Gastric antral vascular ectasia

| Gastric antral vascular ectasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Watermelon stomach, watermelon disease |

| |

| Endoscopicimage of gastric antral vascular ectasia seen as a radial pattern around thepylorusbefore (top) and after (bottom) treatment withargon plasma coagulation | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Bleedingin the stomach and intestines,edema,dilated blood vessels |

Gastric antral vascular ectasia(GAVE) is an uncommon cause of chronicgastrointestinal bleedingoriron deficiency anemia.[1][2]The condition is associated with dilated small blood vessels in thegastric antrum,which is a distal part of thestomach.[1]The dilated vessels result in intestinal bleeding.[3]It is also calledwatermelon stomachbecause streaky long red areas that are present in the stomach may resemble the markings onwatermelon.[1][2][3][4]

The condition was first discovered in 1952,[2]and reported in the literature in 1953.[5]Watermelon disease was first diagnosed by Wheeleret al.in 1979, and definitively described in four living patients by Jabbariet al.only in 1984.[4]As of 2011, the cause and pathogenesis are still not known.[4][6]However, there are several competing hypotheses as to various causes.[4]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Most patients who are eventually diagnosed with watermelon stomach come to a physician complaining ofanemiaand blood loss.[7]Sometimes, a patient may come to thephysicianbecause he or she notices blood in the stools—eithermelena(black and tarry stools) and/orhematochezia(red bloody stools).[7]

Cause[edit]

The literature, from 1953 through 2010, often cited that the cause of gastric antral vascular ectasia is unknown.[4][6][7]The causal connection betweencirrhosisand GAVE has not been proven.[6]Aconnective tissuedisease has been suspected in some cases.[7]

Autoimmunity may have something to do with it,[8]as 25% of all sclerosis patients who had a certain anti-RNA marker have GAVE.[9]RNA autoimmunity has been suspected as a cause or marker since at least 1996.[8]Gastrinlevels may indicate a hormonal connection.[6]

Associated conditions[edit]

GAVE is associated with a number of conditions, includingportal hypertension,chronic kidney failure,andcollagen vascular diseases.[2][10][11]

Watermelon stomach also occurs particularly withscleroderma,[2][12][13][14]and especially the subtype known as systemic sclerosis.[2][9]A full 5.7% of persons with sclerosis have GAVE, and 25% of all sclerosis patients who had a certain anti-RNA polymerase marker have GAVE.[9]In fact:

Most patients with GAVE suffer from liver cirrhosis, autoimmune disease, chronic kidney failure and bone marrow transplantation. The typical initial presentations range from occult bleeding causing transfusion-dependent chronic iron-deficiency anemia to severe acute gastrointestinal bleeding.

— Masae Komiyama,et al.,2010.[10]

The endoscopic appearance of GAVE is similar toportal hypertensive gastropathy,but is not the same condition, and may be concurrent withcirrhosis of the liver.[2][6][15][16]30% of all patients have cirrhosis associated with GAVE.[6]

Sjögren's syndromehas been associated with at least one patient.[17]

The first case ofectopic pancreasassociated with watermelon stomach was reported in 2010.[4]

Patients with GAVE may have elevatedgastrinlevels.[6]

The Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) states thatpernicious anemiais one of the conditions associated with GAVE,[18]and one separate study showed that over three-fourths of the patients in the study with GAVE had some kind ofvitamin B12deficiencyincluding the associated condition pernicious anemia.[19]

Intestinal permeabilityanddiverticulitismay occur in some patients with GAVE.

