Fertile Crescent

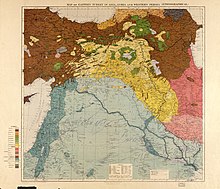

TheFertile Crescent(Arabic:الهلال الخصيب) is a crescent-shaped region in theMiddle East,spanning modern-dayIraq,Israel,Jordan,Lebanon,Palestine,andSyria,together with northernKuwait,south-easternTurkey,and westernIran.[1][2]Some authors also includeCyprusand northernEgypt.[3][4]

The Fertile Crescent is believed to be the first region wheresettled farmingemerged as people started the process of clearance and modification of natural vegetation to grow newly domesticated plants ascrops.Early humancivilizationssuch asSumerinMesopotamiaflourished as a result.[5]Technological advances in the region include the development ofagricultureand the use ofirrigation,ofwriting,thewheel,andglass,most emerging first inMesopotamia.

Terminology

The term "Fertile Crescent" was popularized byarchaeologistJames Henry BreastedinOutlines of European History(1914) andAncient Times, A History of the Early World(1916).[6][7][8][9][10][11]He wrote:[6]

It lies like an army facing south, with one wing stretching along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean and the other reaching out to the Persian Gulf, while the center has its back against the northern mountains. The end of the western wing is Palestine; Assyria makes up a large part of the center; while the end of the eastern wing is Babylonia. [...] This great semicircle, for lack of a name, may be called the Fertile Crescent.

There is no single term for this region in antiquity. At the time that Breasted was writing, it roughly corresponded with the territories of theOttoman Empireceded to Britain and France in theSykes–Picot Agreement.Historian Thomas Scheffler has noted that Breasted was following a trend in Western geography to "overwrite the classical geographical distinctions between continents, countries and landscapes with large, abstract spaces", drawing parallels with the work ofHalford Mackinder,who conceptualised Eurasia as a 'pivot area' surrounded by an 'inner crescent',Alfred Thayer Mahan'sMiddle East,andFriedrich Naumann'sMitteleuropa.[12]

In current usage, the Fertile Crescent includesIsrael,Palestine,Iraq,Syria,Lebanon,Egypt,andJordan,as well as the surrounding portions ofTurkeyandIran.In addition to theTigrisandEuphrates,riverwater sources include theJordan River.The inner boundary is delimited by the dry climate of theSyrian Desertto the south. Around the outer boundary are theAnatolianandArmenian highlandsto the north, theSahara Desertto the west,Sudanto the south, and theIranian plateauto the east.[citation needed]

Biodiversity and climate

As crucial as rivers andmarshlandswere to therise of civilizationin the Fertile Crescent, they were not the only factor. The area is geographically important as the "bridge" betweenNorth AfricaandEurasia,which has allowed it to retain a greater amount ofbiodiversitythan eitherEuropeorNorth Africa,whereclimate changesduring theIce Ageled to repeatedextinctionevents when ecosystems became squeezed against the waters of theMediterranean Sea.TheSaharan pump theoryposits that this Middle Easternland bridgewas extremely important to the modern distribution ofOld Worldfloraandfauna,including thespread of humanity.[citation needed]

The area has borne the brunt of thetectonic divergencebetween the African and Arabianplatesand the converging Arabian and Eurasian plates, which has made the region a very diverse zone of high snow-covered mountains.[citation needed]

The Fertile Crescent had many diverseclimates,and major climatic changes encouraged the evolution of many"r" typeannual plants,which produce more edible seeds than"K" typeperennial plants.The region's dramatic variety in elevation gave rise to many species of edible plants for early experiments in cultivation. Most importantly, the Fertile Crescent was home to the eightNeolithic founder cropsimportant in earlyagriculture(i.e., wild progenitors toemmer wheat,einkorn,barley,flax,chick pea,pea,lentil,bitter vetch), and four of the five most important species ofdomesticatedanimals—cows,goats,sheep,andpigs;the fifth species, thehorse,lived nearby.[13]The Fertile Crescent flora comprises a high percentage of plants that canself-pollinate,but may also becross-pollinated.[13]These plants, called "selfers",were one of the geographical advantages of the area because they did not depend on other plants for reproduction.[13]

History

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(June 2021) |

As well as possessing many sites with the skeletal and cultural remains of both pre-modern and earlymodern humans(e.g., atTabunandEs Skhulcaves), laterPleistocenehunter-gatherers,andEpipalaeolithicsemi-sedentary hunter-gatherers (theNatufians); the Fertile Crescent is most famous for its sites related to theorigins of agriculture.The western zone around the Jordan and upper Euphrates rivers gave rise to the first knownNeolithicfarmingsettlements (referred to asPre-Pottery Neolithic A(PPNA)), which date to around 9,000 BCE and includes very ancient sites such asGöbekli Tepe,Chogha Golan,andJericho (Tell es-Sultan).

