Galactose

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Galactose

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2S,3R,4S,5R,6R)-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-2,3,4,5-tetrol | |||

| Other names

Brain sugar

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1724619 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Galactose | ||

PubChemCID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12O6 | |||

| Molar mass | 180.156g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White solid[1] | ||

| Odor | Odorless[1] | ||

| Density | 1.5 g/cm3[1] | ||

| Melting point | 168–170 °C (334–338 °F; 441–443 K)[1] | ||

| 650 g/L (20 °C)[1] | |||

| -103.00·10−6cm3/mol | |||

| Pharmacology | |||

| V04CE01(WHO)V08DA02(WHO) (microparticles) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704(fire diamond) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in theirstandard state(at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Galactose(/ɡəˈlæktoʊs/,galacto-+-ose,"milk sugar" ), sometimes abbreviatedGal,is amonosaccharidesugar that is about assweetasglucose,and about 65% as sweet assucrose.[2]It is analdohexoseand a C-4epimerof glucose.[3]A galactose molecule linked with a glucose molecule forms alactosemolecule.

Galactanis apolymericform of galactose found inhemicellulose,and forming the core of the galactans, a class of natural polymeric carbohydrates.[4]

D-Galactose is also known as brain sugar since it is a component ofglycoproteins(oligosaccharide-protein compounds) found innervetissue.[5]

Etymology[edit]

The wordgalactosewas coined by Charles Weissman[6]in the mid-19th century and is derived from Greekγαλακτος,galaktos,(of milk) and the generic chemical suffix for sugars-ose.[7]The etymology is comparable to that of the wordlactosein that both contain roots meaning "milk sugar". Lactose is adisaccharideof galactose plusglucose.

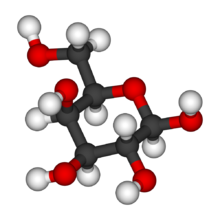

Structure and isomerism[edit]

Galactose exists in both open-chain and cyclic form. The open-chain form has acarbonylat the end of the chain.

Four isomers are cyclic, two of them with apyranose(six-membered) ring, two with afuranose(five-membered) ring. Galactofuranose occurs in bacteria, fungi and protozoa,[8][9]and is recognized by a putative chordate immune lectinintelectinthrough its exocyclic 1,2-diol. In the cyclic form there are twoanomers,named alpha and beta, since the transition from the open-chain form to the cyclic form involves the creation of a newstereocenterat the site of the open-chain carbonyl.[10]

TheIR spectrafor galactose shows a broad, strong stretch from roughly wavenumber 2500 cm−1to wavenumber 3700 cm−1.[11]

TheProton NMRspectra for galactose includes peaks at 4.7 ppm (D2O), 4.15 ppm (−CH2OH), 3.75, 3.61, 3.48 and 3.20 ppm (−CH2of ring), 2.79–1.90 ppm (−OH).[11]

Relationship to lactose[edit]

Galactose is amonosaccharide.When combined with glucose (another monosaccharide) through acondensation reaction,the result is a disaccharide called lactose. Thehydrolysisof lactose to glucose and galactose iscatalyzedby theenzymeslactaseandβ-galactosidase.The latter is produced by thelacoperoninEscherichia coli.[12]

In nature, lactose is found primarily in milk and milk products. Consequently, various food products made with dairy-derived ingredients can contain lactose.[13]Galactosemetabolism,which converts galactose into glucose, is carried out by the three principal enzymes in a mechanism known as theLeloir pathway.The enzymes are listed in the order of the metabolic pathway: galactokinase (GALK), galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT), and UDP-galactose-4’-epimerase (GALE).[citation needed]

In humanlactation,galactose is required in a 1 to 1 ratio with glucose to enable themammary glandsto synthesize and secrete lactose. In a study where women were fed a diet containing galactose, 69 ± 6% of glucose and 54 ± 4% of galactose in the lactose they produced were derived directly from plasma glucose, while 7 ± 2% of the glucose and 12 ± 2% of the galactose in the lactose, were derived directly from plasma galactose. 25 ± 8% of the glucose and 35 ± 6% of the galactose was synthesized from smaller molecules such as glycerol or acetate in a process referred to in the paper as hexoneogenesis. This suggests that the synthesis of galactose is supplemented by direct uptake and of use of plasma galactose when present.[14]

