Discovery of Brazil

The first arrival of European explorers to the territory of present-dayBrazilis often understood as the sighting of the land later namedIsland of Vera Cruz,nearMonte Pascoal,by the fleet commanded by Portuguese navigatorPedro Álvares Cabral,on 22 April 1500. Cabral's voyage is part of the so-calledPortuguese discoveries.[1][2]

Although used almost exclusively in relation toPedro Álvares Cabral's voyage,the term "discovery of Brazil" can also refer to the arrival of the expedition led bySpanishnavigator and explorerVicente Yáñez Pinzón.He reached theCape of Santo Agostinho,a promontory located in the current state ofPernambuco,on 26 January 1500. This is the oldest confirmed European landing in Brazilian territory.[3][4]

The use of the term "discovery" for this historical event considers the viewpoint of peoples from Europe. They recorded it in the form ofwritten history,and the record expresses a Eurocentric conception of history.[5]

Discovery by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón

[edit]Many scholars assert that the real discoverer of Brazil was the Spanish navigatorVicente Yáñez Pinzón,who on 26 January 1500 landed at theCape of Santo Agostinho,on the southern coast ofPernambuco.This is considered the earliest documented European voyage to what is now Brazilian territory.[1][2][3][4]

The fleet, consisting of four caravels, set sail fromPalos de la Fronteraon 19 November 1499. After crossing theEquator,Pinzón encountered a severe storm. On 26 January 1500, he sighted the cape and anchored his ships in a sheltered port easily accessible to small boats, with a depth of 16 feet, as indicated by sounding. The mentioned port was the cove ofSuape,located on the southern slope of the promontory, which the Spanish expedition named Cape of Santa María de la Consolación. Spain did not claim the discovery, although it was meticulously recorded by Pinzón and documented by important chroniclers of the time such asPeter Martyr d'AnghieraandBartolomé de las Casas.Spain and Portugal had signed theTreaty of Tordesillasto divide their areas of influence in the New World, and this area was to be controlled by Portugal.[1][3][6][7]

During the night after the landing, the Spanish observed large fires burning in the distance, along the northwest coast. The following morning, they sailed in that direction until reaching a river, which Pinzón named "Rio Formoso".On the beach, along the riverbanks, their crew had a violent encounter with the local indigenous people (now known to have belonged to thePotiguara tribe), an event recorded by the Spanish chronicler.

Heading north, Pinzón rounded theCape of São Roqueand reached theAmazon Riverin February, which he named Santa María de la Mar Dulce. From there he continued to theGuianasand then to theCaribbean Seaand across the Atlantic. He reached Spain on 30 September 1500.

Pinzón's cousin,Diego de Lepe,undertook a parallel journey, departing from Palos in 1499, twenty days after Pinzón's fleet. Lepe arrived at the Cape of Santo Agostinho in February 1500, but sailed a few miles to the south, noting that the coast slanted markedly to the southwest. From there he followed the same route to the north and the Caribbean as had Pinzón.[1][3]

Themap by Juan de la Cosa,a chart made in 1500 at the request of the first kings of Spain–known as theCatholic Monarchs–shows the South American coast adorned with Spanish flags from theCape de la Vela(in present-dayColombia) to the easternmost point of the continent. The accompanying text reads, "Este cavo se descubrio en año de mily IIII X C IX por Castilla syendo descubridor vicentians"(lit. 'This cape was discovered in 1499 by Castile, with Vicente Yáñez as the discoverer'). This most likely refers to Pinzón's arrival at the Cape of Santo Agostinho in late January 1500.[8]

The map shows that further east, and separated from the mainland, is an island marked as discovered by Portugal, and colored in blue. De la Cosa probably intended to show the land discovered by Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500, which he named "Terra de Vera Cruz"or"de Santa Cruz".The Portuguese believed it to be an island (Island of Vera Cruz) lying in the Atlantic, separating Europe from the Indies.[8]

On 30 October 1500, kingManuel I of PortugalmarriedMaria of Aragon and Castile,daughter of the Catholic Monarchs and sister of his first wifeIsabella(who died during a difficult childbirth). This union initiated a deep dynastic connection between the Catholic nations of Portugal and Spain.

