Hanja

| Hanja | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Logographic

|

Time period | 400 BCE – present |

| Languages | Korean,Classical Chinese |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Kanji,traditional Chinese,simplified Chinese,Khitan script,Chữ Hán,Chữ Nôm,Jurchen script,Tangut script |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hani(500),Han (Hanzi, Kanji, Hanja) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Han |

| Hanja | |

| Hangul | 한자 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | Hán tự |

| Revised Romanization | Hanja |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hancha |

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

|

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

| Transliteration |

Hanja(Korean:한자;Hanja:Hán tự,Korean pronunciation:[ha(ː)ntɕ͈a]), alternatively known asHancha,areChinese charactersused to write theKorean language.After characters were introduced to Korea to writeLiterary Chinese,they were adapted to write Korean as early as theGojoseonperiod.

Hanja-eo(한자어,Hán tựNgữ) refers toSino-Korean vocabulary,which can be written with Hanja, andhanmun(한문,Hán văn) refers toClassical Chinesewriting, althoughHanjais also sometimes used to encompass both concepts. Because Hanja characters have never undergone any major reforms, they more closely resembletraditional Japanese(구자체,Cựu tự thể) andtraditional Chinese characters,although thestroke ordersfor certain characters are slightly different. Such examples are the charactersGiáoandGiáo,as well asNghiênandNghiên.[1]Only a small number of Hanja characters were modified or are unique to Korean, with the rest being identical to thetraditional Chinese characters.By contrast, many of the Chinese characters currently in use inmainland China,MalaysiaandSingaporehave beensimplified,and contain fewer strokes than the corresponding Hanja characters.

Until the contemporary period, Korean documents, history, literature and records were written primarily inLiterary Chineseusing Hanja as its primary script. As early as 1446,Sejong the GreatpromulgatedHangul(also known as Chosŏn'gŭl inNorth Korea) through theHunminjeongeum.It did not come into widespread official use until the late 19th and early 20th century.[2][3]Proficiency in Chinese characters is, therefore, necessary to study Korean history.Etymologyof Sino-Korean words are reflected in Hanja.[4]

Hanja were once used to write native Korean words, in a variety of systems collectively known asidu,but by the 20th century Koreans used hanja only for writing Sino-Korean words, while writing native vocabulary andloanwordsfrom other languages in Hangul. By the 21st century, even Sino-Korean words are usually written in the Hangul alphabet, with the corresponding Chinese character sometimes written next to it to prevent confusion if there are other characters or words with the same Hangul spelling. According to theStandard Korean Language Dictionarypublished by theNational Institute of Korean Language(NIKL), approximately half (50%) of Korean words are Sino-Korean, mostly in academic fields (science, government, and society).[5]Other dictionaries, such as theUrimal Keun Sajeon,claim this number might be as low as roughly 30%.[6][7]

History

[edit]Introduction of literary Chinese to Korea

[edit]

There is traditionally no accepted date for whenliterary Chinese(한문;Hán văn;hanmun) written inChinese characters(한자;Hán tự;hanja) entered Korea. Early Chinese dynastic histories, the only sources for very early Korea, do not mention a Korean writing system. During the 3rd century BC, Chinese migrations into the peninsula occurred due to war in northern China and the earliest archaeological evidence of Chinese writing appearing in Korea is dated to this period. A large number of inscribedknife moneyfrom pre-Lelangsites along theYalu Riverhave been found. A sword dated to 222 BC with Chinese engraving was unearthed inPyongyang.[8]

From 108 BC to 313 AD, theHan dynastyestablished theFour Commanderies of Hanin northern Korea and institutionalized the Chinese language.[9]According to theSamguk Sagi,Goguryeohadhanmunfrom the beginning of its existence, which starts in 37 BC.[10]It also says that the king of Goguryeo composed a poem in 17 BC. TheGwanggaeto Stele,dated to 414, is the earliest securely dated relic bearinghanmuninscriptions.Hanmunbecame commonplace in Goguryeo during the 5th and 6th centuries and according to theBook of Zhou,the Chinese classics were available in Goguryeo by the end of the 6th century. TheSamguk Sagimentions written records inBaekjebeginning in 375 and Goguryeo annals prior to 600.[11]Japanese chronicles mention Baekje people as teachers ofhanmun.According to theBook of Liang,the people ofSilladid not have writing in the first half of the 6th century but this may have been only referring to agreements and contracts, represented by notches on wood. TheBei Shi,covering the period 386–618, says that the writing, armour, and weapons in Silla were the same as those in China. TheSamguk Sagisays that records were kept in Silla starting in 545.[12]

