Dutch people

Nederlanders | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 30–35 million[a] Dutch diaspora and ancestry:c. 14 million  | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Netherlands16,366,000[1] (Self-identified ethnic Dutch and those legally treated as Dutch, e.g.MoluccansperFaciliteitenwet)[1] | |

| United States[b] | 3,083,000[2] |

| South Africa[b][d] | 3,000,000[3][4] |

| Canada[b] | 1,112,000[5] |

| Australia[b] | 336,000[6] |

| Germany | 257,000[7] |

| Belgium[b] | 121,000[8] |

| New Zealand[b] | 100,000[9] |

| France | 60,000[10] |

| United Kingdom | 56,000[11] |

| Spain | 48,000[12] |

| Denmark | 30,000[13] |

| Switzerland | 20,000[14] |

| Indonesia | 17,000[13] |

| Turkey | 15,000[15] |

| Norway | 13,000[16] |

| Italy | 13,000[12] |

| Portugal | 12,000[17] |

| Curaçao | 10,000[12] |

| Sweden | 10,000[13] |

| Israel | 5,000[12] |

| Aruba | 5,000[12] |

| Luxembourg | 5,000[12] |

| Hungary | 4,000[12] |

| Austria | 3,200[12] |

| Poland | 3,000[12] |

| Suriname | 3,000[12] |

| Japan | 1,000[12] |

| Greece | 1,000[12] |

| Thailand | 1,000[12] |

| Languages | |

| PrimarilyDutch andother regional languages: Dutch Low Saxon[a] Limburgish[b][18] West Frisian(Friesland)[c][19][20] English(BES Islands)[d][21] Papiamento(Bonaire)[e][21][22] | |

| Religion | |

| Majorityirreligious[23][24] Historically or traditionallyChristian (Roman CatholicandProtestant)[c][25] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| |

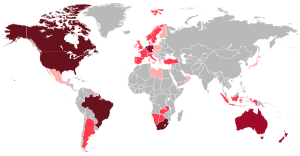

TheDutch(Dutch:) are anethnic groupnative to theNetherlands.They share a common ancestry and culture and speak theDutch language.Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably inAruba,Suriname,Guyana,Curaçao,Argentina,Brazil,Canada,[26]Australia,[27]South Africa,[28]New Zealandand theUnited States.[29]TheLow Countrieswere situated around the border ofFranceand theHoly Roman Empire,forming a part of their respective peripheries and the various territories of which they consisted had become virtually autonomous by the 13th century.[30]Under theHabsburgs,the Netherlands were organised into a single administrative unit, and in the 16th and 17th centuries the Northern Netherlands gained independence fromSpainas theDutch Republic.[31]The high degree ofurbanisationcharacteristic of Dutch society was attained at a relatively early date.[32]During the Republic the first series of large-scale Dutch migrations outside ofEuropetook place.

The traditional arts and culture of the Dutch encompasses various forms oftraditional music,dances,architectural stylesand clothing, some of which are globally recognisable. Internationally, Dutch painters such asRembrandt,VermeerandVan Goghare held in high regard. The predominant religion among the Dutch isChristianity,encompassing bothCatholicismandProtestantism.However, in contemporary times, the majority no longer adhere to a particular Christian denomination. Significant percentages of the Dutch are adherents ofhumanism,agnosticism,atheismorindividual spirituality.[33][34][35]

History

[edit]Emergence

[edit]As with all ethnic groups, theethnogenesisof the Dutch (and their predecessors) has been a lengthy and complex process. Though the majority of the defining characteristics (such as language, religion, architecture or cuisine) of the Dutch ethnic group have accumulated over the ages, it is difficult (if not impossible) to clearly pinpoint the exact emergence of the Dutch people.

General

[edit]In the first centuries CE, the Germanic tribes formed tribal societies with no apparent form ofautocracy(chiefs only being elected in times of war), had religious beliefs based onGermanic paganismand spoke a dialect still closely resemblingCommon Germanic.Following the end of the migration period in the West around 500, with large federations (such as theFranks,Vandals,AlamanniandSaxons) settling the decayingRoman Empire,a series of monumental changes took place within these Germanic societies. Among the most important of these are theirconversionfrom Germanic paganism toChristianity,the emergence of a new political system, centered on kings, and a continuing process of emerging mutual unintelligibility of their various dialects.

Specific

[edit]

The general situation described above is applicable to most if not all modern European ethnic groups with origins among theGermanic tribes,such as the Frisians, Germans, English and the Nordic (Scandinavian) peoples. In the Low Countries, this phase began when theFranks,themselves a union of multiple smaller tribes (many of them, such as theBatavi,Chauci,ChamaviandChattuarii,were already living in the Low Countries prior to the forming of the Frankish confederation), began to incur the northwestern provinces of theRoman Empire.Eventually, in 358, theSalian Franks,one of the three main subdivisions among the Frankish alliance,[37]settled the area's Southern lands asfoederati;Roman allies in charge of border defense.[38]

LinguisticallyOld Frankishgradually evolved intoOld Dutch,[40][41]which was first attested in the 6th century,[42]whereas religiously the Franks (beginning with theupper class) converted toChristianityfrom around 500 to 700. On a political level, the Frankish warlords abandoned tribalism[43]and founded a number of kingdoms, eventually culminating in theFrankish EmpireofCharlemagne.

However, the population make-up of the Frankish Empire, or even early Frankish kingdoms such asNeustriaandAustrasia,was not dominated by Franks. Though the Frankish leaders controlled most of Western Europe, the Franks themselves were confined to the Northwestern part (i.e. theRhineland,the Low Countries and NorthernFrance) of the Empire.[44]Eventually, the Franks in Northern France were assimilated by the generalGallo-Romanpopulation, and took over their dialects (which becameFrench), whereas the Franks in the Low Countries retained their language, which would evolve into Dutch. The current Dutch-French language border has (with the exception of theNord-Pas-de-Calaisin France andBrusselsand the surrounding municipalities in Belgium) remained virtually identical ever since, and could be seen as marking the furthest pale ofgallicisationamong the Franks.[45]Adialect continuumremaining with more eastern Germanic populations, a distinct identity in relation to these only gradually developed, largely based on socio-economic and political factors. Large parts of the present Netherlands have populations using Saxon and Frisian dialects.

Convergence

[edit]The medieval cities of the Low Countries, especially those of Flanders, Brabant and Holland, which experienced major growth during the 11th and 12th centuries, were instrumental in breaking down the already relatively loose local form of feudalism. As they became increasingly powerful, they used their economic strength to influence the politics of their nobility.[46][47][48]During the early 14th century, beginning in and inspired by the County of Flanders,[49]the cities in the Low Countries gained huge autonomy and generally dominated or greatly influenced the various political affairs of the fief, including marriage succession.

While the cities were of great political importance, they also formed catalysts for medieval Dutch culture. Trade flourished, population numbers increased dramatically, and (advanced) education was no longer limited to the clergy. Flanders, Brabant and Holland began to develop a common Dutchstandard language.Dutch epic literature such asElegast(1150), theRoelantsliedandVan den vos Reynaerde(1200) were widely enjoyed. The various city guilds as well as the necessity ofwater boards(in charge of dikes, canals, etc.) in the Dutch delta and coastal regions resulted in an exceptionally high degree of communal organisation. It is also around this time, that ethnonyms such asDietsandNederlandsemerge.[50]

In the second half of the 14th century, the dukes of Burgundy gained a foothold in the Low Countries through the marriage in 1369 ofPhilip the Boldof Burgundy to the heiress of the Count of Flanders. This was followed by a series of marriages, wars, and inheritances among the other Dutch fiefs and around 1450 the most important fiefs were under Burgundian rule, while complete control was achieved after the end of theGuelders Warsin 1543, thereby unifying the fiefs of the Low Countries under one ruler. This process marked a new episode in the development of the Dutch ethnic group, as now political unity started to emerge, consolidating the strengthened cultural and linguistic unity.

Consolidation

[edit]

Despite their growing linguistic and cultural unity, and (in the case ofFlanders,BrabantandHolland) economic similarities, there was still little sense of political unity among the Dutch people.[51]

However, the centralist policies of Burgundy in the 14th and 15th centuries, at first violently opposed by the cities of the Low Countries, had a profound impact and changed this. DuringCharles the Bold's many wars, which were a major economic burden for the Burgundian Netherlands, tensions slowly increased. In 1477, the year of Charles' suddendeath at Nancy,the Low Countries rebelled against their new liege,Mary of Burgundy,and presented her with a set of demands.

The subsequently issuedGreat Privilegemet many of these demands, which included that Dutch, not French, should be the administrative language in the Dutch-speaking provinces under Burgundian rule (i.e. Flanders, Brabant and Holland) and that theStates-Generalhad the right to hold meetings without the monarch's permission or presence. The overall tenor of the document (which was declared void by Mary's son and successor,Philip IV) aimed for more autonomy for the counties and duchies, but nevertheless all the fiefs presented their demands together, rather than separately. This is evidence that by this time a sense of common interest was emerging among the provinces of the Netherlands. The document itself clearly distinguishes between the Dutch speaking and French speaking provinces.

