Desktop environment

Incomputing,adesktop environment(DE) is an implementation of thedesktop metaphormade of a bundle of programs running on top of a computeroperating systemthat share a commongraphical user interface(GUI), sometimes described as agraphical shell.The desktop environment was seen mostly onpersonal computersuntil the rise ofmobile computing.Desktop GUIs help the user to easily access and edit files, while they usually do not provide access to all of the features found in the underlying operating system. Instead, the traditionalcommand-line interface(CLI) is still used when full control over the operating system is required.

A desktop environment typically consists oficons,windows,toolbars,folders,wallpapersanddesktop widgets(seeElements of graphical user interfacesandWIMP). A GUI might also providedrag and dropfunctionality and other features that make thedesktop metaphormore complete. A desktop environment aims to be an intuitive way for the user to interact with the computer using concepts which are similar to those used when interacting with the physical world, such as buttons and windows.

While the termdesktop environmentoriginally described a style of user interfaces following the desktop metaphor, it has also come to describe the programs that realize the metaphor itself.[1]This usage has been popularized by projects such as theCommon Desktop Environment,KDE,and GNOME.

Implementation

[edit]On a system that offers a desktop environment, awindow managerin conjunction with applications written using awidget toolkitare generally responsible for most of what the user sees. The window manager supports theuser interactionswith the environment, while the toolkit provides developers asoftware libraryforapplicationswith a unified look and behavior.

Awindowing systemof some sort generally interfaces directly with the underlyingoperating systemand libraries. This provides support for graphical hardware, pointing devices, and keyboards. The window manager generally runs on top of this windowing system. While the windowing system may provide some window management functionality, this functionality is still considered to be part of the window manager, which simply happens to have been provided by the windowing system.

Applications that are created with a particular window manager in mind usually make use of awindowing toolkit,generally provided with the operating system or window manager. A windowing toolkit gives applications access towidgetsthat allow the user to interact graphically with the application in a consistent way.

History and common use

[edit]The first desktop environment was created byXeroxand was sold with theXerox Altoin the 1970s. The Alto was generally considered by Xerox to be a personal office computer; it failed in the marketplace because of poor marketing and a very high price tag.[dubious–discuss][2]With theLisa,Appleintroduced a desktop environment on an affordablepersonal computer,which also failed in the market.

The desktop metaphor was popularized on commercialpersonal computersby the originalMacintoshfromApplein 1984, and was popularized further byWindowsfromMicrosoftsince the 1990s. As of 2014[update],the most popular desktop environments are descendants of these earlier environments, including theWindows shellused inMicrosoft Windows,and theAqua environmentused inmacOS.When compared with theX-baseddesktop environments available forUnix-likeoperating systems such asLinuxandBSD,theproprietarydesktop environments included with Windows and macOS have relatively fixed layouts and static features, with highly integrated "seamless" designs that aim to provide mostly consistent customer experiences across installations.

Microsoft Windows dominates in marketshare among personal computers with a desktop environment. Computers using Unix-like operating systems such as macOS, ChromeOS, Linux, BSD or Solaris are much less common;[3]however, as of 2015[update]there is a growing market for low-cost Linux PCs using theX Window SystemorWaylandwith a broad choice of desktop environments. Among the more popular of these are Google'sChromebooksandChromeboxes,Intel'sNUC,theRaspberry Pi,etc.[citation needed]

On tablets and smartphones, the situation is the opposite, with Unix-like operating systems dominating the market, including theiOS(BSD-derived),Android,Tizen,SailfishandUbuntu(all Linux-derived). Microsoft'sWindows phone,Windows RTandWindows 10are used on a much smaller number of tablets and smartphones. However, the majority of Unix-like operating systems dominant on handheld devices do not use the X11 desktop environments used by other Unix-like operating systems, relying instead on interfaces based on other technologies.

Desktop environments for the X Window System

[edit]

On systems running theX Window System(typically Unix-family systems such asLinux,the BSDs,and formalUNIXdistributions), desktop environments are much more dynamic and customizable to meet user needs. In this context, a desktop environment typically consists of several separate components, including awindow manager(such asMutterorKWin), afile manager(such asFilesorDolphin), a set ofgraphical themes,together withtoolkits(such asGTK+andQt) andlibrariesfor managing the desktop. All these individual modules can be exchanged and independently configured to suit users, but most desktop environments provide a default configuration that works with minimal user setup.

