Arabic diacritics

This article needs editing tocomply with Wikipedia'sManual of Style.(June 2024) |

| Arabic alphabet |

|---|

|

Arabic script |

TheArabic scripthas numerousdiacritics,which include consonant pointing known asiʻjām(إِعْجَام), and supplementary diacritics known astashkīl(تَشْكِيل). The latter include the vowel marks termedḥarakāt(حَرَكَات;sg.حَرَكَة,ḥarakah).

The Arabic script is a modifiedabjad,where short consonants and long vowels are represented by letters but short vowels andconsonant lengthare not generally indicated in writing.Tashkīlis optional to represent missing vowels and consonant length. Modern Arabic is always written with thei‘jām—consonant pointing, but only religious texts, children's books and works for learners are written with the fulltashkīl—vowel guides and consonant length. It is however not uncommon for authors to add diacritics to a word or letter when the grammatical case or the meaning is deemed otherwise ambiguous. In addition, classical works and historic documents rendered to the general public are often rendered with the fulltashkīl,to compensate for the gap in understanding resulting from stylistic changes over the centuries.

Tashkīl

[edit]The literal meaning ofتَشْكِيلtashkīlis 'variation'. As the normal Arabic text does not provide enough information about the correct pronunciation, the main purpose oftashkīl(andḥarakāt) is to provide a phonetic guide or a phonetic aid; i.e. show the correct pronunciation for children who are learning to read or foreign learners.

The bulk of Arabic script is written withoutḥarakāt(or short vowels). However, they are commonly used in texts that demand strict adherence to exact pronunciation. This is true, primarily, of theQur'an⟨ٱلْقُرْآن⟩(al-Qurʾān) andpoetry.It is also quite common to addḥarakāttohadiths⟨ٱلْحَدِيث⟩(al-ḥadīth;plural:al-ḥādīth) and theBible.Another use is in children's literature. Moreover,ḥarakātare used in ordinary texts in individual words when an ambiguity of pronunciation cannot easily be resolved from context alone. Arabic dictionaries with vowel marks provide information about the correct pronunciation to both native and foreign Arabic speakers. In art andcalligraphy,ḥarakātmight be used simply because their writing is consideredaestheticallypleasing.

An example of a fullyvocalised(vowelisedorvowelled) Arabic from theBismillah:

بِسْمِ ٱللَّٰهِ ٱلرَّحْمَٰنِ ٱلرَّحِيمِ

bism Allāh al-Raḥmān al-Raḥīm

In the name of God, the All-Merciful, the Especially-Merciful.

Some Arabic textbooks for foreigners now useḥarakātas a phonetic guide to make learning reading Arabic easier. The other method used in textbooks is phoneticromanisationof unvocalised texts. Fully vocalised Arabic texts (i.e. Arabic texts withḥarakāt/diacritics) are sought after by learners of Arabic. Some online bilingual dictionaries also provideḥarakātas a phonetic guide similarly to English dictionaries providing transcription.

Harakat (short vowel marks)

[edit]Theḥarakātحَرَكَات,which literally means 'motions', are the short vowel marks. There is some ambiguity as to whichtashkīlare alsoḥarakāt;thetanwīn,for example, are markers for both vowels and consonants.

Fatḥah

[edit]Thefatḥah⟨فَتْحَة⟩is a small diagonal line placedabovea letter, and represents a short/a/(like the /a/ sound in the English word "cat" ). The wordfatḥahitself (فَتْحَة) meansopeningand refers to the opening of the mouth when producing an/a/.For example, withdāl(henceforth, the base consonant in the following examples):⟨دَ⟩/da/.

When afatḥahis placed before a plain letter⟨ا⟩(alif) (i.e. one having no hamza or vowel of its own), it represents a long/aː/(close to the sound of "a" in the English word "dad", with an open front vowel /æː/, not back /ɑː/ as in "father" ). For example:⟨دَا⟩/daː/.Thefatḥahis not usually written in such cases. When a fathah is placed before the letter ⟨ﻱ⟩ (yā’), it creates an/aj/(as in "lie"); and when placed before the letter ⟨و⟩ (wāw), it creates an/aw/(as in "cow").

