Osprey

| Osprey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Standing on its nest | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Pandionidae |

| Genus: | Pandion |

| Species: | P. haliaetus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pandion haliaetus | |

| |

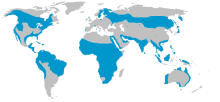

| Global range ofPandion haliaetus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Falco haliaetusLinnaeus, 1758 | |

Theosprey(/ˈɒspri,-preɪ/;[2]Pandion haliaetus), historically known assea hawk,river hawk,andfish hawk,is adiurnal,fish-eatingbird of preywith acosmopolitan range.It is a largeraptor,reaching more than 60 cm (24 in) in length and 180 cm (71 in) across the wings. It is brown on the upperparts and predominantly greyish on the head and underparts.

The osprey tolerates a wide variety ofhabitats,nesting in any location near a body of water providing an adequate food supply. It is found on all continents except Antarctica, although in South America it occurs only as a non-breedingmigrant.

As its other common names suggest, the osprey's diet consists almost exclusively of fish. It possesses specialised physical characteristics and unique behaviour in hunting itsprey.Because of its unique characteristics it is classified in its owntaxonomicgenus,Pandion,andfamily,Pandionidae.

Taxonomy

[edit]

The osprey was described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalistCarl Linnaeusunder the nameFalco haliaetusin his landmarktenth editionof hisSystema Naturae.[3][4]Linnaeus specified thetype localityas Europe, but in 1761 he restricted the locality to Sweden.[4][5]The osprey is the only species placed in thegenusPandionthat was introduced by the French zoologistMarie Jules César Savignyin 1809.[6][7]The genus is the sole member of the family Pandionidae.[7]The species has always presented a riddle to taxonomists, but here it is treated as the soleliving memberof the family Pandionidae, and the family listed in its traditional place as part of the orderAccipitriformes.Other schemes place it alongside the hawks and eagles in the familyAccipitridae.[4]TheSibley-Ahlquist taxonomyhas placed it together with the other diurnal raptors in a greatly enlargedCiconiiformes,but this results in an unnaturalparaphyleticclassification.[8]Molecular phylogeneticanalysis has found that the family Pandionidae issisterto the family Accipitridae. It is estimated that the two families diverged around 50.8 million years ago.[9]

The osprey is unusual in that it is a sole living species that occurs nearly worldwide. Even the fewsubspeciesare not unequivocally separable. There are four generally recognised subspecies, although differences are small, andITISlists only the first three.[10]

- Pandion haliaetus haliaetus(Linnaeus, 1758)– the Eurasian osprey is the nominate subspecies that occurs across thePalearctic realmand several parts ofsub-Saharan Africafrom theAzoresand theIberian Peninsulaeast to Japan andKamchatka Peninsula,throughoutSouthandSoutheast Asia,the Indian subcontinent,Madagascarand much of the African coastline.[11]

- P. haliaetus carolinensis(Gmelin,1788)– the American or North American osprey occurs from Alaska and Canada to much ofCentralandSouth America,except Chile and Patagonia. It is larger, darker bodied and has a paler breast than the European osprey.[11]

- P. haliaetus ridgwayiMaynard,1887– Ridgway's osprey occurs in theCaribbeanislands. It has a very pale head and breast and a weak eye mask.[11]It is non-migratory. Its scientific name commemoratesRobert Ridgway.[12]

- P. haliaetus cristatus(Vieillot,1816)– the Australasian osprey is the smallest and most distinctive subspecies that occurs along the entire marine coastline of Australia and some larger freshwater rivers as well as inTasmania.It is not migratory.[11]Some authorities have assigned it full species-status[13]asPandion cristatus,also known as theeastern osprey.[14]A 2018 genetic study usingmicrosatellitedata showed only lowgenetic divergencebetweencristatusand the other subspecies.[15]

