Kim Jeong-hui

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(March 2024) |

| Kim Jeong-hui | |

| |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 김정희 |

| Hanja | Kim chính hỉ |

| Revised Romanization | Gim Jeonghui |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kim Chŏnghŭi |

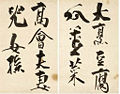

Kim Jeong-hui(Korean:김정희,Korean pronunciation:[kimdʑʌŋçi];1786–1856) was one of the most celebrated practitioners ofcalligraphy,epigraphists, and scholars ofKorea's laterJoseonperiod.[1]He was a member of theGyeongju Kim clan.He used variousart names:Wandang ( nguyễn đường ), Chusa ( thu sử ), Yedang ( lễ đường ), Siam ( thi am ), Gwapa ( quả pha ), Nogwa ( lão quả ) etc. (up to 503 by some estimates[2]). He is especially celebrated for having transformed Korean epigraphy and for having created the "Chusa-che" (Thu sử thể;lit.Chusa writing style) inspired by his study of ancient Korean and Chinese epitaphs. His ink paintings, especially of orchids, are equally admired.

As a scholar, he belonged to theSilhak(Practical Learning) school also known as the Bukhak ( bắc học, "Northern Learning" ). He was related to QueenJeongsun,the second wife of KingYeongjo,and by his adoptive mother, Nam Yang-hong, he was a cousin to Namyeon-gun Yi Gu, who was destined to be the grandfather of KingGojong( cao tông, later titled quang võ đế Gwangmu Emperor. 1852–1919).Heungseon Daewongun( hưng tuyên đại viện quân, 1820–1898), KingGojong's father who served as his regent and was also a noted calligrapher, was one of Kim's pupils for a while.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Kim was born in the family home inYesan,nowSouth Chungcheong Province,in 1786. He was the eldest son. His birth father was Kim No-gyeong ( kim lỗ kính, 1766–1840); his grandfather was Kim I-ju ( kim di trụ, 1730–1797) and his great-grandfather was Weolseongui Kim Han-sin ( nguyệt thành úy kim hán tẫn, 1720–1758) who married the second daughter of KingYeongjo,the Princess Hwasun ( hòa thuận ông chủ, 1720–1758). His ancestors and relatives held many high administrative positions and several were noted for their calligraphy. His mother was a member of the Gigye Yu clan, a daughter of Yu Jun-ju ( du tuấn trụ ), the governor ofGimhae.

He is reputed to have been a remarkable calligrapher already as a child. When he was 7, the famed scholar Chae Je-gong ( thái tế cung, 1720–1799) is said to have been impressed on seeing the "Ipchun Daegil Cheonha Daepyeongchun" ( lập xuân đại cát thiên hạ thái bình xuân ) good-luck charm marking the coming of spring that he had written, pasted on the gate of the family home.[3]From the age of 15 he received instruction from the celebrated Bukhak ( bắc học, "Northern Learning" ) scholarPak Je-ga( phác tề gia, 1750–1805).

Early youth

[edit]In the 1790s, the head of the family, his eldest uncle, Kim No-yeong ( kim lỗ vĩnh, 1747–1707), was sent into exile, while another uncle as well as his grandparents all died in quick succession. It was decided that Kim Jeong-hui should be adopted by Kim No-yeong (who had several daughters but no son) and so become the next head of the family. When he was 15, in 1800, he married a member of the Hansan Yi clan ( nhàn sơn lý thị ). That same year, KingJeongjodied and QueenJeongsun,the widow of the previousKing Yeongjo,became regent, since the new king was only a child. Kim Jeong-hui's birth father benefitted from the family's relationship with the regent and was raised to a high rank.

Later youth

[edit]Kim Jeong-hui's birth mother died in 1801, aged only 34. QueenJeongsundied in 1805, and Kim Jeong-hui's young wife died only a few weeks after her. His teacherPak Je-gaalso died that year and these multiple deaths seem to have encouraged his already deep interest inBuddhismas a source of consolation and meaning. His adoptive mother also died at around this time and once mourning for her was over, he married a slightly younger second wife in 1808, a member of the Yean Yi clan ( lễ an lý thị ). In 1809 he took first place in the lowerGwageocivil examination.

Adult life

[edit]Visit to China

[edit]In 1810, his birth-father was appointed a vice-envoy in the annual embassy toQingChinaand he accompanied him, spending some 6 months in China. There he met such noted scholars asWeng Fanggang( ông phương cương, 1733–1818) andRuan Yuan( nguyễn nguyên, 1764–1849) who recognized his qualities. He seems to have studied documentary history there especially. Ruan Yuan gave him a copy of his "Su Zhai Biji" ( tô trai bút ký ), a book aboutcalligraphy,and Kim continued to correspond with them after his return to Korea. For a time after returning home he did not take up any official position but continued to study the Northern Learning and write essays criticizing rigidNeo-Confucianism.