Some western writers claimed that knowledge of Chinese entered Korea withthe spread of Buddhism,which occurred around the 4th century.[9]Traditionally Buddhism is believed to have been introduced to Goguryeo in 372, Baekje in 384, and Silla in 527.[13]

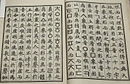

Another major factor in the adoption ofhanmunwas the adoption of thegwageo,copied from the Chineseimperial examination,open to all freeborn men. Special schools were set up for the well-to-do and the nobility across Korea to train new scholar officials for civil service. Adopted by Silla and Goryeo, thegwageosystem was maintained by Goryeo until after the unification of Korea at the end of the nineteenth century. The scholarly élite began learning thehanjaby memorising theThousand Character Classic(천자문;Thiên tự văn;Cheonjamun),Three Character Classic(삼자경;Tam tự kinh;Samja Gyeong) andHundred Family Surnames(백가성;Bách gia tính;Baekga Seong). Passage of thegwageorequired the thorough ability to read, interpret and compose passages of works such as theAnalects(논어;Luận ngữ;Non-eo),Great Learning(대학;Đại học;Daehak),Doctrine of the Mean(중용;Trung dung;Jung-yong),Mencius(맹자;Mạnh tử;Maengja),Classic of Poetry(시경;Thi kinh;Sigyeong),Book of Documents(서경;Thư kinh;Seogyeong),Classic of Changes(역경;Dịch kinh;Yeokgyeong),Spring and Autumn Annals(춘추;Xuân thu;Chunchu) andBook of Rites(예기;Lễ ký;Yegi). Other important works includeSūnzǐ's Art of War(손자병법;Tôn tử binh pháp;Sonja Byeongbeop) andSelections of Refined Literature(문선;Văn tuyển;Munseon).

The Korean scholars were very proficient in literary Chinese. The craftsmen and scholars ofBaekjewere renowned in Japan, and were eagerly sought as teachers due to their proficiency inhanmun.Korean scholars also composed all diplomatic records, government records, scientific writings, religious literature and much poetry inhanmun,demonstrating that the Korean scholars were not just reading Chinese works but were actively composing their own. Well-known examples ofChinese-language literature in KoreaincludeThree Kingdoms History(삼국사기;Tam quốc sử ký;Samguk Sagi),Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms(삼국유사;Tam quốc di sự;Samguk Yusa),New Stories of the Golden Turtle(금오신화;Kim ngao tân thoại;Geumo Sinhwa),The Cloud Dream of the Nine(구운몽;Cửu vân mộng;Gu Unmong),Musical Canon(악학궤범;Nhạc học quỹ phạm;Akhak Gwebeom),The Story of Hong Gildong(홍길동전;Hồng cát đồng truyện;Hong Gildong Jeon) andLicking One's Lips at the Butcher's Door(도문대작;Đồ môn đại tước;Domun Daejak).

Adaptation ofhanjato Korean

[edit]The Chinese language, however, was quite different from the Korean language, consisting of terse, often monosyllabic words with a strictly analytic, SVO structure in stark contrast to the generally polysyllabic, very synthetic, SOV structure, with various grammatical endings that encoded person, levels of politeness and case found in Korean. Despite the adoption of literary Chinese as the written language, Chinese never replaced Korean as the spoken language, even amongst the scholars that had immersed themselves into its study.