Fossil record

[edit]Twoextinctspecies were named from the fossil record.[16]Pandion homalopterondescribed by Stuart L. Warter in 1976 was found in marineMiddle Miocenedeposits of theBarstovianage in the southern part ofCalifornia.The second speciesPandion lovensiswas described byJonathan J. Beckerin 1985 and found inFlorida;it dates to the LateClarendonianand possibly represents a separate lineage from that ofP. homalopteronandP. haliaetus.A number of claw fossils have been recovered from Pliocene and Pleistocene sediments in Florida andSouth Carolina.[citation needed]

The oldest recognized family Pandionidae fossils were recovered from the Oligocene ageJebel Qatrani FormationinFaiyum Governorate,Egypt.However, they are not complete enough to assign to a specific genus.[17]Another Pandionidae claw fossil was recovered fromEarly Oligocenedeposits in theMainzbasin, Germany, and was described in 2006 byGerald Mayr.[18]

Etymology

[edit]The genus namePandionderives fromPandíōnΠανδίων,themythicalGreekking of Athensand grandfather ofTheseus,Pandion II.The species namehaliaetus(Latin:haliaeetus)[19]comes fromGreekἁλιάετοςhaliáetos"sea-eagle" (alsoἁλιαίετοςhaliaietos) from the combining formἁλι-hali-ofἅλςhals"sea" andἀετόςaetos,"eagle".[20][21]

The origins ofospreyare obscure;[22]the word itself was first recorded around 1460, derived via theAnglo-Frenchosprietand theMedieval Latinavis prede"bird of prey," from theLatinavis praedaethough theOxford English Dictionarynotes a connection with theLatinossifragaor "bone breaker" ofPliny the Elder.[23][24]However, this term referred to thebearded vulture.[25]

Description

[edit]The osprey differs in several respects from otherdiurnalbirds of prey. Its toes are of equal length, itstarsiarereticulate,and its talons are rounded, rather than grooved. The osprey and owls are the only raptors whose outer toe is reversible, allowing them to grasp their prey with two toes in front and two behind. This is particularly helpful when they grab slippery fish.[26] The osprey is 0.9–2.1 kg (2.0–4.6 lb) in weight and 50–66 cm (20–26 in) in length with a 127–180 cm (50–71 in) wingspan. It is, thus, of similar size to the largest members of theButeoorFalcogenera. The subspecies are fairly close in size, with the nominate subspecies averaging 1.53 kg (3.4 lb),P. h. carolinensisaveraging 1.7 kg (3.7 lb) andP. h. cristatusaveraging 1.25 kg (2.8 lb). Thewing chordmeasures 38 to 52 cm (15 to 20 in), the tail measures 16.5 to 24 cm (6.5 to 9.4 in) and the tarsus is 5.2–6.6 cm (2.0–2.6 in).[27][28]

The upperparts are a deep, glossy brown, while the breast is white, sometimes streaked with brown, and the underparts are pure white. The head is white with a dark mask across the eyes, reaching to the sides of the neck.[29]The irises of the eyes are golden to brown, and the transparent nictitating membrane is pale blue. The bill is black, with a bluecere,and the feet are white with black talons.[26]On the underside of the wings the wrists are black, which serves as afield mark.[30]A short tail and long, narrow wings with four long, finger-like feathers, and a shorter fifth, give it a very distinctive appearance.[31]

The sexes appear fairly similar, but the adult male can be distinguished from the female by its slimmer body and narrower wings. The breast band of the male is also weaker than that of the female or is non-existent, and the underwing coverts of the male are more uniformly pale. It is straightforward to determine the sex in a breeding pair, but harder with individual birds.[31]

The juvenile osprey may be identified by buff fringes to the plumage of the upperparts, a buff tone to the underparts, and streaked feathers on the head. During spring, barring on the underwings and flight feathers is a better indicator of a young bird, due to wear on the upperparts.[29]

In flight, the osprey has arched wings and drooping "hands", giving it agull-likeappearance. The call is a series of sharp whistles, described ascheep, cheep,oryewk, yewk.If disturbed by activity near the nest, the call is a frenziedcheereek![32]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

