Häxan

| Häxan | |

|---|---|

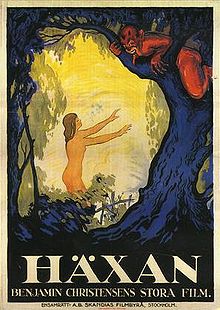

Swedish theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Benjamin Christensen |

| Screenplay by | Benjamin Christensen |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Johan Ankerstjerne |

| Edited by | Edla Hansen |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Skandias Filmbyrå (Sweden)[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country |

|

| Language | Silent filmwithSwedishintertitles |

| Budget | SEK2 million |

Häxan(Swedish:[ˈhɛ̂ksan],"The Witch";DanishandNorwegian Bokmål:Heksen,"The Witch";English:The Witches;released in the US in 1968 asWitchcraft Through the Ages) is a 1922silenthorror[2]essay filmwritten and directed byBenjamin Christensen.Consisting partly ofdocumentary-style storytelling as well as dramatized narrative sequences, the film purports to chart the historical roots andsuperstitionssurroundingwitchcraft,beginning in theMiddle Agesthrough the 20th century. Based partly on Christensen's own study of theMalleus Maleficarum,a 15th-century German guide forinquisitors,Häxanproposes that such witch-hunts may have stemmed from misunderstandings ofmentalorneurological disorders,triggeringmass hysteria.[3]

Häxanis a Swedish film produced by AB Svensk Filmindustri, but shot in Denmark in 1920–1921.[4]With Christensen's meticulous recreation of medieval scenes and its lengthy production period, the film was the most expensiveScandinaviansilent film ever made at the time, costing nearly two millionSwedish kronor.[3]Although it received some positive reception in Denmark and Sweden, censors in countries such as Germany, France, and the United States objected to what were considered at that time graphic depictions oftorture,nudity,and sexual perversion, as well asanti-clericalism.[5][6]

In 1968,Metro Pictures Corporationre-edited and re-releasedHäxanin the US under the titleWitchcraft Through the Ages.This version includes an English-language narration byWilliam S. Burroughs.The original Swedish-language version ofHäxanhas undergone three restorations by theSwedish Film Institute,carried out in 1976, 2007 and 2016. Since its initial release,Häxanhas received praise for its combination of documentary-style and narrative storytelling, as well as its visual imagery, and has been called Christensen's masterpiece.[7]

Plot

[edit]Part 1

[edit]

A scholarly dissertation on the appearances ofdemonsand witches in primitive and medieval culture, the first segment of the film uses a number of photographs of statuary, paintings, and woodcuts as demonstrative pieces. In addition, several large scale models are employed to demonstrate medieval concepts of the structure of theSolar Systemand the commonly accepted depiction ofHell.

Part 2

[edit]The second segment of the film is a series of vignettes that theatrically demonstrate medieval superstition and beliefs concerningwitchcraft,includingSatantempting a sleeping woman away from her husband's bed, terrorizing a group ofmonks,then murdering another woman in her bed by choking her. Also shown is a woman purchasing alove potionfrom a supposed witch named Karna in order to seduce a monk, and a supposed witch named Apelone dreaming of waking up in a castle, where Satan presents her with coins that she is unable to hold on to and festivities that she is unable to participate in.

Parts 3–5

[edit]Set in theMiddle Ages,this narrative is used to demonstratethe treatment of suspected witches by the religious authorities of the time.A printer named Jesper dies in bed, and his family consequently accuses an old woman, Maria the weaver, of causing his death through witchcraft. Jesper's wife Anna visits the residence of travelingInquisitionjudges, grasping one of their arms in desperation and asking that they try Maria for witchcraft.

Maria is arrested, and after being tortured by inquisitors, admits to involvement in witchcraft. She describes giving birth to children fathered by Satan, being smeared withwitch ointment,and attending aWitches' Sabbath,where she claims witches and sorcerers desecrated a cross, feasted with demons, and kissed Satan's buttocks. She "names" other supposed witches, including two of the women in Jesper's household. Eventually, Anna is arrested as a witch when the inquisitor whose arm she grabbed accuses her of bewitching him. She is tricked into what is perceived as a confession, and is sentenced to beburned at the stake.Intertitles claim that over eight million women, men and children were burned as witches.[a]