The first attempts to make literary Chinese texts more accessible to Korean readers werehanmunpassages written in Korean word order. This would later develop into thegugyeol(구결;Khẩu quyết) or 'separated phrases,' system. Chinese texts were broken into meaningful blocks, and in the spaces were insertedhanjaused to represent the sound of native Korean grammatical endings. As literary Chinese was very terse, leaving much to be understood from context, insertion of occasional verbs and grammatical markers helped to clarify the meaning. For instance, thehanja'Vi' was used for its native Korean gloss whereas 'Ni' was used for its Sino-Korean pronunciation, and combined into 'Vi ni' and readhani(하니), 'to do (and so).'[14]In Chinese, however, the same characters are read in Mandarin as the expressionwéi ní,meaning 'becoming a nun'. This is a typical example of Gugyeol words where the radical (Vi) is read in Korean for its meaning (hă—'to do'), whereas the suffixNi,ni(meaning 'nun'), is used phonetical. Special symbols were sometimes used to aid in the reordering of words in approximation of Korean grammar. It was similar to thekanbun(Hán văn) system developed in Japan to render Chinese texts. The system was not a translation of Chinese into Korean, but an attempt to make Korean speakers knowledgeable inhanjaovercome the difficulties in interpreting Chinese texts. Although it was developed by scholars of the earlyGoryeoKingdom (918–1392),gugyeolwas of particular importance during the Joseon period, extending into the first decade of the twentieth century, since all civil servants were required to be able to read, translate and interpret Confucian texts and commentaries.[15]

The first attempt at transcribing Korean inhanjawas theidu(이두;Lại độc), or 'official reading,' system that began to appear after 500 AD. In this system, thehanjawere chosen for their equivalent native Korean gloss. For example, thehanja'Bất đông' signifies 'no winter' or 'not winter' and has the formal Sino-Korean pronunciation of (부동)budong,similar toMandarinbù dōng.Instead, it was read asandeul(안들) which is the Middle Korean pronunciation of the characters' native gloss and is ancestor to modernanneunda(않는다), 'do not' or 'does not.' The variousiduconventions were developed in the Goryeo period but were particularly associated with thejung-in(중인;Trung nhân), the uppermiddle classof the early Joseon period.[16]

A subset ofiduwas known ashyangchal(향찰;Hương trát), 'village notes,' and was a form ofiduparticularly associated with thehyangga(향가;Hương ca) the old poetry compilations and some new creations preserved in the first half of the Goryeo period when its popularity began to wane.[9]In thehyangchalor 'village letters' system, there was free choice in how a particularhanjawas used. For example, to indicate the topic of Princess Seonhwa, a daughter of KingJinpyeong of Sillawas recorded as 'Thiện hóa công chủ chủ ẩn' inhyangchaland was read as (선화공주님은),seonhwa gongju-nim-eunwhere 'Thiện hóa công chủ' is read in Sino-Korean, as it is a Sino-Korean name and the Sino-Korean term for 'princess' was already adopted as a loan word. Thehanja'Chủ ẩn,' however, were read according to their native pronunciation but was not used for its literal meaning signifying 'the prince steals' but to the native postpositions (님)nim,the honorific marker used after professions and titles, andeun,the topic marker. Inmixed script,this would be rendered as 'Thiện hóa công chủ 님은'.[16][15]

Hanja were the sole means of writing Korean until KingSejong the Greatinvented and tried promotingHangulin the 15th century. Even after the invention of Hangul, however, most Korean scholars continued to write inhanmun,although Hangul did see considerable popular use.Iduand itshyangchalvariant were mostly replaced by mixed-script writing withhangulalthoughiduwas not officially discontinued until 1894 when reforms abolished its usage in administrative records of civil servants. Even withidu,most literature and official records were still recorded in literary Chinese until 1910.[16][15]

Decline of Hanja

[edit]TheHangul-Hanja mixed scriptwas a commonly used means of writing, and Hangul effectively replaced Hanja in official and scholarly writing only in the 20th century. Hangŭl exclusive writing has been used concurrently in Korea after the decline of literary Chinese. Mixed script could be commonly found in non-fiction writing, news papers, etc., until the enacting ofPark Chung Hee's 5 Year Plan for Hangŭl Exclusivity[17]hangŭl jŏnyong ogaenyŏn gyehuik an(Korean:한글전용 5개년 계획안;Hanja:한글 chuyên dụng 5 cá niên kế hoa án) in 1968 banned the use and teaching of Hanja in public schools, as well as forbade its use in the military, with the goal of eliminating Hanja in writing by 1972 through legislative and executive means. However, due to public backlash, in 1972, Park's government allowed for the teaching of Hanja in special classes but maintained a ban on Hanja use in textbooks and other learning materials outside of the classes. This reverse step, however, was optional so the availability of Hanja education was dependent on the school one went to. Park's Hanja ban was not formally lifted until 1992 under the government ofKim Young-sam.In 1999, the government ofKim Dae-jungactively promoted Hanja by placing it on signs on the road, at bus stops, and in subways. In 1999, Han Mun was reintroduced as a school elective and in 2001 the Hanja Proficiency Testhanja nŭngryŏk gŏmjŏng sihŏm(Korean:한자능력검정시험;Hanja:Hán tự năng lực kiểm định thí nghiệm) was introduced. In 2005, an older law, the Law Concerning Hangul Exclusivityhangŭl jŏnyonge gwahak pŏmnyul(Korean:한글전용에 관한 법률;Hanja:한글 chuyên dụng 에 quan 한 pháp luật) was repealed as well. In 2013 all elementary schools in Seoul started teaching Hanja. However, the result is that Koreans who were educated in this period having never been formally educated in Hanja are unable to use them, and thus the use of Hanja has plummeted in orthography until the modern day. Where Hanja is now very rarely used and is almost only used for abbreviations in newspaper headlines (e.g.Trungfor China,Hànfor Korea,Mỹfor the United States,Nhậtfor Japan, etc.), for clarification in text where a word might be confused for another due to homophones (e.g.이사장(Lý xã trường) vs.이사장(Lý sự trường)), or for stylistic use such as theTân(Korean:신라면;Hanja:Tân lạp diện) used onShin Ramyŏnpackaging.

