Sugar

Sugaris the generic name forsweet-tasting,solublecarbohydrates,many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also calledmonosaccharides,includeglucose,fructose,andgalactose.Compound sugars, also calleddisaccharidesor double sugars, are molecules made of twobondedmonosaccharides; common examples aresucrose(glucose + fructose),lactose(glucose + galactose), andmaltose(two molecules of glucose).White sugaris a refined form of sucrose. In the body, compound sugars arehydrolysedinto simple sugars.

Longer chains of monosaccharides (>2) are not regarded as sugars and are calledoligosaccharidesorpolysaccharides.Starchis a glucose polymer found in plants, the most abundant source of energy inhuman food.Some other chemical substances, such asethylene glycol,glycerolandsugar alcohols,may have a sweet taste but are not classified as sugar.

Sugars are found in the tissues of most plants.Honeyand fruits are abundant natural sources of simple sugars. Sucrose is especially concentrated insugarcaneandsugar beet,making them ideal for efficient commercialextractionto make refined sugar. In 2016, the combined world production of those two crops was about two billiontonnes.Maltose may be produced bymaltinggrain. Lactose is the only sugar that cannot be extracted from plants. It can only be found in milk, including human breast milk, and in somedairy products.A cheap source of sugar iscorn syrup,industrially produced by convertingcorn starchinto sugars, such as maltose, fructose and glucose.

Sucrose is used in prepared foods (e.g. cookies and cakes), is sometimesaddedto commercially availableultra-processed foodand beverages, and may be used by people as a sweetener for foods (e.g. toast and cereal) and beverages (e.g. coffee and tea). The average person consumes about 24 kilograms (53 pounds) of sugar each year, with North and South Americans consuming up to 50 kg (110 lb) and Africans consuming under 20 kg (44 lb).[1]

Asfree sugarconsumption grew in the latter part of the 20th century, researchers began to examine whether a diet high in free sugar, especially refined sugar, was damaging tohuman health.Excessive consumption of free sugar is associated withobesity,diabetes,cardiovascular disease,cancer andtooth decay.[2]In 2015, theWorld Health Organizationstrongly recommended that adults and children reduce their intake of free sugars to less than 10% of their totalenergy intake,and encouraged a reduction to below 5%.[3]

Etymology

[edit]Theetymologyreflects the spread of the commodity. FromSanskrit(śarkarā), meaning "ground or candied sugar", camePersianshakarand Arabicsukkar.The Arabic word was borrowed in Medieval Latin assuccarum,whence the 12th centuryFrenchsucreand the Englishsugar.Sugar was introduced into Europe by the Arabs in Sicily and Spain.[4]

The English wordjaggery,a coarsebrown sugarmade fromdate palmsap orsugarcanejuice, has a similar etymological origin: Portuguesejágarafrom the Malayalamcakkarā,which is from the Sanskritśarkarā.[5]

History

[edit]Ancient world to Renaissance

[edit]

Asia

[edit]Sugar has been produced in theIndian subcontinent[6]since ancient times and its cultivation spread from there into modern-day Afghanistan through theKhyber Pass.[7]It was not plentiful or cheap in early times, and in most parts of the world,honeywas more often used for sweetening.[8]Originally, people chewed raw sugarcane to extract its sweetness. Even after refined sugarcane became more widely available during the European colonial era,[9]palm sugarwas preferred inJavaand other sugar producing parts of southeast Asia, and along withcoconut sugar,is still used locally to make desserts today.[10][11]

Sugarcane is native of tropical areas such as the Indian subcontinent (South Asia) and Southeast Asia.[6][12]Different species seem to have originated from different locations withSaccharum barberioriginating in India andS. eduleandS. officinarumcoming fromNew Guinea.[12][13]One of the earliest historical references to sugarcane is in Chinese manuscripts dating to 8th century BCE, which state that the use of sugarcane originated in India.[14]

In the tradition of Indian medicine (āyurveda), the sugarcane is known by the nameIkṣuand the sugarcane juice is known asPhāṇita.Its varieties, synonyms and characteristics are defined innighaṇṭussuch as the Bhāvaprakāśa (1.6.23, group of sugarcanes).[15]