Although paired with a plain letter creates an open front vowel (/a/), often realized as near-open (/æ/), the standard also allows for variations, especially under certain surrounding conditions. Usually, in order to have the more central (/ä/) or back (/ɑ/) pronunciation, the word features a nearby back consonant, such as the emphatics, as well asqāf,orrā’.A similar "back" quality is undergone by other vowels as well in the presence of such consonants, however not as drastically realized as in the case offatḥah.[1][2][3]

Kasrah

[edit]A similar diagonal linebelowa letter is called akasrah⟨كَسْرَة⟩and designates a short/i/(as in "me", "be" ) and its allophones [i, ɪ, e, e̞, ɛ] (as in "Tim", "sit" ). For example:⟨دِ⟩/di/.[4]

When akasrahis placed before a plain letter⟨ﻱ⟩(yā’), it represents a long/iː/(as in the English word "steed" ). For example:⟨دِي⟩/diː/.Thekasrahis usually not written in such cases, but ifyā’is pronounced as a diphthong/aj/,fatḥahshould be written on the preceding consonant to avoid mispronunciation. The wordkasrahmeans 'breaking'.[1]

Ḍammah

[edit]Theḍammah⟨ضَمَّة⟩is a small curl-like diacritic placed above a letter to represent a short /u/ (as in "duke", shorter "you" ) and its allophones [u, ʊ, o, o̞, ɔ] (as in "put", or "bull" ). For example:⟨دُ⟩/du/.[4]

When aḍammahis placed before a plain letter⟨و⟩(wāw), it represents a long/uː/(like the 'oo' sound in the English word "swoop" ). For example:⟨دُو⟩/duː/.Theḍammahis usually not written in such cases, but ifwāwis pronounced as a diphthong/aw/,fatḥahshould be written on the preceding consonant to avoid mispronunciation.[1]

The wordḍammah(ضَمَّة) in this context meansrounding,since it is the only rounded vowel in the vowel inventory of Arabic.

Alif Khanjariyah

[edit]Thesuperscript (or dagger)alif⟨أَلِف خَنْجَرِيَّة⟩(alif khanjarīyah), is written as short vertical stroke on top of a consonant. It indicates a long/aː/sound for whichalifis normally not written. For example:⟨هَٰذَا⟩(hādhā) or⟨رَحْمَٰن⟩(raḥmān).

The daggeralifoccurs in only a few words, but they include some common ones; it is seldom written, however, even in fully vocalised texts. Most keyboards do not have daggeralif.The wordAllah⟨الله⟩(Allāh) is usually produced automatically by enteringalif lām lām hāʾ.The word consists ofalif+ ligature of doubledlāmwith ashaddahand a daggeralifabovelām,followed byha'.

Maddah

[edit]Themaddah⟨مَدَّة⟩is atilde-shaped diacritic, which can only appear on top of analif(آ) and indicates aglottal stop/ʔ/followed by a long/aː/.

In theory, the same sequence/ʔaː/could also be represented by twoalifs, as in *⟨أَا⟩,where a hamza above the firstalifrepresents the/ʔ/while the secondalifrepresents the/aː/.However, consecutivealifs are never used in the Arabic orthography. Instead, this sequence must always be written as a singlealifwith amaddahabove it, the combination known as analif maddah.For example:⟨قُرْآن⟩/qurˈʔaːn/.

Alif waslah

[edit]Thewaṣlah⟨وَصْلَة⟩,alif waṣlah⟨أَلِف وَصْلَة⟩orhamzat waṣl⟨هَمْزَة وَصْل⟩looks like a small letterṣādon top of analif⟨ٱ⟩(also indicated by analif⟨ا⟩without ahamzah). It means that thealifis not pronounced when its word does not begin a sentence. For example:⟨بِٱسْمِ⟩(bismi), but⟨ٱمْشُوا۟⟩(imshūnotmshū). This is because no Arabic word can start with a vowel-less consonant: If the second letter from thewaṣlahhas a kasrah, the alif-waslah makes the sound /i/. However, when the second letter from it has a dammah, it makes the sound /u/.

It occurs only in the beginning of words, but it can occur after prepositions and the definite article. It is commonly found in imperative verbs, the perfective aspect of verb stems VII to X and theirverbal nouns(maṣdar). Thealifof the definite article is considered awaṣlah.

