Hagiography

Ahagiography(/ˌhæɡiˈɒɡrəfi/;fromAncient Greekἅγιος,hagios'holy', and-γραφία,-graphia'writing')[1]is abiographyof asaintor anecclesiasticalleader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions.[2][3][4]Early Christian hagiographies might consist of a biography orvita,a description of the saint's deeds or miracles (from Latinvita,life, which begins the title of most medieval biographies), an account of the saint's martyrdom (called apassio), or be a combination of these.

Christian hagiographies focus on the lives, and notably themiracles,ascribed to men and womencanonizedby theRoman Catholic church,theEastern Orthodox Church,theOriental Orthodox churches,and theChurch of the East.Other religious traditions such asBuddhism,[5]Hinduism,[6]Taoism,[7]Islam,SikhismandJainismalso create and maintain hagiographical texts (such as the SikhJanamsakhis) concerning saints, gurus and other individuals believed to be imbued with sacred power.

Hagiographic works, especially those of theMiddle Ages,can incorporate a record of institutional andlocal history,and evidence of popularcults,customs, andtraditions.[8]

However, when referring to modern, non-ecclesiastical works, the termhagiographyis often used today as apejorativereference tobiographiesandhistorieswhose authors are perceived to be uncritical or excessively reverential toward their subject.

Christianity[edit]

Development[edit]

Hagiography constituted an importantliterary genrein theearly Christian church,providing some informational history along with the more inspirational stories andlegends.A hagiographic account of an individual saint could consist of a biography (vita), a description of the saint's deeds or miracles, an account of the saint's martyrdom (passio), or be a combination of these.

The genre of lives of the saints first came into being in theRoman Empireas legends aboutChristianmartyrswere recorded. The dates of their deaths formed the basis ofmartyrologies.In the 4th century, there were three main types of catalogs of lives of the saints:

- annual calendar catalogue, ormenaion(inGreek,μηναῖον,menaionmeans "monthly" (adj,neut), lit. "lunar" ), biographies of the saints to be read atsermons;

- synaxarion( "something that collects"; Greekσυναξάριον,fromσύναξις,synaxisi.e. "gathering", "collection", "compilation" ), or a short version of lives of the saints, arranged by dates;

- paterikon( "that of the Fathers"; Greekπατερικόν;in Greek and Latin,patermeans "father" ), or biography of the specific saints, chosen by the catalog compiler.

The earliest lives of saints focused ondesert fatherswho lived as ascetics from the 4th century onwards. The life ofAnthony of Egyptis usually considered the first example of this new genre of Christian biography.[9]

InWestern Europe,hagiography was one of the more important vehicles for the study of inspirational history during theMiddle Ages.TheGolden LegendofJacobus de Voraginecompiled a great deal of medieval hagiographic material, with a strong emphasis on miracle tales. Lives were often written to promote the cult of local or national states, and in particular to develop pilgrimages to visitrelics.The bronzeGniezno DoorsofGniezno Cathedralin Poland are the onlyRomanesquedoors in Europe to feature the life of a saint. The life of SaintAdalbert of Prague,who is buried in the cathedral, is shown in 18 scenes, probably based on a lost illuminated copy of one of his Lives.

TheBollandistSociety continues the study, academic assembly, appraisal and publication of materials relating to the lives of Christian saints (SeeActa Sanctorum).

Medieval England[edit]

Many of the important hagiographical texts composed in medieval England were written in the vernacular dialectAnglo-Norman.With the introduction ofLatinliterature into England in the 7th and 8th centuries the genre of the life of the saint grew increasingly popular. When one contrasts it to the popular heroic poem, such asBeowulf,one finds that they share certain common features. InBeowulf,the titular character battles againstGrendelandhis mother,while the saint, such asAthanasius'Anthony(one of the original sources for the hagiographic motif) or the character ofGuthlac,battles against figures no less substantial in a spiritual sense. Both genres then focus on the hero-warrior figure, but with the distinction that the saint is of a spiritual sort.

