Hangul

This article has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Korean alphabet 한글/조선글 Hangul(Hangeul) /Chosŏn'gŭl | |

|---|---|

"Chosŏn'gŭl" (top) and "Hangul" (bottom) | |

| Script type | Featural |

| Creator | Sejong of Joseon |

Time period | 1443CE– present |

| Direction |

|

| Languages | KoreanandJeju(standard) Cia-Cia(limited use) |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hang(286),Hangul (Hangŭl, Hangeul)Jamo(for the jamo subset) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Hangul |

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

|

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

| Transliteration |

|

| Writing systems |

|---|

|

| Abjad |

| Abugida |

| Alphabetical |

| Logographic |

| Syllabic |

| Hybrids |

|

Japanese(Logographic and syllabic) Hangul(Alphabetic and syllabic) |

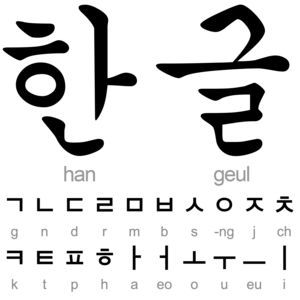

TheKorean alphabet,known asHangul[a](English:/ˈhɑːnɡuːl/HAHN-gool;[1]Korean:한글;Hanja:Hàn 㐎) inSouth KoreaandChosŏn'gŭl(조선글;Triều tiên 㐎) inNorth Korea,is the modernwriting systemfor theKorean language.[2][3][4]The letters for the five basicconsonantsreflect the shape of the speech organs used to pronounce them. They are systematically modified to indicatephoneticfeatures. Thevowelletters are systematically modified for related sounds, making Hangul afeatural writing system.[5][6][7]It has been described as a syllabic alphabet as it combines the features ofalphabeticandsyllabicwriting systems.[8][6]

Hangul was created in 1443 CE by KingSejong the Greatin an attempt to increaseliteracyby serving as a complement (or alternative) to thelogographicSino-KoreanHanja,which had been used by Koreans as their primary script to write the Korean language since as early as theGojoseonperiod (spanning more than a thousand years and ending around 108 BCE), along with the usage ofClassical Chinese.[9][10]The development of the Hangul alphabet is traditionally ascribed to Sejong, fourth king of the Chosŏn (Yi) dynasty.[11]

ModernHangul orthographyuses 24 basic letters: 14 consonant letters[b]and 10 vowel letters.[c]There are also 27 complex letters that are formed by combining the basic letters: 5 tense consonant letters,[d]11 complex consonant letters,[e]and 11 complex vowel letters.[f]Four basic letters in the original alphabet are no longer used: 1 vowel letter[g]and 3 consonant letters.[h]Korean letters are written insyllabicblocks with the alphabetic letters arranged in two dimensions. For example, the South Korean city of Seoul is written as서울,notㅅㅓㅇㅜㄹ.[12]The syllables begin with a consonant letter, then a vowel letter, and then potentially another consonant letter called abatchim(Korean:받침). If the syllable begins with a vowel sound, the consonantㅇ(ng) acts as a silent placeholder. However, when ㅇ starts a sentence or is placed after a long pause, it marks aglottal stop.Syllables may begin with basic or tense consonants but not complex ones. The vowel can be basic or complex, and the second consonant can be basic, complex or a limited number of tense consonants. How the syllable is structured depends if the baseline of the vowel symbol is horizontal or vertical. If the baseline is vertical, the first consonant and vowel are written above the second consonant (if present), but all components are written individually from top to bottom in the case of a horizontal baseline.[12]

As in traditionalChineseandJapanesewriting, as well as many other texts in East Asia, Korean texts were traditionally written top to bottom, right to left, as is occasionally still the way for stylistic purposes. However, Korean is now typically written from left to right withspacesbetween words serving asdividers,unlike in Japanese and Chinese.[7]Hangul is the official writing system throughoutKorea,both North and South. It is a co-official writing system in theYanbian Korean Autonomous PrefectureandChangbai Korean Autonomous CountyinJilin Province,China. Hangul has also seen limited use by speakers of theCia-Cia languagein Indonesia.[13]

Names[edit]

Official names[edit]

| Korean name (North Korea) | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | |

|---|---|

| Hancha | |

| Revised Romanization | Joseon(-)geul |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chosŏn'gŭl |

| IPA | Korean pronunciation:[tso.sɔn.ɡɯl] |

| Korean name (South Korea) | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Han(-)geul |

| McCune–Reischauer | Han'gŭl[14] |

| IPA | Korean pronunciation:[ha(ː)n.ɡɯl] |

The Korean alphabet was originally namedHunminjeong'eum(훈민정음) by KingSejong the Greatin 1443.[10]Hunminjeong'eum is also the document that explained logic and science behind the script in 1446.

The namehangeul(한글) was coined by Korean linguistJu Si-gyeongin 1912. The name combines the ancient Korean wordhan(한), meaning great, andgeul(글), meaning script. The wordhanis used to refer to Korea in general, so the name also means Korean script.[15]It has beenromanizedin multiple ways:

- Hangeulorhan-geulin theRevised Romanization of Korean,which theSouth Koreangovernment uses in English publications and encourages for all purposes.

- Han'gŭlin theMcCune–Reischauersystem, is often capitalized and rendered without thediacriticswhen used as an English word, Hangul, as it appears in many English dictionaries.

- hān kulin theYale romanization,a system recommended for technical linguistic studies.

North Koreanscall the alphabetChosŏn'gŭl(조선글), afterChosŏn,the North Koreanname for Korea.[16]A variant of theMcCune–Reischauersystem is used there for romanization.

Other names[edit]

Until the mid-20th century, the Korean elite preferred to write usingChinese characterscalledHanja.They referred to Hanja asjinseo(진서/ chân thư ) meaning true letters. Some accounts say the elite referred to the Korean alphabet derisively as'amkeul(암클) meaning women's script, and'ahaetgeul(아햇글) meaning children's script, though there is no written evidence of this.[17]

Supporters of the Korean alphabet referred to it asjeong'eum(정음/ chính âm) meaning correct pronunciation,gungmun(국문/ quốc văn) meaning national script, andeonmun(언문/ ngạn văn) meaningvernacularscript.[17]

History[edit]

Creation[edit]

Koreans primarily wrote usingClassical Chinesealongside native phonetic writing systems that predate Hangul by hundreds of years, includingIdu script,Hyangchal,Gugyeoland Gakpil.[18][19][20][21]However, many lower class uneducated Koreans were illiterate due to the difficulty of learning the Korean and Chinese languages, as well as the large number of Chinese characters that are used.[22]To promote literacy among the common people, the fourth king of theJoseondynasty,Sejong the Great,personally created and promulgated a new alphabet.[3][22][23]Although it is widely assumed that King Sejong ordered theHall of Worthiesto invent Hangul, contemporary records such as theVeritable Records of King SejongandJeong Inji's preface to theHunminjeongeum Haeryeemphasize that he invented it himself.[24]

The Korean alphabet was designed so that people with little education could learn to read and write.[25]According to theHunminjeongeum HaeryeEdition, KingSejongexpressed his intention to understand the language of the people in his country and to express their meanings more conveniently in writing. He noted that the shapes of the traditional Chinese characters, as well as factors such as the thickness, stroke count, and order of strokes in calligraphy, were extremely complex, making it difficult for people to recognize and understand them individually. A popular saying about the alphabet is, "A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; even a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days."[26]

The project was completed in late December 1443 or January 1444, and described in 1446 in a document titledHunminjeong'eum(The Proper Sounds for the Education of the People), after which the alphabet itself was originally named.[17]The publication date of theHunminjeongeum,October 9, becameHangul Dayin South Korea. Its North Korean equivalent, Chosŏn'gŭl Day, is on January 15.

Another document published in 1446 and titledHunminjeong'eum Haerye(Hunminjeong'eumExplanation and Examples) was discovered in 1940. This document explains that the design of the consonant letters is based onarticulatory phoneticsand the design of the vowel letters is based on the principles ofyin and yangandvowel harmony.[27]After the creation of Hangul, people from the lower class or the commoners had a chance to be literate. They learned how to read and write Korean, not just the upper classes and literary elite. They learn Hangul independently without formal schooling or such.[28]

Opposition[edit]

The Korean alphabet faced opposition in the 1440s by the literary elite, includingChoe Manriand otherKorean Confucianscholars. They believedHanjawas the only legitimate writing system. They also saw the circulation of the Korean alphabet as a threat to their status.[22]However, the Korean alphabet enteredpopular cultureas King Sejong had intended, used especially by women and writers of popular fiction.[29]

King Yeonsangunbanned the study and publication of the Korean alphabet in 1504, after a document criticizing the king was published.[30]Similarly,King Jungjongabolished the Ministry of Eonmun, a governmental institution related to Hangul research, in 1506.[31]

Revival[edit]

The late 16th century, however, saw a revival of the Korean alphabet asgasaandsijopoetry flourished. In the 17th century, the Korean alphabet novels became a majorgenre.[32]However, the use of the Korean alphabet had gone withoutorthographical standardizationfor so long that spelling had become quite irregular.[29]

In 1796, theDutchscholarIsaac Titsinghbecame the first person to bring a book written in Korean to theWestern world.His collection of books included the Japanese bookSangoku Tsūran Zusetsu(An Illustrated Description of Three Countries) byHayashi Shihei.[33]This book, which was published in 1785, described theJoseon Kingdom[34]and the Korean alphabet.[35]In 1832, theOriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Irelandsupported the posthumous abridged publication of Titsingh's French translation.[36]

Thanks to growingKorean nationalism,theGabo Reformists' push, and Western missionaries' promotion of the Korean alphabet in schools and literature,[37]the Hangul Korean alphabet was adopted in official documents for the first time in 1894.[30]Elementary school texts began using the Korean alphabet in 1895, andTongnip Sinmun,established in 1896, was the first newspaper printed in both Korean and English.[38]

Reforms and suppression under Japanese rule[edit]

After the Japanese annexation, which occurred in 1910,Japanesewas made the official language of Korea. However, the Korean alphabet was still taught in Korean-established schools built after the annexation and Korean was written in a mixed Hanja-Hangul script, where most lexical roots were written in Hanja and grammatical forms in the Korean alphabet. Japan banned earlier Korean literature from public schooling, which becamemandatoryfor children.[39]

Theorthography of the Korean alphabetwas partially standardized in 1912, when the vowelarae-a(ㆍ)—which has now disappeared from Korean—was restricted toSino-Koreanroots: theemphatic consonantswere standardized toㅺ, ㅼ, ㅽ, ㅆ, ㅾand final consonants restricted toㄱ, ㄴ, ㄹ, ㅁ, ㅂ, ㅅ, ㅇ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ.Long vowelswere marked by a diacritic dot to the left of the syllable, but this was dropped in 1921.[29]

A second colonial reform occurred in 1930. Thearae-awas abolished: the emphatic consonants were changed toㄲ, ㄸ, ㅃ, ㅆ, ㅉand more final consonantsㄷ, ㅈ, ㅌ, ㅊ, ㅍ, ㄲ, ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅄwere allowed, making the orthography moremorphophonemic.The double consonantㅆwas written alone (without a vowel) when it occurred between nouns, and the nominative particle가was introduced after vowels, replacing이.[29]

Ju Si-gyeong,the linguist who had coined the term Hangul to replaceEonmunor Vulgar Script in 1912, established the Korean Language Research Society (later renamed theHangul Society), which further reformed orthography withStandardized System of Hangulin 1933. The principal change was to make the Korean alphabet as morphophonemically practical as possible given the existing letters.[29]A system fortransliterating foreign orthographieswas published in 1940.

