Emma Lazarus

Emma Lazarus | |

|---|---|

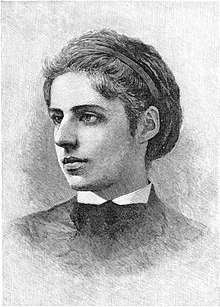

Lazarus,c. 1872 | |

| Born | July 22, 1849 New York City,New York,U.S. |

| Died | November 19, 1887(aged 38) New York City |

| Resting place | Beth Olam CemeteryinBrooklyn,New York City |

| Occupation | Author, activist |

| Language | English |

| Genre | poetry, prose, translations, novels, plays |

| Subject | Georgism |

| Notable works | "The New Colossus" |

| Relatives | Josephine Lazarus,Benjamin N. Cardozo |

| Signature | |

Emma Lazarus(July 22, 1849 – November 19, 1887) was an American author of poetry, prose, and translations, as well as an activist for Jewish andGeorgistcauses. She is remembered for writing thesonnet"The New Colossus",which was inspired by theStatue of Liberty,in 1883.[1]Its lines appear inscribed on abronzeplaque, installed in 1903,[2]on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.[3]Lazarus was involved in aiding refugees to New York who had fledantisemitic pogroms in eastern Europe,and she saw a way to express her empathy for these refugees in terms of the statue.[4]The last lines of the sonnet were set to music byIrving Berlinas the song "Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor" for the 1949 musicalMiss Liberty,which was based on the sculpting of the Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World). The latter part of the sonnet was also set byLee Hoibyin his song "The Lady of the Harbor" written in 1985 as part of his song cycle "Three Women".

Lazarus was also the author ofPoems and Translations(New York, 1867);Admetus, and other Poems(1871);Alide: An Episode of Goethe's Life(Philadelphia, 1874);Poems and Ballads of Heine(New York, 1881);Poems, 2 Vols.;Narrative, Lyric and Dramatic;as well asJewish Poems and Translations.[5]

Early years and education[edit]

Emma Lazarus was born inNew York City,July 22, 1849,[6]into a large Jewish family. She was the fourth of seven children of Moses Lazarus, a wealthy merchant[7]and sugar refiner,[8]and Esther Nathan (of a long-established German-Jewish New York family).[9]One of her great-grandfathers on the Lazarus side was from Germany;[10]the rest of her Lazarus ancestors were originally fromPortugaland they were among theoriginal twenty-three Portuguese Jews who arrived in New Amsterdamafter they fledRecife,Brazilin an attempt to flee from theInquisition.[11][8]Lazarus's great-great-grandmother on her mother's side,Grace Seixas Nathan(born inStratford, Connecticut,in 1752) was also a poet.[12]Lazarus was related through her mother toBenjamin N. Cardozo,Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.Her siblings included sistersJosephine,Sarah, Mary, Agnes and Annie, and a brother, Frank.[13][14][15]

Privately educated by tutors from an early age, she studied American and British literature as well as several languages, includingGerman,French,andItalian.[16]She was attracted in youth to poetry, writing her first lyrics when she was eleven years old.[17]

Career[edit]

Writer[edit]

The first stimulus for Lazarus's writing was offered by theAmerican Civil War.A collection of herPoems and Translations,verses written between the ages of fourteen and seventeen, appeared in 1867 (New York), and was commended byWilliam Cullen Bryant.[9]It included translations fromFriedrich Schiller,Heinrich Heine,Alexandre Dumas,andVictor Hugo.[7][6]Admetus and Other Poemsfollowed in 1871. The title poem was dedicated "To my friendRalph Waldo Emerson",whose works and personality were exercising an abiding influence upon the poet's intellectual growth.[7]During the next decade, in which "Phantasies" and "Epochs" were written, her poems appeared chiefly inLippincott's Monthly MagazineandScribner's Monthly.[9]

By this time, Lazarus's work had won recognition abroad. Her first prose production,Alide: An Episode of Goethe's Life,a romance treating of theFriederike Brionincident, was published in 1874 (Philadelphia), and was followed byThe Spagnoletto(1876), a tragedy.Poems and Ballads of Heinrich Heine(New York, 1881) followed, and was prefixed by a biographical sketch of Heine; Lazarus's renderings of some of Heine's verse are considered among the best in English.[18]In the same year, 1881, she became friends withRose Hawthorne Lathrop.[19]In April 1882, Lazarus published inThe Century Magazinethe article "Was theEarl of Beaconsfielda Representative Jew? "Her statement of the reasons for answering this question in the affirmative may be taken to close what may be termed the Hellenic and journeyman period of Lazarus's life, during which her subjects were drawn from classic and romantic sources.[20]