Since June 1949, Hanja has not officially been used inNorth Korea,and, in addition, most texts are now commonly written horizontally instead of vertically. Many words borrowed from Chinese have also been replaced in the North with native Korean words, due to the North's policy oflinguistic purism.Nevertheless, a large number of Chinese-borrowed words are still widely used in the North (although written in Hangul), and Hanja still appear in special contexts, such as recent North Koreandictionaries.[18]The replacement has been less total inSouth Koreawhere, although usage has declined over time, some Hanja remain in common usage in some contexts.

Character formation

[edit]Each Hanja is composed of one of 214radicalsplus in most cases one or more additional elements. The vast majority of Hanja use the additional elements to indicate the sound of the character, but a few Hanja are purely pictographic, and some were formed in other ways.

The historical use of Hanja in Korea has had a change over time. Hanja became prominent in use by the elite class between the 3rd and 4th centuries by the Three Kingdoms. The use came from Chinese that migrated into Korea. With them they brought the writing system Hanja. Thus the hanja being used came from the characters already being used by the Chinese at the time.

Since Hanja was primarily used by the elite and scholars, it was hard for others to learn, thus much character development was limited. Scholars in the 4th century used this to study and write Confucian classics. Character formation is also coined to theiduform which was a Buddhist writing system for Chinese characters. This practice however was limited due to the opinion of Buddhism whether it was favorable at the time or not.

Eumhun

[edit]To aid in understanding the meaning of a character, or to describe it orally to distinguish it from other characters with the same pronunciation, character dictionaries and school textbooks refer to each character with a combination of its sound and a word indicating its meaning. This dual meaning-sound reading of a character is calledeumhun(음훈; âm huấn;fromÂm'sound' +Huấn'meaning,' 'teaching').

The word or words used to denote the meaning are often—though hardly always—words of native Korean (i.e., non-Chinese) origin, and are sometimes archaic words no longer commonly used.

Education

[edit]South

[edit]South Korean primary schools ceased the teaching of Hanja in elementary schools in the 1970s, although they are still taught as part of the mandatory curriculum in grade 6. They are taught in separate courses inSouth Korean high schools,separately from the normal Korean-language curriculum. Formal Hanja education begins in grade 7 (junior high school) and continues until graduation from senior high school in grade 12.

A total of 1,800 Hanja are taught: 900 for junior high, and 900 for senior high (starting in grade 10).[19]Post-secondary Hanja education continues in someliberal-artsuniversities.[20]The 1972 promulgation ofbasic Hanja for educational purposeschanged on December 31, 2000, to replace 44 Hanja with 44 others.[21]

South Korea'sMinistry of Educationgenerally encourages all primary schools to offer Hanja classes. Officials said that learning Chinese characters could enhance students' Korean-language proficiency.[22]Initially announced as a mandatory requirement, it is now considered optional.[23]

North

[edit]Though North Korea rapidly abandoned the general use of Hanja soon after independence,[24]the number of Hanja taught in primary and secondary schools is actually greater than the 1,800 taught in South Korea.[25]Kim Il Sunghad earlier called for a gradual elimination of the use of Hanja,[26]but by the 1960s, he had reversed his stance; he was quoted as saying in 1966, "While we should use as few Sinitic terms as possible, students must be exposed to the necessary Chinese characters and taught how to write them."[27]

