Donkeys in Tunisia

This article has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

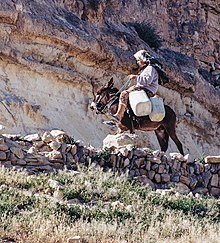

Woman carrying water containers on the back of a donkey in the Tunisian mountains | |

| Use | Working animal |

|---|---|

| |

Thedonkey in Tunisiais historically a working animal which has existed inCarthagesince theAntiquity,and had by the end of the 19th century become widespread. It was used for a number of domestic tasks, linked to traveling, and for transportation of water,agriculture,more specifically, to thecultivationandpressingofolives.The introduction of motorised vehicles considerably reduced their numbers, as their population fell by over half between 1996 and 2006, with a population of 123,000 recorded in 2006. In rural regions, the donkey is only put to use for small, specialized agricultural tasks, such as oliveharvesting.The consumption of donkey meat has always been controversial, and it is consideredmakruhto consume domesticated donkey meat in Islamic tradition. l'Association pour la culture et les arts méditerranéens (ACAM) claimed in 2010 that the donkey is under threat of extinction in Tunisia.

The donkey is culturally devalued, with its name often used as an insult in Tunisian Arabic. However, it has also been the inspiration for some literary works, such as "Dispute de l'âne" by Anselm Turmeda (1417), as well as a number offolk tales.

History

[edit]Prehistory & Antiquity

[edit]The donkey (Equus asinus) has always been a part of the rural countryside ofNorth Africa.[1]However, the origin of domesticated donkeys in the Maghreb is disputed. According to one theory, supported notably byl'Encyclopédie berbère,the domestic species is not native to the region, and is descended from theAfrican wild donkey(E. africanus), whose origins are found inEast Africa.[1]According to the theory ofColin Groves(1986), a sub-species of the North African wild donkey (Equus africanus atlanticus) had lived until the first few centuries AD, but it is not known if it was domesticated, and it seems very unlikely.,.[2][3]There are no archaeological remains of this subspecies so it can only be depicted through representations.[4]Originating in theAtlas Mountains,E. a. atlanticuswent extinct around 300 AD.[3]Whatever its exact origins, the donkey was domesticated in Africa,[5]the oldest proof of its use going back to the culture of Maadi-Bouto, inEgypt,in the 4th Millennium B.C...[6]The history of the donkey in Africa is notoriously difficult to study as, although the species was widely used, very little was written about it, no plans for the development nor for the improvement of the species were developed, and very few archaeological remnants are left.[5]There are no remains to document its existence in the Tunisian Sahara.[7]The first domesticated donkeys, who originate fromaridorsemi-aridregions, are very sensitive to humidity.[5]

Donkeys have been represented incave paintingsin areas of the Sahara since the earliest period of Antiquity,[1]notably inLibyaandMorocco.[8]InDe agri cultura,the Roman senatorCato the Eldergave a description of the donkey's role in the Mediterranean area under theRoman Empire,and in particular inCarthage.For every sixty hectares of olive groves four donkeys were needed, three to bringmanureto the soil, and one to power theoil mill.For every 25 hectares of vineyard two donkeys were needed fortillage[9].The Golden AssbyApuleiusalso provided valuable information concerning the uses of the donkey during the Antiquity in North Africa, notably regarding their use for carryingwoodand food products to sell on the market.[2]It is likely thatequine veterinarianspecialists were in work in Carthage starting from the 4th century BC.[2]Donkey remains have been found in Carthage which dates back to between the first and fourth century,[10]which are among the oldest archaeological proofs of the existence of donkeys in the Maghreb.[6]

Middle Ages

[edit]The eruditeZenataBerberAbu Yazid(873-947), who fought the Fatimides[11]and had a well-organized administration,[12]was known as "The Man on the Donkey".[13]The consumption of donkey meat would have, in all likelihood, been prohibited in Islam, to the extent thatMuslims,as well aspractising Christians in Tunisia,probably ate very little of it.[14]Ibn Battûta(1304-1377), who comes from what is now known asMorocco,noted his disgust at the fact that donkey meat was consumed in theMali Empire.[14]However, at the start of the 16th century, donkey meat was likely to have been eaten by thenomadicBerbers ofMauritania.[14]