Imitation of the life of Christ was then the benchmark against which saints were measured, and imitation of the lives of saints was the benchmark against which the general population measured itself. InAnglo-SaxonandmedievalEngland, hagiography became a literary genre par excellence for the teaching of a largely illiterate audience. Hagiography provided priests and theologians with classical handbooks in a form that allowed them the rhetorical tools necessary to present their faith through the example of the saints' lives.

Of all the English hagiographers no one was more prolific nor so aware of the importance of the genre as AbbotÆlfric of Eynsham.His workLives of the Saints[10]contains set of sermons on saints' days, formerly observed by the English Church. The text comprises two prefaces, one in Latin and one inOld English,and 39 lives beginning on 25 December with the nativity ofChristand ending with three texts to which no saints' days are attached. The text spans the entire year and describes the lives of many saints, both English and continental, and harks back to some of the earliest saints of the early church.

There are two known instances where saint's lives were adapted into vernacularplaysin Britain. These are theCornish-languageworksBeunans MeriasekandBeunans Ke,about the lives of SaintsMeriasekandKea,respectively.[11]

Other examples of hagiographies from England include:

- theChroniclebyHugh Candidus[12]

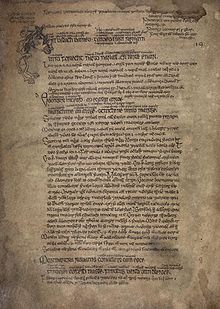

- theSecgan Manuscript[13][14]

- the list ofJohn Leyland[15][16]

- possibly the bookLifebySaintCadog[17]

- Vita Sancti Ricardi Episcopi et Confessoris Cycestrensis/ Life ofRichard of ChichesterbyRalph Bocking.[18]

- TheBook of Margery Kempeis an example of autohagiography, in which the subject dictates her life using the hagiographic form.

Medieval Ireland[edit]

Ireland is notable in its rich hagiographical tradition, and for the large amount of material which was produced during the Middle Ages. Irish hagiographers wrote primarily in Latin while some of the later saint's lives were written in the hagiographer's native vernacularIrish.Of particular note are the lives ofSt. Patrick,St. Columba (Latin)/Colum Cille (Irish)andSt. Brigit/Brigid—Ireland's three patron saints. The earliest extant Life was written byCogitosus.Additionally, several Irish calendars relating to thefeastdaysofChristian saints(sometimes calledmartyrologiesorfeastologies) contained abbreviated synopses of saint's lives, which were compiled from many different sources. Notable examples include theMartyrology of Tallaghtand theFélire Óengusso.Such hagiographical calendars were important in establishing lists of native Irish saints, in imitation of continental calendars.

Eastern Orthodoxy[edit]

In the 10th century, aByzantinemonkSimeon Metaphrasteswas the first one to change the genre of lives of the saints into something different, giving it a moralizing andpanegyricalcharacter. His catalog of lives of the saints became the standard for all of theWesternandEasternhagiographers, who would create relative biographies and images of the ideal saints by gradually departing from the real facts of their lives. Over the years, the genre of lives of the saints had absorbed a number of narrative plots and poetic images (often, of pre-Christian origin, such asdragonfighting etc.), mediaevalparables,short stories andanecdotes.

The genre of lives of the saints was introduced in the Slavic world in theBulgarian Empirein the late 9th and early 10th century, where the first original hagiographies were produced onCyril and Methodius,Clement of OhridandNaum of Preslav.Eventually the Bulgarians brought this genre toKievan Rus'together withwritingand also intranslationsfrom the Greek language. In the 11th century, they began to compile the original life stories of their first saints, e.g.Boris and Gleb,Theodosius Pecherskyetc. In the 16th century,Metropolitan Macariusexpanded the list of the Russian saints and supervised the compiling process of their life stories. They would all be compiled in the so-calledVelikiye chet'yi-mineicatalog (Великие Четьи-Минеи, orGreat Menaion Reader), consisting of 12volumesin accordance with each month of the year. They were revised and expanded by St.Dimitry of Rostovin 1684–1705.

TheLife of Alexander Nevskywas a particularly notable hagiographic work of the era.

Today, the works in the genre of lives of the saints represent a valuable historical source and reflection of different social ideas, world outlook andaestheticconceptsof the past.