It occurs in phrases and sentences (connected speech, not isolated/dictionary forms):

- To replace the elided hamza whose alif-seat has assimilated to the previous vowel. For example:فِي ٱلْيَمَنorفي اليمن(fi l-Yaman) 'in Yemen'.

- In hamza-initial imperative forms following a vowel, especially following the conjunction⟨و⟩(wa-) 'and'. For example: َقُمْ وَٱشْرَبِ ٱلْمَاءَ(qum wa-shrab-i l-mā’) 'rise and then drink the water'.

Like the superscript alif, it is not written in fully vocalized scripts, except for sacred texts, like the Quran and Arabized Bible.

Sukūn

[edit]Thesukūn⟨سُكُونْ⟩is a circle-shaped diacritic placed above a letter (ْ). It indicates that the consonant to which it is attached is not followed by a vowel, i.e.,zero-vowel.

It is a necessary symbol for writing consonant-vowel-consonant syllables, which are very common in Arabic. For example:⟨دَدْ⟩(dad).

Thesukūnmay also be used to help represent a diphthong. Afatḥahfollowed by the letter⟨ﻱ⟩(yā’) with asukūnover it (ـَيْ) indicates the diphthongay(IPA/aj/). Afatḥah,followed by the letter⟨ﻭ⟩(wāw) with asukūn,(ـَوْ) indicates/aw/.

Thesukūnmay have also an alternative form of the small high head ofḥāʾ(U+06E1ۡARABIC SMALL HIGH DOTLESS HEAD OF KHAH), particularly in some Qurans. Other shapes may exist as well (for example, like a small comma above ⟨ʼ⟩ or like acircumflex⟨ˆ⟩ innastaʿlīq).[5]

Tanwin

[edit]The three vowel diacritics may be doubled at the end of a word to indicate that the vowel is followed by the consonantn.They may or may not be consideredḥarakātand are known astanwīn⟨تَنْوِين⟩,or nunation. The signs indicate, from left to right,-un, -in, -an.

These endings are used as non-pausal grammatical indefinite case endings inLiterary Arabicorclassical Arabic(triptotesonly). In a vocalised text, they may be written even if they are not pronounced (seepausa). Seei‘rābfor more details. In many spoken Arabic dialects, the endings are absent. Many Arabic textbooks introduce standard Arabic without these endings. The grammatical endings may not be written in some vocalized Arabic texts, as knowledge ofi‘rābvaries from country to country, and there is a trend towards simplifying Arabic grammar.

The sign⟨ـً⟩is most commonly written in combination with⟨ـًا⟩(alif),⟨ةً⟩(tā’ marbūṭah),⟨أً⟩(alif hamzah) or stand-alone⟨ءً⟩(hamzah).Alifshould always be written (except for words ending intā’ marbūṭah, hamzahor diptotes) even ifanis not. Grammatical cases andtanwīnendings in indefinite triptote forms:

- -un:nominative case;

- -an:accusative case,also serves as an adverbial marker;

- -in:genitive case.

Shaddah

[edit]Theshaddaorshaddah⟨شَدَّة⟩(shaddah), ortashdid⟨تَشْدِيد⟩(tashdīd), is a diacritic shaped like a small written Latin "w".

It is used to indicategemination(consonant doubling or extra length), which is phonemic in Arabic. It is written above the consonant which is to be doubled. It is the onlyḥarakahthat is commonly used in ordinary spelling to avoidambiguity.For example:⟨دّ⟩/dd/;madrasah⟨مَدْرَسَة⟩('school') vs.mudarrisah⟨مُدَرِّسَة⟩('teacher', female).

I‘jām

[edit]

Thei‘jām(إِعْجَام;sometimes also callednuqaṭ)[6]are the diacritic points that distinguish various consonants that have the same form (rasm), such as⟨ص⟩/sˤ/,⟨ض⟩/dˤ/.Typicallyi‘jāmare not considered diacritics but part of the letter.

Early manuscripts of theQurandid not use diacritics either for vowels or to distinguish the different values of therasm.Vowel pointing was introduced first, as a red dot placed above, below, or beside therasm,and later consonant pointing was introduced, as thin, short black single or multiple dashes placed above or below therasm.Thesei‘jāmbecame black dots about the same time as theḥarakātbecame small black letters or strokes.

