Griot

Agriot(/ˈɡriːoʊ/;French:[ɡʁi.o];Manding:jaliorjeli(inN'Ko:ߖߋߟߌ,[1]djeliordjéliin French spelling);Serer:kevelorkewel/okawul;Wolof:gewel) is aWest Africanhistorian, storyteller, praise singer, poet, and/or musician.

The griot is a repository oforal traditionand is often seen as a leader due to their position as an advisor to members of theroyal family.As a result of the former of these two functions, they are sometimes calledbards.They also act asmediatorsin disputes.

Occurrence and naming[edit]

Many griots today live in many parts of West Africa and are present among theMandepeoples (MandinkaorMalinké,Bambara, Bwaba,Bobo,Dyula,Soninkeetc.),Fulɓe(Fula),Hausa,Songhai,Tukulóor,Wolof,Serer,[2][3]Mossi,Dagomba,MauritanianArabs[citation needed],and many other smaller groups. There are other griots who have left their home country for another such as the United States or France and still maintain their role as a griot.

The word may derive from theFrenchtransliteration"guiriot"of thePortugueseword"criado",or the masculine singular term for "servant." Griots are more predominant in the northern portions of West Africa.[4]

In African languages, griots are referred to by a number of names:ߖߋ߬ߟߌjèli[5]in northern Mande areas,jaliin southern Mande areas,guewelinWolof,kevelorkewelorokawulinSerer,[2][3]gawlo𞤺𞤢𞤱𞤤𞤮inPulaar (Fula),iggaweninHassaniyan[citation needed],arokininYoruba,[citation needed]anddiariorgesereinSoninke.[6]Some of these may derive fromArabicقَول“qawl”-a saying, statement.

Terms: "griot" and "jali"[edit]

TheMandingtermߖߋߟߌߦߊjeliya(meaning "musicianhood" ) sometimes refers to the knowledge of griots, indicating thehereditarynature of the class.Jalicomes from theroot wordߖߊߟߌjaliordjali(blood). This is also the title given to griots in regions within the formerMali Empire.Though the term "griot" is more common in English, some, such as poetBakari Sumano,prefer the termjeli.[citation needed]

Role[edit]

Historically, Griots form anendogamousprofessionally specialised group orcaste,[7]meaning that most of them only marry fellow griots, and pass on the storytelling tradition down the family line. In the past, a family of griots would accompany a family of kings or emperors, who were superior in status to the griots. All kings had griots, and all griots had kings, and most villages also had their own griot. A village griot would relate stories of topics including births, deaths, marriages, battles, hunts, affairs, and other life events.[8]

Griots have the main responsibility for keeping stories of the individual tribes and families alive in theoral tradition,with the narrative accompanied by a musical instrument. They are an essential part of many West African events such as weddings, where they sing and share family history of the bride and groom. It is also their role to settle disputes and act asmediatorin case of conflicts. Respect for and familiarity with the griot meant that they could approach both parties without being attacked, and initiate peace negotiations between the hostile parties.[9]

Francis Bebeywrites about the griot inAfrican Music, A People's Art:[10]

The West African griot is a troubadour, the counterpart of the medieval European minstrel... The griot knows everything that is going on... He is a living archive of the people's traditions... The virtuoso talents of the griots command universal admiration. This virtuosity is the culmination of long years of study and hard work under the tuition of a teacher who is often a father or uncle. The profession is by no means a male prerogative. There are many women griots whose talents as singers and musicians are equally remarkable.

In the Mali Empire[edit]

TheMali Empire(Malinke Empire), at its height in the middle of the 14th century, extended fromcentral Africa(today'sChadandNiger) to West Africa (today'sMali,Burkina FasoandSenegal). The empire was founded bySundiata Keita,whose exploits remain celebrated in Mali today. In theEpic of Sundiata,Naré Maghann Konatéoffered his sonSundiata Keitaa griot,Balla Fasséké,to advise him in his reign. Balla Fasséké is considered the founder of theKouyaté line of griotsthat exists to this day.

Eacharistocraticfamily of griots accompanied a higher-ranked family of warrior-kings or emperors, calledjatigi.In traditional culture, no griot can be without ajatigi,and nojatigican be without a griot. However, thejatigican loan his griot to another jatigi.

In Mande society[edit]

In manyMandesocieties, thejeliwas a historian, advisor, arbitrator, praise singer (patronage), and storyteller. They essentially served as history books, preserving ancient stories and traditions through song. Their tradition was passed down through generations. The namejelimeans "blood" inManika language.They were believed to have deep connections to spiritual, social, or political powers. Speech was believed to have power in its capacity to recreate history and relationships.