The following year, the first Portuguese expedition to explore the Brazilian coast departed from Lisbon, entrusted toAmerigo Vespucciand commanded byGonçalo Coelho.On 17 August 1501, the fleet sighted theCape of São Roquein present-dayRio Grande do Norte,already discovered by Pinzón (latitude calculations were relatively accurate at the time, although longitude was quite faulty). The Portuguese sailed southward, tracing the entire east coast of Brazil. NearSanta Cruz Cabrália,they encountered two exiles from Cabral's fleet, whom they rescued. They realized then that Cabral had not discovered an island, but a stretch of coastline of the new continent. The fleet sailed to theCape of Santa Mariain present-dayUruguay.

Later the Spanish Crown sent navigatorJuan Díaz de Solíson an expedition to explore the lands allocated to Spain according to the Treaty of Tordesillas–whose imaginary line passed along the coast of the present-day state ofSão Paulo,nearCananéia.[9][10][11]For his discovery of Brazil, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón was honored by KingFerdinand II of Aragonon 5 September 1501.[12]

Pedro Álvares Cabral's fleet

[edit]In order to seal the success ofVasco da Gama's voyage indiscovering the sea route to India–which allowed bypassing theMediterranean,then under the control of theMoorsand Italian nations–King Manuel Ihastened to outfit a new fleet for theIndies.Since Vasco da Gama's small fleet had struggled to establish itself and engage in trade, this would be the largest fleet assembled by the West up to that point. It comprised thirteen vessels and more than a thousand men. Except for the names of two ships and a caravel, the names of the other ships under Cabral's command are not known. It is estimated that the fleet carried provisions for about eighteen months.

This was the largest squadron ever sent to sail the Atlantic: ten ships, three caravels, and a supply ship. Although the name of the flagship is unknown, the vice-commander's ship of the fleet,Sancho de Tovar's ship, was namedEl-Rei.Another ship was theAnunciada,commanded byNuno Leitão da Cunha.This ship belonged toÁlvaro de Bragança,son ofthe Duke of Braganza,and was equipped with resources fromBartolomeo MarchionniandGirolamo Sernigi,Florentine bankers residing in Lisbon who invested in thespice trade.The bankers' letters exchanged with their Italian partners and shareholders preserved the ship's name. The caravel commanded byPero de Ataíde,wasSão Pedro.The name of the other caravel, commanded byBartolomeu Dias,is lost. The fleet was completed by a supply ship commanded byGaspar de Lemos.It was her responsibility to return to Portugal with news of the discovery of Brazil.

Based on an incomplete document found in theTorre do Tomboin Lisbon,Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagenidentified five of the ten ships that made up Cabral's fleet. They wereSanta Cruz,Vitória,Flor de la Mar,Espírito Santo,andEspera.Because the source cited by Varnhagen has never been found again, most historians prefer not to adopt the names he listed. The fleet remains largely anonymous.

Some 19th-century historians declared that Cabral's flagship was the legendarySão Gabriel,the same ship commanded by Vasco da Gama three years earlier, when he discovered the sea route to India. But no documentation has been found to support this theory.

Shortly before the fleet's departure, the King ordered amassto be said at theMonastery of Belém,presided over by theBishop of Ceuta,Diogo de Ortiz.He personally blessed a flag with the arms of the Kingdom and handed it to Cabral, bidding farewell to the nobleman and the remaining captains.

Vasco da Gama reportedly made recommendations for the impending long journey: stressing coordination among the ships in order to prevent their losing sight of each other. He recommended to the captain-general to fire the cannons twice and wait for the same response from all other ships before changing course or speed (a counting method still used in terrestrial battlefields), among other similar communication codes.

The arrival at Vera Cruz

[edit]On 24 April, Cabral, accompanied bySancho de Tovar,Simão de Miranda,Nicolau Coelho,Aires Correia,andPero Vaz de Caminha,received a group of indigenous people on his ship. They were described as recognizing the gold and silver displayed on the vessel–notably a gold thread and a silver candlestick. The Portuguese concluded that they were familiar with gold as a result of having much of it in their land. But in a letter, Caminha, wrote that he could not ascertain whether the natives were saying that there was gold there, or if the sailors' desire for it was so great they imagined a positive response from the natives. It was later proven that the crew had imagined a positive interpretation; the natives made no claims to gold.[13]

Caminha also recorded in aletterthe later violent encounter between Portuguese and indigenous people on the beach. The cultural shock for each side was evident. The indigenous people did not recognize the animals brought by the sailors, except for a parrot that the captain had with him. The sailors offered the natives food and wine which they did not recognize and rejected. They were curious about unfamiliar objects–such asRosary beads.The Portuguese were surprised that the natives appeared to recognize precious metals. Cabral had dressed in all the attire and adornments befitting a captain, to impress the indigenous people, and yet they passed by him without appearing to distinguish him from the other crew members.