Metabolism[edit]

| Metabolism of commonmonosaccharidesand some biochemical reactions of glucose |

|---|

|

Glucose is more stable than galactose and is less susceptible to the formation of nonspecific glycoconjugates, molecules with at least one sugar attached to a protein or lipid. Many speculate that it is for this reason that a pathway for rapid conversion from galactose to glucose has beenhighly conservedamong many species.[15]

The main pathway of galactose metabolism is theLeloir pathway;humans and other species, however, have been noted to contain several alternate pathways, such as theDe Ley Doudoroff Pathway.The Leloir pathway consists of the latter stage of a two-part process that converts β-D-galactose toUDP-glucose.The initial stage is the conversion of β-D-galactose to α-D-galactose by the enzyme, mutarotase (GALM). The Leloir pathway then carries out the conversion of α-D-galactose to UDP-glucose via three principal enzymes: Galactokinase (GALK) phosphorylates α-D-galactose to galactose-1-phosphate, or Gal-1-P; Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT) transfers a UMP group from UDP-glucose to Gal-1-P to form UDP-galactose; and finally, UDP galactose-4’-epimerase (GALE) interconverts UDP-galactose and UDP-glucose, thereby completing the pathway.[16]

The above mechanisms for galactose metabolism are necessary because the human body cannot directly convert galactose into energy, and must first go through one of these processes in order to utilize the sugar.[17]

Galactosemiais an inability to properly break down galactose due to a genetically inherited mutation in one of the enzymes in the Leloir pathway. As a result, the consumption of even small quantities is harmful to galactosemics.[18]

Sources[edit]

Galactose is found indairy products,avocados,sugar beets,othergumsandmucilages.It is alsosynthesizedby the body, where it forms part ofglycolipidsandglycoproteinsin severaltissues;and is a by-product from thethird-generation ethanolproduction process (from macroalgae).[citation needed]

Clinical significance[edit]

Chronic systemic exposure ofmice,rats,andDrosophilato D-galactose causes the acceleration ofsenescence(aging). It has been reported that high dose exposure of D-galactose (120 mg/kg) can cause reduced sperm concentration and sperm motility in rodents and has been extensively used as an aging model when administered subcutaneously.[19][20][21] Two studies have suggested a possible link between galactose in milk andovarian cancer.[22][23]Other studies show no correlation, even in the presence of defective galactose metabolism.[24][25]More recently, pooled analysis done by theHarvard School of Public Healthshowed no specific correlation between lactose-containing foods and ovarian cancer, and showed statistically insignificant increases in risk for consumption of lactose at 30 g/day.[26]More research is necessary to ascertain possible risks.[citation needed]

Some ongoing studies suggest galactose may have a role in treatment offocal segmental glomerulosclerosis(a kidney disease resulting in kidney failure and proteinuria).[27]This effect is likely to be a result of binding of galactose to FSGS factor.[28]

Galactose is a component of theantigens(chemical markers) present on blood cells that distinguish blood type within theABO blood group system.In O and A antigens, there are twomonomersof galactose on the antigens, whereas in the B antigens there are three monomers of galactose.[29]

A disaccharide composed of two units of galactose,galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose(alpha-gal), has been recognized as a potentialallergenpresent inmammal meat.Alpha-gal allergymay be triggered bylone star tickbites.[30]

Galactose in sodium saccharin solution has also been found to cause conditioned flavor avoidance in adult female rats within a laboratory setting when combined with intragastric injections.[31]The reason for this flavor avoidance is still unknown, however it is possible that a decrease in the levels of the enzymes required to convert galactose to glucose in the liver of the rats could be responsible.[31]

History[edit]

In 1855, E. O. Erdmann noted that hydrolysis of lactose produced a substance besides glucose.[32][33]

Galactose was first isolated and studied byLouis Pasteurin 1856 and he called it "lactose".[34]In 1860,Berthelotrenamed it "galactose" or "glucose lactique".[35][36]In 1894,Emil Fischerand Robert Morrell determined theconfigurationof galactose.[37]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^abcdeRecordin theGESTIS Substance Databaseof theInstitute for Occupational Safety and Health

- ^Spillane WJ (2006-07-17).Optimising Sweet Taste in Foods.Woodhead Publishing. p. 264.ISBN9781845691646.

