedrunning community.[191][192]The speedrunning community forDoomhas continued for decades. As recently as 2019, community members have broken records originally set in 1998.[193]Doomhas been termed as having "one of the longest-running speedrunning communities" as well as being "the quintessential speedrunning game".[194][195]

Notes

[edit]- ^The music for the PlayStation and Sega Saturn ports of the game was composed byAubrey Hodges,[1]while the 2024 release featured the 2016 "IDKFA" arrangement soundtrack byAndrew Hulshult.

- ^The 2019 release usesUnity,while the 2024 release uses theKEX Engine.

References

[edit]- ^Niver, John (August 1, 2012)."Doom Music".Video Game Music Online.Archivedfrom the original on August 3, 2020.RetrievedAugust 20,2023.

- ^"The First Pictures: Quake: The Fight for Justice".Maximum.No. 1.EMAP.October 1995. pp. 134–135.ISSN1360-3167.

Doom was criticised for not being a true 3D product – in fact, it's best described as 2.5D (if you will) because although each level could be staged at various heights, it was impossible to stack two corridors on top of one another in any given stage.

- ^Swaim, Michael; Macy, Seth G. (January 17, 2020)."Doom Eternal: The Story So Far".IGN.Ziff Davis.Archivedfrom the original on November 12, 2022.RetrievedNovember 12,2022.

- ^abWalters, Michael (July 28, 2019)."Doom (1993) Nintendo Switch Review: A Classic That Refuses To Feel Dated".The Gamer.Valnet.Archivedfrom the original on November 12, 2022.RetrievedNovember 12,2022.

- ^Thompson, Tommy (May 2, 2022)."The AI of Doom (1993)".Game Developer.Informa.Archivedfrom the original on November 12, 2022.RetrievedNovember 12,2022.

- ^abcdefghijklKushner,pp. 124–131

- ^"The 10 Greatest Cheat Codes in Gaming HistoryDoom: God Mode".Complex Networks.Archivedfrom the original on July 17, 2017.RetrievedJuly 12,2017.

- ^Anthony, Sebastian (December 10, 2013)."Doom, the original and best first-person shooter, is 20 years old today".ExtremeTech.Ziff Davis.Archivedfrom the original on October 22, 2017.RetrievedJuly 12,2017.

- ^Keizer, Gregg (April 1994)."Virtual Worlds - Doom".Electronic Entertainment.No. 4.IDG.p. 94.ISSN1074-1356.

- ^abcdefKushner,pp. 148–153

- ^abKushner,pp. 182–184

- ^Pinchbeck,pp. 65–66

- ^Doom Manual.id Software.1993.Archivedfrom the original on April 14, 2022.RetrievedDecember 4,2020.

- ^Good, Owen S. (June 1, 2019)."Original Doom gets unofficial sequel from creator, for free".Polygon.Vox Media.Archivedfrom the original on December 16, 2022.RetrievedAugust 31,2023.

- ^ab"Computer Gaming World's Hall of Fame".1Up.com.Ziff Davis.Archived fromthe originalon July 27, 2016.RetrievedJuly 27,2016.

- ^Slaven,p. 53

- ^Williamson, Colin."Wolfenstein 3D DOS Review".AllGame.All Media Network.Archived fromthe originalon November 15, 2014.RetrievedJuly 27,2016.

- ^"IGN's Top 100 Games (2003)".IGN.Ziff Davis.Archived fromthe originalon April 19, 2016.RetrievedJuly 27,2016.

- ^Shachtman, Noah (May 5, 2008)."May 5, 1992: Wolfenstein 3-D Shoots the First-Person Shooter Into Stardom".Wired.Condé Nast.Archived fromthe originalon October 25, 2011.RetrievedJuly 27,2016.

- ^Romero,pp. 126–145

- ^abKushner,pp. 118–121

- ^abcdefghijkRomero, John;Hall, Tom(2011).Classic Game Postmortem – Doom(Video).Game Developers Conference.Archivedfrom the original on August 6, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 6,2018.

- ^Antoniades, Alexander (August 22, 2013)."Monsters from the Id: The Making of Doom".Gamasutra.UBM.Archivedfrom the original on September 25, 2018.RetrievedMarch 3,2018.

- ^abcdef"We Play Doom with John Romero".IGN.Ziff Davis.December 10, 2013.Archivedfrom the original on January 11, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 2,2018.