Following Mary's marriage toMaximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor,the Netherlands were now part of the Habsburg lands. Further centralised policies of the Habsburgs (like their Burgundian predecessors) again met with resistance, but, peaking with the formation of the collateral councils of 1531 and thePragmatic Sanction of 1549creating theSeventeen Provinces,were still implemented. The rule ofPhilip II of Spainsought even further centralist reforms, which, accompanied by religious dictates and excessive taxation, resulted in theDutch Revolt.The Dutch provinces, though fighting alone now, for the first time in their history found themselves fighting a common enemy. This, together with the growing number of Dutch intelligentsia and theDutch Golden Agein whichDutch culture,as a whole, gained international prestige, consolidated the Dutch as an ethnic group.

National identity

[edit]

By the middle of the 16th century an overarching, 'national' (rather than 'ethnic') identity seemed in development in the Habsburg Netherlands, when inhabitants began to refer to it as their 'fatherland' and were beginning to be seen as a collective entity abroad; however, the persistence of language barriers, traditional strife between towns, and provincial particularism continued to form an impediment to more thorough unification.[52]Following excessivetaxationtogether with attempts at diminishing the traditional autonomy of the cities and estates in the Low Countries, followed by the religious oppression after being transferred toHabsburg Spain,the Dutch revolted, in what would become theEighty Years' War.For the first time in their history, the Dutch established their independence from foreign rule.[53]However, during the war it became apparent that the goal of liberating all the provinces and cities that had signed theUnion of Utrecht,which roughly corresponded to the Dutch-speaking part of the Spanish Netherlands, was unreachable. The Northern provinces were free, but during the 1580s the South was recaptured by Spain, and, despite various attempts, the armies of the Republic were unable to expel them. In 1648, thePeace of Münster,ending theEighty Years' War,acknowledged the independence of theDutch Republic,but maintained Spanish control of theSouthern Netherlands.Apart from a brief reunification from 1815 until 1830, within theUnited Kingdom of the Netherlands(which included theFrancophones/Walloons) the Dutch have been separated from the "Flemings" to this day. The border between the Netherlands and Belgium is purely contingent, simply reflecting the 1648 cease-fire line. There is a perfect dialect continuum.

Dutch Empire

[edit]The Dutch colonial empire (Dutch:Het Nederlandse Koloniale Rijk) comprised the overseas territories and trading posts controlled and administered by Dutch chartered companies (mainly theDutch West India Companyand theDutch United East India Company) and subsequently by the Dutch Republic (1581–1795), and by the modern Kingdom of the Netherlands after 1815.

Ethnic identity

[edit]

Hollander vs. Nederlander

[edit]Many Dutch people (Nederlanders) will object to being calledHollandersas a national denominator on much the same grounds as manyWelshorScotswould object to being calledEnglishinstead ofBritish,[54]as theHollandregion only comprises two of the twelve provinces, and 40% of the Dutch citizens. The same holds for the country being referred to asHollandinstead ofThe Netherlands.In January 2020, the Dutch government officially dropped its support of the wordHollandfor the whole country.[55][56]

(Multi)cultural identity

[edit]The ideologies associated with(Romantic) Nationalismof the 19th and 20th centuries never really caught on in the Netherlands.[citation needed]The (re)definition of Dutch cultural identity has become a subject of public debate following the increasing influence of theEuropean Unionand the influx of non-Western immigrants in the post-World War IIperiod. In this debate typically Dutch traditions have been put to the foreground.[57]

In sociological studies and governmental reports, ethnicity is often referred to with the termsautochtoonandallochtoon.[58]These legal concepts refer to place of birth and citizenship rather than cultural background and do not coincide with the more fluid concepts of ethnicity used by cultural anthropologists.

Greater Netherlands

[edit]As did many European ethnicities during the 19th century,[59]the Dutch also saw the emerging of variousGreater Netherlands- andpan-movements seeking to unite the Dutch-speaking peoples across the continent, while trying to counteractPan-Germanictendencies. During the first half of the 20th century, there was a prolific surge in writings concerning the subject. One of its most active proponents was the historianPieter Geyl,who wroteDe Geschiedenis van de Nederlandsche stam('The History of the Dutch tribe/people') as well as numerous essays on the subject.

During World War II, when both Belgium and the Netherlands fell toGerman occupation,fascist elements (such as theNSBandVerdinaso) tried to convince theNazisinto combining the Netherlands andFlanders.The Germans however refused to do so, as this conflicted with their ultimate goal, theNeuordnung('New Order') of creating a single pan-Germanic racial state.[60]During the entire Nazi occupation, the Germans denied any assistance to Greater Dutchethnic nationalism,and, by decree ofHitlerhimself, actively opposed it.[61]

The 1970s marked the beginning of formal cultural and linguistic cooperation between Belgium (Flanders) and the Netherlands on an international scale.

Statistics

[edit]The total number of Dutch can be defined in roughly two ways. By taking the total of all people with full Dutch ancestry, according to the current CBS definition (both parents born in the Netherlands), resulting in an estimated 16,000,000 Dutch people,[note 1]or by the sum of all people worldwide with both full and partialDutch ancestry,which would result in a number around 33,000,000.

Approximate distribution of native Dutch speakers worldwide. Netherlands (70.8%) Belgium (27.1%) Suriname (1.7%) Caribbean (0.1%) Other (0.3%)

|

Linguistics

[edit]Language

[edit]Dutch is the main language spoken by most Dutch people. It is aWest Germanic languagespoken by around 29 million people. Old Frankish, a precursor of the Dutch standard language, was first attested around 500,[62]in a Frankish legal text, theLex salica,and has a written record of more than 1500 years, although the material before around 1200 is fragmentary and discontinuous.

As a West Germanic language, Dutch is related to other languages in that group such asWest Frisian,EnglishandGerman.Many West Germanic dialects underwent a series of sound shifts. TheAnglo-Frisian nasal spirant lawandAnglo-Frisian brighteningresulted in certain early Germanic languages evolving into what are now English and West Frisian, while theSecond Germanic sound shiftresulted in what would become (High) German. Dutch underwent none of these sound changes and thus occupies a central position in theWest Germanic languagesgroup.

Standard Dutch has a sound inventory of thirteen vowels, sixdiphthongsand twenty-three consonants, of which thevoiceless velar fricative(hard ch) is considered a well known sound, perceived as typical for the language. Other relatively well known features of the Dutch language and usage are the frequent use of digraphs likeOo,Ee,UuandAa,the ability to formlong compoundsand the use of slang, includingprofanity.

The Dutch language has many dialects. These dialects are usually grouped into six main categories;Hollandic,West-Flemish/Zeelandic,East Flemish,BrabanticandLimburgish.The Dutch part ofLow Saxonis sometimes also viewed as a dialect of Dutch as it falls in the area of the Dutch standard language.[63]Of these dialects, Hollandic and Dutch Low Saxon are solely spoken by Northerners. Brabantic, East Flemish,West-Flemish/Zeelandicand Limburgish are cross border dialects in this respect. Lastly, the dialectal situation is characterised by the major distinction between'Hard G' and 'Soft G' speaking areas(see alsoDutch phonology). Some linguists subdivide these into approximately 28 distinct dialects.[64]

Dutch immigrants also exported the Dutch language. Dutch was spoken by some settlers in the United States as a native language from the arrival of the first permanent Dutch settlers in 1615, surviving in isolated ethnic pockets until about 1900, when it ceased to be spoken except by first generation Dutch immigrants. The Dutch language nevertheless had a significant impact on the region aroundNew York.For example, the first language ofU.S. presidentMartin Van Burenwas Dutch.[65][66]Most of the Dutch immigrants of the 20th century quickly began to speak the language of their new country. For example, of the inhabitants of New Zealand, 0.7% say their home language is Dutch,[67]despite the percentage of Dutch heritage being considerably higher.[68]

Dutch is currently anofficial languageof theKingdom of the Netherlands(Netherlands,Aruba,Sint Maarten,andCuraçao), Belgium,Suriname,theEuropean Union,and theUnion of South American Nations(due to Suriname being a member). InSouth AfricaandNamibia,Afrikaansis spoken, a daughter language of Dutch, which itself was an official language of South Africa until 1983. The Dutch, Flemish and Surinamese governments coordinate their language activities in theNederlandse Taalunie('Dutch Language Union'), an institution also responsible for governing the Dutch Standard language, for example in matters oforthography.