- ^Kalsi PS (2007).Organic Reactions Stereochemistry And Mechanism (Through Solved Problems).New Age International. p. 43.ISBN9788122417661.

- ^Zanetti M, Capra DJ (2003-09-02).The Antibodies.CRC Press. p. 78.ISBN9780203216514.

- ^"16.3 Important Hexoses | The Basics of General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry".courses.lumenlearning.com.Retrieved2022-05-06.

- ^"Charles Weismann in the 1940 Census".Ancestry.Retrieved26 December2017.

- ^Bhat PJ (2 March 2008).Galactose Regulon of Yeast: From Genetics to Systems Biology.Springer Science & Business Media.ISBN9783540740155.Retrieved26 December2017.

- ^Nassau PM, Martin SL, Brown RE, Weston A, Monsey D, McNeil MR, et al. (February 1996)."Galactofuranose biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12: identification and cloning of UDP-galactopyranose mutase".Journal of Bacteriology.178(4): 1047–52.doi:10.1128/jb.178.4.1047-1052.1996.PMC177764.PMID8576037.

- ^Tefsen B, Ram AF, van Die I, Routier FH (April 2012)."Galactofuranose in eukaryotes: aspects of biosynthesis and functional impact".Glycobiology.22(4): 456–69.doi:10.1093/glycob/cwr144.PMID21940757.

- ^"Ophardt, C. Galactose".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-09-08.Retrieved2015-11-26.

- ^abTunki, Lakshmi; Kulhari, Hitesh; Vadithe, Lakshma Nayak; Kuncha, Madhusudana; Bhargava, Suresh; Pooja, Deep; Sistla, Ramakrishna (2019-09-01)."Modulating the site-specific oral delivery of sorafenib using sugar-grafted nanoparticles for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment".European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences.137:104978.doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2019.104978.ISSN0928-0987.PMID31254645.S2CID195764874.

- ^Sanganeria, Tanisha; Bordoni, Bruno (2023),"Genetics, Inducible Operon",StatPearls,Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing,PMID33232031,retrieved2023-10-24

- ^Staff (June 2009)."Lactose Intolerance – National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse".digestive.niddk.nih.gov.Archived fromthe originalon November 25, 2011.RetrievedJanuary 11,2014.

- ^Sunehag A, Tigas S, Haymond MW (January 2003)."Contribution of plasma galactose and glucose to milk lactose synthesis during galactose ingestion".The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.88(1): 225–9.doi:10.1210/jc.2002-020768.PMID12519857.

- ^Fridovich-Keil JL, Walter JH."Galactosemia".In Valle D, Beaudet AL, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Antonarakis SE, Ballabio A, Gibson KM, Mitchell G (eds.).The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease.Archived fromthe originalon 2018-06-26.Retrieved2018-06-25.

a 4 b 21 c 22 d 22 - ^Bosch AM (August 2006). "Classical galactosaemia revisited".Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease.29(4): 516–25.doi:10.1007/s10545-006-0382-0.PMID16838075.S2CID16382462.

a 517 b 516 c 519 - ^Berg, Jeremy M.; Tymoczko, John L.; Stryer, Lubert (2013).Stryer Biochemie.doi:10.1007/978-3-8274-2989-6.ISBN978-3-8274-2988-9.

- ^Berry GT (1993)."Classic Galactosemia and Clinical Variant Galactosemia".Nih.gov.University of Washington, Seattle.PMID20301691.Retrieved17 May2015.

- ^Pourmemar E, Majdi A, Haramshahi M, Talebi M, Karimi P, Sadigh-Eteghad S (January 2017). "Intranasal Cerebrolysin Attenuates Learning and Memory Impairments in D-galactose-Induced Senescence in Mice".Experimental Gerontology.87(Pt A): 16–22.doi:10.1016/j.exger.2016.11.011.PMID27894939.S2CID40793896.

- ^Cui X, Zuo P, Zhang Q, Li X, Hu Y, Long J, Packer L, Liu J (August 2006). "Chronic systemic D-galactose exposure induces memory loss, neurodegeneration, and oxidative damage in mice: protective effects of R-alpha-lipoic acid".Journal of Neuroscience Research.84(3): 647–54.doi:10.1002/jnr.20899.PMID16710848.S2CID13641006.