As a result, a Chinese-character textbook was designed for North Korean schools for use in grades 5–9, teaching 1,500 characters, with another 500 for high school students.[28]College students are exposed to another 1,000, bringing the total to 3,000.[29]

Uses

[edit]Because many different Hanja—and thus, many different words written using Hanja—often share thesame sounds,two distinct Hanja words (Hanjaeo) may be spelled identically in thephoneticHangulalphabet.Hanja's language of origin, Chinese, has many homophones, and Hanja words became even more homophonic when they came into Korean, since Korean lacks atonal system,which is how Chinese distinguishes many words that would otherwise be homophonic. For example, whileĐạo,Đao,andĐảoare all phonetically distinct in Mandarin (pronounceddào,dāo,anddǎorespectively), they are all pronounceddo(도) in Korean. For this reason, Hanja are often used to clarify meaning, either on their own without the equivalent Hangul spelling or in parentheses after the Hangul spelling as a kind of gloss. Hanja are often also used as a form of shorthand in newspaper headlines, advertisements, and on signs, for example the banner at the funeral for thesailorslost in the sinking ofROKS Cheonan (PCC-772).[30]

Print media

[edit]

In South Korea, Hanja are used most frequently in ancient literature, legal documents, and scholarly monographs, where they often appear without the equivalent Hangul spelling. Usually, only those words with a specialized or ambiguous meaning are printed in Hanja. In mass-circulation books and magazines, Hanja are generally used rarely, and only to gloss words already spelled in Hangul when the meaning is ambiguous. Hanja are also often used in newspaper headlines as abbreviations or to eliminate ambiguity.[31]

In formal publications, personal names are also usually glossed in Hanja in parentheses next to the Hangul. Aside from academic usage, Hanja are often used for advertising or decorative purposes in South Korea, and appear frequently in athletic events and cultural parades, packaging and labeling, dictionaries andatlases.For example, the HanjaTân(sinorshin,meaning 'spicy') appears prominently on packages ofShin Ramyunnoodles.[32]In contrast, North Korea eliminated the use of Hanja even in academic publications by 1949 on the orders ofKim Il Sung,a situation that has since remained unchanged.[27]

Dictionaries

[edit]In modern Korean dictionaries, all entry words of Sino-Korean origin are printed in Hangul and listed in Hangul order, with the Hanja given in parentheses immediately following the entry word.

This practice helps to eliminate ambiguity, and it also serves as a sort of shorthand etymology, since the meaning of the Hanja and the fact that the word is composed of Hanja often help to illustrate the word's origin.

As an example of how Hanja can help to clear up ambiguity, many homophones can be distinguished by using hanja. An example is the word수도(sudo), which may have meanings such as:[33]

- Tu đạo:spiritual discipline

- Tù đồ:prisoner

- Thủy đô:'city of water' (e.g.VeniceorSuzhou)

- Thủy đạo:paddy rice

- Thủy đạo:drain, rivers, path of surface water

- Toại đạo:tunnel

- Thủ đô:capital (city)

- Thủ đao:hand knife

Hanja dictionaries for specialist usage –Jajeon(자전, tự điển) orOkpyeon(옥편, ngọc thiên) – are organized byradical(the traditional Chinese method of classifying characters).

Personal names

[edit]Korean personal names,including allKorean surnamesand mostKorean given names,are based on Hanja and are generally written in it, although some exceptions exist.[4]On business cards, the use of Hanja is slowly fading away, with most older people displaying their names exclusively in Hanja while most of the younger generation using both Hangul and Hanja. Korean personal names usually consist of a one-character family name (seong,성, tính) followed by a two-character given name (ireum,이름). There are a few two-character family names (e.g.남궁, nam cung,Namgung), and the holders of such names—but not only them—tend to have one-syllable given names. Traditionally, the given name in turn consists of one character unique to the individual and one character shared by all people in a family of the same sex and generation (seeGeneration name).[4]

During theJapanese administrationof Korea (1910–1945), Koreanswere forced to adopt Japanese-style names,includingpolysyllabic readingsof the Hanja, but this practice was reversed by post-independence governments in Korea. Since the 1970s, some parents have given their childrengiven namesthat are simply native Korean words. Popular ones includeHaneul(하늘)—meaning 'sky'—andIseul(이슬)—meaning 'morning dew'. Nevertheless, on official documents, people's names are still recorded in both Hangul and in Hanja.[4]

