Diatomic carbon

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Diatomic carbon

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Ethenediylidene (substitutive) Dicarbon(C—C) (additive) | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| 196 | |

PubChemCID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard(EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C2 | |

| Molar mass | 24.022g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in theirstandard state(at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

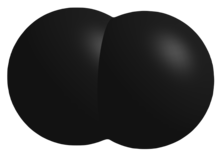

Diatomic carbon(systematically nameddicarbonand1λ2,2λ2-ethene), is a green, gaseousinorganicchemicalwith thechemical formulaC=C (also written [C2] or C2). It is kinetically unstable at ambient temperature and pressure, being removed throughautopolymerisation.It occurs in carbon vapor, for example inelectric arcs;incomets,stellar atmospheres,and theinterstellar medium;and in bluehydrocarbonflames.[1] Diatomic carbon is the second simplest of theallotropes of carbon(afteratomic carbon), and is an intermediate participator in the genesis offullerenes.

Properties

[edit]C2is a component of carbon vapor. One paper estimates that carbon vapor is around 28% diatomic,[2]but theoretically this depends on the temperature and pressure.

Electromagnetic properties

[edit]The electrons in diatomic carbon are distributed among the molecular orbitals according to theAufbau principleto produce unique quantum states, with corresponding energy levels. The state with the lowest energy level, or ground state, is a singlet state (1Σ+

g), which is systematically named ethene-1,2-diylidene or dicarbon(0•). There are several excited singlet and triplet states that are relatively close in energy to the ground state, which form significant proportions of a sample of dicarbon under ambient conditions. When most of these excited states undergo photochemical relaxation, they emit in the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum. However, one state in particular emits in the green region. That state is a triplet state (3Πg), which is systematically named ethene-μ,μ-diyl-μ-ylidene or dicarbon(2•). In addition, there is an excited state somewhat further in energy from the ground state, which only form a significant proportion of a sample of dicarbon under mid-ultraviolet irradiation. Upon relaxation, this excited state fluoresces in the violet region and phosphoresces in the blue region. This state is also a singlet state (1Πg), which is also named ethene-μ,μ-diyl-μ-ylidene or dicarbon(2•).

State Excitation

enthalpy

(kJ mol−1)Relaxation

transitionRelaxation

wavelengthRelaxation EM-region X1Σ+

g0 – – – a3Π

u8.5 a3Π

u→X1Σ+

g14.0 μm Long-wavelength infrared b3Σ−

g77.0 b3Σ−

g→a3Π

u1.7 μm Short-wavelength infrared A1Π

u100.4 A1Π

u→X1Σ+

g

A1Π

u→b3Σ−

g1.2 μm

5.1 μmNear infrared

Mid-wavelength infraredB1Σ+

g? B1Σ+

g→A1Π

u

B1Σ+

g→a3Π

u?

??

?c3Σ+

u159.3 c3Σ+

u→b3Σ−

g

c3Σ+

u→X1Σ+

g

c3Σ+

u→B1Σ+

g1.5 μm

751.0 nm

?Short-wavelength infrared

Near infrared

?d3Π

g239.5 d3Π

g→a3Π

u

d3Π

g→c3Σ+

u

d3Π

g→A1Π

u518.0 nm

1.5 μm

860.0 nmGreen

Short-wavelength infrared

Near infraredC1Π

g409.9 C1Π

g→A1Π

u

C1Π

g→a3Π

u

C1Π

g→c3Σ+

u386.6 nm

298.0 nm

477.4 nmViolet

Mid-ultraviolet

Blue

Molecular orbital theoryshows that there are two sets of paired electrons in a degenerate pi bonding set of orbitals. This gives a bond order of 2, meaning that there should exist a double bond between the two carbon atoms in a C2molecule.[3]One analysis suggested instead that aquadruple bondexists,[4]an interpretation that was disputed.[5]CASSCFcalculations indicate that the quadruple bond based on molecular orbital theory is also reasonable.[3]Bond dissociation energies(BDE) ofB2,C2,andN2show increasing BDE, indicatingsingle,double,andtriple bonds,respectively.

In certain forms of crystalline carbon, such as diamond and graphite, a saddle point or "hump" occurs at the bond site in the charge density. The triplet state of C2does follow this trend. However, the singlet state of C2acts more likesiliconorgermanium;that is, the charge density has a maximum at the bond site.[6]

Reactions

[edit]Diatomic carbon will react withacetoneandacetaldehydeto produceacetyleneby two different pathways.[2]

- TripletC2molecules will react through an intermolecular pathway, which is shown to exhibit diradical character. The intermediate for this pathway is the ethylene radical. Its abstraction is correlated with bond energies.[2]

- SingletC2molecules will react through an intramolecular, nonradical pathway in which two hydrogen atoms will be taken away from one molecule. The intermediate for this pathway is singletvinylidene.The singlet reaction can happen through a 1,1-diabstraction or a 1,2-diabstraction. This reaction is insensitive to isotope substitution. The different abstractions are possibly due to the spatial orientations of the collisions rather than the bond energies.[2]

- Singlet C2will also react withalkenes.Acetylene is a main product; however, it appears C2will insert into carbon-hydrogen bonds.

