Gabbro

Gabbro(/ˈɡæbroʊ/GAB-roh) is aphaneritic(coarse-grained and magnesium- and iron-rich),maficintrusiveigneous rockformed from the slow coolingmagmainto aholocrystallinemass deep beneath theEarth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is chemically equivalent to rapid-cooling, fine-grainedbasalt.Much of the Earth'soceanic crustis made of gabbro, formed atmid-ocean ridges.Gabbro is also found asplutonsassociated with continentalvolcanism.Due to its variant nature, the termgabbromay be applied loosely to a wide range of intrusive rocks, many of which are merely "gabbroic". By rough analogy, gabbro is tobasaltasgraniteis torhyolite.

Etymology

[edit]The term "gabbro" was used in the 1760s to name a set of rock types that were found in theophiolitesof theApennine Mountainsin Italy.[1]It was named afterGabbro,a hamlet nearRosignano MarittimoinTuscany.Then, in 1809, the German geologistChristian Leopold von Buchused the term more restrictively in his description of these Italian ophiolitic rocks.[2]He assigned the name "gabbro" to rocks that geologists nowadays would more strictly call "metagabbro" (metamorphosedgabbro).[3]

Petrology

[edit]

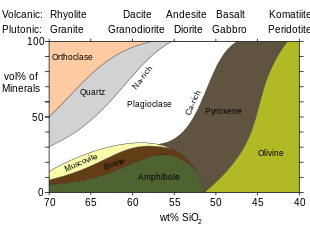

Gabbro is a coarse-grained (phaneritic)igneous rockthat is relatively low insilicaand rich in iron, magnesium, and calcium. Such rock is described asmafic.Gabbro is composed ofpyroxene(mostly clinopyroxene) and calcium-richplagioclase,with minor amounts ofhornblende,olivine,orthopyroxene andaccessory minerals.[4]With significant (>10%) olivine or orthopyroxene it is classified as olivine gabbro or gabbronorite respectively. Where present, hornblende is typically found as a rim aroundaugitecrystals or as large grains enclosing smaller grains of other minerals (poikiliticgrains).[5][6]

Geologists use rigorous quantitative definitions to classify coarse-grained igneous rocks, based on the mineral content of the rock. For igneous rocks composed mostly of silicate minerals, and in which at least 10% of the mineral content consists ofquartz,feldspar,orfeldspathoidminerals, classification begins with theQAPF diagram.The relative abundances of quartz (Q),alkali feldspar(A), plagioclase (P), and feldspathoid (F), are used to plot the position of the rock on the diagram.[7][8][9]The rock will be classified as either agabbroidor adioritoidif quartz makes up less than 20% of the QAPF content, feldspathoid makes up less than 10% of the QAPF content, and plagioclase makes up more than 65% of the total feldspar content. Gabbroids are distinguished from dioritoids by ananorthite(calcium plagioclase) fraction of their total plagioclase of greater than 50%.[10]

The composition of the plagioclase cannot easily be determinedin the field,and then a preliminary distinction is made between dioritoid and gabbroid based on the content of mafic minerals. A gabbroid typically has over 35% mafic minerals, mostly pyroxenes or olivine, while a dioritoid typically has less than 35% mafic minerals, which typically includes hornblende.[11]

Gabbroids form a family of rock types similar to gabbro, such asmonzogabbro,quartz gabbro,ornepheline-bearing gabbro.Gabbro itself is more narrowly defined, as a gabbroid in which quartz makes up less than 5% of the QAPF content, feldspathoids are not present, and plagioclase makes up more than 90% of the feldspar content. Gabbro is distinct fromanorthosite,which contains less than 10% mafic minerals.[12][7][8]

Coarse-grained gabbroids are produced by slow crystallization ofmagmahaving the same composition as thelavathat solidifies rapidly to form fine-grained (aphanitic)basalt.[7][8]

Subtypes

[edit]There are a number of subtypes of gabbro recognized by geologists. Gabbros can be broadly divided into leucogabbros, with less than 35% mafic mineral content; mesogabbros, with 35% to 65% mafic mineral content; and melagabbros with more than 65% mafic mineral content. A rock with over 90% mafic mineral content will be classified instead as anultramafic rock.A gabbroic rock with less than 10% mafic mineral content will be classified as an anorthosite.[8][13]

A more detailed classification is based on the relative percentages of plagioclase, pyroxene, hornblende, and olivine. The end members are:[8][13]

- Normal gabbro (gabbrosensu stricto[8]) is composed almost entirely of plagioclase andclinopyroxene(typically augite), with less than 5% each of hornblende, olivine, ororthopyroxene.

