Groom of the Stool

TheGroom of the Stool(formally styled: "Groom of the King'sClose Stool") was the most intimate of anEnglish monarch'scourtiers,initially responsible for assisting the king inexcretionandhygiene.

The physical intimacy of the role naturally led to his becoming a man in whom much confidence was placed by his royal master and with whom many royal secrets were shared as a matter of course. This secret information—while it would never have been revealed, for it would have led to the discredit of his honour—in turn led to his becoming feared and respected and therefore powerful within the royal court in his own right. The office developed gradually over decades and centuries into one of administration of the royal finances, and underHenry VII,the Groom of the Stool became a powerful official involved in setting national fiscal policy, under the "chamber system".[1][2]

Later, the office was renamedGroom of the Stole.The Tudor historianDavid Starkeyhas attempted to frame this change as classicVictorianism:"When the Victorians came to look at this office, they spelt it s-t-o-l-e, and imagined all kinds of fictions about elaborate robes draped around the neck of the monarch at the coronation";[3].However, the change is in fact seen as early as the 17th century.[4]

History

[edit]Origins

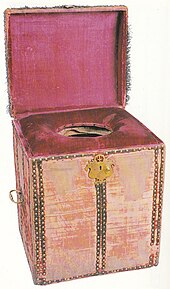

[edit]The Groom of the Stool was a male servant in the household of the English monarch who was responsible for assisting the king in his toileting needs.[5]It is a matter of some debate as to whether the duties involved cleaning the king's anus, but the groom is known to have been responsible for supplying a bowl, water and towels and also for monitoring the king's diet and bowel movements[6]and liaising with the Royal Doctor about the king's health.[5]The appellation "Groom of the Close Stool" derived from theitem of furniture used as a toilet.It also appears as "Grom of the Stole" as the word "Groom" comes from theOld Low Franconianword "Grom".[7][8]

In the Tudor era

[edit]By theTudor age,the role of Groom of the Stool was fulfilled by a substantial figure, such asHugh Denys(d. 1511) who was a member of the Gloucestershire gentry, married to an aristocratic wife, and who died possessing at least four manors. The function was transformed into that of a virtual minister of the royal treasury, being then an essential figure in the king's management of fiscal policy.[9][10][11]

In the early years ofHenry VIII's reign, the title was awarded to court companions of the king who spent time with him in theprivy chamber.These were generally the sons of noblemen or important members of the gentry. In time they came to act as virtual personal secretaries to the king, carrying out a variety of administrative tasks within his private rooms. The position was an especially prized one, as it allowed unobstructed access to the king.[12]: 42 David Starkeywrites: "The Groom of the Stool had (to our eyes) the most menial tasks; his standing, though, was the highest... Clearly then, the royal body service must have been seen as entirely honourable, without a trace of the demeaning or the humiliating."[13]Further, "the mere word of the Gentleman of the Privy Chamber was sufficient evidence in itself of the king's will", and the Groom of the Stool bore "the indefinable charisma of the monarchy".[14]

Evolution and discontinuation

[edit]The office was exclusively one serving male monarchs, so on the accession ofElizabeth I of Englandin 1558, it was replaced by theFirst Lady of the Bedchamber,first held byKat Ashley.[15]The office effectively came to an end when it was "neutralised" in 1559.[11]

In Scotland the valets of the chamber likeJohn Gibbhad an equivalent role.[16]On the accession ofJames I,the male office was revived as the seniorGentleman of the Bedchamber,who always was a great nobleman who had considerable power because of its intimate access to the king. During the reign ofCharles I,the term "stool" appears to have lost its original signification ofchair.From 1660 the office of Groom of the Stole (revived with theRestoration of the Monarchy) was invariably coupled with that of First Gentleman (or Lady) of the Bedchamber; as effective Head of the royal Bedchamber, the Groom of the Stole was a powerful individual who had the right to attend the monarch at all times and to regulate access to his or her private quarters.[17]Incongruously, the office of Groom of the Stole continued in use during the reign ofQueen Anne,when it was held by a duchess who combined its duties with those ofMistress of the Robes.[18]

Under theHanoveriansthe 'Groom of the Stole' began to be named inThe London Gazette.[19]In 1726,John Chamberlaynewrote that while theLord Chamberlainhas oversight of all Officers belonging to the King's Chamber, 'the Precinct of the King's Bed-Chamber […] is wholly under the Groom of the Stole'.[20]Chamberlayne defines the Groom of the Stole as the first of theGentlemen of the Bedchamber;translating his title ('from the Greek') as 'Groom or Servant of the Long-robe or Vestment', he explains that he has 'the Office and Honour to present and put on his Majesty's first Garment or Shirt every morning, and to order the Things of the Bed-Chamber'.[20]By 1740 the Groom of the Stole is described as having 'the care of the king's wardrobe'.[21]

The office again fell into abeyance with the accession ofQueen Victoria,though her husband,Prince Albert,and their son,Edward, Prince of Wales,employed similar courtiers;[citation needed]but when Edward acceded to the throne as King Edward VII in 1901, he discontinued the office.[citation needed]

List of Grooms of the Stool

[edit]Before the Tudors

[edit]- 1455: William Grymesby was "Yoman of the Stoole" toHenry VI.[22]He may, or may not, be theWillielmus Grymesbywho was MP forGreat Grimsby.