Lazarus also wroteThe Crowing of the Red Cock,[6]and the sixteen-part cycle poem "Epochs".[21]In addition to writing her own poems, Lazarus edited many adaptations of German poems, notably those ofJohann Wolfgang von Goetheand Heinrich Heine.[22]She also wrote a novel and two plays in five acts,The Spagnoletto,a tragic verse drama aboutthe titular figureandThe Dance to Death,a dramatization of a German short story about the burning of Jews inNordhausenduring theBlack Death.[23]During the time Lazarus became interested in her Jewish roots, she continued her purely literary and critical work in magazines with such articles as "Tommaso Salvini", "Salvini's 'King Lear'","Emerson's Personality "," Heine, the Poet "," A Day in Surrey with William Morris ", and others.[24]

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door! "(1883)

Lines from her sonnet "The New Colossus"appear on a bronze plaque which was placed in the pedestal of theStatue of Libertyin 1903.[2]The sonnet was written in 1883 and donated to an auction, conducted by the "Art Loan Fund Exhibition in Aid of theBartholdiPedestal Fund for the Statue of Liberty "in order to raise funds to build the pedestal.[a][b]Lazarus's close friendRose Hawthorne Lathropwas inspired by "The New Colossus" to found theDominican Sisters of Hawthorne.[26]

She traveled twice to Europe, first in 1883 and again from 1885 to 1887.[27]On one of those trips,Georgiana Burne-Jones,the wife of thePre-RaphaelitepainterEdward Burne-Jones,introduced her toWilliam Morrisat her home.[28] She also met withHenry James,Robert BrowningandThomas Huxleyduring her European travels.[16]A collection ofPoems in Prose(1887) was her last book. HerComplete Poems with a Memoirappeared in 1888, at Boston.[6]

Activism[edit]

Lazarus was a friend and admirer of the American political economistHenry George.She believed deeply inGeorgisteconomic reforms and became active in the "single tax" movement forland value tax.Lazarus published a poem in theNew York Timesnamed after George's book,Progress and Poverty.[29]

Lazarus became more interested in her Jewish ancestry as she heard of the Russianpogromsthat followed theassassination of Tsar Alexander IIin 1881. As a result of thisanti-Semiticviolence, and the poor standard of living in Russia in general, thousands of destitute Ashkenazi Jews emigrated from the RussianPale of Settlementto New York. Lazarus began to advocate on behalf of indigent Jewish immigrants. She helped establish theHebrew Technical Institutein New York to providevocational trainingto assist destitute Jewish immigrants to become self-supporting. Lazarus volunteered as well in theHebrew Emigrant Aid Societyemployment bureau, which she eventually criticized its organization.[30]In 1883, she founded the Society for the Improvement and Colonization of East European Jews.[8]

The literary fruits of identification with her religion were poems like "The Crowing of the Red Cock", "The Banner of the Jew", "The Choice", "The New Ezekiel", "The Dance to Death" (a strong, though unequally executed drama), and her last published work (March 1887), "By the Waters of Babylon: Little Poems in Prose", which constituted her strongest claim to a foremost rank in American literature. During the same period (1882–87), Lazarus translated the Hebrew poets of medieval Spain with the aid of the German versions of Michael Sachs and Abraham Geiger, and wrote articles, signed and unsigned, upon Jewish subjects for the Jewish press, besides essays on "Bar Kochba", "Henry Wadsworth Longfellow", "M. Renan and the Jews", and others for Jewish literary associations.[20]Several of her translations from medieval Hebrew writers found a place in the ritual of American synagogues.[6]Lazarus's most notable series of articles was that titled "An Epistle to the Hebrews" (The American Hebrew,November 10, 1882 – February 24, 1883), in which she discussed the Jewish problems of the day, urged a technical and a Jewish education for Jews, and ranged herself among the advocates of an independent Jewish nationality and of Jewish repatriation in Palestine. The only collection of poems issued during this period wasSongs of a Semite: The Dance to Death and Other Poems(New York, 1882), dedicated to the memory of George Eliot.[24]

