Etruscan civilization

Etruscans 𐌓𐌀𐌔𐌄𐌍𐌍𐌀 Rasenna | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 900 BC[1]–27 BC[1] | |||||||||

Extent of Etruscan civilization and the twelve Etruscan League cities. | |||||||||

| Status | City-states | ||||||||

| Common languages | Etruscan | ||||||||

| Religion | Etruscan | ||||||||

| Government | Chiefdom | ||||||||

| Legislature | Etruscan League | ||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age,Ancient history | ||||||||

| 900 BC[1] | |||||||||

• Last Etruscan cities formally absorbed by Rome | 27 BC[1] | ||||||||

| Currency | Etruscan coinage(5th century BC onward) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

TheEtruscan civilization(/ɪˈtrʌskən/ih-TRUS-kən) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabitedEtruriainancient Italy,with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states.[2]After conquering adjacent lands, itsterritorycovered, at its greatest extent, roughly what is nowTuscany,westernUmbria,and northernLazio,[3][4]as well as what are now thePo Valley,Emilia-Romagna,south-easternLombardy,southernVeneto,and westernCampania.[5][6]

On the origins of the Etruscans a large body of literature has flourished; however, the consensus among modern scholars is that the Etruscans were an indigenous population.[7][8][9][10][11]The earliest evidence of aculturethat is identifiably Etruscan dates from about 900BC.[1]This is the period of theIron AgeVillanovan culture,considered to be the earliest phase of Etruscan civilization,[12][13][14][15][16]which itself developed from the previous lateBronze AgeProto-Villanovan culturein the same region,[17]part of the central EuropeanUrnfield culturesystem. Etruscan civilization dominated Italy until it fell to the expandingRomebeginning in the late 4thcenturyBC as a result of theRoman–Etruscan Wars;[18]Etruscans were grantedRoman citizenshipin 90 BC, and only in 27 BC the whole Etruscan territory was incorporated into the newly establishedRoman Empire.[1]

The territorial extent of Etruscan civilization reached its maximum around 750 BC, during the foundational period of theRoman Kingdom.Its culture flourished in three confederacies of cities: that ofEtruria(Tuscany, Latium and Umbria), that of thePo Valleywith the easternAlps,and that ofCampania.[19][20]The league in northern Italy is mentioned inLivy.[21][22][23]The reduction in Etruscan territory was gradual, but after 500BC, the political balance of power on the Italian peninsula shifted away from the Etruscans in favor of the risingRoman Republic.[24]

The earliest known examples of Etruscan writing are inscriptions found insouthern Etruriathat date to around 700BC.[18][25]The Etruscans developed a system of writing derived from theEuboean alphabet,which was used in theMagna Graecia(coastal areas located inSouthern Italy).[26]TheEtruscan languageremains only partly understood, making modern understanding of their society and culture heavily dependent on much later and generally disapproving Roman and Greek sources. In the Etruscanpolitical system,authority resided in its individual small cities, and probably in its prominent individual families. At the height of Etruscan power, elite Etruscan families grew very rich through trade with theCeltic worldto the north and the Greeks to the south, and they filled their large family tombs with imported luxuries.[27][28]

Legend and history[edit]

Ethnonym and etymology[edit]

Etruscan: Tular Rasnal

English: Boundary of the People

According toDionysiusthe Etruscans called themselvesRasenna(GreekῬασέννα), a stem from the Etruscan Rasna (𐌛𐌀𐌔𐌍𐌀), the people. Evidence of inscriptions as Tular Rasnal (𐌕𐌖𐌋𐌀𐌛 𐌛𐌀𐌔𐌍𐌀𐌋), "boundary of the people", or Mechlum Rasnal (𐌌𐌄𐌙𐌋 𐌛𐌀𐌔𐌍𐌀𐌋). "community of the people", attest to its autonym usage. TheTyrsenianetymology however remains unknown.[29][30][31]

InAttic Greek,the Etruscans were known asTyrrhenians(Τυρρηνοί,Tyrrhēnoi,earlierΤυρσηνοίTyrsēnoi),[32]from which the Romans derived the namesTyrrhēnī,Tyrrhēnia(Etruria),[33]andMare Tyrrhēnum(Tyrrhenian Sea).[34]

The ancient Romans referred to the Etruscans as theTuscīorEtruscī(singularTuscus).[35][36][37]Their Roman name is the origin of the terms "Toscana",which refers to their heartland, and"Etruria",which can refer to their wider region. The termTusciis thought by linguists to have been the Umbrian word for "Etruscan", based on an inscription on anancient bronze tabletfrom a nearby region.[38]The inscription contains the phraseturskum... nomen,literally "the Tuscan name". Based on a knowledge of Umbrian grammar, linguists can infer that the base form of the word turskum is *Tursci,[39]which would, throughmetathesisand a word-initialepenthesis,be likely to lead to the form,E-trus-ci.[40]

As for the original meaning of the root, *Turs-, a widely cited hypothesis is that it, like the word Latinturris,means "tower", and comes from the ancient Greek word for tower:τύρσις,[41][42]likely a loan into Greek. On this hypothesis, the Tusci were called the "people who build towers"[41]or "the tower builders".[43]This proposed etymology is made the more plausible because the Etruscans preferred to build their towns on high precipices reinforced by walls. Alternatively,GiulianoandLarissa Bonfantehave speculated that Etruscan houses may have seemed like towers to the simple Latins.[44]The proposed etymology has a long history,Dionysius of Halicarnassushaving observed in the first century B. C., "[T]here is no reason that the Greeks should not have called [the Etruscans] by this name, both from their living in towers and from the name of one of their rulers."[45]In his recentEtymological Dictionary of Greek,Robert Beekes claims the Greek word is a "loanword from a Mediterranean language", a hypothesis that goes back to an article byPaul KretschmerinGlottafrom 1934.[46][47]

Origins[edit]

Ancient sources[edit]

Literary and historical texts in the Etruscan language have not survived, and the language itself is only partially understood by modern scholars. This makes modern understanding of their society and culture heavily dependent on much later and generally disapproving Roman and Greek sources. These ancient writers differed in their theories about the origin of the Etruscan people. Some suggested they werePelasgianswho had migrated there from Greece. Others maintained that they were indigenous to central Italy and were not from Greece.

The first Greek author to mention the Etruscans, whom the Ancient Greeks calledTyrrhenians,was the 8th-century BC poetHesiod,in his work, theTheogony.He mentioned them as residing in central Italy alongside the Latins.[49]The 7th-century BCHomeric Hymnto Dionysus[50]referred to them as pirates.[51]Unlike later Greek authors, these authors did not suggest that Etruscans had migrated to Italy from the east, and did not associate them with the Pelasgians.

It was only in the 5th century BC, when the Etruscan civilization had been established for several centuries, that Greek writers started associating the name "Tyrrhenians" with the "Pelasgians", and even then, some did so in a way that suggests they were meant only as generic, descriptive labels for "non-Greek" and "indigenous ancestors of Greeks", respectively.[52]The 5th-century BC historiansHerodotus,[53]andThucydides[54]and the 1st-century BC historianStrabo,[55]did seem to suggest that the Tyrrhenians were originally Pelasgians who migrated to Italy fromLydiaby way of the Greek island ofLemnos.They all described Lemnos as having been settled by Pelasgians, whom Thucydides identified as "belonging to the Tyrrhenians" (τὸ δὲ πλεῖστον Πελασγικόν, τῶν καὶ Λῆμνόν ποτε καὶ Ἀθήνας Τυρσηνῶν). As Strabo and Herodotus told it,[56]the migration to Lemnos was led byTyrrhenus/ Tyrsenos, the son ofAtys(who was king of Lydia). Strabo[55]added that the Pelasgians of Lemnos andImbrosthen followed Tyrrhenus to theItalian Peninsula.According to the logographerHellanicus of Lesbos,there was a Pelasgian migration fromThessalyinGreeceto the Italian peninsula, as part of which the Pelasgians colonized the area he called Tyrrhenia, and they then came to be called Tyrrhenians.[57]

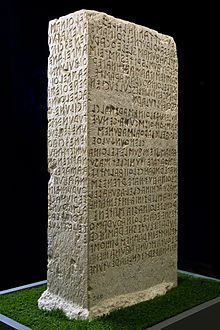

There is some evidence suggesting a link between the island of Lemnos and the Tyrrhenians. TheLemnos Stelebears inscriptions in a language with strong structural resemblances to the language of the Etruscans.[58]The discovery of these inscriptions in modern times has led to the suggestion of a "Tyrrhenian language group"comprising Etruscan, Lemnian, and theRaeticspoken in theAlps.

However, the 1st-century BC historianDionysius of Halicarnassus,a Greek living in Rome, dismissed many of the ancient theories of other Greek historians and postulated that the Etruscans were indigenous people who had always lived in Etruria and were different from both the Pelasgians and the Lydians.[59]Dionysius noted that the 5th-century historianXanthus of Lydia,who was originally fromSardisand was regarded as an important source and authority for the history of Lydia, never suggested a Lydian origin of the Etruscans and never named Tyrrhenus as a ruler of the Lydians.[59]

For this reason, therefore, I am persuaded that the Pelasgians are a different people from the Tyrrhenians. And I do not believe, either, that the Tyrrhenians were a colony of the Lydians; for they do not use the same language as the latter, nor can it be alleged that, though they no longer speak a similar tongue, they still retain some other indications of their mother country. For they neither worship the same gods as the Lydians nor make use of similar laws or institutions, but in these very respects they differ more from the Lydians than from the Pelasgians. Indeed, those probably come nearest to the truth who declare that the nation migrated from nowhere else, but was native to the country, since it is found to be a very ancient nation and to agree with no other either in its language or in its manner of living.

