Font

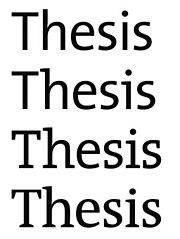

Inmetaltypesetting,afont(American English) orfount(Commonwealth English) is a particularsize, weight and styleof atypeface,defined as the set of fonts that share an overall design. For instance, the typefaceBauer Bodoni(shown in the figure) includes fonts "Roman"(or" regular "),"bold"and"italic";each of these exists in a variety ofsizes.

In the digital description of fonts (computer fonts), the terms "font" and "typeface" are often used interchangeably.[1]For example, when used in computers, each style is stored in a separate digitalfont file.

In both traditional typesetting and computing, the word "font" refers to the delivery mechanism of the typeface. In traditional typesetting, the font would be made from metal orwood type:to compose a page may require multiple fonts or even multiple typefaces.

Spelling and etymology

[edit]The wordfont(US) orfount(traditional UK; in any case pronounced/fɒnt/) derives fromMiddle Frenchfonte,meaning "cast iron".[2]The term refers to the process of casting metal type at atype foundry.The spellingfontis mainly used in the United States, whereasfountwas historically used in mostCommonwealthcountries.

Metal type

[edit]

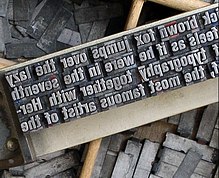

In a manual printing (letterpress) house the word "font" would refer to a complete set ofmetal typethat would be used totypesetan entire page. Upper- and lowercase letters get their names because of which case the metal type was located in for manual typesetting: the more distant upper case or the closer lower case. The same distinction is also referred to with the termsmajusculeandminuscule.

Unlike a digital typeface, a metal font would not include a single definition of each character, but commonly used characters (such as vowels and periods) would have more physical type-pieces included. A font when bought new would often be sold as (for example in a Roman alphabet) 12pt 14A 34a, meaning that it would be a size 12-pointfont containing 14 uppercase "A" s, and 34 lowercase "A" s.

The rest of the characters would be provided in quantities appropriate for thedistributionof letters in that language. Some metal type characters required in typesetting, such asdashes,spaces and line-height spacers, were not part of a specific font, but were generic pieces that could be used with any font.[3]Line spacing is still often called "leading",because the strips used for line spacing were made oflead(rather than the harder alloy used for other pieces). This spacing strip was made from lead because lead was a softer metal than the traditional forged metal type pieces (which waspart lead, antimony and tin) and would compress more easily when "locked up" in the printing "chase" (i.e. a carrier for holding all the type together).

In the 1880s–1890s, "hot lead" typesetting was invented, in which type was cast as it was set, either piece by piece (as in theMonotypetechnology) or in entire lines of type at one time (as in theLinotypetechnology).

Characteristics

[edit]In addition to the character height, when using the mechanical sense of the term, there are several characteristics which may distinguish fonts, though they would also depend on thescript(s) that the typeface supports. In Europeanalphabetic scripts,i.e.Latin,Cyrillic,andGreek,the main such properties are thestroke width, called weight,thestyle or angleand thecharacter width.

The regular or standard font is sometimes labeledroman,both to distinguish it fromboldorthinand fromitalicoroblique.The keyword for the default, regular case is often omitted for variants and never repeated, otherwise it would beBulmer regular italic,Bulmer bold regularand evenBulmer regular regular.Romancan also refer to the language coverage of a font, acting as a shorthand for "Western European".

Different fonts of the same typeface may be used in the same work for various degrees of readability andemphasis,or in a specific design to make it be of more visual interest.

Weight

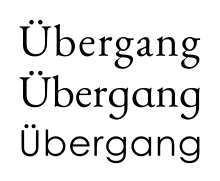

[edit]The weight of a particular font is the thickness of the character outlines relative to their height.

A typeface may come in fonts of many weights, from ultra-light to extra-bold or black; four to six weights are not unusual, and a few typefaces have as many as a dozen. Many typefaces for office, web and non-professional use come with a normal and a bold weight which are linked together. If no bold weight is provided, many renderers (browsers, word processors, graphic and DTP programs) support a bolder font by rendering the outline a second time at an offset, or smearing it slightly at a diagonal angle.