- ^Kushner,pp. 122–123

- ^abBatchelor, James (January 26, 2015)."Video: John Romero reveals level design secrets while playing Doom".MCV.NewBay Media.Archivedfrom the original on February 2, 2018.RetrievedFebruary 2,2018.

- ^"On the Horizon".Game Players PC Entertainment.Vol. 6, no. 3. GP Publications. May 1993. p. 8.ISSN1087-2779.

- ^Mendoza,pp. 249–250

- ^Romero, John;Barton, Matt (March 13, 2010).Matt Chat 53: Doom with John Romero(Video). Matt Barton. Event occurs at 4:15–8:00.Archivedfrom the original on November 24, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 2,2018.

- ^abcdeRomero,ch. 12: Destined to DOOM

- ^Bub, Andrew S. (July 10, 2002)."Sandy Petersen Speaks".GameSpy.Ziff Davis.Archived fromthe originalon March 22, 2005.RetrievedJanuary 31,2018.

- ^abcdefKushner,pp. 132–147

- ^Petersen, Sandy(April 20, 2020).Tales from the Dark Days of Id Software(Video). Event occurs at 0:45–1:30.Archivedfrom the original on March 15, 2022.RetrievedMarch 15,2022– viaYouTube.

- ^Romero, John(2016).The Early Days of id Software(Video).Game Developers Conference.Archivedfrom the original on July 7, 2017.RetrievedFebruary 5,2018.

- ^Consalvo,pp. 201–203

- ^abSchuytema, Paul C. (August 1994). "The Lighter Side of Doom".Computer Gaming World.No. 121. pp. 140–142.ISSN0744-6667.

- ^Kushner,p. 166

- ^Stuart, Keith (December 8, 2023)."Doom at 30: what it means, by the people who made it".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on December 17, 2023.RetrievedDecember 18,2023.

- ^Mendoza,p. 247

- ^Romero, John(April 19, 2005)."Influences on Doom Music".rome.ro. Archived fromthe originalon September 1, 2013.RetrievedFebruary 6,2018.

- ^abPinchbeck,pp. 52–55

- ^Prince, Bobby(December 29, 2010)."Deciding Where To Place Music/Sound Effects In A Game".Bobby Prince Music.Archivedfrom the original on August 12, 2011.RetrievedFebruary 6,2018.

- ^Tobin, Scott;Prince, Bobby(October 12, 2018).Composers Play – "Doom" Coop with Bobby Prince! – Part 4(Video). Event occurs at 5:00–5:30.Archivedfrom the original on May 12, 2023.RetrievedJune 22,2023– viaYouTube.

- ^Totilo, Steven (December 10, 2013)."Memories Of Doom, By John Romero & John Carmack".Kotaku.G/O Media.Archivedfrom the original on October 15, 2018.RetrievedOctober 14,2018.

- ^abKlepek, Patrick (May 16, 2016)."That Time Bill Gates Starred In A Doom Promo Video".Kotaku.G/O Media.Archivedfrom the original on February 2, 2023.RetrievedJune 22,2023.

- ^"The Ultimate Doom: Thy Flesh Consumed".Jeuxvideo.com(in French).Archivedfrom the original on November 4, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 22,2018.

- ^Taylor, Dave(September 9, 1994)."Linux Doom for X released".Newsgroup:comp.os.linux.announce.Usenet:[email protected].Archivedfrom the original on March 28, 2017.

- ^Wilson, Johnny L.; Brown, Ken; Lombardi, Chris; Weksler, Mike; Coleman, Terry (July 1994). "The Designer's Dilemma: The Eighth Computer Game Developers Conference".Computer Gaming World.pp. 26–31.ISSN0744-6667.

- ^Kushner,pp. 217–219

- ^abSebastian, Anthony (September 24, 2013)."Gabe Newell Made Windows a Viable Gaming Platform, and Linux Is Next".ExtremeTech.Ziff Davis.Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2016.RetrievedAugust 11,2015.

- ^"Doom (1993) – PC".IGN.Ziff Davis.Archivedfrom the original on April 30, 2017.RetrievedDecember 19,2017.

- ^Hawken,ch. Doom

- ^Cobbett, Richard (August 3, 2012)."Doom 3 shines flashlight on The Lost Mission (And doesn't even need to put down its gun!)".PC Gamer.Future.Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2015.RetrievedJanuary 22,2018.

- ^Gach, Ethan (July 26, 2019)."Looks Like The Original Doom Games Are Coming To Switch As Soon As Today [Update]".Kotaku.G/O Media.Archivedfrom the original on May 4, 2023.RetrievedJune 22,2023.

