The Discoverie of Witchcraft

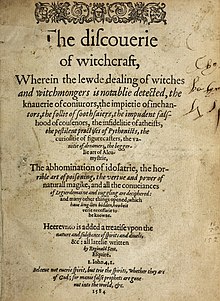

Title page of the first edition (1584) | |

| Author | Reginald Scot |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Published | 1584 |

| Publication place | England |

The Discoverie of Witchcraftis a book published by the English gentlemanReginald Scotin 1584, intended as an exposé of early modernwitchcraft.It contains a small section intended to show how the public was fooled by charlatans, which is considered the first published material on illusionary or stagemagic.

Scot believed that the prosecution of those accused of witchcraft was irrational and notChristian,and he held theRoman Churchresponsible. Popular belief held that all obtainable copies were burned on the accession ofJames Iin 1603.[1]

Publication

[edit]Scot's book appeared entitled"The Discoverie of Witchcraft, wherein the Lewde dealing of Witches and Witchmongers is notablie detected, in sixteen books... whereunto is added a Treatise upon the Nature and Substance of Spirits and Devils",1584. At the end of the volume the printer gives his name as William Brome.

There are four dedications: toSir Roger Manwood,chief baron of the exchequer; another to Scot's cousin, Sir Thomas Scot; a third jointly toJohn Coldwell,thendean of Rochester,and toWilliam Redman,thenArchdeacon of Canterbury;and a fourth "to the readers". Scott enumerates 212 authors whose works inLatinhe had consulted, and twenty-three authors who wrote in English. The names in the first list include many Greek and Arabic writers; among those in the second areJohn Bale,John Foxe,Sir Thomas More,John Record,Barnabe Googe,Abraham Fleming,andWilliam Lambarde.But Scot's information was not only from books. He had studied superstitions respecting witchcraft in courts of law in country districts, where the prosecution of witches was unceasing, and in village life, where the belief in witchcraft flourished in many forms.

He set himself to prove that the belief in witchcraft and magic was rejected by reason and by religion and that spiritualistic manifestations were wilful impostures or illusions due to mental disturbance in the observers. His aim was to prevent the persecution of poor, aged, and simple persons, who were popularly credited with being witches. The maintenance of the superstition he blamed largely on theRoman Catholic Church,and he attacked writers includingJean Bodin(1530–1596), author ofDémonomanie des Sorciers(Paris, 1580), andJacobus Sprenger,supposed joint author ofMalleus Maleficarum(Nuremberg, 1494).

OfCornelius AgrippaandJohann Weyer,author ofDe Præstigiis Demonum(Basle, 1566), whose views he adopted, he spoke with respect. Scot did adopt contemporary superstition in his references to medicine and astrology. He believed in the medicinal value of theunicorn's horn, and thought that precious stones owed their origin to the influence of the heavenly bodies. The book also narrates stories of strange phenomena in the context of religious convictions. The devil is related with such stories and his ability to absorb people's souls. The book also gives stories of magicians with supernatural powers performing in front of courts of kings.

Influence

[edit]The Discoverie of WitchcraftandThe First Part of Clever and Pleasant Inventionsby Jean Prevost, both published in 1584, are considered the seminal works of magic.[3]Scot's volume became an exhaustive encyclopædia of contemporary beliefs about witchcraft, spirits,alchemy,[4]magic, andlegerdemain,as well as attracting widespread attention to his scepticism on witchcraft.William Shakespearedrew from his study of Scot's book hints for his picture of the witches inMacbeth,andThomas Middletonin his play ofThe Witchlikewise was indebted to this source. Through bibliographies, one may trace moderngrimoiresto this work. The chapter onmagic tricksin Scot'sDiscoveriewas later plagiarised heavily; it was the basis ofThe Art of Juggling(1612) by S. R., andHocus Pocus Junior(1634).[5][6]Scot's early writings constituted a substantial portion (in some cases, nearly all) of the text in English-language stage magic books of the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the principles of conjuring and sleight of hand outlined by Scot are still used by modern magicians.[7]These include sleight of hand tricks involving balls, coins, and playing cards, and the use of confederates. The book is still highly sought after by collectors and historians of magic.[7]

Controversy

[edit]The debate over the contested Christian doctrine continued for the following decades.Gabriel Harvey,in hisPierce's Supererogation(1593),[8]wrote:

Scotte's discoovery of Witchcraft dismasketh sundry egregious impostures, and in certaine principall chapters, and speciall passages, hitteth the nayle on the head with a witnesse; howsoever I could have wished he had either dealt somewhat more curteously with Monsieur Bondine [i.e. Bodin], or confuted him somewhat more effectually.

