Fishery

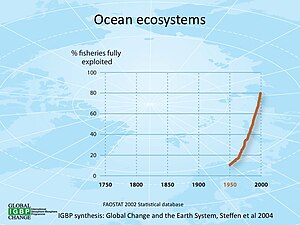

Fisherycan mean either theenterpriseofraisingorharvestingfishand otheraquatic life[1]or, more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place (a.k.a.,fishing grounds).[2]Commercial fisheries includewild fisheriesandfish farms,both infreshwaterwaterbodies (about 10% of all catch) and the oceans (about 90%). About 500 million people worldwide are economically dependent on fisheries. 171 million tonnes of fish were produced in 2016, butoverfishingis an increasing problem, causing declines in some populations.

Because of their economic and social importance, fisheries are governed by complexfisheries managementpractices andlegal regimesthat vary widely across countries. Historically, fisheries were treated with a "first-come, first-served"approach, but recent threats from human overfishing and environmental issues have required increased regulation of fisheries to prevent conflict and increase profitable economic activity on the fishery. Modern jurisdiction over fisheries is often established by a mix of international treaties and local laws.

Declining fish populations,marine pollution,and the destruction of important coastal ecosystems have introduced increasing uncertainty in important fisheries worldwide, threateningeconomic securityandfood securityin many parts of the world. These challenges are further complicated by the changes in theocean caused by climate change,which may extend the range of some fisheries while dramatically reducing the sustainability of other fisheries.

Definitions

[edit]According to theFAO,"...a fishery is an activity leading to harvesting of fish. It may involve capture of wild fish or raising of fish through aquaculture." It is typically defined in terms of the "people involved, species or type of fish, area of water or seabed, method offishing,class of boats, purpose of the activities or a combination of the foregoing features ".[3]

The definition often includes a combination of mammal and fishfishersin a region, the latter fishing for similar species with similar gear types.[4][5]Some government and private organizations, especially those focusing onrecreational fishinginclude in their definitions not only the fishers, but the fish and habitats upon which the fish depend.[6]

The termfish

[edit]- Inbiology– the termfishis most strictly used to describe any aquaticvertebratethat hasgillsthroughout life, and can also refer to those that havelimbs(if any) orappendagesin the shape offish fins.[7]Many types of aquatic animals commonly referred to as "fish" are not fishin this strict sense;examples includeshellfish,cuttlefish,starfish,crayfishandjellyfish.In the strict sense, all vertebrates arecladisticallyfish, although colloquially "fish" is aparaphyleticterm that only refers to non-tetrapodvertebrates. In earlier times, evenbiologistsdid not make any distinction — for instance,16th centurynatural historiansoften classifiedseals,whales,amphibians,crocodilesand evenhippopotamuses,as well as a host ofmarine invertebrates,as fish.[8]

- In fisheries– the termfishis used as a collective term, and includesmollusks,crustaceansand anyaquatic animalsthat are harvested foreconomic value.[3]

- True fish– The biological definition of a fish (mentioned above) is sometimes called a "true fish", the vast majority of which areteleosts.True fish are also referred to asfinfishorfin fishto distinguish them from other invertebrateaquatic lifeharvested in fisheries or aquaculture.[9]

Types

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(January 2021) |

Thefishing industrywhich harvests fish from fisheries can be divided into three main sectors:commercial,recreationalorsubsistence.They can besaltwateror freshwater,wildorfarmed.Examples are thesalmonfishery ofAlaska,thecodfishery off theLofotenislands, thetunafishery of theEastern Pacific,or theshrimp farmfisheries in China. Capture fisheries can be broadly classified as industrial scale, small-scale or artisanal, and recreational.

Close to 90% of the world's fishery catches come from oceans and seas, as opposed to inland waters. These marine catches have remained relatively stable since the mid-nineties (between 80 and 86 million tonnes).[10]Most marine fisheries are based near thecoast.This is not only because harvesting from relatively shallow waters is easier than in the open ocean, but also because fish are much more abundant near thecoastal shelf,due to the abundance of nutrients available there fromcoastal upwellingandland runoff.However, productive wild fisheries also exist in open oceans, particularly byseamounts,and inland in lakes and rivers.

Most fisheries are wild fisheries, butfarmed fisheriesare increasing. Farming can occur in coastal areas, such as withoyster farms,[11]or theaquaculture of salmon,but more typically fish farming occurs inland, in lakes, ponds, tanks and other enclosures.

There are commercial fisheries worldwide for finfish,mollusks,crustaceansandechinoderms,and by extension,aquatic plantssuch askelp.However, a very small number of species support the majority of the world's fisheries. Some of these species areherring,cod,anchovy,tuna,flounder,mullet,squid,shrimp,salmon,crab,lobster,oysterandscallops.All except these last four provided a worldwide catch of well over amilliontonnesin 1999, with herring andsardinestogether providing a harvest of over 22 million metric tons in 1999. Many other species are harvested in smaller numbers.

