Dicynodontia

| Dicynodontia | |

|---|---|

| |

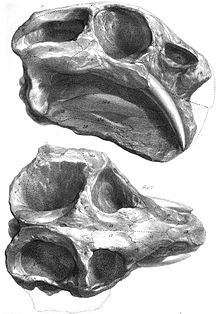

| Skeleton ofDiictodon | |

| |

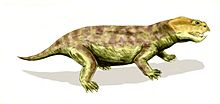

| Skeleton ofPlacerias | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Chainosauria |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia Owen,1859 |

| Clades & genera | |

|

see "Taxonomy" | |

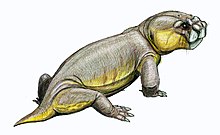

Dicynodontiais an extinctcladeofanomodonts,an extinct type of non-mammaliantherapsid.Dicynodonts wereherbivoresthat typically bore a pair of tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. Members of the group possessed a horny, typically toothless beak, unique amongst allsynapsids.Dicynodonts first appeared in Southern Pangaea during themid-Permian,ca. 270–260 million years ago, and became globally distributed and the dominant herbivorous animals in theLate Permian,ca. 260–252 Mya. They were devastated by theend-Permian Extinctionthat wiped out most other therapsids ca. 252 Mya. They rebounded during theTriassicbut died out towards the end of that period. They were the most successful and diverse of the non-mammalian therapsids, with over 70generaknown, varying from rat-sizedburrowersto elephant-sizedbrowsers.

Characteristics

[edit]

The dicynodontskullis highly specialised, light but strong, with thesynapsidtemporal openings at the rear of the skull greatly enlarged to accommodate larger jaw muscles. The front of the skull and the lower jaw are generally narrow and, in all but a number of primitive forms, toothless. Instead, the front of the mouth is equipped with a horny beak, as inturtlesandceratopsiandinosaurs.Food was processed by the retraction of the lower jaw when the mouth closed, producing a powerful shearing action,[2]which would have enabled dicynodonts to cope with tough plant material. Dicynodonts typically had a pair of enlarged maxillary caniniform teeth, analogous to thetuskspresent in some living mammals. In the earliest genera, they were merely enlarged teeth, but in later forms they independently evolved into ever-growing teeth like mammal tusks multiple times.[3]In some dicynodonts, the presence of tusks has been suggested to besexually dimorphic.[4]Some dicynodonts such asStahleckerialacked true tusks and instead bore tusk-like extensions on the side of the beak.[5][6]: 139

The body is short, strong and barrel-shaped, with strong limbs. In large genera (such asDinodontosaurus) the hindlimbs were held erect, but the forelimbs bent at the elbow. Both thepectoral girdleand theiliumare large and strong. The tail is short.[citation needed]

Pentasauropusdicynodont tracks suggest that dicynodonts had fleshy pads on their feet.[7]Mummified skin from specimens ofLystrosaurusin South Africa have numerous raised bumps.[8]

Endothermy and soft tissue anatomy

[edit]Dicynodonts have long been suspected of beingwarm-bloodedanimals. Their bones are highly vascularised and possessHaversian canals,and their bodily proportions are conducive to heat preservation.[9]In young specimens, the bones are so highly vascularised that they exhibit higher channel densities than most other therapsids.[10]Yet, studies onLate Triassicdicynodontcoprolitesparadoxically showcase digestive patterns more typical of animals with slow metabolisms.[11]

More recently, the discovery ofhairremnants inPermiancoprolitespossibly vindicates the status of dicynodonts as endothermic animals. As these coprolites come from carnivorous species and digested dicynodont bones are abundant, it has been suggested that at least some of these hair remnants come from dicynodont prey.[12]A new study using chemical analysis seemed to suggest that cynodonts and dicynodonts both developed warm blood independently before the Permian extinction.[13]

History

[edit]

A 2024 paper posited thatrock artof a superficially walrus-like imaginary creature with downcurved tusks created by theSan peopleofSouth Africaprior to 1835 may have been partly inspired by fossil dicynodont skulls which erode out of rocks in the area.[14]

Dicynodonts have been known to science since the mid-1800s. The South African geologistAndrew Geddes Baingave the first description of dicynodonts in 1845. At the time, Bain was a supervisor for the construction of military roads under theCorps of Royal Engineersand had found many reptilian fossils during his surveys of South Africa. Bain described these fossils in an 1845 letter published inTransactions of the Geological Society of London,calling them "bidentals" for their two prominent tusks.[15]In that same year, the English paleontologistRichard Owennamed two species of dicynodonts from South Africa:Dicynodon lacerticepsandDicynodon bainii.Since Bain was preoccupied with the Corps of Royal Engineers, he wanted Owen to describe his fossils more extensively. Owen did not publish a description until 1876 in hisDescriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum.[16]By this time, many more dicynodonts had been described. In 1859, another important species calledPtychognathus decliviswas named from South Africa. In the same year, Owen named the group Dicynodontia.[17]In hisDescriptive and Illustrated Catalogue,Owen honored Bain by erectingBidentaliaas a replacement name for his Dicynodontia.[16]The name Bidentalia quickly fell out of use in the following years, replaced by popularity of Owen's Dicynodontia.[18]

