Fatawa 'Alamgiri

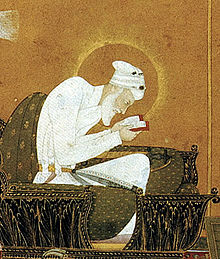

Manuscript of the Fatawa 'Alamgiri | |

| Author | 500 prominent Islamic scholars |

|---|---|

| Language | ArabicandPersian |

| Genre | Islamic law(Hanafi) |

| Publisher | EmperorAurangzeb |

Publication date | 1672 |

Fatawa 'Alamgiri,also known asAl-Fatawa al-'Alamgiriyya(Arabic:الفتاوى العالمكيرية) orAl-Fatawa al-Hindiyya(Arabic:الفتاوى الهندية), is a 17th-centuryshariabased compilation on statecraft, general ethics, military strategy, economic policy, justice and punishment, that served as the law and principal regulating body of theMughal Empire,during the reign of theMughalemperorMuhammad Muhiuddin Aurangzeb Alamgir.[1]It subsequently went on to become the reference legal text to enforce sharia in colonial South Asia in the 18th century through early 20th century,[2]and has been heralded as "the greatest digest ofMuslim lawduring theMughal India".[3][4]

Outline

[edit]Fatawa-e-Alamgiri was the work of many prominent scholars from different parts of the world, includingHejaz,principally from theHanafischool. In order to compile Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, emperor Aurangzeb gathered 500 experts in Islamic jurisprudence, 300 fromSouth Asia,100 fromIraqand 100 from theHejaz.Shaikh Nizam, a celebrated lawyer fromLahorewas appointed the chairman of the commission which would compile the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri.[5]The years long work of these scholars resulted in an Islamic code of law for South Asia, in the lateMughal Era.It consists of legal code on personal, family, slaves, war, property, inter-religious relations, transaction, taxation, economic and other law for a range of possible situations and their juristic rulings by thefaqīhof the time.[citation needed]

The collection comprises verses from theQur'an,supplemented byhadithnarratives, including those ofSahih al-Bukhari,Sahih Muslim,Sunan Abu DawoodandSahih at-Tirmidhi.[6]

The Fatawa is notable for several reasons:

- It spanned 30 volumes originally in various languages, but is now printed in modern editions as 6 volumes[7]

- It provided significant direct contribution to the economy ofSouth Asia,particularlyBengal Subah,waving theproto-industrialization.[8]

- It served as the basis of judicial law throughout the Mughal Empire

- It created a legal system that treated people differently based on their religion

In substance similar to otherHanafitexts,[9]the laws in Fatawa-i Alamgiri describe, among other things, the following:

Criminal and personal law

[edit]- Personal law for South Asian Muslims in the 18th century, their inheritance rights,[10]

- Personal law on gifts,[11]

- Apostatesneither have nor leave inheritance rights after they are executed,[12]

- The guardian of a Muslim girl may arrange her marriage with her consent,[13]

- A Muslim boy of understanding, requires the consent of his guardian to marry.[14]

- Laws establishing the paternity of a child arising from valid or invalid Muslim marriages,[15]

- A Muslim man with four wives must treat all of them justly, equally and each must come to his bed when he so demands,[16]

- Hududpunishments for the religious crime ofzina(pre-marital, extra-marital sex) by free Muslims and non-Muslim slaves. It declared the punishment of flogging or stoning to death (Rajm), depending on the status of the accused i.e. Stoning for a Married (Muhsin) person (free or unfree), and as for the non-Muhsin, a free person will get one hundred stripes and a slave will get fifty if they self confess.[17]

Pillage and Slavery

[edit]- If two or more Muslims, or persons subject to Muslims, who enter a non-Muslim controlled territory (properties of non-combatants are excluded) for the purpose of pillage(seizing booties of the fighters) without the permission of the Imam, and thus seize some property of the inhabitants there, and bring it back into the Muslim territory, that property would be legally theirs.”[18]

Note: Plundering and pillaging of residential areas is forbidden in Islam[19][20]

- The right of Muslims to purchase and ownslaves.[21]

- A Muslim man's right to have sex with a captive slave girl he owns.[22]

- No inheritance rights for slaves.[23]

- The testimony of all slaves was inadmissible in a court of law.[24]

- Slaves require permission of the master before they can marry.[25]

- An unmarried Muslim may marry a slave girl owned by another but a Muslim married to a Muslim woman may not marry a slave girl.[26]