Etymology of autonym and exonym

[edit]The origins of the wordDutchgo back to Proto-Germanic, the ancestor of all Germanic languages,*theudo(meaning "national/popular" ); akin to Old Dutchdietsc,Old High Germandiutsch,Old EnglishþeodiscandGothicþiudaall meaning "(of) the common (Germanic) people ". As the tribes among the Germanic peoples began to differentiate its meaning began to change. TheAnglo-SaxonsofEnglandfor example gradually stopped referring to themselves asþeodiscand instead started to useEnglisc,after their tribe. On the continent*theudoevolved into two meanings:DietsorDuutsmeaning "Dutch (people)" (archaic)[69]andDeutsch(German,meaning "German (people)" ). At first the English language used (the contemporary form of)Dutchto refer to any or all of the Germanic speakers on the European mainland (e.g. the Dutch, the Frisians and the Germans). Gradually itsmeaning shiftedto the Germanic people they had most contact with, both because of their geographical proximity, but also because of the rivalry in trade and overseas territories: the people from the Republic of the Netherlands, the Dutch.

In theDutch language,the Dutch refer to themselves asNederlanders.Nederlandersderives from the Dutch wordNeder,a cognate ofEnglishNetherboth meaning "low",and"near the sea"(same meaning in both English and Dutch), a reference to the geographical texture of the Dutch homeland; the western portion of theNorth European Plain.[70][71][72][73][excessive citations]Although not as old asDiets,the termNederlandshas been in continuous use since 1250.[50]

Names

[edit]Tussenvoegsels

[edit]Dutch surnames (and surnames of Dutch origin) are generally easily recognisable. Many Dutch surnames feature atussenvoegsel(lit. 'between-joiner'), which is afamily name affixpositioned between a person'sgiven nameand the main part of theirfamily name.[74]The most commontussenvoegselsarevan(e.g. A.van Gogh"from/of" ),de / der / den / te / ter / ten(e.g. A.de Vries,"the" ),het / ’t(e.g. A.’t Hart,"the" ), andvan de / van der / van den(e.g. A.van den Berg,"from/of the" ). These affixes are not merged, nor capitalised by default. The second affix in a Dutch surname is never capitalised (e.g.Vanden Berg). The first affix in a Dutch surname is only capitalised if it is not preceded by a first name, initial or other surname.[75][76]For exampleVincentvan Gogh,V.van Gogh, mr.Van Gogh,Van GoghandV.van Gogh-vanden Bergare all correct, butVincentVan Goghis wrong. Many surnames ofDutch diaspora(mainly in theEnglish-speaking worldandFrancophonie) are adapted, not only in pronunciation but also in spelling. For example, by merging and capitalising the affixes and main parts of the surnames (e.g.A.van der BiltbecomesA.Vanderbilt).

Spelling

[edit]Dutch names can differ greatly in spelling. The surnameBaks,for example is also recorded asBacks,Bacxs,Bax,Bakx,Baxs,Bacx,Backx,BakxsandBaxcs.Though written differently, pronunciation remains identical. Dialectal variety also commonly occurs, withDe SmetandDe Smitboth meaningSmithfor example.

Main types of surnames

[edit]There are several main types of surnames in Dutch:

- Patronymic surnames;the name is based on the personal name of the father of the bearer. Historically this has been by far the most dominant form. These type of names fluctuated in form as the surname was not constant. If a man calledWillem Janssen(William, John's son) had a son named Jacob, he would be known asJacob Willemsen(Jacob, Williams' son). Following civil registry, the form at time of registry became permanent. Hence today many Dutch people are named after ancestors living in the early 19th century when civil registry was introduced to theLow Countries.These names rarely featuretussenvoegsels.Similar to English names like Johnson.

- Toponymic surnames;the name is based on the location on which the bearer lives or lived. In Dutch this form of surname nearly always includes one or severaltussenvoegsels,mainlyvan,van deand variants wherevanis translated asfrom.Many emigrants removed the spacing and capitalised these words, leading to derived names for well-known people likeCornelius Vanderbilt.[77]Vantranslated asof(Dutch language does not distinguish between "of" and "from" both indicated by "van" ), Dutch surnames can sometimes refer toupper classor aristocratic titles (e.g.William, Prince of Orange). However, in Dutchvanmostly reflects the place of origin of the family and not any aristocratic claim to a holding (Van der Bilt– one who comes fromDe Bilt).[78]

- Occupational surnames;the name is based on the occupation of the bearer. Well known examples includeMolenaar,VisserandSmit.This practice is similar to English surnames (the example names translate perfectly toMiller,FisherandSmith).[79]

- Cognominal surnames;based on nicknames relating tophysical appearanceor otherfeatures,on the appearance or character of the bearer (at least at the time of registration). For exampleDe Lange('the tall one'),De Groot('the big one'),De Dappere('the brave').

- Other surnames may relate to animals. For example;De Leeuw('The Lion'),Vogels('Birds'),Koekkoek('Cuckoo') andDevalck('The Falcon'); to a desired social status; e.g.,Prins('Prince'),De Koninck/Koning('King'),De Keyzer/Keizer('Emperor'); or to colour; e.g.Rood('red'),Blauw/Blaauw('blue'),De Wit('the white'). There is also a set of made up or descriptive names; e.g.Naaktgeboren('born naked').

Culture

[edit]

Religion

[edit]Prior to the arrival of Christianity, the ancestors of the Dutch adhered to a form ofGermanic paganismaugmented with variousCeltic elements.At the start of the 6th century, the first (Hiberno-Scottish) missionaries arrived. They were later replaced byAnglo-Saxon missionaries,who eventually succeeded in converting most of the inhabitants by the 8th century.[80]Since then, Christianity has been the dominant religion in the region.

In the early 16th century, the ProtestantReformationbegan to form and soon spread in theWesthoekand the County of Flanders, where secret open-air sermons were held, calledhagenpreken('hedgeroworations') in Dutch. The ruler of the Dutch regions,Philip II of Spain,felt it was his duty to fight Protestantism and, afterthe wave of iconoclasm,sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Low Countries a Catholic region once more.[81]The Protestants in the southern Low Countries fled Northen masse.[81]Most of the Dutch Protestants were now concentrated in the free Dutch provinces north of the riverRhine,while the Catholic Dutch were situated in the Spanish-occupied or -dominated South. After thePeace of Westphaliain 1648, Protestantism did not spread South, resulting in a difference in religious situations.

Contemporary Dutch, according to a 2017 study conducted by Statistics Netherlands, are mostly irreligious with 51% of the population professing no religion. The largest Christian denomination with 24% are theRoman Catholics,followed by 15%Protestants.Furthermore, there are 5% Muslims and 6% others (among others Buddhists).[82]People of Dutch ancestry in the United States and South Africa are generally more religious than their European counterparts; for example, the numerous Dutch communities ofwestern Michiganremain strongholds of theReformed Church in Americaand theChristian Reformed Church,both descendants of theDutch Reformed Church.

Cultural divergences

[edit]One cultural division within Dutch culture is that between the formerly Protestant North and the nowadays Catholic South, which encompasses various cultural differences between the Northern Dutch on one side and the Southern Dutch on the other. This subject has historically received attention from historians, notablyPieter Geyl(1887–1966) and Carel Gerretson (1884–1958). The historical pluriformity of the Dutch cultural landscape has given rise to several theories aimed at both identifying and explaining cultural divergences between different regions. One theory, proposed by A.J. Wichers in 1965, sees differences in mentality between the southeastern, or 'higher', and northwestern, or 'lower' regions within the Netherlands, and seeks to explain these by referring to the different degrees to which these areas were feudalised during the Middle Ages.[83]Another, more recent cultural divide is that between theRandstad,the urban agglomeration in the West of the country, and the other provinces of the Netherlands.

In Dutch, the cultural division between North and South is also referred to by thecolloquialism"below/above the great rivers"as the riversRhineandMeuseroughly form a natural boundary between the Northern Dutch (those Dutch living North of these rivers), and the Southern Dutch (those living South of them). The division is partially caused by (traditional) religious differences, with the North used to be predominantly Protestant and the South still having a majority of Catholics. Linguistic (dialectal) differences (positioned along the Rhine/Meuse rivers) and to a lesser extent, historical economic development of both regions are also important elements in any dissimilarity.