The credibility of Dionysius of Halicarnassus is arguably bolstered by the fact that he was the first ancient writer to report theendonymof the Etruscans: Rasenna.

The Romans, however, give them other names: from the country they once inhabited, named Etruria, they call them Etruscans, and from their knowledge of the ceremonies relating to divine worship, in which they excel others, they now call them, rather inaccurately, Tusci, but formerly, with the same accuracy as the Greeks, they called them Thyrscoï [an earlier form of Tusci]. Their own name for themselves, however, is the same as that of one of their leaders, Rasenna.

Similarly, the 1st-century BC historianLivy,in hisAb Urbe Condita Libri,said that the Rhaetians were Etruscans who had been driven into the mountains by the invading Gauls; and he asserted that the inhabitants of Raetia were of Etruscan origin.[60]

The Alpine tribes have also, no doubt, the same origin (of the Etruscans), especially the Raetians; who have been rendered so savage by the very nature of the country as to retain nothing of their ancient character save the sound of their speech, and even that is corrupted.

The first-century historianPliny the Elderalso put the Etruscans in the context of theRhaetian peopleto the north, and wrote in hisNatural History(AD 79):[61]

Adjoining these the (Alpine)Noricansare the Raeti andVindelici.All are divided into a number of states. The Raeti are believed to be people of Tuscan race driven out by theGauls,their leader was named Raetus.

Archeological evidence and modern etruscology[edit]

The question of the origins of the Etruscans has long been a subject of interest and debate among historians. In modern times, all the evidence gathered so far by prehistoric and protohistoric archaeologists, anthropologists, and etruscologists points to an autochthonous origin of the Etruscans.[7][8][9][10][11]There is no archaeological or linguistic evidence of a migration of the Lydians or Pelasgians into Etruria.[62][9][8][10][11]Modernetruscologistsand archeologists, such asMassimo Pallottino(1947), have shown that early historians' assumptions and assertions on the subject were groundless.[63]In 2000, the etruscologistDominique Briquelexplained in detail why he believes that ancient Greek historians' accounts on Etruscan origins should not even count as historical documents.[64]He argues that the ancient story of the Etruscans' 'Lydian origins' was a deliberate, politically motivated fabrication, and that ancient Greeks inferred a connection between the Tyrrhenians and the Pelasgians solely on the basis of certain Greek and local traditions and on the mere fact that there had been trade between the Etruscans and Greeks.[65][66]He noted that, even if these stories include historical facts suggesting contact, such contact is more plausibly traceable to cultural exchange than to migration.[67]

Several archaeologists specializing inPrehistoryandProtohistory,who have analyzed Bronze Age and Iron Age remains that were excavated in the territory of historical Etruria have pointed out that no evidence has been found, related either tomaterial cultureor tosocial practices,that can support a migration theory.[68]The most marked and radical change that has been archaeologically attested in the area is the adoption, starting in about the 12th century BC, of the funeral rite of incineration in terracotta urns, which is a Continental European practice, derived from theUrnfield culture;there is nothing about it that suggests an ethnic contribution fromAsia Minoror theNear East.[68]

A 2012 survey of the previous 30 years' archaeological findings, based on excavations of the major Etruscan cities, showed a continuity of culture from the last phase of the Bronze Age (13th–11th century BC) to the Iron Age (10th–9th century BC). This is evidence that the Etruscan civilization, which emerged around 900 BC, was built by people whose ancestors had inhabited that region for at least the previous 200 years.[69]Based on this cultural continuity, there is now a consensus among archeologists that Proto-Etruscan culture developed, during the last phase of the Bronze Age, from the indigenousProto-Villanovan culture,and that the subsequent Iron AgeVillanovan cultureis most accurately described as an early phase of the Etruscan civilization.[17]It is possible that there were contacts between northern-central Italy and theMycenaean worldat the end of the Bronze Age. However contacts between the inhabitants of Etruria and inhabitants ofGreece,Aegean SeaIslands, Asia Minor, and the Near East are attested only centuries later, when Etruscan civilization was already flourishing and Etruscanethnogenesiswas well established. The first of these attested contacts relate to theGreek colonies in Southern ItalyandPhoenician-Puniccolonies inSardinia,and the consequentorientalizing period.[70]

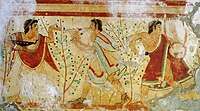

One of the most common mistakes for a long time, even among some scholars of the past, has been to associate the laterOrientalizing periodof Etruscan civilization with the question of its origins. Orientalization was an artistic and cultural phenomenon that spread among the Greeks themselves, and throughout much of the central and western Mediterranean, not only in Etruria.[71]Orientalizing period in the Etruscans was due, as has been amply demonstrated by archeologists, to contacts with the Greeks and the Eastern Mediterranean and not to mass migrations.[72]The facial features (the profile, almond-shaped eyes, large nose) in the frescoes and sculptures, and the depiction of reddish-brown men and light-skinned women, influenced by archaic Greek art, followed the artistic traditions from the Eastern Mediterranean, that had spread even among the Greeks themselves, and to a lesser extent also to other several civilizations in the central and western Mediterranean up to theIberian Peninsula.Actually, many of the tombs of the Late Orientalizing and Archaic periods, such as theTomb of the Augurs,theTomb of the Tricliniumor theTomb of the Leopards,as well as other tombs from the archaic period in theMonterozzi necropolisinTarquinia,were painted by Greek painters or, in any case, foreigner artists. These images have, therefore, a very limited value for a realistic representation of the Etruscan population.[73]It was only from the end of the 4th century BC that evidence of physiognomic portraits began to be found in Etruscan art and Etruscan portraiture became more realistic.[74]

Genetic research[edit]

There have been numerous biological studies on the Etruscan origins, the oldest of which dates back to the 1950s when research was still based on blood tests of modern samples, and DNA analysis (including the analysis of ancient samples) was not yet possible.[75][76][77]It is only in very recent years, with the development ofarchaeogenetics,that comprehensive studies containing thewhole genome sequencingof Etruscan samples have been published, includingautosomal DNAandY-DNA,autosomal DNA being the "most valuable to understand what really happened in an individual's history", as stated by geneticistDavid Reich,whereas previously studies were based only onmitochondrial DNAanalysis, which contains less and limited information.[78]

An archeogenetic study focusing on the question of Etruscan origins was published in September 2021 in the journalScience Advancesand analyzed theautosomal DNAand the uniparental markers (Y-DNA and mtDNA) of 48 Iron Age individuals fromTuscanyandLazio,spanning from 800 to 1 BC, and concluding that the Etruscans were autochthonous (locally indigenous), and they had a genetic profile similar to their Latin neighbors. In the Etruscan individuals the ancestral componentSteppewas present in the same percentages found in the previously analyzed Iron Age Latins, and in the Etruscan DNA was completely absent a signal of recent admixture with Anatolia and the Eastern Mediterranean. Both Etruscans and Latins joined firmly the European cluster, west of modern Italians. The Etruscans were a mixture of WHG, EEF, and Steppe ancestry; 75% of the Etruscan male individuals were found to belong tohaplogroup R1b (R1b M269),especially its cladeR1b-P312and its derivativeR1b-L2,whose direct ancestor isR1b-U152,while the most common mitochondrial DNA haplogroup among the Etruscans wasH.[79]

The conclusions of the 2021 study are in line with a 2019 study previously published in the journalSciencethat analyzed the remains of elevenIron Ageindividuals from the areas around Rome, of which four were Etruscan individuals, one buried inVeio Grotta Gramicciafrom the Villanovan era (900-800 BC) and three buried in La Mattonara Necropolis nearCivitavecchiafrom the Orientalizing period (700-600 BC). The study concluded that Etruscans (900–600 BC) and theLatins(900–500 BC) fromLatium vetuswere genetically similar,[80]with genetic differences between the examined Etruscans and Latins found to be insignificant.[81]The Etruscan individuals and contemporary Latins were distinguished from preceding populations of Italy by the presence ofc. 30%steppe ancestry.[82]Their DNA was a mixture of two-thirdsCopper Ageancestry (EEF+WHG;Etruscans ~66–72%, Latins ~62–75%), and one-thirdSteppe-related ancestry(Etruscans ~27–33%, Latins ~24–37%).[80]The only sample ofY-DNAextracted belonged tohaplogroup J-M12 (J2b-L283),found in an individual dated 700-600 BC, and carried exactly the M314 derived allele also found in a Middle Bronze Age individual fromCroatia(1631–1531 BC). While the four samples ofmtDNAextracted belonged to haplogroupsU5a1,H,T2b32,K1a4.[83]

Among the older studies, only based on mitochondrial DNA, a mtDNA study, published in 2018 in the journalAmerican Journal of Physical Anthropology,compared both ancient and modern samples from Tuscany, from thePrehistory,Etruscan age,Roman age,Renaissance,and Present-day, and concluded that the Etruscans appear as a local population, intermediate between the prehistoric and the other samples, placing in the temporal network between theEneolithic Ageand the Roman Age.[84]