- ^Lyles, Taylor (August 8, 2024)."DOOM and DOOM 2 Getting New Enhanced Versions With a Brand-New Episode and More".IGN.RetrievedAugust 8,2024.

- ^Peters, Jay (August 8, 2024)."Doom and Doom II get a 'definitive' re-release that's packed with upgrades".The Verge.RetrievedAugust 8,2024.

- ^"Gallup UK PlayStation sales chart".Official UK PlayStation Magazine.No. 5.Future.April 1996.ISSN1752-2102.

- ^McFerran, Damien (May 2010). "Retroinspection: Sega 32X".Retro Gamer.No. 77.Imagine Publishing.pp. 44–49.ISSN1742-3155.

- ^ab"Doom".Maximum.No. 2.EMAP.November 1995. pp. 148–149.ISSN1360-3167.

- ^"Doom Open Source Release".GitHub.Microsoft.Archivedfrom the original on June 15, 2023.RetrievedJune 19,2023.

- ^DeCarlo, Matthew (March 11, 2010)."A List of PC Game Classics Available Free of Charge".TechSpot.Archivedfrom the original on May 26, 2022.RetrievedJune 20,2023.

- ^"But Can It Run Doom?".Wired.Condé Nast.January 1, 2003.Archivedfrom the original on April 29, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 22,2018.

- ^Hurley, Leon (May 15, 2017)."Watch Doom running on an ATM, a printer... and 10 other weird, non-gaming machines".GamesRadar+.Future.Archivedfrom the original on July 18, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 22,2018.

- ^Petitte, Omri (February 2, 2016)."Pianos, printers, and other surprising things you can play Doom on".PC Gamer.Future.Archivedfrom the original on October 6, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 22,2018.

- ^abKushner,pp. 176–178

- ^Kushner,pp. 113–117

- ^"Lovers of guts and gore should meet this Doom".The Courier-Journal.May 7, 1994. p. 20.RetrievedOctober 5,2023– viaNewspapers.com.

- ^"Games".Fort Worth Star-Telegram.October 29, 1995. p. 93.Archivedfrom the original on May 22, 2022.RetrievedJanuary 7,2022– viaNewspapers.com.

- ^abMcCandless, David (June 12, 2002)."Games That Changed The World:Doom".PC Zone.Future.Archived fromthe originalon July 9, 2007.RetrievedJuly 24,2018.

- ^"Player Stats: Top 10 Best-Selling Games, 1993 – Present".Computer Gaming World.No. 170. September 1998. p. 52.ISSN0744-6667.

- ^"PC Data Top Games of All Time".IGN.Ziff Davis.November 1, 1999. Archived fromthe originalon March 2, 2000.RetrievedMay 31,2018.

- ^Clark, Stuart (February 20, 1999)."Denting the ego of Id".The Sydney Morning Herald.p. 209.Archivedfrom the original on August 21, 2023.RetrievedSeptember 7,2021– viaNewspapers.com.

- ^Dunnigan,pp. 14–17

- ^"The PC Gamer Top 50 PC Games of All Time".PC Gamer UK.Vol. 1, no. 5.Future.April 1994. pp. 43–56.ISSN1351-3540.

- ^"Top 40: The Best Games of All Time".PC Gamer US.Vol. 1, no. 3.Future.August 1994. p. 42.ISSN1080-4471.

- ^ab"Brenda Romero and John Romero Bios".Romero.com.Archivedfrom the original on March 15, 2023.RetrievedAugust 21,2023.

- ^"The PC Gamer Games of the Year".PC Gamer UK.Vol. 2, no. 1.Future.December 1994.ISSN1351-3540.

- ^"Announcing The New Premier Awards".Computer Gaming World.No. 118. June 1994. pp. 51–58.ISSN0744-6667.

- ^abKeizer, Gregg (April 1994)."Doom".Electronic Entertainment.No. 4.International Data Group.p. 94.ISSN1074-1356.

- ^abCox, Kate (October 17, 2012)."Six Reviewers Travel From The Past To Shoot Their Way Through Doom".Kotaku.G/O Media.Archivedfrom the original on June 13, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^abcMcCandless, David (April 1994). "Review: Doom".PC Zone.No. 13.Future.pp. 68–72.ISSN0967-8220.

- ^abcdefWalker, Bryan (March 1994). "Hell's Bells and Whistles: id Software's Doom".Computer Gaming World.No. 116. pp. 38–39.ISSN0744-6667.