- Conditions under which the slaves may be emancipated partially or fully.[27]

Office of Censor

[edit]The Fatwa-e-Alamgiri also formalized the legal principle ofMuhtasib,or office of censor[28]that was already in use by previous rulers of theMughal Empire.[1]Any publication or information could be declared as heresy, and its transmission made a crime.[1]Officials (kotwal) were created to implement theShariadoctrine ofhisbah.[1]The offices and administrative structure created by Fatawa-e-Alamgiri aimed at Islamisation of South Asia.[1]

Development

[edit]The Fatawa-e-Alamgiri (also spelled Fatawa al-Alamgiriyya) was compiled in the late 1672, by 500 Muslim scholars fromMedina,Baghdadand in the Indian Subcontinent, inDelhi(India) andLahore(Pakistan), led by Sheikh Nizam Burhanpuri.[29][30]It was a creative application of Islamic law within theHanafifiqh.[1]It restricted the powers of Muslim judiciary and the Islamic jurists ability to issue discretionaryfatwas.[29][31]It is compiled in eight years between 1664-72. Ahmet Özel fromAtatürk Universityhas reported in his work onTDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi, el-alemgiriyye,that Fatawa-e-Alamgiri has spread fast toAnatoliaduring Aurangzeb rule due to the promotions of travellers, scholars, and officials.[32]

As the power shifted from Muslim rulers in India to theBritish,the colonial authorities decided to retain local institutions and laws, to operate under traditional pre-colonial laws instead of introducing secular European common law system.[2]Fatawa-i Alamgiri, as the documented Islamic law book, became the foundation of legal system of India during Aurangzeb and later Muslim rulers. Further, the English-speaking judges relied on Muslim law specialist elites to establish the law of the land, because the original Fatawa-i Alamgiri (Al-Hindiya) was written in Arabic. This created a social class of Islamic gentry that zealously guarded their expertise, legal authority and autonomy. It also led to inconsistent interpretation-driven, variegated judgments in similar legal cases, an issue that troubled British colonial officials.[2][33]

The assumption of the colonial government was that the presumed local traditional sharia-based law, as interpreted from Fatawa-i Alamgiri, could be implemented throughcommon law-style law institution with integrity.[2][34]However, this assumption unravelled in the 2nd half of the 19th century, because of inconsistencies and internal contradictions within Fatawa-i Alamgiri, as well as because the Aurangzeb-sponsored document was based on Hanafi Sunni sharia. Shia Muslims were in conflict with Sunni Muslims of South Asia, as were other minority sects of Islam, and they questioned the applicability of Fatawa-i Alamgiri.[2]Further, Hindus did not accept the Hanafi sharia-based code of law in Fatawa-i Alamgiri. Thirdly, the belief of the colonial government in "legal precedent" came into conflict with the disregard for "legal precedent" in the Anglo-Muhammadan legal system which emerged during theCompany period,leading colonial officials to distrust theMaulavis(Muslim religious scholars). The colonial administration responded by creating a bureaucracy that created separate laws for Muslim sects, and non-Muslims such as Hindus in South Asia.[2]This bureaucracy relied on Fatawa-i Alamgiri to formulate and enact a series of separate religious laws for Muslims and common laws for non-Muslims (Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, Sikhs), most of which were adopted in independent India after 1947.[34]

The British tried to sponsor translations of Fatawa-i Alamgiri. In the late 18th century, at the insistence of the British, the al-Hidaya was translated from Arabic to Persian. Charles Hamilton[35]and William Jones translated parts of the document along with other sharia-related documents in English. These translations triggered a decline in the power and role of theQadisin colonial India.[36]Neil Baillie published another translation, relying on Fatawa-i Alamgiri among other documents, in 1865, asA Digest of Mohummudan Law.[2][37]In 1873, Sircar published another English compilation of Muhammadan Law that included English translation of numerous sections of Fatawa-i Alamgiri.[38]These texts became the references that shaped law and jurisprudence in colonial India in late 19th and the first half of the 20th century, many of which continued in post-colonialIndia,PakistanandBangladesh.[2][34]

Contemporary comments

[edit]Burton Steinstates that the Fatawa-i-Alamgiri represented a re-establishment of Muslimulamaprominence in the political and administrative structure that had been previously lost by Muslim elites and people during Mughal EmperorAkbar's time. It reformulated legal principles to expand Islam and Muslim society by creating a new, expanded code of Islamic law.[39]

Some modern historians[40][41][42]have written that British efforts to translate and implement Sharia from documents such as the Fatawa-e Alamgiri had a lasting legal legacy during and in post-independence India (Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka).