On a smaller scale cultural pluriformity can also be found; be it in local architecture or (perceived) character. This wide array of regional identities positioned within such a relatively small area, has often been attributed to the fact that many of the current Dutch provinces were de facto independent states for much of their history, as well as the importance of local Dutch dialects (which often largely correspond with the provinces themselves) to the people who speak them.[84]

Northern Dutch culture

[edit]

Northern Dutch culture is marked byProtestantism,especiallyCalvinism.Though today many do not adhere to Protestantism anymore, or are only nominally part of a congregation, Protestant-(influenced) values and customs are present. Generally, it can be said that the Northern Dutch are morepragmatic,favor a direct approach, and display a less-exuberant lifestyle when compared to Southerners.[86]On a global scale, the Northern Dutch have formed the dominant vanguard of the Dutch language and culture since thefall of Antwerp,exemplified by the use of "Dutch" itself as thedemonymfor the country in which they form a majority; theNetherlands.Linguistically, Northerners speak any of theHollandic,Zeelandic,andDutch Low Saxondialects natively, or are influenced by them when they speak the Standard form of Dutch. Economically and culturally, the traditional centre of the region have been the provinces ofNorthandSouth Holland,or today; theRandstad,although for a brief period during the 13th or 14th century it lay more towards the east, when various eastern towns and cities aligned themselves with the emergingHanseatic League.The entire Northern Dutch cultural area is located in theNetherlands,its ethnically Dutch population is estimated to be just under 10,000,000.[note 2]Northern Dutch culture has been less under French influence than the Southern Dutch culture area.[87]

Frisians

[edit]Frisians, specificallyWest Frisians,are an ethnic group present in the north of the Netherlands, mainly concentrated in the province ofFriesland.Culturally, modern Frisians and the (Northern) Dutch are rather similar; the main and generally most important difference being that Frisians speak West Frisian, one of the three sub-branches of theFrisian languages,alongside Dutch, and they find this to be a defining part of their identity as Frisians.[88]

According to a 1970 inquiry, West Frisians identified themselves more with the Dutch than withEast FrisiansorNorth Frisians.[89]A study in 1984 found that 39% of the inhabitants of Friesland considered themselves "primarily Frisian," although without precluding also being Dutch. A further 36 per cent claimed they were Dutch, but also Frisian, the remaining 25% saw themselves as only Dutch.[90]A 2013 study showed that 45% of the population of Friesland saw themselves as "primarily Frisian", again without precluding the possibility of also identifying as Dutch.[91]Frisians are not disambiguated from the Dutch people in Dutch officialstatistics.[92]

In the Netherlands itself "West-Frisian" refers to the Hollandic dialect, with a Frisian substrate, spoken in the northern part of the province of North-Holland known as West-Friesland, as well as "West-Frisians" referring to its speakers, not to the language or inhabitants of the Frisian part of the country. Historically the whole Dutch North Seacoast was known as Frisia.

Southern Dutch culture

[edit]

The Southern Dutch sphere generally consists of the areas in which the population was traditionally Catholic. During the earlyMiddle Agesup until theDutch Revolt,the Southern regions were more powerful, as well as more culturally and economically developed.[86]At the end of the Dutch Revolt, it became clear theHabsburgswere unable to reconquer the North, while the North's military was too weak to conquer the South, which, under the influence of theCounter-Reformation,had started to develop a political and cultural identity of its own.[93]The Southern Dutch, including Dutch Brabant and Limburg, remained Catholic or returned to Catholicism. The Dutch dialects spoken by this group areBrabantic,Kleverlandish,LimburgishandEastandWest Flemish.In the Netherlands, an oft-used adage used for indicating this cultural boundary is the phraseboven/onder de rivieren(Dutch: above/below the rivers), in which 'the rivers' refer to theRhineand theMeuse.Southern Dutch culture has been influenced more by French culture, as opposed to the Northern Dutch culture area.[87]

Flemings

[edit]Within the field ofethnography,it is argued that the Dutch-speaking populations of the Netherlands and Belgium have a number of common characteristics, with a mostly sharedlanguage,some generally similar or identicalcustoms,and with no clearly separateancestral originororigin myth.[94]

However, the popular perception of being a single group varies greatly, depending on subject matter, locality, and personal background. Generally, the Flemish will seldom identify themselves as being Dutch and vice versa, especially on a national level.[95]This is partly caused by the popular stereotypes in the Netherlands as well as Flanders, which are mostly based on the "cultural extremes" of both Northern and Southern culture, including in religious identity. Though these stereotypes tend to ignore the transitional area formed by the Southern provinces of the Netherlands and most Northern reaches of Belgium, resulting in overgeneralisations.[96]This self-perceived split between Flemings and Dutch, despite the common language, may be compared to howAustriansdo not consider themselves to beGermans,despite the similarities they share with southern Germans such asBavarians.In both cases, the Catholic Austrians and Flemish do not see themselves as sharing the fundamentally Protestant-based identities of their northern counterparts.

In the case of Belgium, there is the added influence ofnationalismas the Dutch language and culturewere oppressedby thefrancophonegovernment. This was followed by anationalist backlashduring the late 19th and early 20th centuries that saw little help from the Dutch government (which for a long time following theBelgian Revolutionhad a reticent and contentious relationship with the newly formed Belgium and a largely indifferent attitude towards its Dutch-speaking inhabitants)[97]and, hence, focused on pitting "Flemish" culture against French culture, resulting in the forming of the Flemishnationwithin Belgium, a consciousness of which can be very marked among some Dutch-speaking Belgians.[98]

Genetics

[edit]

The largest patterns ofhuman genetic variationwithin the Netherlands show strong correlations with geography and distinguish between: (1) North and South; (2) East and West; and (3) the middle-band and the rest of the country. The distribution of gene variants for eye colour, metabolism, brain processes, body height and immune system show differences between these regions that reflectevolutionary selection pressures.[99]

The largest genetic differences within the Netherlands are observed between the North and the South (with the threemajor rivers– Rijn, Waal, Maas – as a border), with theRandstadshowing a mixture of these two ancestral backgrounds. The European North-South cline correlates highly with this Dutch North-South cline and shows several other similarities, such as a correlation with height (with the North being taller on average), blue/brown eye colour (with the North having more blue eyes), and genome-wide homozygosity (with the North having lowerhomozygositylevels). The correlation with genome-wide homozygosity likely reflects theserial founder effectthat was initiated with the ancient successive out-of-Africa migrations. This does not necessarily mean that these events (north-ward migration and evolutionary selection pressures) took place within the borders of the Netherlands; it could also be that Southern Europeans have migrated more to the South of the Netherlands, and/or Northern Europeans more to the Northern parts.[99]

The north–south differences were likely maintained by the relatively strongsegregationof theCatholicSouth and theProtestantNorth during the last centuries. During the last 50 years or so there was a large increase ofnon-religiousindividuals in the Netherlands. Their spouses are more likely to come from a different genetic background than those of religious individuals, causing non-religious individuals to show lower levels of genome-widehomozygositythan Catholics or Protestants.[100]

Dutch diaspora

[edit]

Since World War II, Dutchemigrantshave mainly departed the Netherlands for Canada, the Federal Republic of Germany, the United States, Belgium, Australia, and South Africa, in that order. Today, large Dutch communities also exist in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Turkey, and New Zealand.[28]

Central and Eastern Europe

[edit]During theGerman eastward expansion(mainly taking place between the 10th and 13th century),[101]a number of Dutchmen moved as well. They settled mainly east of theElbeandSaalerivers, regions largely inhabited byPolabian Slavs.[102]After the capture of territory along the Elbe and Havel Rivers in the 1160s, Dutch settlers from flooded regions inHollandused their expertise to build dikes inBrandenburg,but also settled in and around major German cities such asBremenandHamburgand German regions ofMecklenburgand Brandenburg.[103]From the 13th to the 15th centuries, theTeutonic Orderinvited several waves of Dutch and Frisians to settle throughoutPrussia,mainly along theBaltic Seacoast.[104]The first place in modernPolandwhere Dutch immigrants settled wasPasłękin 1297, once renamedHolądafter the settlers.[105]

In the early-to-mid-16th century, DutchMennonitesbegan to move from theLow Countries(especiallyFrieslandandFlanders) to theVistuladelta region, seeking religious freedom and exemption from military service.[106]The territories which they settled were located in the regions ofPomereliaandPowiślein northern Poland, and later also inMasoviain central Poland.[107]These communities became known as theOlęders,a Polish rendering of the termHollander.[108]After thepartitions of Poland,thePrussianauthorities took over and its government eliminated exemption from military service on religious grounds.

The DutchMennonitesalso migrated as far as theRussian Empire,where they were offered land along theVolga River.Some settlers left forSiberiain search for fertile land.[109]The Russian capital itself,Moscow,also had a number of Dutch immigrants, mostly working as craftsmen. Arguably the most famous of which wasAnna Mons,the mistress ofPeter the Great.

Historically Dutch also lived directly on the eastern side of the German border, most have since been assimilated (apart from ~40,000 recent border migrants), especially since the establishment of Germany itself in 1872. Cultural marks can still be found though. In some villages and towns aDutch Reformedchurch is present, and a number of border districts (such asCleves,BorkenandViersen) have towns and village with an etymologically Dutch origin. In the area aroundCleves(GermanKleve,DutchKleef)traditional dialectis Dutch, rather than surrounding(High/Low) German.More to the South, cities historically housing many Dutch traders have retained Dutchexonymsfor exampleAachen(Aken) and Cologne/Köln (Keulen) to this day.