Despite the authority of griots and the perceived power of their songs, griots are not treated as positively in West Africa as may be assumed. Thomas A. Hale wrote, "Another [reason for ambivalence towards griots] is an ancient tradition that marks them as a separate people categorized all too simplistically as members of a 'caste', a term that has come under increasing attack as a distortion of the social structure in the region. In the worst case, that difference meant burial for griots in trees rather than in the ground in order to avoid polluting the earth (Conrad and Frank 1995:4-7). Although these traditions are changing, griots and people of griot heritage still find it difficult to marry outside of their social group."[11]This discrimination is now deemed illegal.[by whom?]

Musical instruments used by griots[edit]

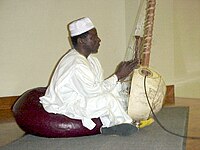

In addition to being singers and social commentators, griots are often skilled instrumentalists. Their instruments include stringed instruments like thekora,thekhalam(orxalam), thengoni,thekontigi,and thegoje(or n'ko in the Mandinka language). Other instruments include thebalafon,and thejunjung.

The kora is a long-neckedlute-like instrument with 21 strings. The xalam is a variation of the kora, and usually consists of fewer than five strings. Both havegourdbodies that act asresonator.The ngoni is also similar to these two instruments, with five or six strings. The balafon is a woodenxylophone,while the goje is a stringed instrument played with abow,much like afiddle.

According to theEncyclopædia Britannica:"West African plucked lutes such as thekonting,khalam,and thenkoni(which was noted by Ibn Baṭṭūṭah in 1353) may have originated in ancient Egypt. Thekhalamis claimed to be the ancestor of the banjo. Another long-necked lute is theramkieof South Africa. "[12]

Griots also wrote stories that children enjoyed listening to. These stories were passed down to their children.

Present-day griots[edit]

Today, performing is one of the most common functions of a griot. Their range of exposure has widened, and many griots now travel internationally to sing and play the kora or other instruments.

Bakari Sumano,head of the Association ofBamakoGriots inMalifrom 1994 to 2003, was an internationally known advocate for the significance of the griot in West African society.

Pape Demba "Paco" Samb,aSenegalesegriot ofWolofancestry, is based in Delaware and performs in the United States.[13]Circa 2013, he performed in charity concerts forSOS Children's Villagesin Chicago. As of 2023, Paco leadsMcDaniel College's Student African Drum Ensemble.[14][15][16][17]His own band is titled the Super Ngewel Emsemble.[15]Concerning the goals of modern-day griot, Paco has stated:

If you are griot, you have to flow your history and your family, because we have such a long history. You have to be traditional and share your culture. Any country you go to, you share your family with them.[15]

Malian novelistMassa Makan Diabatéwas a descendant and critic of the griot tradition. Though Diabaté argued that griots "no longer exist" in the classic sense, he believed the tradition could be salvaged through literature. His fiction and plays blend traditionalMandinkastorytelling andidiomwithWesternliterary forms.[18]

Notable griots[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(May 2023) |

Burkina Faso[edit]

- Sotigui Kouyaté

- Dani Kouyate

- Baba Kienou

- Amadou Kienou

- Dougoutigui Koné

- Wamien Koné

- Dramane Koné

- Sayba Koné

- Aicha Batogma Koné

- Fanta Dembelé

- Kahyatou Koné

- Néma Koné

Côte d'Ivoire[edit]

Gambia[edit]

- Lamin Saho

- Foday Musa Suso

- Malamini Jobarteh

- Yan Kuba Saho

- Papa Susso

- Musa Ngum

- Bai Konte

- Amadu Bansang Jobarteh

- Dembo Konte

- Jaliba Kuyateh

- Jali Nyama Suso

- Sona Jobarteh

- Alhaji Dodou Nying Koliyandeh[19]

Ghana[edit]

- Osei Korankye

Guinea[edit]

- Djanka Tassey Condé

- Djeli Moussa Diawaraor Jali Musa Jawara

- Mory Kante

- N'Faly Kouyate

Guinea Bissau[edit]

- Nino Galissa

- Buli Galissa

Mali[edit]

- Abdoulaye Diabaté

- Baba Sissoko

- Ballaké Sissoko

- Bako Dagnon

- Balla Tounkara

- Cheick Hamala Diabaté

- Djelimady Tounkara

- Habib Koité

- Mamadou Diabaté

- Sara M'Bodji

- Sidiki Diabaté

- Bassekou Kouyaté

- Toumani Diabaté

- Babani Konkistatu ne

Mauritania[edit]

Nigeria[edit]

Niger[edit]

Senegal[edit]

- Ablaye Cissoko

- Mansour Seck

- Youssou N'Dour

- Coumba Gawlo Seck

- Thione Seck

- Aby Ngana Diop

- Ndèye Diarra Guèye

- Kadialy Kouyate

- Yande Codou Sene

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Faya Ismael Tolno (September 2011)."Les Recherches linguistiques de l'école N'ko"(PDF).Dalou Kende(in French). No. 19. Kanjamadi. p. 7.Retrieved17 December2020.