- ^Rand, Paul; Lord, Gary (March 1994). "Reviews: Doom".Computer and Video Games.No. 148.Future.pp. 72–73.ISSN0261-3697.

- ^abcKaufman, Doug (March 1994). "Eye of the Monitor: Doom".Dragon.No. 203.TSR.pp. 59–62.ISSN1062-2101.

- ^ab"Doom Review".Edge.No. 7.Future.April 1994.ISSN1350-1593.Archived fromthe originalon October 23, 2012.

- ^Welsh, Oli (March 17, 2012)."Game of the Week: Journey".Eurogamer.Gamer Network.Archivedfrom the original on May 29, 2023.RetrievedOctober 3,2023.

- ^Atkin, Denny (April 1994)."Sim Hillary".Compute!.Vol. 16, no. 4.ABC Publishing.p. 82.ISSN0194-357X.

- ^Ceccola, Russ (April 1994)."Doom: Save Phobos From the Demons of Hell".Electronic Games.Vol. 2, no. 7. Katz Kunkel Worley. p. 74.ISSN0730-6687.

- ^abMcCandless, David (August 1995)."Ultimate Doom: Thy Flesh Consumed".PC Zone.No. 29.Future.pp. 62–64.ISSN0967-8220.

- ^ab"The Ultimate Doom".Joystick(in French). No. 68.Hachette Filipacchi Médias.p. 89.ISSN1145-4806.

- ^Hummer, Sadie (September 1995). "See You In Hell, My Friend".Fusion.Vol. 1, no. 2. Decker Publications. p. 80.ISSN1083-1118.

- ^Scisco, Peter (May 1, 1996)."The Ultimate Doom Review".GameSpot.SpotMedia Communications. Archived fromthe originalon September 7, 2011.RetrievedApril 9,2020.

- ^Loftus, Jim (January 1995)."Doom".VideoGames.No. 72.Larry Flynt Publications.p. 76.ISSN1059-2938.

- ^Peteroo (January 1995). "Doom—Jaguar".GamePro.No. 66.International Data Group.pp. 92–93.ISSN1042-8658.

- ^ab"Doom versus Doom".Computer and Video Games.No. 158.Future.January 1995. pp. 72–74.ISSN0261-3697.

- ^Toxic Tommy (February 1995). "Doom—32X".GamePro.No. 67.International Data Group.p. 58.ISSN1042-8658.

- ^Lorente, Roberto (June 1996). "Doom".HobbyConsolas(in Spanish). No. 57.Axel Springer SE.pp. 94–95.ISSN1134-6582.

- ^Major Mike (December 1995). "Doom: Special PlayStation Edition".GamePro.No. 77.International Data Group.pp. 58–59.ISSN1042-8658.

- ^Lord, Gary; Patterson, Mark (October 1995). "Doom".Computer and Video Games.No. 167.Future.pp. 82–83.ISSN0261-3697.

- ^The Axe Grinder (October 1995). "Doom–Super NES".GamePro.No. 68.International Data Group.p. 66.ISSN1042-8658.

- ^"Doom".Next Generation.Vol. 1, no. 10.Imagine Media.October 1995. pp. 126, 128.ISSN1078-9693.

- ^"Quick Hits: Doom—3DO".GamePro.No. 92.International Data Group.May 1996. p. 72.ISSN1042-8658.

- ^"Doom for the 3DO?".Maximum.No. 4.EMAP.February 1996. pp. 160–161.ISSN1360-3167.

- ^"Doom".Mean Machines.No. 53.EMAP.March 1997. pp. 66–68.ISSN0960-4952.

- ^Leadbetter, Rich (February 1997). "Doom".Sega Saturn Magazine.No. 16.EMAP.pp. 72–73.ISSN1360-9424.

- ^abShoemaker, Brad (2012)."The Greatest Games of All Time: Doom".GameSpot.CBS Interactive.Archived fromthe originalon October 11, 2012.RetrievedJune 13,2023.

- ^abDastoor, Vaspaan (May 9, 2019)."Most Impactful FPS Games of All Time".IGN.Ziff Davis.Archivedfrom the original on June 14, 2023.RetrievedJune 13,2023.

- ^Moss, Richard (February 14, 2016)."Headshot: A visual history of first-person shooters".Ars Technica.Archivedfrom the original on October 15, 2017.RetrievedOctober 14,2017.