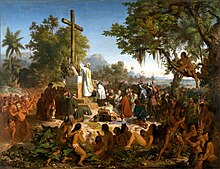

The indigenous people were curious about the newcomers and attended theFirst Mass,celebrated by FriarHenrique de Coimbra,on Sunday, 26 April 1500. The Portuguese liked to think they had introduced the natives to their faith. Shortly after the mass, Cabral's fleet set sail for theIndies,its ultimate destination. It sent one of the ships back to Portugal with Caminha's letter.

Later, when Portuguese fleets arrived with missionaries and colonists, it became obvious that they needed other methods to evangelize the indigenous people in earnest. The indigenous people had simply been curious about the ritual gestures and words of the Mass, with no real interest in the Catholic faith. They had their own religion.[citation needed]

- The sighting of the land and first mass in Brazil

-

Cabral sights the Brazilian mainland for the first time on 22 April 1500, painting by Aurélio de Figueiredo, 1900

-

The raising of the Cross in Porto Seguro, painting by Pedro Peres, 1879

-

The First Mass in Brazil,painting byVictor Meirelles,1860

The native peoples

[edit]

The peoples who inhabited Brazil at the time of Cabral's arrival are classified as living in theStone Agein terms of technology, transitioning from thePaleolithicto theNeolithic.They practiced an incipient form of agriculture (raisingcornandcassava) and animal domestication. (They ran wild pig andcapybara.) But they had developed extensive knowledge offermented alcoholic beverageproduction (more than 80 types), using roots, tubers, barks, and fruits, among other material, as raw ingredients.[14]

When the Portuguese arrived in Brazil, the coast of Bahia was occupied by two indigenous nations that each spokeTupilanguages: theTupinambá,who occupied the stretch betweenCamamuand the mouth of theSão Francisco River;and theTupiniquin,who had territory extending from Camamu to the border with the current Brazilian state ofEspírito Santo.Further inland, occupying the strip parallel to that appropriated by the Tupiniquin were theAimoré.

At the beginning ofthe colonization of Brazil,the Tupiniquin supported the Portuguese. Their rivals, the Tupinambá, supported the French. During the 16th and 17th centuries the French carried out various offensives againstPortuguese America.The presence of the Europeans and creation of new alliances fueled the hostile tensions between the two tribes.Hans Staden,a German traveler, documented what he observed of this during period of captivity among the Tupinambá. Both tribes practiced ritualcannibalismagainst their rivals, as a way both to honor and acquire power of their enemies. The Europeans were outraged and appalled by the practice, persecuting natives for their culture.

Date of discovery in Luso-Brazilian historiography

[edit]In historiographical terms, the date of the discovery of Brazil has varied over the centuries:[15]

- Until 1817–3 May (according toGaspar Correia)

- 1817–22 April (according to theletter of Pero Vaz de Caminha,which was published by FatherManuel Aires de Casalwho found it among the documents broughtto Brazil by the Royal Family in 1808)

- 1823–José Bonifácioproposed the date of the opening of theConstituent Assembly(3 May) to coincide with the date of the discovery (supposedly unaware of Caminha's letter published in 1817).

- From the second half of the 19th century until 1889, the educated Brazilian citizens knew that the date of the discovery was 22 April, although it was not part of the holidays of theEmpire.

- 1890–A republican decree established 3 May as a holiday commemorating the discovery. However, the press at the time already considered 22 April as the correct date.

- 1930–A decree byGetúlio Vargasabolished the holiday of 3 May. Since then, 22 April has been affirmed as the date.

Theories regarding the discovery of Brazil

[edit]There are several assumptions and hypotheses about the discovery of Brazil. The best-known one revolves around a possible secret expedition by the Portuguese navigatorDuarte Pacheco Pereirain 1498, aimed at identifying territories belonging to Portugal orCastileaccording to theTreaty of Tordesillasof 1494.Pereira participated in the treaty negotiations.[16][17]The hypothetical journey is solely based on the explorer's account inEsmeraldo de Situ Orbis(1505), a book he authored. However, the text is ambiguous: Pacheco Pereira explicitly states that the king of Portugal "ordered the discovery of the western part", suggesting he was not speaking of his own explorations but rather of everything already explored by various navigators and known by 1505. This view is supported by the latitudes and longitudes provided, ranging fromGreenlandto the current southern region ofBrazil.Furthermore, the possibility of a policy of secrecy by Portuguese monarchs, proposed in the first half of the 20th century by historianDamião Peres,is not sustainable, as it was common practice, in the absence of a treaty, to claim sovereignty over a land by publicizing its discovery.[17][18]