Some window managers—such asIceWM,Fluxbox,Openbox,ROX DesktopandWindow Maker—contain relatively sparse desktop environment elements, such as an integratedspatial file manager,while others likeevilwmandwmiido not provide such elements. Not all of the program code that is part of a desktop environment has effects which are directly visible to the user. Some of it may be low-level code.KDE,for example, provides so-calledKIOslaves which give the user access to a wide range of virtual devices. These I/O slaves are not available outside the KDE environment.

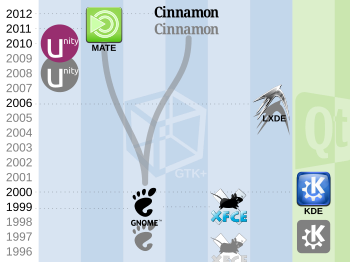

In 1996 theKDEwas announced, followed in 1997 by the announcement ofGNOME.Xfceis a smaller project that was also founded in 1996,[4]and focuses on speed and modularity, just likeLXDEwhich was started in 2006. Acomparison of X Window System desktop environmentsdemonstrates the differences between environments.GNOMEandKDEwere usually seen as dominant solutions, and these are still often installed by default on Linux systems. Each of them offers:

- To programmers, a set of standard APIs, a programming environment, andhuman interface guidelines.

- To translators, a collaboration infrastructure. KDE and GNOME are available in many languages.[5][6]

- To artists, a workspace to share their talents.[7][8]

- To ergonomics specialists, the chance to help simplify the working environment.[9][10][11]

- To developers of third-party applications, a reference environment for integration. OpenOffice.org is one such application.[12][13]

- To users, a complete desktop environment and a suite of essential applications. These include a file manager, web browser, multimedia player, email client, address book, PDF reader, photo manager, and system preferences application.

In the early 2000s, KDE reached maturity.[14]The Appeal[15]and ToPaZ[16]projects focused on bringing new advances to the next major releases of both KDE and GNOME respectively. Although striving for broadly similar goals, GNOME and KDE do differ in their approach to user ergonomics. KDE encourages applications to integrate and interoperate, is highly customizable, and contains many complex features, all whilst trying to establish sensible defaults. GNOME on the other hand is more prescriptive, and focuses on the finer details of essential tasks and overall simplification. Accordingly, each one attracts a different user and developer community. Technically, there are numerous technologies common to all Unix-like desktop environments, most obviously theX Window System.Accordingly, thefreedesktop.orgproject was established as an informal collaboration zone with the goal being to reduce duplication of effort.

As GNOME and KDE focus on high-performance computers, users of less powerful or older computers often prefer alternative desktop environments specifically created for low-performance systems. Most commonly used lightweight desktop environments includeLXDEandXfce;they both useGTK+,which is the same underlying toolkit GNOME uses. TheMATEdesktop environment, a fork of GNOME 2, is comparable to Xfce in its use of RAM and processor cycles, but is often considered more as an alternative to other lightweight desktop environments.

For a while, GNOME and KDE enjoyed the status of the most popular Linux desktop environments; later, other desktop environments grew in popularity. In April 2011, GNOME introduced a new interface concept with itsversion 3,while a popular Linux distributionUbuntuintroduced its own new desktop environment,Unity.Some users preferred to keep the traditional interface concept ofGNOME 2,resulting in the creation ofMATEas a GNOME 2 fork.[17]

Examples of desktop environments

[edit]The most common desktop environment on personal computers isWindows ShellinMicrosoft Windows.Microsoft has made significant efforts in making Windows shell visually pleasing. As a result, Microsoft has introducedtheme supportinWindows 98,the variousWindows XP visual styles,theAerobrand inWindows Vista,theMicrosoft design language(codenamed "Metro" ) inWindows 8,and theFluent Design SystemandWindows SpotlightinWindows 10.Windows shell can be extended viaShell extensions.