- ^Pinchbeck,pp. 157–159

- ^abTherrien, Carl (2015)."Inspecting Video Game Historiography Through Critical Lens: Etymology of the First-Person Shooter Genre".Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research.15(2).Archivedfrom the original on June 1, 2023.RetrievedAugust 20,2023.

- ^Donovan,pp. 261–262

- ^Pinchbeck,p. 165

- ^Zachary, George (September 1996). "Generator: How a Little Game Called Doom May Have Changes the Business World Forever".Next Generation.No. 21.Imagine Media.p. 20.ISSN1078-9693.

- ^King; Borland,ch. 15: "The Doom Connection"

- ^King; Borland,ch. 12: "id and Ego"

- ^"Ten Years of PC Gamer Magazine".PC Gamer US.No. 123.Future.May 2004.ISSN1080-4471.

- ^Lane, Rick (January 31, 2024)."Doom is eternal: The immeasurable impact of gaming's greatest FPS".PC Gamer.Future.RetrievedFebruary 7,2024.

- ^Kanervisto, A.; Pussinen, J.; Hautamäki, V. (2020).Benchmarking End-to-End Behavioural Cloning on Video Games.2020 IEEE Conference on Games,Osaka, Japan. pp. 558–565.arXiv:2004.00981.doi:10.1109/CoG47356.2020.9231600.

- ^Alvernaz, S.; Togelius, J. (2017).Autoencoder-augmented neuroevolution for visual doom playing.2017 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Games, New York, NY, USA. pp. 1–8.arXiv:1707.03902.doi:10.1109/CIG.2017.8080408.

- ^Hutchison, Andrew (2008)."Making the water move: techno-historic limits in the game aesthetics of Myst and Doom".Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research.8(1).Archivedfrom the original on March 25, 2023.RetrievedAugust 20,2023.

- ^Burkhardt, Johanna; Lenhard, Wolfgang (2022). "A Meta-Analysis on the Longitudinal, Age-Dependent Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggression".Media Psychology.25(3): 499–512.doi:10.1080/15213269.2021.1980729.S2CID239233862.

- ^Kefalis, Chrysovalantis (2020)."The Effects of Video Games in Memory and Attention".International Journal of Educational Psychology.10(1): 51.doi:10.3991/ijep.v10i1.11290.S2CID211535998.

- ^Chaplin, Heather (March 12, 2007)."Is That Just Some Game? No, It's a Cultural Artifact".The New York Times.p. E7.Archivedfrom the original on December 4, 2015.

- ^Ransom-Wiley, James (March 12, 2007)."10 most important video games of all time, as judged by 2 designers, 2 academics, and 1 lowly blogger".Joystiq.AOL.Archivedfrom the original on March 14, 2007.RetrievedMarch 8,2016.

- ^Owens, Trevor (September 26, 2012)."Yes, The Library of Congress Has Video Games: An Interview with David Gibson".The Signal.Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2016.RetrievedMarch 8,2016.

- ^"Doom".The Strong National Museum of Play.The Strong.Archivedfrom the original on May 6, 2022.RetrievedMay 6,2022.

- ^"The Games".Next Generation.No. 4.Imagine Media.April 1995. p. 53.ISSN1078-9693.

- ^"Top 100 Video Games".Flux.No. 4. Harris Publications. April 1995. p. 25.ISSN1074-5602.

- ^"150 Best Games of All Time".Computer Gaming World.No. 148. November 1996. pp. 64–80.ISSN0744-6667.

- ^"The 15 Most Innovative Computer Games".Computer Gaming World.No. 148. November 1996. p. 102.ISSN0744-6667.

- ^"GameSpot's 100 Games of the Millennium".GameSpot.CBS Interactive.January 2, 2000. Archived fromthe originalon October 9, 2000.RetrievedSeptember 5,2022.

- ^"GameSpy's Top 50 Games of All Time".GameSpy.Ziff Davis.July 2001. Archived fromthe originalon July 10, 2010.RetrievedNovember 15,2005.

- ^Cork, Jeff (November 16, 2009)."Game Informer's Top 100 Games of All Time (Circa Issue 100)".Game Informer.GameStop.Archived fromthe originalon November 11, 2013.RetrievedDecember 10,2013.

- ^"GT Top Ten Breakthrough PC Games".GameTrailers.IGN.July 28, 2009. Archived fromthe originalon January 7, 2012.RetrievedJuly 27,2011.

- ^"The Top 200 Games of All Time".Game Informer.No. 200.GameStop.December 2009. pp. 44–79.ISSN1067-6392.