Southern Africa

[edit]

AlthoughPortugueseexplorers made contact with theCape of Good Hopeas early as 1488, much of present-daySouth Africawas ignored by Europeans until theDutch East India Company(VOC) established its first outpost atCape Town,in 1652.[110][111]Dutch colonisers began arriving shortly thereafter, making the Cape home to the oldest Western-based civilisation south of theSahara.[112]Some of the earliest mulatto communities in the country were subsequently formed through unions between colonists, enslaved people, and variousKhoikhoitribes.[113]This led to the development of a major South African ethnic group,Cape Coloureds,who adopted the Dutch language and culture.[111]As the number of Europeans—particularly women—in the Cape swelled, South African whites closed ranks as a community to protect their privileged status, eventually marginalising Coloureds as a separate and inferior racial group.[114]

Since VOC employees proved inept farmers, tracts of land were granted to married Dutch citizens who undertook to spend at least twenty years in South Africa.[115]Upon the revocation of theEdict of Nantesin 1685, they were joined by FrenchHuguenotsfleeing religious persecution at home, who interspersed among the original freemen.[110]Between 1685 and 1707 the company also extended free passage to any Dutch families wishing to resettle at the Cape.[116]At the beginning of the eighteenth century there were roughly 600 people of Dutch birth or descent residing in South Africa, and around the end of Dutch rule in 1806 the number had reached 13,360.[117]

Somevrijburgerseventually turned to cattle ranching astrekboers,creating their own distinct sub-culture centered around a semi-nomadic lifestyle and isolated patriarchal communities.[112]By the eighteenth century there had emerged a new people in Africa who identified asAfrikaners,rather than Dutchmen, after the land they had colonised.[118]

Afrikaners are dominated by two main groups, theCape DutchandBoers,which are partly defined by different traditions of society, law, and historical economic bases.[112]Although their language (Afrikaans) and religion remain undeniably linked to that of the Netherlands,[119]Afrikaner culture has been strongly shaped by three centuries in South Africa.[118]Afrikaans, which developed fromEarly Modern Dutch,has been influenced by English,Malay-Portuguese creole,and various African languages. Dutch was taught to South African students as late as 1914 and a few upper-class Afrikaners used it in polite society, but the first Afrikaans literature had already appeared in 1861.[112]TheUnion of South Africagranted Dutch official status upon its inception, but in 1925 Parliament openly recognised Afrikaans as a separate language.[112]It differs from Standard Dutch by several pronunciations borrowed from Malay, German, or English, the loss of case and gender distinctions, and in the extreme simplification of grammar.[120]The dialects are no longer considered quite mutually intelligible.[121]

During the 1950s, Dutch immigration to South Africa began to increase exponentially for the first time in over a hundred years. The country registered a net gain of around 45,000 Dutch immigrants between 1950 and 2001, making it the sixth most popular destination for citizens of the Netherlands living abroad.[28]

Southeast Asia

[edit]

Since the 16th century, there has been a Dutch presence inSoutheast Asia,Taiwan, andJapan.In many cases, the Dutch were the first Europeans whom the people living there encountered. Between 1602 and 1796, the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in its territories in Asia.[122]The majority died of disease or made their way back to Europe, but some of them made the Indies their new home.[123]Interaction between the Dutch and the indigenous populations mainly took place inSri Lankaand themodern Indonesian Islands.Most of the time, Dutch soldiers married local women and settled in the colonies. Through the centuries, there developed a relatively large Dutch-speaking population of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent, known asIndosor Dutch-Indonesians. The expulsion of Dutchmen following theIndonesian Revoltmeans that currently[when?]the majority of this group lives in the Netherlands. Statistics show that Indos are the largest minority group in the Netherlands and number close to half a million (excluding the third generation).[124]

West Africa

[edit]Though many Ghanaians of European origin are mostly of British origin, there are a small number of Dutch people in Ghana. The forts in Ghana have a small number of a Dutch population. The most of the Dutch population is held inAccra,where the Netherlands has its embassy.

Australia and New Zealand

[edit]

Though the Dutch were the firstEuropeansto visit Australia and New Zealand, colonisation did not take place and it was only afterWorld War IIthat a sharp increase in Dutch emigration to Australia occurred. Poor economic prospects for many Dutchmen as well as increasing demographic pressures, in the post-war Netherlands were a powerful incentive to emigrate. Due to Australia experiencing a shortage ofagriculturalandmetal industryworkers it, and to a lesser extent New Zealand, seemed an attractive possibility, with the Dutch government actively promoting emigration.[125]

The effects of Dutch migration to Australia can still be felt. There are many Dutch associations and a Dutch-language newspaper continues to be published. The Dutch have remained a tightly knit community, especially in the large cities. In total, about 310,000 people of Dutch ancestry live in Australia whereas New Zealand has some 100,000 Dutch descendants.[125]

North America

[edit]

The Dutch had settled in North America long before the establishment of the United States of America.[126]For a long time the Dutch lived in Dutch colonies (New Netherland settlements), owned and regulated by the Dutch Republic, which later became part of theThirteen Colonies.

Nevertheless, many Dutch American communities remained virtually isolated towards the rest of North America up until theAmerican Civil War,in which the Dutch fought for the North and adopted many American ways.[127]

Most future waves of Dutch immigrants were quickly assimilated. There have been five U.S. presidents of Dutch descent:Martin Van Buren(8th, first president who was not of British descent, first language was Dutch),Franklin D. Roosevelt(32nd, elected to four terms in office, he served from 1933 to 1945, the only U.S. president to have served more than two terms),Theodore Roosevelt(26th), as well asGeorge H. W. Bush(41st) andGeorge W. Bush(43rd), the latter two descendant from theSchuyler family.

The first Dutch people to come to Canada wereDutch Americansamong theUnited Empire Loyalists.The largest wave was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when large numbers of Dutch helped settle theCanadian west.During this period significant numbers also settled in major cities likeToronto.

While interrupted by World War I, this migration returned in the 1920s, but again halted during theGreat Depressionand World War II. After the war a large number of Dutch immigrants moved to Canada, including a number ofwar bridesof the Canadian soldiers who liberated the Netherlands. There were officially 1,886 Dutch war brides emigrating to Canada, ranking second after British war brides.[128]During the war Canada had shelteredCrown Princess Julianaand her family. Due to theseclose linksduring and after the war, Canada became a popular destination for Dutch immigrants.[129]

South America

[edit]

In South America, the Dutch settled mainly inBrazil,ArgentinaandSuriname.[130][131]

The Dutch were among the firstEuropeanssettling in Brazil during the 17th century. They controlled thenortherncoast of Brazil from 1630 to 1654 (Dutch Brazil). A significant number of Dutch immigrants arrived in that period. The state ofPernambuco(thenCaptaincy of Pernambuco) was once a colony of theDutch Republicfrom 1630 to 1661. There are a considerable number of people who are descendants of the Dutch colonists inParaíba(for example in Frederikstad, todayJoão Pessoa), Pernambuco,AlagoasandRio Grande do Norte.[132][133]During the 19th and 20th century, Dutch immigrants from theNetherlandsimmigrated to the Brazil'sCenter-South,where they founded a few cities.[134]The majority of Dutch Brazilians reside in the states ofEspírito Santo,Paraná,[135]Rio Grande do Sul,PernambucoandSão Paulo.[136]There are also small groups of Dutch Brazilians inGoiás,Ceará,Rio Grande do Norte,Mato Grosso do Sul,Minas GeraisandRio de Janeiro.[137][138][130]

In Argentina, Dutch immigration has been one of many migration flows from Europe in the country, although it has not been as numerous as in other cases (they failed to account for 1% of total migration received). However, Argentina received a large contingent of Dutch since 1825. The largest community is in the city ofTres Arroyosin the south of theprovince of Buenos Aires.[131]

In Suriname the Dutch migrant settlers in search of a better life started arriving in the 19th century with theboeroes,poor farmers arriving from theDutch provincesofGelderland,Utrecht,andGroningen.[139]Furthermore, the Surinamese ethnic group, theCreoles,persons of mixedAfrican-Europeanancestry, are partially of Dutch descent. Many Dutch settlers left Suriname after independence in 1975, which diminished the white Dutch population in the country. Currently there are around 1000 boeroes left in Suriname, and 3000 outside Suriname. Inside Suriname, they work in several sectors of society and some families still work in the agricultural sector.[140]

See also

[edit]- Afrikaner

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Chilean

- Dutch Mexicans

- Dutch customs and etiquette

- Dutch Surinamese

- Flemish people

- List of Dutch people

- List of Germanic peoples

- Netherlands (terminology)

- Netherlands Antilles

- New Netherlands

- Dutch American

- Dutch cuisine

- Dutch culture

Notes

[edit]- ^abIn the 1950s (the peak of traditional emigration) about 350,000 people left the Netherlands, mainly toAustralia,New Zealand,Canada,theUnited States,ArgentinaandSouth Africa.About one-fifth returned. The maximum Dutch-born emigrant stock for the 1950s is about 300,000 (some have died since). The maximum emigrant stock (Dutch-born) for the period after 1960 is 1.6 million. Discounting pre-1950 emigrants (who would be about 85 or older), at most around 2 million people born in the Netherlands are now living outside the country. Combined with the 13.2 million ethnically Dutch inhabitants of the Netherlands (both parents born in the Netherlands),[1]there are about 16 million people who are Dutch (of Dutch ancestry), in a minimally accepted sense.Autochtone population at 1 January 2006, Central Statistics Bureau, Integratiekaart 2006,(in Dutch)

- ^Estimate based on the population of the Netherlands, without the southern provinces and non-ethnic Dutch.