Pathogenesis[edit]

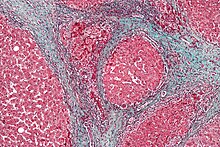

GAVE is characterized by dilated capillaries in thelamina propriawithfibrinthrombi.The mainhistomorphologicdifferential diagnosis isportal hypertension,which is often apparent from clinical findings.[citation needed]

Research in 2010 has shown that anti-RNA polymeraseIII antibodies may be used as arisk markerfor GAVE insystemic sclerosispatients.[9]

Diagnosis[edit]

GAVE is usually diagnosed definitively by means of anendoscopicbiopsy.[6][7][10][20]The tell-tale watermelon stripes show up during the endoscopy.[7]

Surgical exploration of theabdomenmay be needed to diagnose some cases, especially if the liver or other organs are involved.[4]

Differential diagnosis[edit]

GAVE results in intestinal bleeding similar toduodenal ulcersandportal hypertension.[3][6]The GI bleeding can result inanemia.[6][7]It is often overlooked, but can be more common in elderly patients.[3][7]It has been seen in a female patient of 26 years of age.[6]

Watermelon stomach has a different etiology and has adifferential diagnosisfrom portal hypertension.[6][15]In fact, cirrhosis and portal hypertension may be missing in a patient with GAVE.[6]The differential diagnosis is important because treatments are different.[3][6][7][10]

Treatment[edit]

Traditional treatments[edit]

GAVE is treated commonly by means of an endoscope, includingargon plasma coagulationand electrocautery.[6][7][21]Since endoscopy with argon photocoagulation is "usually effective", surgery is "usually not required".[7]Coagulation therapy is well tolerated but "tends to induce oozing and bleeding."[7]"Endoscopy with thermal ablation" is favoredmedical treatmentbecause of its low side effects and low mortality, but is "rarely curative."[6]Treatment of GAVE can be categorized into endoscopic, surgical and pharmacologic. Surgical treatment is definitive but it is rarely done nowadays with the variety of treatment options available. Some of the discussed modalities have been used in GAVE patients with another underlying disease rather than SSc; they are included as they may be tried in resistant SSc-GAVE patients. Symptomatic treatment includes iron supplementation and blood transfusion for cases with severe anemia, proton pump inhibitors may ameliorate the background chronic gastritis and minute erosions that commonly co-existed in biopsy reports.[11]

Medications[edit]

Other medical treatments have been tried and includeestrogenandprogesteronetherapy,[21]Corticostreoids are effective, but are "limited by theirside effects."[7]

Treatment of co-morbid conditions[edit]

Atransjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt(TIPS or TIPSS) procedure is used to treat portal hypertension when that is present as an associated condition. Unfortunately, the TIPSS, which has been used for similar conditions, may cause or exacerbatehepatic encephalopathy.[22][23]TIPSS-related encephalopathy occurs in about 30% of cases, with the risk being higher in those with previous episodes of encephalopathy, higher age, female sex, and liver disease due to causes other than alcohol.[24]The patient, with their physician and family, must balance out a reduction in bleeding caused by TIPS with the significant risk ofencephalopathy.[22][23][24]Various shunts have been shown in ameta-studyof 22 studies to be effective treatment to reduce variceal bleeding, yet none have any demonstrated survival advantage.[22]

If there is cirrhosis of the liver that has progressed toliver failure,thenlactulosemay be prescribed for hepatic encephalopathy, especially forType C encephalopathywithdiabetes.[24]Also, "antibiotics such asneomycin,metronidazole,andrifaximin"may be used effectively to treat the encephalopathy by removing nitrogen-producing bacteria from the gut.[24]

Paracentesis,a medical procedure involving needle drainage of fluid from abody cavity,[25]may be used to remove fluid from theperitoneal cavityin theabdomenfor such cases.[23]This procedure uses a large needle, similar to the better-knownamniocentesis.

Surgery[edit]

Surgery, consisting of excision of part of the lower stomach, also calledantrectomy,is another option.[6][16]Antrectomy is "the resection, or surgical removal, of a part of the stomach known as theantrum".[2]Laparoscopic surgeryis possible in some cases, and as of 2003, was a "novel approach to treating watermelon stomach".[26]

A treatment used sometimes is endoscopic band ligation.[27]

In 2010, a team ofJapanesesurgeons performed a "novel endoscopicablationof gastric antral vascular ectasia ".[10]The experimental procedure resulted in "no complications".[10]

Relapse is possible, even after treatment by argon plasma coagulation and progesterone.[21]

Antrectomy or othersurgeryis used as a last resort for GAVE.[2][6][7][10][15][16][excessive citations]

