Hatha Yoga Pradipika

TheHaṭha Yoga Pradīpikā(Sanskrit:haṭhayogapradīpikā,हठयोगप्रदीपिकाor Light on Hatha Yoga) is a classic fifteenth-centurySanskritmanualonhaṭha yoga,written bySvātmārāma,who connects the teaching's lineage toMatsyendranathof theNathas.It is among the most influential surviving texts on haṭha yoga, being one of the three classic texts alongside theGheranda Samhitaand theShiva Samhita.[1]

More recently, eight works of early hatha yoga that may have contributed to theHatha Yoga Pradipikahave been identified.

Title and composition

[edit]| Hatha Yoga Pradipika2.40–41, 2.77, translated by Mallinson & Singleton |

|---|

| As long as thebreath is restrainedin the body, the mind is calm. As long as the gaze is between the eyebrows there is no danger of death. When all the channels have been purified by correctly performing restraints of the breath, the wind easily pierces and enters the aperture of theSushumna. At the end of the breath-retention inkumbhaka,make the mind free of support. Through practising yoga thus one attains therajayogastate.[2] |

Different manuscripts offer different titles for the text, includingHaṭhayogapradīpikā,Haṭhapradīpikā,Haṭhapradī,andHath-Pradipika.[3]It was composed by Svātmārāma in the 15th century as a compilation of the earlier haṭha yoga texts. Svātmārāma incorporates older Sanskrit concepts into his synthesis. He introduces his system as a preparatory stage for physical purification before highermeditationorRaja Yoga.[4]

Summary

[edit]

TheHatha Yoga Pradīpikālists thirty-five earlier Haṭha Yoga masters (siddhas), includingĀdi Nātha,MatsyendranāthandGorakṣanāth.The work consists of 389shlokas(verses) in four chapters that describe topics including purification (Sanskrit:ṣaṭkarma), posture (āsana), breath control (prāṇāyāma), spiritual centres in the body (chakra),kuṇḍalinī,energetic locks (bandha), energy (prāṇa), channels of thesubtle body(nāḍī), and energetic seals (mudrā).[5]

- Chapter 1 deals with setting the proper environment for yoga, the ethical duties of a yogi, and theasanas.

- Chapter 2 deals withpranayamaand thesatkarmas.

- Chapter 3 discusses themudrasand their benefits.

- Chapter 4 deals withmeditationandsamadhias a journey of personal spiritual growth.

It runs in the line ofHinduyoga (as opposed to theBuddhistandJaintraditions) and is dedicated to The First Lord (Ādi Nātha), one of the names of LordŚiva(the Hindu god of destruction and renewal). He is described in several Nāth texts as having imparted the secret of haṭha yoga to his divine consortPārvatī.

Mechanisms

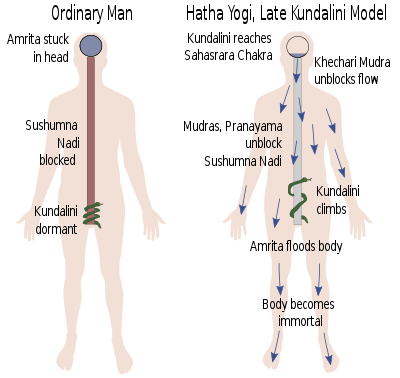

[edit]TheHatha Yoga Pradipikapresents two contradictory models of how Hatha Yoga may lead to immortality (moksha), both culled from other texts, without attempting to harmonise them.[6]

The earlier model involves the manipulation ofBindu;it drips continually from the moon centre in the head, falling to its destruction either in the digestive fire of the belly (the sun centre), or to be ejaculated as semen, with which it was identified. The loss of Bindu causes progressive weakening and ultimately death. In this model, Bindu is to be conserved, and the various mudras act to block its passage down theSushumnanadi, the central channel of thesubtle body.[6]

The later model involves the stimulation ofKundalini,visualised as a small serpent coiled around the base of the Sushumna nadi. In this model, the mudras serve to unblock the channel, allowing Kundalini to rise. When Kundalini finally reaches the top at theSahasrarachakra, the thousand-petalled lotus, the store ofAmrita,the nectar of immortality stored in the head, is released. The Amrita then floods down through the body, rendering it immortal.[6]

Modern research

[edit]TheHatha Yoga Pradipikais the hatha yoga text that has historically been studied withinyoga teacher trainingprogrammes, alongside texts on classical yoga such asPatanjali'sYoga Sutras.[7]In the twenty-first century, research on the history of yoga has led to a more developed understanding of hatha yoga's origins.[8]

James Mallinsonhas studied the origins of hatha yoga in classic yoga texts such as theKhecarīvidyā.He has identified eight works of early hatha yoga that may have contributed to its official formation in theHatha Yoga Pradipika.This has stimulated further research into understanding the formation of hatha yoga.[9]

Jason Birchhas investigated the role of theHatha Yoga Pradīpikāin popularizing an interpretation of the Sanskrit wordhaṭha.The text drew from classic texts on different systems of yoga, and Svātmārāma grouped what he had found under the generic term "haṭha yoga". Examining Buddhist tantric commentaries and earlier medieval yoga texts, Birch found that the adverbial uses of the word suggested that it meant "force", rather than "the metaphysical explanation proposed in the 14th centuryYogabījaof uniting the sun (ha) and moon (ṭha) ".[10]

References

[edit]- ^Master Murugan, Chillayah (20 October 2012)."Veda Studies and Knowledge (Pengetahuan Asas Kitab Veda)".Silambam.Retrieved31 May2013.

- ^Mallinson & Singleton 2017,p. 162.

- ^"Svātmārāma - Collected Information".A Study of the Manuscripts of the Woolner Collection, Lahore.University of Vienna. Archived fromthe originalon 2 June 2016.Retrieved24 March2014.

- ^Pandit, Moti Lal (1991).Towards Transcendence: A Historico-analytical Study of Yoga as a Method of Liberation.Intercultural. p. 205.ISBN978-81-85574-01-1.

- ^Burley, Mikel(2000).Haṭha-Yoga: Its Context, Theory, and Practice.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 6–7.ISBN978-81-208-1706-7.

- ^abcdMallinson & Singleton 2017,pp. 32, 180–181.

- ^Mallinson & Singleton 2017,p. ix.

- ^See, e.g., the work of the members of theModern Yoga Research cooperative

- ^"Dr James Mallinson".Modern Yoga Research.Retrieved17 November2020.

- ^Birch, Jason(2011). "The Meaning of haṭha in Early Haṭhayoga".Journal of the American Oriental Society.131:527–554.JSTOR41440511.

Sources

[edit]- Mallinson, James;Singleton, Mark(2017).Roots of Yoga.Penguin Books.ISBN978-0-241-25304-5.OCLC928480104.

External links

[edit]- Iyangar et al 1972 Translation with Jyotsnā commentary

- Sanskrit text and translation of Pancham Sinh edition at sacred-texts.com

- Hatha Yoga PradipikaPancham Sinh edition from LibriPassArchived25 June 2014 at theWayback Machine

- Sample of new translation by Brian Akers

- 2003 translation with Jyotsnā commentary

- Light on Haṭha Yoga project: a critical edition and translation, 2021