The osprey is the second most widely distributed raptor species, after theperegrine falcon,and is one of only six land-birds with a worldwide distribution.[33]It is found in temperate and tropical regions of all continents, exceptAntarctica.In North America it breeds fromAlaskaandNewfoundlandsouth to theGulf CoastandFlorida,wintering further south from the southern United States through to Argentina.[34]It is found in summer throughout Europe north into Ireland, Scandinavia, Finland and Great Britain though not Iceland, and winters inNorth Africa.[35]In Australia it is mainlysedentaryand found patchily around the coastline, though it is a non-breeding visitor to easternVictoriaandTasmania.[36]

There is a 1,000 km (620 mi) gap, corresponding with the coast of theNullarbor Plain,between its westernmost breeding site inSouth Australiaand the nearest breeding sites to the west inWestern Australia.[37]In the islands of thePacificit is found in theBismarck Islands,Solomon IslandsandNew Caledonia,andfossilremains of adults and juveniles have been found inTonga,where it probably was wiped out by arriving humans.[38]It is possible it may once have ranged acrossVanuatuandFijias well. It is an uncommon to fairly common winter visitor to all parts of South Asia,[39]andSoutheast AsiafromMyanmarthrough toIndochinaand southern China,Indonesia,Malaysia, and the Philippines.[40]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Diet

[edit]

The osprey ispiscivorous,with fish making up 99% of its diet.[41]It typically takes live fish weighing 150–300 g (5.3–10.6 oz) and about 25–35 cm (9.8–13.8 in) in length, but virtually any type of fish from 50 g (1.8 oz) to 2 kg (4.4 lb) can be taken.[27]Even larger 2.8 kg (6.2 lb)northern pike(Esox lucius) has been taken inRussia.[42]The species rarely scavenges dead or dying fish.[43]

Ospreys have a vision that is well adapted to detecting underwater objects from the air. Prey is first sighted when the osprey is 10–40 m (33–131 ft) above the water, after which the bird hovers momentarily and then plunges feet first into the water.[44]They catch fish by diving into a body of water, oftentimes completely submerging their entire bodies. As an osprey dives it adjusts the angle of its flight to account for the distortion of the fish's image caused byrefraction.Ospreys will typically eat on a nearby perch but have also been known to carry fish for longer distances.[45]

Occasionally, the osprey may prey onrodents,rabbits,hares,othermammals,snakes,turtles,frogs,birds,salamanders,conchs,andcrustaceans.[43][46][47]Reports of ospreys feeding on carrion are rare. They have been observed eating deadwhite-tailed deerandVirginia opossums.[48]

Adaptations

[edit]The osprey has severaladaptationsthat suit its piscivorous lifestyle. These include reversible outer toes,[49]sharpspiculeson the underside of the toes,[49]closable nostrils to keep out water during dives, backward-facing scales on the talons which act as barbs to help hold its catch and dense plumage which is oily and prevents its feathers from getting waterlogged.[50]

Reproduction

[edit]

The osprey breeds near freshwater lakes and rivers, and sometimes on coastal brackish waters. Rocky outcrops just offshore are used inRottnest Islandoff the coast ofWestern Australia,where there are 14 or so similar nesting sites of which five to seven are used in any one year. Many are renovated each season, and some have been used for 70 years. The nest is a large heap of sticks, driftwood, turf, or seaweed built in forks of trees, rocky outcrops, utility poles, artificial platforms, or offshore islets.[41][51]As wide as 2 meters and weighing about 135 kg (298 lb), large nests on utility poles may befire hazardsand have causedpower outages.[52]

Generally, ospreys reach sexual maturity and begin breeding around the age of three to four, though in some regions with high osprey densities, such asChesapeake Bayin the United States, they may not start breeding until five to seven years old, and there may be a shortage of suitable tall structures. If there are no nesting sites available, young ospreys may be forced to delay breeding. To ease this problem, posts are sometimes erected to provide more sites suitable for nest building.[53] The nesting platform design developed by the organizationCitizens United to Protect the Maurice River and Its Tributaries, Inc.has become the official design of theState of New Jersey,U.S. The nesting platform plans and materials list, available online, have been utilized by people from a number of different geographical regions.[54]There is a global site for mapping osprey nest locations and logging observations on reproductive success.[55]