Evolutionary history

[edit]

Dicynodonts first appeared during theMiddle Permianin the Southern Hemisphere, with South Africa being the centre of their known diversity, and underwent a rapidevolutionary radiation,becoming globally distributed and amongst the most successful and abundant land vertebrates during theLate Permian.[19][20]During this time, they included a large variety of ecotypes, including large, medium-sized, and small herbivores and short-limbed mole-like burrowers.[21]

Only four lineages are known to have survived theGreat Dying;the first three represented with a single genus each:Myosaurus,Kombuisia,andLystrosaurus,the latter being the most common and widespread herbivores of theInduan(earliestTriassic). None of these survived long into the Triassic. The fourth group was theKannemeyeriiformes,the only dicynodonts who diversified during the Triassic.[22]These stocky, pig- to ox-sized animals were the most abundant herbivores worldwide from theOlenekianto theLadinianage. By theCarnianthey had been supplanted bytraversodontcynodonts andrhynchosaurreptiles. During theNorian(middle of the Late Triassic), perhaps due to increasing aridity, they drastically declined, and the role of large herbivores was taken over bysauropodomorphdinosaurs.[citation needed]

Fossils of anAsian elephant-sized dicynodontLisowiciabojanidiscovered inPolandindicate that dicynodonts survived at least until the late Norian or earliestRhaetian(latest Triassic); this animal was also the largest known dicynodont species.[23][24]

Six fragments of fossil bone discovered inQueensland,Australia, were interpreted as remains of a skull in 2003. This suggested to indicate that dicynodonts survived into theCretaceousin southernGondwana.[25]The dicynodont affinity of these specimens was questioned (including a proposal that they belonged to abaurusuchiancrocodyliform by Agnolin et al. in 2010),[26]and in 2019 Knutsen and Oerlemans considered this fossil to be ofPlio-Pleistoceneage, and reinterpreted it as a fossil of a large mammal, probably adiprotodontid.[27]

With the decline and extinction of the kannemeyerids, there were to be no more dominant large synapsid herbivores until the middlePaleoceneepoch (60 Ma) whenmammals,distant descendants ofcynodonts,began to diversify after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs.

Systematics

[edit]Taxonomy

[edit]Dicynodontia was originally named by the English paleontologistRichard Owen.It was erected as a family of the order Anomodontia and included the generaDicynodonandPtychognathus.Other groups of Anomodontia includedGnathodontia,which includedRhynchosaurus(now known to be anarchosauromorph) andCryptodontia,which includedOudenodon.Cryptodonts were distinguished from dicynodonts from their absence of tusks. Although it lacks tusks,Oudenodonis now classified as a dicynodont, and the name Cryptodontia is no longer used.Thomas Henry Huxleyrevised Owen's Dicynodontia as an order that includedDicynodonandOudenodon.[28]Dicynodontia was later ranked as a suborder or infraorder with the larger group Anomodontia, which is classified as an order. The ranking of Dicynodontia has varied in recent studies, with Ivakhnenko (2008) considering it a suborder, Ivanchnenko (2008) considering it an infraorder, and Kurkin (2010) considering it an order.[29]

Many higher taxa, including infraorders and families, have been erected as a means of classifying the large number of dicynodont species. Cluver and King (1983) recognised several main groups within Dicynodontia, including Eodicynodontia (containing onlyEodicynodon), Endothiodontia (containing onlyEndothiodontidae), Pristerodontia (Pristerodontidae,Cryptodontidae, Aulacephalodontidae,Dicynodontidae,Lystrosauridae,andKannemeyeriidae), Kingoriamorpha (containing onlyKingoriidae), Diictodontia (Diictodontidae,Robertiidae,Cistecephalidae,EmydopidaeandMyosauridae), andVenyukoviamorpha.[30]Most of these taxa are no longer considered valid. Kammerer and Angielczyk (2009) suggested that the problematic taxonomy and nomenclature of Dicynodontia and other groups results from the large number of conflicting studies and the tendency for invalid names to be mistakenly established.[18]