This region, alongsideMesopotamia(Greek for "between rivers", between the riversTigrisandEuphrates,lies in the east of the Fertile Crescent), also saw the emergence of earlycomplex societiesduring the succeedingBronze Age.There is also early evidence from the region forwritingand the formation ofhierarchicalstate levelsocieties. This has earned the region the nickname "Thecradle of civilization".

It is in this region where the firstlibrariesappeared about 4,500 years ago. The oldest known libraries are found inNippur(in Sumer) andEbla(in Syria), both fromc. 2500 BCE.[14]

Both the Tigris and Euphrates start in theTaurus Mountainsof what is modern-dayTurkey.Farmers in southern Mesopotamia had to protect their fields from flooding each year. Northern Mesopotamia had sufficient rain to make some farming possible. To protect against flooding they made levees.[15]

Since theBronze Age,the region's naturalfertilityhas been greatly extended byirrigationworks, upon which much of its agricultural production continues to depend. The last two millennia have seen repeated cycles of decline and recovery as past works have fallen into disrepair through the replacement of states, to be replaced under their successors. Another ongoing problem has beensalination—gradual concentration of salt and other minerals in soils with a long history of irrigation.

Early domestications

Prehistoric seedlessfigswere discovered atGilgal Iin theJordan Valley,suggesting that fig trees were being planted some 11,400 years ago.[16]Cerealswere already grown inSyriaas long as 9,000 years ago.[17]Small cats (Felis silvestris) also were domesticated in this region.[18]Also,legumesincludingpeas,lentilsandchickpeawere domesticated in this region.

Domesticated animalsinclude thecattle,sheep,goat,domestic pig,cat,anddomestic goose.

Cosmopolitan diffusion

| Theancient Near East |

|---|

|

Modern analyses[19][20]comparing 24 craniofacial measurements reveal a relatively diverse population within the pre-Neolithic,NeolithicandBronze AgeFertile Crescent,[19]supporting the view that several populations occupied this region during these time periods.[19][21][22][23][24][25][26]Similar arguments do not hold true for theBasquesandCanary Islandersof the same time period, as the studies demonstrate those ancient peoples to be "clearly associated with modern Europeans". Additionally, no evidence from the studies demonstratesCro-Magnoninfluence, contrary to former suggestions.[19]

The studies further suggest adiffusionof this diverse population away from the Fertile Crescent, with the early migrants moving away from theNear East—westward intoEuropeandNorth Africa,northward toCrimea,and northeastward toMongolia.[19]They took their agricultural practices with them and interbred with thehunter-gathererswhom they subsequently came in contact with while perpetuating their farming practices. This supports priorgenetic[27][28][29][30][31]andarchaeological[19][32][33][34][35][36]studies which have all arrived at the same conclusion.

Consequently, contemporaryin situpeoples absorbed the agricultural way of life of those early migrants who ventured out of the Fertile Crescent. This is contrary to the suggestion that the spread of agriculture disseminated out of the Fertile Crescent by way of sharing of knowledge. Instead, the view now supported by a preponderance of evidence is that it occurred by actual migration out of the region, coupled with subsequent interbreeding with indigenous local populations whom the migrants came in contact with.[19]

The studies show also that not all present dayEuropeansshare strong genetic affinities to theNeolithicandBronze Ageinhabitants of the Fertile Crescent; the closest ties to the Fertile Crescent rest with Southern Europeans. The same study further demonstrates all present-dayEuropeansto be closely related.[19]

Languages

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(June 2021) |

Linguistically, the Fertile Crescent was a region of great diversity. Historically,Semitic languagesgenerally prevailed in the modern regions ofIraq,Syria,Jordan,Lebanon,Israel,Palestine,Sinaiand the fringes of southeastTurkeyand northwestIran,as well as theSumerian(alanguage isolate) in Iraq, whilst in the mountainous areas to the east and north a number of generally unrelatedlanguage isolateswere found, including;Elamite,GutianandKassiteinIran,andHattic,KaskianandHurro-Urartianin Turkey. The precise affiliation of these, and their date of arrival, remain topics of scholarly discussion. However, given lack of textual evidence for the earliest era of prehistory, this debate is unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

The evidence that does exist suggests that, by the third millennium BCE and into the second, several language groups already existed in the region. These included:[37][38][39][40][41][42]