Toponymy

[edit]Due to standardization efforts duringGoryeoandJoseoneras, native Koreanplacenameswere converted to Hanja, and most names used today are Hanja-based. The most notable exception is the name of the capital,Seoul,a native Korean word meaning 'capital' with no direct Hanja conversion; the Hanjagyeong(경, kinh,'capital') is sometimes used as a back-rendering. For example, disyllabic names of railway lines, freeways, and provinces are often formed by taking one character from each of the two locales' names; thus,

- TheGyeongbu(경부,Kinh phủ) corridor connects Seoul (gyeong,Kinh) andBusan(bu,Phủ);

- TheGyeongin(경인,Kinh nhân) corridor connects Seoul andIncheon(in,Nhân);

- The formerJeolla(전라,Toàn la) Province took its name from the first characters in the city namesJeonju(전주,Toàn châu) andNaju(나주,La châu) (Najuis originallyRaju,but the initial "r/l" sound in South Korean is simplified to "n" ).

Most atlases of Korea today are published in two versions: one in Hangul (sometimes with some English as well), and one in Hanja. Subway and railway station signs give the station's name in Hangul, Hanja, and English, both to assist visitors (including Chinese or Japanese who may rely on the Hanja spellings) and to disambiguate the name.

Academia

[edit]

Hanja are still required for certain disciplines in academia, such asOriental Studiesand other disciplines studying Chinese, Japanese or historic Korean literature and culture, since the vast majority of primary source text material are written inHanzi,Kanjior Hanja.[34]

Art and culture

[edit]For the traditional creative arts such ascalligraphyandpainting,a knowledge of Hanja is needed to write and understand the various scripts and inscriptions, as is the same in China and Japan. Many old songs and poems are written and based on Hanja characters.

On 9 September 2003, the celebration for the 55th anniversary of North Korea featured a float decorated with the scenario for welcomingKim Il-Sung,which including a banner with Kim Il-Sung's name written in Hanja.[35]

Popular usage

[edit]

Opinion surveys in South Korea regarding the issue of Hanja use have had mixed responses in the past. Hanja terms are also expressed through Hangul, the standard script in the Korean language. Hanja use within general Korean literature has declined since the 1980s because formal Hanja education in South Korea does not begin until the seventh year of schooling, due to changes in government policy during the time.

In 1956, one study found mixed-script Korean text (in whichSino-Koreannouns are written using Hanja, and other words using Hangul) were read faster than texts written purely in Hangul; however, by 1977, the situation had reversed.[36]In 1988, 65% of one sample of people without a college education "evinced no reading comprehension of any but the most common hanja" when reading mixed-script passages.[37]

Gukja

[edit]A small number of characters were invented by the Koreans themselves. These characters are calledgukja(국자, quốc tự,literally 'national characters'). Most of them are for proper names (place-names and people's names) but some refer to Korean-specific concepts and materials. They include畓(답;dap;'paddy field'),欌(장;jang,'wardrobe'),乭(돌;Dol,a character only used in given names),㸴(소;So,a rare surname fromSeongju), and怾(기;Gi,an old name referring toKumgangsan).

Further examples includePhu(부bu),Di(탈tal),䭏(편pyeon),哛(뿐ppun), and椧(명myeong). SeeKorean gukja characters at Wiktionaryfor more examples.

Compare to the parallel development in Japan ofkokuji(Quốc tự),of which there are hundreds, many rarely used. These were often developed for native Japanese plants and animals.

Yakja

[edit]

Some Hanja characters have simplified forms (약자,Lược tự,yakja) that can be seen in casual use. An example is![]() ,which is acursiveform ofVô(meaning 'nothing').

,which is acursiveform ofVô(meaning 'nothing').

Pronunciation

[edit]Each Hanja character is pronounced as a single syllable, corresponding to a single composite character in Hangul. Thepronunciationof Hanja in Korean is by no means identical to the way they are pronounced in modern Chinese, particularlyMandarin,although some Chinese dialects and Korean share similar pronunciations for some characters. For example,Ấn xoát"print" isyìnshuāin Mandarin Chinese andinswae(인쇄) in Korean, but it is pronouncedinsahinShanghainese(aWu Chinesedialect).