There is also suspicion that the Portuguese discovery of Brazil in 1500 may have been intentional, based on prior knowledge of the territory. As suggested by Pacheco Pereira inEsmeraldo de Situ Orbis,Portuguese navigators in 1498 were instructed byKing Manuel Ito explore the Atlantic in search of lands. Before heading toIndiaon the 1500 expedition,Pedro Álvares Cabralwould have deviated westward beyond necessity to verify the existence of territories as desired by the king. Upon sighting Brazil, Cabral believed he had discovered an island, thus invalidating the theory that he had knowledge of continental lands in those regions. The representation of the then-calledIsland of Vera CruzonJuan de la Cosa's map,made the same year, refutes another theory that Portuguese discoveries were secrets not shared with the Spanish. Despite the discovery, Cabral's voyage to India was considered a failure. Cabral received an annual pension of 30 thousandreaisfor his deedsmuch less than the 400 thousand reais given toVasco da Gamain 1498and was forgotten by the king, dying in obscurity around 1520. His tomb was ignored for three hundred years until it was located in 1839 by historianFrancisco Adolfo de Varnhagen.[8][18][19]

There are also theories challenging the locations sighted byVicente Yáñez Pinzónand Pedro Álvares Cabral. The first Brazilian historian to question the landing of the Spanish navigator at theCape of Santo Agostinhowas the Viscount of Porto Seguro, Francisco Varnhagen, in the mid-19th century.[20]Although Varnhagen acknowledged that Pinzón had been in Brazil before Cabral, he believed the Cape of Santa María de la Consolación to be the tip of Mucuripe in the city ofFortaleza.The thesis was accepted by AdmiralMax Justo Guedesbut contested by many historians.[21]For the Portuguese, such asDuarte Leite,the Spaniards would have landed north ofCape Orange,in present-dayFrench Guiana.[22]Regarding the location sighted by Pedro Álvares Cabral, there is a thesis advocating forPico do CabugiinRio Grande do Norteas the mountain described by Pero Vaz Caminha, and Praia do Marco as the point of arrival of Cabral's fleet. However, according to theCantino planisphere(1502), made the year following the exploratory expedition that rescued the two convicts left in Brazil by Cabral, the landing place of the Portuguese navigator is situated south of theBay of All Saints.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcdeHenri Beuchat (3 February 2024)."Manual de arqueología americana"(in Spanish). p. 77.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved23 April2019.

- ^ab"Pinzón ou Cabral: quem chegou primeiro ao Brasil?".G1. 14 October 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 15 October 2011.Retrieved5 April2017.

- ^abcdAntonio de Herrera y Tordesillas(3 February 2024)."Historia general de los hechos de los Castellanos en las islas y tierra firme de el Mar Oceano, Volume 2"(in Spanish). p. 348.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved22 April2019.

- ^ab"Martín Alonso Pinzón and Vicente Yáñez Pinzón".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 5 September 2015.Retrieved3 February2020.

- ^Maia, Fernando Joaquim Ferreira; Farias, Mayara Helenna Verissimo de (16 September 2020)."Colonialidade do poder: a formação do eurocentrismo como padrão de poder mundial por meio da colonização da América".Interações (Campo Grande)(in Portuguese): 588.doi:10.20435/inter.v21i3.2300.ISSN1984-042X.

- ^"Uma história do litoral pernambucano e o porto dos caminhos sinuosos"(PDF).Unicap.Archived(PDF)from the original on 14 April 2019.Retrieved14 April2019.

- ^"Geoparque Litoral Sul de Pernambuco – CPRM".Serviço Geológico do Brasil. Archived fromthe originalon 14 April 2019.Retrieved14 April2019.

- ^abcDAVIES, Arthur (1976)."The Date of Juan de la Cosa's World Map and Its Implications for American Discovery".The Geographical Journal.142(1): 111–116.Bibcode:1976GeogJ.142..111D.doi:10.2307/1796030.JSTOR1796030.págs. 111–116.Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023.Retrieved28 January2024.

- ^"D. Manuel I"(PDF).CM Mirandela.Archived(PDF)from the original on 1 May 2019.Retrieved1 May2019.