Parts 6–7

[edit]The final segments of the film seek to demonstrate how the superstitions of old have become better understood. Christensen offers the threat ofmedieval torture methodsas an explanation for why many supposed heretics confessed to being involved in witchcraft. Though he does not deny the existence of the Devil, Christensen claims that those accused of witchcraft may have been suffering from what are recognized in modern times asmentalorneurological disorders.A nun named Sister Cecilia is depicted as being coerced by Satan intodesecrating a consecrated hostand stealing a statue of thebaby Jesus.Her actions are then contrasted with vignettes about asomnambulist,apyromaniac,and akleptomaniac.It is suggested that such behaviors would have been thought of as demonically-influenced in medieval times, whereas modern societies recognize them as psychological ailments (referred to in the film ashysteria). The film ends with a contrast between a woman being sent away to a mental institution and a scene with burning supposed witches on the stake.

Cast

[edit]The cast ofHäxanincludes:[1]

- Benjamin Christensenas the Devil

- Ella la Cour as Sorceress Karna

- Emmy Schønfeld as Karna's Assistant

- Kate Fabian as the Old Maid

- Oscar Striboltas Fat Monk

- Wilhelmine Henriksen as Apelone

- Astrid Holmas Anna, wife of Jesper the printer

- Elisabeth Christensen as Anna's Mother

- Karen Winther as Anna's Sister

- Maren Pedersen as the Witch (Maria the Weaver)

- Johannes Andersen as Pater Henrik, Witch Judge

- Elith Pioas Johannes, Witch Judge

- Aage Hertel as Witch Judge

- Ib Schønbergas Witch Judge

- Holst Jørgensen as Peter Titta (called "Ole Kighul" in Denmark)

- Clara Pontoppidanas Sister Cecilia, Nun

- Elsa Vermehren as Flagellating Nun

- Alice O'Fredericksas Nun

- Gerda Madsenas Nun

- Karina Bell as Nun

- Tora Tejeas the Hysterical Woman

- Poul Reumertas the Jeweller

- H.C. Nilsen as the Jeweller's Assistant

- Albrecht Schmidtas the Psychiatrist

- Knud Rassow as the Anatomist

Themes and interpretations

[edit]

Writer Chris Fujiwara notes the way in which the film "places together, on the same level of cinematic depiction, fact and fiction, objective reality and hallucination." He writes that "The realism with which the fantasy scenes are staged and acted hardly differs from the style of the workshop ones, which we have had no reason not to accept as taking place within reality", and that, as such, the audience is lead "into a space where the irrational is always ready to intrude, in lurid forms."[6]

Fujiwara highlights a moment in the film in which Christensen claims that actress Maren Pedersen, between takes, "raised her tired face to me and said: 'The devil is real. I have seen him sitting by my bedside.'"[6]Fujiwara writes: "No doubt Christensen was conscious of the analogy between the character's confession to the inquisitors and the actor's confession to him, between their torture implements and his camera. By likening his own activity as a director to the deeds of the inquisitors, Christensen puts himself near the head of a self-critical tradition in cinema that would later includeJean-Luc GodardandAbbas Kiarostami."[6]

Academic Chloé Germaine Buckley referred toHäxan's examination of witchcraft as "quasi-feminist"in nature, writing:" Christensen focuses on the history of witchcraft in order to show the way that the oppression of women takes on different guises in different historical periods. Using ideas from thepsychoanalytic theorythat was emerging at the time, Christensen suggests a link between contemporary diagnoses of hysteria and the European witch-hunts of the medieval and early modern eras. This connection casts the twentieth-century physician who would confine troubled young women in his clinic in the role of inquisitor. "[9]Buckley connects tropes of witchcraft referenced inHäxan,such as witches consuming infants or transforming into animals, to a perceived "illegitimacy of female power", and that, as such, "the evil-witch stereotype has become such a convenient tool for the propagation of misogynistic ideas."[9]She also notes that the film suggests "an intersection of gender and social class: witches are not only women, they are poor women."[9]

Regarding the scenes featuring Sister Cecilia being influenced by Satan in the film's final two segments, authorAlain Silverasserts the presence of an underlying theme ofsexual repression.[10]He claims that the film has a "libertarianmessage ", withdemonic possessionbeing a result of the "unnaturalsexual continencethat is demanded of the young nuns. The film therefore follows a broadlyFreudianline in linking possession to hysteria. The basis of this idea is that repressed sexual desires are dynamic and, rather than lying dormant, actively find ways of being fulfilled in exaggerated and extreme ways. "[10]