- Noriteis composed almost entirely of plagioclase andorthopyroxene,with less than 5% each of hornblende, clinopyroxene, or olivine.

- Troctoliteis composed almost entirely of plagioclase and olivine, with less than 5% each of pyroxene or hornblende.

- Hornblende gabbrois composed almost entirely of plagioclase and hornblende, with less than 5% each of pyroxene or olivine.

Gabbros intermediate between these compositions are given names such asgabbronorite(for a gabbro intermediate between normal gabbro and norite, with almost equal amounts of clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene) or olivine gabbro (for a gabbro containing significant olivine, but almost no clinopyroxene or hornblende). A rock similar to normal gabbro but containing more orthopyroxene is called an orthopyroxene gabbro, while a rock similar to norite but containing more clinopyroxene is called a clinopyroxene norite.[8]

Gabbros are also sometimes classified as alkali or tholleiitic gabbros, by analogy withalkaliortholeiiticbasalts, of which they are considered the intrusive equivalents.[14]Alkali gabbro usually contains olivine, nepheline, oranalcime,up to 10% of the mineral content,[15]while tholeiitic gabbro contains both clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene, making it a gabbronorite.[14]

Gabbroids

[edit]Gabbroids (also known as gabbroic-rocks[8]) are a family of coarse-grained igneous rocks similar to gabbro:[10]

- Quartz gabbro contains 5% to 20% quartz in its QAPF fraction. One example is thecizlakiteatPohorjein northeastern Slovenia,[16]

- Monzogabbro contains 65% to 90% plagioclase out of its total feldspar content.

- Quartz monzogabbrocombines the features of quartz gabbro and monzogabbro. It contains 5% to 20% quartz in its QAPF fraction, and 65% to 90% of its feldspar is plagioclase.

- Foid-bearing gabbro contains up to 10% feldspathoids rather than quartz. "Foid" in the name is usually replaced by the specific feldspathoid that is most abundant in the rock. For example, anepheline-bearing gabbro is a foid-bearing gabbro in which the most abundant feldspathoid is nepheline.

- Foid-bearing monzogabbro resembles monzogabbro, but containing up to 10% feldspathoids in place of quartz. The same naming conventions apply as for foid-bearing gabbro, so that a gabbroid might be classified as aleucite-bearing monzogabbro.[8]

Gabbroids contain minor amounts, typically a few percent, of iron-titanium oxides such asmagnetite,ilmenite,andulvospinel.Apatite,zircon,andbiotitemay also be present as accessory minerals.[6]

Gabbro is generally coarse-grained, with crystals in the size range of 1 mm or larger. Finer-grained equivalents of gabbro are calleddiabase(also known asdolerite), although the termmicrogabbrois often used when extra descriptiveness is desired. Gabbro may be extremely coarse-grained topegmatitic.[8]Some pyroxene-plagioclasecumulatesare essentially coarse-grained gabbro,[17]and may exhibit acicular crystal habits.[18]

Gabbro is usuallyequigranularin texture, although it may also showophitic texture[6](with laths of plagioclase enclosed in pyroxene[19]).

Distribution

[edit]

Nearly all gabbros are found in plutonic bodies, and the term (as theInternational Union of Geological Sciencesrecommends) is normally restricted just to plutonic rocks, although gabbro may be found as a coarse-grained interiorfaciesof certain thick lavas.[20][21]Gabbro can be formed as a massive, uniform intrusion via in-situ crystallisation ofpyroxeneandplagioclase,or as part of alayered intrusionas acumulateformed by settling of pyroxene and plagioclase.[22] An alternative name for gabbros formed by crystal settling ispyroxene-plagioclase adcumulate.