- Proto-Euphratean language:a hypothetical non-Semitic language previously hypothesized to be thesubstratumlanguage of the people that introduced farming into SouthernIraqin the EarlyUbaid period.(5300–4700 BCE) The linguistic consensus today is that multiple unknown substrata contributed to the formation of the artifacts in Sumerian names that motivated the Proto-Euphratean substrate hypothesis, including fossilized archaic elements from earlier stages of Sumerian itself.[43]

- Sumerian:a non-Semiticlanguage isolatethat displays aSprachbund-type relationship with neighbouring Semitic Akkadian

- Elamite language:a non-Semiticlanguage isolate

- Semitic languages:Akkadian(akaAssyrianandBabylonian),Eblaite,Amorite,Aramaic,Ugaritic,Canaanite languages(includingHebrew,Moabite,Edomite,Phoenician/Carthaginian)

- Hattic:alanguage isolate,spoken originally incentral Anatolia

- Indo-European languages:generally believed to be later intrusive languages arriving after 2000 BCE, such asHittite,Luwianand theIndo-Aryanmaterial attested in theMitannicivilization, but recent evidence suggests that the language family emerged from the Fertile Crescent as early as 6000 BCE[44]

- Egyptian:a stand-alone branch of theAfroasiatic languagesconfined toEgypt

- Hurro-Urartian languages,a small family. TheKassite languagespoken in the northern part of the region may have belonged to this family.

Links between Hurro-Urartian and Hattic and the indigenous languages of the Caucasus have frequently been suggested, but are not generally accepted.

See also

- Beth Nahrain– Areas between and surrounding the Euphrates and Tigris rivers

- Hilly Flanks– Area around the Fertile Crescent of Southwest Asia

- History of agriculture

- History of Mesopotamia

- Hydraulic empire– Government by control of access to water

- Fertile Crescent Plan

- Syria (region)

References

- ^Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana; McBride, Bunny (13 January 2013).The Essence of Anthropology(3rd ed.). Belmont, California:Cengage Learning.p. 104.ISBN978-1111833442.

- ^Ancient Mesopotamia/India.Culver City, California: Social Studies School Service. 2003. p. 4.ISBN978-1560041665.

- ^"Countries in the Fertile Crescent 2024".

- ^Quam, Joel; Campbell, Scott (31 August 2022)."North Africa & the Middle East: Regional Example – The Fertile Crescent".

- ^The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica."Fertile Crescent".Encyclopædia Britannica.Cambridge University Press.Retrieved28 January2018.

- ^abAbt, Jeffrey (2011).American Egyptologist: the life of James Henry Breasted and the creation of his Oriental Institute.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 193–194, 436.ISBN978-0-226-0011-04.

- ^Goodspeed, George Stephen (1904).A History of the ancient world: for high schools and academies.New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp.5–6.

- ^Breasted, James Henry (1914)."Earliest man, the Orient, Greece, and Rome"(PDF).In Robinson, James Harvey; Breasted, James Henry; Beard, Charles A. (eds.).Outlines of European history, Vol. 1.Boston: Ginn. pp. 56–57.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2022-10-09."The Ancient Orient" map is inserted between pages 56 and 57.

- ^Breasted, James Henry (1916).Ancient times, a history of the early world: an introduction to the study of ancient history and the career of early man(PDF).Boston: Ginn. pp. 100–101.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2022-10-09."The Ancient Oriental World" map is inserted between pages 100 and 101.

- ^Clay, Albert T. (1924). "The so-called Fertile Crescent and desert bay".Journal of the American Oriental Society.44:186–201.doi:10.2307/593554.ISSN0003-0279.JSTOR593554.

- ^Kuklick, Bruce (1996)."Essay on methods and sources".Puritans in Babylon: the ancient Near East and American intellectual life, 1880–1930.Princeton: Princeton University Press. p.241.ISBN978-0-691-02582-7.

Textbooks...The true texts brought all of these strands together, the most important being James Henry Breasted,Ancient Times: A History of the Early World(Boston, 1916), but a predecessor, George Stephen Goodspeed,A History of the Ancient World(New York, 1904), is outstanding. Goodspeed, who taught at Chicago with Breasted, antedated him in the conception of a 'crescent' of civilization.

- ^Scheffler, Thomas (2003-06-01)."'Fertile Crescent', 'Orient', 'Middle East': The Changing Mental Maps of Southwest Asia ".European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire.10(2): 253–272.doi:10.1080/1350748032000140796.ISSN1350-7486.S2CID6707201.