- ^Dutch Low Saxon,a variety ofLow Germanspoken in northeastern Netherlands, is used by people who ethnically identify as "Dutch" despite perceived linguistic differences.

- ^Limburgish,aLow Franconianvariety in close proximity to bothDutchandGerman,spoken in southeastern Netherlands is used by people who ethnically identify as Dutch orFlemingsand regionally as "Limburgers" despite perceived linguistic differences.

- ^West Frisian is spoken by the ethnicFrisians,who may or may not also identify as "Dutch".

- ^The Caribbean Netherlands are treated as a municipality of the Netherlands and the inhabitants are considered in law and practice to be "Dutch", even if they might not identify as such personally.

- ^Papiamento, aPortuguese-based creole,is spoken byArubansandCuraçaoanswho may ethnically further also identify as "Dutch".

References

[edit]- ^abcd"Bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd en nationaliteit op 1 januari; 1995-2023"(in Dutch).Statistics Netherlands.2 June 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2023.Retrieved20 December2023.

- ^"Table B04006 – People Reporting Ancestry – 2021 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates".United States Census Bureau.2021.Archivedfrom the original on 1 June 2023.Retrieved1 September2023.

- ^"Afrikaners constitute nearly three million out of approximately 53 million inhabitants of the Republic of South Africa, plus as many as half a million in diaspora."AfrikanerArchived28 November 2017 at theWayback Machine– Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^Afrikaners make up approximately 5.2% of the total South African population based on the number ofwhite South Africanswho speak Afrikaans as a first language in theSouth African National Census of 2011.

- ^"Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables".Statcan.gc.ca.25 October 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2017.Retrieved7 January2020.

- ^"ABS Ancestry".Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 22 May 2019.Retrieved16 August2013.

- ^"More Than 250,000 Dutch People in Germany".Destatis.de.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2019.Retrieved31 January2022.

- ^"Number of people with the Dutch nationality in Belgium as reported by Statistic Netherlands"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 July 2017.Retrieved8 March2022.

- ^"New Zealand government website on Dutch-Australians".Teara.govt.nz.4 March 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2019.Retrieved10 September2012.

- ^res."Présentation des Pays-Bas".Diplomatie.gouv.fr(in French).Archivedfrom the original on 18 June 2020.Retrieved19 June2020.

- ^"Estimated overseas-born population resident in the United Kingdom by sex, by country of birth (Table 1.4)".Office for National Statistics.28 August 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2015.Retrieved9 April2015.

- ^abcdefghijklm"Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination".migrationpolicy.org.10 February 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 19 March 2022.Retrieved23 February2021.

- ^abcJoshua Project."Dutch Ethnic People in all Countries".Joshua Project.Archivedfrom the original on 7 January 2019.Retrieved7 August2012.

- ^"Archived copy"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 3 March 2016.Retrieved18 March2015.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^"CBS – One in eleven old age pensioners live abroad – Web magazine".Cbs.nl. 20 February 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 5 February 2012.Retrieved7 August2012.

- ^"Table 5 Persons with immigrant background by immigration category, country background and sex. 1 January 2009".Ssb.no. 1 January 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 15 November 2011.Retrieved7 August2012.

- ^"SEF: Relatório de Imigração, Fronteiras e Asilo 2022"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 July 2023.Retrieved22 July2023.

- ^"Taal in Nederland.:. Nedersaksisch".taal.phileon.nl(in Dutch). Archived fromthe originalon 13 February 2017.Retrieved3 January2020.

- ^"Regeling – Instellingsbesluit Consultatief Orgaan Fries 2010 – BWBR0027230".Wetten.overheid.nl(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 6 November 2014.Retrieved3 January2020.

- ^"Taal in Nederland.:. Fries".taal.phileon.nl(in Dutch). Archived fromthe originalon 13 February 2017.Retrieved3 January2020.

- ^ab"Regeling – Invoeringswet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba – BWBR0028063".Wetten.overheid.nl(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 25 February 2021.Retrieved3 January2020.

- ^"Regeling – Wet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba – BWBR0028142".Wetten.overheid.nl(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 6 November 2014.Retrieved3 January2020.

- ^Schmeets, Hans (2016).De religieuze kaart van Nederland, 2010–2015(PDF).Centraal Bureau voor der Statistiek. p. 5.Archived(PDF)from the original on 15 October 2017.Retrieved12 December2021.

- ^"Helft Nederlanders is kerkelijk of religieus".Cbs.nl(in Dutch). 22 December 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 14 July 2019.Retrieved17 October2017.

- ^Numbers, Ronald L. (2014).Creationism in Europe.JHU Press.ISBN978-1-4214-1562-8.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023.Retrieved10 November2020.

- ^Based onStatistics Canada,Canada 2001 Census.Linkto Canadian statistics.Archived25 February 2005 at theWayback Machine

- ^"2001CPAncestryDetailed (Final)"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 7 September 2013.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^abcNicholaas, Han; Sprangers, Arno."Dutch-born 2001, Figure 3 in DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens".Nidi.knaw.nl. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 11 June 2007.

- ^According toFactfinder.census.govArchived11 February 2020 atarchive.today

- ^Winkler Prins Geschiedenis der NederlandenI (1977), p. 150; I.H. Gosses,Handboek tot de staatkundige geschiedenis der NederlandenI (1974 [1959]), 84 ff.

- ^The actual independence was accepted by in the 1648 treaty of Munster, in practice the Dutch Republic had been independent since the last decade of the 16th century.

- ^D.J. Noordam, "Demografische ontwikkelingen in West-Europa van de vijftiende tot het einde van de achttiende eeuw",in H.A. Diederiks e.a.,Van agrarische samenleving naar verzorgingsstaat(Leiden 1993), 35–64, esp. 40

- ^"CBS statline Church membership".Statline.cbs.nl. 15 December 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 23 September 2018.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^Religion in the NetherlandsArchived16 January 2013 at theWayback Machine.(in Dutch)

- ^"Wat maakt Nederland tot Nederland? Over identiteit blijken we verrassend eensgezind".trouw.nl. 26 June 2019.Retrieved17 July2022.

- ^"Clovis' conversion to Christianity, regardless of his motives, is a turning point in Dutch history as the elite now changed their beliefs. Their choice would way down its way on the common folk, of whom many (especially in the Frankish heartland of Brabant and Flanders) were less enthusiastic than the ruling class." Taken fromGeschiedenis van de Nederlandse stam,part I: till 1648. Page 203, 'A new religion', byPieter Geyl.Wereldbibliotheek Amsterdam/Antwerp1959.

- ^Britannica: "They were divided into three groups: the Salians, the Ripuarians, and the Chatti, or Hessians." (LinkArchived3 May 2015 at theWayback Machine)

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009Archived15 February 2014 at theWayback Machine;The Franks, who had settled in Toxandria, in Brabant, were given the job of defending the border areas, which they did until the mid-5th century

- ^Arblaster, Paul (26 October 2018).A History of the Low Countries.Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 39.ISBN978-1-137-61188-8.Retrieved3 March2024.

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'Dutch language' 10 May. 2009Archived26 April 2015 at theWayback Machine;"It derives from Low Franconian, the speech of the Western Franks, which was restructured through contact with speakers of North Sea Germanic along the coast."

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'West Germanic languages'. 10 May. 2009Archived30 August 2011 at theWayback Machine;restructured Frankish—i.e., Dutch;

- ^W. Pijnenburg, A. Quak, T. Schoonheim & D. Wortel, Oudnederlands Woordenboek.Archived19 January 2016 at theWayback Machine

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009Archived15 February 2014 at theWayback Machine;"The administrative organization of the Low Countries... was basically the same as that of the rest of the Frankish empire."

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009Archived15 February 2014 at theWayback Machine;"During the 6th century, Salian Franks had settled in the region between the Loire River in present-day France and the Coal Forest in the south of present-day Belgium. From the late 6th century, Ripuarian Franks pushed from the Rhineland westward to the Schelde. Their immigration strengthened the Germanic faction in that region, which had been almost completely evacuated by the Gallo-Romans."

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'Fleming and Walloon'. 12 May. 2009Archived28 April 2009 at theWayback Machine;"The northern Franks retained their Germanic language (which became modern Dutch), whereas the Franks moving south rapidly adopted the language of the culturally dominant Romanized Gauls, the language that would become French. The language frontier between northern Flemings and southern Walloons has remained virtually unchanged ever since."