Japan banned the Korean language from schools and public offices in 1938 and excluded Korean courses from the elementary education in 1941 as part of a policy ofcultural genocide.[40][41]

Further reforms[edit]

The definitive modern Korean alphabet orthography was published in 1946, just afterKorean independencefrom Japanese rule. In 1948, North Koreaattempted to make the script perfectly morphophonemic through the addition of new letters,and, in 1953,Syngman Rheein South Korea attempted to simplify the orthography by returning to the colonial orthography of 1921, but both reforms were abandoned after only a few years.[29]

BothNorth KoreaandSouth Koreahave used the Korean alphabet ormixed scriptas their official writing system, with ever-decreasing use of Hanja especially in the North.

In South Korea[edit]

Beginning in the 1970s, Hanja began to experience a gradual decline in commercial or unofficial writing in the South due to government intervention, with some South Korean newspapers now only using Hanja as abbreviations or disambiguation of homonyms. However, as Korean documents, history, literature and records throughout its history until the contemporary period were written primarily inLiterary Chineseusing Hanja as its primary script, a good working knowledge of Chinese characters especially in academia is still important for anyone who wishes to interpret and study older texts from Korea, or anyone who wishes to read scholarly texts in the humanities.[42]

A high proficiency in Hanja is also useful for understanding the etymology of Sino-Korean words as well as to enlarge one's Korean vocabulary.[42]

In North Korea[edit]

North Korea instated Hangul as its exclusive writing system in 1949 on the orders ofKim Il Sungof theWorkers' Party of Korea,and officially banned the use of Hanja.[43]

Non-Korean languages[edit]

Systemsthat employed Hangul letters with modified rules were attempted by linguists such asHsu Tsao-teandAng Ui-jinto transcribeTaiwanese Hokkien,aSinitic language,but the usage ofChinese charactersultimately ended up being the most practical solution and was endorsed by theMinistry of Education (Taiwan).[44][45][46]

TheHunminjeong'eum Societyin Seoul attempted to spread the use of Hangul to unwritten languages of Asia.[47]In 2009, it was unofficially adopted by the town ofBaubau,inSoutheast Sulawesi,Indonesia, to write theCia-Cia language.[48][49][50][51]

A number of Indonesian Cia-Cia speakers who visited Seoul generated large media attention in South Korea, and they were greeted on their arrival byOh Se-hoon,themayor of Seoul.[52]

Letters[edit]

Letters in the Korean alphabet are calledjamo(자모). There are 14consonants(자음) and 10vowels(모음) used in the modern alphabet. They were first named inHunmongjahoe,ahanjatextbook written byChoe Sejin.Additionally, there are 27 complex letters that are formed by combining the basic letters: 5 tense consonant letters, 11 complex consonant letters, and 11 complex vowel letters.

In typography design and in IME automata, the letters that make up a block are calledjaso(자소).

Consonants[edit]

The chart below shows all 19 consonants in South Korean alphabetic order withRevised Romanizationequivalents for each letter and pronunciation inIPA(seeKorean phonologyfor more).

| Hangul | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Romanization | g | kk | n | d | tt | r | m | b | pp | s | ss | '[i] | j | jj | ch | k | t | p | h |

| IPA | /k/ | /k͈/ | /n/ | /t/ | /t͈/ | /ɾ/ | /m/ | /p/ | /p͈/ | /s/ | /s͈/ | silent | /t͡ɕ/ | /t͈͡ɕ͈/ | /t͡ɕʰ/ | /kʰ/ | /tʰ/ | /pʰ/ | /h/ | |

| Final | Romanization | k | k | n | t | – | l | m | p | – | t | t | ng | t | – | t | k | t | p | t |

| g | kk | n | d | l | m | b | s | ss | ng | j | ch | k | t | p | h | |||||

| IPA | /k̚/ | /n/ | /t̚/ | – | /ɭ/ | /m/ | /p̚/ | – | /t̚/ | /ŋ/ | /t̚/ | – | /t̚/ | /k̚/ | /t̚/ | /p̚/ | /t̚/ | |||

ㅇ issilentsyllable-initially and is used as a placeholder when the syllable starts with a vowel. ㄸ, ㅃ, and ㅉ are never used syllable-finally.

Consonants are broadly categorized into either obstruents (sounds produced when airflow either completely stops (i.e., aplosiveconsonant) or passes through a narrow opening (i.e., africative)) or sonorants (sounds produced when air flows out with little to no obstruction through the mouth, nose, or both).[53]The chart below lists the Korean consonants by their respective categories and subcategories.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstruent | Stop (plosive) | Lax | p(ㅂ) | t(ㄷ) | k(ㄱ) | ||

| Tense | p͈(ㅃ) | t͈(ㄸ) | k͈(ㄲ) | ||||

| Aspirated | pʰ(ㅍ) | tʰ(ㅌ) | kʰ(ㅋ) | ||||

| Fricative | Lax | s(ㅅ) | h(ㅎ) | ||||

| Tense | s͈(ㅆ) | ||||||

| Affricate | Lax | t͡ɕ(ㅈ) | |||||

| Tense | t͈͡ɕ͈(ㅉ) | ||||||

| Aspirated | t͡ɕʰ(ㅊ) | ||||||

| Sonorant | Nasal | m(ㅁ) | n(ㄴ) | ŋ(ㅇ) | |||

| Liquid (lateral approximant) | l(ㄹ) | ||||||

All Korean obstruents arevoicelessin that the larynx does not vibrate when producing those sounds and are further distinguished by degree of aspiration and tenseness. The tensed consonants are produced by constricting the vocal cords while heavily aspirated consonants (such as the Korean ㅍ,/pʰ/) are produced by opening them.[53]

Korean sonorants are voiced.

Consonant assimilation[edit]

The pronunciation of a syllable-final consonant (which may already differ from its syllable-initial sound) may be affected by the following letter, and vice-versa. The table below describes theseassimilationrules. Spaces are left blank when no modification is made to the normal syllable-final sound.

| Preceding syllable block's final letter-sound | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㄱ

(k) |

ㄲ

(k) |

ㄴ

(n) |

ㄷ

(t) |

ㄹ

(l) |

ㅁ

(m) |

ㅂ

(p) |

ㅅ

(t) |

ㅆ

(t) |

ㅇ

(ng) |

ㅈ

(t) |

ㅊ

(t) |

ㅋ

(k) |

ㅌ

(t) |

ㅍ

(p) |

ㅎ

(t) | ||

| Subsequent syllable block's initial letter | ㄱ(g) | k+k | n+g | t+g | l+g | m+g | b+g | t+g | - | t+g | t+g | t+g | p+g | h+k | |||

| ㄴ(n) | ng+n | n+n | l+n | m+n | m+n | t+n | n+t | t+n | t+n | t+n | p+n | h+n | |||||

| ㄷ(d) | k+d | n+d | t+t | l+d | m+d | p+d | t+t | t+t | t+t | t+t | k+d | t+t | p+d | h+t | |||

| ㄹ(r) | g+n | n+n | l+l | m+n | m+n | - | ng+n | r | |||||||||

| ㅁ(m) | g+m | n+m | t+m | l+m | m+m | m+m | t+m | - | ng+m | t+m | t+m | k+d | t+m | p+m | h+m | ||

| ㅂ(b) | g+b | p+p | t+b | - | |||||||||||||

| ㅅ(s) | ss+s | ||||||||||||||||

| ㅇ(∅) | g | kk+h | n | t | r | m | p | s | ss | ng+h | t+ch | t+ch | k+h | t+ch | p+h | h | |

| ㅈ(j) | t+ch | ||||||||||||||||

| ㅎ(h) | k | kk+h | n+h | t | r/

l+h |

m+h | p | t | - | t+ch | t+ch | k | t | p | - | ||

Consonant assimilation occurs as a result ofintervocalic voicing.When surrounded by vowels or sonorant consonants such as ㅁ or ㄴ, a stop will take on the characteristics of its surrounding sound. Since plain stops (like ㄱ /k/) are produced with relaxed vocal cords that are not tensed, they are more likely to be affected by surrounding voiced sounds (which are produced by vocal cords that are vibrating).[53]

Below are examples of how lax consonants (ㅂ /p/, ㄷ /t/, ㅈ/t͡ɕ/,ㄱ /k/) change due to location in a word. Letters in bolded interface show intervocalic weakening, or the softening of the lax consonants to their sonorous counterparts.[53]

ㅂ

- 밥 [bap̚] – 'rice'

- 보리밥 [boɾibap̚] – 'barley mixed with rice'

ㄷ

- 다 [da] – 'all'

- 맏 [mat̚] – 'oldest'

- 맏아들 [madadɯɭ] – 'oldest son'

ㅈ

- 죽 [t͡ɕuk] – 'porridge'

- 콩죽 [kʰoŋd͡ʑuk̚] – 'bean porridge'

ㄱ

- 공 [goŋ] – 'ball'

- 새 공 [sɛgoŋ] – 'new ball'

The consonants ㄹ and ㅎ also experience weakening. The liquid ㄹ, when in an intervocalic position, will be weakened to a [ɾ]. For example, the final ㄹ in the word 말 ([maɭ], 'word') changes when followed by the subject marker 이 (a vowel), and changes to a [ɾ] to become [maɾi].

ㅎ /h/ is very weak and is usually deleted in Korean words, as seen in words like 괜찮아요 /kwɛnt͡ɕʰanhajo/ [kwɛnt͡ɕʰanajo]. However, instead of being completely deleted, it leaves remnants by devoicing the following sound or by acting as a glottal stop.[53]

Lax consonants are tensed when following other obstruents due to the fact that the first obstruent's articulation is not released. Tensing can be seen in words like 입구 ('entrance') /ipku/ which is pronounced as [ip̚k͈u].

Consonants in the Korean alphabet can be combined into one of 11consonant clusters,which always appear in the final position in a syllable block. They are: ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄶ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ, ㄽ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅀ, and ㅄ.

| Consonant cluster combinations

(e.g. [in isolation] 닭dak;[preceding another syllable block] 없다 –eop-da,앉아anj-a) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preceding syllable block's final letter | ㄳ

(gs) |

ㄵ

(nj) |

ㄶ

(nh) |

ㄺ

(lg) |

ㄻ

(lm) |

ㄼ

(lb) |

ㄽ

(ls) |

ㄾ

(lt) |

ㄿ

(lp) |

ㅀ

(lh) |

ㅄ

(bs) | |

| (pronunciation in isolation) | k | n | n | korl* | m | lorp** | l | l | p | l | p | |

| Subsequent block's initial letter | ㅇ(∅) | k+s | n+j | n+h | l+g | l+m | l+b | l+s | l+t | l+p | l+h | p+s |

| ㄷ(d) | k+d | n+d | n+t | k+d | m+d | l+dorp+d** | l+d | l+d | p+d | l+t | p+d | |

* Before ㄱ, the cluster ㄺ is pronounced asl(e.g., 맑게malge[mal.k͈e]).