He also pursued research by visiting and studying the inscriptions on ancient stele. In 1815, the VenerableCho-uifirst visited Seoul and met Kim Jeong-hui there. This was the beginning of a deep and lasting relationship. Perhaps it was from this time that Kim began to drink tea, there is no knowing.

Success in national exams

[edit]Passing theGwageonational exam held to mark an eclipse year in 1819, he rose to such positions as secret inspector and tutor to the Crown Prince. Following the death of the prince, power passed to the conservative Andong Kim clan and Kim was reduced in rank while his adoptive father was exiled for several years, until 1834. In 1835, after the accession of KingHeonjong,the family's fortunes turned and Kim Jeong-hui rose to ministerial rank. In the same year he visited the Ven.Cho-uiat Daedun-sa temple ( đại 芚 tự ), now called Daeheung-sa).

Exile

[edit]Following the death of KingSunjo of Joseon(r. 1800–1834) late in 1834,Queen Sunwon,the wife of Sunjo and a member of the Kim clan of Andong, held immense power after her grandson,Heonjong( hiến tông, 1827–1849 ), still only a child, was made king. Queen Kim acted as his regent. Factional in-fighting increased and in 1840, when he was due to be a member of the Chinese embassy, Kim Jeong-hui was instead condemned to exile inJeju Island.Late in 1842, his wife died. He was finally allowed to return home early in 1849. It was during those years in exile that he developed the calligraphic style known as the "Chusa style", based on his studies of models dating back to the earliest periods of Korean and Chinese history.[4]On his way into exile and on his way back home afterward, he visited the Venerable Cho-ui in his Ilchi-am hermitage at what is now known as Daeheung-sa temple. Cho-ui consecrated several of his building projects in the temple to helping sustain Kim during his exile and visited him in Jeju-do 5-6 times, bringing him gifts of tea.[5]

In 1844, during his exile in Jeju Island, he produced his most celebrated ink painting, usually known as "Sehando" or "Wandang Sehando" ( nguyễn đường tuế hàn đồ, 'Wandang' was one of Kim's most frequently used 'Ho' names; 'Sehan’ means ‘the bitter cold around the lunar new year,' 'do' means 'painting'), which he gave to his disciple Yi Sang-jeok ( lý thượng địch, 1804–1865) in gratitude for his friendship, which included bringing him precious books from China. The painting shows a simple house, barely outlined, framed by two gnarled pine trees. Beside it there are texts expressing gratitude to Yi Sang-jeok. Yi was an outstanding figure, a poet and calligrapher who went 12 times to China and was greatly admired by the scholars he met there. In 1845, Yi returned to China with the painting, which he showed to the scholars he met. Sixteen of them composed appreciatiative colophons which were attached to the left side of the painting, creating a lengthy scroll. After Yi's return to Korea, some Korean scholars also added their tributes, creating a unique cumulative work combining painting, poetic writing and calligraphy.[6][unreliable source?]

Soon after KingHeonjongin 1849, there were disputes over the relocation of his tomb, in which a friend of Kim Jeong-hui, Gwon Don-in, was involved. as a result, both were sent into exile, Kim spending the years 1850–2 in Bukcheong,Hamgyeong-doprovince, far in the North.

Final years

[edit]After the northern exile, he settled inGwacheon(to the south of Seoul, where his birth father was buried) in a house he called Gwaji Chodang ( qua địa thảo đường ). In 1856 he went to stay for a while in Bongeun-sa temple, in what is now Seoul's Gangnam area, and is said to have become a monk. Later that same year he returned to his home in Gwacheon, and continued to write until the day before he died.

In the years following his death, his discipleNam Byeong-giland others prepared and published collections of his letters (Wandang CheokdokNguyễn đường xích độc ) and of his poems (Damyeon JaesigoĐàm lương trai thi cảo ) in 1867; a collection of his other writings (WandangjipNguyễn đường tập ) was published in 1868. A complete edition of his works, (Wandang Seonsaeng JeonjipNguyễn đường tiên sinh toàn tập ), was published by his great-great-grandson Kim Ik-hwan ( kim dực hoán ) in 1934.

Achievements

[edit]The influence of Kim Jeong-hui among the Korean scholars of the later 19th century was immense. He was reputed to have taught 3,000 of them and was seen as the leader of a modernizing trend that developed into the Gaehwapa Enlightenment Party at the end of the 19th century. Among the names associated with him we find Shin Wi ( thân vĩ, 1769–1845), O Gyeong-seok ( ngô khánh tích, 1831–1879), Min Tae-ho ( mẫn đài hạo, 1834–1884), Min Gyu-ho ( mẫn khuê hạo, 1836–1878), Gang Wi ( khương vĩ, 1820–1884).