Ospreys usually mate for life. Rarely,polyandryhas been recorded.[56]The breeding season varies according to latitude: spring (September–October) in southern Australia, April to July in northern Australia, and winter (June–August) in southern Queensland.[51]In spring, the pair begins a five-month period of partnership to raise their young. The female lays two to foureggswithin a month and relies on the size of the nest to conserve heat. The eggs are whitish with bold splotches of reddish-brown and are about 6.2 cm × 4.5 cm (2.4 in × 1.8 in) and weigh about 65 g (2.3 oz).[51]The eggs are incubated for about 35–43 days to hatching.[57]

The newly hatched chicks weigh only 50–60 g (1.8–2.1 oz), but fledge in 8–10 weeks. A study onKangaroo Island,South Australia, had an average time between hatching and fledging of 69 days. The same study found an average of 0.66 young fledged per year per occupied territory, and 0.92 young fledged per year per active nest. Some 22% of surviving young either remained on the island or returned at maturity to join the breeding population.[56]When food is scarce, the first chicks to hatch are most likely to survive. The typical lifespan is 7–10 years, though rarely individuals can grow to as old as 20–25 years.[citation needed]The oldest European wild osprey on record lived to be over thirty years of age.[citation needed]

Migration

[edit]European breeders winter in Africa.[58]American and Canadian breeders winter in South America, although some stay in the southernmost U.S. states such asFloridaandCalifornia.[59]Some ospreys from Florida migrate to South America.[60]Australasianospreys tend not tomigrate.

Studies of Swedish ospreys showed that females tend to migrate to Africa earlier than males. More stopovers are made during their autumn migration. The variation of timing and duration in autumn was more variable than in spring. Although migrating predominantly during the day, they sometimes fly in the dark hours, particularly in crossings over water and cover on average 260–280 km (160–170 mi) per day with a maximum of 431 km (268 mi) per day.[61]European birds may also winter in South Asia, as indicated by an osprey tagged in Norway being monitored in western India.[62]In the Mediterranean, ospreys show partial migratory behaviour with some individuals remaining resident, whilst others undertake relatively short migration trips.[63]

Mortality

[edit]Swedish ospreys have a significantly higher mortality rate during migration seasons than during stationary periods, with more than half of the total annual mortality occurring during migration.[64]These deaths can also be categorized into spatial patterns: Spring mortality occurs mainly in Africa, which can be traced to crossing theSahara desert.Mortality can also occur through mishaps with human utilities, such as nesting near overhead electric cables or collisions with aircraft.[65]

Conservation

[edit]

The osprey has a large range, covering 9,670,000 km2(3,730,000 sq mi) in just Africa and the Americas, and has a large global population estimated at 460,000 individuals. Although global population trends have not been quantified, the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), and for these reasons, the species is evaluated asLeast Concern.[1]There is evidence for regional decline in South Australia where former territories at locations in theSpencer Gulfand along the lowerMurray Riverhave been vacant for decades.[37]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the main threats to osprey populations were egg collectors and hunting of the adults along with other birds of prey,[66][67]but osprey populations declined drastically in many areas in the 1950s and 1960s; this appeared to be in part due to the toxic effects of insecticides such asDDTon reproduction.[68]The pesticide interfered with the bird'scalciummetabolism which resulted in thin-shelled, easily broken or infertile eggs.[34]Possibly because of the banning of DDT in many countries in the early 1970s, together with reduced persecution, the osprey, as well as other affectedbird of preyspecies, have made significant recoveries.[41]In South Australia, nesting sites on theEyre PeninsulaandKangaroo Islandare vulnerable to unmanaged coastal recreation and encroaching urban development.[37]