19th Century

[edit]

According to an 1887 description provided by the naturalistJean-Marie de Lanessan,there were a very large number of donkeys:

The most common animal is, without a doubt, the donkey. There isn't a single family, no matter how poor they might be, who doesn't own a donkey. I don't think it is an overestimation to suggest there are 5 donkeys for every person, making the total number of donkeys around three hundred thousand. The animal is very small in size, yet robust, and more temperate than thecamel,if such a thing is possible. This is the animal who takes ondomestic tasks,it is the animal the women use to fetch water from thewell,and the one the men use to carry food from the markets, it is the donkey who carries everything produced in gardens and fields from the villages,corn,lucernefor thesheepandbullocksand freshly harvestedwheatandbarley.It is also the task of the donkey to transport the limited possessions of households who emigrate. The donkey is, in effect, thechargerof the poor.

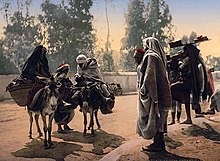

The population of the donkey in Tunisia reached its peak at the end of the 19th century, with various colonial sources reporting a population of 800,000. The animal could be spotted in particular in the mountainous regions of the north-west, the centre and the south of the country, where the ground is lessfertile.

20th & 21st Centuries

[edit]

TheFrench protectoratewas interested inrearingmulesto supply to the army and sendingFrench breedsofjacks,notablyPyrenean,Catalanand Savoyard breeds[15]to stations in various breeding centres. Controlled reproduction attempts were undertaken inSidi Thabet,where, starting from 1938, Catalan jennies were imported. This marked the start of the development of donkey breeding.[15]The Catalan donkey is known to be able to easily adapt to the Tunisian climate, in contrast with theBaudet du Poitou.[16]LaStatistique générale de la Tunisie,written by Ernest Fallot in 1931, counted 168,794 donkeys belonging to Tunisians compared to 2,388 belonging to the French.[17]

The donkey population then suffered a long decline as it was considered a relic of the past. However, the donkey population saw a large increase between 1966 and 1996, growing from an estimated 163 000 to around 230 000.[18]

In the 1990s, the remote locations of some schools and a lack ofpublic transportmade the usage of donkeys, either for pulling carriages or for carrying pupils on their backs, an indispensable tool for ensuringschool attendance.[19]Donkey breeding also saw a significant comeback for the purpose of transportingcontraband.In small Tunisian family farms, such as the famous example of Sidi Abid (2002), families preferred to purchase a donkey rather than a mule or ahorsebecause the donkey is guaranteed to help with peasant work.[20]However, the rural species has undergone noticeable changes since the 1990s as the transition fromnomadismtosedentismled to the gradual disappearance of donkeys and mules as they were replaced by motorised vehicles. Sightings of this animal are now rare.[21]In addition to this, anepizooticofequine influenzahit the country in 1998, particularly in theTozeurregion, starting from the end of the month of January, whose spread affected horses, mules and donkeys equally.[22]

Uses and practices

[edit]The donkey still plays a major role in domains such as transport for minor agricultural work, as well as in ground work.[23]Known for their temperance and hardiness, donkeys are used by the poorestTunisiansto travel or to carry water with apack saddle,abardaor azembil..[15]They may be a necessity in subdesert regions andsteppesin order to access water.Well-drillingzones can be up to several kilometres away from inhabited areas andtransporting wateris achieved either by atankwagonmade fromtinplatesupported by two wheels, or viaamphoraurns (or more recently, via plastic water containers) which are filled up and brought back by women on the backs of donkeys.[24]The donkey is used less and less frequently in rural areas, reserved only for tasks such asgatheringolives, withcarsbeing used for day-to-day transport.[21]

InToujane,the traditionaloil millwas previously run with the use of donkeys or with smalldromedarieswhich were able to set in motion a stone base weighing approximately 150 kg.[25]