Economic importance

[edit]Directly or indirectly, the livelihood of over 500 million people in developing countries depends on fisheries andaquaculture.Overfishing,including the taking of fish beyondsustainable levels,is reducingfish stocksand employment in many world regions.[12][13]It was estimated in 2014 that global fisheries were adding US$270 billion a year to globalGDP,but by full implementation of sustainable fishing, that figure could rise by as much as US$50 billion.[14]

In addition to commercial and subsistence fishing, recreational (sport) fishing is popular and economically important in many regions.[15]

Production

[edit]

Total fish production in 2016 reached an all-time high of 171 million tonnes, of which 88 percent was utilized for direct human consumption, thanks to relatively stable capture fisheries production, reduced wastage and continued aquaculture growth. This production resulted in a record-high per capita consumption of 20.3 kg in 2016.[16]Since 1961 the annual global growth in fish consumption has been twice as high as population growth. While annual growth of aquaculture has declined in recent years, significant double-digit growth is still recorded in some countries, particularly in Africa and Asia.[16]

FAO predicted in 2018 the following major trends for the period up to 2030:[16]

- World fish production, consumption and trade are expected to increase, but with a growth rate that will slow over time.

- Despite reduced capture fisheries production in China, world capture fisheries production is projected to increase slightly through increased production in other areas if resources are properly managed. Expanding world aquaculture production, although growing more slowly than in the past, is anticipated to fill the supply–demand gap.

- Prices will all increase in nominal terms while declining in real terms, although remaining high.

- Food fish supply will increase in all regions, while per capita fish consumption is expected to decline in Africa, which raises concerns in terms of food security.

- Trade in fish and fish products is expected to increase more slowly than in the past decade, but the share of fish production that is exported is projected to remain stable.

Management

[edit]

The goal offisheries managementis to producesustainablebiological, environmental and socioeconomic benefits from renewable aquatic resources.Wild fisheriesare classified as renewable when the organisms of interest (e.g.,fish,shellfish,amphibians,reptilesandmarine mammals) produce an annual biological surplus that with judicious management can be harvested withoutreducing future productivity.[17]Fishery management employs activities that protect fishery resources sosustainable exploitationis possible, drawing onfisheries scienceand possibly including theprecautionary principle.

Modern fisheries management is often referred to as a governmental system of appropriateenvironmental managementrules based on defined objectives and a mix of management means to implement the rules, which are put in place by a system ofmonitoring control and surveillance.An ecosystem approach to fisheries management has started to become a more relevant and practical way to manage fisheries.[18][19]According to theFood and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO), there are "no clear and generally accepted definitions of fisheries management".[20]However, the working definition used by the FAO and much cited elsewhere is:

The integrated process ofinformation gathering,analysis, planning, consultation, decision-making, allocation of resources and formulation and implementation, with necessarylaw enforcementto ensureenvironmental compliance,of regulations or rules which govern fisheries activities in order to ensure the continued productivity of the resources and the accomplishment of other fisheries objectives.[20]

Global goals

[edit]International attention to these issues has been captured inSustainable Development Goal 14"Life Below Water" which sets goals for international policy focused on preserving coastal ecosystems and supporting moresustainable economic practicesfor coastal communities, including in their fishery andaquaculturepractices.[21]

Law

[edit]

Fisheries lawis an emerging and specialized area of law. Fisheries law is the study and analysis of differentfisheries managementapproaches such as catch shares e.g.individual transferable quotas;TURFs; and others. The study of fisheries law is important in order to craftpolicyguidelines that maximizesustainabilityand legal enforcement.[22]This specific legal area is rarely taught at law schools around the world, which leaves a vacuum of advocacy and research. Fisheries law also takes into accountinternational treatiesandindustrynorms in order to analyze fisheries management regulations.[23]In addition, fisheries law includes access to justice for small-scale fisheries and coastal andaboriginalcommunities and labor issues such as child labor laws, employment law, and family law.[24]

Another important area of research covered in fisheries law is seafood safety. Each country, or region, around the world has a varying degree of seafood safety standards and regulations. These regulations can contain a large diversity of fisheries management schemes including quota or catch share systems. It is important to study seafood safety regulations around the world in order to craft policy guidelines from countries who have implemented effective schemes. Also, this body of research can identify areas of improvement for countries who have not yet been able to master efficient and effective seafood safety regulations.