According to Jamal Malik, the document stiffened the social stratification among Muslims and broke from the consensus of Hanafi Law.[43][44]He argues certain punishments reified the established categories: it introduced that Muslim nobles such asSayyidswere exempt from physical punishments,αthe governors and landholders could be humiliated but not arrested nor physically punished, the middle class could be humiliated and put into prison but not physically punished, while the lowest class commoners could be arrested, humiliated and physically punished.[45]The emperor was granted powers to issuefarmans(legal doctrine) that overruled fatwas of Islamic jurists.[29]

Mona Siddiquinotes that while the text is called afatawa,it is actually not a fatwa nor a collection of fatwas from Aurangzeb's time.[46]It is amabsūtsstyle,furu al-fiqh-genre Islamic text, one that compiles many statements and refers back to earlierHanafisharia texts as justification. The text considers contract not as a written document between two parties, but anoralagreement, in some cases such as marriage, one in the presence of witnesses.[46]

Translation

[edit]In 1892, Bengali scholarMuhammad Naimuddinpublished a four-volumeBengali languagetranslation of theFatawa ʿAlamgiriwith the assistance ofWajed Ali Khan Panniand the patronage of Hafez Mahmud Ali Khan Panni, theZamindarofKaratia.[47][48]Kafilur Rahman Nishat Usmani,a Deobandi jurist translated theFatawa 'Alamgiriinto Urdu language.[49]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^αHoweverHadd(scripturally proscribed) punishments applied to all subjects regardless of status and could not be modified by the Judge.[50]

Citations

[edit]- ^abcdefJamal Malik (2008), Islam in South Asia: A Short History, Brill Academic,ISBN978-9004168596,pp. 194-197

- ^abcdefghDavid Arnold and Peter Robb, Institutions and Ideologies: A SOAS South Asia Reader, Psychology Press, pp. 171-176

- ^The Cambridge History of India, Volume 5, Page 317

- ^The End of Muslim Rule in India, Volume 1, page 192-198

- ^Ahmad, Muhammad Basheer (1951).The Administration of Justice in Medieval India: A Study in Outline of the Judicial System Under the Sultans and the Badshahs of Delhi Based Mainly Upon Cases Decided by Medieval Courts in India Between 1206-1750 A.D.Manager of Publications. p. 42.

- ^The Administration of Justice in Medieval India,MB Ahmad, The Aligarh University (1941)

- ^Al-Bernhapuri, Nazarudeen. Fatawa Hindiyyah. 1st ed. Vol. 1. 6 vols. Damascus, Beirut, Kuwait: Dar an-Nawadir, 2013.

- ^Hussein, S M (2002).Structure of Politics Under Aurangzeb 1658-1707.Kanishka Publishers Distributors. p. 158.ISBN978-8173914898.

- ^Alan Guenther (2006), Hanafi Fiqh in Mughal India: The Fatawa-i Alamgiri, in Richard Eaton (Editor), India's Islamic Traditions: 711-1750, Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0195683349,pp. 209-230

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawp. 344 with footnote 1, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawpp. 515-546 with footnote 1 etc, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 6, pp. 632-637 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, pp. 402-403 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawp. 5 with footnote 1, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawpp. 392-400 with footnote 2 etc, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, p. 381 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawpp. 1-3 with footnotes, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawpp. 364 with footnote 3, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^https://www.iium.edu.my/deed/articles /hr/ch04.html

- ^https://www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2016/03/10/plundering-enemy-haram/

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 5, p. 273 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, pp. 395-397; Fatawa-i Alamgiri, Vol 1, pp. 86-88, Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 6, p. 631 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980);The Muhammadan Lawp. 275 annotations

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawpp. 371 with footnote 1, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, page 377 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980);The Muhammadan Lawp. 298 annotations

- ^Fatawa i-Alamgiri, Vol 1, pp. 394-398 - Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)

- ^A digest of the Moohummudan lawpp. 386 with footnote 1, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ^Regulation of MoralsMughal Administration, J Sircar

- ^abcM. Reza Pirbhai (2009), Reconsidering Islam in a South Asian Context, Brill Academic,ISBN978-9004177581,pp. 131-154

- ^Yamani, Mai; Allen, Andrew, eds. (1996).Feminism and Islam: legal and literary perspectives.New York: New York University Press.ISBN978-0-8147-9680-1.