A couple ofmitochondrial DNAstudies, published in 2013 in the journalsPLOS OneandAmerican Journal of Physical Anthropology,based on Etruscan samples from Tuscany and Latium, concluded that the Etruscans were an indigenous population, showing that Etruscan mtDNA appears to fall very close to a Neolithic population fromCentral Europe(Germany,Austria,Hungary) and to other Tuscan populations, strongly suggesting that the Etruscan civilization developed locally from theVillanovan culture,as already supported by archaeological evidence and anthropological research,[17][85]and that genetic links between Tuscany and westernAnatoliadate back to at least 5,000 years ago during theNeolithicand the "most likely separation time between Tuscany and Western Anatolia falls around 7,600 years ago", at the time of the migrations ofEarly European Farmers(EEF) from Anatolia to Europe in the early Neolithic. The ancient Etruscan samples had mitochondrial DNA haplogroups (mtDNA)JT(subclades ofJandT) andU5,with a minority ofmtDNA H1b.[86][87]

An earlier mtDNA study published in 2004, based on about 28 samples of individuals, who lived from 600 to 100 BC, inVeneto,Etruria, and Campania, stated that the Etruscans had no significant heterogeneity, and that all mitochondrial lineages observed among the Etruscan samples appear typically European orWest Asian,but only a fewhaplotypeswere shared with modern populations. Allele sharing between the Etruscans and modern populations is highest amongGermans(seven haplotypes in common), theCornishfrom the South West of Britain (five haplotypes in common), theTurks(four haplotypes in common), and theTuscans(two haplotypes in common).[88]While, the modern populations with the shortest genetic distance from the ancient Etruscans, based solely on mtDNA and FST, wereTuscansfollowed by the Turks, other populations from the Mediterranean and the Cornish after.[88]This study was much criticized by other geneticists, because "data represent severely damaged or partly contaminated mtDNA sequences" and "any comparison with modern population data must be considered quite hazardous",[89][90][91]and archaeologists, who argued that the study was not clear-cut and had not provided evidence that the Etruscans were an intrusive population to the European context.[77][76]

In the collective volumeEtruscologypublished in 2017, British archeologist Phil Perkins, echoing an earlier article of his from 2009, provides an analysis of the state of DNA studies and writes that "none of the DNA studies to date conclusively prove that [the] Etruscans were an intrusive population in Italy that originated in the Eastern Mediterranean or Anatolia" and "there are indications that the evidence of DNA can support the theory that Etruscan people are autochthonous in central Italy".[76][77]

In his 2021 book,A Short History of Humanity,German geneticistJohannes Krause,co-director of theMax Planck Institute for Evolutionary AnthropologyinJena,concludes that it is likely that theEtruscan language(as well asBasque,Paleo-Sardinian,andMinoan) "developed on the continent in the course of theNeolithic Revolution".[92]

Periodization of Etruscan civilization[edit]

The Etruscan civilization begins with the early Iron AgeVillanovan culture,regarded as the oldest phase, that occupied a large area of northern and central Italy during the Iron Age.[12][13][14][15][16]The Etruscans themselves dated the origin of the Etruscan nation to a date corresponding to the 11th or 10th century BC.[13][93]The Villanovan culture emerges with the phenomenon of regionalization from the late Bronze Age culture called "Proto-Villanovan",part of the central EuropeanUrnfield culture system.In the last Villanovan phase, called the recent phase (about 770–730 BC), the Etruscans established relations of a certain consistency with the firstGreek immigrants in southern Italy(inPithecusaand then inCuma), so much so as to initially absorb techniques and figurative models and soon more properly cultural models, with the introduction, for example, of writing, of a new way of banqueting, of a heroic funerary ideology, that is, a new aristocratic way of life, such as to profoundly change the physiognomy of Etruscan society.[93]Thus, thanks to the growing number of contacts with the Greeks, the Etruscans entered what is called theOrientalizing phase.In this phase, there was a heavy influence in Greece, most of Italy and some areas of Spain, from the most advanced areas of theeastern Mediterraneanand theancient Near East.[94]Also directly Phoenician, or otherwise Near Eastern, craftsmen, merchants and artists contributed to the spread in southern Europe of Near Eastern cultural and artistic motifs. The last three phases of Etruscan civilization are called, respectively, Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic, which roughly correspond to the homonymous phases of the ancient Greek civilization.

Chronology[edit]

| Etruscan civilization (900–27 BC)[1] |

Villanovan period (900–720 BC) |

Villanovan I | 900–800 BC |

| Villanovan II | 800–720 BC | ||

| Villanovan III (Bologna area) | 720–680 BC[95] | ||

| Villanovan IV (Bologna area) | 680–540 BC[95] | ||

| Orientalizing period (720–580 BC) |

Early Orientalizing | 720–680 BC | |

| Middle Orientalizing | 680–625 BC | ||

| Late Orientalizing | 625–580 BC | ||

| Archaic period (580–480 BC) |

Archaic | 580–480 BC | |

| Classical period (480–320 BC) |

Classical | 480–320 BC | |

| Hellenistic period (320–27 BC) |

Hellenistic | 320–27 BC |

Expansion[edit]

Etruscan expansion was focused both to the north beyond theApennine Mountainsand into Campania. Some small towns in the sixth century BC disappeared during this time, ostensibly subsumed by greater, more powerful neighbors. However, it is certain that the political structure of the Etruscan culture was similar to, albeit more aristocratic than,Magna Graeciain the south. The mining and commerce of metal, especiallycopperandiron,led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the westernMediterranean Sea.Here, their interests collided with those of the Greeks, especially in the sixth century BC, whenPhocaeansof Italy founded colonies along the coast ofSardinia,SpainandCorsica.This led the Etruscans to ally themselves withCarthage,whose interests also collided with the Greeks.[96][97]

Around 540 BC, theBattle of Alalialed to a new distribution of power in the western Mediterranean. Though the battle had no clear winner,Carthagemanaged to expand its sphere of influence at the expense of the Greeks, and Etruria saw itself relegated to the northernTyrrhenian Seawith full ownership ofCorsica.From the first half of the 5th century BC, the new political situation meant the beginning of the Etruscan decline after losing their southern provinces. In 480 BC, Etruria's ally Carthage was defeated by a coalition of Magna Graecia cities led bySyracuse, Sicily.A few years later, in 474 BC, Syracuse's tyrantHierodefeated the Etruscans at theBattle of Cumae.Etruria's influence over the cities ofLatiumand Campania weakened, and the area was taken over by Romans andSamnites.

In the 4th century BC, Etruria saw aGallicinvasion end its influence over thePo Valleyand theAdriatic coast.Meanwhile,Romehad started annexing Etruscan cities. This led to the loss of the northern Etruscan provinces. During theRoman–Etruscan Wars,Etruria was conquered by Rome in the 3rd century BC.[96][97]

Etruscan League[edit]

According to legend,[98]there was a period between 600 BC and 500 BC in which analliancewas formed among twelve Etruscan settlements, known today as theEtruscan League,Etruscan Federation,orDodecapolis(Greek:Δωδεκάπολις). According to a legend, the Etruscan League of twelve cities was founded byTarchonand his brotherTyrrhenus.Tarchon lent his name to the city ofTarchna,or Tarquinnii, as it was known by the Romans. Tyrrhenus gave his name to theTyrrhenians,the alternative name for the Etruscans. Although there is no consensus on which cities were in the league, the following list may be close to the mark:Arretium,Caisra,Clevsin,Curtun,Perusna,Pupluna,Veii,Tarchna,Vetluna,Volterra,Velzna,andVelch.Some modern authors includeRusellae.[99]The league was mostly an economic and religious league, or a loose confederation, similar to the Greek states. During the laterimperialtimes, when Etruria was just one of many regions controlled by Rome, the number of cities in the league increased by three. This is noted on many later grave stones from the 2nd century BC onwards. According toLivy,the twelvecity-statesmet once a year at theFanum VoltumnaeatVolsinii,where a leader was chosen to represent the league.[100]

There were two other Etruscan leagues ( "Lega dei popoli"): that ofCampania,the main city of which wasCapua,and thePo Valleycity-states in northern Italy, which includedBologna,SpinaandAdria.[100]

Possible founding of Rome[edit]

Those who subscribe to aLatinfoundation of Rome followed by an Etruscan invasion typically speak of an Etruscan "influence" on Roman culture – that is, cultural objects which were adopted by Rome from neighboring Etruria. The prevailing view is that Rome was founded by Latins who later merged with Etruscans. In this interpretation, Etruscan cultural objects are considered influences rather than part of a heritage.[101]Rome was probably a small settlement until the arrival of the Etruscans, who constructed the first elements of its urban infrastructure such as the drainage system.[102][103]

The main criterion for deciding whether an object originated at Rome and traveled by influence to the Etruscans, or descended to the Romans from the Etruscans, is date. Many, if not most, of the Etruscan cities were older than Rome. If one finds that a given feature was there first, it cannot have originated at Rome. A second criterion is the opinion of the ancient sources. These would indicate that certain institutions and customs came directly from the Etruscans. Rome is located on the edge of what was Etruscan territory. When Etruscan settlements turned up south of the border, it was presumed that the Etruscans spread there after the foundation of Rome, but the settlements are now known to have preceded Rome.