Gabbro is much less common than more silica-rich intrusive rocks in thecontinental crustof the Earth. Gabbro and gabbroids occur in somebatholithsbut these rocks are relatively minor components of these very large intrusions because their iron and calcium content usually makes gabbro and gabbroid magmas too dense to have the necessary buoyancy.[23]However, gabbro is an essential part of the oceanic crust, and can be found in manyophiolitecomplexes as layered gabbro underlingsheeted dike complexesand overlyingultramaficrock derived from theEarth's mantle.These layered gabbros may have formed from relatively small but long-livedmagma chambersunderlyingmid-ocean ridges.[24]

Layered gabbros are also characteristic oflopoliths,which are large, saucer-shaped intrusions that are primarilyPrecambrianin age. Prominent examples of lopoliths include theBushveld Complexof South Africa, theMuskox intrusionof theNorthwest Territoriesof Canada, theRum layered intrusionof Scotland, theStillwater complexof Montana, and the layered gabbros nearStavanger,Norway.[25]Gabbros are also present instocksassociated withalkaline volcanismofcontinental rifting.[26]

Uses

[edit]Gabbro often contains valuable amounts ofchromium,nickel,cobalt,gold,silver,platinum,andcoppersulfides.[27][28][29]For example, theMerensky Reefis the world's most important source of platinum.[30]

Gabbro is known in the construction industry by the trade name ofblack granite.[31]However, gabbro is hard and difficult to work, which limits its use.[32]

The term "indigo gabbro" is used as a common name for a mineralogically-complex rock type often found in mottled tones of black and lilac-grey. It is mined in central Madagascar for use as a semi-precious stone. Indigo Gabbro can contain numerous minerals, including quartz and feldspar. Reports state that the dark matrix of the rock is composed of a mafic igneous rock, but whether this is basalt or gabbro is unclear.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Peridotite– Coarse-grained ultramafic igneous rock type

- Igneous differentiation– Geologic process in formation of some igneous rocks

- Fractional crystallisation– Process of rock formation

References

[edit]- ^Bortolotti, V. et al.Chapter 11: Ophiolites, Ligurides and the tectonic evolution from spreading to convergence of a Mesozoic Western Tethys segmentin F. Vai, G.P. and Martini, I.P. (editors) (2001)Anatomy of an Orogen: The Apennines and Adjacent Mediterranean Basins,Dordrecht, Springer Science and Business Media, p. 151.ISBN978-90-481-4020-6

- ^Bortolotti, V. et al.Chapter 11: Ophiolites, Ligurides and the tectonic evolution from spreading to convergence of a Mesozoic Western Tethys segmentin F. Vai, G.P. and Martini, I.P. (editors) (2001)Anatomy of an Orogen: The Apennines and Adjacent Mediterranean Basins,Dordrecht, Springer Science and Business Media, p. 152.ISBN978-90-481-4020-6

- ^Gabbroat SandAtlas geology blog. Retrieved on 2015-07-09.

- ^Allaby, Michael (2013). "gabbro".A dictionary of geology and earth sciences(Fourth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN9780199653065.

- ^Jackson, Julia A., ed. (1997). "gabbro".Glossary of geology(Fourth ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: American Geological Institute.ISBN0922152349.

- ^abcBlatt, Harvey; Tracy, Robert J. (1996).Petrology: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic(2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. p. 53.ISBN0716724383.

- ^abcLe Bas, M. J.; Streckeisen, A. L. (1991). "The IUGS systematics of igneous rocks".Journal of the Geological Society.148(5): 825–833.Bibcode:1991JGSoc.148..825L.CiteSeerX10.1.1.692.4446.doi:10.1144/gsjgs.148.5.0825.S2CID28548230.

- ^abcdefghij"Rock Classification Scheme - Vol 1 - Igneous"(PDF).British Geological Survey: Rock Classification Scheme.1:1–52. 1999.