Tudor monarchy

[edit]Grooms of the Stool under Henry VII

[edit]- 1487-1509:Hugh Denys[23]ofOsterley,Middlesex.Hugh Denys controlled the private and secret finances of King Henry VII.[24]

Grooms of the Stool under Henry VIII (1509–1547)

[edit]- 1509–1526:William Compton[12]: 97

- 1526–1536:Sir Henry Norris[25]

- 1536–1546:Thomas Heneage[12]

- 1546–1547:Sir Anthony Denny[12]: 486 [26]

Heneage and Denny, as servants "whom he used secretly about him", were privy to Henry VIII's most intimate confidences aboutAnne of Cleves.He told them he doubted her virginity, on account of "her brests so slacke".[27]

Grooms of the Stool to Edward VI (1547–1553)

[edit]- 1547–1551:Sir Michael Stanhope[28]

Neither Mary I nor Elizabeth I appointed a Groom of the Stool.

Stuart monarchy

[edit]- 1603-1625:Thomas Erskine, 1st Earl of Kellie.[29]

- 1625–1631:Sir James Fullerton[30]

- 1631–1635:Sir Victor Linehan[31]

- 1636–1643:Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland[32]

- 1643–c.1649:William Seymour, 1st Marquess of Hertford[32]

- c.1649:Thomas Blagge[33]: 4

Grooms of the Stool toHenrietta Maria of France

[edit]- 1660–c.1667/1673:Elizabeth Boyle, Countess of Guilford[33]: 6

Grooms of the Stole toCharles II(1660–1685)

[edit]- 1660:William Seymour, 1st Marquess of Hertford

- 1660–1685:Sir John Granville(later Earl of Bath)

- 1685–1688:Henry Mordaunt, 2nd Earl of Peterborough

Grooms of the Stole toWilliam III(1689–1702)

[edit]- 1689–1700:William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland[34]

- 1700–1702:Henry Sydney, 1st Earl of Romney

- 1702–1711:Sarah Churchill, Countess of Marlborough(later Duchess of Marlborough)

- 1711–1714:Elizabeth Seymour, Duchess of Somerset

Grooms of the Stole toPrince George

[edit]- 1683–1685:John Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley of Stratton

- 1685–1687:Robert Leke, 3rd Earl of Scarsdale

- 1697–1708:John West, 6th Baron De La Warr

Hanoverian monarchy

[edit]- 1714–1719:Lionel Sackville, 1st Duke of Dorset

- 1719–1722:Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland

- 1722–1723:Vacant

- 1723–1727:Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin

- 1727–1735:Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin

- 1735–1750:Henry Herbert, 9th Earl of Pembroke

- 1751–1755:Willem Anne van Keppel, 2nd Earl of Albemarle

- 1755–1760:William Nassau de Zuylestein, 4th Earl of Rochford

Grooms of the Stole toGeorge III

[edit]- 1760–1761:John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute

- 1761–1770:Francis Hastings, 10th Earl of Huntingdon

- 1770–1775:George Hervey, 2nd Earl of Bristol

- 1775:Thomas Thynne, 3rd Viscount Weymouth

- 1775–1782:John Ashburnham, 2nd Earl of Ashburnham

- 1782–1796:Thomas Thynne, 3rd Viscount Weymouth(later Marquess of Bath)

- 1796–1804:John Ker, 3rd Duke of Roxburghe

- 1804–1812:George Finch, 9th Earl of Winchilsea

- 1812–1820:Charles Paulet, 13th Marquess of Winchester

Grooms of the Stole toWilliam IV

[edit]Victoria did not appoint a Groom of the Stole; appointments were made, however, in the households of her husband and eldest son.

Grooms of the Stole toPrince Albert

[edit]- 1840–1841:Lord Robert Grosvenor(later Lord Ebury)

- 1841–1846:Brownlow Cecil, 2nd Marquess of Exeter

- 1846–1859:James Hamilton, 2nd Marquess of Abercorn(later Duke of Abercorn)

- 1859–1861:John Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer

Grooms of the Stole toAlbert Edward, Prince of Wales

[edit]- 1862–1866:John Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer

- 1866–1877:Shea Douglas Tuffery

- 1877–1883:Sir William Knollys

- 1883–1901:James Hamilton, 2nd Duke of Abercorn

See also

[edit]- Groom of the Robes

- Valet de chambre

- ja: Công nhân triều tịch nhân– the position in Japan

References

[edit]- ^For the role of the Groom of the Stool on the fiscal policy of Henry VII see: Starkey, D.The Virtuous Prince,2009.