Cultural depictions

[edit]Literature

[edit]- The Roman writerPliny the Elderreported that parent ospreys made their young fly up to the sun as a test, and dispatched any that failed.[69]

- Another odd legend regarding this fish-eating bird of prey, derived from the writings ofAlbertus Magnusand recorded inHolinshed'sChronicles,was that it had one webbed foot and one taloned foot.[67][70]

- The osprey is mentioned in the famous Chinese folk poem "guan guan ju jiu"( quan quan sư cưu );" ju jiu "Sư cưu refers to the osprey, and" guan guan "( quan quan ) to its voice. In the poem, the osprey is considered to be an icon of fidelity and harmony between wife and husband, due to its highly monogamous habits. Some commentators have claimed that" ju jiu "in the poem is not the osprey but themallard duck,since the osprey cannot make the sound "guan guan".[71][72]

- The Irish poetWilliam Butler Yeatsused a grey wandering osprey as a representation of sorrow inThe Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems(1889).[69]

- There was a medieval belief that fish were so mesmerised by the osprey that they turned belly-up in surrender,[67]and this is referenced byShakespearein Act 4 Scene 5 ofCoriolanus:

I think he'll be to Rome

As is the osprey to the fish, who takes it

By sovereignty of nature.

Iconography

[edit]

- Inheraldry,the osprey is typically depicted as a white eagle,[70]often maintaining a fish in its talons or beak, and termed a "sea-eagle". It is historically regarded as a symbol of vision and abundance; more recently it has become a symbol of positive responses to nature,[67]and has been featured on more than 50 internationalpostage stamps.[73]

- In 1994, the osprey was declared the provincial bird ofNova Scotia,Canada.[74]

Sports

[edit]TheSeattle Seahawksare a professionalAmerican footballteam in theNational Football League(NFL).[75]

Other

[edit]So-called "osprey" plumes were an important item in theplume tradeof the late 19th century and used in hats including those used as part of the army uniform. Despite their name, these plumes were actually obtained fromegrets.[76]

During the 2017 regular session of theOregon Legislature,there was a short-lived controversy over thewestern meadowlark's status as the state bird versus the osprey. The sometimes-spirited debate included state representativeRich Vialplaying the meadowlark's song on his smartphone over the House microphone.[77]A compromise was reached in SCR 18,[78]which was passed on the last day of the session, designating the western meadowlark as the statesongbirdand the osprey as the stateraptor.

References

[edit]- ^abBirdLife International (2021)."Pandion haliaetus".IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.2021:e.T22694938A206628879.doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22694938A206628879.en.Retrieved9 March2022.

- ^"osprey".The Chambers Dictionary(9th ed.). Chambers. 2003.ISBN0-550-10105-5.

- ^Linnaeus, Carl(1758).Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis(in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 91.

- ^abcMayr, Ernst;Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979).Check-List of Birds of the World.Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 279.

- ^Linnaeus, Carl(1761).Fauna svecica, sistens animalia sveciae regni mammalia, aves amphibia, pisces, insecta, vermes(in Latin) (2nd ed.). Stockholmiae: Sumtu & Literis Direct. Laurentii Salvii. p. 22.

- ^Savigny, Marie Jules César(1809).Description de l'Égypte: Histoire naturelle(in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Imprimerie impériale. pp.69,95.

- ^abGill, Frank;Donsker, David;Rasmussen, Pamela,eds. (December 2023)."Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors".IOC World Bird List Version 14.1.International Ornithologists' Union.Retrieved13 June2024.

- ^Salzman, Eric (1993)."Sibley's Classification of Birds".Birding.58(2): 91–98. Archived fromthe originalon 13 April 2018.Retrieved5 September2007.

- ^Catanach, T.A.; Halley, M.R.; Pirro, S. (2024). "Enigmas no longer: using ultraconserved elements to place several unusual hawk taxa and address the non-monophyly of the genusAccipiter(Accipitriformes: Accipitridae) ".Biological Journal of the Linnean Society:blae028.doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blae028.