Fisheries law also includes the study ofaquaculturelaws and regulations. Aquaculture, also known as aquafarming, is the farming of aquatic organisms, such as fish and aquatic plants. This body of research also encompasses animal feed regulations and requirements. It is important to regulate what feed is consumed by fish in order to prevent risks to human health and safety.Environmental issues

[edit]

Theenvironmental impact of fishingincludes issues such as the availability offish,overfishing,fisheries,andfisheries management;as well as the impact ofindustrial fishingon other elements of the environment, such asbycatch.[25]These issues are part ofmarine conservation,and are addressed infisheries scienceprograms. According to a 2019FAOreport, global production of fish, crustaceans, molluscs and other aquatic animals has continued to grow and reached 172.6 million tonnes in 2017, with an increase of 4.1 percent compared with 2016.[26]There is a growing gap between the supply of fish and demand, due in part toworld populationgrowth.[27]

Fishing and pollution from fishing are the largest contributors to the decline in ocean health and water quality. Ghost nets, or nets abandoned in the ocean, are made of plastic and nylon and do not decompose, wreaking extreme havoc on the wildlife and ecosystems they interrupt. Overfishing and destruction of marine ecosystems may have a significant impact on other aspects of the environment such asseabirdpopulations. On top of the overfishing, there is a seafood shortage resulting from the mass amounts of seafood waste, as well as themicroplasticsthat are polluting the seafood consumed by the public. The latter is largely caused by plastic-made fishing gear likedrift netsandlongliningequipment that are wearing down by use, lost or thrown away.[28][29]

The journalSciencepublished a four-year study in November 2006, which predicted that, at prevailing trends, the world would run out of wild-caughtseafoodin 2048. The scientists stated that the decline was a result ofoverfishing,pollutionand other environmental factors that were reducing the population of fisheries at the same time as their ecosystems were being annihilated. Many countries, such asTonga,theUnited States,AustraliaandBahamas,and international management bodies have taken steps to appropriately manage marine resources.[30][31]

Reefs are also being destroyed byoverfishingbecause of the huge nets that are dragged along the ocean floor whiletrawling.Many corals are being destroyed and, as a consequence, theecological nicheof many species is at stake.Climate change

[edit]Fisheries are affected by climate change in many ways: marineaquatic ecosystemsare being affected byrising ocean temperatures,[32]ocean acidification[33]andocean deoxygenation,whilefreshwater ecosystemsare being impacted by changes in water temperature, water flow, and fish habitat loss.[34]These effects vary in the context of each fishery.[35]Climate changeis modifying fish distributions[36]and the productivity of marine and freshwater species. Climate change is expected to lead to significant changes in the availability and trade offish products.[37]The geopolitical and economic consequences will be significant, especially for the countries most dependent on the sector. The biggest decreases in maximum catch potential can be expected in the tropics, mostly in the South Pacific regions.[37]: iv

Theimpacts of climate change on oceansystems has impacts on thesustainabilityoffisheriesandaquaculture,on the livelihoods of the communities that depend on fisheries, and on the ability of the oceans to capture and store carbon (biological pump). The effect ofsea level risemeans that coastalfishing communitiesare significantly impacted by climate change, while changing rainfall patterns and water use impact on inland freshwater fisheries and aquaculture.[38]Increased risks of floods, diseases, parasites andharmful algal bloomsare climate change impacts onaquaculturewhich can lead to losses of production and infrastructure.[37]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Fletcher, WJ; Chesson, J; Fisher, M; Sainsbury KJ; Hundloe, T; Smith, ADM and Whitworth, B (2002)The "How To" guide for wild capture fisheries.National ESD reporting framework for Australian fisheries: FRDC Project 2000/145. Page 119–120.

- ^"fishery".Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.Merriam-Webster.

- ^abFAO Fishery Glossary; "Fishery"(Entry: 98327).Rome: FAO. 2009. p. 24.Retrieved21 January2020.

- ^Madden, CJ and Grossman, DH (2004)A Framework for a Coastal/Marine Ecological Classification StandardArchivedOctober 29, 2008, at theWayback Machine.NatureServe, page 86. Prepared forNOAAunder Contract EA-133C-03-SE-0275

- ^Blackhart, K; et al. (2006).NOAA Fisheries Glossary: "Fishery"(PDF)(Revised ed.). Silver Spring MD: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 16.Retrieved21 January2020.

- ^"Open Access Fisheries Journals | Medical Journals".www.iomcworld.org.Retrieved2022-07-06.

- ^Nelson, Joseph S. (2006).Fishes of the World.John Wiley & Sons,Inc. p. 2.ISBN0-471-25031-7.

- ^Jr. Cleveland P Hickman, Larry S. Roberts, Allan L. Larson:Integrated Principles of Zoology,McGraw-Hill Publishing Co, 2001,ISBN0-07-290961-7

- ^"Finfish – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics".www.sciencedirect.com.Retrieved2022-07-06.

- ^"Scientific Facts on Fisheries".GreenFacts Website. 2009-03-02.Retrieved2009-03-25.