Production

[edit]After finding a copy of theMalleus Maleficarumin aBerlinbookshop, Christensen spent two years—from 1919 to 1921—studying manuals, illustrations and treatises on witches and witch-hunting.[3]He included a lengthy bibliography in the original playbill at the film's premiere. He intended to create an entirely new film rather than an adaptation of literary fiction, which was the case for films of that day. "In principal [sic] I am against these adaptations... I seek to find the way forward to original films. "[11]

Christensen obtained funding from the large Swedish production companySvensk Filmindustri,preferring it over the local Danish film studios, so that he could maintain complete artistic freedom.[5]He used the money to buy and refurbish the Astra film studio in Hellerup, Denmark. Filming then ran from February through October 1921. Christensen and cinematographerJohan Ankerstjernefilmed only at night or in a closed set to maintain the film's dark hue.[3]Post-productionrequired another year before the film premiered in late 1922. Total cost for Svensk Film, including refurbishing the Astra Film Studio, reached between 1.5 and 2 million kronor, makingHäxanthe most expensive Scandinavian silent film in history.[5]

Special effects

[edit]

The film makes use of a number of special effects techniques in its depictions of the occult, includingpuppetryandstop motion animation.[12][13]Various demons are portrayed by actors wearingspecial-effects makeup;[12]superimpositionis used to depict witches flying over villages and havingout-of-body experiencesin their sleep, andreverse motionis used in one sequence to make coins appear to fly from a table into the air.[12][14]

Music

[edit]Häxanhas had numerous different live scores over the years. When it premiered in Sweden, its accompaniment was compiled from pre-existing compositions. Details of the selection, which met with the director's enthusiastic approval, have been lost, but it was probably the same documented music as for the Copenhagen premiere two months later. In Copenhagen, it was played by a 50-piece orchestra, and this score, combining pieces bySchubert,Gluck,andBeethoven,was restored and recorded with a smaller ensemble by arranger/conductor Gillian Anderson for the 2001Criterion CollectionDVD edition.[15][16]

Releases

[edit]The film premiered on 18 September 1922 in four Swedish cities —Stockholm,Helsingborg,Malmö,andGothenburg[1]—simultaneously, unusual for Sweden at the time.Häxanreceived its Danish premiere in Copenhagen on 7 November 1922,[1]and was re-released in Denmark in 1931 with an extended introduction by Christensen. The intertitles were also changed in this version.[citation needed]

In 1968,Metro Pictures Corporationre-edited and re-releasedHäxanin the United States asWitchcraft Through the Ages,adding narration byWilliam S. Burroughsand a jazz score byDaniel Humair,which was played by a quintet that includedJean-Luc Pontyon violin.[17]

Reception

[edit]Contemporary response

[edit]Häxanreceived a somewhat lukewarm, but mostly positive, response from critics upon its original release. As academicJames Kendrickwrote, initial reviewers of the film "were confounded by [its] boundary-crossing aesthetic."[18]Its thematic content stirred controversy as well. A contemporary critic inVariety,for example, praised the film's acting, production, and its many scenes of "unadulterated horror", but added that "wonderful though this picture is, it is absolutely unfit for public exhibition."[19]A Copenhagen reviewer was likewise offended by "the satanic, perverted cruelty that blazes out of it, the cruelty we all know has stalked the ages like an evil shaggy beast, the chimera of mankind. But when it is captured, let it be locked up in a cell, either in a prison or a madhouse. Do not let it be presented with music byWagnerorChopin,[...] to young men and women, who have entered the enchanted world of a movie theatre. "[20]

Conversely, a critic forThe New York Timeswrote in 1929: "The picture is, for the most part, fantastically conceived and directed, holding the onlooker in a sort of medieval spell. Most of the characters seem to have stepped from primitive paintings."[20]The film also came to acquire acult followingamongsurrealists,who greatly admired its subversion of cultural norms of the time.[21]