The base weight differs among typefaces; that means one font may appear bolder than another font. For example, fonts intended to be used in posters are often bold by default while fonts for long runs of text are rather light. Weight designations in font names may differ in regard to the actual absolute stroke weight or density of glyphs in the font.

Attempts to systematize a range of weights led to a numerical classification first used in 1957 byAdrian Frutigerwith theUniverstypeface: 35Extra Light,45Light,55MediumorRegular,65Bold,75Extra Bold,85Extra Bold,95Ultra BoldorBlack. Deviants of these were the "6 series" (italics), e.g.46 Light Italicsetc., the "7 series" (condensed versions), e.g.57 Medium Condensedetc., and the "8 series" (condensed italics), e.g. 68Bold Condensed Italics. From this brief numerical system it is easier to determine exactly what a font's characteristics are, for instance "Helvetica 67" (HE67) translates to "Helvetica Bold Condensed".

Helveticahas a monoline design and all strokes increase in weight in bold.

Less monoline fonts likeOptimaandUtopiaincrease the weight of the thicker strokes more.

In all three designs, the curve on 'n' thins as it joins the left-hand vertical.

The first algorithmic description of fonts was made byDonald Knuthin his 1986Metafontdescription language and interpreter.

TheTrueTypefont format introduced a scale from 100 through 900, which is also used inCSSandOpenType,where 400 is regular (roman or plain).

TheMozilla Developer Networkprovides the following rough mapping[4]to typical font weight names:

| Names | Numerical values |

|---|---|

| Thin / Hairline | 100

|

| Ultra-light / Extra-light | 200

|

| Light | 300

|

| Normal / regular | 400

|

| Medium | 500

|

| Semi-bold / Demi-bold | 600

|

| Bold | 700

|

| Extra-bold / Ultra-bold | 800

|

| Heavy / Black | 900

|

| Extra-black / Ultra-black | 950

|

Font mapping varies by font designer. A good example is Bigelow and Holmes'sGo Gofont family. In this family, the "fonts have CSS numerical weights of 400, 500, and 600. Although CSS specifies 'Bold' as a 700 weight and 600 as Semibold or Demibold, the Go numerical weights match the actual progression of the ratios of stem thicknesses: Normal:Medium = 400:500; Normal:Bold = 400:600".[5]

The termsnormal,regularandplain(sometimesbook) are used for the standard-weight font of a typeface. Where both appear and differ,bookis often lighter thanregular,but in some typefaces it is bolder.

Before the arrival of computers, each weight had to be drawn manually. As a result, many older multi-weight families such asGill SansandMonotype Grotesquehave considerable differences in weights from light to extra-bold. Since the 1980s, it has become common to use automation to construct a range of weights as points along a trend,multiple masteror other parameterized font design. This means that many modern digital fonts such asMyriadandTheSansare offered in a large range of weights which offer a smooth and continuous transition from one weight to the next, although some digital fonts are created with extensive manual corrections.

As digital font design allows more variants to be created faster, a common development in professional font design is the use of "grades": slightly different weights intended for different types of paper and ink, or printing in a different region with different ambient temperature and humidity.[6][7][8]For example, a thin design printed on book paper and a thicker design printed onhigh-gloss magazine papermay come out looking identical, since in the former case the ink will soak and spread out more. Grades are offered with characters having the same width on all grades, so that a change of printing materials does not affect copy-fit.[9][10]Grades are common on serif fonts with their finer details.

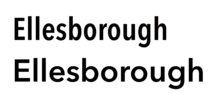

Fonts in which the bold and non-bold letters have the same width are "duplexed".

Style

[edit]Slope

[edit]

In European typefaces, especially Roman ones, a slope or slanted style is used to emphasize important words. This is calleditalictypeoroblique type.These designs normally slant to the right in left-to-right scripts. Oblique styles are often called italic, but differ from "true italic" styles.