** For certain words, ㄼ may be pronounced asp(e.g., 밟다bapda[pa:p̚.t͈a], 넓죽하다neopjukhada[nʌp̚.t͈ɕu.kʰa.da]).

In cases where consonant clusters are followed by words beginning with ㅇ, the consonant cluster is resyllabified through a phonological phenomenon calledliaison.In words where the first consonant of the consonant cluster is ㅂ,ㄱ, or ㄴ (the stop consonants), articulation stops and the second consonant cannot be pronounced without releasing the articulation of the first once. Hence, in words like 값 /kaps/ ('price'), the ㅅ cannot be articulated and the word is thus pronounced as [kap̚]. The second consonant is usually revived when followed by a word with initial ㅇ (값이 → [kap̚.si]. Other examples include 삶 (/salm/ [sam], 'life'). The ㄹ in the final consonant cluster is generally lost in pronunciation, however when followed by the subject marker 이, the ㄹ is revived and the ㅁ takes the place of the blank consonant ㅇ. Thus, 삶이 is pronounced as [sal.mi].

In cases where clusters are followed by syllables beginning with a consonant (e.g., ㄷ as shown above), the cluster generally maintains its isolated pronunciation; however, the cluster's lost consonant may sometimes revive and assimilate into the following syllable's consonant. For example, in 않다 (/anh.ta/ → [an.tʰa]) the lost ㅎ is assimilated into the following syllable and aspirates ㄷ. Similarly, in 앉하다 (/antɕ.ha.ta/ → [an.tɕʰa.da]) the lost ㅈ is revived and aspirated by the following ㅎ.[55]

Vowels[edit]

The chart below shows the 21 vowels used in the modern Korean alphabet in South Korean alphabetic order withRevised Romanizationequivalents for each letter and pronunciation inIPA(seeKorean phonologyfor more).

| Hangul | ㅏ | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revised Romanization | a | ae | ya | yae | eo | e | yeo | ye | o | wa | wae | oe | yo | u | wo | we | wi | yu | eu | ui/

yi |

i |

| IPA | /a/ | /ɛ/ | /ja/ | /jɛ/ | /ʌ/ | /e/ | /jʌ/ | /je/ | /o/ | /wa/ | /wɛ/ | /ø/~[we] | /jo/ | /u/ | /wʌ/ | /we/ | /y/~[ɥi] | /ju/ | /ɯ/ | /ɰi/ | /i/ |

The vowels are generally separated into two categories: monophthongs and diphthongs. Monophthongs are produced with a single articulatory movement (hence the prefix mono), while diphthongs feature an articulatory change. Diphthongs have two constituents: a glide (or a semivowel) and a monophthong. There is some disagreement about exactly how many vowels are considered Korean's monophthongs; the largest inventory features ten, while some scholars have proposed eight or nine.[who?]This divergence reveals two issues: whether Korean has two front rounded vowels (i.e. /ø/ and /y/); and, secondly, whether Korean has three levels of front vowels in terms of vowel height (i.e. whether /e/ and /ɛ/ are distinctive).[54]Actual phonological studies done by studying formant data show that current speakers of Standard Korean do not differentiate between the vowels ㅔ and ㅐ in pronunciation.[56]

Alphabetic order[edit]

Alphabetic orderin the Korean alphabet is called theganadaorder, (가나다순) after the first three letters of the alphabet. The alphabetical order of the Korean alphabet does not mix consonants and vowels. Rather, first arevelar consonants,thencoronals,labials,sibilants,etc. The vowels come after the consonants.[57]

Thecollationorder of Korean in Unicode is based on the South Korean order.

Historical orders[edit]

The order from theHunminjeongeumin 1446 was:[58]

- ㄱ ㄲ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㄸ ㅌ ㄴ ㅥ ㅂ ㅃ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅅ ㅆ ㆆ ㅎ ㆅ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ

- ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ

This is the basis of the modern alphabetic orders. It was before the development of the Korean tense consonants and the double letters that represent them, and before the conflation of the lettersㅇ(null) andㆁ(ng). Thus, when theNorth KoreanandSouth Koreangovernments implemented full use of the Korean alphabet, they ordered these letters differently, with North Korea placing new letters at the end of the alphabet and South Korea grouping similar letters together.[59][60]

North Korean order[edit]

The double letters are placed after all the single letters (except the null initialㅇ,which goes at the end).

- ㄱ ㄴ ㄷ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅅ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㄸ ㅃ ㅆ ㅉ ㅇ

- ㅏ ㅑ ㅓ ㅕ ㅗ ㅛ ㅜ ㅠ ㅡ ㅣ ㅐ ㅒ ㅔ ㅖ ㅚ ㅟ ㅢ ㅘ ㅝ ㅙ ㅞ

All digraphs andtrigraphs,including the old diphthongsㅐandㅔ,are placed after the simple vowels, again maintaining Choe's alphabetic order.

The order of the final letters (받침) is:

- (none)ㄱ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅄ ㅅ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㅆ

(None means there is no final letter.)

Unlike when it is initial, thisㅇis pronounced, as the nasalㅇng,which occurs only as a final in the modern language. The double letters are placed to the very end, as in the initial order, but the combined consonants are ordered immediately after their first element.[59]

South Korean order[edit]

In the Southern order, double letters are placed immediately after their single counterparts:

- ㄱ ㄲ ㄴ ㄷ ㄸ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅃ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

- ㅏ ㅐ ㅑ ㅒ ㅓ ㅔ ㅕ ㅖ ㅗ ㅘ ㅙ ㅚ ㅛ ㅜ ㅝ ㅞ ㅟ ㅠ ㅡ ㅢ ㅣ

The modernmonophthongalvowels come first, with the derived forms interspersed according to their form:iis added first, theniotated,then iotated with addedi.Diphthongsbeginning withware ordered according to their spelling, asㅗorㅜplus a second vowel, not as separatedigraphs.

The order of the final letters is:

- (none)ㄱ ㄲ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅄ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

Every syllable begins with a consonant (or the silent ㅇ) that is followed by a vowel (e.g.ㄷ+ㅏ=다). Some syllables such as달and닭have a final consonant or final consonant cluster (받침). Thus, 399 combinations are possible for two-letter syllables and 10,773 possible combinations for syllables with more than two letters (27 possible final endings), for a total of 11,172 possible combinations of Korean alphabet letters to form syllables.[59]

The sort order including archaic Hangul letters defined in the South Korean national standardKS X 1026-1is:[61]

- Initial consonants: ᄀ, ᄁ, ᅚ, ᄂ, ᄓ, ᄔ, ᄕ, ᄖ, ᅛ, ᅜ, ᅝ, ᄃ, ᄗ, ᄄ, ᅞ, ꥠ, ꥡ, ꥢ, ꥣ, ᄅ, ꥤ, ꥥ, ᄘ, ꥦ, ꥧ, ᄙ, ꥨ, ꥩ, ꥪ, ꥫ, ꥬ, ꥭ, ꥮ, ᄚ, ᄛ, ᄆ, ꥯ, ꥰ, ᄜ, ꥱ, ᄝ, ᄇ, ᄞ, ᄟ, ᄠ, ᄈ, ᄡ, ᄢ, ᄣ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ꥲ, ᄧ, ᄨ, ꥳ, ᄩ, ᄪ, ꥴ, ᄫ, ᄬ, ᄉ, ᄭ, ᄮ, ᄯ, ᄰ, ᄱ, ᄲ, ᄳ, ᄊ, ꥵ, ᄴ, ᄵ, ᄶ, ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ, ᄺ, ᄻ, ᄼ, ᄽ, ᄾ, ᄿ, ᅀ, ᄋ, ᅁ, ᅂ, ꥶ, ᅃ, ᅄ, ᅅ, ᅆ, ᅇ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ꥷ, ᅌ, ᄌ, ᅍ, ᄍ, ꥸ, ᅎ, ᅏ, ᅐ, ᅑ, ᄎ, ᅒ, ᅓ, ᅔ, ᅕ, ᄏ, ᄐ, ꥹ, ᄑ, ᅖ, ꥺ, ᅗ, ᄒ, ꥻ, ᅘ, ᅙ, ꥼ, (filler;

U+115F) - Medial vowels: (filler;

U+1160), ᅡ, ᅶ, ᅷ, ᆣ, ᅢ, ᅣ, ᅸ, ᅹ, ᆤ, ᅤ, ᅥ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅦ, ᅧ, ᆥ, ᅽ, ᅾ, ᅨ, ᅩ, ᅪ, ᅫ, ᆦ, ᆧ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ힰ, ᆁ, ᆂ, ힱ, ᆃ, ᅬ, ᅭ, ힲ, ힳ, ᆄ, ᆅ, ힴ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ᆈ, ᅮ, ᆉ, ᆊ, ᅯ, ᆋ, ᅰ, ힵ, ᆌ, ᆍ, ᅱ, ힶ, ᅲ, ᆎ, ힷ, ᆏ, ᆐ, ᆑ, ᆒ, ힸ, ᆓ, ᆔ, ᅳ, ힹ, ힺ, ힻ, ힼ, ᆕ, ᆖ, ᅴ, ᆗ, ᅵ, ᆘ, ᆙ, ힽ, ힾ, ힿ, ퟀ, ᆚ, ퟁ, ퟂ, ᆛ, ퟃ, ᆜ, ퟄ, ᆝ, ᆞ, ퟅ, ᆟ, ퟆ, ᆠ, ᆡ, ᆢ - Final consonants: (none), ᆨ, ᆩ, ᇺ, ᇃ, ᇻ, ᆪ, ᇄ, ᇼ, ᇽ, ᇾ, ᆫ, ᇅ, ᇿ, ᇆ, ퟋ, ᇇ, ᇈ, ᆬ, ퟌ, ᇉ, ᆭ, ᆮ, ᇊ, ퟍ, ퟎ, ᇋ, ퟏ, ퟐ, ퟑ, ퟒ, ퟓ, ퟔ, ᆯ, ᆰ, ퟕ, ᇌ, ퟖ, ᇍ, ᇎ, ᇏ, ᇐ, ퟗ, ᆱ, ᇑ, ᇒ, ퟘ, ᆲ, ퟙ, ᇓ, ퟚ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᆳ, ᇖ, ᇗ, ퟛ, ᇘ, ᆴ, ᆵ, ᆶ, ᇙ, ퟜ, ퟝ, ᆷ, ᇚ, ퟞ, ퟟ, ᇛ, ퟠ, ᇜ, ퟡ, ᇝ, ᇞ, ᇟ, ퟢ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ᇢ, ᆸ, ퟣ, ᇣ, ퟤ, ퟥ, ퟦ, ᆹ, ퟧ, ퟨ, ퟩ, ᇤ, ᇥ, ᇦ, ᆺ, ᇧ, ᇨ, ᇩ, ퟪ, ᇪ, ퟫ, ᆻ, ퟬ, ퟭ, ퟮ, ퟯ, ퟰ, ퟱ, ퟲ, ᇫ, ퟳ, ퟴ, ᆼ, ᇰ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ퟵ, ᇱ, ᇲ, ᇮ, ᇯ, ퟶ, ᆽ, ퟷ, ퟸ, ퟹ, ᆾ, ᆿ, ᇀ, ᇁ, ᇳ, ퟺ, ퟻ, ᇴ, ᇂ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ, ᇹ

-

Sort order of Hangul consonants defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1

-

Sort order of Hangul vowels defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1

Letter names[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(November 2021) |

Letters in the Korean alphabet were named by Korean linguistChoe Sejinin 1527. South Korea uses Choe's traditional names, most of which follow the format ofletter+i+eu+letter.Choe described these names by listing Hanja characters with similar pronunciations. However, as the syllables윽euk,읃eut,and읏eutdid not occur in Hanja, Choe gave those letters the modified names기역giyeok,디귿digeut,and시옷siot,using Hanja that did not fit the pattern (for 기역) or native Korean syllables (for 디귿 and 시옷).[62]

Originally, Choe gaveㅈ,ㅊ,ㅋ,ㅌ,ㅍ,andㅎthe irregular one-syllable names ofji,chi,ḳi,ṭi,p̣i,andhi,because they should not be used as final consonants, as specified inHunminjeongeum.However, after establishment of the new orthography in 1933, which let all consonants be used as finals, the names changed to the present forms.