Typically, Egyptians do not use dots under finalyā’(ي), which looks exactly likealif maqṣūrah(ى) in handwriting and in print. This practice is also used in copies of themuṣḥaf(Qurʾān) scribed by‘Uthman Ṭāhā.The same unification ofyāandalif maqṣūrāhas happened inPersian,resulting in whatthe Unicode Standardcalls "Arabic Letter Farsi Yeh",that looks exactly the same asyāin initial and medial forms, but exactly the same asalif maqṣūrahin final and isolated forms.

At the time when thei‘jāmwas optional, unpointed letters were ambiguous. To clarify that a letter would lacki‘jāmin pointed text, the letter could be marked with a small v- orseagull-shaped diacritic above, also a superscript semicircle (crescent), a subscript dot (except in the case of⟨ح⟩;three dots were used with⟨س⟩), or a subscript miniature of the letter itself. A superscript stroke known asjarrah,resembling a longfatħah,was used for a contracted (assimilated)sin.Thus⟨ڛ سۣ سۡ سٚ⟩were all used to indicate that the letter in question was truly⟨س⟩and not⟨ش⟩.[7]These signs, collectively known as‘alāmātu-l-ihmāl,are still occasionally used in modernArabic calligraphy,either for their original purpose (i.e. marking letters withouti‘jām), or often as purely decorative space-fillers. The smallکabove thekāfin its final and isolated forms⟨ك ـك⟩was originally an‘alāmatu-l-ihmālthat became a permanent part of the letter. Previously this sign could also appear above the medial form ofkāf,when that letter was written without the stroke on itsascender.Whenkafwas written without that stroke, it could be mistaken forlam,thuskafwas distinguished with a superscriptkafor a small superscripthamza(nabrah), andlamwith a superscriptl-a-m(lam-alif-mim).[8]

Hamza

[edit]

Although normally it is sometimes not considered a letter of the alphabet, thehamzaهَمْزة(hamzah,glottal stop), often stands as a separate letter in writing, is written in unpointed texts and is not considered atashkīl.It may appear as a letter by itself or as a diacritic over or under analif,wāw,oryā.

Which letter is to be used to support thehamzahdepends on the quality of the adjacent vowels;

- If the glottal stop occurs at the beginning of the word, it is always indicated by hamza on analif:above if the following vowel is/a/or/u/and below if it is/i/.

- If the glottal stop occurs in the middle of the word,hamzahabovealifis used only if it is not preceded or followed by/i/or/u/:

- If the glottal stop occurs at the end of the word (ignoring any grammatical suffixes), if it follows a short vowel it is written abovealif,wāw,oryāthe same as for a medial case; otherwise on the line (i.e. if it follows a long vowel, diphthong or consonant).

- Twoalifs in succession are never allowed:/ʔaː/is written withalif maddah⟨آ⟩and/aːʔ/is written with a freehamzahon the line⟨اء⟩.

Consider the following words:⟨أَخ⟩/ʔax/( "brother" ),⟨إسْماعِيل⟩/ʔismaːʕiːl/( "Ismael" ),⟨أُمّ⟩/ʔumm/( "mother" ). All three of above words "begin" with a vowel opening the syllable, and in each case,alifis used to designate the initial glottal stop (theactualbeginning). But if we considermiddlesyllables "beginning" with a vowel:⟨نَشْأة⟩/naʃʔa/( "origin" ),⟨أَفْئِدة⟩/ʔafʔida/( "hearts" —notice the/ʔi/syllable; singular⟨فُؤاد⟩/fuʔaːd/),⟨رُؤُوس⟩/ruʔuːs/( "heads", singular⟨رَأْس⟩/raʔs/), the situation is different, as noted above. See the comprehensive article onhamzahfor more details.