Sugar remained relatively unimportant until the Indians discovered methods of turningsugarcane juiceinto granulated crystals that were easier to store and to transport.[16]A process the Greek physicianPedanius Dioscoridesattested to in his 1st century CE medical treatiseDe Materia Medica:

There is a kind of coalesced honey called sakcharon [i.e. sugar] found in reeds in India andEudaimon Arabiasimilar in consistency to salt and brittle enough to be broken between the teeth like salt,

In the local Indian language, these crystals were calledkhanda(Devanagari:खण्ड,Khaṇḍa), which is the source of the wordcandy.[19]Indian sailors, who carriedclarified butterand sugar as supplies, introduced knowledge of sugar along the varioustrade routesthey travelled.[16]Traveling Buddhist monks took sugarcrystallization methodsto China.[20]During the reign ofHarsha(r. 606–647) inNorth India,Indian envoys inTang Chinataught methods of cultivating sugarcane afterEmperor Taizong of Tang(r. 626–649) made known his interest in sugar. China established its first sugarcane plantations in the seventh century.[21]Chinese documents confirm at least two missions to India, initiated in 647 CE, to obtain technology for sugar refining.[22]In the Indian subcontinent,[6]the Middle East and China, sugar became a staple of cooking and desserts.

Europe

[edit]

Nearchus,admiral ofAlexander the Great,knew of sugar during the year 325 BC, because of his participation inthe campaign of Indialed by Alexander (Arrian,Anabasis).[23][24]In addition to the Greek physicianPedanius Dioscorides,the RomanPliny the Elderalso described sugar in his 1st century CENatural History:"Sugar is made in Arabia as well, but Indian sugar is better. It is a kind of honey found in cane, white as gum, and it crunches between the teeth. It comes in lumps the size of a hazelnut. Sugar is used only for medical purposes."[25]Crusadersbrought sugar back to Europe after their campaigns in theHoly Land,where they encountered caravans carrying "sweet salt". Early in the 12th century, Venice acquired some villages nearTyreand set up estates to produce sugar for export to Europe. It supplemented the use of honey, which had previously been the only available sweetener.[26]Crusade chroniclerWilliam of Tyre,writing in the late 12th century, described sugar as "very necessary for the use and health of mankind".[27]In the 15th century,Venicewas the chief sugar refining and distribution center in Europe.[14]

There was a drastic change in the mid-15th century, whenMadeiraand theCanary Islandswere settled from Europe and sugar introduced there.[28][29]After this an "all-consuming passion for sugar... swept through society" as it became far more easily available, though initially still very expensive.[30]By 1492, Madeira was producing over 1,400,000 kilograms (3,000,000 lb) of sugar annually.[31]Genoa,one of the centers of distribution, became known for candied fruit, while Venice specialized in pastries, sweets (candies), andsugar sculptures.Sugar was considered to have "valuable medicinal properties" as a "warm" food under prevailing categories, being "helpful to the stomach, to cure cold diseases, and sooth lung complaints".[32]

A feast given inToursin 1457 byGaston de Foix,which is "probably the best and most complete account we have of a late medieval banquet" includes the first mention of sugar sculptures, as the final food brought in was "a heraldic menagerie sculpted in sugar: lions, stags, monkeys... each holding in paw or beak the arms of the Hungarian king".[33]Other recorded grand feasts in the decades following included similar pieces.[34]Originally the sculptures seem to have been eaten in the meal, but later they become merely table decorations, the most elaborate calledtrionfi.Several significant sculptors are known to have produced them; in some cases their preliminary drawings survive. Early ones were in brown sugar, partlycastin molds, with the final touches carved. They continued to be used until at least the Coronation Banquet forEdward VII of the United Kingdomin 1903; among other sculptures every guest was given a sugar crown to take away.[35]