Phylogeny

[edit]Below is acladogrammodified from Angielczyk et al. (2021):[31]

| Dicynodontia | |

Current classification

[edit]- Dicynodontia

- Brachyprosopus

- Colobodectes

- Eodicynodon

- Lanthanostegus

- Nyaphulia

- Endothiodontia

- Eumantellidae

- Pylaecephalidae

- Therochelonia

- Emydopoidea

- Bidentalia

- Cryptodontia

- Dicynodontoidea

- Counillonia

- Taoheodon

- Daptocephalus

- Delectosaurus

- Dicynodon

- Dinanomodon

- Peramodon

- Elph

- Gordonia

- Interpresosaurus

- Katumbia

- Turfanodon

- Vivaxosaurus

- Lystrosauridae

- Kannemeyeriiformes

- Angonisaurus

- Dinodontosauridae

- Shansiodontidae

- Kannemeyeriidae

- Stahleckeriidae

- ?Sungeodon

- Woznikella

- Placeriinae

- Stahleckeriinae

South African geomyth

[edit]A horned serpent cave art is known from the La Belle France cave inSouth Africa,often conflated with theDingonek.It may be based on dicynodont fossils.[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Racki, Grzegorz; Lucas, Spencer G. (2018). "Timing of dicynodont extinction in light of an unusual Late Triassic Polish fauna and Cuvier's approach to extinction".Historical Biology.32(4): 1–11.doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1499734.S2CID91926999.

- ^Crompton, A. W.; Hotton, N. (1967). "Functional morphology of the masticatory apparatus of two dicynodonts (Reptilia, Therapsida)".Postilla.109:1–51.

- ^Whitney, M. R.; Angielczyk, K. D.; Peecook, B. R.; Sidor, C. A. (2021)."The evolution of the synapsid tusk: Insights from dicynodont therapsid tusk histology".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.288(1961).doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.1670.PMC8548784.PMID34702071.S2CID239890042.

- ^Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Benoit, Julien; Rubidge, Bruce S. (February 2021). Ruta, Marcello (ed.)."A new tusked cistecephalid dicynodont (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from the upper Permian upper Madumabisa Mudstone Formation, Luangwa Basin, Zambia".Papers in Palaeontology.7(1): 405–446.doi:10.1002/spp2.1285.ISSN2056-2799.S2CID210304700.

- ^Kammerer, Christian F.; Ordoñez, Maria de los Angeles (2021-06-01)."Dicynodonts (Therapsida: Anomodontia) of South America".Journal of South American Earth Sciences.108:103171.Bibcode:2021JSAES.10803171K.doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103171.ISSN0895-9811.S2CID233565963.

- ^Colbert, E. H.,(1969),Evolution of the Vertebrates,John Wiley & Sons Inc (2nd ed.)

- ^Citton, Paolo; Díaz-Martínez, Ignacio; de Valais, Silvina; Cónsole-Gonella, Carlos (7 August 2018)."Triassic pentadactyl tracks from the Los Menucos Group (Río Negro province, Patagonia Argentina): possible constraints on the autopodial posture of Gondwanan trackmakers".PeerJ.6:e5358.doi:10.7717/peerj.5358.PMC6086091.PMID30123702.

- ^Smith, Roger M.H.; Botha, Jennifer; Viglietti, Pia A. (October 2022)."Taphonomy of drought afflicted tetrapods in the Early Triassic Karoo Basin, South Africa".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.604:111207.Bibcode:2022PPP...60411207S.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111207.S2CID251781291.

- ^Bakker, Robert T. (April 1975). "Dinosaur renaissance".Scientific American.232(4): 58–79.Bibcode:1975SciAm.232d..58B.doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0475-58.

- ^Botha-Brink, Jennifer; Angielczyk, Kenneth D. (2010)."Do extraordinarily high growth rates in Permo-Triassic dicynodonts (Therapsida, Anomodontia) explain their success before and after the end-Permian extinction?".Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.160(2): 341–365.doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00601.x.

- ^Bajdek, Piotr; Owocki, Krzysztof; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (2014). "Putative dicynodont coprolites from the Upper Triassic of Poland".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.411:1–17.Bibcode:2014PPP...411....1B.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.06.013.

- ^Bajdek, Piotr; Qvarnström, Martin; Owocki, Krzysztof; Sulej, Tomasz; Sennikov, Andrey G.; Golubev, Valeriy K.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (2016). "Microbiota and food residues including possible evidence of pre-mammalian hair in Upper Permian coprolites from Russia".Lethaia.49(4): 455–477.doi:10.1111/let.12156.

- ^Rey, Kévin; Amiot, Romain; Fourel, François; Abdala, Fernando; Fluteau, Frédéric; Jalil, Nour-Eddine; Liu, Jun; Rubidge, Bruce S.; Smith, Roger MH; Steyer, J. Sébastien; Viglietti, Pia A; Wang, Xu; Lécuyer, Christophe (2017)."Oxygen isotopes suggest elevated thermometabolism within multiple Permo-Triassic therapsid clades".eLife.6:e28589.doi:10.7554/eLife.28589.PMC5515572.PMID28716184.