Many mainstream desktop environments for Unix-like operating systems, includingKDE,GNOME,Xfce,andLXDE,use the X Window System orWayland,any of which may be selected by users, and are not tied exclusively to the operating system in use. The desktop environment formacOS,which is also a Unix-like system, isAqua,which uses theQuartzgraphics layer, rather than using X or Wayland.

A number of other desktop environments also exist, including (but not limited to)CDE,EDE,GEM,IRIX Interactive Desktop,Sun'sJava Desktop System,Jesktop,Mezzo,Project Looking Glass,ROX Desktop,UDE,Xito,XFast. Moreover, there exists FVWM-Crystal, which consists of a powerful configuration for theFVWMwindow manager, a theme and further adds, altogether forming a "construction kit" for building up a desktop environment.

X window managersthat are meant to be usable stand-alone — without another desktop environment — also include elements reminiscent of those found in typical desktop environments, most prominentlyEnlightenment.[citation needed]Other examples includeOpenBox,Fluxbox,WindowLab,Fvwm,as well asWindow MakerandAfterStep,which both feature theNeXTSTEPGUIlook and feel. However newer versions of some operating systems make self configure.[clarification needed]

TheAmigaapproach to desktop environment was noteworthy: the originalWorkbenchdesktop environment inAmigaOSevolved through time to originate an entire family of descendants and alternative desktop solutions. Some of those descendants are the Scalos,[18]theAmbientdesktop ofMorphOS,and theWandererdesktop of theAROSopen source OS. WindowLab also contains features reminiscent of the Amiga UI. Third-partyDirectory Opussoftware, which was originally just anavigational file managerprogram, evolved to become a complete Amiga desktop replacement called Directory Opus Magellan.

OS/2(and derivatives such aseComStationandArcaOS) use theWorkplace Shell.Earlier versions of OS/2 used thePresentation Manager.

TheBumpTopproject was an experimental desktop environment. Its main objective is to replace the 2D paradigm with a "real-world" 3D implementation, where documents can be freely manipulated across a virtual table.

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]- Wayland– an alternative to the X Window System which can run several different desktop environments

- Comparison of X Window System desktop environments

References

[edit]- ^"Window managers and desktop environments – Linux 101".clemsonlinux.org.Archived fromthe originalon 2008-07-04.

- ^Lineback, Nathan."The Xerox Alto".Toastytech.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-07-04.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^"Operating System Market Share".Marketshare.hitslink.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-03-04.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^Then, Ewdison (6 February 2009),Xfce creator talks Linux, Moblin, netbooks and open-source,SlashGear,archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2011,retrieved5 February2011

- ^"KDE Localization".L10n.kde.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2013-04-21.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^"GNOME Internationalization".Gnome.org. 2011-10-23.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-03-14.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^Link 27 Dec Personalized Golf Ball Sign» (2011-12-27)."Where life imitates art".KDE-Artists. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-02-07.Retrieved2012-02-04.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^"GNOME Art: Artwork and Themes".Art.gnome.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2007-03-11.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^"OpenUsability".OpenUsability.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-02-04.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^GNOME Human Interface GuidelinesArchivedFebruary 1, 2004, at theWayback Machine

- ^KDE User Interface GuidelinesArchivedJanuary 6, 2004, at theWayback Machine

- ^"KDE OpenOffice.org".KDE OpenOffice.org. Archived fromthe originalon 2010-07-13.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^"GNOME OpenOffice.org".Gnome.org.Archivedfrom the original on 2008-10-18.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^"Linux Usability Report v1.01"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-19.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^"Appeal".KDE.Archived fromthe originalon 2007-01-06.

- ^"GNOME 3.0".GNOMEwiki.Archivedfrom the original on 2012-10-30.Retrieved2012-02-04.

- ^Thorsten Leemhuis (usinglinux1173.blogspot.com), August 5, 2012:Comment: Desktop Fragmentation

- ^Chris Haynes."Scalos – The Amiga Desktop Replacement".Scalos.noname.fr. Archived fromthe originalon 2018-09-22.Retrieved2012-02-04.