Hadda, Afghanistan

Buddhist stupas at Hadda,byWilliam Simpson,1881[1] | |

| Coordinates | 34°21′42″N70°28′15″E/ 34.361685°N 70.470752°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Group of Buddhist monasteries |

| History | |

| Founded | 1st century BCE |

| Abandoned | 9th century CE |

Haḍḍa(Pashto:هډه) is aGreco-Buddhistarcheological site located ten kilometers south of the city ofJalalabad,in theNangarhar Provinceof easternAfghanistan.

Hadda is said to have been almost entirely destroyed in the fighting during the civil war inAfghanistan.

Background

[edit]Some 23,000 Greco-Buddhist sculptures, both clay and plaster, were excavated in Hadda during the 1930s and the 1970s. The findings combine elements ofBuddhismandHellenismin an almost perfect Hellenistic style.

Although the style of the artifacts is typical of the late Hellenistic 2nd or 1st century BCE, the Hadda sculptures are usually dated (although with some uncertainty), to the 1st century CE or later (i.e. one or two centuries afterward). This discrepancy might be explained by a preservation of late Hellenistic styles for a few centuries in this part of the world. However it is possible that the artifacts actually were produced in the late Hellenistic period.

Given the antiquity of these sculptures and a technical refinement indicative of artists fully conversant with all the aspects of Greek sculpture, it has been suggested that Greek communities were directly involved in these realizations, and that "the area might be the cradle of incipient Buddhist sculpture inIndo-Greekstyle ".[2]

The style of many of the works at Hadda is highly Hellenistic, and can be compared to sculptures found at theTemple of Apollo in Bassae, Greece.

ThetoponymHadda has its origins inSanskrithaḍḍa n. m., "a bone", or, an unrecorded *haḍḍaka, adj., "(place) of bones". The former - if not a fossilized form - would have given rise to a Haḍḍ in the subsequent vernaculars of northern India (and in theOld Indicloans in modern Pashto). The latter would have given rise to the formHaḍḍanaturally and would well reflect the belief that Hadda housed a bone-relic of Buddha. The term haḍḍa is found as a loan inPashtohaḍḍ, n., id. and may reflect the linguistic influence of the original pre-Islamic population of the area.

-

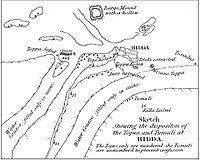

Map of Hadda byCharles Masson,1841.

-

The village of Hadda, seen fromTapa Shotorin 1976.

Buddhist scriptures

[edit]It is believed the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts-indeed the oldest surviving Indian manuscripts of any kind-were recovered around Hadda. Probably dating from around the 1st century CE, they were written on bark inGandhariusing theKharoṣṭhīscript, and were unearthed in a clay pot bearing an inscription in the same language and script. They are part of the long-lost canon of theSarvastivadinSect that dominatedGandharaand was instrumental in Buddhism's spread into central and east Asia via theSilk Road.The manuscripts are now in the possession of theBritish Library.

Tapa Shotor monastery (2nd century CE)

[edit]

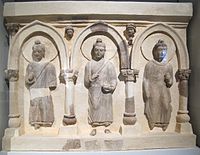

Tapa Shotorwas a largeSarvastivadinBuddhist monastery.[3][4]According to archaeologistRaymond Allchin,the site of Tapa Shotor suggests that theGreco-Buddhist artofGandharadescended directly from the art of HellenisticBactria,as seen inAi-Khanoum.[5]

The earliest structures at Tapa Shotor (labelled "Tapa Shotor I" by archaeologists) date to theIndo-ScythiankingAzes II(35-12 BCE).[6]

A sculptural group excavated at the Hadda site ofTapa-i-ShotorrepresentsBuddhasurrounded by perfectly HellenisticHeraklesandTycheholding acornucopia.[7]The only adaptation of the Greek iconography is that Herakles holds the thunderbolt ofVajrapanirather than his usual club.