Etruscan settlements were frequently built on hills – the steeper the better – and surrounded by thick walls. According toRoman mythology,whenRomulus and Remusfounded Rome, they did so on thePalatine Hillaccording to Etruscan ritual; that is, they began with apomeriumor sacred ditch. Then, they proceeded to the walls. Romulus was required to kill Remus when the latter jumped over the wall, breaking its magic spell (see also underPons Sublicius). The name of Rome is attested in Etruscan in the formRuma-χmeaning 'Roman', a form that mirrors other attested ethnonyms in that language with the same suffix-χ:Velzna-χ'(someone) from Volsinii' andSveama-χ'(someone) fromSovana'. This in itself, however, is not enough to prove Etruscan origin conclusively. If Tiberius is fromθefarie,then Ruma would have been placed on theThefar(Tiber) river. A heavily discussed topic among scholars is who was the founding population of Rome. In 390 BC, thecity of Rome was attackedby theGauls,and as a result may have lost many – though not all – of its earlier records.

Later history relates that some Etruscans lived in theVicus Tuscus,[104]the "Etruscan quarter", and that there was an Etruscan line of kings (albeit ones descended from a Greek,Demaratus of Corinth) that succeeded kings of Latin and Sabine origin. Etruscophile historians would argue that this, together with evidence for institutions, religious elements and other cultural elements, proves that Rome was founded by Etruscans.

Under Romulus andNuma Pompilius,the people were said to have been divided into thirtycuriaeand threetribes.Few Etruscan words enteredLatin,but the names of at least two of the tribes –RamnesandLuceres– seem to be Etruscan. The last kings may have borne the Etruscan titlelucumo,while theregaliawere traditionally considered of Etruscan origin – the golden crown, the sceptre, thetoga palmata(a special robe), thesella curulis(curule chair), and above all the primary symbol of state power: thefasces.The latter was a bundle of whipping rods surrounding a double-bladedaxe,carried by the king'slictors.An example of the fasces are the remains of bronze rods and the axe from a tomb in EtruscanVetulonia.This allowed archaeologists to identify the depiction of a fasces on the gravesteleof Avele Feluske, who is shown as a warrior wielding the fasces. The most telling Etruscan feature is the wordpopulus,which appears as an Etruscan deity,Fufluns.

Roman families of Etruscan origin[edit]

- Ancharia gens

- Arruntia gens

- Caecinia gens

- Caelia gens

- Caesennia gens

- Ceionia gens

- Cilnia gens

- Herminia gens–Patrician

- Erucia gens

- Lartia gens– Patrician

- Perpernia gens

- Persia gens

- Rasinia gens

- Sanquinia gens

- Spurinnia gens

- Tapsennia gens

- Tarquinia gens– Patrician (?)

- Tarquitia gens– Patrician

- Urgulania gens

- Verginia gens– Patrician

- Volumnia gens– Patrician

Society[edit]

Government[edit]

The historical Etruscans had achieved astatesystem of society, with remnants of thechiefdomand tribal forms. Rome was in a sense the first Italic state, but it began as an Etruscan one. It is believed that the Etruscan government style changed from totalmonarchytooligarchicrepublic(as the Roman Republic) in the 6th century BC.[105]

The government was viewed as being a central authority, ruling over all tribal and clan organizations. It retained the power of life and death; in fact, thegorgon,an ancient symbol of that power, appears as a motif in Etruscan decoration. The adherents to this state power were united by a common religion. Political unity in Etruscan society was the city-state, which was probably the referent ofmethlum,"district". Etruscan texts name quite a number ofmagistrates,without much of a hint as to their function: Thecamthi,theparnich,thepurth,thetamera,themacstrev,and so on. The people were themech.

Family[edit]

The princely tombs were not of individuals. The inscription evidence shows that families were interred there over long periods, marking the growth of the aristocratic family as a fixed institution, parallel to thegensat Rome and perhaps even its model. The Etruscans could have used any model of the eastern Mediterranean. That the growth of this class is related to the new acquisition of wealth through trade is unquestioned. The wealthiest cities were located near the coast. At the center of the society was the married couple,tusurthir.The Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized pairing.

Similarly, the behavior of some wealthy women is not uniquely Etruscan. The apparent promiscuous revelry has a spiritual explanation. Swaddling and Bonfante (among others) explain that depictions of the nude embrace, or symplegma, "had the power to ward off evil", as did baring the breast, which was adopted bywestern cultureas anapotropaic device,appearing finally on the figureheads of sailing ships as a nude female upper torso. It is also possible that Greek and Roman attitudes to the Etruscans were based on a misunderstanding of the place of women within their society. In both Greece and the earliest Republican Rome, respectable women were confined to the house and mixed-sex socialising did not occur. Thus, the freedom ofwomen within Etruscan societycould have been misunderstood as implying their sexual availability.[106]It is worth noting that a number of Etruscan tombs carry funerary inscriptions in the form "X son of (father) and (mother)", indicating the importance of the mother's side of the family.[106]

Military[edit]

The Etruscans, like the contemporary cultures ofAncient GreeceandAncient Rome,had a significant military tradition. In addition to marking the rank and power of certain individuals, warfare was a considerable economic advantage to Etruscan civilization. Like many ancient societies, the Etruscans conducted campaigns during summer months, raiding neighboring areas, attempting to gain territory and combatingpiracyas a means of acquiring valuable resources, such as land, prestige, goods, and slaves. It is likely that individuals taken in battle would be ransomed back to their families and clans at high cost. Prisoners could also potentially be sacrificed on tombs to honor fallen leaders of Etruscan society, not unlike the sacrifices made byAchillesforPatrocles.[107][108][109]

- 550 BC: Etruscan-Puniccoalition against Greece off the coast of Corsica

- 540 BC:naval victory at Alalia

- 524 BC: Defeat atCymeagainst the Greeks

- 510 BC: Fall of the Etruscan kingship ofLucius Tarquinius Superbusin Rome

- 508 BC:Lars Porsenabesieges Rome

- 508 BC: War betweenClusium and Aricia

- 482 BC: Beginning of the conflict betweenVeiiand Rome

- 474 BC: Defeat of the Etruscans againstSyracusein theBattle of Cyme(also Cumae)

- 430 BC 406 BC: Defeat against theSamnitesinCampania

- 406 BC: Siege of Veii by Rome

- 396 BC: Destruction of Veii by Rome

- from 396 BC: Invasion of the Celts into thePo Valley

- 384 BC: Plunder ofPyrgi(Santa Severa) byDionysius I of Syracuse

- 358 BC: Alliance ofTarquiniaandCerveteriagainst Rome

- 310 BC: Defeat against the Romans atLake Vadimone

- 300 BC: Pyrgi becomes a Roman colony

- 280 BC: Defeat ofVulciagainst Rome

- 264 BC 100 BC: Defeat ofVolsiniiagainst Rome

- 260 BC: Subjugation by the Gauls in the Po Valley

- 205 BC: Support ofScipioin the campaign againstHannibal

- 183 BC: Foundation of the Roman colony inSaturnia

- 90 BC: Granting ofRoman citizenship

- 82 BC: Repression ofSullain Etruria

- 79 BC: Capitulation ofVolterra

- from 40 BC: Final Romanization of Etruria

Cities[edit]

The range of Etruscan civilization is marked byits cities.They were entirely assimilated by Italic,Celtic,or Roman ethnic groups, but the names survive from inscriptions and their ruins are of aesthetic and historic interest in most of the cities of central Italy. Etruscan cities flourished over most of Italy during theRoman Iron Age,marking the farthest extent of Etruscan civilization. They were gradually assimilated first by Italics in the south, then by Celts in the north and finally in Etruria itself by the growing Roman Republic.[107]

That many Roman cities were formerly Etruscan was well known to all the Roman authors. Some cities were founded by Etruscans in prehistoric times, and bore entirely Etruscan names. Others were colonized by Etruscans who Etruscanized the name, usuallyItalic.[108]

Culture[edit]

Agriculture[edit]

The Etruscans were aware of the techniques ofwater accumulation and conservationin Egypt, Mesopotamia and Greece. They built canals and dams to irrigate the land, and drained and reclaimed swamps. The archaeological remains of this infrastructure are still evident in the maritime southwestern parts ofTuscany.[110]

Vite maritatais aviticulturetechnique exploitingcompanion plantingnamed after theMaremmaregion of Italy which may be relevant toclimate change.[111]It was developed around the area by these early predecessors of the Romans who cultivated plant as nearly as possible in their natural habitat. Thevinesfrom which wine is made are a kind oflianathat naturally intertwine with trees such as maples or willows.[112]

Religion[edit]

The Etruscan system of belief was animmanentpolytheism;that is, all visible phenomena were considered to be a manifestation ofdivinepower and that power was subdivided intodeitiesthat acted continually on the world of man and could be dissuaded or persuaded in favor of human affairs. How to understand the will of deities, and how to behave, had been revealed to the Etruscans by two initiators,Tages,a childlike figure born from tilled land and immediately gifted with prescience, andVegoia,a female figure. Their teachings were kept in a series of sacred books. Three layers of deities are evident in the extensive Etruscan art motifs. One appears to be divinities of an indigenous nature:CathaandUsil,the sun;Tivr,the moon;Selvans,a civil god;Turan,the goddess of love;Laran,the god of war;Leinth,the goddess of death;Maris;Thalna;Turms;and the ever-popularFufluns,whose name is related in some way to the city ofPopuloniaand thepopulus Romanus,possibly, the god of the people.[113][114]