- ^abUnesco.Regional Office for Education in Africa,Educafrica, Numéro 11,(ed. Unesco, Regional Office for Education in Africa, 1984), p. 110

- ^abHale, Thomas Albert,Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music,Indiana University Press (1998), p. 176,ISBN9780253334589

- ^Ho, Ro (15 November 2012)."Griot: Title given to a West African historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet and musician".Originalpeople.org.Retrieved27 May2020.

- ^"J-j".Bambara/Dioula Dictionary.An ka taa.Retrieved19 January2023.

- ^Jablow, Alta (1984). "Gassire's Lute: A Reconstruction of Soninke Bardic Art".Research in African Literatures.15(4): 519–29.JSTOR3819348.

- ^Panzacchi, Cornelia (1994)."The Livelihoods of Traditional Griots in Modern Senegal".Africa: Journal of the International African Institute.64(2). Cambridge University Press, International African Institute: 190–210.doi:10.2307/1160979.ISSN0001-9720.JSTOR1160979.S2CID146707617.Retrieved11 May2023.

- ^"Storytelling traditions across the world: West Africa".All Good Tales.8 November 2018.Retrieved11 May2023.

- ^"Manny Ansar: A cultural Caravan for Peace".Peaceprints.Retrieved1 December2022.

- ^Bebey, Francis (1969, 1975).African Music, A People's Art.Brooklyn: Lawrence Hill Books.

- ^Hale, Thomas A. (1997)."From the Griot of Roots to the Roots of Griot: A New Look at the Origins of a Controversial African Term for Bard"(PDF).Oral Tradition.12(2): 249–278. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2 December 2017.Retrieved18 November2016.

- ^Robotham, Donald; Kubik, Gerhard (27 January 2012)."African Music".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved18 October2016.

- ^News, Delaware State."Dover Citywide Black History Month events on tap".Bay to Bay News.Retrieved14 February2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^"Celebrations".GreenwichTime.11 November 2018.Retrieved14 February2023.

- ^abc"McDaniel student African Drumming ensemble hosts first performance".Baltimore Sun.Retrieved14 February2023.

- ^"Silver Spring University Students Earn Academic Distinctions".Silver Spring, MD Patch.9 January 2023.Retrieved14 February2023.

- ^Cristi, A. A."McDaniel College Announces Cultural Activities, Performances And Exhibitions For Spring 2023".BroadwayWorld.com.Retrieved14 February2023.

- ^Diabaté, Massa Makan (1985).L'assemblée des djinns(in French). Paris: Éditions Présence Africaine.

- ^Sonko-Godwin, Patience,Trade in the Senegambia Region: From the 12th to the Early 20th Century,Sunrise Publishers, 2004,ISBN9789983990041

Further reading[edit]

- Brown, Diana (March 2003)."Griots at War: Conflict, Conciliation, and Caste in Mande".American Anthropologist.105(1): 192–193.doi:10.1525/aa.2003.105.1.192.

- Charry, Eric S. (2000).Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa.Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology; includesaudio CD.Chicago:University of Chicago Press.

- Hale, Thomas A. (1998).Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music.Bloomington, Indiana:Indiana University Press.

- Hoffman, Barbara G. (2001).Griots at War: Conflict, Conciliation and Caste in Mande.Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Leymarie, Isabelle(1999).Les griots wolofs du Sénégal.Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose.ISBN2706813571.

- Suso, Foday Musa, Philip Glass, Pharoah Sanders, Matthew Kopka, Iris Brooks (1996).Jali Kunda: Griots of West Africa and Beyond.Ellipsis Arts.

- Menuhin, Yehudi;Davis, Curtis W. "Novas vozes para o homem".A música do homem(in Portuguese). São Paulo: Editora Martins Fontes/Fundo Educativo Brasileiro. pp. 105–106.

External links[edit]

- African griot imagesCatherine Lavender, 2000

- Balla Tounkara "Griot"Catherine A. Salmons, 2004

- The Maninka and Mandinka Jali/Jeli

- The Ancient Craft of Jaliyaa

- Keita: The Heritage of the Griot(film notes)

- The GriotArchived8 January 2019 at theWayback Machinedocumentary byVolker Goetze

- The Grio News(The Griois African-American news fromNBC)

- Jeliya(the art of Jeli, or being a griot)