- ^"The All Time Top 100 Ever".GamesMaster.No. 21.Future.September 1994.ISSN0967-9855.

- ^"Top 100 Video Games of All Time".Hyper.No. 15.Nextmedia.February 1995.ISSN1320-7458.

- ^"The 50 Best Video games: A Legend In Your Own Living-Room".The Independent.February 6, 1999.Archivedfrom the original on October 18, 2017.RetrievedMay 5,2022.

- ^"We rank the 100 greatest videogames".Entertainment Weekly.Dotdash Meredith.May 13, 2003.ISSN1049-0434.Archivedfrom the original on March 9, 2018.RetrievedMarch 8,2018.

- ^"GamesTM Top 100".GamesTM.No. 100.Future.October 2010.ISSN1478-5889.

- ^"Les 100 meilleurs jeux de tous les temps".Jeuxvideo.com(in French).Webedia.March 4, 2011.Archivedfrom the original on June 27, 2018.RetrievedMarch 5,2019.

- ^"Gamereactor's Top 100 bedste spil nogensinde".Gamereactor(in Danish). January 16, 2017.Archivedfrom the original on May 28, 2022.RetrievedMay 28,2022.

- ^Peckham, Matt; Eadicicco, Lisa; Fitzpatrick, Alex; Vella, Matt; Patrick Pullen, John; Raab, Josh; Grossman, Lev (August 23, 2016)."The 50 Best Video Games of All Time".Time.Time Inc.ISSN0040-781X.Archivedfrom the original on August 30, 2016.RetrievedAugust 30,2016.

- ^"The 500 Best Video Games of All Time".Polygon.Vox Media.November 27, 2017.Archivedfrom the original on March 3, 2018.RetrievedDecember 1,2017.

- ^"20 best video games of all time — ranked by an expert jury".The Times.February 26, 2023.Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2023.RetrievedMarch 4,2023.

- ^Jensen, K. Thor (October 11, 2017)."The Complete History Of First-Person Shooters".PC Gamer.Future.Archivedfrom the original on June 12, 2020.RetrievedMay 31,2022.

- ^"The 50 Best Games Ever".PC Gamer US.5(10).Future:86–130. October 1998.ISSN1080-4471.

- ^Orland, Kyle (March 7, 2012)."Attacking the clones: indie game devs fight blatant rip-offs".Ars Technica.Condé Nast.Archivedfrom the original on June 14, 2023.RetrievedJune 13,2023.

- ^abcdTurner, Benjamin; Bowen, Kevin (December 11, 2003)."Bringin' in the Doom Clones".GameSpy.IGN.Archived fromthe originalon July 12, 2012.RetrievedFebruary 19,2009.

- ^Kohler, Chris (December 10, 1993)."Q&A: Doom's Creator Looks Back on 20 Years of Demonic Mayhem".Wired.Condé Nast.Archivedfrom the original on April 22, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^House, Michael L."Chex Quest – Overview".AllGame.All Media Network. Archived fromthe originalon November 17, 2014.RetrievedJuly 27,2011.

- ^Turi, Tim (February 27, 2015)."Doom Clone Troopers – The Story Behind Star Wars: Dark Forces".Game Informer.GameStop.Archived fromthe originalon June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^Zak, Robert (April 13, 2016)."Blood, Sweat & Laughter: The Beauty Of The Build Engine".Rock Paper Shotgun.Gamer Network.Archivedfrom the original on May 28, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^Kushner,pp. 180–182

- ^Pitta, Julia (March 23, 1995)."News Analysis: Playing the Interactive Game".Los Angeles Times.Archivedfrom the original on September 2, 2017.

- ^O'Connell,p. 50

- ^ab"Master Levels for Doom II".Steam.Valve.Archivedfrom the original on July 7, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 23,2018.

- ^"Final Doom".Electronic Gaming Monthly.No. 87.Ziff Davis.October 1996. p. 55.ISSN1058-918X.

- ^"Review Crew: Final Doom".Electronic Gaming Monthly.No. 89.Ziff Davis.December 1996. p. 88.ISSN1058-918X.

- ^Siegler, Joe (2000)."Tech Support: Commander Keen".3D Realms.Archivedfrom the original on June 2, 2016.RetrievedJune 13,2016.

- ^"Doom 3 – PC".IGN.Ziff Davis.Archivedfrom the original on April 30, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 3,2018.

- ^"Doom – PC".IGN.Ziff Davis.Archivedfrom the original on December 13, 2017.RetrievedJanuary 4,2018.