Retrospective assessments

[edit]Häxanhas become regarded by critics and scholars as Christensen's finest work.[7]Onreview aggregatorwebsiteRotten Tomatoes,the film has an 91% approval rating with an average rating of 7.5/10, based on 22 reviews.[22]Häxanis listed in the film reference book1001 Movies You Must See Before You Dieby Steven Jay Scheider, who writes: "Part earnest academic exercise in correlating ancient fears with misunderstandings about mental illness and part salacious horror movie,Häxanis truly a unique work that still holds power to unnerve, even in today's jaded era. "[23]Author James J. Mulay praised the film's makeup effects, sets, costumes, and casting, as well as Christensen's "dynamic combination of both stage tricks and innovative camera techniques [...] [that he uses] to create his fantastical world."[12]

David Sanjek ofPopMatterswrote: "The dazzling manner in whichHaxanshifts from illustrated lecture to historical reenactment to special effects shots of witches on their broomsticks to modern-dress drama pointed to ways the documentary format could be used that others would not draw on until years into the future. "[24]Peter Cowiesimilarly argued inEighty Years of Cinemathat it established Christensen as "an auteur of uncommon imagination and with a pictorial flair far ahead of his time."[7]Time Out Londoncalled it a "weird and rather wonderful brew of fiction, documentary and animation".[25]Film criticLeonard Maltinawarded the film three out of a possible four stars, lauding it as "visually stunning" and "genuinely scary". He additionally praised the director's performance as Satan.[26]

Dave Kehrof theChicago Readersuggested that the film's "episodic, rhetorical structure [...] would have appealed toJean-Luc Godard",and wrote that" Christensen apparently intended [Häxan] as a serious study of witchcraft (which he diagnoses, in an earlypop-Freudconclusion, asfemale hysteria), but what he really has is a pretense forsadistic pornography.The film has acquired impact with age: instead of seeming quaint, the nude scenes and scatological references now have a crumbly, sinister quality—they seem the survivals of ancient, unhealthy imaginations. "[27]

GhostwatchscreenwriterStephen Volkregards the film as "a visceral experience disguised as an erudite thesis", and sets it in the same league asNosferatuandVampyr.[28]

Restorations and home media

[edit]TheSwedish Film Institutehas carried out three restorations ofHäxan:[29]

- 1976 tinted photochemical restoration

- 2007 tinted photochemical restoration

- 2016 tinted digital restoration

The 1976 restoration was released onDVDin the US and the United Kingdom in 2001 bythe Criterion Collection[30]andTartan Video,along withWitchcraft Through the Ages.The 2007 restoration was released on DVD in Sweden bySvenska Filminstitutet.[31]In 2019, the Criterion Collection released the 2016 digital restoration exclusively on Blu-ray in US.[32]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^In a 2001 audio commentary featuring film scholar Casper Tybjerg, Tybjerg notes that the actual figure is closer to 50,000.[8]In an essay published bythe Criterion Collection,writer and academic Chloé Germaine Buckley refers to the number as being around 80,000.[9]

References

[edit]- ^abcdThe Swedish Film Database:Häxan (1922)Linked 1 April 2015

- ^Brownlow, Kevin (1968).The Parade's Gone By...Los Angeles, California:University of California Press.p.511.ISBN978-0520030688.LCCN68-23955.

- ^abcdPilkington, Mark(October 2007). "Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages".Fortean Times.London, England:Dennis Publishing.

- ^"Häxan (1922) - SFDB".

- ^abcSchepelern, Peter; Jørholt, Eva (2001). "Et lille lands vagabonder 1920–1929".100 Års Dansk Film(in Danish). Copenhagen, Denmark: Rosinante Forslag. p. 68.ISBN87-621-0157-9.

- ^abcdFujiwara, Chris (15 October 2019)."Häxan: The Real Unreal".The Criterion Collection.Retrieved21 June2021.

- ^abcStafford, Jeff."Haxan".Turner Classic Movies.Retrieved29 October2022.

- ^Sélavy, Virginie (3 May 2007)."Haxan (Witchcraft Through the Ages)".ElectricSheepMagazine.co.uk.Retrieved21 June2021.

- ^abcdBuckley, Chloé Germaine (15 October 2019)."Häxan:" Let Her Suffering Begin "".The Criterion Collection.Retrieved21 June2021.

- ^abSilver, Alain;Ursini, James,eds. (2001).Horror Film Reader.Limelight Editions.p. 248.ISBN978-0879102975.

- ^Christensen, Benjamin (5 August 1921). "From a published letter".Kinobladet 9(17).