Epidemiology[edit]

The average age of diagnosis for GAVE is 73 years of age for females,[3][7]and 68 for males.[2]Women are about twice as often diagnosed with gastric antral vascular ectasia than men.[2][7]71% of all cases of GAVE are diagnosed in females.[3][7]Patients in their thirties have been found to have GAVE.[6]It becomes more common in women in their eighties, rising to 4% of all such gastrointestinal conditions.[10]

5.7% of all sclerosis patients (and 25% of those who had a certain anti-RNA marker) have GAVE.[9]

References[edit]

- ^abcSuit, PF; Petras, RE; Bauer, TW; Petrini Jr, JL (1987). "Gastric antral vascular ectasia. A histologic and morphometric study of" the watermelon stomach "".The American Journal of Surgical Pathology.11(10): 750–7.doi:10.1097/00000478-198710000-00002.PMID3499091.S2CID36333766.

- ^abcdefghijkSurgery Encyclopedia website page on Antrectomy.Accessed September 29, 2010.

- ^abcdefgNguyen, Hien; Le, Connie; Nguyen, Hanh (2009)."Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach)-an enigmatic and often-overlooked cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly".The Permanente Journal.13(4): 46–9.doi:10.7812/TPP/09-055.PMC2911825.PMID20740102.

- ^abcdefgYildiz, Baris; Sokmensuer, Cenk; Kaynaroglu, Volkan (2010)."Chronic anemia due to watermelon stomach".Annals of Saudi Medicine.30(2): 156–8.doi:10.4103/0256-4947.60524.PMC2855069.PMID20220268.

- ^Rider, JA; Klotz, AP; Kirsner, JB (1953). "Gastritis with veno-capillary ectasia as a source of massive gastric hemorrhage".Gastroenterology.24(1): 118–23.doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(53)80070-3.PMID13052170.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrsTuveri, Massimiliano; Borsezio, Valentina; Gabbas, Antonio; Mura, Guendalina (2007). "Gastric antral vascular ectasia—an unusual cause of gastric outlet obstruction: report of a case".Surgery Today.37(6): 503–5.doi:10.1007/s00595-006-3430-3.PMID17522771.S2CID25727751.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqRosenfeld, G; Enns, R (2009)."Argon photocoagulation in the treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia and radiation proctitis".Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology.23(12): 801–4.doi:10.1155/2009/374138.PMC2805515.PMID20011731.

- ^abValdez, BC; Henning, D; Busch, RK; Woods, K; Flores-Rozas, H; Hurwitz, J; Perlaky, L; Busch, H (1996)."A nucleolar RNA helicase recognized by autoimmune antibodies from a patient with watermelon stomach disease".Nucleic Acids Research.24(7): 1220–4.doi:10.1093/nar/24.7.1220.PMC145780.PMID8614622.

- ^abcdeCeribelli, A; Cavazzana, I; Airò, P; Franceschini, F (2010)."Anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies as a risk marker for early gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) in systemic sclerosis"(PDF).The Journal of Rheumatology.37(7): 1544.doi:10.3899/jrheum.100124.PMID20595295.

- ^abcdefghKomiyama, Masae; Fu, K; Morimoto, T; Konuma, H; Yamagata, T; Izumi, Y; Miyazaki, A; Watanabe, S (2010)."A novel endoscopic ablation of gastric antral vascular ectasia".World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.2(8): 298–300.doi:10.4253/wjge.v2.i8.298.PMC2999147.PMID21160630.

- ^abEl-Gendy, Hala; Shohdy, Kyrillus S.; Maghraby, Gehad G.; Abadeer, Kerolos; Mahmoud, Moustafa (2017-02-01). "Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis: Where do we stand?".International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases.20(12): 2133–2139.doi:10.1111/1756-185X.13047.ISSN1756-185X.PMID28217887.S2CID24009655.

- ^Scleroderma Association websiteArchived2015-05-07 at theWayback Machine.Accessed September 29, 2010.