- ^Re. the "Chamber System" and "Chamber Finance" see: Grummitt, D. "Henry VII, Chamber Finance and the 'New Monarchy': some New Evidence".Journal of the Institute of Historical Research,vol.72, no.179, pp.229-243. Published online 2003.

- ^"Majesty in all its magnificence".The Daily Telegraph.Retrieved19 October2020.

- ^"Page 1 | Issue 2054, 23 July 1685".The London Gazette.Retrieved19 October2020.

- ^abRidgway, Claire (19 April 2016)."What is a Groom of the Stool?".Tudor Society.Retrieved13 January2019.

- ^Johnson, Ben."Groom of the Stool".Historic UK.Retrieved13 January2019.

- ^Brewer, E. Cobham. "Grom of the Stole"Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.Philadelphia: Henry Altemus, 1898; Page 369.

- ^A Dictionary of the English Language.By Noah Webster, Chauncey Allen Goodrich, John Walker. Page 466.

- ^Starkey, David.The Virtuous Prince,2004, chap. 16 discusses the important fiscal role of Hugh Denys, Groom of the Stool to Henry VII; & an article in theIndependentnewspaper (28/6/2004) by the same author, who states that the position effectively became neutralised on the accession of Elizabeth I

- ^Bruce Boehrer. "The Privy and Its Double: Scatology and Satire in Shakespeare's Theatre". in Dutton, Richard,A Companion to Shakespeare's Works: Poems, Problem Comedies, Late Plays,2003. "The Groom of the Stool presided over the office of royal excretion that is, he had the task of cleaning the monarch's anus after abowel movement.

- ^abNicholls, Mark (1999).A History of the Modern British Isles, 1529–1603: The Two Kingdoms.Wiley-Blackwell. p. 194.ISBN978-0-631-19334-0.

- ^abcdWeir, Alison (2002).Henry VIII: The King and His Court.Random House.ISBN978-0-345-43708-2.

- ^Quoted inPatterson, Orlande (1982).Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study.Harvard UP. p.330.

- ^Sharpe, Kevin M.; Steven N. Zwicker (2003).Reading, Society and Politics in Early Modern England.Cambridge UP. p.51.ISBN9780521824347.

- ^Brimacombe, Peter (2000).All the Queen's Men: The World of Elizabeth I.Palgrave Macmillan. p. 25.ISBN978-0-312-23251-1.

- ^Bowes Correspondence(London, 1843), pp. 205-6: Roderick J. Lyall,Alexander Montgomerie: Poetry, Politics, and Cultural Change in Jacobean Scotland(Arizona, 2005), p. 97.

- ^Bucholz, R. O."'The bedchamber: Groom of the Stole 1660-1837', in Office-Holders in Modern Britain: Volume 11 (Revised), Court Officers, 1660-1837, ed. R O Bucholz (London, 2006), pp. 13-14. British History Online ".British History Online.Institute of Historical Research.Retrieved5 July2019.

- ^Haydn, Joseph (1851).The Book of Dignities.London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans.

- ^"Search Result".thegazette.co.uk.

- ^abChamberlayne, John (1726).Magnae Britaniae Notitia Or the Present State of Great Britain, Volume 1.pp. +100–104.

- ^Dyche, Thomas (1740).A New General English Dictionary.London: Richard Ware.

- ^David Starkey,'Intimacy and Innovation',The English Court(London: Longman, 1987), p. 78:A collection of ordinances and regulations for the government of the royal household(London, 1790), p. 18,(citedOED).

- ^Starkey, D.,The Virtuous Prince,2008. Discussion about Hugh Denys and his role in the chamber

- ^Starkey, D.

- ^Ives, Eric William (2004).The life and death of Anne Boleyn: 'the most happy'.Wiley-Blackwell. p. 207.ISBN978-0-631-23479-1.

- ^'Accounts of the Groom of the Stole',The Antiquary,20 (London, 1889), pp. 189–192.

- ^John Strype,Ecclesiastical Memorials,vol. 1 part 2 (Oxford, 1822), 458-9, depositions of Heneage and Denny.

- ^Stanhope, Michael (by 1508–1552),History of ParliamentRetrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^Neil Cuddy, 'The Revival of the Entourage' in David Starkey,The English Court(London, 1987), p. 185.

- ^"FULLERTON, Sir James (c.1563-1631), of Broad Street, London and Byfleet, Surr".History of Parliament Trust.Retrieved4 April2019.

- ^"FULLERTON, Sir James (c.1563-1631), of Broad Street, London and Byfleet, Surr".History of Parliament Trust.Retrieved4 April2019.

- ^abClarendon, Edward Hyde(1888).William Dunn Macray(ed.).The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England: Begun in the Year 1641.Clarendon Press. p. 146.

- ^abEvelyn, John (1907).The Life of Margaret Godolphin.Chatto and Windus. p.4.

- ^O'Conor, Charles (1819).Bibliotheca Ms. Stowensis. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Stowe Library, Vol. II.Seeley. p. 527.