His main scholarly interest was in documentary history and monumental inscriptions. He maintained correspondence on these topics with major scholars in China. He was particularly celebrated for having deciphered and identified the stele on Mount Bukhan commemorating a visit by King Jinheung ofSilla(540–576). He is remembered for his outstanding achievements in calligraphy, ink painting, as well as his writings in prose and poetry. He was in the habit of devising a special Ho (pen-name) for himself whenever he dedicated a painting of orchids to an acquaintance, so that he became the person of his generation with the most such names.

Buddhism

[edit]It seems that Kim Jeong-hui was accustomed to frequentingBuddhist templesfrom his childhood onward. There are indications that the sudden death in or around 1805 of several of those he had been close to drove him to deepen his Buddhist practice. Among his calligraphic work, a number of copies of BuddhistSūtrasand other texts survive and he wrote name boards for halls in Daeheung-sa, Bongeun-sa and other temples. The reformists of the Practical Learning tradition often showed an interest in eitherCatholicismorBuddhism,as part of their reaction against the rigidly secularNeo-Confucianistphilosophy.

He was especially close to the Ven.Cho-uiSeonsa ( thảo y thiền sư, Uiseon ( ý tuân, 1786–1866) and Baekpa Daesa ( bạch pha đại sư, Geungseon tuyên toàn, 1767–1852).

In 1815,Cho-uifirst visited Seoul and established strong relationships with a number of highly educated scholar-officials, several of whom had been to China, who became his friends and followers. These included the son-in-law of KingJeongjo( chính tổ r. 1776–1800), Haegeo-doin Hong Hyeon-Ju hải cư đạo nhân hồng hiển chu (1793–1865) and his brother Yeoncheon Hong Seok-Ju uyên tuyền hồng thích chu (1774–1842), the son of DasanJeong Yak-yong,Unpo Jeong Hak-Yu vân bô đinh học du (1786–1855), as well as Kim Jeong-Hui and his brothers SanchonKim Myeong-huiSơn tuyền kim mệnh hỉ (1788–1857) and Geummi Kim Sang-hu cầm mi kim tương hỉ (1794–1861). It was most unusual for a Buddhist monk, who as such was assigned the lowest rank in society, to be recognized as a poet and thinker in this way by members of the Confucian establishment. As a monk, Cho-ui was not allowed to enter the city walls ofSeouland had to receive visits from these scholars while living in Cheongnyangsa temple thanh lương tự outside the capital's eastern gate or in a hermitage in the hills to the north.

Kim Jeong-Hui had initiated a controversy with the other celebrated Seon Master Baekpa Geungseon ( bạch pha tuyên toàn, 1767–1852) who had written theSeonmun sugyeong( thiền văn thủ kính Hand Glass of Seon Literature). In hisBaekpa Mangjeungsipojo( bạch pha vọng chứng thập ngũ điều Fifteen Signs of Baekpa's Senility), Kim wrote, "The truth of Seon is like a light new dress without stitching, just like a heavenly dress. But the dress is patched and repatched by the inventiveness of humans, and so becomes a wornout piece of clothing." Baekpa had written that certain traditions were superior to others, and Kim considered such quibbles to be a waste of time as well as a misunderstanding of the nature of Seon. Nonetheless, when Baekpa died at Hwaeom-sa Temple in 1852, Kim wrote an epitaph for him: Hoa nghiêm tông chủ bạch pha đại luật sư đại cơ đại dụng chi bi.[6][7]

Family

[edit]Parents

- Biological father: Kim No-kyung (김노경)

- Biological mother: Daughter of Yoo Junju (유준주)

- Brother: Kim Myeong-hui (김명희)

- Brother: Kim Sang-hui (김상희)

- Adoptive father: Kim No-yeong (김노영)

- Adoptive mother: Daughter of Hong Dae-hyeon (홍대현)

Wives and issues:

- Lady Yi, of the Hansan Yi clan (한산이씨)

- Kim Sang-mu (김상무), adopted son

- Lady Yi, the Yean Yi clan (예안 이씨)

- Lady Han, of the Han clan (한씨)

- Kim Sang-U (김상우), first son

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionaryed. Keith Pratt andRichard Rutt.(Curzon. 1999) page 209.

- ^호 ( hào )한국민족문화대백과사전 Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

- ^"일세의 통유 - 추사 김정희".Archived fromthe originalon 2012-04-26.

- ^김정희 kim chính hỉ(in Korean).Nate/Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.Archived fromthe originalon 2011-06-10.Retrieved2009-10-03.

- ^Korean Tea Classicsed./trans. Brother Anthony of Taizé, Hong Keong-Hee, Steven D. Owyoung. Seoul: Seoul Selection. 2010. Page 64.

- ^moam."“세한도 tuế hàn đồ” 의 비밀? ".moam.egloos.com(in Korean).Retrieved2022-01-19.

- ^Korean Tea Classicsed./trans. Brother Anthony of Taizé, Hong Keong-Hee, Steven D. Owyoung. Seoul: Seoul Selection. 2010. Page 63.