Italic styles are more flowing than the normal typeface, approaching a morehandwritten,cursivestyle, possibly usingligaturesmore commonly or gainingswashes. Although rarely encountered, a typographic face may be accompanied by a matching calligraphic face (cursive,script), giving an exaggeratedly italic style.

In many sans-serif and some serif typefaces, especially in those with strokes of even thickness, the characters of the italic fonts are onlyslanted,which is often done algorithmically, without otherwise changing their appearance. Suchobliquefonts are not true italics, because lowercase letter shapes do not change, but they are often marketed as such. Fonts normally do not include both oblique and italic styles: the designer chooses to supply one or the other.

Since italic styles clearly look different to regular (roman) styles, it is possible to have "upright italic" designs that take a more cursive form but remain upright;Computer Modernis an example of a font that offers this style. In Latin-script countries, upright italics are rare but are sometimes used in mathematics or in complex documents where a section of text already in italics needs a "double italic" style to add emphasis to it. For example, the Cyrillicminuscule"т" may look like a smaller form of itsmajuscule"Т" or more like a roman small "m" as in its standard italic appearance; in this case, the distinction between styles is also a matter of local preference.

Other style attributes

[edit]In Frutiger's nomenclature the second digit for upright fonts is a 5, for italic fonts a 6 and for condensed italic fonts an 8.

The twoJapanese syllabaries,katakanaandhiragana,are sometimes seen as two styles or typographic variants of each other, but usually are considered separate character sets as a few of the characters have separatekanjiorigins and the scripts are used for different purposes. Thegothicstyleof the roman script with broken letter forms, on the other hand, is usually considered a mere typographic variant.

Cursive-only scripts such asArabicalso have different styles, in this case for exampleNaskhandKufic,although these often depend on application, area or era.

There are other aspects that can differ among font styles, but more often these are considered intrinsic features of the typeface.[citation needed]These include the look of digits (text figures) and the minuscules, which may be smaller versions of the capital letters (small caps) although the script has developed characteristic shapes for them. Some typefaces do not include separate glyphs for the cases at all, thereby abolishing thebicamerality.While most of these use uppercase characters only, some labeledunicaseexist which choose either the majuscule or the minuscule glyph at a common height for both characters.

Titling fontsare designed for headlines and displays, and have stroke widths optimized for large sizes.

Width

[edit]

Some typefaces include fonts that vary the width of the characters (stretch), although this feature is usually rarer than weight or slope. Narrower fonts are usually labeledcompressed,condensedornarrow.In Frutiger's system, the second digit of condensed fonts is a 7. Wider fonts may be calledwide,extendedorexpanded. Both can be further classified by prependingextra,ultraor the like. Compressing a font design to a condensed weight is a complex task, requiring the strokes to be slimmed down proportionally and often making the capitals straight-sided.[a][11]It is particularly common to see condensed fonts for sans-serif and slab-serif families, since it is relatively practical to modify their structure to a condensed weight. Serif text faces are often only issued in the regular width.

These separate fonts have to be distinguished from techniques that alter theletter-spacingto achieve narrower or smaller words, especially forjustified text alignment.

Most typefaces either haveproportionalormonospaced(for example, those resemblingtypewriteroutput) letter widths, if the script provides the possibility. Some superfamilies include both proportional and monospaced fonts. Some fonts also provide bothproportional and fixed-width(tabular) digits, where the former usually coincide with lowercase text figures and the latter with uppercaselining figures.

The width of a font will depend on its intended use.Times New Romanwas designed with the goal of having small width, to fit more text into a newspaper. On the other hand,Palatinohas large width to increase readability. The "billing block"on a movie poster often uses extremely condensed type in order to meet union requirements on the people who must be credited and the font height relative to the rest of the poster.[12]

Optical size

[edit]