Diacritics not used in Modern Standard Arabic

[edit]Diacritics not used in Modern Standard Arabic but in other languages that use the Arabic script, and sometimes to write Arabic dialects, include (the list is not exhaustive):

| Description | Unicode | Example | Language(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bars and lines | ||||

| diagonal bar above | گ | Arabic (Iraq),Balti,Burushaski, Kashmiri,Kazakh, Khowar,Kurdish, Kyrgyz,Persian, Sindhi,Urdu, Uyghur |

||

| horizontal bar above | Pashto | |||

| vertical line above | ئۈ | Uyghur |

| |

| Dots | ||||

| 2 dots (vertical) | ݭݙ | |||

| 4 dots | ڐ ٿ ڐ ڙ | Sindhi, Old Hindustani | ||

| dot below | U+065CٜARABIC VOWEL SIGN DOT BELOW | ٜ بٜ | African languages[10] |

|

| Variants of standard Arabic diacritics | ||||

| wavy hamza | ٲ اٟ | Kashmiri |

| |

| curly kasra above | ◌ࣥ | Rohingya |

| |

| Rohingya |

| |||

| double kasra above | ◌ࣱ | Rohingya |

| |

| inverted and regular curly kasras above | ◌ࣨ | Rohingya |

| |

| Tildes | ||||

| diagonal tilde shape above | ◌ࣤ | Rohingya |

| |

| diagonal tilde shape below | ◌ࣦ | Rohingya |

| |

| Arabic letters | ||||

| miniature Arabic letter hah (initial form) ﺣ above | ◌ۡ | Rohingya |

| |

| miniature Arabic letter tah ط above | ݲ | Urdu | ||

| Eastern Arabic numerals[13] | ||||

| Eastern Arabic numeral 2: ٢ above | U+0775,U+0778,U+077A | ݵݸݺ | Burushaski |

|

| Eastern Arabic numeral 3: ٣ above | U+0776,U+0779,U+077B | ݶݹݻ | Burushaski |

|

| Urdu number4: ۴ above or below | U+0777,U+077C,U+077D | ݷݼݽ | Burushaski |

|

| Shapes like Latin letters | ||||

| Nūn ġuṇnā,"u" shape above | ن٘ | Urdu |

| |

| "v" shape above | ۆ ؤیٛ | Azerbaijani | ||

| invered "v" shape above | ئۆ | Azerbaijani,Uyghur | ||

| dotted fatha | ◌ࣵ | Wolof | Latin à | |

| circle with fatha | ◌ࣴ | Wolof | Latin ë | |

| less than sign - below | ◌ࣹ | Wolof | Latin e | |

| greater than sign - below | ◌ࣺ | Wolof | Latin é | |

| less than sign - above | ◌ࣷ | Wolof | Latin o | |

| greater than sign - above | ◌ࣸ | Wolof | Latin ó | |

| ring | ګ | Pashto |

| |

| Other shapes | ||||

| "fish" shape above | دࣤ࣬ دࣥ࣬ دࣦ࣯ | Rohingya | Ṭāna,e.g.دࣤ࣬ / دࣥ࣬ / دࣦ࣯ written above or below other diacritics to mark along rising tone(/˨˦/).[14][15] | |

| Various | Urdu |

| ||

Rohingya tone markers

[edit]Historically Arabic script has been adopted and used by many tonal languages, examples includeXiao'erjingforMandarin Chineseas well asAjami scriptadopted for writing various languages of Western Africa. However, the Arabic script never had an inherent way of representing tones until it was adapted for theRohingya language.TheRohingya Fonnaare 3 tone markers which are part of the standardized and accepted orthographic convention of Rohingya. It remains the only known instance of tone markers within theArabic script.[14][15]

Tone markers act as "modifiers" of vowel diacritics. In simpler words, they are "diacritics for the diacritics". They are written "outside" of the word, meaning that they are written above the vowel diacritic if the diacritic is written above the word, and they are written below the diacritic if the diacritic is written below the word. They are only ever written where there are vowel diacritics. This is important to note, as without the diacritic present, there is no way to distinguish between tone markers andI‘jāmi.e. dots that are used for purpose of phonetic distinctions of consonants.