- ^abcDiamond, Jared(March 1997).Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies(1st ed.).W.W. Norton & Company.p. 480.ISBN978-0-393-03891-0.OCLC35792200.

- ^Murray, Stuart (9 July 2009). Basbanes, Nicholas A.; Davis, Donald G. (eds.).A Review of "The Library: An Illustrated History": Murray, Stuart A.P.New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2009, 310 pp., $35.00, hard cover, ISBN 978-1602397064..Vol. 15. New York, NY:Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.pp. 69–70.doi:10.1080/10875300903535149.ISBN9781628733228.OCLC277203534.S2CID61069680.

- ^Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999).World History: Patterns of Interaction.Evanston, IL:McDougal Littell.p.1082.ISBN978-0-395-87274-1.

- ^Norris, Scott (1 June 2006)."Ancient Fig Find May Push Back Birth of Agriculture".National Geographic Society.National Geographic News.Archived fromthe originalon June 2, 2006.Retrieved6 March2017.

- ^"Genographic Project: The Development of Agriculture".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon June 5, 2013.Retrieved14 April2016.

- ^Driscoll, Carlos A.; Menotti-Raymond, Marilyn; Roca, Alfred L.; Hupe, Karsten; Johnson, Warren E.; Geffen, Eli; Harley, Eric H.; Delibes, Miguel; Pontier, Dominique; Kitchener, Andrew C.; Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki;O'Brien, Stephen J.;Macdonald, David W.(27 July 2007)."The near eastern origin of cat domestication".Science.317(5837): 519–523.Bibcode:2007Sci...317..519D.doi:10.1126/science.1139518.PMC5612713.PMID17600185.

- ^abcdefghBrace, C. Loring; Seguchi, Noriko; Quintyn, Conrad B.; Fox, Sherry C.; Nelson, A. Russell; Manolis, Sotiris K.; Qifeng, Pan (2006)."The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA.103(1): 242–247.Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B.doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102.PMC1325007.PMID16371462.

- ^Ricaut, F. X.; Waelkens, M. (Aug 2008). "Cranial Discrete Traits in a Byzantine Population and Eastern Mediterranean Population Movements".Human Biology.80(5): 535–564.doi:10.3378/1534-6617-80.5.535.PMID19341322.S2CID25142338.

- ^Lazaridis, Iosif; Nadel, Dani; Rollefson, Gary; Merrett, Deborah C.; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Fernandes, Daniel; Novak, Mario; Gamarra, Beatriz; Sirak, Kendra; Connell, Sarah; Stewardson, Kristin; Harney, Eadaoin; Fu, Qiaomei; Gonzalez-Fortes, Gloria (2016-08-25)."Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East".Nature.536(7617): 419–424.Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L.doi:10.1038/nature19310.PMC5003663.PMID27459054.

- ^Barker, G. (2002). Bellwood, P.; Renfrew, C. (eds.).Transitions to farming and pastoralism in North Africa.pp. 151–161.

- ^Bar-Yosef O (1987), "Pleistocene connections between Africa and SouthWest Asia: an archaeological perspective",The African Archaeological Review;Chapter 5, pp 29–38

- ^Kislev, ME; Hartmann, A; Bar-Yosef, O (2006). "Early domesticated fig in the Jordan Valley".Science.312(5778): 1372–1374.Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1372K.doi:10.1126/science.1125910.PMID16741119.S2CID42150441.

- ^Lancaster, Andrew (2009)."Y Haplogroups, Archaeological Cultures and Language Families: a Review of the Multidisciplinary Comparisons using the case of E-M35"(PDF).Journal of Genetic Genealogy.5(1). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2016-05-06.Retrieved2010-02-23.

- ^Findings include remains of food items carried to theLevantfromNorth Africa——ParthenocarpicfigsandNileshellfish(please refer toNatufian culture#Long-distance exchange).

- ^Chicki, L; Nichols, RA; Barbujani, G; Beaumont, MA (2002)."Y genetic data support the Neolithic demic diffusion model".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA.99(17): 11008–11013.Bibcode:2002PNAS...9911008C.doi:10.1073/pnas.162158799.PMC123201.PMID12167671.

- ^Dupanloup, I. (July 2004)."Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans".Molecular Biology and Evolution.21(7): 1361–1372.doi:10.1093/molbev/msh135.PMID15044595.

- ^Semino, O.; Magri, C.; Benuzzi, G.; et al. (May 2004)."Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area".Am. J. Hum. Genet.74(5): 1023–34.doi:10.1086/386295.PMC1181965.PMID15069642.

- ^Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Minch, E. (July 1997)."Paleolithic and Neolithic lineages in the European mitochondrial gene pool".American Journal of Human Genetics.61(1): 247–254.doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64303-1.PMC1715849.PMID9246011.