In North Korea[edit]

The chart below shows names used in North Korea for consonants in the Korean alphabet. The letters are arranged in North Korean alphabetic order, and the letter names are romanised with theMcCune–Reischauersystem, which is widely used in North Korea. The tense consonants are described with the word된toenmeaning hard.

| Consonant | ㄱ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅅ | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | ㄲ | ㄸ | ㅃ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅉ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | 기윽 | 니은 | 디읃 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 시읏 | 지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 | 된기윽 | 된디읃 | 된비읍 | 된시읏 | 이응 | 된지읒 |

| McCR | kiŭk | niŭn | diŭt | riŭl | miŭm | piŭp | siŭt | jiŭt | chiŭt | ḳiŭk | ṭiŭt | p̣iŭp | hiŭt | toen'giŭk | toendiŭt | toenbiŭp | toensiŭt | 'iŭng | toenjiŭt |

In North Korea, an alternative way to refer to a consonant isletter+ŭ(ㅡ), for example, gŭ (그) for the letterㄱ,andssŭ(쓰) for the letterㅆ.

As in South Korea, the names of vowels in the Korean alphabet are the same as the sound of each vowel.

In South Korea[edit]

The chart below shows names used in South Korea for consonants of the Korean alphabet. The letters are arranged in the South Korean alphabetic order, and the letter names are romanised in theRevised Romanizationsystem, which is the officialromanizationsystem of South Korea. The tense consonants are described with the word쌍ssangmeaning double.

| Consonant | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name (Hangul) | 기역 | 쌍기역 | 니은 | 디귿 | 쌍디귿 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 쌍비읍 | 시옷 | 쌍시옷 | 이응 | 지읒 | 쌍지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 |

| Name (romanised) | gi-yeok | ssang-giyeok | ni-eun | digeut | ssang-digeut | ri-eul | mi-eum | bi-eup | ssang-bi-eup | si-ot (shi-ot) | ssang-si-ot (ssang-shi-ot) | 'i-eung | ji-eut | ssang-ji-eut | chi-eut | ḳi-euk | ṭi-eut | p̣i-eup | hi-eut |

Stroke order[edit]

Letters in the Korean alphabet have adopted certain rules ofChinese calligraphy,althoughㅇandㅎuse a circle, which is not used in printed Chinese characters.[63][64]

-

ㄱ(giyeok기역)

-

ㄴ(nieun니은)

-

ㄷ(digeut디귿)

-

ㄹ(rieul리을)

-

ㅁ(mieum미음)

-

ㅂ(bieup비읍)

-

ㅅ(siot시옷)

-

ㅇ(ieung이응)

-

ㅈ(jieut지읒)

-

ㅊ(chieut치읓)

-

ㅋ(ḳieuk키읔)

-

ㅌ(ṭieut티읕)

-

ㅍ(p̣ieup피읖)

-

ㅎ(hieut히읗)

-

ㅏ(a)

-

ㅐ(ae)

-

ㅓ(eo)

-

ㅔ(e)

-

ㅗ(o)

-

ㅜ(u)

-

ㅡ(eu)

For the iotated vowels, which are not shown, the short stroke is simply doubled.

Letter design[edit]

| Part ofa serieson |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

Scripts typically transcribe languages at the level ofmorphemes(logographic scriptslike Hanja), ofsyllables(syllabarieslikekana), ofsegments(alphabeticscripts like theLatin scriptused to write English and many other languages), or, on occasion, ofdistinctive features.The Korean alphabet incorporates aspects of the latter three, grouping sounds intosyllables,using distinct symbols forsegments,and in some cases using distinct strokes to indicatedistinctive featuressuch asplace of articulation(labial,coronal,velar,orglottal) andmanner of articulation(plosive,nasal,sibilant,aspiration) for consonants, andiotation(a precedingi-sound),harmonic classandi-mutationfor vowels.

For instance, the consonantㅌṭ[tʰ]is composed of three strokes, each one meaningful: the top stroke indicatesㅌis a plosive, likeㆆʔ,ㄱg,ㄷd,ㅈj,which have the same stroke (the last is anaffricate,a plosive–fricative sequence); the middle stroke indicates thatㅌis aspirated, likeㅎh,ㅋḳ,ㅊch,which also have this stroke; and the bottom stroke indicates thatㅌis alveolar, likeㄴn,ㄷd,andㄹl.(It is said to represent the shape of the tongue when pronouncing coronal consonants, though this is not certain.) Two obsolete consonants,ㆁandㅱ,have dual pronunciations, and appear to be composed of two elements corresponding to these two pronunciations:[ŋ]~silence forㆁand[m]~[w]forㅱ.

With vowel letters, a short stroke connected to the main line of the letter indicates that this is one of the vowels thatcanbe iotated; this stroke is then doubled when the vowelisiotated. The position of the stroke indicates which harmonic class the vowel belongs to,light(top or right) ordark(bottom or left). In the modern alphabet, an additional vertical stroke indicatesi mutation,derivingㅐ[ɛ],ㅚ[ø],andㅟ[y]fromㅏ[a],ㅗ[o],andㅜ[u].However, this is not part of the intentional design of the script, but rather a natural development from what were originallydiphthongsending in the vowelㅣ[i].Indeed, in manyKorean dialects,[citation needed]including the standarddialect of Seoul,some of these may still be diphthongs. For example, in the Seoul dialect,ㅚmay alternatively be pronounced[we̞],andㅟ[ɥi].Note:ㅔ[e]as a morpheme is ㅓ combined with ㅣ as a vertical stroke. As a phoneme, its sound is not by i mutation ofㅓ[ʌ].

Beside the letters, the Korean alphabet originally employeddiacritic marksto indicatepitch accent.A syllable with a high pitch (거성) was marked with a dot (〮) to the left of it (when writing vertically); a syllable with a rising pitch (상성) was marked with a double dot, like a colon (〯). These are no longer used, as modern Seoul Korean has lost tonality.Vowel lengthhas also been neutralized in Modern Korean[65]and is no longer written.

Consonant design[edit]

The consonant letters fall into fivehomorganicgroups, each with a basic shape, and one or more letters derived from this shape by means of additional strokes. In theHunmin Jeong-eum Haeryeaccount, the basic shapes iconically represent the articulations thetongue,palate,teeth,andthroattake when making these sounds.

| Simple | Aspirated | Tense | |

|---|---|---|---|

| velar | ㄱ | ㅋ | ㄲ |

| fricatives | ㅅ | ㅆ | |

| palatal | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅉ |

| coronal | ㄷ | ㅌ | ㄸ |

| bilabial | ㅂ | ㅍ | ㅃ |

- Velar consonants(아음, nha âma'eum"molar sounds" )

- ㄱg[k],ㅋḳ[kʰ]

- Basic shape:ㄱis a side view of the back of the tongue raised toward the velum (soft palate). (For illustration, access the external link below.)ㅋis derived fromㄱwith a stroke for the burst of aspiration.

- Sibilant consonants(fricative or palatal) (치음, xỉ âmchieum"dental sounds" ):

- ㅅs[s],ㅈj[tɕ],ㅊch[tɕʰ]

- Basic shape:ㅅwas originally shaped like a wedge ∧, without theserifon top. It represents a side view of the teeth.[citation needed]The line toppingㅈrepresents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The stroke toppingㅊrepresents an additional burst of aspiration.

- Coronal consonants(설음, thiệt âmseoreum"lingual sounds" ):

- ㄴn[n],ㄷd[t],ㅌṭ[tʰ],ㄹr[ɾ,ɭ]

- Basic shape:ㄴis a side view of the tip of the tongue raised toward thealveolar ridge(gum ridge). The letters derived fromㄴare pronounced with the same basic articulation. The line toppingㄷrepresents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The middle stroke ofㅌrepresents the burst of aspiration. The top ofㄹrepresents aflapof the tongue.

- Bilabial consonants(순음, thần âmsuneum"labial sounds" ):

- ㅁm[m],ㅂb[p],ㅍp̣[pʰ]

- Basic shape:ㅁrepresents the outline of the lips in contact with each other. The top ofㅂrepresents the release burst of theb.The top stroke ofㅍis for the burst of aspiration.

- Dorsal consonants(후음, hầu âmhueum"throat sounds" ):

- ㅇ'/ng[ŋ],ㅎh[h]

- Basic shape:ㅇis an outline of the throat. Originallyㅇwas two letters, a simple circle for silence (null consonant), and a circle topped by a vertical line,ㆁ,for the nasalng.A now obsolete letter,ㆆ,represented aglottal stop,which is pronounced in the throat and had closure represented by the top line, likeㄱㄷㅈ.Derived fromㆆisㅎ,in which the extra stroke represents a burst of aspiration.

Vowel design[edit]

Vowel letters are based on three elements:

- A horizontal line representing the flat Earth, the essence ofyin.

- A point for the Sun in the heavens, the essence ofyang.(This becomes a short stroke when written with a brush.)

- A vertical line for the upright Human, the neutral mediator between the Heaven and Earth.

Short strokes (dots in the earliest documents) were added to these three basic elements to derive the vowel letter:

Simple vowels[edit]

- Horizontal letters: these are mid-high back vowels.

- brightㅗo

- darkㅜu

- darkㅡeu(ŭ)

- Vertical letters: these were once low vowels.