- C2is 2.5 times more likely to insert into amethyl groupas intomethylene groups.[7]

- There is a disputed possible room-temperature chemical synthesis via alkynyl-λ3-iodane.[8][9]

History

[edit]

The light of gas-rich comets mainly originates from the emission of diatomic carbon. An example isC/2014 Q2 (Lovejoy),where there are several lines of C2light, mostly in thevisible spectrum,[10]forming theSwan bands.[11] C/2022 E3 (ZTF),visible in early 2023, also exhibits green color due to the presence of diatomic carbon.[12]

See also

[edit]- Acetylide– a related chemical with the formulaC2−

2

References

[edit]- ^Hoffmann, Roald(1995)."Marginalia: C2In All Its Guises "(PDF).American Scientist.83(4): 309–311.Bibcode:1995AmSci..83..309H.JSTOR29775475.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2023-03-21.Retrieved2017-07-22.

- ^abcdSkell, Philip S.;Plonka, James H. (1970). "Chemistry of the singlet and triplet C2molecules. Mechanism of acetylene formation from reaction with acetone and acetaldehyde ".Journal of the American Chemical Society.92(19): 5620–5624.doi:10.1021/ja00722a014.

- ^abZhong, Ronglin; Zhang, Min; Xu, Hongliang; Su, Zhongmin (2016)."Latent harmony in dicarbon between VB and MO theories through orthogonal hybridization of 3σgand 2σu".Chemical Science.7(2): 1028–1032.doi:10.1039/c5sc03437j.PMC5954846.PMID29896370.

- ^Shaik, Sason; Danovich, David; Wu, Wei; Su, Peifeng;Rzepa, Henry S.;Hiberty, Philippe C. (2012). "Quadruple bonding in C2and analogous eight-valence electron species ".Nature Chemistry.4(3): 195–200.Bibcode:2012NatCh...4..195S.doi:10.1038/nchem.1263.PMID22354433.

- ^Grunenberg, Jörg (2012). "Quantum chemistry: Quadruply bonded carbon".Nature Chemistry.4(3): 154–155.Bibcode:2012NatCh...4..154G.doi:10.1038/nchem.1274.PMID22354425.

- ^Chelikowsky, James R.;Troullier, N.; Wu, K.; Saad, Y. (1994). "Higher-order finite-difference pseudopotential method: An application to diatomic molecules".Physical Review B.50(16): 11356–11364.Bibcode:1994PhRvB..5011355C.doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.50.11355.PMID9975266.

- ^Skell, P. S.;Fagone, F. A.; Klabunde, K. J. (1972). "Reaction of Diatomic Carbon with Alkanes and Ethers/ Trapping of Alkylcarbenes by Vinylidene".Journal of the American Chemical Society.94(22): 7862–7866.doi:10.1021/ja00777a032.

- ^Miyamoto, Kazunori; Narita, Shodai; Masumoto, Yui; Hashishin, Takahiro; Osawa, Taisei; Kimura, Mutsumi; Ochiai, Masahito; Uchiyama, Masanobu (2020-05-01)."Room-temperature chemical synthesis of C 2".Nature Communications.11(1): 2134.Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.2134M.doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16025-x.ISSN2041-1723.PMC7195449.PMID32358541.

- ^Rzepa, Henry S. (2021-02-23)."A thermodynamic assessment of the reported room-temperature chemical synthesis of C 2".Nature Communications.12(1): 1241.Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.1241R.doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21433-8.ISSN2041-1723.PMC7902603.PMID33623013.

- ^Venkataramani, Kumar; Ghetiya, Satyesh; Ganesh, Shashikiran; et, al. (2016)."Optical spectroscopy of comet C/2014 Q2 (Lovejoy) from the Mount Abu Infrared Observatory".Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.463(2): 2137–2144.arXiv:1607.06682.Bibcode:2016MNRAS.463.2137V.doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1820.

- ^Mikuz, Herman; Dintinjana, Bojan (1994)."CCD Photometry of Comets".International Comet Quarterly.RetrievedOctober 26,2006.

- ^Georgiou, Aristos (2023-01-10)."What makes the green comet green?".Newsweek.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-01-25.Retrieved2023-01-25.