Death and legacy[edit]

Lazarus returned to New York City seriously ill after she completed her second trip to Europe, and she died two months later, on November 19, 1887,[5]most likely fromHodgkin's lymphoma.She never married.[31][32]Lazarus was buried inBeth Olam CemeteryinCypress Hills, Brooklyn.The Poems of Emma Lazarus(2 vols., Boston and New York, 1889) was published after her death, comprising most of her poetic work from previous collections, periodical publications, and some of the literary heritage which her executors deemed appropriate to preserve for posterity.[24]Her papers are kept by the American Jewish Historical Society,Center for Jewish History,[33]and her letters are collected atColumbia University.[34]

A stamp featuring the Statue of Liberty and Lazarus's poem "The New Colossus" was issued byAntigua and Barbudain 1985.[35]In 1992, she was named as a Women's History Month Honoree by theNational Women's History Project.[36]Lazarus was honored by the Office of theManhattan Borough Presidentin March 2008, and her home on West10th Streetwas included on a map ofWomen's Rights Historic Sites.[37]In 2009, she was inducted into theNational Women's Hall of Fame.[38]TheMuseum of Jewish Heritagefeatured an exhibition about Lazarus in 2012.

BiographerEsther Schorpraised Lazarus' lasting contribution:

The irony is that the statue goes on speaking, even when the tide turns against immigration — even against immigrants themselves, as they adjust to their American lives. You can't think of the statue without hearing the words Emma Lazarus gave her.[39]

Style and themes[edit]

Lazarus contributed toward shaping the self-image of the United States as well as how the country understands the needs of those who emigrate to the United States. Her themes produced sensitivity and enduring lessons regarding immigrants and their need for dignity.[40]What was needed to make her a poet of the people as well as one of literary merit was a great theme, the establishment of instant communication between some stirring reality and her still hidden and irresolute subjectivity. Such a theme was provided by the immigration of Russian Jews to America, consequent upon the proscriptiveMay Lawsof 1882. She rose to the defense of her ethnic compatriots in powerful articles, as contributions toThe Century(May 1882 and February 1883). Hitherto, her life had held no Jewish inspiration. Though of Sephardic ancestry, and ostensibly Orthodox in belief, her family had till then not participated in the activities of thesynagogueor of the Jewish community. Contact with the unfortunates from Russia led her to study the Torah, the Hebrew language, Judaism, and Jewish history.[20]While her early poetry demonstrated no Jewish themes, herSongs of a Semite(1882) is considered to be the earliest volume of Jewish American poetry.[41]

A review ofAlidebyLippincott's Monthly Magazinewas critical of Lazarus's style and elements of technique.[42]

Notes[edit]

- ^Auction event named as "Lowell says poem gave the statue" a raison d'être'";fell into obscurity; not mentioned at statue opening; Georgina Schuyler's campaign for the plaque.[2]

- ^Solicited by "William Maxwell Evert" [sic; presumablyWilliam Maxwell Evarts] Lazarus refused initially; convinced byConstance Cary Harrison[25]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Cavitch, Max (February 1, 2006)."Emma Lazarus and the Golem of Liberty".American Literary History.18(1): 1–28.RetrievedJanuary 12,2018.

- ^abcYoung 1997,p. 3.

- ^Watts 2014,p. 123.

- ^Khan 2010,pp. 165–166.

- ^abSladen & Roberts 1891,p. 434.

- ^abcdeGilman, Peck & Colby 1907,p. 39.

- ^abcD. Appleton & Company 1887,p. 414.

- ^abcGoodwin 2015,p. 370.

- ^abcSinger & Adler 1906,p. 650.

- ^"Four Founders: Emma Lazarus".Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^Appel, Phyllis (January 21, 2013).The Jewish Connection.Graystone Enterprises LLC.ISBN9781301060931.RetrievedJanuary 7,2019.

- ^Schor 2008,p. 1.

- ^Wheeler 1889,p. 176.

- ^Schor 2017,pp. 8, 226.

- ^Weinrib, Henry."Emma Lazarus".www.jewishmag.com.Jewish Magazine.RetrievedJanuary 12,2018.

- ^abWalker 1992,p. 332.

- ^Lazarus & Eiselein 2002,p. 15.