The roads in the Tunisian Great South (2004) can vary dramatically and all types of vehicles run along them, such asbicycles,Mobylettes,cars,share taxisand donkey wagons. According to a source from 1979, the nomads of the Tunisian Great South had nicknamed the donkey "dàb er-rezg'' meaning" providentialworkhorse".They used the animal to pull theardin theghaba(gardens), to carry water or wood, and to accompany people duringtranshumanceand whensowingseeds.[26]As of 2011, it was still possible to see older women travel on the back of a donkey in the village of Tamezret. As of 2016, there were still a number of donkey wagons on the islands ofKerkennah.[25]

Mules were traditionally kept for the same tasks as those of donkeys.[27]

As of 2014, L'École supérieure des industries alimentaires de Tunis has been looking to promote the production and consumption ofdonkey milk,but its need to berefrigeratedin order to preserve it poses a major problem.[28]

Meat

[edit]Consumption of donkey meat is controversial; the majority of Tunisians claim to never eat it, but the rising prices ofred meat(particularly in 2012 and 2013) could have encouraged a large number of people to consume it,[29]especially in the month ofRamadan,which sees a sharp rise in the price of meat.[30][31]According to comments made in 2017 by Mohamed Rabhi, the director for the protection of health in the Tunisian Ministry for Public Health, the sale of donkey meat in Tunisia is perfectly legal.[32]According to official figures, the two Tunisianabattoirsauthorised for equine animals produced 2000 tonnes of donkey meat in 2012. However, the actual number of donkeys killed per year is believed to be around 30,000, most often to be sold fraudulently, mainly to producemerguezorshawarma:due to the infrequency of checks, it is impossible to find out exactly where this fraudulent meat is sold.[33]According toLe Muslim Post,horse meatis consideredhalal,whereas donkey meat isharam.[34]Despite this, donkey meat is said to be consumed in theslumsaround Tunis.

Culture

[edit]TheTunisian Arabicword for donkey isbhim.[35]The donkey holds very negative cultural connotations, its name serving as the equivalent to an animal epithet to call someone stupid or indecisive.[36]As such, the group Takriz, founded in 1998 with the objective of "fighting tyranny andInternet censorship in Tunisia",[37]is frequently insulted by Tunisian internet users who refer to them asbhéyém(donkeys) orchâab bhim(stupid people).[38]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcCamps, Chaker & Musso 1988.

- ^abcMitchell 2018,p. 110, 122, 126, 142, 152.

- ^abBlench 2006,p. 340.

- ^Blench 2006,p. 341.

- ^abcBlench 2006,p. 339.

- ^abBlench 2006,p. 344.

- ^Mitchell 2018,p. 68.

- ^Blench 2006,p. 345.

- ^Mitchell 2018,chap. The Agricultural Donkey.

- ^Baroin, Catherine; Boutrais, Jean (1999).L'homme et l'animal dans le bassin du lac Tchad(in French). Paris: Institut de recherche pour le développement. p. 705.ISBN2709914360.OCLC43730295..

- ^Ibn Khaldoun(2003).Histoire des Berbères(in French). Alger: Berti. pp. 849–852..

- ^Arthur Pellegrin(1944).Histoire de la Tunisie(in French). Tunis: Imprimerie La Rapide. p. 101..

- ^Djaffar Mohamed-Sahnoun (2006).Les chi'ites(in French). Paris: Publibook. p. 322.ISBN2748308379.OCLC77078255..

- ^abcBlench 2006,p. 343.

- ^abcDenjean 1950,p. 25.

- ^Denjean 1950,p. 26.

- ^Ernest Fallot (1931).Statistique générale de la Tunisie(in French). Tunis: Société anonyme de l'imprimerie rapide. p. 261..

- ^Starkey & Starkey 2000,p. 14.

- ^Mongi Bousnina(1991).Développement scolaire et disparités régionales en Tunisie(in French). Tunis: Université de Tunis. p. 269.ISBN9973922069.OCLC28180746..

- ^Laroussi Amri (2002).La femme rurale dans l'exploitation familiale, Nord-Ouest de la Tunisie(in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 116–538.ISBN2747549100.OCLC54047036..

- ^abMohsen Kalboussi (2 May 2019)."Quels horizons pour l'espace rural en Tunisie?".nawaat.org(in French).Retrieved5 June2019..