Ruling over this pantheon of lesser deities were higher ones that seem to reflect theIndo-Europeansystem: Tin orTinia,the sky,Unihis wife (Juno), andCel,the earth goddess. In addition, some Greek and Roman gods were inspired by the Etruscan system:Aritimi(Artemis),Menrva(Minerva), Pacha (Dionysus). The Greek heroes taken fromHomeralso appear extensively in art motifs.[113][114]

Architecture[edit]

Relatively little is known about the architecture of the ancient Etruscans. They adapted the native Italic styles with influence from the external appearance ofGreek architecture.In turn,ancient Roman architecturebegan with Etruscan styles, and then accepted still further Greek influence.Roman templesshow many of the same differences in form to Greek ones that Etruscan temples do, but like the Greeks, use stone, in which they closely copy Greek conventions. The houses of the wealthy were evidently often large and comfortable, but the burial chambers of tombs, often filled with grave-goods, are the nearest approach to them to survive. In the southern Etruscan area, tombs have large rock-cut chambers under atumulusin largenecropoleis,and these, together with some city walls, are the only Etruscan constructions to survive. Etruscan architecture is not generally considered as part of the body of Greco-Romanclassical architecture.[115]

Art and music[edit]

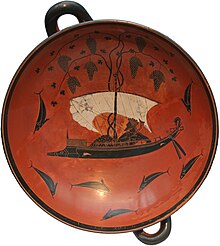

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization between the 9th and 2nd centuries BC. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta (particularly lifesize onsarcophagior temples), wall-painting andmetalworking(especially engraved bronze mirrors). Etruscan sculpture in cast bronze was famous and widely exported, but few large examples have survived (the material was too valuable, and recycled later). In contrast to terracotta and bronze, there was apparently little Etruscan sculpture in stone, despite the Etruscans controlling fine sources of marble, includingCarrara marble,which seems not to have been exploited until the Romans. Most surviving Etruscan art comes from tombs, including all thefrescowall-paintings, a minority of which show scenes of feasting and some narrative mythological subjects.[116]

Buccherowares in black were the early and native styles of fine Etruscan pottery. There was also a tradition of elaborateEtruscan vase painting,which sprung from its Greek equivalent; the Etruscans were the main export market forGreek vases.Etruscan temples were heavily decorated with colorfully painted terracottaantefixesand other fittings, which survive in large numbers where the wooden superstructure has vanished. Etruscan art was strongly connected toreligion;the afterlife was of major importance in Etruscan art.[117]

The Etruscan musical instruments seen in frescoes and bas-reliefs are different types of pipes, such as theplagiaulos(the pipes ofPanorSyrinx), the alabaster pipe and the famous double pipes, accompanied on percussion instruments such as thetintinnabulum,tympanumandcrotales,and later by stringed instruments like thelyreandkithara.

Language[edit]

Etruscans left around 13,000inscriptionswhich have been found so far, only a small minority of which are of significant length. Attested from 700 BC to AD 50, the relation of Etruscan to other languages has been a source of long-running speculation and study. The Etruscans are believed to have spoken aPre-Indo-European[118][119][120]andPaleo-European language,[121]and the majority consensus is that Etruscan is related only to other members of what is called theTyrsenian language family,which in itself is anisolate family,that is unrelated directly to other known language groups. SinceRix(1998), it is widely accepted that the Tyrsenian family groupsRaeticandLemnianare related to Etruscan.[18]

Literature[edit]

Etruscan texts, written in a space of seven centuries, use a form of theGreek alphabetdue to close contact between the Etruscans and the Greek colonies atPithecusaeandCumaein the 8th century BC (until it was no longer used, at the beginning of the 1st century AD). Etruscan inscriptions disappeared fromChiusi,PerugiaandArezzoaround this time. Only a few fragments survive, religious and especially funeral texts, most of which are late (from the 4th century BC). In addition to the original texts that have survived to this day, there are a large number of quotations and allusions from classical authors. In the 1st century BC,Diodorus Siculuswrote that literary culture was one of the great achievements of the Etruscans. Little is known of it and even what is known of their language is due to the repetition of the same few words in the many inscriptions found (by way of the modern epitaphs) contrasted in bilingual or trilingual texts with Latin andPunic.Out of the aforementioned genres, is just one such Volnio (Volnius) cited in classical sources mentioned.[122]With a few exceptions, such as theLiber Linteus,theonly written records in the Etruscan languagethat remain are inscriptions, mainly funerary. The language is written in theEtruscan alphabet,a script related to the earlyEuboean Greek alphabet.[123]Many thousand inscriptions in Etruscan are known, mostlyepitaphs,and a fewvery short textshave survived, which are mainly religious. Etruscan imaginative literature is evidenced only in references by later Roman authors, but it is evident from their visual art that the Greek myths were well-known.[124]

With the founding ofPithekussaionIschiaand Kyme (lat.Cumae) inCampaniain the course of theGreek colonization,the Etruscans came under the influence of theGreek culturein the 8th century BC. The Etruscans adopted analphabetfrom the western Greek colonists that came from their homeland, the EuboeanChalkis.This alphabet from Cumae is therefore also called Euboean[125]or Chalcidian[126]Alphabet. The oldest written records of the Etruscans date from around 700 BC.[127]

| Euboean alphabet[128] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transcription | A | B | G | D | E | V | Z | H | TH | I | K | L | M | N | X | O | P | Ś | Q | R | S | T | U | X | PH | CH |

One of the oldest Etruscan written documents is found on thetablet of Marsiliana d’Albegnafrom the hinterland ofVulci,which is now kept in theNational Archaeological MuseumofFlorence.A western Greek model alphabet is engraved on the edge of thiswax tabletmade ofivory.In accordance with later Etruscan writing habits, thelettersin this model alphabet were mirrored and arranged from right to left:

| Early Etruscan alphabet[129] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transcription | A | B | C | D | E | F | Z | H | TH | I | K | L | M | N | S | O | P | SH | Q | R | S | T | U | X | PH | KH |

The script with these letters was first used in southern Etruria around 700 BC in the EtruscanCisra(lat.Caere), today'sCerveteri.[130]The science of writing quickly reached central and northern Etruria. From there, the alphabet spread fromVolterra(Etr.Velathri) toFelsina,today'sBologna,and later fromChiusi(Etr.Clevsin) to the Po Valley. In southern Etruria, the writing spread fromTarquinia(Etr.Tarchna) andVeii(Etr.Veia) further south to Campania, which was controlled by the Etruscans at the time.[131]In the following centuries the Etruscans consistently used the letters mentioned, so that thedecipheringof the Etruscan inscriptions is not a problem. As in Greek, the characters were subject to regional and temporal changes. Overall, one can distinguish an archaic script from the 7th to 5th centuries from a more recent script from the 4th to 1st centuries BC, in which some characters were no longer used, including the X for a sh sound. In addition, in writing and language, the emphasis on the first syllable meant that internal vowels were not reproduced, e.g.Menrvainstead ofMenerva.[132]Accordingly,linguistsalso distinguish between Old and New Etruscan.[133]

Alongside thetablet of Marsiliana d’Albegna,around 70 objects with model alphabets have been preserved from the early period.[134]The most famous of these are:

- Alabastronfrom theRegolini-Galassi tombin Cerveteri

- Bucchero amphora from Formello

- Bucchero cockerel from Viterbo

- Buccherovessel from the necropolis of Sorbo near Cerveteri

As all four artifacts date from the 7th century B.C. come from, the alphabets are always written clockwise.[135]The last object has the special feature that, in addition to the letters of the alphabet, almost all consonants are shown in sequence in connection with the vowels I, A, U and E (Syllabary). This syllabic writing system was probably used to practice the written characters.[136]

The most important Etruscan written monuments that contain a large number of words include:

- Liber Linteus(Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis) – ritual text with around 1400 words

- Clay Tablet of Capua(TabulaorTegula Capuana) – ritual text as a bustrophedon with 62 lines and around 300 words

- Tablet of Cortona(Tabula Cortonensis) – contract text with a length of 32 lines and about 200 words

- Cippus Perusinus– travertine block with 46 lines and about 125 words from nearPerugia

- Pyrgi Tablets– parallel texts in Etruscan andPunic script

- Sarcophagus of Laris Pulenas– grave inscription of Laris Pulena with nine lines of text on a sarcophagus scroll

- Liver of Piacenza– model of a sheep's liver with 40 inscriptions

- Lead Plaque of Magliano– sacrificial instructions with 70 words

- Lead strip from Santa Marinella– two fragments of a sacrificial vow

- Building inscription of the tomb of San Manno near Perugia – 30-word consecration inscription

- Aryballe Poupé– Clockwise dedication inscription on a bucchero bottle

- Tuscanian dice– Two dice with the numbers 1 to 6

No further Etruscan literature has survived and from the early 1st century AD, inscriptions with Etruscan characters have ceased to exist. All existing ancient Etruscan written documents are systematically collected in theCorpus Inscriptionum Etruscarum.