According toTarzi,Tapa Shotor, with clay sculptures dated to the 2nd century CE, represents the "missing link" between theHellenistic art of Bactria,and the later stucco sculptures found at Hadda, usually dated to the 3rd-4th century CE.[8]The scultptures of Tapa Shortor are also contemporary with many of the early Buddhist sculptures found inGandhara.[8]

-

Attendants to the Buddha, Tapa Shotor (Niche V1)

-

Site of Tapa Shotor, with a protective roof.[11]

Chakhil-i-Ghoundi monastery (2nd-3rd century CE)

[edit]The Chakhil-i-Ghoundi monastery is dated to the 4th-5th century CE. It is built around theChakhil-i-Ghoundi Stupa,a smalllimestonestupa.Most of the remains of the stupa were gathered in 1928 by the archeological mission of FrenchmanJules Barthouxof theFrench Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan,and have been preserved and reconstituted through a collaboration with theTokyo National Museum.They are today on display at theMusée GuimetinParis.It is usually dated to the 2nd-3rd century CE.

The decoration of the stupa provides an interesting case ofGreco-Buddhistart, combiningHellenisticandIndianartistic elements. The reconstitution consists of several parts, the decorated stupa base, the canopy, and various decorative elements.

-

Canopy of the stupa

-

Scene of "The Gift of Dirt", Chakhil-i-Ghoundi Stupa,Gandhara.

-

Wine and dance scene, with people in Hellenistic clothing

Tapa Kalan monastery (4th-5th century CE)

[edit]

TheTapa Kalanmonastery is dated to the 4th-5th century CE. It was excavated byJules Barthoux.[12]

One of its most famous artifact is an attendant to the Buddha who display manifest Hellenistic styles, the "Genie au Fleur", today in Paris at theGuimet Museum.[13]

-

Buddha statue in Tapa Kalan, Hadda

-

Small stupa decorated with Buddhas, Tapa Kalan, 4th-5th century CE

-

Indo-Corinthian capital,with figure of the Buddha insideacanthusleaves. Tapa Kalan.

-

Buddha with flyingErotesholding a wreath overhead, Tapa Kalan, 3rd century CE

-

Heads, Tapa Kalan.[14]

-

The Great Departure

Bagh-Gai monastery (3rd-4th century CE)

[edit]TheBagh-Gai monasteryis generally dated to the 3rd-4th century CE.[15]Bagh-Gai has many small stupas with decorated niches.[16]

-

Hadda number 13, Bagh Gai monastery, by Charles Masson, 1842.

-

Sculpture from Bagh-Gai

-

Decorative panel, Bagh-Gai monastery

Tapa-i Kafariha Monastery (3rd-4th century CE)

[edit]

TheTapa-i Kafariha Monasteryis generally dated to the 3rd-4th century CE. It was excavated in 1926–27 by an expedition led byJules Barthouxas part of the French Archaeological Delegation to Afghanistan.

-

Hadda number 9, Tepe Kafariha, by Charles Masson, 1842.

-

Niche with the seated Boddhisatva Shakyamuni,Tapa-i Kafariha.Metropolitan Museum of Art.[17]

-

Door casing: Life of the Buddha.Musée Guimet

-

Atlas, on the base of a stupa, Tapa-i Kafariha.[18]

Tapa Tope Kalān monastery (5th century CE)

[edit]This large stupa is about 200 meters to the northeast of the modern city of Hadda. Masson called it "Tope Kalān" (Hadda 10), Barthoux "Borj-i Kafarihā", and it is now designated as "Tapa Tope Kalān".[19]

The stupa at Tope Kalan contained deposits of over 200 mainly silver coins, dating to the 4th-5th century CE. The coins included Sasanian issues ofVarhran IV(388–399 CE),Yazdagird II(438–457 CE) andPeroz I(457/9–84 CE). There were also five Roman goldsolidi:Theodosius II(408–50 CE),Marcianus(450–457 CE) andLeo I(457–474 CE). Many coins were also Hunnic imitations of Sasanian coins with the addition of theAlkhontamgha,and 14Alkhoncoins with rulers showing of their characteristic elongated skulls. All these coins point to a mid-late 5th century date for the stupa.[20]

-

Ruins of the stupa (Hadda 10)

-

Alchon Hun,Sassanian andKidaritecoins from Tapa Kalan (Hadda 10)

-

Small decorative stupa at Hadda 10

Gallery

[edit]-

Polychrome Buddha, 2nd century CE, Hadda.

-

"Laughing boy" from Hadda.