- ^Gonzales, Oscar (March 18, 2020)."Doom Eternal pushed to March 2020".CNET.Red Ventures.Archivedfrom the original on October 8, 2019.RetrievedMarch 21,2022.

- ^Zwiezen, Zack (April 24, 2021)."Let's Rank All The Doom Games, From Worst To Best".Kotaku.G/O Media.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^Cobbett, Richard (January 4, 2020)."Doom may be a classic, but were the novels?".PC Gamer.Future.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^Plunkett, Luke (February 13, 2017)."Doom: The Board Game: The Kotaku Review".Kotaku.G/O Media.Archivedfrom the original on November 15, 2021.RetrievedNovember 15,2021.

- ^Nunneley-Jackson, Stephany (March 12, 2019)."Doom makers distance themselves from Doom: Annihilation movie".VG247.Gamer Network.Archivedfrom the original on June 21, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^abcKushner,p. 171

- ^"The ESRB is Turning 20 – IGN".IGN.Ziff Davis.September 16, 2014.Archivedfrom the original on February 16, 2016.RetrievedFebruary 10,2016.

- ^"ESRB Game Ratings: Search Results: Doom".Entertainment Software Rating Board.Archived fromthe originalon February 16, 2006.RetrievedDecember 4,2004.

- ^Brown, Mark (September 1, 2011)."Germany Lifts 17-Year Ban on Demon-Blaster Doom".Wired.Condé Nast.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^Richtel, Matt (April 29, 1999)."Game Makers on the Defensive After the Columbine Shootings".The New York Times.p. G3.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 15,2023.

- ^Whitaker, Ron (June 1, 2015)."8 of the Most Controversial Videogames Ever Made".The Escapist.Gamurs.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 14,2023.

- ^abMikkelson, Barbara (January 1, 2005)."Columbine Doom Levels".Snopes.Archivedfrom the original on November 22, 2021.RetrievedJune 11,2020.

- ^Irvine, Reed; Kincaid, Cliff (1999)."Video Games Can Kill".Accuracy in Media.Archived fromthe originalon October 5, 2007.RetrievedNovember 15,2005.

- ^abcShoemaker, Brad (February 2, 2006)."The Greatest Games of All Time: Doom".GameSpot.SpotMedia Communications.Archivedfrom the original on October 9, 2017.RetrievedJune 21,2023.

- ^Gestalt (December 29, 1999)."Games of the Millennium".Eurogamer.Gamer Network.Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2016.RetrievedJune 16,2015.

- ^abcdKushner,pp. 167–169

- ^Hrodey, matt (February 11, 2019)."A Brief History of Doom Mapping".The Escapist.Gamurs.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 19,2023.

- ^Yang, Robert (September 19, 2012)."A People's History Of The FPS, Part 1: The WAD".Rock Paper Shotgun.Gamer Network.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 19,2023.

- ^Jay; Dee (May 1995). "Eye of the Monitor: D!Zone".Dragon.No. 217.TSR.pp. 67–74.ISSN1062-2101.

- ^Kushner,p. 212

- ^Tarason, Dominic (November 25, 2019)."The best Doom mods of 2019".Rock Paper Shotgun.Gamer Network.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 19,2023.

- ^Frank, Allegra (April 26, 2016)."John Romero's new Doom level is a tease for his next project".Polygon.Vox Media.Archivedfrom the original on July 4, 2016.RetrievedJuly 15,2016.

- ^Frank, Allegra (January 15, 2016)."You can download John Romero's first new Doom level in 21 years right now".Polygon.Vox Media.Archivedfrom the original on October 14, 2016.RetrievedOctober 14,2016.

- ^"Download Sigil".Romero Games.May 31, 2019.Archivedfrom the original on January 22, 2021.RetrievedJuly 24,2020.

- ^Wales, Matt (May 31, 2019)."John Romero's free, unofficial fifth Doom episode Sigil is finally here".Eurogamer.Gamer Network.Archivedfrom the original on June 20, 2023.RetrievedJune 19,2023.

- ^"Download Sigil II with Thorr Soundtrack".Romero Games.December 10, 2023.RetrievedDecember 10,2023.

- ^abSnyderpp. 34–36

- ^Lenti, Erica (July 10, 2021)."Why Do Gamers Love Speedrunning So Much Anyway?".Wired.Condé Nast.Archivedfrom the original on July 10, 2021.RetrievedJuly 10,2021.