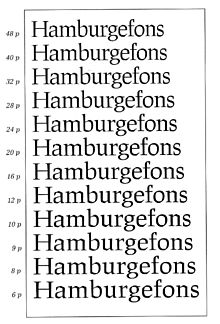

Optical sizes refer to different versions of the same typefaces optimised for specific font sizes.[13][14][15]For instance, thinner stroke weight might be used if a font style is intended forlarge-size display use,orink trapsmight be added to the design if it is to be printed at small size on poor-quality paper.[16]This was a natural feature in the metal type period for most typefaces, since each size would be cut separately and made to its own slightly different design.[17][18][19]As an example of this, experienced Linotype designerChauncey H. Griffithcommented in 1947 that for a type he was working on intended for newspaper use, the 6 point size was not 50% as wide as the 12 point size,[b]but about 71%.[20]

Optical sizing declined in use aspantographengraving emerged, while phototypesetting and digital fonts further made printing the same font at any size simpler. A mild revival has taken place in recent years, although typefaces with optical sizes remain rare.[21][22][23][24]The recentvariable fonttechnology further allows designers to include an optical size axis for a typeface, which means end users can manually adjust optical sizing on a continuous scale.[13]Examples of variable fonts with such an axis areRoboto Flex[25]andHelvetica Now Variable.[26]

Optical sizes are more common for serif fonts, since their typically finer detail and higher contrast benefits more from being bulked up for smaller sizes and made less overpowering at larger ones.[18]Furthermore, it is often desirable for mathematical fonts (i.e., typefaces designed for typesetting mathematical equations) to have two optical sizes below "Regular",[27]typically for higher-order superscripts and subscripts which are very small in sizes. Examples of such mathematical fonts includeMinion Math[28]andMathTime 2.[29][30]

Naming convention

[edit]Naming schemes for optical sizes vary.[31]One such scheme, invented and popularised by Adobe, labels the variant designs by their typical usages (with the intended point sizes varying slightly by typefaces):

- Poster:Extremely large sizes, usually larger than 72 point

- Display:Large sizes, typically 19–72 point

- Subhead:Large text, typically about 14–18 point

- "Regular" or "Text":Usually leftunnamed,typically about 10–13 point

- Small Text (SmText):Typically about 8–10 point

- Caption:Very small, typically about 4–8 point

Other type designers and publishers might use different naming schemes. For instance, the smaller optical size ofHelvetica Nowis labelled "Micro",[32]while the display variant ofHoefler Textis called "Titling".[33]Another example isTimes,whose variants are labelled by their intended point sizes, such as Times Ten,[34]Times Eighteen,[35]and Times New Roman Seven.[36]

Variable fonts typically do not use any naming scheme, because the inclusion of an adjustable optical size axis means optical sizes are not released as separate products.

Metrics

[edit]

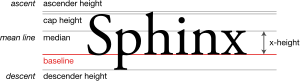

Font metricsrefers tometadataconsisting of numeric values relating to size and space in the font overall, or in its individual glyphs. Font-wide metrics includecap height(the height of the capitals),x-height(the height of the lowercase letters) andascenderheight,descenderdepth, and the fontbounding box.Glyph-level metrics include the glyph bounding box, the advance width (the proper distance between the glyph's initial pen position and the next glyph's initial pen position), and sidebearings (space that pads the glyph outline on either side). Many digital (and some metal type) fonts are able to bekernedso that characters can be fitted more closely; the pair "Wa" is a common example of this.

Some fonts, especially those intended for professional use, are duplexed: made with multiple weights having the same character width so that (for example) changing from regular to bold or italic does not affect word wrap.[37]Sabonas originally designed was a notable example of this. (This was a standard feature of the Linotype hot metal typesetting system with regular and italic being duplexed, requiring awkward design choices as italics normally are narrower than the roman.)

A particularly important basic set of fonts that became an early standard in digital printing was theCore Font Setincluded in thePostScriptprinting system developed by Apple and Adobe. To avoid paying licensing fees for this set, many computer companies commissioned "metrically compatible" knock-off fonts with the same spacing, which could be used to display the same document without it seeming clearly different.ArialandCentury Gothicare notable examples of this, being functional equivalents to the PostScript standard fontsHelveticaandITC Avant Garderespectively.[38][39][40][41][42]Some of these sets were created in order to be freely redistributable, for exampleRed Hat'sLiberation fontsand Google'sCroscore fonts,which duplicate the PostScript set and other common fonts used inMicrosoftsoftware such asCalibri.[43][better source needed]It is not a requirement that a metrically compatible design be identical to its origin in appearance apart from width.[44]

Serifs

[edit]Although most typefaces are characterised by their use ofserifs,there aresuperfamiliesthat incorporate serif (antiqua) andsans-serif(grotesque) or even intermediateslab serif(Egyptian) or semi-serif fonts with the same base outlines.