- ^New Zealand Seafood Industry Council.Mussel Farming.Archived2008-12-28 at theWayback Machine

- ^C. Michael Hogan (2010)Overfishing,Encyclopedia of earth, topic ed. Sidney Draggan, ed. in chief C. Cleveland, National Council on Science and the Environment (NCSE), Washington, DC

- ^Fisheries and Aquaculture in our Changing ClimatePolicy brief of theFAOfor theUNFCCCCOP-15in Copenhagen, December 2009.

- ^"Prince Charles calls for greater sustainability in fisheries".London Mercury. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-07-14.Retrieved13 July2014.

- ^Hubert, Wayne; Quist, Michael, eds. (2010).Inland Fisheries Management in North America(Third ed.). Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society. p. 736.ISBN978-1-934874-16-5.

- ^abcIn brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018(PDF).FAO. 2018.

- ^Lackey, Robert; Nielsen, Larry, eds. (1980).Fisheries management.Blackwell. p. 422.ISBN978-0632006151.

- ^"The ecosystem approach to fisheries"(PDF).FAO.Retrieved7 July2023.

- ^Garcia SM, Zerbi A, Aliaume C, Do Chi T, Lasserre G (2003).The ecosystem approach to fisheries. Issues, terminology, principles, institutional foundations, implementation and outlook.FAO.ISBN9789251049600.

- ^abFAO (1997)Fisheries ManagementSection 1.2, Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries. FAO, Rome.ISBN92-5-103962-3

- ^United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017,Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development(A/RES/71/313)

- ^National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Fisheries Service, aboutus.htm

- ^Kevern L. Cochrane, A Fishery Manager’s Guidebook: Management Measures and their Application, Fisheries Technical Paper 424, available atftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/004/y3427e/y3427e00.pdf

- ^Stewart, Robert (16 April 2009)."Fisheries Issues".Oceanography in the 21st Century – An Online Textbook.OceanWorld. Archived fromthe originalon Apr 28, 2016.

- ^Frouz, Jan; Frouzová, Jaroslava (2022).Applied Ecology.doi:10.1007/978-3-030-83225-4.ISBN978-3-030-83224-7.S2CID245009867.

- ^Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2019)."Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics 2017"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2019-10-26.

- ^"Global population growth, wild fish stocks, and the future of aquaculture | Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) | University of Miami".sharkresearch.rsmas.miami.edu.Retrieved2018-04-02.

- ^Laville, Sandra (2019-11-06)."Dumped fishing gear is biggest plastic polluter in ocean, finds report".The Guardian.Retrieved2022-05-10.

- ^Magazine, Smithsonian; Kindy, David."With Ropes and Nets, Fishing Fleets Contribute Significantly to Microplastic Pollution".Smithsonian Magazine.Retrieved2022-05-10.

- ^Worm, Boris; et al. (2006-11-03). "Impacts of Biodiversity Loss on Ocean Ecosystem Services".Science.314(5800): 787–790.Bibcode:2006Sci...314..787W.doi:10.1126/science.1132294.PMID17082450.S2CID37235806.

- ^Juliet Eilperin (2 November 2006)."Seafood Population Depleted by 2048, Study Finds".The Washington Post.

- ^Observations: Oceanic Climate Change and Sea LevelArchived2017-05-13 at theWayback MachineIn:Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis.Contribution of Working Group I to theFourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.(15 MB).

- ^Doney, S. C. (March 2006)."The Dangers of Ocean Acidification"(PDF).Scientific American.294(3): 58–65.Bibcode:2006SciAm.294c..58D.doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0306-58.PMID16502612.

- ^US EPA, OAR (2015-04-07)."Climate Action Benefits: Freshwater Fish".US EPA.Retrieved2020-04-06.

- ^Weatherdon, Lauren V.; Magnan, Alexandre K.; Rogers, Alex D.; Sumaila, U. Rashid; Cheung, William W. L. (2016)."Observed and Projected Impacts of Climate Change on Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture, Coastal Tourism, and Human Health: An Update".Frontiers in Marine Science.3.doi:10.3389/fmars.2016.00048.ISSN2296-7745.

- ^Cheung, W.W.L.; et al. (October 2009).Redistribution of Fish Catch by Climate Change. A Summary of a New Scientific Analysis(PDF).Sea Around Us(Report). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-26.

- ^abcManuel Barange; Tarûb Bahri; Malcolm C. M. Beveridge; K. L. Cochrane; S. Funge Smith; Florence Poulain, eds. (2018).Impacts of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture: synthesis of current knowledge, adaptation and mitigation options.Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.ISBN978-92-5-130607-9.OCLC1078885208.

- ^Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), ed. (2022),"Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities",The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 321–446,doi:10.1017/9781009157964.006,ISBN978-1-00-915796-4,S2CID246522316,retrieved2022-04-06

Free content sources

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from afree contentwork. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken fromIn brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018,FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from afree contentwork. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken fromIn brief, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, 2018,FAO, FAO.