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online (use fee site); entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009Archived15 February 2014 at theWayback Machine;Thus, the town in the Low Countries became acommunitas(sometimes calledcorporatiooruniversitas)—a community that was legally a corporate body, could enter into alliances and ratify them with its own seal, could sometimes even make commercial or military contracts with other towns, and could negotiate directly with the prince.

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009Archived15 February 2014 at theWayback Machine;The development of a town's autonomy sometimes advanced somewhat spasmodically because of violent conflicts with the prince. The citizens then united, formingconjurationes(sometimes called communes)—fighting groups bound together by an oath—as happened during a Flemish crisis in 1127–28 in Ghent and Brugge and in Utrecht in 1159.

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009Archived15 February 2014 at theWayback Machine;All the towns formed a new, non-feudal element in the existing social structure, and from the beginning merchants played an important role. The merchants often formed guilds, organizations that grew out of merchant groups and banded together for mutual protection while traveling during this violent period, when attacks on merchant caravans were common.

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009Archived15 February 2014 at theWayback Machine;The achievements of the Flemish partisans inspired their colleagues in Brabant and Liège to revolt and raise similar demands; Flemish military incursions provoked the same reaction in Dordrecht and Utrecht

- ^abEtymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands,entry"Diets".(in Dutch)

- ^Becker, Uwe (2006).J. Huizinga (1960: 62).Het Spinhuis.ISBN978-90-5589-275-4.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^Cf. G. Parker,The Dutch Revolt(1985), 33–36, and Knippenberg & De Pater,De eenwording van Nederland(1988), 17 ff.

- ^Source, the aforementioned 3rd chapter (p3), together with the initial paragraphs of chapter 4, on the establishment of the Dutch Republic.

- ^Oostendorp, Marc van (1 June 2018)."Nederland of Holland?".Neerlandistiek(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023.Retrieved1 September2023.

- ^"Wennen aan The Netherlands, want Holland bestaat niet langer".nos.nl(in Dutch). 31 December 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023.Retrieved1 September2023.

- ^margoD (3 September 2020)."Wat is het verschil tussen Holland en Nederland?".When in Holland(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023.Retrieved1 September2023.

- ^Shetter (2002), 201

- ^J. Knipscheer and R. Kleber,Psychologie en de multiculturele samenleving(Amsterdam 2005), 76 ff.

- ^cf.Pan-Germanism,Pan-Slavismand many otherGreater state movementsof the day.

- ^Het nationaal-socialistische beeld van de geschiedenis der NederlandenArchived27 April 2023 at theWayback Machineby I. Schöffer. Amsterdam University Press. 2006. Page 92.

- ^For example he gave explicit orders not to create a voluntary Greater DutchWaffen SSdivision composed of soldiers from the Netherlands and Flanders. (Link to documentsArchived22 March 2012 at theWayback Machine)

- ^"Maltho thi afrio lito"is the oldest attested(Old) Dutchsentence, found in the Salic Law, a legal text written around 500. (Source: theOld Dutch dictionaryArchived27 April 2023 at theWayback Machine)(in Dutch)

- ^TaaluniversumwebsiteArchived28 September 2023 at theWayback Machineon the Dutch dialects and main groupings.(in Dutch)

- ^Hüning, Matthias."Kaart van de Nederlandse dialecten"[Map of Dutch dialects].University of Vienna(in Dutch). Archived fromthe originalon 10 December 2006.

- ^Nicoline Sijs van der (2009).Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages.Amsterdam University Press. p. 50.

Martin van Buren's mother tongue was Dutch

- ^Edward L. Widmer(2005).Martin Van Buren.The American Presidents Series. Times Books. pp. 6–7.

Van Buren grew up speaking Dutch, a relic of the time before the Revolution when the inland waterways of North America were a polyglot blend of non-Anglophone communities. His family has resisted intermarriage with Yankees for five generations, and Van Buren trumpeted the fact proudly in his autobiography

- ^2006 New Zealand Census.

- ^As many as 100,000 New Zealanders are estimated to have Dutch blood in their veinsArchived1 May 2008 at theWayback Machine(some 2% of the current population of New Zealand).

- ^Until World War II,Nederlanderwas used synonym withDiets.However the similarity toDeutschresulted in its disuse when theGerman occupiersand Dutchfascistsextensively used that name to stress the Dutch as an ancient Germanic people. (Source:Etymologisch Woordenboek)(in Dutch)

- ^See J. Verdam,Middelnederlandsch handwoordenboek(The Hague 1932 (reprinted 1994)): "Nederlant, znw. o. I) Laag of aan zee gelegen land. 2) het land aan den Nederrijn; Nedersaksen, -duitschland."(in Dutch)

- ^"Hermes in uitbreiding".Users.pandora.be.Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2008.Retrieved7 October2017.

- ^neder-corresponds with the Englishnether-,which means "low" or "down".

- ^"Online Etymology Dictionary".Archived fromthe originalon 6 December 2008.Retrieved6 November2008.

- ^Hoitink, Y. (10 April 2005)."Prefixes in surnames".Dutch Genealogy.Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2023.Retrieved15 August2019.

- ^"Hoofdletters in namen: Nynke van der Sluis / Nynke Van der Sluis".Onze Taal(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2023.Retrieved12 September2023.

- ^DBNL."[Nummer 12], Onze Taal. Jaargang 29".DBNL(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2021.Retrieved12 September2023.

- ^See the history section of theVanderbilt familyarticle, or visit thislink.Archived20 May 2006 at theWayback Machine

- ^"It is a common mistake of Americans, oranglophonesin general, to think that the 'van' in front of a Dutch name signifies nobility. "(Source.Archived11 June 2007 at theWayback Machine); "Vonmay be observed in German names denoting nobility while thevan,van der,van deandvan den(whether written separately or joined, capitalized or not) stamp the bearer as Dutch and merely mean 'at', 'at the', 'of', 'from' and 'from the' "(Source: Genealogy.comArchived22 June 2007 at theWayback Machine), (Institute for Dutch surnamesArchived8 November 2007 at theWayback Machine,inDutch)

- ^Most common names of occupational origin. Source 1947 Dutch census.(in Dutch)

- ^The Anglo-Saxon ChurchArchived12 May 2017 at theWayback Machine–Catholic Encyclopediaarticle

- ^abThe Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806,ISBN0-19-820734-4

- ^"Meer dan de helft Nederlanders niet religieus"(PDF).Cbs.nl.Archived fromthe originalon 6 July 2017.Retrieved8 March2022.

- ^A.M. van der Woude,Nederland over de schouder gekeken(Utrecht 1986), 11–12.(in Dutch)

- ^Dutch Culture in a European Perspective; by D. Fokkema, 2004, Assen.

- ^abThis image is based on the rough definition given by in the 2005 "number 3" edition of the magazine "Neerlandia" by theANV;it states the dividing line between both areas lies where "the great rivers divide the Brabantic from the Hollandic dialects and where Protestantism traditionally begins".

- ^abVoor wie Nederland en Vlaanderen wil leren kennen.1978 By J. Wilmots

- ^abFred M. Shelley, Nation Shapes: The Story Behind the World's Borders, 2013, page 97

- ^"Ynterfryske ferklearring (Inter-Frisian Declaration)".De Fryske Rie (The Frisian Council)(in Western Frisian).Archivedfrom the original on 27 September 2018.Retrieved5 January2020.

Wy wolle ús taal, dy't foar ús identiteit beskiedend is, befoarderje en útbouwe. (We want to promote and develop our language, which is defining for our identity)

- ^Frisia. 'Facts and fiction' (1970), by D. Tamminga.(in Dutch)

- ^Mahmood, Cynthia; Armstrong, Sharon L K (January 1992). "Do Ethnic Groups Exist?: A Cognitive Perspective on the Concept of Cultures".Ethnology.31(1): 1–14.doi:10.2307/3773438.JSTOR3773438.

- ^Betten, Erik (June 2013).De Friezen: Op syk nei de Fryske identiteit.p. 168.

- ^"Bevolking (Population)".CBS Statline.cbs.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2018.Retrieved2 January2020.

- ^Cf. Geoffrey Parker,The Dutch Revolt:"Gradually a consistent attitude emerged, a sort of 'collective identity' which was distinct and able to resist the inroads, intellectual as well as military, of both the Northern Dutch (especially during the crisis of 1632) and the French. This embryonic 'national identity' was an impressive monument to the government of the archdukes, and it survived almost forty years of grueling warfare (1621–59) and the invasions of Louis XIV until, in 1700, the Spanish Habsburgs died out." (Penguin edition 1985, p. 260). See also J. Israel,The Dutch Republic, 1477–1806,461–463 (Dutch language version).

- ^National minorities in Europe, W. Braumüller, 2003, page 20.