A more common font variant, especially of serif typefaces, is that of alternate capitals. They can haveswashesto go with italic minuscules or they can be of a flourish design for use asinitials(drop caps).

Character variants

[edit]

Typefaces may be made in variants for different uses. These may be issued as separate font files, or the different characters may be included in the same font file if the font is a modern format such asOpenTypeand the application used can support this.[45][46][47]

Alternative characters are often called stylistic alternates. These may be switched on to allow users more flexibility to customise the typeface to suit their needs. The practice is not new: in the 1930s,Gill Sans,a British design, was sold abroad with alternative characters to make it resemble typefaces such asFuturapopular in other countries, whileBembofrom the same period has two shapes of "R": one with a stretched-out leg, matching its fifteenth-century model, and one less-common shorter version.[48]With modern digital fonts, it is possible to group related alternative characters into stylistic sets, which may be turned on and off together. For example, inWilliams Caslon Text,a revival of the 18th centuryCaslontypeface, the default italic forms have many swashes matching the original design. For a more spare appearance, these can all be turned off at once by engaging stylistic set 4.[49]Junicode,intended for academic publishing, uses ss15 to enable avariant form of "e"used in medieval Latin. A corporation commissioning a modified version of a commercial computer font for their own use, meanwhile, might request that their preferred alternates be set to default.

It is common for typefaces intended for use in books for young children to use simplified, single-storey forms of the lowercase lettersaandg(sometimes alsot,y,land the digit4); these may be calledinfantorschoolbookalternates. They are traditionally believed to be easier for children to read and less confusing as they resemble the forms used in handwriting.[50]Often schoolbook characters are released as a supplement to popular families such asAkzidenz-Grotesk,Gill SansandBembo;a well-known font intended specifically for school use isSassoon Sans.[51][52]

Besides alternate characters, in the metal type eraThe New York Timescommissioned custom condensed single sorts for common long names that might often appear in news headings, such as"Eisenhower","Chamberlain"or"Rockefeller".[53]

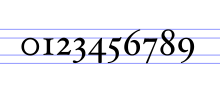

Digits

[edit]

Fonts can have multiple kinds of digits, including, as described above, proportional (variable width) and tabular (fixed width) as well as lining (uppercase height) and text (lowercase height) figures. They may also include separate shapes for superscript and subscript digits. Professional computer fonts may include even more complex settings for typesetting digits, such as digits intended to match the height of small caps.[54][55]In addition, some fonts such as Adobe's Acumin andChristian Schwartz'sNeue Haas Groteskdigitisation offer two heights of lining (uppercase height) figures: one slightly lower than cap height, intended to blend better into continuous text, and one at exactly the cap height to look better in combination with capitals for uses such as UK postcodes.[56][57][58][59]With the OpenType format, it is possible to bundle all these into a single digital font file, but earlier font releases may have only one type per file.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^"Typefaces vs. fonts: here's how they're different".Shaping Design Blog.2021-11-09.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-06-29.Retrieved2023-06-14.

- ^Douglas Harper (2001)."font".Online Etymology Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-06-29.Retrieved2013-07-19.

- ^"Basic Letterpress Tools".Archived fromthe originalon 2008-12-24.Retrieved2008-12-07.

- ^"font-weight".Mozilla Developer Network.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-05-25.Retrieved2017-07-04.

- ^"Go fonts".GOLang.org(Press release). Google.Archivedfrom the original on 14 August 2021.Retrieved22 August2019.

- ^Butterick, Matthew."Equity: specimen & manual"(PDF).MBType.Archived(PDF)from the original on 28 August 2021.Retrieved7 August2015.