In the middle of the 7th century BC, the Romans adopted the Etruscan writing system and letters. In particular, they used the three different characters C, K and Q for a K sound. Z was also initially adopted into the Roman alphabet, although the affricate TS did not occur in the Latin language. Later, Z was replaced in the alphabet by the newly formed letter G, which was derived from C, and Z was finally placed at the end of the alphabet.[137]The letters Θ, Φ and Ψ were omitted by the Romans because the corresponding aspirated sounds did not occur in their language.

The Etruscan alphabet spread across the northern and central parts of the Italian peninsula. It is assumed that the formation of theOscan script,probably in the 6th century BC, was fundamentally influenced by Etruscan. The characters of theUmbrian,FaliscanandVeneticlanguages can also be traced back to Etruscan alphabets.[138]

See also[edit]

| History ofItaly |

|---|

|

|

|

| Ancient history |

|---|

| Preceded byprehistory |

|

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^abcdeBartoloni, Gilda, ed. (2012).Introduzione all'Etruscologia(in Italian). Milan: Hoepli.ISBN978-8820348700.

- ^Potts, Charlotte R.; Smith, Christopher J. (2022)."The Etruscans: Setting New Agendas".Journal of Archaeological Research.30(4): 597–644.doi:10.1007/s10814-021-09169-x.hdl:10023/24245.

- ^Goring, Elizabeth (2004).Treasures from Tuscany: the Etruscan legacy.Edinburgh: National Museums Scotland Enterprises Limited. p. 13.ISBN978-1901663907.

- ^Leighton, Robert (2004).Tarquinia. An Etruscan City.Duckworth Archaeological Histories Series. London: Duckworth Press. p. 32.ISBN0-7156-3162-4.

- ^Camporeale, Giovannangelo,ed. (2001).The Etruscans Outside Etruria.Translated by Hartmann, Thomas Michael. Los Angeles: Getty Trust Publications (published 2004).

- ^Della Fina, Giuseppe (2005).Etruschi, la vita quotidiana(in Italian). Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider. p. 15.ISBN9788882653330.

- ^abBarker, Graeme;Rasmussen, Tom(2000).The Etruscans.The Peoples of Europe. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 44.ISBN978-0-631-22038-1.

- ^abcDe Grummond, Nancy T.(2014). "Ethnicity and the Etruscans". In McInerney, Jeremy (ed.).A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean.Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 405–422.doi:10.1002/9781118834312.ISBN9781444337341.

- ^abcTurfa, Jean MacIntosh(2017). "The Etruscans". In Farney, Gary D.; Bradley, Gary (eds.).The Peoples of Ancient Italy.Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 637–672.doi:10.1515/9781614513001.ISBN978-1-61451-520-3.

- ^abcShipley, Lucy (2017). "Where is home?".The Etruscans: Lost Civilizations.London: Reaktion Books. pp. 28–46.ISBN9781780238623.

- ^abcBenelli, Enrico (2021). "Le origini. Dai racconti del mito all'evidenza dell'archeologia".Gli Etruschi(in Italian). Milan: Idea Libri-Rusconi Editore. pp. 9–24.ISBN978-8862623049.

- ^abNeri, Diana (2012). "1.1 Il periodo villanoviano nell'Emilia occidentale".Gli etruschi tra VIII e VII secolo a.C. nel territorio di Castelfranco Emilia (MO)(in Italian). Firenze: All'Insegna del Giglio. p. 9.ISBN978-8878145337.

Il termine "Villanoviano" è entrato nella letteratura archeologica quando, a metà dell '800, il conte Gozzadini mise in luce le prime tombe ad incinerazione nella sua proprietà di Villanova di Castenaso, in località Caselle (BO). La cultura villanoviana coincide con il periodo più antico della civiltà etrusca, in particolare durante i secoli IX e VIII a.C. e i termini di Villanoviano I, II e III, utilizzati dagli archeologi per scandire le fasi evolutive, costituiscono partizioni convenzionali della prima età del Ferro

- ^abcBartoloni, Gilda (2012) [2002].La cultura villanoviana. All'inizio della storia etrusca(in Italian) (III ed.). Roma: Carocci editore.ISBN9788843022618.

- ^abColonna, Giovanni(2000). "I caratteri originali della civiltà Etrusca". In Torelli, Mario (ed.).Gi Etruschi(in Italian). Milano: Bompiani. pp. 25–41.

- ^abBriquel, Dominique(2000). "Le origini degli Etruschi: una questione dibattuta fin dall'antichità". In Torelli, Mario (ed.).Gi Etruschi(in Italian). Milano: Bompiani. pp. 43–51.

- ^abBartoloni, Gilda (2000). "Le origini e la diffusione della cultura villanoviana". In Torelli, Mario (ed.).Gi Etruschi(in Italian). Milano: Bompiani. pp. 53–71.

- ^abcMoser, Mary E. (1996)."The origins of the Etruscans: new evidence for an old question".InHall, John Franklin(ed.).Etruscan Italy: Etruscan Influences on the Civilizations of Italy from Antiquity to the Modern Era.Provo, Utah: Museum of Art, Brigham Young University. pp.29- 43.ISBN0842523340.

- ^abcRix, Helmut (2008). "Etruscan". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.).The Ancient Languages of Europe.Cambridge University Press. pp.141–64.ISBN9780521684958.

- ^"A good map of the Italian range and cities of the culture at the beginning of its history".mysteriousetruscans.com.

- ^The topic of the "League of Etruria" is covered in Freeman, pp. 562–65.

- ^Livius, Titus.Ab Urbe Condita Libri[The History of Rome]. Book V, Section 33.

The passage identifies theRaetiias a remnant of the 12 cities "beyond theApennines".

- ^Polybius."Campanian Etruscans mentioned".II.17.

- ^The entire subject with complete ancient sources in footnotes was worked up by George Dennis in hisIntroduction.In theLacusCurtiustranscription, the references in Dennis's footnotes link to the texts in English or Latin; the reader may also find the English of some of them onWikiSourceor other Internet sites. As the work has already been done by Dennis and Thayer, the complete work-up is not repeated here.

- ^M. Cary; H.H. Scullard (1979).A History of Rome(3rd ed.). Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 28.ISBN0-312-38395-9.

- ^Bonfante, Giuliano;Bonfante, Larissa(2002) [1983].The Etruscan language. An introduction(II (Revised) ed.). Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.ISBN0719055407.

- ^"Etruscan alphabet and language".omniglot.com.Retrieved2022-02-16.

- ^Sassatelli, Giuseppe."Celti ed Etruschi nell'Etruria Padana e nell'Italia settentrionale"(PDF)(in Italian).

- ^Carlo Amendola (2019-08-28)."Etruschi e Celti della Gallia meridionale – parte 1".CelticWorld(in Italian).Retrieved2022-02-15.

- ^Rasenna comes fromDionysius of Halicarnassus.Roman Antiquities.I.30.3.The syncopated form, Rasna, is inscriptional and is inflected.

- ^The topic is covered in Pallottino, p. 133.

- ^Some inscriptions, such as the cippus of Cortona, feature the Raśna (pronounced Rashna) alternative, as is described atBodroghy, Gabor Z."Origins".The Palaeolinguistic Connection.Etruscan. Archived fromthe originalon 16 April 2008.

- ^Τυρρηνός,Τυρσηνός.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;A Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.

- ^Tyrrheni.Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short.A Latin DictionaryonPerseus Project.

- ^Thomson de Grummond, Nancy (2006).Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend.Philadelphia: Penn Museum of Archaeology. pp. 201–208.ISBN9781931707862.

- ^According to Félix Gaffiot'sDictionnaire Illustré Latin Français,the major authors of theRoman Republic(Livy,Cicero,Horace,and others) used the termTusci.Cognate words developed, includingTusciaandTusculanensis.Tuscīwas clearly the principal term used to designate things Etruscan;EtruscīandEtrusia/Etrūriawere used less often, mainly by Cicero and Horace, and they lack cognates.

- ^According to the"Online Etymological Dictionary".the English use ofEtruscandates from 1706.

- ^Tusci.Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short.A Latin DictionaryonPerseus Project.

- ^Weiss, Michael."'Cui bono?' The beneficiary phrases of the third Iguvine table "(PDF).Ithaca, New York: Cornell University.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^Carl Darling Buck(1904).Introduction: A Grammar of Oscan and Umbrian.Boston: Gibb & Company.

- ^Partridge, Eric (1983). "tower".Origins.New York: Greenwich House. p. 730.ISBN9780517414255.

- ^abThe Bonfantes (2003), p. 51.

- ^τύρσιςinLiddellandScott.

- ^Partridge (1983)

- ^Bonfante, Giuliano; Bonfante, Larissa (2002).The Etruscan Language: An Introduction, Revised Edition.Manchester University Press. p. 51.ISBN978-0719055409.

- ^Book I, Section 30.

- ^Beekes, R.Etymological Dictionary of GreekBrill (2010) pp.1520-1521

- ^Kretschmer, Paul. "Nordische Lehnwörter im Altgriechischen" inGlotta22 (1934) pp. 110 ff.

- ^Strauss Clay 2016,pp. 32–34.

- ^Hesiod,Theogony1015.

- ^Homeric Hymn to Dionysus, 7.7–8

- ^John Pairman Brown,Israel and Hellas,Vol. 2 (2000) p. 211

- ^Strabo.Geography.Book VI, Chapter II. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University.Archivedfrom the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^6.137

- ^4.109

- ^abStrabo.Geography.Book V, Chapter II. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University.Archivedfrom the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^1.94

- ^Dionysius of Halicarnassus.Roman Antiquities.1.28–3.

