Doctors' Commons

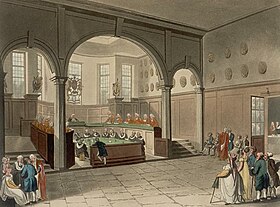

Doctors' Commons,also called theCollege of Civilians,was a society of lawyers practisingcivil (as opposed to common) lawinLondon,namely ecclesiastical and admiralty law. Like theInns of Courtof thecommon lawyers,the society had buildings with rooms where its members lived and worked, and a large library.

It was also a lower venue for determinations and hearings, short of the society's convening in theCourt of the ArchesorAdmiralty Court,which frequently consisted of judges with other responsibilities and from which further appeal lay. The society usedSt Benet's, Paul's Wharfas its church.[1]

The civil law in England[edit]

While theEnglish common law,unlike the legal systems on the European continent, developed mostly independently fromRoman law,some specialised English courts applied the Roman-based civil law. This is true of theecclesiastical courts,whose practice even after theEnglish Reformationcontinued to be based on thecanon lawof theRoman Catholic Church,and also of theadmiralty courts.Until reforms in the 19th century, the ecclesiastical courts performed functions equivalent to today'sprobate courts,subject then to appeals to separate courts (of equity), andfamily courts(however divorce was much harder to achieve).

The advocates practising in these courts had been trained in canon law (before the Reformation) and in Roman law (after) at the university colleges ofOxfordandCambridge.This profession was split, like its common law counterpart. The advocates (the doctors) were akin tobarristersin the common-law courts, while the proctors were akin toattorneysin the common-law courts or tosolicitorsin the courts of equity.

According to some accounts, the society of Doctors' Commons was formed in 1511 by Richard Blodwell,Dean of the Arches.He served nine years. According to others, it existed in the previous century. The society's buildings, acquired in 1567, were nearSt. Paul's CathedralatPaternoster Row,and remained in use for many years;[2]however, in the society's final decades nearby buildings inKnightrider Streetwere used instead.[3]

In 1768 the society was incorporated. It took official name of the "College of Doctors of Law exercent in the Ecclesiastical and Admiralty Courts". The college still consisted of its president (theDean of Arches) and of those doctors of law who, havingregularlytaken that degree in the universities of Oxford or Cambridge, and having been admitted advocates in pursuance of the rescript of thearchbishop of Canterbury,were elected "fellows" in the manner prescribed by the charter. There were also attached to the college thirty-four "proctors",whose duties were analogous to those ofsolicitors.[2]

Disestablishment[edit]

In the nineteenth century, the institution of Doctors' Commons and its members were looked upon as old-fashioned and slightly ridiculous.[4]As anticipation of an impending abolition grew, there was a reluctance among the society to admit new fellows as this would dilute the proceeds of any winding up of the property. DrThomas Hutchinson Tristramwas the last to be admitted.[5]

TheCourt of Probate Act 1857abolished thetestamentaryjurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts and gave common lawyers the right to practise in fields which before had been the exclusive domain of civilians (doctors and proctors), while offering in practice scant compensation of the reverse also being permitted.[5]Critically, the Act also made it lawful for the Doctors' Commons, by a vote of the majority of its fellows, to dissolve itself and surrender itsRoyal Charter,the proceeds of dissolution to be shared among the members.[6]

TheMatrimonial Causes Act 1857created a newdivorcecourt in which regularbarristersor doctors of Doctors' Commons couldappear.

TheHigh Court of Admiralty Act 1859liberalisedrights of audiencein theAdmiralty Court.This left to Doctors' Commons only the established church'sCourt of Arches.[5]

A motion to dissolve the society was entered on 13 January 1858 setting the path towards the last meeting which was the end ofTrinity Term,10 July 1865. The fellows, rather than surrender their offices and charter, resolved that its property was to be sold and no appointments to any vacant post could be made.[7]The buildings of Doctors' Commons were sold in 1865 and demolished soon after. The site is now largely occupied by theFaraday Building.[8]

The Court of Arches gave right of audience to barristers in 1867.[5][9]

The society perished with the death of its last fellow Tristram in 1912.

In Victorian literature[edit]

Satirical descriptions of Doctors' Commons can be found inCharles Dickens'sSketches by Bozand inDavid Copperfieldin which Dickens called it a "cosey, dosey, old-fashioned, time-forgotten, sleepy-headed little family party."[4]

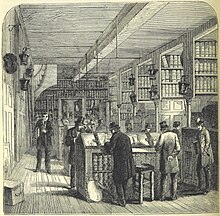

In the same-era novelThe MoonstonebyWilkie Collins,thesolicitorofGray's Inn SquareMathew Bruff notes, "I shall perhaps do well if I explain in this place, for the benefit of the few people who don't know it already, that the law allows allwillsto be examined at Doctor's Commons by anybody who applies, on payment of ashillingfee. "[10]

Doctors' Commons is mentioned anachronistically in the much later short storyThe Adventure of the Speckled BandbySir Arthur Conan Doyle,in whichSherlock Holmesapparently obtains some information there about the will of the wife of Dr Grimesby Roylott of Stoke Moran.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"St Benet Paul's Wharf".Britain Express.Retrieved1 August2015.

- ^abChisholm 1911.

- ^Baker 1998,p. 59, n. 8.

- ^abDavid Copperfield(1849), Charles Dickens, chapter 23.

- ^abcdSquibb 1977,pp. 104–105.

- ^Court of Probate Act 1857, s.117

- ^Baker 1990,p. 194.

- ^Simon Bradley (ed.), Nikolaus Pevsner,London. 1. The City of London(London: Penguin Books, 1997) p. 343.

- ^Mouncey v. Robinson(1867) 37 L. J. Ecc. 8

- ^Collins 1998,pp. 274–275, 289.

Bibliography[edit]

- Baker, J.H. (1990).An Introduction to English Legal History.London: Butterworths.ISBN0-406-53101-3.

- Baker, J.H. (1998).Monuments of Endlesse Labours: English Canonists and Their Work 1300-1900.London: Hambledon Press.ISBN1-85285-167-8.

- Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Doctors' Commons".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 367.

- Collins, Wilkie (1998) [1868]. Kemp, Sandra (ed.).The Moonstone.London: Penguin Books.ISBN9780140434088.

- Outhwaite, R.B.; Helmholz, R. H. (2007).The Rise and Fall of the English Ecclesiastical Courts, 1500-1860((Cambridge Studies in English Legal History) ed.). London: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-86938-6.

- Squibb, G. D. (1977).Doctors' Commons.Oxford: University Press.ISBN0-19-825339-7.