- ^Nederlandse en Vlaamse identiteit, Civis Mundi 2006 by S.W Couwenberg.ISBN90-5573-688-0.Page 62. Quote: "Er valt heel wat te lachen om de wederwaardigheden van Vlamingen in Nederland en Nederlanders in Vlaanderen. Ze relativeren de verschillen en beklemtonen ze tegelijkertijd. Die verschillen zijn er onmiskenbaar: in taal, klank, kleur, stijl, gedrag, in politiek, maatschappelijke organisatie, maar het zijn stuk voor stuk varianten binnen één taal-en cultuurgemeenschap." The opposite opinion is stated by L. Beheydt (2002): "Al bij al lijkt een grondiger analyse van de taalsituatie en de taalattitude in Nederland en Vlaanderen weinig aanwijzingen te bieden voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit. Dat er ook op andere gebieden weinig aanleiding is voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit is al door Geert Hofstede geconstateerd in zijn vermaarde boekAllemaal andersdenkenden(1991). "L. Beheydt," Delen Vlaanderen en Nederland een culturele identiteit? ", in P. Gillaerts, H. van Belle, L. Ravier (eds.),Vlaamse identiteit: mythe én werkelijkheid(Leuven 2002), 22–40, esp. 38.(in Dutch)

- ^Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: Accounting for the past, 1650–2000; by D. Fokkema, 2004, Assen.

- ^Geschiedenis van de Nederlanden,by J.C.H Blom and E. Lamberts,ISBN978-90-5574-475-6;page 383.(in Dutch)

- ^Wright, Sue; Kelly-Holmes, Helen (1 January 1995).Languages in contact and conflict... – Google Books.Multilingual Matters.ISBN978-1-85359-278-2.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^abAbdellaoui, Abdel; Hottenga, Jouke-Jan; de Knijff, Peter; Nivard, Michel; Xiangjun, Xiao; Scheet, Paul; Brooks, Andrew; Ehli, Erik; Hu, Yueshan; Davies, Gareth; Hudziak, James; Sullivan, Patrick; van Beijsterveldt, Toos; Willemsen, Gonneke; de Geus, Eco; Penninx, Brenda; Boomsma, Dorret (27 March 2013)."Population structure, migration, and diversifying selection in the Netherlands".European Journal of Human Genetics.21(11): 1277–1285.doi:10.1038/ejhg.2013.48.PMC3798851.PMID23531865.

- ^Abdellaoui, Abdel; Hottenga, Jouke-Jan; Xiangjun, Xiao; Scheet, Paul; Ehli, Erik; Davies, Gareth; Hudziak, James; Smit, Dirk; Bartels, Meike; Willemsen, Gonneke; Brooks, Andrew; Sullivan, Patrick; Smit, Johannes; de Geus, Eco; Penninx, Brenda; Boomsma, Dorret (25 August 2013)."Association Between Autozygosity and Major Depression: Stratification Due to Religious Assortment".Behavior Genetics.43(6): 455–467.doi:10.1007/s10519-013-9610-1.PMC3827717.PMID23978897.

- ^Taschenatlas Weltgeschichte, part 1, by H. Kinder and W. Hilgemann.ISBN978-90-5574-565-4,page 171. (German)

- ^"Boise State University thesis by E.L. Knox on the German Eastward Expansion ('Ostsiedlung')".Oit.boisestate.edu. Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2008.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^"Nederlandse Kolonies in Duitsland".Home.planet.nl.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023.Retrieved8 March2022.

- ^Thompson, James Westfall (7 October 2017). "Dutch and Flemish Colonization in Mediaeval Germany".American Journal of Sociology.24(2): 159–186.doi:10.1086/212889.JSTOR2763957.S2CID145644640.

- ^Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, Tom III(in Polish). Warszawa. 1882. p. 96.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"Article on Dutch settlers in Poland published by the Polish Genealogical Society of America and written by Z. Pentek".Pgsa.org. Archived fromthe originalon 18 November 2010.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, Tom VI(in Polish). Warszawa. 1885. p. 256.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^Andrzej Chwalba; Krzysztof Zamorski (2020).The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. History, Memory, Legacy.London: Routledge – Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-1-000-20399-8.Archivedfrom the original on 11 April 2023.Retrieved20 March2023.

- ^"Article published by the Mercator Research center on Dutch settlers in Siberia".Archived fromthe originalon 2 January 2014.Retrieved8 March2022.

- ^abThomas McGhee, Charles C.; N/A, N/A, eds. (1989).The plot against South Africa(2nd ed.). Pretoria: Varama Publishers.ISBN0-620-14537-4.

- ^abFryxell, Cole.To Be Born a Nation.pp. 9–327.

- ^abcdeKaplan, Irving.Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa.pp. 42–591.

- ^Nelson, Harold.Zimbabwe: A Country Study.pp. 237–317.

- ^Roskin, Roskin.Countries and concepts: an introduction to comparative politics.pp. 343–373.

- ^Hunt, John (2005). Campbell, Heather-Ann (ed.).Dutch South Africa: Early Settlers at the Cape, 1652–1708.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 13–35.ISBN978-1-904744-95-5.

- ^Keegan, Timothy (1996).Colonial South Africa and the Origins of the Racial Order(1996 ed.). David Philip Publishers (Pty) Ltd. pp.15–37.ISBN978-0-8139-1735-1.

- ^Entry: Cape Colony.Encyclopedia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting.Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1933. James Louis Garvin, editor.

- ^abDowden, Richard (2010).Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles.Portobello Books. pp.380–415.ISBN978-1-58648-753-9.

- ^"Is Afrikaans Dutch?".DutchToday.com. Archived fromthe originalon 24 June 2012.Retrieved10 September2012.

- ^"Afrikaans language – Britannica Online Encyclopedia".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 31 August 2010.Retrieved10 September2012.

- ^"The Afrikaans Language | about | language".Kwintessential.co.uk. Archived fromthe originalon 7 September 2012.Retrieved10 September2012.

- ^"Data".portal.unesco.org.Archived from the original on 17 December 2008.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^"Easternization of the West: Children of the VOC".Dutchmalaysia.net. Archived fromthe originalon 14 August 2009.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^(in Dutch)Willems, Wim, 'De uittocht uit Indie1945–1995' (Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, 2001)ISBN90-351-2361-1

- ^abNederland-Australie 1606–2006 on Dutch emigration.Archived28 June 2010 at theWayback Machine

- ^The U.S. declared its independence in 1776. The first Dutch settlement was built in 1614: Fort Nassau, where presently Albany, New York is positioned.

- ^"How the Dutch became Americans, American Civil War. (includes reference on fighting for the North)".Library.thinkquest.org. Archived fromthe originalon 16 May 2012.Retrieved27 August2010.

- ^Ganzevoort, Herman (1983).Dutch immigration to North America.Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario. p. 192.ISBN0-919045-15-4.Archived fromthe originalon 8 July 2013.

- ^NTR."Emigratie naar Canada".Andere Tijden(in Dutch).Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2023.Retrieved12 September2023.

- ^ab"Imigração Holandesa no Brasil. Glossário. História, Sociedade e Educação no Brasil – HISTEDBR – Faculdade de Educação – UNICAMP".Histedbr.fae.unicamp.br.Archived fromthe originalon 6 August 2013.Retrieved30 August2017.

- ^abEmbajada del Reino de los Países Bajos en Buenos Aires, Argentina."Holandeses en Argentina"(in Spanish). Archived fromthe originalon 14 August 2012.Retrieved7 August2014.

- ^"Brasileiros na Holanda -".Brasileirosnaholanda.com.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2018.Retrieved30 August2017.

- ^"Agência CT – Ministério da Ciência & Tecnologia".Agenciat.mct.gov.br.Archived fromthe originalon 7 May 2016.Retrieved30 August2017.

- ^"Holandeses no Brasil – Radio Nederland, a emissora internacional e independente da Holanda – Português".Parceria.nl.Archived fromthe originalon 23 February 2009.Retrieved30 August2017.

- ^"Cidades preservam tradições dos colonos"[Cities preserve traditions of colonists] (in Portuguese). Bem Paraná. 20 September 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 23 April 2016.Retrieved14 April2016.

- ^"Imigrantes: Holandeses".Terrabrasileira.net.Archived from the original on 29 April 2008.Retrieved30 August2017.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^FIGUEIREDO, Raquel de Freitas. Estudo de SNPs do cromossomo Y na população do Estado do Espirito Santo, Brasil. 2012. 66 f. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Estadual Paulista, Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas, 2012.

- ^"Estudo de SNPs do cromossomo Y na população do Estado do Espirito Santo, Brasil".Base.repositorio.unesp.br.Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2014.Retrieved30 August2017.

- ^America Desde Otra Frontera. LaGuayana Holandesa– Surinam: 1680–1795,Ana Crespo Solana.

- ^F.E.M. Mitrasing (1979).Suriname, Land of Seven Peoples: Social Mobility in a Plural Society, an Ethno-historical Study.p. 35.

Further reading