- ^"Fancy Instagram Fonts Generator 😍(𝓬𝓸𝓹𝔂 ⒶⓃⒹ 𝓅𝒶𝓈𝓉𝑒)".SEOHorizon.Archivedfrom the original on Feb 2, 2024.

- ^"Benton Modern".Webtype.Font Bureau. Archived fromthe originalon 12 August 2015.Retrieved7 August2015.

- ^Porchez, Jean François (January 25, 2012)."Equity".Typographica.Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2021.Retrieved13 July2015.

- ^Peters, Yves (April 4, 2017)."Inside the fonts: grading Bennet".Type Network.Archivedfrom the original on 24 November 2021.Retrieved25 September2018.

- ^Frere-Jones, Tobias(2015)."Typeface Mechanics: 002".Frere-Jones Type.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2021.Retrieved27 December2017.

If we change that interval of white space without changing anything else, this doesn't add up any more. Or more accurately, it adds up to something we didn't want, if we had hoped to keep a consistent darkness. The proportion of black and white has changed, and that is where we get our sense of light and dark, not from the measure of any single element...So when we just put the weights and spaces where they look right, we create a relationship that is neither arithmetic nor geometric but somewhere between. Our eyes are perpetually tough customers, and rarely accept the simplest solution...Weight will crowd together according to the angle of intersection, with the problem getting more acute as the angle gets more acute. It's why type designers will take a deep breath before starting a Compressed Extra Bold version of something, or why they might openly swear at the capital W.

- ^Schott, Ben (February 23, 2013)."Assembling the Billing Block".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on December 1, 2017.RetrievedMarch 1,2017.

- ^ab"Choosing typefaces that have optical sizes - Google Fonts".Archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"What is optical sizing and how can it help your brand? - Monotype".6 April 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"Identifont - Optical sizes".Archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^Reynolds, Dan (21 May 2012)."How To Choose The Right Face For A Beautiful Body".Smashing.Archivedfrom the original on 19 November 2021.Retrieved13 September2015.

- ^Carter, Harry(1937)."Optical scale in type founding".Typography.4.Archived fromthe originalon 8 March 2021.Retrieved15 September2019.

- ^abFrere-Jones, Tobias."MicroPlus".Frere-Jones Type.Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2021.Retrieved1 December2015.

- ^"Requiem features".Hoefler & Frere-Jones.Archivedfrom the original on 11 July 2017.Retrieved2 July2015.

- ^Tracy, Walter.Letters of Credit.pp. 52–55.

- ^Ahrens and Mugikura."Size-specific Adjustments to Type Designs".Just Another Foundry.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-09-04.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^Coles, Stephen."Book Review: Size-specific Adjustments to Type Designs".Typographica.Archivedfrom the original on 5 December 2021.Retrieved21 November2014.

- ^Kupferschmid, Indra (13 May 2012)."Multi-axes type families".kupferschrift.Archivedfrom the original on 7 August 2021.Retrieved8 December2014.

- ^"Trianon".Production Type.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2021.Retrieved2 July2015.

- ^"Roboto Flex – Variable Fonts".Archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"Helvetica Now Variable – Variable Fonts".Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-14.Retrieved2023-04-14.

- ^"Fonts for Mathematics"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"typoma".17 May 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-02.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"mtpro2 - PCTeXWeb".Archivedfrom the original on 2023-04-17.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"The 68 individually designed fonts"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^Slimbach, Souser, Slye, Twardoch."Arno Pro specimen"(PDF).Adobe. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 August 2014.Retrieved3 July2015.

- ^"Helvetica Now Font".Archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"Hoefler Titling".Hoefler & Frere-Jones.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-05-13.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"Linotype Times Ten".MyFonts.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-08.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"Linotype Times Eighteen".MyFonts.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-03-08.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^"Times New Roman Seven".Archivedfrom the original on 2021-12-22.Retrieved2023-05-13.

- ^Butterick, Matthew."Concourse specimen pdf".MBType.Archived(PDF)from the original on 11 August 2021.Retrieved7 August2015.

- ^Shaw, Paul."Arial Addendum no. 3".Blue Pencil.Archivedfrom the original on 9 December 2021.Retrieved1 July2015.