One difference is the loss oftonefrom standard Korean while most Chinese dialects retain tone. In other aspects, the pronunciation of Hanja is more conservative than most northern and central Chinese dialects, for example in the retention of labial consonantcodasin characters with labial consonantonsets,such as the charactersPháp(법beop) andPhàm(범beom);labialcodas existed inMiddle Chinesebut do not survive intact in most northern and central Chinese varieties today, and even in many southern Chinese varieties that still retain labial codas, includingCantoneseandHokkien,labial codas in characters with labial onsets are replaced by theirdentalcounterparts.

Due to divergence in pronunciation since the time of borrowing, sometimes the pronunciation of a Hanja and its correspondinghanzimay differ considerably. For example,Nữ('woman') isnǚin Mandarin Chinese andnyeo(녀) in Korean. However, in most modern Koreandialects(especiallySouth Koreanones),Nữis pronounced asyeo(여) when used in an initial position, due to a systematicelisionof initialnwhen followed byyori.Additionally, sometimes a Hanja-derived word will have altered pronunciation of a character to reflect Korean pronunciation shifts, for example,mogwa모과 mộc qua'quince' frommokgwa목과,andmoran모란 mẫu đan'Paeonia suffruticosa' frommokdan목단.

There are some pronunciation correspondence between the onset, rhyme, and coda betweenCantoneseand Korean.[38]

When learning how to write Hanja, students are taught to memorize the native Korean pronunciation for the Hanja's meaning and the Sino-Korean pronunciations (the pronunciation based on the Chinese pronunciation of the characters) for each Hanja respectively so that students know what the syllable and meaning is for a particular Hanja. For example, the name for the HanjaThủyis물 수(mul-su) in which물(mul) is the native Korean pronunciation for 'water', while수(su) is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of the character. The naming of Hanja is similar to ifwater,horseandgoldwere named "water-aqua", "horse-equus", or "gold-aurum" based on a hybridization of both the English and the Latin names. Other examples include사람 인(saram-in) forNhân'person/people',클 대(keul-dae) forĐại'big/large/great',작을 소(jageul-so) forTiểu'small/little',아래 하(arae-ha) forHạ'underneath/below/low',아비 부(abi-bu) forPhụ'father', and나라이름 한(naraireum-han) forHàn'Han/Korea'.

See also

[edit]- Chinese characters

- Chinese influence on Korean culture

- Chinese-language literature of Korea

- East Asian cultural sphere

- Kanji– Chinese characters used for writing Japanese (Japanese equivalent of Hanja)

- McCune–Reischauer

- Korean mixed script

- New Korean Orthography

- Revised Romanization of Korean

- Yale romanization of Korean

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^"Korean Hanja Characters".SayJack.Retrieved4 November2017.

- ^"알고 싶은 한글".National Institute of Korean Language.Retrieved22 March2018.

- ^Fischer, Stephen Roger (4 April 2004).A History of Writing.Globalities. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 189–194.ISBN1-86189-101-6.Retrieved3 April2009.

- ^abcdByon, Andrew Sangpil (2017).Modern Korean Grammar: A Practical Guide.Taylor & Francis. pp. 3–18.ISBN978-1351741293.

- ^Choo, Miho; O'Grady, William (1996).Handbook of Korean Vocabulary: An Approach to Word Recognition and Comprehension.University of Hawaii Press. pp. ix.ISBN0824818156.

- ^"사전소개 | 겨레말큰사전남북공동편찬사업회".www.gyeoremal.or.kr(in Korean).Retrieved23 November2022.

- ^"우리말 70%가 한자말? 일제가 왜곡한 거라네".The Hankyoreh(in Korean). 11 September 2009.Retrieved23 November2022.

- ^Ledyard 1998,p. 32-33.

- ^abcTaylor, I. & Taylor, M. M. (2014).Writing and Literacy in Chinese, Korean and Japanese: Revised Edition.(pp. 172–174.) Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins North America. p.172

- ^Ledyard 1998,p. 34.

- ^Ledyard 1998,p. 34-36.

- ^Ledyard 1998,p. 36-37.

- ^Ledyard 1998,p. 37.

- ^Li, Y. (2014).The Chinese Writing System in Asia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective.Chapter 10. New York, NY: Routledge Press.