- ^Chikhi, Lounès; Destro-Bisol, Giovanni; Bertorelle, Giorgio; Pascali, Vincenzo; Barbujani, Guido (1998-07-21)."Clines of nuclear DNA markers suggest a largely Neolithic ancestry of the European gene pool".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.95(15): 9053–9058.Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9053C.doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9053.PMC21201.PMID9671803.

- ^M. Zvelebil, inHunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies and the Transition to Farming,M. Zvelebil (editor), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK (1986) pp. 5–15, 167–188.

- ^P. Bellwood,First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies,Blackwell: Malden, MA (2005).

- ^Dokládal, M.; Brožek, J. (1961). "Physical Anthropology in Czechoslovakia: Recent Developments".Curr. Anthropol.2(5): 455–477.doi:10.1086/200228.S2CID161324951.

- ^Bar-Yosef, O. (1998). "The Natufian culture in the Levant, threshold to the origins of agriculture".Evol. Anthropol.6(5): 159–177.doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::aid-evan4>3.0.co;2-7.S2CID35814375.

- ^Zvelebil, M. (1989). "On the transition to farming in Europe, or what was spreading with the Neolithic: a reply to Ammerman (1989)".Antiquity.63(239): 379–383.doi:10.1017/s0003598x00076110.S2CID162882505.

- ^Steadman & McMahon 2011,p. 233.

- ^Steadman & McMahon 2011,p. 522.

- ^Steadman & McMahon 2011,p. 556.

- ^Potts 2012,p. 28.

- ^Potts 2012,p. 570.

- ^Potts 2012,p. 584.

- ^Rubio, Gonzalo (January 1999). "On the Alleged" Pre-Sumerian Substratum "".Journal of Cuneiform Studies.51:1–16.doi:10.2307/1359726.JSTOR1359726.S2CID163985956.

- ^Heggarty, Paul; et al. (2023-07-28)."Language trees with sampled ancestors support a hybrid model for the origin of Indo-European languages".Science.381(6656): eabg0818.doi:10.1126/science.abg0818.hdl:10234/204329.PMID37499002.

Bibliography

- Jared Diamond,Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years,1997.

- Anderson, Clifford Norman.The Fertile Crescent: Travels In the Footsteps of Ancient Science.2d ed., rev. Fort Lauderdale: Sylvester Press, 1972.

- Deckers, Katleen.Holocene Landscapes Through Time In the Fertile Crescent.Turnhout: Brepols, 2011.

- Ephʻal, Israel.The Ancient Arabs: Nomads On the Borders of the Fertile Crescent 9th–5th Centuries B.C.Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1982.

- Kajzer, Małgorzata, Łukasz Miszk, and Maciej Wacławik.The Land of Fertility I: South-East Mediterranean Since the Bronze Age to the Muslim Conquest.Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

- Kozłowski, Stefan Karol.The Eastern Wing of the Fertile Crescent: Late Prehistory of Greater Mesopotamian Lithic Industries.Oxford: Archaeopress, 1999.

- Potts, Daniel T. (21 May 2012). Potts, D. T (ed.).A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East.Vol. 1.John Wiley & Sons.p. 1445.doi:10.1002/9781444360790.ISBN9781405189880.

- Steadman, Sharon R.; McMahon, Gregory (15 September 2011).The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE).OUP.p. 1174.ISBN9780195376142.

- Thomas, Alexander R.The Evolution of the Ancient City: Urban Theory and the Archaeology of the Fertile Crescent.Lanham: Lexington Books/Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010.

External links

- Ancient Fertile Crescent Almost Gone, Satellite Images Show– fromNational GeographicNews, May 18, 2001.ArchivedOctober 16, 2008, at theWayback Machine

- http://www.claudiusptolemy.org/AbshireGusevStafeyev_ProceedingsVenice2017.pdfCorey Abshire, Dmitri Gusev, Sergey Stafeyev The Fertile Crescent in Ptolemy’s “Geography”: a new digital reconstruction for modern GIS tools

- 1910s neologisms

- Ancient Near East

- Eastern Mediterranean

- History of the Mediterranean

- Physiographic divisions

- Historical regions

- Cradle of civilization

- Agriculture in Iraq

- Agriculture in Lebanon

- Agriculture in Syria

- Agriculture in the State of Palestine

- Agriculture in Israel

- Agriculture in Jordan

- Agriculture in Iran

- Agriculture in Turkey

- Agriculture in Cyprus

- Agriculture in Egypt

- Geography of Khuzestan province