- ^Shaw (& Nicholas)."Arial addendum no. 4".Blue Pencil.Archivedfrom the original on 9 December 2021.Retrieved1 July2015.

- ^McDonald, Rob."Some history about Arial".Paul Shaw Letter Design.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2021.Retrieved22 May2015.

- ^Haley, Allan (May–June 2007)."Is Arial Dead Yet?".Step Inside Design.Archived fromthe originalon July 19, 2011.Retrieved2011-05-11.

- ^"Type Designer Showcase: Robin Nicholas – Arial".Monotype Imaging. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-14.Retrieved2011-05-10.

- ^"Liberation Fonts".Fedora.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-02-15.Retrieved2016-01-15.

- ^Schwartz, Christian."DB".Schwartzco.Archivedfrom the original on 22 April 2021.Retrieved16 July2015.

- ^"What's OpenType?".Hoefler & Frere-Jones.Archivedfrom the original on 30 March 2019.Retrieved7 August2015.

- ^Peters, Yves (24 October 2014)."Why a better OpenType UI matters".i love typography.Archivedfrom the original on 14 August 2019.Retrieved14 August2015.

- ^Benedek, Andy."Calligraphic-style Fonts: Problems and Solutions"(PDF).The Edward Johnston Foundation Journal:2–12.Archived(PDF)from the original on 25 January 2021.Retrieved21 September2023.

- ^"Specimen Book of Monotype Printing Types (photograph)".Flickr.6 January 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2021.Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^Berkson, William."Williams Caslon Text features manual"(PDF).Font Bureau.Archived(PDF)from the original on 1 March 2021.Retrieved7 August2015.

- ^Walker, Sue; Reynolds, Linda (1 January 2003). "Serifs, sans serifs and infant characters in children's reading books".Information Design Journal.11(3): 106–122.doi:10.1075/idj.11.2.04wal.

- ^Coles, Stephen (20 March 2016)."Design Museum".Fonts In Use.Archivedfrom the original on 14 August 2019.Retrieved13 July2016.

- ^"Bembo Infant".MyFonts.Archivedfrom the original on 27 October 2019.Retrieved1 May2016.

- ^Dunlap, David (23 June 2016)."1952 | 'Eisenhower,' a True Campaign Logo".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2021.Retrieved20 August2017.

- ^Shinn, Nick."Shinntype Modern Suite specification"(PDF).Shinntype. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 25 February 2021.Retrieved16 October2015.

- ^"Paciencias specification".Typographias.Archivedfrom the original on 17 November 2019.Retrieved16 October2015.

- ^"Neue Haas Grotesk".The Font Bureau, Inc. p. Introduction.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-05-09.Retrieved2015-10-16.

- ^"Neue Haas Grotesk - Font News".Linotype.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-09-05.Retrieved2013-09-21.

- ^"Schwartzco Inc".Christianschwartz.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-04-20.Retrieved2013-09-21.

- ^Slimbach, Robert."Acumin - usage".Typekit.Adobe Systems.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2016.Retrieved16 October2015.

Notes

[edit]- ^Simply digitally compressing the font produces ugly results, since it narrows the vertical strokes but not the horizontals.

- ^In metal type, thepoint sizeof the font describes theheight(not width) of the metalbodyon which thetypeface's characters were cast. The typeface was the "Falcon" design byWilliam Addison Dwiggins,ultimately never issued.

Further reading

[edit]- Blackwell, Lewis.20th Century Type.Yale University Press: 2004.ISBN0-300-10073-6.

- Fiedl, Frederich, Nicholas Ott and Bernard Stein.Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History.Black Dog & Leventhal: 1998.ISBN1-57912-023-7.

- Lupton, Ellen.Thinking with Type: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, Editors, & Students,Princeton Architectural Press: 2004.ISBN1-56898-448-0.

- Headley, Gwyn.The Encyclopaedia of Fonts.Cassell Illustrated: 2005.ISBN1-84403-206-X.

- Macmillan, Neil.An A–Z of Type Designers.Yale University Press: 2006.ISBN0-300-11151-7.