- ^Philpotts, Anthony R.; Ague, Jay J. (2009).Principles of igneous and metamorphic petrology(2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 139–143.ISBN978-0-521-88006-0.

- ^abJackson 1997,"gabbroid".

- ^Blatt & Tracy 1996,p. 71.

- ^Jackson 1997,"gabbro".

- ^abPhilpotts & Ague 2009,p. 142.

- ^abAllaby 2013,"gabbro".

- ^Jackson 1997,"alkali gabbro".

- ^Le Maitre, R. W.; et al., eds., 2005,Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms,Cambridge Univ. Press, 2nd ed., p. 69,ISBN9780521619486

- ^Beard, James S. (1 October 1986). "Characteristic mineralogy of arc-related cumulate gabbros: Implications for the tectonic setting of gabbroic plutons and for andesite genesis".Geology.14(10): 848–851.Bibcode:1986Geo....14..848B.doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1986)14<848:CMOACG>2.0.CO;2.

- ^Nicolas, Adolphe; Boudier, Françoise; Mainprice, David (April 2016). "Paragenesis of magma chamber internal wall discovered in Oman ophiolite gabbros".Terra Nova.28(2): 91–100.Bibcode:2016TeNov..28...91N.doi:10.1111/ter.12194.S2CID130338632.

- ^Wager, L. R. (October 1961). "A Note on the Origin of Ophitic Texture in the Chilled Olivine Gabbro of the Skaergaard Intrusion".Geological Magazine.98(5): 353–366.Bibcode:1961GeoM...98..353W.doi:10.1017/S0016756800060829.S2CID129950597.

- ^Arndt, N.T.; Naldrett, A.J.; Pyke, D.R. (1 May 1977). "Komatiitic and Iron-rich Tholeiitic Lavas of Munro Township, Northeast Ontario".Journal of Petrology.18(2): 319–369.doi:10.1093/petrology/18.2.319.

- ^Gill, Robin (2010).Igneous rocks and processes: a practical guide.Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.ISBN978-1-4443-3065-6.

- ^Emeleus, C. H.; Troll, V. R. (August 2014)."The Rum Igneous Centre, Scotland".Mineralogical Magazine.78(4): 805–839.Bibcode:2014MinM...78..805E.doi:10.1180/minmag.2014.078.4.04.ISSN0026-461X.

- ^Philpotts & Ague 2009,p. 102.

- ^Philpotts & Ague 2009,pp. 370–374.

- ^Philpotts & Ague 2009,pp. 95–99.

- ^Philpotts & Ague 2009,p. 99.

- ^Iwasaki, I.; Malicsi, A.S.; Lipp, R.J.; Walker, J.S. (August 1982). "By-product recovery from copper-nickel bearing duluth gabbro".Resources and Conservation.9:105–117.doi:10.1016/0166-3097(82)90066-9.

- ^Lachize, M.; Lorand, J. P.; Juteau, T. (1991). "Cu-Ni-PGE Magmatic Sulfide Ores and their Host Layered Gabbros in the Haymiliyah Fossil Magma Chamber (Haylayn Block, Semail Ophiolite Nappe, Oman)".Ophiolite Genesis and Evolution of the Oceanic Lithosphere.Petrology and Structural Geology. Vol. 5. pp. 209–229.doi:10.1007/978-94-011-3358-6_12.ISBN978-94-010-5484-3.

- ^Arnason, John G.; Bird, Dennis K. (August 2000). "A Gold- and Platinum-Mineralized Layer in Gabbros of The Kap Edvard Holm Complex: Field, Petrologic, and Geochemical Relations".Economic Geology.95(5): 945–970.doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.95.5.945.

- ^Philpotts & Ague 2009,pp. 384–390.

- ^Winkler, Erhard M. (1994).Stone in architecture: properties, durability(3rd completely rev. and extended ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 101.ISBN9783540576266.

- ^National Research Council (1 January 1982).Conservation of Historic Stone Buildings and Monuments.p. 80.doi:10.17226/514.ISBN978-0-309-03275-9.