- ^Morritt, Robert D. (2010).Stones that Speak.p. 272.

- ^abDionysius of Halicarnassus.Roman Antiquities.Book I, Chapters 30 1.

- ^Livius, Titus.Ab Urbe Condita Libri[The History of Rome]. Book 5.

- ^Plinius Secundus, Gaius.Naturalis Historia, Liber III, 133(in Latin).

- ^Wallace, Rex E.(2010). "Italy, Languages of". In Gagarin, Michael (ed.).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome.Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 97–102.doi:10.1093/acref/9780195170726.001.0001.ISBN9780195170726.

Etruscan origins lie in the distant past. Despite the claim by Herodotus, who wrote that Etruscans migrated to Italy from Lydia in the eastern Mediterranean, there is no material or linguistic evidence to support this. Etruscan material culture developed in an unbroken chain from Bronze Age antecedents. As for linguistic relationships, Lydian is an Indo-European language. Lemnian, which is attested by a few inscriptions discovered near Kamania on the island of Lemnos, was a dialect of Etruscan introduced to the island by commercial adventurers. Linguistic similarities connecting Etruscan with Raetic, a language spoken in the sub-Alpine regions of northeastern Italy, further militate against the idea of eastern origins.

- ^Pallottino, Massimo(1947).L'origine degli Etruschi(in Italian). Rome: Tumminelli.

- ^Briquel, Dominique(2000). "Le origini degli Etruschi: una questione dibattuta sin dall'antichità". InTorelli, Mario(ed.).Gli Etruschi(in Italian). Milan: Bompiani. pp. 43–51.

- ^Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther, eds. (2014).The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization.Oxford Companions (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 291–292.ISBN9780191016752.

Briquel's convincing demonstration that the famous story of an exodus, led by Tyrrhenus from Lydia to Italy, was a deliberate political fabrication created in the Hellenized milieu of the court at Sardis in the early 6th cent. BCE.

- ^Briquel, Dominique (2013). "Etruscan Origins and the Ancient Authors". In Turfa, Jean (ed.).The Etruscan World.London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 36–56.ISBN978-0-415-67308-2.

- ^Briquel, Dominique(1990). "Le problème des origines étrusques".Lalies.Sessions de linguistique et de littérature (in French). Paris: Presses de l'Ecole Normale Supérieure (published 1992): 7–35.

- ^abBartoloni, Gilda (2014). "Gli artigiani metallurghi e il processo formativo nelle" Origini "degli Etruschi"."Origines": percorsi di ricerca sulle identità etniche nell'Italia antica.Mélanges de l'École française de Rome: Antiquité (in Italian). Vol. 126–2. Rome: École française de Rome.ISBN978-2-7283-1138-5.

- ^Bagnasco Gianni, Giovanna. "Origine degli Etruschi". In Bartoloni, Gilda (ed.).Introduzione all'Etruscologia(in Italian). Milan: Ulrico Hoepli Editore. pp. 47–81.

- ^Stoddart, Simon(1989). "Divergent trajectories in central Italy 1200–500 BC". In Champion, Timothy C. (ed.).Centre and Periphery – Comparative Studies in Archaeology.London and New York: Taylor & Francis (published 2005). pp. 89–102.

- ^Burkert, Walter (1992).The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age.Enciclopedia del Mediterraneo. London: Thames and Hudson.

- ^d'Agostino, Bruno (2003). "Teorie sull'origine degli Etruschi".Gli Etruschi.Enciclopedia del Mediterraneo (in Italian). Vol. 26. Milan: Jaca Book. pp. 10–19.

- ^de Grummond, Nancy Thomson (2014). "Ethnicity and the Etruscans".Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean.Chichester, Uk: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 413–414.

The facial features, however, are not likely to constitute a true portrait, but rather partake of a formula for representing the male in Etruria in Archaic art. It has been observed that the formula used—with the face in profile, showing almond-shaped eyes, a large nose, and a domed up profile of the top of the head—has its parallels in images from the eastern Mediterranean. But these features may show only artistic conventions and are therefore of limited value for determining ethnicity.

- ^Bianchi Bandinelli, Ranuccio(1984). "Il problema del ritratto".L'arte classica(in Italian). Roma:Editori Riuniti.

- ^A Ciba Foundation Symposium (1959) [1958].Wolstenholme, Gordon;O'Connor, Cecilia M. (eds.).Medical Biology and Etruscan Origins.London: J & A Churchill Ltd.ISBN978-0-470-71493-5.

- ^abcPerkins, Phil (2017)."Chapter 8: DNA and Etruscan identity".In Naso, Alessandro (ed.).Etruscology.Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 109–118.ISBN978-1934078495.

- ^abcPerkins, Phil (2009). "DNA and Etruscan identity". In Perkins, Phil; Swaddling, Judith (eds.).Etruscan by Definition: Papers in Honour of Sybille Haynes.London: The British Museum Research Publications. pp. 95–111.ISBN978-0861591732.173.

- ^Reich, David(2018). "Ancient DNA Opens the Floodgates".Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past.Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–59.ISBN9780198821250.

But mitochondrial DNA only records information on the entirely female line, a tiny fraction of the many tens of thousands of lineages that have contributed to any person's genome. To understand what really happened in an individual's history, it is incomparably more valuable to examine all ancestral lineages together.

- ^Posth, Cosimo; Zaro, Valentina; Spyrou, Maria A. (September 24, 2021)."The origin and legacy of the Etruscans through a 2000-year archeogenomic time transect".Science Advances.7(39). Washington DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science: eabi7673.Bibcode:2021SciA....7.7673P.doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi7673.PMC8462907.PMID34559560.

- ^abAntonio, Margaret L.; Gao, Ziyue; M. Moots, Hannah (2019)."Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean".Science.366(6466). Washington D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science (published November 8, 2019): 708–714.Bibcode:2019Sci...366..708A.doi:10.1126/science.aay6826.hdl:2318/1715466.PMC7093155.PMID31699931.

Interestingly, although Iron Age individuals were sampled from both Etruscan (n=3) and Latin (n=6) contexts, we did not detect any significant differences between the two groups with f4 statistics in the form of f4(RMPR_Etruscan, RMPR_Latin; test population, Onge), suggesting shared origins or extensive genetic exchange between them.

- ^Antonio et al. 2019,p. 3.

- ^Antonio et al. 2019,p. 2.

- ^Antonio et al. 2019,Table 2 Sample Information, Rows 33-35.

- ^Leonardi, Michela; Sandionigi, Anna; Conzato, Annalisa; Vai, Stefania; Lari, Martina (2018)."The female ancestor's tale: Long-term matrilineal continuity in a nonisolated region of Tuscany".American Journal of Physical Anthropology.167(3). New York City: John Wiley & Sons (published September 6, 2018): 497–506.doi:10.1002/ajpa.23679.PMID30187463.S2CID52161000.

- ^Claassen, Horst; Wree, Andreas (2004)."The Etruscan skulls of the Rostock anatomical collection – How do they compare with the skeletal findings of the first thousand years B.C.?".Annals of Anatomy.186(2). Amsterdam: Elsevier: 157–163.doi:10.1016/S0940-9602(04)80032-3.PMID15125046.

Seven Etruscan skulls were found in Corneto Tarquinia in the years 1881 and 1882 and were given as [a] present to Rostock's anatomical collection in 1882. The origin of the Etruscans who were contemporary with the Celts is not yet clear; according to Herodotus they had emigrated from Lydia in Asia Minor to Italy. To fit the Etruscan skulls into an ethnological grid they were compared with skeletal remains of the first thousand years B.C.E. All skulls were found to be male; their age ranged from 20 to 60 years, with an average age of about thirty. A comparison of the median sagittal outlines of the Etruscan skulls and the contemporary Hallstatt-Celtic skulls from North Bavaria showed that the former were shorter and lower. Maximum skull length, minimum frontal breadth, ear bregma height, bizygomatical breadth and orbital breadth of the Etruscan skulls were statistically significantly less developed compared to Hallstatt-Celtics from North Bavaria. In comparison to other contemporary skeletal remains the Etruscan skulls had no similarities in common with Hallstatt-Celtic skulls from North Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg but rather with Hallstatt-Celtic skulls from Hallstatt in Austria. Compared to chronologically adjacent skeletal remains the Etruscan skulls did not show similarities with Early Bronze Age skulls from Moravia but with Latène-Celtic skulls from Manching in South Bavaria. Due to the similarities of the Etruscan skulls with some Celtic skulls from South Bavaria and Austria, it seems more likely that the Etruscans were original inhabitants of Etruria than immigrants.

- ^Ghirotto, Silvia; Tassi, Francesca; Fumagalli, Erica; Colonna, Vincenza; Sandionigi, Anna; Lari, Martina; Vai, Stefania; Petiti, Emmanuele; Corti, Giorgio; Rizzi, Ermanno; De Bellis, Gianluca; Caramelli, David; Barbujani, Guido (6 February 2013)."Origins and evolution of the Etruscans' mtDNA".PLOS ONE.8(2): e55519.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...855519G.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055519.PMC3566088.PMID23405165.

