Francisco Zúñiga

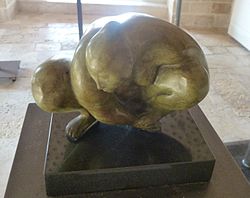

José Jesús Francisco Zúñiga Chavarría(December 27, 1912 – August 9, 1998[1]) was aCosta Rican-bornMexicanartist, known both for his painting and his sculpture.[2]Journalist Fernando González Gortázar lists Zúñiga as one of the 100 most notable Mexicans of the 20th century,[3]while theEncyclopædia Britannicacalls him "perhaps the best sculptor" of the Mexican political modern style.[4]

Biography[edit]

Zúñiga was born in Guadalupe, Barrio de San José, Costa Rica on December 27, 1912, to Manuel Maria Zúñiga and María Chavarría, both sculptors. His father worked as a sculptor of religious figures, and in stone work. His artistic inclinations began early and by the age of twelve had already read books on the history of art, artistic anatomy and the life of various Renaissance painters. At age fifteen he began working in his father's shop. This experience sensitized him to shape and spaces.[5][6][7]In 1926 he enrolled in the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Mexico, but left the following year to continue on his own. As part of his self-study, he studiedGerman Expressionismand the writings of Alexander Heilmayer, through which he learned of the work of two French sculptors,Aristide MaillolandAuguste Rodin,coming to appreciate the idea of subordinating technique to expression.[5]

Zúñiga's painting and sculpting work began receiving recognition in 1929.[6]His first stone sculpture won second prize at the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes. In the following two years continued to win top prizes at this event. This work made critics recommend him for study abroad.[5]He won first prize in a 1935 Latin American sculpture competition, the Salón de Escultura en Costa Rica, for his stone sculptureLa maternidad,[8]but the work caused controversy and the government rescinded its award.[5]In the 1930s, he began to research pre Hispanic art and its importance to contemporary Latin American art, as well as what was happening artistically in Mexico.[6]The scholarship never materialized so various colleagues organized his first individual exhibition in Costa Rica. The earnings from this endeavor earned his passage toMexico City.[5]In 1936 he immigrated to Mexico permanently.[9][10]

In the capital, his first contact withManuel Rodríguez Lozano,who opened his library to Zúñiga.[5]He did some formal study at La Escuela de Talla Directa, working with Guillermo Ruiz, sculptorOliverio Martínez,and painter Rodríguez Lozano.[7]In 1937 he worked as an assistant to Oliverio Martínez on theMonument to the Revolution,the re-imagined building that had begun as the Federal Legislative Palace conceived during the regime ofPorfirio Díaz.[5][6]In 1938, he took a faculty position atLa Esmeralda;he remained at that position until retiring in 1970.[9][11]In 1958 he was awarded the first prize in sculpture from the MexicanNational Institute of Fine Arts.[8]

In the 1940s, theNew York Museum of Modern Artacquired the sculpture Cabeza de niño totonaca and theMetropolitan Museum of Artrequested two of his drawings. He also helped to found the Sociedad Mexicana de Escultores and received commissions in various parts of Mexico.[5]

In 1947, he married Elena Laborde, a painting student. They had three children, Ariel, Javier and Marcela.[5]

In 1949, he was part of the founding board of theSalón de la Plástica Mexicana,and in 1951, he joined the Frente Nacional de Artes Plástica ofFrancisco Goitia.[5]

Major individual exhibitions during his career include the Bernard Lewin Gallery in Los Angeles in 1965, a retrospective at theMuseo de Arte Modernoin 1969 and various exhibitions in Europe in the 1980s.[5]

In 1971, he received the Acquisition Prize at the 1971 Biennial of Open Air Sculpture of Middelheim inAntwerp,Belgium.In 1975 twenty of his drawings with the Misrachi Gallery obtained the silver medal at the International Book Exposition of Leipzig. In the 1980s, he was named an Academic of the Accademia delle Arte e del Lavoro in Parma, Italy. In Mexico he won the Elías Sourasky Prize.[5]

In 1984 he won the first Kataro Takamura Prize of the Third Biennial of Sculpture in Japan.[5]

He became a Mexican citizen in 1986, fifty years after his arrival in the country.[5][6]

In 1992 he received thePremio Nacional de Arte,and in 1994, thePalacio de Bellas Artesheld a tribute to his career.[5]

Near the end of his life, illness left him nearly blind, which caused him to shift his artistic work to terra cotta, using his hands to create the lines.[5]

Works[edit]

Zúñiga created over thirty five public sculptures, such as the monument to poetRamón López Velardeinthe city of Zacatecasand others dedicated to Mexican heroes. In the 1940s he created two sculpture forChapultepec Park,Muchachas corriendo and Física nuclear. In 1984 he created a group of sculptures called Tres generaciones for the city ofSendai, Japan.During his lifetime, these were considered his most important works. Since then, they have become secondary to his other sculpting.[5][6]

He stated that he preferred figurative art because he found the human figure to be “the most important aspect of the world around (him)”. He was also strongly influenced by pre Hispanic art, spending significant time sketching pieces in museums, along with images of women in traditional markets, feeling that they represented maternity and familial responsibility.[5]

Museums holding his works in their permanent collections include theSan Diego Museum of Art,[12]theNew Mexico Museum of Art,[13]theMetropolitan Museum of Artand theMuseum of Modern Artin New York, theMuseo de Arte Modernoin Mexico City, theDallas Museum of Art,thePhoenix Art Museum,thePonce Museum of Artin Puerto Rico, and theHirshhorn Museum and Sculpture GardeninWashington, D.C.[7]

- Seated Yucatan Woman

- Mother and Daughter Seated(1971), San Diego

References[edit]

- ^"Biography".Archived fromthe originalon 2018-02-26.Retrieved2016-07-25.