-

Man with helmet, Tapa Kalan, Hadda, 3rd-4th century CE

-

Hadda Buddha fragment, 3rd-4th century CE

-

Hadda statue, 3-4th century CE

-

Head of Buddha, probably from Hadda, ca. 5th–6th century.Metropolitan Museum of Art.[21]

References

[edit]- ^Simpson, William (1881)."Art. VII.—On the Identification of Nagarahara, with reference to the Travels of Hiouen-Thsang".Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society.13(2): 183–207.doi:10.1017/S0035869X00017792.ISSN2051-2066.S2CID163368506.

- ^John Boardman,The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity(ISBN0-691-03680-2)

- ^Vanleene, Alexandra."The Geography of Gandhara Art"(PDF):143.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^Vanleene, Alexandra."The Geography of Gandhara Art"(PDF):158.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^"Following discoveries atAi-Khanum,excavations at Tapa Shotor, Hadda, produced evidence to indicate that Gandharan art descended directly from Hellenised Bactrian art. It is quite clear from the clay figure finds in particular, that either Bactrian artist from the north were placed at the service of Buddhism, or local artists, fully conversant with the style and traditions of Hellenistic art, were the creators of these art objects "inAllchin, Frank Raymond (1997).Gandharan Art in Context: East-west Exchanges at the Crossroads of Asia.Published for the Ancient India and Iran Trust, Cambridge by Regency Publications. p. 19.ISBN9788186030486.

- ^Vanleene, Alexandra."Tapa-e Shotor".Hadda Archeo Data Base.ArcheoDB, 2021.

- ^See imageArchived2012-07-31 atarchive.today

- ^abTarzi, Zémaryalai."Le site ruiné de Hadda":62 ff.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007).The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.Metropolitan Museum of Art.ISBN978-1-58839-224-4.

- ^Boardman, George.The Greeks in Asia.pp. Greeks and their arts in India.

- ^Tarzi, Zémaryalai."Le site ruiné de Hadda".

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^Vanleene, Alexandra."Tapa Tope Kalān".Hadda Archeo DB.

- ^See imageArchived2013-01-03 atarchive.today

- ^"Photograph".RMN.

- ^Barthoux, J. (1928)."BAGH-GAI".Revue des arts asiatiques.5(2): 77–81.ISSN0995-7510.JSTOR43474661.

- ^Rhie, Marylin M. (14 June 2010).Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, Volume 3: The Western Ch'in in Kansu in the Sixteen Kingdoms Period and Inter-relationships with the Buddhist Art of Gandh?ra.BRILL. pp. Fig. 8.32 a to d.ISBN978-90-04-18400-8.

- ^Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007).The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 87.ISBN978-1-58839-224-4.

- ^"Photograph".RMN.

- ^Vanleene, Alexandra."Tapa Tope Kalān".Hadda Archeo DB.

- ^Errington, Elizabeth (2017).Charles Masson and the Buddhist Sites of Afghanistan: Explorations, Excavations, Collections 1832–1835.British Museum. p. 34.doi:10.5281/zenodo.3355036.

- ^"Head of Buddha, Afghanistan (probably Hadda), 5th–6th century".Metropolitan Museum of Artwebsite.

![Head of a Buddha or Bodhisattva, facing (4th-5th century), probably Hadda, Tapa Shotor.[9][10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Head_of_a_Buddha_or_Bodhisattva%2C_facing_%285th-6th_century%29%2C_probably_Hadda%2C_Tapa_Shotor.jpg/151px-Head_of_a_Buddha_or_Bodhisattva%2C_facing_%285th-6th_century%29%2C_probably_Hadda%2C_Tapa_Shotor.jpg)

![Site of Tapa Shotor, with a protective roof.[11]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Wykopaliska_buddyjskie_-_Hadda_-_001545s.jpg/200px-Wykopaliska_buddyjskie_-_Hadda_-_001545s.jpg)

![Heads, Tapa Kalan.[14]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/HaddaTypes.JPG/200px-HaddaTypes.JPG)

![Niche with the seated Boddhisatva Shakyamuni, Tapa-i Kafariha. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[17]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/MET_DP123393.jpg/200px-MET_DP123393.jpg)

![Atlas, on the base of a stupa, Tapa-i Kafariha.[18]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/62/GandharanAtlas.JPG/200px-GandharanAtlas.JPG)

![Head of Buddha, probably from Hadda, ca. 5th–6th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[21]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/64/MET_DP264118_%28cropped%29.jpg/98px-MET_DP264118_%28cropped%29.jpg)