- ^"Pandion haliaetus".Integrated Taxonomic Information System.Retrieved26 October2022.

- ^abcdTesky, Julie L. (1993)."Pandion haliaetus".U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.Retrieved6 September2007.

- ^Barrow, M.V. (1998).A passion for Birds: American ornithology after Audubon.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-04402-3.

- ^Christidis, L.; Boles, W.E. (2008).Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds.Csiro Publishing.ISBN978-0643065116.

- ^"Pandion cristatus".Avibase.

- ^Monti, F.; Delfour, F.; Arnal, V.; Zenboudji, S.; Duriez, O.; Montgelard, C. (2018). "Genetic connectivity among osprey populations and consequences for conservation: philopatry versus dispersal as key factors".Conservation Genetics.19(4): 839–851.doi:10.1007/s10592-018-1058-7.

- ^"Pandionentry ".Retrieved2 December2010.

- ^Olson, S.L. (1985). "Chapter 2. The fossil record of birds".Avian Biology.Vol. 8. Academic Press. pp. 79–238.doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-249408-6.50011-X.

- ^Mayr, Gerald(2006). "An osprey (Aves: Accipitridae: Pandioninae) from the early Oligocene of Germany".Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments.86(1): 93–96.doi:10.1007/BF03043637.S2CID140677653.

- ^haliaeetos.Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short.A Latin DictionaryonPerseus Project.

- ^Jobling, James A (2010).The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names.London: Christopher Helm. pp.185,290–291.ISBN978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ἁλιάετος,ἅλς,ἀετός.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;A Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project.

- ^Livingston, C.H. (1943). "Osprey and Ostril".Modern Language Notes.58(2): 91–98.doi:10.2307/2911426.JSTOR2911426.

- ^Morris, W. (1969).The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language.Boston: American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc. and Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^"Osprey".Online Etymology Dictionary.Retrieved29 June2007.

- ^Simpson, J.; Weiner, E., eds. (1989). "Osprey".Oxford English Dictionary(2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.ISBN0-19-861186-2.

- ^abTerres, J.K.(1980).The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds.New York, NY: Knopf. pp.644–646.ISBN0-394-46651-9.

- ^abFerguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D.A. (2001).Raptors of the World.Houghton Mifflin Company.ISBN978-0-618-12762-7.

- ^"Osprey".All About Birds.Cornell Lab of Ornithology.–P. h. carolinensis

- ^ab"Osprey"(PDF).Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection. 1999. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 10 June 2012.Retrieved30 September2007.

- ^Robbins, C. S.; Bruun, Bertel; Zim, H. S.; Singer, A. (1983).Birds of North America(Revised ed.). New York: Golden Press. pp. 78–79.ISBN0-307-37002-X.

- ^abForsman, Dick (2008).The Raptors of Europe & the Middle East: A Handbook of Field Identification.Princeton University Press. pp. 21–25.ISBN978-0-85661-098-1.

- ^Peterson, Roger Tory(1999).A Field Guide to the Birds.Houghton Mifflin Company. p.136.ISBN978-0-395-91176-1.

- ^Monti, Flavio; Duriez, Olivier; Arnal, Véronique; Dominici, Jean-Marie; Sforzi, Andrea; Fusani, Leonida; Grémillet, David; Montgelard, Claudine (2015)."Being cosmopolitan: evolutionary history and phylogeography of a specialized raptor, the OspreyPandion haliaetus".BMC Evolutionary Biology.15(1): 255.Bibcode:2015BMCEE..15..255M.doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0535-6.PMC4650845.PMID26577665.

- ^abBull, J.; Farrand, J. Jr (1987).Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds: Eastern Region.New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p.469.ISBN0-394-41405-5.

- ^Hume, R. (2002).RSPB Birds of Britain and Europe.London: Dorling Kindersley. p.89.ISBN0-7513-1234-7.

- ^Simpson, K.; Day, N.; Trusler, P. (1993).Field Guide to the Birds of Australia.Ringwood, Victoria: Viking O'Neil. p. 66.ISBN0-670-90478-3.