- ^abcNam, P. (1994). 'On the Relations between Hyangchal and Kwukyel' inThe Theoretical Issues in Korean Linguistics.Kim-Renaud, Y. (ed.) (pp. 419–424.) Stanford, CA: Leland Stanford University Press.

- ^abcHannas, W. C. (1997).Asia's Orthographic Dilemma.O`ahu, HI: University of Hawai`i Press. pp. 55–64.

- ^"문자 생활과 한글"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 25 March 2023.

- ^"New Korean-English Dictionary published".Korean Central News Agency.28 May 2003. Archived fromthe originalon 12 October 2007.

- ^Hannas 1997: 71. "A balance was struck in August 1976, when the Ministry of Education agreed to keep Chinese characters out of the elementary schools and teach the 1,800 characters in special courses, not as part of Korean language or any other substantive curricula. This is where things stand at present"

- ^Hannas 1997: 68–69

- ^한문 교육용 기초 한자 (2000),page 15 (추가자: characters added, 제외자: characters removed)

- ^"Hangeul advocates oppose Hanja classes",The Korea Herald,2013-07-03.

- ^Kim, Mihyang (10 January 2018)."[단독] 교육부, 초등교과서 한자 병기 정책 폐기"[Exclusive: Ministry of Education drops the planned policy to allow Hanja in elementary school textbooks].Hankyoreh(in Korean).Retrieved15 October2020.

- ^Hannas 1997: 67. "By the end of 1946 and the beginning of 1947, the major newspaperNodong sinmun,mass circulation magazineKulloja,and similar publications began appearing in all-hangul.School textbooks and literary materials converted to all-hangulat the same time or possibly earlier (So 1989:31). "

- ^Hannas 1997: 68. "Although North Korea has removed Chinese characters from its written materials, it has, paradoxically, ended up with an educational program that teachers more characters than either South Korea or Japan, as Table 2 shows."

- ^Hannas 1997: 67. "According to Ko Yong-kun, Kim went on record as early as February 1949, when Chinese characters had already been removed from most DPRK publications, as advocating theirgradualabandonment (1989:25). "

- ^abHannas 1997: 67

- ^Hannas 1997: 67. "Between 1968 and 1969, a four-volume textbook appeared for use in grades 5 through 9 designed to teach 1,500 characters, confirming the applicability of the new policy to the general student population. Another five hundred were added for grades 10 through 12 (Yi Yun-p'yo 1989: 372)."

- ^Hannas 2003: 188–189

- ^Yang, Lina (29 April 2010)."S. Korea bids farewell to warship victims".Xinhua.Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.

- ^Brown 1990: 120

- ^"신라면, 더 쫄깃해진 면발…세계인 울리는 '국가대표 라면'".The Korea Economic Daily.17 February 2016.Retrieved8 June2016.

- ^(in Korean)Naver Hanja Dictionary query of sudo

- ^Choo, Miho (2008).Using Korean: A Guide to Contemporary Usage.Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–92.ISBN978-1139471398.

- ^2003 niên 9 nguyệt 9 nhật triều tiên duyệt binhonBilibili.Retrieved 18 Sep 2020.

- ^Taylor and Taylor 1983: 90

- ^Brown 1990: 119

- ^Patrick Chun Kau Chu. (2008).Onset, Rhyme and Coda Corresponding Rules of the Sino-Korean Characters between Cantonese and KoreanArchived24 September 2015 at theWayback Machine.Paper presented at the 5th Postgraduate Research Forum on Linguistics (PRFL), Hong Kong, China, March 15–16.

Sources

[edit]- Brown, R. A. (1990). "Korean Sociolinguistic Attitudes in Japanese Comparative Perspective".Journal of Asian Pacific Communication.1:117–134.

- DeFrancis, John (1990).The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy.Honolulu:University of Hawaii Press.ISBN0-8248-1068-6.

- Hannas, William C. (1997).Asia's Orthographic Dilemma.Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.ISBN0-8248-1842-3.

- Hannas, William C. (2003).The Writing on the Wall: How Asian Orthography Curbs Creativity.Philadelphia:University of Pennsylvania Press.ISBN0-8122-3711-0.

- Ledyard, Gari K. (1998),The Korean Language Reform of 1446

- Taylor, Insup; Taylor, Martin M. (1983).The psychology of reading.New York: Academic Press.ISBN0-12-684080-6.