- ^Shozo Motoyama (3 February 2024).Prelúdio para uma história: ciência e tecnologia no Brasil.EdUSP.ISBN978-85-314-0797-0.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved1 May2019.

- ^"Bens tombados em Paranaguá"(PDF).Secretaria de Estado da Cultura do Paraná. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 7 January 2019.Retrieved1 May2019.

- ^"Capitulación otorgada a Vicente Yáñez Pinzón"(in Spanish). El Historiador.Archivedfrom the original on 23 April 2019.Retrieved23 April2019.

- ^Pereira, Paulo Roberto (org.).Os três únicos testemunhos do descobrimento do Brasil.In: CAMINHA, Pero Vaz de.Carta de Pero Vaz de Caminha.Rio de Janeiro: Nova Aguilar, 1999. pp.31–59.

- ^Cavalcante, Messias Soares.A verdadeira história da cachaça.São Paulo: Sá Editora, 2011. 608pp.ISBN9788588193628

- ^Mendonça, Alexandre Ribeiro de. 22 de Abril de 1500ː Descobrimento do Brasil ". inːJornal do Exército,n.º 662, Out. 2016, pp.38–43.

- ^Mota, Avelino Teixeira da.Duarte Pacheco Pereira, capitão e governador de S. Jorge da Mina.Mare Liberum, I(1990), pp.1–27.

- ^ab"O caso Pacheco Pereira".PÚBLICO. 13 October 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 6 April 2017.Retrieved5 April2017.

- ^abDuarte Pacheco Pereira (3 February 2024)."Esmeraldo de situ orbis".Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved29 April2019.

- ^"Varnhagen (1816–1878)"(PDF).Funag.Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 December 2019.Retrieved29 April2019.

- ^Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen (1858)."Examen de quelques points de l'histoire geographique du bresil comprenant des eclaircissements nouveaux sur le seconde voyage tentrionales du bresil par hojida et par pinzon, sur l'ouvrage de navarrete, sur la veritable ligne de demarcation de tordesillas, sur l'oyapoc ou vincent pinzon, sur le veritable point de vue ou doit se placer tout historien du bresil, etc, ou, analyse critique du rapport de m. d'avezac sur la recente histoire generale du bresil".Biblioteca Digital do Senado Federal (BDSF).Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2019.Retrieved24 April2019.

- ^"Cronologia de Fortaleza".Arquivo Nirez.Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2018.Retrieved24 April2019.

- ^"História dos descobrimentos: colectânea de esparsos, Volume 1".Edições Cosmos. 3 February 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2024.Retrieved24 April2019.

- ^"União para provar que Cabral chegou primeiro ao Rio Grande do Norte".O Globo. 21 April 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2019.Retrieved24 April2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Ab'Saber, Aziz N.et al.História geral da civilização brasileira. Tomo I: A época colonial – Administração, economia, sociedade.(1.º vol. 4.ª edição). São Paulo: Difusão Europeia do Livro, 1972. 399pp.

- Boxer, Charles R.O império marítimo português, 1415–1825,"O ouro da Guiné e Preste João (1415–99)". São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. pp.31–53.

- Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de.Visão do paraíso,"América Portuguesa e Índias de Castela". São Paulo: Editora Nacional, 1958.

- Léry, Jean de.Viagem à terra do Brasil,"Capítulo XV – De como os americanos tratam os prisioneiros de guerra e das cerimônias observadas ao matá-los e devorá-los". São Paulo: Editora Edusp, 1980. pp.193–204.

- Staden, Hans.Hans Staden: primeiros registros escritos e ilustrados sobre o Brasil e seus habitantes,"História verídica e descrição de uma terra de selvagens, nus e cruéis comedores de seres humanos...". São Paulo: Editora Terceiro Nome, 1999. pp.53–84.

External links

[edit] Media related toDiscovery of Brazilat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toDiscovery of Brazilat Wikimedia Commons Works related tothe letter of Pero Vaz de Caminhaat Wikisource

Works related tothe letter of Pero Vaz de Caminhaat Wikisource

- 1500 in Brazil

- 1500 in Portugal

- 1500 in Spain

- Age of Discovery

- Christianization

- History of Brazil

- History of European colonialism

- History of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- History of Portugal

- History of Spain

- Portuguese colonization of the Americas

- Portuguese exploration in the Age of Discovery

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Spanish exploration in the Age of Discovery

- Western culture