- ^abcDennis, T.E. (2007). "Distribution and status of the Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) in South Australia ".Emu.107(4): 294–299.Bibcode:2007EmuAO.107..294D.doi:10.1071/MU07009.S2CID84883853.

- ^Steadman, D. (2006).Extinction and Biogeography in Tropical Pacific Birds.University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-77142-7.

- ^Rasmussen, P.C.;Anderton, J.C. (2005).Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide Vols 1 & 2.Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions.ISBN978-8496553859.

- ^Strange, M. (2000).A Photographic Guide to the Birds of Southeast Asia including the Philippines and Borneo.Singapore: Periplus. p. 70.ISBN962-593-403-0.

- ^abcEvans, D.L. (1982).Status Reports on Twelve Raptors: Special Scientific Report Wildlife(Report). U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ^Adrianova, Olga V. & Boris N. Kashevarov. "Some results of long-term raptor monitoring in the Kostomuksha Nature Reserve." Status of Raptor Populations in Eastern Fennoscandia. Kostomuksha (2005).

- ^abFerguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D.A.; Franklin, K.; Mead, D.; Burton, P. (2001).Raptors of the world.Helm Identification Guides.ISBN9780618127627.

- ^Poole, A.F.; Bierregaard, R.O.; Martell, M.S. (2002). Poole, A.; Gill, F. (eds.)."Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) ".The Birds of North America.683(683). Philadelphia, PA: The Birds of North America, Inc.doi:10.2173/tbna.683.p.

- ^Dunne, P. (2012).Hawks in flight: the flight identification of North American raptors(Second ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.ISBN978-0-395-70959-7.

- ^"Osprey".The Peregrine Fund.

- ^Goenka, D.N. (1985)."The Osprey (Pandion haliaetus haliaetus) preying on a Gull ".Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society.82(1): 193–194.

- ^"Pandion haliaetus(Osprey) ".Animal Diversity Web.

- ^abClark, W.S.; Wheeler, B.K. (1987).A field guide to Hawks of North America.Boston: Houghton Mifflin.ISBN0-395-36001-3.

- ^"Pandion haliaetus Linnaeus Osprey "(PDF).Michigan Natural Features Inventory.Retrieved11 May2016.

- ^abcBeruldsen, G. (2003).Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs.Kenmore Hills, Queensland: G. Beruldsen. p. 196.ISBN0-646-42798-9.

- ^"Osprey nest moved by BC Hydro crews weighs 300 pounds".CBC News - British Columbia, Canada. 28 November 2014.Retrieved18 May2016.

- ^"Osprey".Chesapeake Bay Program.Retrieved4 April2013.

- ^"Osprey platform plans".Retrieved23 November2011.

- ^"Project Osprey Watch".Osprey-watch.org.Retrieved30 September2013.

- ^abDennis, T.E. (2007). "Reproductive activity in the Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) on Kangaroo Island, South Australia ".Emu.107(4): 300–307.Bibcode:2007EmuAO.107..300D.doi:10.1071/MU07010.S2CID85099678.

- ^Poole, Alan F.Ospreys, A Natural and Unnatural History1989

- ^Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (2001).Birds of Europe.Princeton University Press. pp. 74–75.ISBN0-691-05054-6.

- ^"Migration Strategies and Wintering Areas of North American ospreys as Revealed by Satellite Telemetry"(PDF).Newsletter Winter 2000.Microwave Telemetry Inc. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 12 May 2012.Retrieved2 December2008.

- ^Martell, M.S.; Mcmillian, M.A.; Solensky, M.J.; Mealey, B.K. (2004)."Partial migration and wintering use of Florida by ospreys"(PDF).Journal of Raptor Research.38(1): 55–61.mirrorArchived26 April 2012 at theWayback Machine

- ^Alerstam, T.; Hake, M.; Kjellén, N. (2006). "Temporal and spatial patterns of repeated migratory journeys by ospreys".Animal Behaviour.71(3): 555–566.doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.05.016.S2CID53149787.