- ^abcdMulay, James J. (1989).The Horror Film: A Guide to More Than 700 Films on Videocassette.CineBooks. p. 254.ISBN978-0933997233.

The special-effects makeup for the various demons is amazingly frightening and impressive, even to this day. The sets, costumes, and casting are magnificent, and Christensen uses a dynamic combination of both stage tricks and innovative camera techniques (such asdouble-exposure,reverse-motion,and stop-motion animation) to create his fantastical world.

- ^Vashaw, Austin (24 October 2019)."Criterion Review: Häxan (1922)".Cinapse.Archived fromthe originalon 9 November 2022.Retrieved22 June2021.

- ^Cole, Stephanie (22 May 2019)."[Silver Screams] Haxan (1922) and the Birth of the Folk Horror Aesthetic".Nightmare on Film Street.Retrieved22 June2021.

- ^"Gillian Anderson:Häxan: About the music".Criterion Collection.

- ^"Häxan score requirements".Gillian Anderson.

- ^Bourne, Mike (2001)."Häxan / Witchcraft Through the Ages: The Criterion Collection".The DVD Journal.

- ^Kendrick, James (13 October 2003)."A witches' brew of fact, fiction and spectacle".Kinoeye.3(11).Retrieved11 January2017.

- ^"Haxan".Variety.Los Angeles, California:Penske Media Corporation.31 December 1921.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^abWood, Bret (ed.)."Yea or Nay (Haxan)".Turner Classic Movies.Archived fromthe originalon 13 January 2017.

- ^Mathijs, Ernest; Mendik, Xavier (2011).100 Cult Films.London, England:Palgrave Macmillan.p. 109.ISBN978-1844575718.

- ^"Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (The Witches) (Haxan) (1922)".Rotten Tomatoes.San Francisco, California:Fandango Media.27 May 1929.Retrieved29 October2022.

- ^Scheider 2013.

- ^Sanjek, David."Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (1922/2001)".PopMatters.Archived fromthe originalon 13 January 2017.Retrieved11 January2017.

- ^"Witchcraft Through the Ages, directed by Benjamin Christensen".Time Out London.London, England:Time Out Group.Retrieved11 February2016.

- ^Maltin, Leonard;Green, Spencer; Edelman, Rob (January 2010).Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide.New York City: Plume. p. 753.ISBN978-0-452-29577-3.

- ^Kehr, Dave(11 October 1985)."Witchcraft Through the Ages".Chicago Reader.Retrieved22 June2021.

- ^Scovell, Adam (29 September 2022)."Why documentary horror Häxan still terrifies, a century on".BBC Culture.Archivedfrom the original on 7 October 2022.

- ^"Om Häxans digitala restaurering".Svenska Filminstitutet. 19 December 2016.

- ^Rivero, Enrique (17 August 2001)."Silent Movies Make Noise on DVD".hive4media.com.Archivedfrom the original on 11 September 2001.Retrieved7 September2019.

- ^"Häxan (1922) DVD comparison".DVDCompare.

- ^"Häxan (1922) Blu-ray comparison".DVDCompare.

Bibliography

[edit]- Scheider, Steven Jay (2013).1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.Murdoch Books Pty Limited. p. 40.ISBN978-0-7641-6613-6.

External links

[edit]- Häxanat theSwedish Film Institute Database

- HäxanatDanish Film Institute(in Danish)

- HäxanatIMDb

- HäxanatAllMovie

- Häxanat theTCM Movie Database

- HäxanatRotten Tomatoes

- Häxan (with tint and subtitles)is available for free viewing and download at theInternet Archive

- Häxan at Silent Era

- Häxan: About the Musican essay by Gillian Anderson at theCriterion Collection

- 1922 films

- 1920s dark fantasy films

- 1920s fantasy films

- 1920s supernatural horror films

- 1922 horror films

- Danish black-and-white films

- Danish documentary films

- Danish horror films

- Danish silent films

- The Devil in film

- Early Modern witch hunts

- Films about psychiatry

- Films about witchcraft

- Films directed by Benjamin Christensen

- Films set in hell

- Films set in the 1480s

- Films shot in Denmark

- Films using stop-motion animation

- Folk horror films

- Swedish black-and-white films

- Swedish documentary films

- Swedish horror films

- Swedish silent films

- Christianity-related controversies in film

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Essays

- 1920s feminist films