- ^Zhou YY, Ji XF, Fu JP, Zhu XJ, Li RH, Mu CK, et al. (2015-07-15)."Gene Transcriptional and Metabolic Profile Changes in Mimetic Aging Mice Induced by D-Galactose".PLOS ONE.10(7): e0132088.Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1032088Z.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132088.PMC4503422.PMID26176541.

- ^Cramer DW (November 1989). "Lactase persistence and milk consumption as determinants of ovarian cancer risk".American Journal of Epidemiology.130(5): 904–10.doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115423.PMID2510499.

- ^Cramer DW, Harlow BL, Willett WC, Welch WR, Bell DA, Scully RE, Ng WG, Knapp RC (July 1989). "Galactose consumption and metabolism in relation to the risk of ovarian cancer".Lancet.2(8654): 66–71.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90313-9.PMID2567871.S2CID34304536.

- ^Goodman MT, Wu AH, Tung KH, McDuffie K, Cramer DW, Wilkens LR, et al. (October 2002)."Association of galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase activity and N314D genotype with the risk of ovarian cancer".American Journal of Epidemiology.156(8): 693–701.doi:10.1093/aje/kwf104.PMID12370157.

- ^Fung WL, Risch H, McLaughlin J, Rosen B, Cole D, Vesprini D, Narod SA (July 2003). "The N314D polymorphism of galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase does not modify the risk of ovarian cancer".Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.12(7): 678–80.PMID12869412.

- ^Genkinger JM, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Anderson KE, Arslan A, Beeson WL, et al. (February 2006). "Dairy products and ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of 12 cohort studies".Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.15(2): 364–72.doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0484.PMID16492930.

- ^De Smet E, Rioux JP, Ammann H, Déziel C, Quérin S (September 2009)."FSGS permeability factor-associated nephrotic syndrome: remission after oral galactose therapy".Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation.24(9): 2938–40.doi:10.1093/ndt/gfp278.PMID19509024.

- ^McCarthy ET, Sharma M, Savin VJ (November 2010)."Circulating permeability factors in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis".Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.5(11): 2115–21.doi:10.2215/CJN.03800609.PMID20966123.

- ^Raven PH, Johnson GB (1995). Mills CJ (ed.).Understanding Biology(3rd ed.). WM C. Brown. p. 203.ISBN978-0-697-22213-8.

- ^"Alpha-gal syndrome - Symptoms and causes".Mayo Clinic.Retrieved2022-02-25.

- ^abSclafani, Anthony; Fanizza, Lawrence J; Azzara, Anthony V (1999-08-15)."Conditioned Flavor Avoidance, Preference, and Indifference Produced by Intragastric Infusions of Galactose, Glucose, and Fructose in Rats".Physiology & Behavior.67(2): 227–234.doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00053-0.ISSN0031-9384.PMID10477054.S2CID37225025.

- ^Erdmann EO (1855).Dissertatio de saccharo lactico et amylaceo[Dissertation on milk sugar and starch] (Thesis) (in Latin). University of Berlin.

- ^"Jahresbericht über die Fortschritte der reinen, pharmaceutischen und technischen Chemie"[Annual report on progress in pure, pharmaceutical, and technical chemistry] (in German). 1855. pp. 671–673.see especially p. 673.

- ^Pasteur L (1856)."Note sur le sucre de lait"[Note on milk sugar].Comptes rendus(in French).42:347–351.

From page 348: Je propose de le nommerlactose.(I propose to name itlactose.)

- ^Berthelot M (1860)."Chimie organique fondée sur la synthèse"[Organic chemistry based on synthesis].Mallet-Bachelier(in French).2.Paris, France: 248–249.

- ^"Galactose" — from theAncient Greekγάλακτος(gálaktos, “milk” ).

- ^Fischer E, Morrell RS (1894)."Ueber die Configuration der Rhamnose und Galactose"[On the configuration of rhamnose and galactose].Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin(in German).27:382–394.doi:10.1002/cber.18940270177.The configuration of galactose appears on page 385.

External links[edit]

Media related toGalactoseat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toGalactoseat Wikimedia Commons