- ^Mundkur, Taej (1988)."Recovery of a Norwegian ringed Osprey in Gujarat, India".Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society.85(1): 190.

- ^Monti, F.; Grémillet, D.; Sforzi, A.; Sammuri, G.; Dominici, J.M.; Bagur, R.T.; Navarro, A.M.; Fusani, L.; Duriez, O. (2018)."Migration and wintering strategies in vulnerable Mediterranean Osprey populations".Ibis.160(3): 554–567.doi:10.1111/ibi.12567.

- ^Klaassen, R. H. G.; Hake, M.; Strandberg, R.; Koks, B.J.; Trierweiler, C.; Exo, K.-M.; Bairlein, F.; Alerstam, T. (2013)."When and where does mortality occur in migratory birds? Direct evidence from long-term satellite tracking of raptors".Journal of Animal Ecology.83(1): 176–184.doi:10.1111/1365-2656.12135.PMID24102110.

- ^Washburn, B.E. (2014)."Human–Osprey Conflicts: Industry, Utilities, Communication, and Transportation".Journal of Raptor Research.48(4): 387–395.doi:10.3356/jrr-ospr-13-04.1.S2CID30695523.

- ^Kirschbaum, K.; Watkins, P."Pandion haliaetus".University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.Retrieved3 January2008.

- ^abcdCocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005).Birds Britannica.London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 136–141.ISBN0-7011-6907-9.

- ^Ames, P. (1966). "DDT Residues in the eggs of the Osprey in the North-eastern United States and their relation to nesting success".Journal of Applied Ecology.3(Suppl). British Ecological Society: 87–97.Bibcode:1966JApEc...3...87A.doi:10.2307/2401447.JSTOR2401447.

- ^abde Vries, Ad (1976).Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery.Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. p.352.ISBN0-7204-8021-3.

- ^abCooper, J.C. (1992).Symbolic and Mythological Animals.London: Aquarian Press. p. 170.ISBN1-85538-118-4.

- ^H. U. Vogel; G. N. Dux, eds. (2010).Concepts of nature: a Chinese-European cross-cultural perspective.Vol. 1. Brill.ISBN978-9004185265.

- ^Jiang, Yi; Lepore, Ernest (2015).Language and Value: ProtoSociology.Vol. 31. BoD–Books on Demand.ISBN9783738622478.

- ^"Osprey".Birds of the World on Postage Stamps.Archived from the original on 16 September 2000.Retrieved1 January2008.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^"The Osprey".Province of Nova Scotia. Archived fromthe originalon 23 May 2013.Retrieved3 June2013.

- ^"Seattle Seahawks".www.seahawks.com.Retrieved1 May2024.

- ^Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (1906)."Birds and Millinery".Bird Notes and News.Vol. 2, no. 3. pp. 29–30.Retrieved18 September2023– via Internet Archive.

- ^"Lawmakers adjourn 2017 session with mixed results for biggest priorities".OregonLive.com.8 July 2017.Retrieved15 October2017.

- ^"SCR 18".state.or.us.Retrieved15 October2017.

External links

[edit] The full text ofThe Fish Hawk, or Ospreyby John James Audubonat Wikisource

The full text ofThe Fish Hawk, or Ospreyby John James Audubonat Wikisource- Explore Species: Ospreyat eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Osprey photo galleryat VIREO (Drexel University)

- Pandion haliaetus species accountat Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- UK Osprey InformationRoyal Society for the Protection of Birds

- Ospreymedia fromARKive

- Osprey species text inThe Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Osprey –Pandion haliaetus– USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Osprey InfoAnimal Diversity Web

- USDA Forest Service osprey data

- Osprey Nest Monitoring Program at OspreyWatch

- Ospreys Rebound, Rely On Help From HumansArchived5 February 2015 at theWayback MachineDocumentary produced byOregon Field Guide

- Hellgate Ospreys Bird CamMontana Osprey Project, hosted by the Cornell Lab