- ^World's Congress of Religions 1893,p. 976.

- ^Young 1997,p. 186.

- ^abcSinger & Adler 1906,p. 651.

- ^"The Poems of Emma Lazarusin Two Volumes ".Century Magazine.ASINB0082RVVJ2.

- ^The Poems of Emma Lazarusin Two Volumes, Kindle ebooksASINB0082RVVJ2andASINB0082RDHSA.

- ^Parini 2003,p. 1.

- ^abcSinger & Adler 1906,p. 652.

- ^Felder & Rosen 2005,p. 45.

- ^"Exhibit highlights connection between Jewish poet, Catholic nun".The Tidings.Archdiocese of Los Angeles.Catholic News Service.September 17, 2010. p. 16. Archived fromthe originalon September 21, 2010.RetrievedSeptember 20,2010.

- ^Schor 2006,p. 1.

- ^Flanders 2001,p. 186.

- ^"Progress and Poverty".The New York Times.October 2, 1881. p. 3.RetrievedMay 21,2013.

- ^Esther Schor,Emma Lazarus(2008), Random House (Jewish Encounters series),ISBN0805242759.p. 148et. seq.;quotation from Lazarus is on p. 149-150.

- ^Hewitt 2011,p. 55.

- ^Snodgrass 2014,p. 321.

- ^"Guide to the Emma Lazarus, papers".Center for Jewish History.RetrievedJanuary 12,2018.

- ^Young 1997,p. 221.

- ^Eisenberg 2002,p. 52.

- ^"Past Women's History Month Honorees".National Women's History Project.Archived fromthe originalon June 3, 2017.RetrievedAugust 3,2017.

- ^"Manhattan Borough President – Home".Archived fromthe originalon July 18, 2011.

- ^"Lazarus, Emma".National Women's Hall of Fame.RetrievedNovember 1,2016.

- ^"Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor, Your Poet".The Attic.September 13, 2019.RetrievedNovember 5,2019.

- ^Moore 2005,p. xvi.

- ^Gitenstein 2012,p. 3.

- ^Vogel 1980,p. 103.

Attribution[edit]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:D. Appleton & Company (1887).Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events(Public domain ed.). D. Appleton & Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:D. Appleton & Company (1887).Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events(Public domain ed.). D. Appleton & Company. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Gilman, Daniel Coit; Peck, Harry Thurston; Colby, Frank Moore (1907).The new international encyclopædia(Public domain ed.). Dodd, Mead and company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Gilman, Daniel Coit; Peck, Harry Thurston; Colby, Frank Moore (1907).The new international encyclopædia(Public domain ed.). Dodd, Mead and company. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus (1906).The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day.Vol. 7 (Public domain ed.). Funk & Wagnalls Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus (1906).The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day.Vol. 7 (Public domain ed.). Funk & Wagnalls Company. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Sladen, Douglas Brooke Wheelton; Roberts, Goodridge Bliss (1891).Younger American Poets, 1830–1890(Public domain ed.). Griffith, Farran, Okeden & Welsh. p.434.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Sladen, Douglas Brooke Wheelton; Roberts, Goodridge Bliss (1891).Younger American Poets, 1830–1890(Public domain ed.). Griffith, Farran, Okeden & Welsh. p.434. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Wheeler, Edward Jewitt (1889).Current Opinion.Vol. 2 (Public domain ed.). Current Literature Publishing Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Wheeler, Edward Jewitt (1889).Current Opinion.Vol. 2 (Public domain ed.). Current Literature Publishing Company. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:World's Congress of Religions (1893).The Addresses and Papers Delivered Before the Parliament, and an Abstract of the Congresses: Held in the Art Institute, Chicago, Ill., Aug. 25 to Oct. 15, 1893(Public domain ed.). Conkey.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:World's Congress of Religions (1893).The Addresses and Papers Delivered Before the Parliament, and an Abstract of the Congresses: Held in the Art Institute, Chicago, Ill., Aug. 25 to Oct. 15, 1893(Public domain ed.). Conkey.

Bibliography[edit]

- Beilin, Israel Ber. Dos lebn fun Ema Lazarus a biografye. 1946. Nyu-Yorḳ: Yidishn fraṭernaln folḳs-ordn

- Cavitch, Max. (2008)."Emma Lazarus and the Golem of Liberty."The Traffic in Poems: Nineteenth-Century Poetry and Transatlantic Exchange.Ed. Meredith McGill. Rutgers University Press. 97–122.ISBN978-0813542300.

- Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2002).The Jewish World in Stamps: 4000 Years of Jewish Civilization in Postal Stamps.Schreiber Publishing.ISBN978-1-887563-76-5.

- Felder, Deborah G.; Rosen, Diana (2005).Fifty Jewish Women Who Changed The World.Kensington Publishing Corporation.ISBN978-0-8065-2656-0.

- Flanders, Judith (2001).A Circle of Sisters: Alice Kipling, Georgiana Burne-Jones, Agnes Poynter and Louisa Baldwin.W.W. Norton & Company.ISBN978-0-393-05210-7.

- Gitenstein, R. Barbara (February 2012).Apocalyptic Messianism and Contemporary Jewish-American Poetry.SUNY Press.ISBN978-1-4384-0415-8.

- Goodwin, Neva (July 17, 2015).Encyclopedia of Women in American History.Routledge.ISBN978-1-317-47162-2.

- Hewitt, S. R. (December 16, 2011).Jewish Treats: 99 Fascinating Jewish Personalities.BookBaby.ISBN978-1-61842-866-0.[permanent dead link]

- Khan, Yasmin Sabina (2010).Enlightening the World: The Creation of the Statue of Liberty.Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.ISBN978-0-8014-4851-5.

- Moore, Hannia S. (January 1, 2005).Liberty's Poet: Emma Lazarus.TurnKey Press.ISBN978-0-9754803-4-2.

- Lazarus, Emma; Eiselein, Gregory (June 4, 2002).Emma Lazarus: Selected Poems and Other Writings.Broadview Press.ISBN978-1-55111-285-5.

- Parini, Jay (October 2003).The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-515653-9.

- Schor, Esther H. (September 5, 2006).Emma Lazarus.Nextbook.ISBN9780805242164.

- Schor, Esther (October 21, 2008).Emma Lazarus.Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.ISBN978-0-8052-4275-1.

- Schor, Esther (April 25, 2017).Emma Lazarus.Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.ISBN978-0-8052-1166-5.

- Vogel, Dan (1980).Emma Lazarus.Thomson Gale.ISBN978-0-8057-7233-3.

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (May 14, 2014).Encyclopedia of Feminist Literature.Infobase Publishing.ISBN978-1-4381-0910-7.

- Walker, Cheryl (1992).American Women Poets of the Nineteenth Century: An Anthology.Rutgers University Press. p.332.ISBN978-0-8135-1791-9.

- Watts, Emily Stipes (September 10, 2014).The Poetry of American Women from 1632 to 1945.University of Texas Press.ISBN978-1-4773-0344-3.

- Young, Bette Roth (August 1, 1997).Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters.Jewish Publication Society.ISBN978-0-8276-0618-0.

External links[edit]

- Works by Emma LazarusatProject Gutenberg

- Works by or about Emma LazarusatInternet Archive

- Works by Emma LazarusatLibriVox(public domain audiobooks)

- Jewish Virtual Library: Emma Lazarus

- Jewish Women's Archive: HISTORY MAKERS: Emma Lazarus, 1849–1887

- Finding aid to Emma Lazarus, 1868–1929, at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- National Public Radio: "Emma Lazarus, Poet of the Huddled Masses"

- Jewish-American Hall of Fame: Virtual Tour: Emma Lazarus (1849–1887)

- Dr. David P. Stern: Welcome to my World: Emma Lazarusat theWayback Machine(archived June 16, 2006)

- "Who Was Emma Lazarus?"by Dr. HenryHenry Abramson

- Emma LazarusatFind a Grave

- 1849 births

- 1887 deaths

- 19th-century American poets

- 19th-century American women writers

- Activists from New York City

- American feminist writers

- American people of German-Jewish descent

- American people of Portuguese-Jewish descent

- American women poets

- Burials at Beth Olom Cemetery

- Georgists

- Jewish American activists

- Jewish American poets

- Jewish feminists

- Jewish women writers

- Statue of Liberty

- Poets from New York City

- Deaths from lymphoma in New York (state)

- Deaths from Hodgkin lymphoma

- 19th-century American Sephardic Jews

- American people of Portuguese descent