- brightㅏa

- darkㅓeo(ŏ)

- brightㆍ

- neutralㅣi

Compound vowels[edit]

The Korean alphabet does not have a letter forwsound. Since anoorubefore anaoreobecame a[w]sound, and[w]occurred nowhere else,[w]could always be analyzed as aphonemicooru,and no letter for[w]was needed. However, vowel harmony is observed: darkㅜuwith darkㅓeoforㅝwo;brightㅗowith brightㅏaforㅘwa:

- ㅘwa=ㅗo+ㅏa

- ㅝwo=ㅜu+ㅓeo

- ㅙwae=ㅗo+ㅐae

- ㅞwe=ㅜu+ㅔe

The compound vowels ending inㅣiwere originallydiphthongs.However, several have since evolved into pure vowels:

- ㅐae=ㅏa+ㅣi(pronounced[ɛ])

- ㅔe=ㅓeo+ㅣi(pronounced[e])

- ㅙwae=ㅘwa+ㅣi

- ㅚoe=ㅗo+ㅣi(formerly pronounced[ø],seeKorean phonology)

- ㅞwe=ㅝwo+ㅣi

- ㅟwi=ㅜu+ㅣi(formerly pronounced[y],seeKorean phonology)

- ㅢui=ㅡeu+ㅣi

Iotated vowels[edit]

There is no letter fory.Instead, this sound is indicated by doubling the stroke attached to the baseline of the vowel letter. Of the seven basic vowels, four could be preceded by aysound, and these four were written as a dot next to a line. (Through the influence of Chinese calligraphy, the dots soon became connected to the line:ㅓㅏㅜㅗ.) A precedingysound, called iotation, was indicated by doubling this dot:ㅕㅑㅠㅛyeo, ya, yu, yo.The three vowels that could not be iotated were written with a single stroke:ㅡㆍㅣeu, (arae a), i.

| Simple | Iotated |

|---|---|

| ㅏ | ㅑ |

| ㅓ | ㅕ |

| ㅗ | ㅛ |

| ㅜ | ㅠ |

| ㅡ | |

| ㅣ |

The simple iotated vowels are:

- ㅑyafromㅏa

- ㅕyeofromㅓeo

- ㅛyofromㅗo

- ㅠyufromㅜu

There are also two iotated diphthongs:

- ㅒyaefromㅐae

- ㅖyefromㅔe

The Korean language of the 15th century hadvowel harmonyto a greater extent than it does today. Vowels in grammaticalmorphemeschanged according to their environment, falling into groups that "harmonized" with each other. This affected themorphologyof the language, and Korean phonology described it in terms ofyinandyang:If a root word hadyang('bright') vowels, then most suffixes attached to it also had to haveyangvowels; conversely, if the root hadyin('dark') vowels, the suffixes had to beyinas well. There was a third harmonic group called mediating (neutral in Western terminology) that could coexist with eitheryinoryangvowels.

The Korean neutral vowel wasㅣi.Theyinvowels wereㅡㅜㅓeu, u, eo;the dots are in theyindirections of down and left. Theyangvowels wereㆍㅗㅏə, o, a,with the dots in theyangdirections of up and right. TheHunmin Jeong-eum Haeryestates that the shapes of the non-dotted lettersㅡㆍㅣwere chosen to represent the concepts ofyin,yang,and mediation: Earth, Heaven, and Human. (The letterㆍəis now obsolete except in the Jeju language.)

The third parameter in designing the vowel letters was choosingㅡas the graphic base ofㅜandㅗ,andㅣas the graphic base ofㅓandㅏ.A full understanding of what these horizontal and vertical groups had in common would require knowing the exact sound values these vowels had in the 15th century.

The uncertainty is primarily with the three lettersㆍㅓㅏ.Some linguists reconstruct these as*a,*ɤ,*e,respectively; others as*ə,*e,*a.A third reconstruction is to make them all middle vowels as*ʌ,*ɤ,*a.[66]With the third reconstruction, Middle Korean vowels actually line up in a vowel harmony pattern, albeit with only one front vowel and four middle vowels:

| ㅣ*i | ㅡ*ɯ | ㅜ*u |

| ㅓ*ɤ | ||

| ㆍ*ʌ | ㅗ*o | |

| ㅏ*a |

However, the horizontal lettersㅡㅜㅗeu, u, odo all appear to have been mid to highback vowels,[*ɯ,*u,*o],and thus to have formed a coherent group phonetically in every reconstruction.

Traditional account[edit]

The traditionally accepted account[j][67][unreliable source?]on the design of the letters is that the vowels are derived from various combinations of the following three components:ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ.Here,ㆍsymbolically stands for the (sun in) heaven,ㅡstands for the (flat) earth, andㅣstands for an (upright) human. The original sequence of the Korean vowels, as stated inHunminjeongeum,listed these three vowels first, followed by various combinations. Thus, the original order of the vowels was:ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ.Two positive vowels (ㅗ ㅏ) including oneㆍare followed by two negative vowels including oneㆍ,then by two positive vowels each including two ofㆍ,and then by two negative vowels each including two ofㆍ.

The same theory provides the most simple explanation of the shapes of the consonants as an approximation of the shapes of the most representative organ needed to form that sound. The original order of the consonants in Hunminjeong'eum was:ㄱ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㅌ ㄴ ㅂ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅊ ㅅ ㆆ ㅎ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ.

- ㄱrepresenting the[k]sound geometrically describes its tongue back raised.

- ㅋrepresenting the[kʰ]sound is derived fromㄱby adding another stroke.

- ㆁrepresenting the[ŋ]sound may have been derived fromㅇby addition of a stroke.

- ㄷrepresenting the[t]sound is derived fromㄴby adding a stroke.

- ㅌrepresenting the[tʰ]sound is derived fromㄷby adding another stroke.

- ㄴrepresenting the[n]sound geometrically describes a tongue making contact with an upper palate.

- ㅂrepresenting the[p]sound is derived fromㅁby adding a stroke.

- ㅍrepresenting the[pʰ]sound is a variant ofㅂby adding another stroke.

- ㅁrepresenting the[m]sound geometrically describes a closed mouth.

- ㅈrepresenting the[t͡ɕ]sound is derived fromㅅby adding a stroke.

- ㅊrepresenting the[t͡ɕʰ]sound is derived fromㅈby adding another stroke.

- ㅅrepresenting the[s]sound geometrically describes the sharp teeth.[citation needed]

- ㆆrepresenting the[ʔ]sound is derived fromㅇby adding a stroke.

- ㅎrepresenting the[h]sound is derived fromㆆby adding another stroke.

- ㅇrepresenting the absence of a consonant geometrically describes the throat.

- ㄹrepresenting the[ɾ]and[ɭ]sounds geometrically describes the bending tongue.

- ㅿrepresenting a weakㅅsound describes the sharp teeth, but has a different origin thanㅅ.[clarification needed]

Ledyard's theory of consonant design[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(June 2020) |

(Bottom) Derivation of 'Phags-paw,v,ffrom variants of the letter[h](left) plus a subscript[w],and analogous composition of the Korean alphabetw,v,ffrom variants of the basic letter[p]plus a circle.

Although theHunminjeong'eum Haeryeexplains the design of the consonantal letters in terms ofarticulatory phonetics,as a purely innovative creation, several theories suggest which external sources may have inspired or influenced King Sejong's creation. ProfessorGari Ledyardof Columbia University studied possible connections between Hangul and the Mongol'Phags-pa scriptof theYuan dynasty.He, however, also believed that the role of 'Phags-pa script in the creation of the Korean alphabet was quite limited, stating it should not be assumed that Hangul was derived from 'Phags-pa script based on his theory:

It should be clear to any reader that in the total picture, that ['Phags-pa script's] role was quite limited... Nothing would disturb me more, after this study is published, than to discover in a work on the history of writing a statement like the following: "According to recent investigations, the Korean alphabet was derived fromthe Mongol'sphags-pa script."[68]

Ledyard posits that five of the Korean letters have shapes inspired by 'Phags-pa; a sixth basic letter, the null initialㅇ,was invented by Sejong. The rest of the letters were derived internally from these six, essentially as described in theHunmin Jeong-eum Haerye.However, the five borrowed consonants were not the graphically simplest letters considered basic by theHunmin Jeong-eum Haerye,but instead the consonants basic to Chinese phonology:ㄱ,ㄷ,ㅂ,ㅈ,andㄹ.[citation needed]

TheHunmin Jeong-eumstates that King Sejong adapted theCổ triện(gojeon,GǔSeal Script) in creating the Korean alphabet. TheCổ triệnhas never been identified. The primary meaning ofCổgǔis old (Old Seal Script), frustrating philologists because the Korean alphabet bears no functional similarity to ChineseTriện tựzhuànzìseal scripts.However, Ledyard believesCổgǔmay be a pun onMông cổMěnggǔ"Mongol", and thatCổ triệnis an abbreviation ofMông cổ triện tự"Mongol Seal Script", that is, the formal variant of the 'Phags-pa alphabet written to look like the Chinese seal script. There were 'Phags-pa manuscripts in the Korean palace library, including some in the seal-script form, and several of Sejong's ministers knew the script well. If this was the case, Sejong's evasion on the Mongol connection can be understood in light of Korea's relationship withMingChina after the fall of the MongolYuan dynasty,and of the literati's contempt for the Mongols.[citation needed]

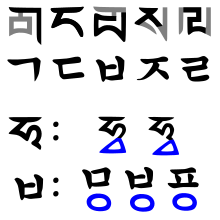

According to Ledyard, the five borrowed letters were graphically simplified, which allowed for consonant clusters and left room to add a stroke to derive the aspirate plosives,ㅋㅌㅍㅊ.But in contrast to the traditional account, the non-plosives (ㆁ ㄴ ㅁ ㅅ) were derived byremovingthe top of the basic letters. He points out that while it is easy to deriveㅁfromㅂby removing the top, it is not clear how to deriveㅂfromㅁin the traditional account, since the shape ofㅂis not analogous to those of the other plosives.[citation needed]

The explanation of the letterngalso differs from the traditional account. Many Chinese words began withng,but by King Sejong's day, initialngwas either silent or pronounced[ŋ]in China, and was silent when these words were borrowed into Korean. Also, the expected shape ofng(the short vertical line left by removing the top stroke ofㄱ) would have looked almost identical to the vowelㅣ[i].Sejong's solution solved both problems: The vertical stroke left fromㄱwas added to the null symbolㅇto createㆁ(a circle with a vertical line on top), iconically capturing both the pronunciation[ŋ]in the middle or end of a word, and the usual silence at the beginning. (The graphic distinction between nullㅇandngㆁwas eventually lost.)

Another letter composed of two elements to represent two regional pronunciations wasㅱ,which transcribed the ChineseinitialVi.This represented eithermorwin various Chinese dialects, and was composed ofㅁ[m] plusㅇ(from 'Phags-pa [w]). In 'Phags-pa, a loop under a letter representedwafter vowels, and Ledyard hypothesized that this became the loop at the bottom ofㅱ.In 'Phags-pa the Chinese initialViis also transcribed as a compound withw,but in its case thewis placed under anh.Actually, the Chinese consonant seriesVi phi phuw,v,fis transcribed in 'Phags-pa by the addition of awunder three graphic variants of the letter forh,and the Korean alphabet parallels this convention by adding thewloop to the labial seriesㅁㅂㅍm,b,p,producing now-obsoleteㅱㅸㆄw,v,f.(Phonetic values in Korean are uncertain, as these consonants were only used to transcribe Chinese.)