- ^Marie, I.; Ducrotte, P.; Antonietti, M.; Herve, S.; Levesque, H. (2008). "Watermelon stomach in systemic sclerosis: its incidence and management".Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.28(4): 412–421.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03739.x.PMID18498445.S2CID205244678.

- ^Ingraham, KM; O'Brien, MS; Shenin, M; Derk, CT; Steen, VD (2010)."Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis: demographics and disease predictors".The Journal of Rheumatology.37(3): 603–7.doi:10.3899/jrheum.090600.PMID20080908.S2CID207603440.

- ^abcSpahr, L; Villeneuve, J-P; Dufresne, M-P; Tasse, D; Bui, B; Willems, B; Fenyves, D; Pomier-Layrargues, G (1999)."Gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhotic patients: absence of relation with portal hypertension".Gut.44(5): 739–42.doi:10.1136/gut.44.5.739.PMC1727493.PMID10205216.

- ^abcSpahr, L; Villeneuve, JP; Dufresne, MP; Tassé, D; Bui, B; Willems, B; Fenyves, D; Pomier-Layrargues, G (1999)."Gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhotic patients: absence of relation with portal hypertension".Gut.44(5): 739–42.doi:10.1136/gut.44.5.739.PMC1727493.PMID10205216.

- ^Krstić, M; Alempijević, T; Andrejević, S; Zlatanović, M; Damjanov, N; Ivanović, B; Jovanović, I; Tarabar, D; Milosavljević, T (2010)."Watermelon stomach in a patient with primary Sjögren's syndrome".Vojnosanitetski Pregled. Military-medical and Pharmaceutical Review.67(3): 256–8.doi:10.2298/VSP1003256K.PMID20361704.

- ^"Watermelon Stomach"Archived2012-01-01 at theWayback MachineGenetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD),National Institution of Health.

- ^"Watermelon Stomach and Radiiation ProctopathyCCS Publishing,August 1, 2011

- ^Gilliam, John H.; Geisinger, Kim R.; Wu, Wallace C.; Weidner, Noel; Richter, Joel E. (1989). "Endoscopic biopsy is diagnostic in gastric antral vascular ectasia".Digestive Diseases and Sciences.34(6): 885–8.doi:10.1007/BF01540274.PMID2721320.S2CID25328326.

- ^abcShibukawa, G; Irisawa, A; Sakamoto, N; Takagi, T; Wakatsuki, T; Imamura, H; Takahashi, Y; Sato, A; et al. (2007)."Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) associated with systemic sclerosis: relapse after endoscopic treatment by argon plasma coagulation".Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan).46(6): 279–83.doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6203.PMID17379994.

- ^abcKhan S, Tudur Smith C, Williamson P, Sutton R (2006). "Portosystemic shunts versus endoscopic therapy for variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2006(4): CD000553.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000553.pub2.PMC7045742.PMID17054131.

- ^abcSaab S, Nieto JM, Lewis SK, Runyon BA (2006). "TIPS versus paracentesis for cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2010(4): CD004889.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004889.pub2.PMC8855742.PMID17054221.

- ^abcdSundaram V, Shaikh OS (July 2009). "Hepatic encephalopathy: pathophysiology and emerging therapies".Med. Clin. North Am.93(4): 819–36, vii.doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2009.03.009.PMID19577116.

- ^"paracentesis"atDorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^Sherman, V; Klassen, DR; Feldman, LS; Jabbari, M; Marcus, V; Fried, GM (2003). "Laparoscopic antrectomy: a novel approach to treating watermelon stomach".Journal of the American College of Surgeons.197(5): 864–7.doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00600-8.PMID14585429.

- ^Wells, C; Harrison, M; Gurudu, S; Crowell, M; Byrne, T; Depetris, G; Sharma, V (2008). "Treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) with endoscopic band ligation".Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.68(2): 231–6.doi:10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.021.PMID18533150.

Further reading[edit]

- Thonhofer, R; Siegel, C; Trummer, M; Gugl, A (2010). "Clinical images: Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis".Arthritis and Rheumatism.62(1): 290.doi:10.1002/art.27185.PMID20039398.