Oriental Orthodoxy[edit]

TheOriental Orthodox Churchesalso have their own hagiographic traditions. For instance,Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Churchhagiographies in theGe'ez languageare known asgadl(Saint's Life).[19]There are some 200 hagiographies about indigenous saints.[20]They are among the most importantMedieval Ethiopianwritten sources, and some have accurate historical information.[21]They are written by the disciples of the saints. Some were written a long time after the death of a saint, but others were written not long after the saint's demise.[22][23]Fragments from an Old Nubian hagiography of Saint Michael are extant.[24]

Judaism[edit]

Jewish hagiographic writings are common in the case of Talmudic and Kabbalistic writings and later in theHasidicmovement.[25]

Islam[edit]

Hagiography in Islam began in theArabic languagewith biographical writing about the ProphetMuhammadin the 8th century CE, a tradition known assīra.From about the 10th century CE, a genre generally known asmanāqibalso emerged, which comprised biographies of theimams(madhāhib) who founded different schools of Islamic thought (madhhab) aboutshariʿa,and ofṢūfī saints.Over time, hagiography about Ṣūfīs and their miracles came to predominate in the genre ofmanāqib.[26]

Likewise influenced by early Islamicresearch into hadithsand other biographical information about the Prophet, Persian scholars began writingPersian hagiography,again mainly of Sūfī saints, in the eleventh century CE.

The Islamicisation of the Turkish regions led to the development ofTurkishbiographies of saints, beginning in the 13th century CE and gaining pace around the 16th. Production remained dynamic and kept pace with scholarly developments in historical biographical writing until 1925, whenMustafa Kemal Atatürk(d. 1938) placed an interdiction on Ṣūfī brotherhoods. As Turkey relaxed legal restrictions on Islamic practice in the 1950s and the 1980s, Ṣūfīs returned to publishing hagiography, a trend which continues in the 21st century.[27]

Other groups[edit]

Thepseudobiography of L. Ron Hubbardcompiled by theChurch of Scientologyis commonly described as a heavily fictionalized hagiography.[28][29]

See also[edit]

- Jean Bolland

- Boniface Consiliarius

- Alban Butler

- Danilo's student

- Hippolyte Delehaye

- Namtar (biography)

- Pseudepigrapha

- Reginald of Durham

- Secular saint

References[edit]

- ^"hagiography".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^Rico G. Monge (2016). Rico G. Monge, Kerry P. C. San Chirico and Rachel J. Smith (ed.).Hagiography and Religious Truth: Case Studies in the Abrahamic and Dharmic Traditions.Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 7–22.ISBN978-1474235792.

- ^Jeanette Blonigen Clancy (2019).Beyond Parochial Faith: A Catholic Confesses.Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 137.ISBN978-1532672828.

- ^Rapp, Claudia (2012). "Hagiography and the Cult of Saints in the Light of Epigraphy and Acclamations".Byzantine Religious Culture.Brill Academic. pp. 289–311.doi:10.1163/9789004226494_017.ISBN978-9004226494.

- ^Jonathan Augustine (2012),Buddhist Hagiography in Early Japan,Routledge,ISBN978-0415646291

- ^David Lorenzen(2006),Who Invented Hinduism?,Yoda Press,ISBN978-8190227261,pp. 120–121

- ^Robert Ford Campany (2002),To Live as Long as Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents,University of California Press,ISBN978-0520230347

- ^Davies, S. (2008).Archive and manuscripts: contents and use: using the sources(3rd ed.). Aberystwyth, UK: Department of Information Studies, Aberystwyth University. p. 5.20.ISBN978-1906214159

- ^Talbot, Alice-Mary (21 November 2012)."Hagiography".academic.oup.com.doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199252466.013.0082.Retrieved21 April2024.

- ^Ælfric of Eynsham.The Lives of the Saints.Retrieved1 December2018.

- ^Koch, John T. (2006).Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO. pp. 203–205.ISBN1851094407.Retrieved23 November2009.

- ^Barbara Yorke,Nunneries and theAnglo-SaxonRoyal Houses(Continuum, 2003)p. 22

- ^Stowe MS 944Archived3 January 2014 atarchive.today,British Library

- ^G. Hickes,Dissertatio Epistolaris in Linguarum veterum septentrionalium thesaurus grammatico-criticus et archeologicus(Oxford 1703–05), p. 115.