- ^Jamal Malik (2008), Islam in South Asia: A Short History, Brill Academic,ISBN978-9004168596,pp. 192-199

- ^Sardella, Ferdinando; Jacobsen, Knut A., eds. (2020).Handbook of Hinduism in Europe (2 Vols).Brill. p. 1507.ISBN9789004432284.Retrieved25 April2024.

- ^K Ewing (1988), Sharia and ambiguity in South Asian Islam, University of California Press,ISBN978-0520055759

- ^abcJ. Duncan Derrett (1999), Religion, Law and State in India, Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0195647938

- ^Charles Hamilton,Guide: A Commentary on the Mussulman LawsatGoogle Books,Allen & Co, London

- ^U Yaduvansh (1969), The decline of the role of the qadis in India: 1793-1876, Studies in Islam, Vol 6, pp. 155-171

- ^A Digest of Moohummudan LawatGoogle Books,Smith Elder London, Harvard University Archives

- ^The Muhammadan LawatGoogle Books,(Translator: SC Sircar, Tagore Professor of Law, Calcutta, 1873)

- ^Burton Stein (2010), A History of India, John Wiley & Sons,ISBN978-1405195096,pp. 177-178

- ^Scott Kugle (2001),Framed, Blamed and Renamed: The Recasting of Islamic Jurisprudence in Colonial South Asia,Modern Asian Studies, Volume 35, Issue 02, pp 257-313

- ^Mona Siddiqui (1996), Law and the Desire for Social Control: An Insight into the Hanafi Concept of Kafa'a with Reference to the Fatawa 'Alamgiri, In Mai Yamani, ed. Feminism in Islam: Legal and Literary Perspectives,ISBN978-0814796818,New York University Press

- ^Daniel Collins (1987), Islamization of Pakistani Law: A Historical Perspective, Stanford Journal Int'l Law, Vol. 24, pp. 511-532

- ^Jamal Malik (2008), Islam in South Asia: A Short History, Brill Academic,ISBN978-9004168596,p. 195, Quote - "At the same time the Fatawa stiffened the social hierarchy of a highly stratified system at the head of which stood the emperor."

- ^Jamal Malik (2008), Islam in South Asia: A Short History, Brill Academic,ISBN978-9004168596,p. 195, Quote - "In some instances the Fatawa even disagreed with the consensual Hanafi law when it stipulated that rebels could be sentenced to death."

- ^Jamal Malik (2008), Islam in South Asia: A Short History, Brill Academic,ISBN978-9004168596,p. 195, Quote - "the noblest including ulama and sayyids (ulwiyya) were exempted from physical punishments, while governors (umara) and landholders (dahaqin) could be humiliated but not physically punished or imprisoned. The middle class (awsat) could not be physically punished but humiliated and imprisoned, while the lower classes (khasis and kamina) were subjected to all three categories of sentences: humiliation, physical punishment and imprisonment "

- ^abM Siddiqui (2012), The Good Muslim: Reflections on Classical Islamic Law and Theology, Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0521518642,pp 12-16

- ^Islam Khan, Nurul (1990).বাংলাদেশ জেলা গেজেটীয়ার টাংগাইল(in Bengali). Establishment Ministry. p. 277.

- ^Mir Shamsur Rahman (2012)."Panni, Wazed Ali Khan".InIslam, Sirajul;Miah, Sajahan;Khanam, Mahfuza;Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.).Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh(Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust,Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.ISBN984-32-0576-6.OCLC52727562.OL30677644M.Retrieved15 July2024.

- ^Qasmi, Amanat Ali (28 February 2018)."نستعلیق صفت انسان مفتی کفیل الرحمن نشاط عثمانی"[Well-Behaved Human: Mufti Kafeelur Rahman Nishat Usmani].Jahan-e-Urdu(in Urdu).Retrieved12 January2021.

- ^Hakeem, Farrukh B. "From Sharia to Mens rea: Legal transition to the Raj." International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 22, no. 2 (1998): 211-224.

Further reading

[edit]- The Muhammadan LawatGoogle Books,English translation of numerous sections of Fatawa i Alamgiri (Translator: SC Sircar, Tagore Professor of Law, Calcutta, 1873)

- Sheikh Nizam, al-Fatawa al-Hindiyya, 6 vols, Beirut: Dar Ihya' al-Turath al-'Arabi, 3rd Edition, (1980)