- ^"À propos d'une épizootie de grippe équine".Archives de l'Institut Pasteur de Tunis(in French). 77 et 78: 69–72. 2000.ISSN0020-2509..

- ^Elati et al. 2018,p. 1.

- ^Hubert 1984,p. 103.

- ^abDominique Auzias; Jean-Paul Labourdette (2016). "Toujane / Îles Kerkennah".Djerba 2016.Carnets de voyages (in French). Paris:Petit Futé.p. 144.ISBN9791033100300..

- ^André Louis (1979).Nomades d'hier et d'aujourd'hui dans le Sud tunisien(in French). Aix-en-Provence:Édisud.p. 30 and 56.ISBN2857440367.OCLC5889083..

- ^Denjean 1950,p. 27.

- ^"Developping [sic] Donkey Milk from Circummediterranean Race and Storing Tests at the Sidi Mreyeh Region (Zaghouan) "(PDF).lactimed.eu.5 May 2014. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 11 September 2016.Retrieved4 June2019..

- ^Amel Zaibi (4 May 2013)."Tunisie: commercialisation de la viande d'âne - La transparence fait défaut".fr.allafrica.com(in French).Retrieved31 May2019..

- ^"Tunisie: de la viande d'âne pour Ramadan!".investir-en-tunisie.net(in French). 3 August 2012.Retrieved7 June2019..

- ^"Tunisie: augmentation de la demande sur la viande d'âne au marché central".tuniscope.com(in French). 3 August 2012.Retrieved7 June2019..

- ^"La vente de viande d'âne est légale!".realites.com.tn(in French). 9 September 2017.Retrieved7 June2019..

- ^"30 000 ânes égorgés chaque année pour" confectionner "des merguez".realites.com.tn(in French). 16 October 2017.Retrieved7 June2019..

- ^Yassine Bannani (20 April 2015)."Halal en Tunisie: de l'âne au lieu du cheval".lemuslimpost.com(in French).Retrieved31 May2019..

- ^Édouard Gasselin (1869).Petit guide de l'étranger à Tunis(in French). Paris: Chez Challamel. p. 63..

- ^"Les ânes en Tunisie ont maintenant une association".tuniscope.com(in French). 13 September 2010.Retrieved31 May2019..

- ^"Takriz - À propos".fr-ca.facebook.com(in French).Retrieved7 July2019..

- ^Sihem Najar (2013).Les réseaux sociaux sur Internet à l'heure des transitions démocratiques(in French). Paris: Karthala. pp. 323–489.ISBN9782811109769.OCLC858232295..

Bibliography

[edit]- Blench, Roger M. (2006). "A history of donkeys, wild asses and mules in Africa".The Origins and Development of African Livestock: Archaeology, Genetics, Linguistics and Ethnography.Londres: Routledge. pp. 339–354.ISBN9781135434168.

- Camps, Gabriel;Chaker, Salem;Musso, Jean-Claude (1988). "Âne".Encyclopédie berbère(in French). Aix-en-Provence: Édisud. pp. 647–657.ISBN978-2-857-44319-3.

- Denjean, Y. (1950)."L'élevage des ânes et des mulets en Tunisie"(PDF).Bulletin économique et social de la Tunisie(in French).47:25–38.Retrieved5 June2019..

- Elati, Khawla; Chiha, Hounaida; Khamassi Khbou, Médiha; Gharbi, Mohamed (2018)."Activity Dynamics ofGasterophilus spp.Infesting Donkeys (Equus asinus) in Tunisia "(PDF).The Journal of Advances in Parasitology.5(1): 1–5.doi:10.17582/journal.jap/2018/5.1.1.5(inactive 2024-04-11).ISSN2311-4096.Retrieved4 June2019.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - Hubert, Annie (1984).Le Pain et l'olive' - aspects de l'alimentation en Tunisie(in French). Paris: Éditions du CNRS.ISBN2222034426.

- Mitchell, Peter (2018).The Donkey in Human History - An Archaeological Perspective.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN9780192538123.

- Starkey, Paul; Starkey, Malcolm (2000). "Regional and world trends in donkey populations".Donkeys, people and development.Wageningue: Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa. pp. 10–21.CiteSeerX10.1.1.403.4880.ISBN92-9081-219-2.