Hārbāy

TheHārbāyas it is called in Rohingya, is a single dot that's placed on top ofFatḥahandḌammah,orcurly Fatḥahandcurly Ḍammah(vowel diacritics unique to Rohinghya), or their respectiveFatḥatanandḌammatanversions, and it's placed underneathKasrahorcurly Kasrah,or their respectiveKasratanversion. (e.g.دً࣪ / دٌ࣪ / دࣨ࣪ / دٍ࣭) This tone marker indicates ashort high tone(/˥/).[14][15]

Ṭelā

TheṬelāas it is called in Rohingya, is two dots that are placed on top ofFatḥahandḌammah,orcurly Fatḥahandcurly Ḍammah,or their respectiveFatḥatanandḌammatanversions, and it's placed underneathKasrahorcurly Kasrah,or their respectiveKasratanversion. (e.g.دَ࣫ / دُ࣫ / دِ࣮) This tone marker indicates along falling tone(/˥˩/).[14][15]

Ṭāna

TheṬānaas it is called in Rohingya, is a fish-like looping line that is placed on top ofFatḥahandḌammah,orcurly Fatḥahandcurly Ḍammah,or their respectiveFatḥatanandḌammatanversions, and it's placed underneathKasrahorcurly Kasrah,or their respectiveKasratanversion. (e.g.دࣤ࣬ / دࣥ࣬ / دࣦ࣯) This tone marker indicates along rising tone(/˨˦/).[14][15]

History

[edit]

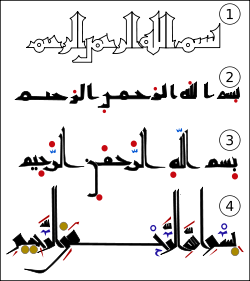

(1) Early 9th century, script with no dots or diacritic marks (seeimage of early Basmala Kufic);

(2) and (3) 9th–10th century under Abbasid dynasty, Abu al-Aswad's system established red dots with each arrangement or position indicating a different short vowel; later, a second black-dot system was used to differentiate between letters likefā’andqāf;

(4) 11th century, in al-Farāhídi's system (system we know today) dots were changed into shapes resembling the letters to transcribe the corresponding long vowels.

According to tradition, the first to commission a system ofharakatwasAliwho appointedAbu al-Aswad al-Du'alifor the task. Abu al-Aswad devised a system of dots to signal the three short vowels (along with their respective allophones) of Arabic. This system of dots predates thei‘jām,dots used to distinguish between different consonants.

-

Early Basmala Kufic

-

Middle Kufic

-

Modern Kufic in Qur'an

Abu al-Aswad's system

[edit]Abu al-Aswad's system of Harakat was different from the system we know today. The system used red dots with each arrangement or position indicating a different short vowel.

A dot above a letter indicated the vowela,a dot below indicated the voweli,a dot on the side of a letter stood for the vowelu,and two dots stood for thetanwīn.

However, the early manuscripts of the Qur'an did not use the vowel signs for every letter requiring them, but only for letters where they were necessary for a correct reading.

Al Farahidi's system

[edit]The precursor to the system we know today is Al Farahidi's system.al-Farāhīdīfound that the task of writing using two different colours was tedious and impractical. Another complication was that thei‘jāmhad been introduced by then, which, while they were short strokes rather than the round dots seen today, meant that without a color distinction the two could become confused.

Accordingly, he replaced theḥarakātwith small superscript letters: small alif, yā’, and wāw for the short vowels corresponding to the long vowels written with those letters, a smalls(h)īnforshaddah(geminate), a smallkhā’forkhafīf(short consonant; no longer used). His system is essentially the one we know today.[17]

Automatic diacritization

[edit]The process of automatically restoring diacritical marks is called diacritization or diacritic restoration. It is useful to avoid ambiguity in applications such asArabic machine translation,text-to-speech,andinformation retrieval.Automatic diacritization algorithms have been developed.[18][19]ForModern Standard Arabic,thestate-of-the-artalgorithm has aword error rate(WER) of 4.79%. The most common mistakes are propernounsandcase endings.[20]Similar algorithms exist for othervarieties of Arabic.[21]

See also

[edit]- Arabic alphabet:

- Hebrew:

- Hebrew diacritics,the Hebrew equivalent

- Niqqud,the Hebrew equivalent ofḥarakāt

- Dagesh,the Hebrew diacritic similar to Arabici‘jāmand shaddah

References

[edit]- ^abcKarin C. Ryding, "A Reference Grammar of Modern Standard Arabic", Cambridge University Press, 2005, pgs. 25-34, specifically “Chapter 2, Section 4: Vowels”

- ^Anatole Lyovin, Brett Kessler, William Ronald Leben, "An Introduction to the Languages of the World", "5.6 Sketch of Modern Standard Arabic", Oxford University Press, 2017, pg. 255, Edition 2, specifically “5.6.2.2 Vowels”

- ^Amine Bouchentouf, Arabic For Dummies®, John Wiley & Sons, 2018, 3rd Edition, specifically section "All About Vowels"

- ^ab"Introduction to Written Arabic".University of Victoria, Canada.

