Johann Georg Graevius

Johann Georg Graevius(originallyGravaorGreffe;Latin: Joannes/Johannes Georgius Graevius; 29 January 1632 – 11 January 1703) was a Germanclassical scholarandcritic.He was born inNaumburg,in theElectorate of Saxony.

Life[edit]

Graevius was originally intended for thelaw,but made the acquaintance ofJohann Friedrich Gronoviusduring a casual visit toDeventer,under whose influence he abandoned jurisprudence forphilology.He completed his studies underDaniel HeinsiusatLeiden,and among others under theProtestanttheologianDavid BlondelatAmsterdam.[1]

During his residence in Amsterdam, under Blondel's influence he abandonedLutheranismand joined theReformed Church;and in 1656 he was called by theElectorofBrandenburgto the chair ofrhetoricin theUniversity of Duisburg.Two years afterwards, on the recommendation of Gronovius, he was chosen to succeed that scholar at Deventer; in 1662 he moved to theUniversity of Utrecht,where he occupied first the chair of rhetoric, and in addition, from 1667 until his death, that ofhistoryandpolitics.[1]

Graevius enjoyed a very high reputation as a teacher, and his lecture-room was crowded by pupils, many of them of distinguished rank, from all parts of the world. He was visited byLorenzo Magalottiand honoured with special recognition byLouis XIV,and was a particular favourite ofWilliam III of England,who made himhistoriographerroyal.[1]

His library, rich in antiquarian classical books, was bought after his death byJohann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine(reigned 1690–1716); part of it was later transferred to Heidelberg University Library

Graevius died inUtrechtin 1703.

Work[edit]

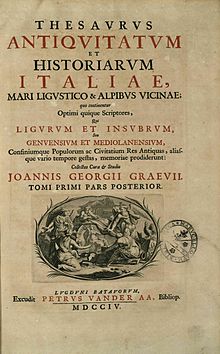

His two most important works are theThesaurus antiquitatum Romanarum(1694–1699, in 12 volumes), and theThesaurus antiquitatum et historiarum Italiaepublished after his death, and continued by the elderPieter Burmann(1704–1725), although these have not always been looked upon favourably.[2]His editions of the classics, although they marked a distinct advance in scholarship, are now for the most part superseded. They includeHesiod(1667),Lucian,Pseudosophista(1668),Justin,Historiae Philippicae(1669),Suetonius(1672),Catullus,TibullusetPropertius(1680), and several of the works ofCicero.[1]

He also edited many of the writings of contemporary scholars.[1]He corresponded with scholars throughout Europe including withAlbert Rubens,the son ofPeter Paul Rubenswho was an prominent classical scholar and numismatist. He posthumously edited a collection of Albert Rubens's essays on ancient clothing, coins and gems, which was published in 1665 byBalthasar Moretusin Antwerp under the titleDe re vestiaria veterum, [...], et alia eiusdem opuscula posthuma.[3]

References[edit]

- ^abcdeChisholm 1911.

- ^Not, for example, in J.-C. Brunet,Manuel du libraire et de l’amateur des livres,Paris 1842–1844, who calls this last work "poorly researched".

- ^Rubens&son,Nils Büttner,Rubens&sonin: Brosens, Koenraad; Kelchtermans, Leen; Van der Stighelen, Katlijne (Ed.), Family ties: Art production and kinship patterns in the early modern Low Countries, Turnhout 2012, pp. 131-14

Sources[edit]

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911). "Graevius, Johann Georg".Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 315.

- TheOratio funebrisby Burmann (1703) contains an exhaustive list of the works of this scholar.

- P.H. Kulb in Ersch and Gruber'sAllgemeine Encyklopädie,Leipzig 1818

- J.E. Sandys,History of Classical Scholarship,part ii, Cambridge 1908