- ^John Leland,TheCollectanea of British affairs,Volume 2.p. 408.

- ^Liuzza, R. M. (2006)."The Year's Work in Old English Studies"(PDF).Old English News Letter.39(2). Medieval Institute, Western Michigan University: 8.

- ^Tatlock, J. S. P. (1939). "The Dates of the Arthurian Saints' Legends".Speculum.14(3): 345–365.doi:10.2307/2848601.JSTOR2848601.S2CID163470282.p. 345

- ^Jones, David, ed. (1995).Saint Richard of Chichester: the sources for his life.Lewes: Sussex Record Society. p. 8.ISBN0854450408.

- ^Kelly, Samantha (2020).A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea.Brill.ISBN978-9004419582.

- ^Kefyalew Merahi. Saints and Monasteries in Ethiopia. 2 vols. Vol. 2, Addis Ababa: Commercial Printing Press, 2003.

- ^Tamrat, Taddesse (1970).Hagiographies and the Reconstruction of Medieval Ethiopian History.

- ^"Lives of Ethiopian Saints".Link Ethiopia.Archived fromthe originalon 5 March 2017.Retrieved4 March2017.

- ^Galawdewos (2015).The Life and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros: A Seventeenth-Century African Biography of an Ethiopian Woman.Princeton University Press.ISBN978-0691164212.

- ^van Gerven Oei, Vincent W. J.; Laisney, Vincent Pierre-Michel; Ruffini, Giovanni; Tsakos, Alexandros; Weber-Thum, Kerstin; Weschenfelder, Petra (2016).The Old Nubian Texts from Attiri.punctum books.doi:10.21983/P3.0156.1.00.

- ^"Hagiography",Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^Ch. Pellat, "Manāḳib", inEncyclopaedia of Islam,ed. by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, and W.P. Heinrichs, 2nd edn, 12 vols (Leiden: Brill, 1960–2005),doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0660.

- ^Alexandre Papas, "Hagiography, Persian and Turkish", inEncyclopaedia of Islam, Three,ed. by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson (Leiden: Brill, 2007–),doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23914.

- ^Tucker, Ruth A. (1989).Another Gospel: Cults, Alternative Religions, and the New Age Movement.Zondervan.ISBN0310259371.OL9824980M.

- ^Lewis, James R.; Hammer, Olav (2007).The Invention of Sacred Tradition.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-86479-4.Retrieved8 August2016.

Further reading[edit]

- DeWeese, Devin.Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tukles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition.State College, PA: Penn State University Press, 2007.

- Eden, Jeff.Warrior Saints of the Silk Road: Legends of the Qarakhanids.Brill: Leiden, 2018.

- Heffernan, Thomas J.Sacred Biography: Saints and Their Biographers in the Middle Ages.Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2019). "Serbian hagiographies on the warfare and political struggles of the Nemanjić dynasty (from the twelfth to the fourteenth century)".Reform and Renewal in Medieval East and Central Europe: Politics, Law and Society.Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 103–129.

- Mariković, Ana and Vedriš, Trpimir eds.Identity and alterity in Hagiography and the Cult of Saints(Bibliotheca Hagiotheca, Series Colloquia 1). Zagreb: Hagiotheca, 2010.

- Renard, John.Friends of God: Islamic Images of Piety, Commitment, and Servanthood.Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

- Vauchez, André,La sainteté en Occident aux derniers siècles du Moyen Âge (1198–1431)(BEFAR,241). Rome, 1981. [Engl. transl.:Sainthood in the Later Middle Ages.Cambridge, 1987; Ital. transl.:La santità nel Medioevo.Bologna, 1989].

External links[edit]

- Hippolyte Delehaye,The Legends of the Saints: An Introduction to Hagiography(1907)

- Delehaye, Hippolyte(1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 12 (11th ed.). pp. 816–817.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913)..Catholic Encyclopedia.New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- James Kiefer's Hagiographies

- Societé des BollandistesArchived29 May 2011 at theWayback Machine

- Hagiography Society