- ^"Arabic character notes".r12a.

- ^Ibn Warraq(2002). Ibn Warraq (ed.).What the Koran Really Says: Language, Text & Commentary.Translated by Ibn Warraq. New York: Prometheus. p. 64.ISBN1-57392-945-X.Archived fromthe originalon 11 April 2019.Retrieved9 April2019.

- ^Gacek, Adam (2009)."Unpointed letters".Arabic Manuscripts: A Vademecum for Readers.BRILL. p. 286.ISBN978-90-04-17036-0.

- ^Gacek, Adam (1989)."Technical Practices and Recommendations Recorded by Classical and Post-Classical Arabic Scholars Concerning the Copying and Correction of Manuscripts"(PDF).InDéroche, François(ed.).Les manuscrits du Moyen-Orient: essais de codicologie et de paléographie. Actes du colloque d'Istanbul (Istanbul 26–29 mai 1986).p. 57 (§ 8. Diacritical marks and vowelisation).

- ^Alkalesi, Yasin M. (2001) "Modern iraqi arabic: A textbook". Georgetown University Press.ISBN978-0878407880

- ^ab"Arabic Range: 0600–06FF The Unicode Standard, Version 15.1"(PDF).Unicode.Retrieved10 July2024.

- ^"Vowel 04: ٲ / ä – (aae)".Kashmiri Dictionary.31 January 2021.Retrieved11 July2024.

- ^"Vowel07: اٟ / ü ( ι )".Kashmiri Dictionary.6 February 2021.Retrieved11 July2024.

- ^Mirza, Umair (2006).بروشسکی اردو لغت[Burushaski–Urdu Dictionary] (in Urdu and Burushaski). pp. 28–29.ISBN969-404-66-0.Retrieved13 July2024.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^abcdePriest, Lorna A.; Hosken, Martin (10 August 2010)."Proposal to add Arabic script characters for African and Asian languages"(PDF).The Unicode Consortium.Archived(PDF)from the original on 8 October 2022.Retrieved5 May2023.

- ^abcdePandey, Anshuman (27 October 2015)."Proposal to encode the Hanifi Rohingya script in Unicode"(PDF).The Unicode Consortium.Archived(PDF)from the original on 12 December 2019.Retrieved5 May2023.

- ^"Proposal of Inclusion of Certain Characters in Unicode"(PDF).

- ^Versteegh, C. H. M. (1997).The Arabic Language.Columbia University Press. pp. 56ff.ISBN978-0-231-11152-2.

- ^Azmi, Aqil M.; Almajed, Reham S. (2013-10-10)."A survey of automatic Arabic diacritization techniques".Natural Language Engineering.21(3): 477–495.doi:10.1017/S1351324913000284.ISSN1351-3249.S2CID31560671.

- ^Almanea, Manar (2021)."Automatic Methods and Neural Networks in Arabic Texts Diacritization: A Comprehensive Survey".IEEE Access.9:145012–145032.Bibcode:2021IEEEA...9n5012A.doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3122977.ISSN2169-3536.S2CID240011970.

- ^Thompson, Brian; Alshehri, Ali (2021-09-28). "Improving Arabic Diacritization by Learning to Diacritize and Translate".arXiv:2109.14150[cs.CL].

- ^Masmoudi, Abir; Aloulou, Chafik; Abdellahi, Abdel Ghader Sidi; Belguith, Lamia Hadrich (2021-08-08)."Automatic diacritization of Tunisian dialect text using SMT model".International Journal of Speech Technology.25:89–104.doi:10.1007/s10772-021-09864-6.ISSN1572-8110.S2CID238782966.