As a final piece of evidence, Ledyard notes that most of the borrowed Korean letters were simple geometric shapes, at least originally, but thatㄷd[t] always had a small lip protruding from the upper left corner, just as the 'Phags-paꡊd[t] did. This lip can be traced back to the Tibetan letterདd.[citation needed]

There is also the argument that the original theory, which stated the Hangul consonants to have been derived from the shape of the speaker's lips and tongue during the pronunciation of the consonants (initially, at least), slightly strains credulity.[69]

Hangul supremacy[edit]

Hangul supremacyorHangul scientific supremacyis the claim that the Hangul alphabet is the simplest and most logicalwriting systemin the world.[70]

Proponents of the claim believe Hangul is the most scientific writing system because its characters are based on the shapes of the parts of the human body used to enunciate.[citation needed]For example, the first alphabet, ㄱ, is shaped like the root of the tongue blocking the throat and makes a sound between /k/ and /g/ in English. They also believe that Hangul was designed to be simple to learn, containing only 28 characters in its alphabet with simplistic rules.[citation needed]

Edwin O. ReischauerandJohn K. FairbankofHarvard Universitywrote that "Hangul is perhaps the most scientific system of writing in general use in any country."[71]

Former professor ofLeiden UniversityFrits Vos stated that King Sejong "invented the world's best alphabet," adding, "It is clear that the Korean alphabet is not only simple and logical, but has, moreover, been constructed in a purely scientific way."[72]

Obsolete letters[edit]

This section has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Numerous obsolete Korean letters and sequences are no longer used in Korean. Some of these letters were only used to represent the sounds of Chineserime tables.Some of the Korean sounds represented by these obsolete letters still exist in dialects.

| 13 obsolete consonants

(IPA) |

Soft consonants | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamo | ᄛ | ㅱ | ㅸ | ᄼ | ᄾ | ㅿ | ㆁ | ㅇ | ᅎ | ᅐ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ㆄ | ㆆ | |

| IPA | /ɾ/ | first:/ɱ/

last:/w/ |

/β/ | /s/ | /ɕ/ | /z/ | /ŋ/ | /∅/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ɕ/ | /t͡sʰ/ | /t͡ɕʰ/ | /f/ | /ʔ/ | |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | Vi (미)

/ɱ/ |

Phi (비)

/f/ |

Tâm (심)

/s/ |

Thẩm (심)

/ɕ/ |

Nhật

(ᅀᅵᇙ>일) /z/ |

final position: Nghiệp /ŋ/ | initial position:

Dục /∅/ |

Tinh (정)

/t͡s/ |

Chiếu (조)

/t͡ɕ/ |

Thanh (청)

/t͡sʰ/ |

Xuyên (천)

/t͡ɕʰ/ |

Phu (부)

/fʰ/ |

Ấp (읍)

/ʔ/ | ||

| Toneme | falling | mid to falling | mid to falling | mid | mid to falling | dipping/ mid | mid | mid to falling | mid (aspirated) | high

(aspirated) |

mid to falling

(aspirated) |

high/mid | |||

| Remark | lenisvoiceless dental affricate/voiced dental affricate | lenisvoiceless retroflex affricate/voiced retroflex affricate | aspirated /t͡s/ | aspirated /t͡ɕ/ | glottal stop | ||||||||||

| Equivalents | Standard ChinesePinyin:Tửz[tsɨ]; English: z inzoo orzebra; strong z in Englishzip | identical to the initial position of ng inCantonese | Germanpf | "읗" = "euh" in pronunciation | |||||||||||

| 10 obsolete double consonants

(IPA) |

Hard consonants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamo | ㅥ | ᄙ | ㅹ | ᄽ | ᄿ | ᅇ | ᇮ | ᅏ | ᅑ | ㆅ |

| IPA | /nː/ | /v/ | /sˁ/ | /ɕˁ/ | /j/ | /ŋː/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ɕˁ/ | /hˁ/ | |

| Middle Chinese | hn/nn | hl/ll | bh, bhh | sh | zh | hngw/gh or gr | hng | dz, ds | dzh | hh or xh |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | Tà (사)

/z/ |

Thiền (선)

/ʑ/ |

Tòng (종)

/d͡z/ |

Sàng (상)

/d͡ʑ/ |

Hồng (홍)

/ɦ/ | |||||

| Remark | aspirated | aspirated | unaspiratedfortisvoiceless dental affricate | unaspiratedfortisvoiceless retroflex affricate | guttural | |||||

- 66 obsolete clusters of two consonants: ᇃ, ᄓ /ng/ (like English think), ㅦ /nd/ (as English Monday), ᄖ, ㅧ /ns/ (as English Pennsylvania), ㅨ, ᇉ /tʰ/ (as ㅌ; nt in the language Esperanto), ᄗ /dg/ (similar to ㄲ; equivalent to the word 밖 in Korean), ᇋ /dr/ (like English indrive), ᄘ/ɭ/(similar to French Belle), ㅪ, ㅬ /lz/ (similar to Englishtall zebra), ᇘ, ㅭ/t͡ɬ/(tl or ll; as in Nahuatl), ᇚ /ṃ/ (mh or mg, mm in English hammer,Middle Korean:pronounced as 목 mog with the ㄱ in the word almost silent), ᇛ, ㅮ, ㅯ (similar to ㅂ in Korean 없다), ㅰ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ㅲ, ᄟ, ㅳ bd (assimilated later into ㄸ), ᇣ, ㅶ bj (assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄨ /bj/ (similar to 비추 in Korean verb 비추다bit-chu-dabut without the vowel), ㅷ, ᄪ, ᇥ /ph/ (pha similar to Korean word 돌입하지dol ip-haji), ㅺ sk (assimilated later into ㄲ; English: pick), ㅻ sn (assimilated later into nn in English annal), ㅼ sd (initial position; assimilated later into ㄸ), ᄰ, ᄱ sm (assimilated later into nm), ㅽ sb (initial position; similar sound to ㅃ), ᄵ, ㅾ assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ /θ/, ᄺ/ɸ/, ᄻ, ᅁ, ᅂ /ð/, ᅃ, ᅄ /v/, ᅅ (assimilated later into ㅿ; English z), ᅆ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ㆂ, ㆃ, ᇯ, ᅍ, ᅒ, ᅓ, ᅖ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ

- 17 obsolete clusters of three consonants: ᇄ, ㅩ /rgs/ (similar to "rx" in English name Marx), ᇏ, ᇑ /lmg/ (similar to English Pullman), ᇒ, ㅫ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᇖ, ᇞ, ㅴ, ㅵ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ᄳ, ᄴ

| 1 obsolete vowel

(IPA) |

Extremely soft vowel |

|---|---|

| Jamo | ㆍ |

| IPA | /ʌ/

(also commonly found in theJeju language:/ɒ/, closely similar to vowel:ㅓeo) |

| Letter name | 아래아 (arae-a) |

| Remarks | formerly the base vowelㅡeuin the early development of hangeul when it was considered vowelless, later development into different base vowels for clarification; acts also as a mark that indicates the consonant is pronounced on its own, e.g.s-va-ha → ᄉᆞᄫᅡ 하 |

| Toneme | low |

- 44 obsolete diphthongs and vowel sequences: ᆜ (/j/ or /jɯ/ or /jɤ/, yeu or ehyu); closest similarity to ㅢ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆜ /gj/),ᆝ(/jɒ/; closest similarity to ㅛ,ㅑ, ㅠ, ㅕ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆝ /gj/), ᆢ(/j/; closest similarity to ㅢ, see former example inᆝ(/j/), ᅷ (/au̯/; IcelandicÁ,aw/ow in English allow), ᅸ (/jau̯/; yao or iao;Chinese diphthongiao), ᅹ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅽ /ōu/ ( trừu ㅊᅽ,ch-ieou;like Chinese:chōu), ᅾ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ᆁ, ᆂ (/w/, wo or wh, hw), ᆃ /ow/ (English window), ㆇ, ㆈ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ㆉ (/jø/; yue), ᆉ /wʌ/ or /oɐ/ (pronounced like u'a, in English suave), ᆊ, ᆋ, ᆌ, ᆍ (wu in Englishwould), ᆎ /juə/ or /yua/ (like Chinese: Nguyênyuán), ᆏ /ū/ (like Chinese: Quânjūn), ᆐ, ㆊ /ué/ jujə (ɥe; like Chinese: Quaqué), ㆋ jujəj (ɥej; iyye), ᆓ, ㆌ /jü/ or /juj/ (/jy/ orɥi; yu.i; like GermanJürgen), ᆕ, ᆖ (the same as ᆜ in pronunciation, since there is no distinction due to it extreme similarity in pronunciation), ᆗ ɰju (ehyu or eyyu; like Englishnews), ᆘ, ᆙ /ià/ (like Chinese: Điếmdiàn), ᆚ, ᆛ, ᆟ, ᆠ (/ʔu/), ㆎ (ʌj; oi or oy, similar to English boy).

In the original Korean alphabet system, double letters were used to represent Chinesevoiced(Trọc âm) consonants, which survive in theShanghaineseslackconsonants and were not used for Korean words. It was only later that a similar convention was used to represent the modern tense (faucalized) consonants of Korean.

The sibilant (dental) consonants were modified to represent the two series of Chinese sibilants,alveolarandretroflex,a round vs. sharp distinction (analogous tosvssh) which was never made in Korean, and was even being lost from southern Chinese. The alveolar letters had longer left stems, while retroflexes had longer right stems:

| 5 Place of Articulation (오음, ngũ âm ) in Chinese Rime Table | Tenuis 전청 ( toàn thanh ) |

Aspirate 차청 ( thứ thanh ) |

Voiced 전탁 ( toàn trọc ) |

Sonorant 차탁 ( thứ trọc ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sibilants 치음 ( xỉ âm ) |

치두음 ( xỉ đầu âm ) "tooth-head" |

ᅎ Tinh (정)/t͡s/ |

ᅔ Thanh (청)/t͡sʰ/ |

ᅏ Tòng (종)/d͡z/ |

|

| ᄼ Tâm (심)/s/ |

ᄽ Tà (사)/z/ |

||||

| 정치음 ( chính xỉ âm ) "true front-tooth" |

ᅐ Chiếu (조)/t͡ɕ/ |

ᅕ Xuyên (천)/t͡ɕʰ/ |

ᅑ Sàng (상)/d͡ʑ/ |

||

| ᄾ Thẩm (심)/ɕ/ |

ᄿ Thiền (선)/ʑ/ |

||||

| Coronals 설음 ( thiệt âm ) |

설상음 ( thiệt thượng âm ) "tongue up" |

ᅐ Tri (지)/ʈ/ |

ᅕ Triệt (철)/ʈʰ/ |

ᅑ

Trừng (징)/ɖ/ |

ㄴ Nương (낭)/ɳ/ |

Most common[edit]

- ㆍə(in Modern Korean calledarae-a아래아"lowera"): Presumably pronounced[ʌ],similar to modernㅓ(eo). It is written as a dot, positioned beneath the consonant. Thearae-ais not entirely obsolete, as it can be found in various brand names, and in theJeju language,where it is pronounced[ɒ].Theəformed a medial of its own, or was found in the diphthongㆎəy,written with the dot under the consonant andㅣ(i) to its right, in the same fashion asㅚorㅢ.