- ^Paez, Danny (March 10, 2020)."Coined: How" speedrunning "became an Olympic-level gaming competition".Inverse.Bustle Digital Group.Archivedfrom the original on October 26, 2021.RetrievedMarch 18,2022.

- ^Turner, Benjamin (August 10, 2005)."Smashing the Clock".1Up.com.Ziff Davis.Archived fromthe originalon September 27, 2007.RetrievedAugust 13,2005.

- ^Walker, Alex (April 9, 2019)."Insanely Difficult Doom Record Beaten After 20 Years".Kotaku.G/O Media.Archivedfrom the original on April 23, 2023.RetrievedJune 21,2023.

- ^Hawkins, Josh (April 10, 2019)."22-year-old Doom E1M1: Hangar speedrun record finally broken".Shacknews.Gamerhub.Archivedfrom the original on October 28, 2020.RetrievedJune 21,2023.

- ^Stanton, Rich (September 7, 2022)."This Doom 'speedrun' took more than three weeks".PC Gamer.Future.Archivedfrom the original on June 22, 2023.RetrievedJune 21,2023.

Sources

[edit]- Consalvo, Mia (2016).Atari to Zelda: Japan's Videogames in Global Contexts.MIT Press.ISBN978-0-262-03439-5.

- Donovan, Tristan (2010).Replay: The History of Video Games.Yellow Ant.ISBN978-0-9565072-0-4.

- Dunnigan, James F.(2000).Wargames Handbook: How to Play and Design Commercial and Professional Wargames(3rd ed.).Writers Club Press.ISBN978-0-595-15546-0.

- Hawken, Kieren (2017).The A-Z of Atari Jaguar Games – Volume 1.Andrews UK.ISBN978-1-78538-734-0.

- King, Brad; Borland, John (2014).Dungeons & Dreamers: A Story of how Computer Games Created a Global Community(2nd ed.).ETC Press.ISBN978-0-9912227-2-8.

- Kushner, David(2004).Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture.Random House.ISBN978-0-8129-7215-3.

- Mendoza, Jonathan (1994).The Official DOOM Survivor's Strategies and Secrets.Sybex.ISBN978-0-7821-1546-8.

- O'Connell, Brian (1999).Gen E: Generation Entrepreneur is Rewriting the Rules of Business.Entrepreneur Press.ISBN978-1-891984-07-5.

- Pinchbeck, Dan (2013).Doom: Scarydarkfast.University of Michigan Press.ISBN978-0-472-05191-5.

- Romero, John(2023).Doom Guy: Life in First Person.Harry N. Abrams.ISBN978-1-4197-5811-9.

- Slaven, Andy (2002).Video Game Bible, 1985-2002.Trafford Publishing.ISBN978-1-55369-731-2.

- Snyder, David (2017).Speedrunning: Interviews with the Quickest Gamers.McFarland & Company.ISBN978-1-4766-3076-2.

External links

[edit]- DoomatMobyGames

- The "Official" Doom FAQ

- Source codeforDoomon GitHub

- 1993 video games

- 32X games

- 3DO Interactive Multiplayer games

- Acorn Archimedes games

- Android (operating system) games

- Atari Jaguar games

- Censored video games

- Classic Mac OS games

- Commercial video games with freely available source code

- Cooperative video games

- Doom (franchise) games

- Doom engine games

- DOS games

- Fiction set on Mars' moons

- First-person shooter multiplayer online games

- First-person shooters

- Game Boy Advance games

- Games commercially released with DOSBox

- GT Interactive games

- Id Software games

- Imagineer games

- IOS games

- Mobile games

- Multiplayer and single-player video games

- Multiplayer null modem games

- Nintendo Switch games

- Obscenity controversies in video games

- PlayStation (console) games

- PlayStation 3 games

- PlayStation 4 games

- PlayStation 5 games

- Science fantasy video games

- Sega Saturn games

- Shareware games

- Split-screen multiplayer games

- Sprite-based first-person shooters

- Super FX games

- Super Nintendo Entertainment System games

- Video games about demons

- Video games about Satanism

- Video games designed by John Romero

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games scored by Bobby Prince

- Video games set in hell

- Video games set on Mars

- Video games with 2.5D graphics

- Video games with digitized sprites

- Williams video games

- Windows games

- World Video Game Hall of Fame

- Xbox 360 games

- Xbox 360 Live Arcade games

- Xbox Cloud Gaming games

- Xbox One games

- Xbox Series X and Series S games