- ^"Costa Rican Enrichment",Washington Post,June 18, 1993.

- ^"Mis cien mexicanos del siglo XX".La Jornada,January 30, 2000.

- ^Latin American art,Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrVision de México y sus Artistas(in Spanish and English). Vol. I. Mexico City: Qualitas. 2001. pp. 228–230.ISBN968-5005-58-3.

- ^abcdefGuillermo Tovar de Teresa (1996).Repertory of Artists in Mexico: Plastic and Decorative Arts.Vol. III. Mexico City: Grupo Financiero Bancomer. p. 442.ISBN968-6258-56-6.

- ^abcBiographyArchived2012-02-08 at theWayback Machine,Medicine Man Gallery.

- ^abBiografia de Francisco Zúñiga,Biografias y Vidas.

- ^ab"Con su obra, Francisco Zúñiga retorna a su natal Costa Rica".La Jornada,January 15, 1999.

- ^"Muere destacado escultor mexicano Francisco Zuniga".Fort Worth Star-Telegram,August 14, 1998.

- ^Biography,Joan Cawley gallery.

- ^May S. Marcy Sculpture Court and GardenArchived2007-10-06 at theWayback Machine,San Diego Museum of Art.

- ^"Searchable Art Museum".New Mexico Museum of Art.Retrieved11 August2013.

Books[edit]

- Anguiano, Raúl; Moyssén Echeverría, Xavier; Sebastián, Enrique Carbajal (1998),Homenaje al maestro Francisco Zúñiga: (1912 - 1998),Academia de Artes,ISBN968-7292-12-1.

- Brewster, Jerry (1984),Zúñiga,Alpine Fine Arts,ISBN0-88168-007-9.

- Echeverria, Carlos Francisco (1981),Zúñiga: An Album of His Sculptures,Hacker Art Books,ISBN978-968-7047-03-4.

- Cardona Pena, Alfredo (1997),Francisco Zúñiga: Viaje poetico,Editorial Universidad Estatal a Distancia,ISBN978-9977-64-899-6.

- Ferrero, Luis (1985),Zúñiga, Costa Rica: Colección Daniel Yankelewitz,Editorial Costa Rica,ISBN9977-23-160-5.

- Paquet, Marcel (1989),Zúñiga: La abstracción sensible,El Taller del Equilibrista,ISBN968-6285-24-5.

- Reich, Sheldon (1981),Francisco Zúñiga, Sculptor: Conversations and Interpretations,Univ. of Arizona Press,ISBN978-0-8165-0665-1.

- Rodriguez Prampolini, Ida (2002),La obra de Francisco Zúñiga, canon de belleza americana,Sinc, S.A. de C.V / Albedrio,ISBN978-970-9027-07-5.

- Zúñiga, Ariel (2001),Francisco Zúñiga: Travel sketches 1,Sinc, S.A. de C.V / Albedrio,ISBN978-970-9027-05-1.

- Zúñiga, Ariel (1999),Francisco Zúñiga, Catalogo Razonado, Volumen I: Escultura / Catalogue Raisonné, Volume I: Sculpture (1923-1993),Sinc, S.A. de C.V / Albedrio,ISBN978-970-9027-02-0.

- Zúñiga, Ariel (2003),Francisco Zúñiga, Catalogo Razonado, Vol. II: Oleos, estampas y reproducciones / Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. II: Oil Paintings, prints and reproductions,Sinc, S.A. de C.V / Albedrio,ISBN978-970-9027-08-2.

- Zúñiga, Ariel (2007),Francisco Zúñiga Catalogo Razonado / Catalogue Raisonné Volume III (Drawings 1927–1970),Sinc, S.A. de C.V / Albedrio,ISBN978-970-9027-10-5.

- Zúñiga, Ariel (2007),Francisco Zúñiga Catalogo Razonado / Catalogue Raisonné Volume IV (Drawings 1971–1989),Sinc, S.A. de C.V / Albedrio,ISBN978-970-9027-11-2.

Additional sources[edit]

- Nieto Sua, Rosa Amparo (1983),Francisco Zúñiga and the Mexican tradition,M.A. thesis, Queens College, New York.

- Ruiz de Icaza, Maru (1998), "Francisco Zúñiga: sus mujeres indígenas se asentaron en el ex Palacio del Arzobispo",Actual,5(52): 68.

- Sánchez Ambriz, Mary Carmen (1998), "Francisco Zúñiga, 1912-1998; In memoriam",Siempre!,45(2357): 61.

- Ureña Rib, Fernando (2007),La sostenida maestría de Francisco Zúñiga.

- Van Rheenen, Erin (2007),Living Abroad in Costa Rica,Avalon Travel Publishing,ISBN978-1-56691-652-3.

External links[edit]

- Francisco Zúñiga 1912–1998.Artist's web site maintained by Fundación Zúñiga Laborde A.C.

- Francisco Zúñiga woodcuts