- ㅿz(bansiot반시옷"halfs",banchieum반치음): An unusual sound, perhaps IPA[ʝ̃](anasalizedpalatal fricative). Modern Korean words previously spelled withㅿsubstituteㅅorㅇ.

- ㆆʔ(yeorinhieut여린히읗"light hieut" ordoenieung된이응"strong ieung" ): Aglottal stop,lighter thanㅎand harsher thanㅇ.

- ㆁŋ(yedieung옛이응) "old ieung": The original letter for[ŋ];now conflated withㅇieung.(With some computerfontssuch asArial Unicode MS,yesieungis shown as a flattened version ofieung,but the correct form is with a long peak, longer than what one would see on aserifversion ofieung.)

- ㅸβ(gabyeounbieup가벼운비읍,sungyeongeumbieup순경음비읍): IPA[f].This letter appears to be a digraph ofbieupandieung,but it may be more complicated than that—the circle appears to be only coincidentally similar toieung.There were three other, less-common letters for sounds in this section of the Chineserime tables,ㅱw([w]or[m]),ㆄf,andㅹff[v̤].It operates slightly like a followinghin the Latin alphabet (one may think of these letters asbh, mh, ph,andpphrespectively). Koreans do not distinguish these sounds now, if they ever did, conflating thefricativeswith the correspondingplosives.

New Korean Orthography[edit]

To make the Korean alphabet a bettermorphophonologicalfit to the Korean language, North Korea introduced six new letters, which were published in theNew Orthography for the Korean Languageand used officially from 1948 to 1954.[73]

Two obsolete letters were restored:⟨ㅿ⟩(리읃), which was used to indicate an alternation in pronunciation between initial/l/and final/d/;

and⟨ㆆ⟩(히으), which was only pronounced between vowels.

Two modifications of the letterㄹwere introduced, one which is silent finally, and one which doubled between vowels. A hybridㅂ-ㅜletter was introduced for words that alternated between those two sounds (that is, a/b/,which became/w/before a vowel).

Finally, a vowel⟨1⟩was introduced for variableiotation.

| Letter | Pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|

| before a vowel |

before a consonant | |

| /l/ | —[1] | |

| /nn/ | /l/ | |

| ㅿ | /l/ | /t/ |

| ㆆ | —[2] | /◌͈/[3] |

| /w/[4] | /p/ | |

| /j/[5] | /i/ | |

- ^Silence

- ^Makes the following consonant tense, as a final ㅅ does

- ^In standard orthography, combines with a following vowel as ㅘ, ㅙ, ㅚ, ㅝ, ㅞ, ㅟ

- ^In standard orthography, combines with a following vowel as ㅑ, ㅒ, ㅕ, ㅖ, ㅛ, ㅠ

Unicode[edit]

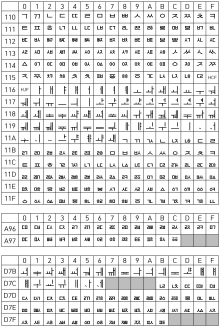

Hangul Jamo (U+1100–U+11FF) and Hangul Compatibility Jamo (U+3130–U+318F) blocks were added to theUnicodeStandard in June 1993 with the release of version 1.1. A separateHangul Syllablesblock (not shown below due to its length) contains pre-composed syllable block characters, which were first added at the same time, although they were relocated to their present locations in July 1996 with the release of version 2.0.[74]

Hangul Jamo Extended-A (U+A960–U+A97F) and Hangul Jamo Extended-B (U+D7B0–U+D7FF) blocks were added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

| Hangul Jamo[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+110x | ᄀ | ᄁ | ᄂ | ᄃ | ᄄ | ᄅ | ᄆ | ᄇ | ᄈ | ᄉ | ᄊ | ᄋ | ᄌ | ᄍ | ᄎ | ᄏ |

| U+111x | ᄐ | ᄑ | ᄒ | ᄓ | ᄔ | ᄕ | ᄖ | ᄗ | ᄘ | ᄙ | ᄚ | ᄛ | ᄜ | ᄝ | ᄞ | ᄟ |

| U+112x | ᄠ | ᄡ | ᄢ | ᄣ | ᄤ | ᄥ | ᄦ | ᄧ | ᄨ | ᄩ | ᄪ | ᄫ | ᄬ | ᄭ | ᄮ | ᄯ |

| U+113x | ᄰ | ᄱ | ᄲ | ᄳ | ᄴ | ᄵ | ᄶ | ᄷ | ᄸ | ᄹ | ᄺ | ᄻ | ᄼ | ᄽ | ᄾ | ᄿ |

| U+114x | ᅀ | ᅁ | ᅂ | ᅃ | ᅄ | ᅅ | ᅆ | ᅇ | ᅈ | ᅉ | ᅊ | ᅋ | ᅌ | ᅍ | ᅎ | ᅏ |

| U+115x | ᅐ | ᅑ | ᅒ | ᅓ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ᅖ | ᅗ | ᅘ | ᅙ | ᅚ | ᅛ | ᅜ | ᅝ | ᅞ | HC F |

| U+116x | HJ F |

ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | ᅤ | ᅥ | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ᅩ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ |

| U+117x | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | ᅶ | ᅷ | ᅸ | ᅹ | ᅺ | ᅻ | ᅼ | ᅽ | ᅾ | ᅿ |

| U+118x | ᆀ | ᆁ | ᆂ | ᆃ | ᆄ | ᆅ | ᆆ | ᆇ | ᆈ | ᆉ | ᆊ | ᆋ | ᆌ | ᆍ | ᆎ | ᆏ |

| U+119x | ᆐ | ᆑ | ᆒ | ᆓ | ᆔ | ᆕ | ᆖ | ᆗ | ᆘ | ᆙ | ᆚ | ᆛ | ᆜ | ᆝ | ᆞ | ᆟ |

| U+11Ax | ᆠ | ᆡ | ᆢ | ᆣ | ᆤ | ᆥ | ᆦ | ᆧ | ᆨ | ᆩ | ᆪ | ᆫ | ᆬ | ᆭ | ᆮ | ᆯ |

| U+11Bx | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ | ᆶ | ᆷ | ᆸ | ᆹ | ᆺ | ᆻ | ᆼ | ᆽ | ᆾ | ᆿ |

| U+11Cx | ᇀ | ᇁ | ᇂ | ᇃ | ᇄ | ᇅ | ᇆ | ᇇ | ᇈ | ᇉ | ᇊ | ᇋ | ᇌ | ᇍ | ᇎ | ᇏ |

| U+11Dx | ᇐ | ᇑ | ᇒ | ᇓ | ᇔ | ᇕ | ᇖ | ᇗ | ᇘ | ᇙ | ᇚ | ᇛ | ᇜ | ᇝ | ᇞ | ᇟ |

| U+11Ex | ᇠ | ᇡ | ᇢ | ᇣ | ᇤ | ᇥ | ᇦ | ᇧ | ᇨ | ᇩ | ᇪ | ᇫ | ᇬ | ᇭ | ᇮ | ᇯ |

| U+11Fx | ᇰ | ᇱ | ᇲ | ᇳ | ᇴ | ᇵ | ᇶ | ᇷ | ᇸ | ᇹ | ᇺ | ᇻ | ᇼ | ᇽ | ᇾ | ᇿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

| Hangul Jamo Extended-A[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+A96x | ꥠ | ꥡ | ꥢ | ꥣ | ꥤ | ꥥ | ꥦ | ꥧ | ꥨ | ꥩ | ꥪ | ꥫ | ꥬ | ꥭ | ꥮ | ꥯ |

| U+A97x | ꥰ | ꥱ | ꥲ | ꥳ | ꥴ | ꥵ | ꥶ | ꥷ | ꥸ | ꥹ | ꥺ | ꥻ | ꥼ | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Hangul Jamo Extended-B[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+D7Bx | ힰ | ힱ | ힲ | ힳ | ힴ | ힵ | ힶ | ힷ | ힸ | ힹ | ힺ | ힻ | ힼ | ힽ | ힾ | ힿ |

| U+D7Cx | ퟀ | ퟁ | ퟂ | ퟃ | ퟄ | ퟅ | ퟆ | ퟋ | ퟌ | ퟍ | ퟎ | ퟏ | ||||

| U+D7Dx | ퟐ | ퟑ | ퟒ | ퟓ | ퟔ | ퟕ | ퟖ | ퟗ | ퟘ | ퟙ | ퟚ | ퟛ | ퟜ | ퟝ | ퟞ | ퟟ |

| U+D7Ex | ퟠ | ퟡ | ퟢ | ퟣ | ퟤ | ퟥ | ퟦ | ퟧ | ퟨ | ퟩ | ퟪ | ퟫ | ퟬ | ퟭ | ퟮ | ퟯ |

| U+D7Fx | ퟰ | ퟱ | ퟲ | ퟳ | ퟴ | ퟵ | ퟶ | ퟷ | ퟸ | ퟹ | ퟺ | ퟻ | ||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

| Hangul Compatibility Jamo[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+313x | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄳ | ㄴ | ㄵ | ㄶ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㄺ | ㄻ | ㄼ | ㄽ | ㄾ | ㄿ | |

| U+314x | ㅀ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅄ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | ㅏ |

| U+315x | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ |

| U+316x | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ | HF | ㅥ | ㅦ | ㅧ | ㅨ | ㅩ | ㅪ | ㅫ | ㅬ | ㅭ | ㅮ | ㅯ |

| U+317x | ㅰ | ㅱ | ㅲ | ㅳ | ㅴ | ㅵ | ㅶ | ㅷ | ㅸ | ㅹ | ㅺ | ㅻ | ㅼ | ㅽ | ㅾ | ㅿ |

| U+318x | ㆀ | ㆁ | ㆂ | ㆃ | ㆄ | ㆅ | ㆆ | ㆇ | ㆈ | ㆉ | ㆊ | ㆋ | ㆌ | ㆍ | ㆎ | |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Parenthesised (U+3200–U+321E) and circled (U+3260–U+327E) Hangul compatibility characters are in theEnclosed CJK Letters and Monthsblock:

| Hangul subset ofEnclosed CJK Letters and Months[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+320x | ㈀ | ㈁ | ㈂ | ㈃ | ㈄ | ㈅ | ㈆ | ㈇ | ㈈ | ㈉ | ㈊ | ㈋ | ㈌ | ㈍ | ㈎ | ㈏ |

| U+321x | ㈐ | ㈑ | ㈒ | ㈓ | ㈔ | ㈕ | ㈖ | ㈗ | ㈘ | ㈙ | ㈚ | ㈛ | ㈜ | ㈝ | ㈞ | |

| ... | (U+3220–U+325F omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| U+326x | ㉠ | ㉡ | ㉢ | ㉣ | ㉤ | ㉥ | ㉦ | ㉧ | ㉨ | ㉩ | ㉪ | ㉫ | ㉬ | ㉭ | ㉮ | ㉯ |

| U+327x | ㉰ | ㉱ | ㉲ | ㉳ | ㉴ | ㉵ | ㉶ | ㉷ | ㉸ | ㉹ | ㉺ | ㉻ | ㉼ | ㉽ | ㉾ | |

| ... | (U+3280–U+32FF omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Half-widthHangul compatibility characters (U+FFA0–U+FFDC) are in theHalfwidth and Fullwidth Formsblock:

| Hangul subset ofHalfwidth and Fullwidth Forms[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| ... | (U+FF00–U+FF9F omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| U+FFAx | HW HF |