- ^Tassi, Francesca; Ghirotto, Silvia; Caramelli, David; Barbujani, Guido; et al. (2013). "Genetic evidence does not support an Etruscan origin in Anatolia".American Journal of Physical Anthropology.152(1): 11–18.doi:10.1002/ajpa.22319.PMID23900768.

- ^abC. Vernesi e Altri (March 2004)."The Etruscans: A population-genetic study".American Journal of Human Genetics.74(4): 694–704.doi:10.1086/383284.PMC1181945.PMID15015132.

- ^Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen (2004)."Etruscan artifacts".American Journal of Human Genetics.75(5): 919–920.doi:10.1086/425180.PMC1182123.PMID15457405.

- ^Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen (2005)."Mosaics of ancient mitochondrial DNA: positive indicators of nonauthenticity".European Journal of Human Genetics.13(10): 1106–1112.doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201476.PMID16077732.S2CID19958417.

- ^Gilbert, Marcus Thomas Pius (2005)."Assessing ancient DNA studies".Trends in Ecology & Evolution (TREE).20(10): 541–544.doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.07.005.PMID16701432.

- ^Krause, Johannes;Trappe, Thomas (2021) [2019].A Short History of Humanity: A New History of Old Europe[Die Reise unserer Gene: Eine Geschichte über uns und unsere Vorfahren]. Translated by Waight, Caroline (I ed.). New York: Random House. p. 217.ISBN9780593229422.

It's likely that Basque, Paleo-Sardinian, Minoan, and Etruscan developed on the continent in the course of the Neolithic Revolution. Sadly, the true diversity of the languages that once existed in Europe will never be known.

- ^abGilda Bartoloni,"La cultura villanoviana", inEnciclopedia dell'Arte Antica,Treccani, Rome 1997, vol. VII, p. 1173 e s 1970, p. 922. (Italian)

- ^Walter Burkert,The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age,1992.

- ^abGiovanna Bermond Montanari (2004)."L'Italia preromana. I siti etruschi: Bologna"(in Italian).Treccani.RetrievedOctober 12,2019.

- ^abBonfante, Larissa (1986).Etruscan life and afterlife.Wayne State University Press.ISBN978-0-8143-1813-3.Retrieved2009-04-22– via Google Books.

- ^abJohn Franklin Hall (1996).Etruscan Italy.Indiana University Press.ISBN978-0-8425-2334-9.Retrieved22 April2009– via Google Books.

- ^Livy VII.21

- ^"Etruschi"[Etruscans].Dizionario di storia(in Italian).Treccani.Retrieved29 March2016.

- ^ab"The Etruscan League of 12".mysteriousetruscans.com.2 April 2009.Retrieved25 April2015.

- ^Davis, Madison; Frankforter, Daniel (2004)."The Shakespeare Name Dictionary".Taylor & Francis.ISBN9780203642276.Retrieved2011-09-14.

- ^Cunningham, Reich (2006).Cultures and Values: A survey of the humanities.Thomson/Wadsworth. p.92.ISBN978-0534582272.

The later Romans' own grandiose picture of the early days of their city was intended to glamorize its origins, but only with the arrival of the Etruscans did anything like an urban center begin to develop.

- ^Hughes (2012).Rome: A cultural, visual, and personal history.p. 24.

Some Roman technical achievements began in Etruscan expertise. Though the Etruscans never came up with an aqueduct, they were good at drainage, and hence they were the ancestors of Rome's monumental sewer systems.

- ^Tacitus, Cornelius.The Annals & The Histories.Trans. Alfred Church and William Brodribb. New York, 2003.

- ^Jean-Paul Thuillier (2006).Les Étrusques(in French). Éditions du Chêne. p. 142.ISBN2842776585.

- ^abBriquel, Dominique; Svensson Pär (2007). Etruskerna. Alhambras pocket encyklopedi, 99-1532610-6; 88 (1. uppl.). Furulund: Alhambra.ISBN9789188992970

- ^abTorelli, Mario (2000).The Etruscans.Rizzoli International Publications.

- ^abDupey, Trevor.The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History.Rizzoli Harper Collins Publisher.

- ^Dora Jane Hamblin (1975).The Etruscans.Time Life Books.

- ^"The Etruscans and agriculture".Un Mondo Ecosostenibile.21 November 2022.Archivedfrom the original on Jan 13, 2024.

- ^Limbergen, Dimitri Van (2024-01-04)."Ancient Roman wine production may hold clues for battling climate change".The Conversation.Archivedfrom the original on Feb 29, 2024.

- ^Mazzeo, Jacopo (June 6, 2023)."Vite Maritata, an Ancient Vine-Growing Technique, Makes a Comeback".Wine Enthusiast Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on Jan 13, 2024.

- ^abGrummond, De; Thomson, Nancy (2006).Etruscan Mythology, Sacred History and Legend: An Introduction.University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology.

- ^abSimon, Erika (20 April 2009).The religion of the Etruscans.University of Texas Press.ISBN978-0-292-70687-3– via Google Books.

- ^Boëthius, Axel; Ling, Roger; Rasmussen, Tom (1994).Etruscan and early Roman architecture.Yale University Press.

- ^"I banchetti etruschi"(in Italian).Retrieved24 November2021.

- ^Spivey, Nigel (1997).Etruscan Art.London: Thames and Hudson.

- ^Massimo Pallottino,La langue étrusque Problèmes et perspectives,1978.

- ^Mauro Cristofani,Introduction to the study of the Etruscan,Leo S. Olschki, 1991.

- ^Romolo A. Staccioli,The "mystery" of the Etruscan language,Newton & Compton publishers, Rome, 1977.

- ^Haarmann, Harald(2014). "Ethnicity and Language in the Ancient Mediterranean". In McInerney, Jeremy (ed.).A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean.Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 17–33.doi:10.1002/9781118834312.ch2.ISBN9781444337341.

- ^Varro,De lingua Latina,5.55.

- ^Maras, Daniele F. (2015). "Etruscan and Italic Literacy and the Case of Rome". In Bloome, W. Martin (ed.).A Companion to Ancient Education.Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. p. 202.

- ^Nielsen, Marjatta; Rathje, Annette. "Artumes in Etruria—the Borrowed Goddess". In Fischer-Hansen, Tobias; Poulsen, Birte (eds.).From Artemis to Diana: The Goddess of Man and Beast.Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 261.

A massive Greek impact is clear especially in the coastal territory, which has led many to believe that the Etruscans were entirely Hellenized. Countless depictions show that Greek myths were, indeed, adopted and well-known to the Etruscans.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 14.

- ^Friedhelm Prayon:The Etruscans. History, religion, art.p. 38.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 56.

- ^Steven Roger Fischer:History of Writing.S. 138.

- ^Steven Roger Fischer:History of Writing.S. 140.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 14.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 54.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 81.

- ^Friedhelm Prayon:Die Etrusker. History, Religion, Art.pp. 38–40.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 55.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 133.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 14.

- ^Steven Roger Fischer:History of Writing.pp. 141–142.

- ^Larissa Bonfante, Giuliano Bonfante:The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.p. 117.

Sources[edit]

- Antonio, Margaret L.; et al. (November 8, 2019)."Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean".Science.366(6466).American Association for the Advancement of Science:708–714.Bibcode:2019Sci...366..708A.doi:10.1126/science.aay6826.PMC7093155.PMID31699931.

- Strauss Clay, Jenny(2016). "Visualizing Divinity: The Reception of theHomeric Hymnsin Greek Vase Painting ". In Faulkner, Andrew; Vergados, Athanassios; Schwab, Andreas (eds.).The Reception of the Homeric Hymns.Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 29–52.doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198728788.003.0002.ISBN9780191795510.

Further reading[edit]

- Bartoloni, Gilda (ed).Introduzione all'Etruscologia(in Italian). Milan: Hoepli, 2012.

- Sinclair Belland Carpino A. Alexandra (eds).A Companion to the Etruscans,Oxford; Chichester; Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2016.

- Bonfante, GiulianoandBonfante Larissa.The Etruscan Language: An Introduction.Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002.

- Bonfante, Larissa.Out of Etruria: Etruscan Influence North and South.Oxford: B.A.R., 1981.

- Bonfante, Larissa.Etruscan Life and Afterlife: A Handbook of Etruscan Studies.Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1986.

- Bonfante, Larissa.Etruscan Myths.London: British Museum Press, 2006.

- Briquel, Dominique.Les Étrusques, peuple de la différence,series Civilisations U, éditions Armand Colin, Paris, 1993.

- Briquel, Dominique.La civilisation étrusque,éditions Fayard, Paris, 1999.

- De Grummond, Nancy T.(2014).Ethnicity and the Etruscans.In McInerney, Jeremy (ed.).A Companion to Ethnicity in the Ancient Mediterranean.Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 405–422.

- Haynes, Sybille.Etruscan Civilization: A Cultural History.Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000.

- Izzet, Vedia.The Archaeology of Etruscan Society.New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Naso, Alessandro (ed).Etruscology,Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2017.

- Pallottino, Massimo.Etruscologia.Milan: Hoepli, 1942 (English ed.,The Etruscans.David Ridgway,editor. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1975).

- Shipley, Lucy.The Etruscans: Lost Civilizations,London: Reaktion Books, 2017.

- Smith, C.The Etruscans: a very short introduction,Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Spivey, Nigel.Etruscan Art.New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.