- ^Benoit, J (2024)."A possible later stone age painting of a dicynodont (Synapsida) from the South African Karoo".PLOS One.

- ^Bain, A.G. (1845)."On the discovery of fossil remains of bidental and other reptiles in South Africa".Transactions of the Geological Society of London.1:53–59.doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1845.001.01.72.hdl:2027/uc1.c034667778.S2CID128602890.

- ^abOwen, R. (1876).Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum.London: British Museum. p. 88.

- ^Owen, R. (1860). "On the orders of fossil and recent Reptilia, and their distribution in time".Report of the Twenty-Ninth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.1859:153–166.

- ^abKammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D. (2009)."A proposed higher taxonomy of anomodont therapsids"(PDF).Zootaxa.2018:1–24.

- ^Kurkin, A. A. (July 2011)."Permian anomodonts: Paleobiogeography and distribution of the group".Paleontological Journal.45(4): 432–444.doi:10.1134/S0031030111030075.ISSN0031-0301.S2CID129331000.

- ^Olroyd, Savannah L.; Sidor, Christian A. (August 2017)."A review of the Guadalupian (middle Permian) global tetrapod fossil record".Earth-Science Reviews.171:583–597.Bibcode:2017ESRv..171..583O.doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.07.001.ISSN0012-8252.

- ^Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Kammerer, Christian F. (2018). "5. Non-Mammalian synapsids: The deep roots of the mammalian family tree".Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics.pp. 117–198.doi:10.1515/9783110341553-005.ISBN9783110341553.S2CID92370138.

- ^Kammerer, Christian F.; Fröbisch, Jörg; Angielczyk, Kenneth D. (31 May 2013)."On the validity and phylogenetic position ofEubrachiosaurus browni,a kannemeyeriiform dicynodont (Anomodontia) from Triassic North America ".PLOS ONE.8(5): e64203.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864203K.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064203.PMC3669350.PMID23741307.

- ^Tomasz Sulej; Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki (2019)."An elephant-sized Late Triassic synapsid with erect limbs".Science.363(6422): 78–80.Bibcode:2019Sci...363...78S.doi:10.1126/science.aal4853.PMID30467179.

- ^St. Fleur, Nicholas (4 January 2019)."An Elephant-Size Relative of Mammals That Grazed Alongside Dinosaurs".The New York Times.Retrieved6 January2019.

- ^Thulborn, T.; Turner, S. (2003)."The last dicynodont: an Australian Cretaceous relict".Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.270(1518): 985–993.doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2296.JSTOR3558635.PMC1691326.PMID12803915.

- ^Agnolin, F. L.; Ezcurra, M. D.; Pais, D. F.; Salisbury, S. W. (2010)."A reappraisal of the Cretaceous non-avian dinosaur faunas from Australia and New Zealand: Evidence for their Gondwanan affinities"(PDF).Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.8(2): 257–300.doi:10.1080/14772011003594870.S2CID130568551.

- ^Espen M. Knutsen; Emma Oerlemans (2019). "The last dicynodont? Re-assessing the taxonomic and temporal relationships of a contentious Australian fossil".Gondwana Research.77:184–203.doi:10.1016/j.gr.2019.07.011.S2CID202908716.

- ^Osborn, H.F. (1904)."Reclassification of the Reptilia".The American Naturalist.38(446): 93–115.doi:10.1086/278383.S2CID84492986.

- ^Kurkin, A.A. (2010). "Late Permian dicynodonts of Eastern Europe".Paleontological Journal.44(6): 72–80.doi:10.1134/S0031030110060092.S2CID131459807.

- ^Cluver, M.A.; King, G.M. (1983). "A reassessment of the relationships of Permian Dicynodontia (Reptilia, Therapsida) and a new classification of dicynodont".Annals of the South African Museum.91:195–273.

- ^Angielczyk, K. D.; Liu, J.; Yang, W. (2021). "A Redescription ofKunpania scopulusa,a Bidentalian Dicynodont (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from the?Guadalupian of Northwestern China ".Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.41(1): e1922428.Bibcode:2021JVPal..41E2428A.doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1922428.S2CID236406006.

- ^Benoit J (2024) A possible later stone age painting of a dicynodont (Synapsida) from the South African Karoo. PLoS ONE 19(9): e0309908.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309908

Further reading

[edit]- Carroll, R. L.(1988),Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution,WH Freeman & Co.

- Cox, B., Savage, R.J.G., Gardiner, B., Harrison, C. and Palmer, D. (1988)The Marshall illustrated encyclopedia of dinosaurs & prehistoric animals,2nd Edition, Marshall Publishing

- King, Gillian M.,"Anomodontia" Part 17 C,Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology,Gutsav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart and New York, 1988

- King, Gillian M., 1990,The Dicynodonts: A Study in Palaeobiology,Chapman and Hall, London and New York