ᄀ | ᄁ | ᆪ | ᄂ | ᆬ | ᆭ | ᄃ | ᄄ | ᄅ | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ |

| U+FFBx | ᄚ | ᄆ | ᄇ | ᄈ | ᄡ | ᄉ | ᄊ | ᄋ | ᄌ | ᄍ | ᄎ | ᄏ | ᄐ | ᄑ | ᄒ | |

| U+FFCx | ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | ᅤ | ᅥ | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ᅩ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ||||

| U+FFDx | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | |||||||

| ... | (U+FFE0–U+FFEF omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Korean alphabet in other Unicode blocks:

- Tonemarks forMiddle Korean[75][76][77]are in theCJK Symbols and Punctuationblock: 〮 (

U+302E), 〯 (U+302F) - 11,172 precomposed syllables in the Korean alphabet make up theHangul Syllablesblock (

U+AC00–U+D7A3)

Morpho-syllabic blocks[edit]

Except for a few grammatical morphemes prior to the twentieth century, no letter stands alone to represent elements of the Korean language. Instead, letters are grouped intosyllabicormorphemicblocks of at least two and often three: a consonant or a doubled consonant called theinitial(초성, sơ thanhchoseongsyllable onset), a vowel ordiphthongcalled themedial(중성, trung thanhjungseongsyllable nucleus), and, optionally, a consonant or consonant cluster at the end of the syllable, called thefinal(종성, chung thanhjongseongsyllable coda). When a syllable has no actual initial consonant, thenull initialㅇieungis used as a placeholder. (In the modern Korean alphabet, placeholders are not used for the final position.) Thus, a block contains a minimum of two letters, an initial and a medial. Although the Korean alphabet had historically been organized into syllables, in the modern orthography it is first organized into morphemes, and only secondarily into syllables within those morphemes, with the exception that single-consonant morphemes may not be written alone.

The sets of initial and final consonants are not the same. For instance,ㅇngonly occurs in final position, while the doubled letters that can occur in final position are limited toㅆssandㄲkk.

Not including obsolete letters, 11,172 blocks are possible in the Korean alphabet.[78]

Letter placement within a block[edit]

The placement or stacking of letters in the block follows set patterns based on the shape of the medial.

Consonant and vowel sequences such asㅄbs,ㅝwo,or obsoleteㅵbsd,ㆋüyeare written left to right.

Vowels (medials) are written under the initial consonant, to the right, or wrap around the initial from bottom to right, depending on their shape: If the vowel has a horizontal axis likeㅡeu,then it is written under the initial; if it has a vertical axis likeㅣi,then it is written to the right of the initial; and if it combines both orientations, likeㅢui,then it wraps around the initial from the bottom to the right:

|

|

|

A final consonant, if present, is always written at the bottom, under the vowel. This is called받침batchim"supporting floor":

|

|

| ||||||||||||

A complex final is written left to right:

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

Blocks are always written in phonetic order, initial-medial-final. Therefore:

- Syllables with a horizontal medial are written downward:읍eup;

- Syllables with a vertical medial and simple final are written clockwise:쌍ssang;

- Syllables with a wrapping medial switch direction (down-right-down):된doen;

- Syllables with a complex final are written left to right at the bottom:밟balp.

Block shape[edit]

Normally the resulting block is written within a square. Some recent fonts (for example Eun,[79]HY깊은샘물M[citation needed],and UnJamo[citation needed]) move towards the European practice of letters whose relative size is fixed, and use whitespace to fill letter positions not used in a particular block, and away from the East Asian tradition of square block characters (Phương khối tự). They break one or more of the traditional rules:[clarification needed]

- Do not stretch initial consonant vertically, but leavewhitespacebelow if no lower vowel and/or no final consonant.

- Do not stretch right-hand vowel vertically, but leave whitespace below if no final consonant. (Often the right-hand vowel extends farther down than the left-hand consonant, like adescenderin European typography.)

- Do not stretch final consonant horizontally, but leave whitespace to its left.

- Do not stretch or pad each block to afixed width,but allowkerning(variable width) where syllable blocks with no right-hand vowel and no double final consonant can be narrower than blocks that do have a right-hand vowel or double final consonant.

In Korean, typefaces that do not have a fixed block boundary size are called탈네모 글꼴(tallemo geulkkol,"out of square typeface" ). If horizontal text in the typeface ends up looking top-aligned with aragged bottom edge,the typeface can be called빨랫줄 글꼴(ppallaetjul geulkkol,"clothesline typeface" ).[citation needed]

These fonts have been used as design accents on signs or headings, rather than for typesetting large volumes of body text.

Linear Korean[edit]

You can helpexpand this section with text translated fromthe corresponding articlein Korean.(September 2020)Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

There was a minor and unsuccessful movement in the early twentieth century to abolish syllabic blocks and write the letters individually and in a row, in the fashion of writing theLatin alphabets,instead of the standard convention of모아쓰기(moa-sseugi"assembled writing" ). For example,ㅎㅏㄴㄱㅡㄹwould be written for한글(Hangeul).[80]It is called 풀어쓰기 (pureo-sseugi'unassembled writing').

Avant-garde typographerAhn Sang-soocreated a font for the Hangul Dada exposition that disassembled the syllable blocks; but while it strings out the letters horizontally, it retains the distinctive vertical position each letter would normally have within a block, unlike the older linear writing proposals.[81]

Orthography[edit]

Until the 20th century, no official orthography of the Korean alphabet had been established. Due to liaison, heavy consonant assimilation, dialectal variants and other reasons, a Korean word can potentially be spelled in multiple ways. Sejong seemed to prefermorphophonemicspelling (representing the underlying root forms) rather than aphonemicone (representing the actual sounds). However, early in its history the Korean alphabet was dominated by phonemic spelling. Over the centuries the orthography became partially morphophonemic, first in nouns and later in verbs. The modern Korean alphabet is as morphophonemic as is practical. The difference between phonetic romanization, phonemic orthography and morphophonemic orthography can be illustrated with the phrasemotaneun sarami:

- Phonetic transcription and translation:

motaneun sarami

[mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.ɾa.mi]

a person who cannot do it - Phonemic transcription:

모타는사라미

/mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.la.mi/ - Morphophonemic transcription:

못하는사람이

|mot-ha-nɯn-sa.lam-i| - Morpheme-by-morphemegloss:

못–하–는 사람=이 mot-ha-neun saram=i cannot-do-[attributive] person=[subject]

After theGabo Reformin 1894, theJoseon Dynastyand later theKorean Empirestarted to write all official documents in the Korean alphabet. Under the government's management, proper usage of the Korean alphabet and Hanja, including orthography, was discussed, until the Korean Empire wasannexedby Japan in 1910.

TheGovernment-General of Koreapopularised a writing style that mixed Hanja and the Korean alphabet, and was used in the later Joseon dynasty. The government revised the spelling rules in 1912, 1921 and 1930, to be relatively phonemic.[citation needed]

TheHangul Society,founded byJu Si-gyeong,announced a proposal for a new, strongly morphophonemic orthography in 1933, which became the prototype of the contemporary orthographies in both North and South Korea. After Korea was divided, the North and South revised orthographies separately. The guiding text for orthography of the Korean alphabet is calledHangeul Matchumbeop,whose last South Korean revision was published in 1988 by the Ministry of Education.

Mixed scripts[edit]

Since the Late Joseon dynasty period, variousHanja-Hangul mixed systemswere used. In these systems, Hanja were used for lexical roots, and the Korean alphabet for grammatical words and inflections, much askanjiandkanaare used in Japanese. Hanja have been almost entirely phased out of daily use in North Korea, and in South Korea they are mostly restricted to parenthetical glosses for proper names and for disambiguating homonyms.

Indo-Arabic numeralsare mixed in with the Korean alphabet, e.g.2007년 3월 22일(22 March 2007).

Readability[edit]

Because of syllable clustering, words are shorter on the page than their linear counterparts would be, and the boundaries between syllables are easily visible (which may aid reading, if segmenting words into syllables is more natural for the reader than dividing them into phonemes).[82]Because the component parts of the syllable are relatively simple phonemic characters, the number of strokes per character on average is lower than in Chinese characters. Unlike syllabaries, such as Japanese kana, or Chinese logographs, none of which encode the constituent phonemes within a syllable, the graphic complexity of Korean syllabic blocks varies in direct proportion with the phonemic complexity of the syllable.[83]Like Japanese kana or Chinese characters, and unlike linear alphabets such asthose derived from Latin,Korean orthography allows the reader to utilize both the horizontal and vertical visual fields.[84]Since Korean syllables are represented both as collections of phonemes and as unique-looking graphs, they may allow for both visual and aural retrieval of words from thelexicon.Similar syllabic blocks, when written in small size, can be hard to distinguish from, and therefore sometimes confused with, each other. Examples include 홋/훗/흣 (hot/hut/heut), 퀼/퀄 (kwil/kwol), 홍/흥 (hong/heung), and 핥/핣/핢 (halt/halp/halm).

Style[edit]

The Korean alphabet may be written either vertically or horizontally. The traditional direction is from top to bottom, right to left. Horizontal writing is also used.[85]

InHunmin Jeongeum,the Korean alphabet was printed in sans-serif angular lines of even thickness. This style is found in books published before about 1900, and can be found in stone carvings (on statues, for example).[85]

Over the centuries, an ink-brush style ofcalligraphydeveloped, employing the same style of lines and angles as traditional Korean calligraphy. This brush style is calledgungche(궁체, cung thể), which means Palace Style because the style was mostly developed and used by the maidservants (gungnyeo,궁녀, cung nữ) of the court inJoseon dynasty.

Modern styles that are more suited for printed media were developed in the 20th century. In 1993, new names for bothMyeongjo(Minh triều) andGothicstyles were introduced when Ministry of Culture initiated an effort to standardize typographic terms, and the namesBatang(바탕,meaning background) andDotum(돋움,meaning "stand out" ) replaced Myeongjo and Gothic respectively. These names are also used inMicrosoft Windows.

A sans-serif style with lines of equal width is popular with pencil and pen writing and is often the default typeface of Web browsers. A minor advantage of this style is that it makes it easier to distinguish-eungfrom-ungeven in small or untidy print, as thejongseong ieung(ㅇ) of such fonts usually lacks aserifthat could be mistaken for the short vertical line of the letterㅜ(u).

See also[edit]

- Cyrillization of Korean(Kontsevich System)

- Hangul consonant and vowel tables

- Hangul orthography

- Korean Braille

- Korean language and computers– methods to type the language

- Korean manual alphabet

- Korean mixed script

- Korean phonology

- Korean spelling alphabet

- Myongjo

- Romanization of Korean

Notes[edit]