William Perkinssought to refute Scot, and was joined by the powerfulJames VI of Scotlandin hisDæmonologie(1597), referring to the opinions of Scot as "damnable".John RainoldsinCensura Librorum Apocryphorum(1611),Richard BernardinGuide to Grand Jurymen(1627),Joseph GlanvillinPhilosophical Considerations touching Witches and Witchcraft(1666), andMeric CasauboninCredulity and Uncredulity(1668) continued the attack on Scot's position.

Scot found contemporary support in the influentialSamuel Harsnet,and his views continued to be defended later byThomas AdyCandle in the Dark: Or, A Treatise concerning the Nature of Witches and Witchcraft(1656), and byJohn WebsterinThe Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft(1677) and was known to typical lay sceptics such asHenry Oxinden.

Later editions

[edit]The book was well-received abroad. A translation into Dutch, edited by Thomas Basson, an English stationer living atLeiden,appeared there in 1609. It was undertaken on the recommendation of the professors, and was dedicated to the university curators and theburgomasterof Leiden. A second edition, published by G. Basson, the first editor's son, was printed at Leiden in 1637.

In 1651 the book was twice reissued in London inquartoby Richard Cotes; the two issues differ slightly in the imprint on the title page. Another reissue was dated 1654. A third edition in folio, dated 1665, included nine new chapters, and added a second book to "The Discourse on Devils and Spirits". The third edition was published with two imprints in 1665, one being the Turk Head edition, the scarcer variant was at the Golden-Ball. In 1886Brinsley Nicholsonedited a reprint of the first edition of 1584, with the additions of that of 1665. This edition was limited to 250 copies of which the first 50 were numbered restricted editions with a slip of paper inserted by Elliot Stock at the beginning. The binding was also different.

Notes

[edit]- ^Almond, Philip C. (2009). "King James I and the burning of Reginald Scot's The Discoverie of Witchcraft: The invention of a tradition".Notes and Queries.56(2): 209–213.doi:10.1093/notesj/gjp002.

- ^Scot, Reginald (1651).The Discoverie of Witchcraft.Richard Cotes. p. 349.

- ^"Ricky Jay: Deceptive Practice ~ Ricky Jay's Encyclopaedia Britannica Conjuring Entry | American Masters | PBS".American Masters.21 January 2015.Retrieved7 July2022.

- ^"Reginald Scot on alchemy".www.levity.com.

- ^Wootton, David. "Scot, Reginald".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24905.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^"Hocus Pocus, Jr".www.hocuspocusjr.com.

- ^abCopperfield, David;Wiseman, Richard;Britland, David (2021).David Copperfield's history of magic.New York, NY.ISBN978-1-9821-1291-2.OCLC1236259508.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ed. Grosart, ii. 291.

References

[edit]- Scot, Reginald,The Discoverie of Witchcraft,Dover Publications, Inc., New York: 1972.ISBN0-486-26030-5.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:"Scott, Reginald".Dictionary of National Biography.London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:"Scott, Reginald".Dictionary of National Biography.London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

Further reading

[edit]- Almond, Philip C. (2011).England's First Demonologist: Reginald Scot and "The Discoverie of Witchcraft".London: I.B. Tauris.ISBN9781848857933.

- Estes, Leland L.Reginald Scot and His "Discoverie of Witchcraft": Religion and Science in the Opposition to the European Witch Craze,Church History, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Dec., 1983), pp. 444–456.

- Haight, Anne Lyon (1978).Banned Books, 387 B.C. to 1978 A.D..updated and enl. by Chandler B. Grannis (4th ed.). New York: R.R. Bowker.ISBN0-8352-1078-2.

External links

[edit]- Scan of a copy of the first edition of 1584in the Boston Public Library (Internet Archive)

- Scan of a copy of the reprint of 1886with introduction and notes by Brinsley Nicholson (Internet Archive)