Modern history

[edit]In August 1492,Christopher Columbuscollected sugar cane samples inLa Gomerain theCanary Islands,and introduced it to the New World.[36]The cuttings were planted and the first sugar-cane harvest inHispaniolatook place in 1501. Many sugar mills had been constructed inCubaandJamaicaby the 1520s.[37]The Portuguese took sugar cane to Brazil. By 1540, there were 800 cane-sugar mills inSanta Catarina Islandand another 2,000 on the north coast of Brazil,Demarara,andSurinam.It took until 1600 for Brazilian sugar production to exceed that ofSão Tomé,which was the main center of sugar production in sixteenth century.[29]

Sugar was a luxury in Europe until the early 19th century, when it became more widely available, due to the rise ofbeet sugarinPrussia,and later inFranceunderNapoleon.[38]Beet sugar was a German invention, since, in 1747,Andreas Sigismund Marggrafannounced the discovery of sugar in beets and devised a method using alcohol to extract it.[39]Marggraf's student,Franz Karl Achard,devised an economical industrial method to extract the sugar in its pure form in the late 18th century.[40][41]Achard first produced beet sugar in 1783 inKaulsdorf,and in 1801, the world's first beet sugar production facility was established inCunern,Silesia(then part of Prussia, nowPoland).[42]The works of Marggraf and Achard were the starting point for the sugar industry in Europe,[43]and for the modern sugar industry in general, since sugar was no longer a luxury product and a product almost only produced in warmer climates.[44]

Sugar became highly popular and by the 19th century, was found in every household. This evolution of taste and demand for sugar as an essential food ingredient resulted in major economic and social changes.[45]Demand drove, in part, the colonization of tropical islands and areas where labor-intensive sugarcane plantations and sugar manufacturing facilities could be successful.[45]World consumption increased more than 100 times from 1850 to 2000, led by Britain, where it increased from about 2 pounds per head per year in 1650 to 90 pounds by the early 20th century. In the late 18th century Britain consumed about half the sugar which reached Europe.[46]

After slavery wasabolished,the demand for workers in European colonies in the Caribbean was filled byindentured laborersfrom theIndian subcontinent.[47][48][49]Millions of enslaved or indentured laborers were brought to various European colonies in the Americas, Africa and Asia (as a result of demand in Europe for among other commodities, sugar), influencing the ethnic mixture of numerous nations around the globe.[50][51][52]

Sugar also led to some industrialization of areas where sugar cane was grown. For example, in the 1790s Lieutenant J. Paterson, of theBengal Presidencypromoted to theBritish parliamentthe idea that sugar cane could grow inBritish India,where it had started, with many advantages and at less expense than in the West Indies. As a result, sugar factories were established inBiharin eastern India.[53][54] During theNapoleonic Wars,sugar-beet production increased in continental Europe because of the difficulty of importing sugar when shipping was subject toblockade.By 1880 the sugar beet was the main source of sugar in Europe. It was also cultivated inLincolnshireand other parts of England, although the United Kingdom continued to import the main part of its sugar from its colonies.[55]

Until the late nineteenth century, sugar was purchased inloaves,which had to be cut using implements calledsugar nips.[56]In later years, granulated sugar was more usually sold in bags.Sugar cubeswere produced in the nineteenth century. The first inventor of a process to produce sugar in cube form wasJakob Christof Rad,director of a sugar refinery inDačice.In 1841, he produced the first sugar cube in the world.[57]He began sugar-cube production after being granted a five-year patent for the process on 23 January 1843.Henry TateofTate & Lylewas another early manufacturer of sugar cubes at his refineries inLiverpooland London. Tate purchased a patent for sugar-cube manufacture from GermanEugen Langen,who in 1872 had invented a different method of processing of sugar cubes.[58]

Sugar was rationed during World War I, though it was said that "No previous war in history has been fought so largely on sugar and so little on alcohol",[59]and more sharply during World War II.[60][61][62][63][64]Rationing led to the development and use of variousartificial sweeteners.[60][65]

Chemistry

[edit]

Scientifically,sugarloosely refers to a number ofcarbohydrates,such asmonosaccharides,disaccharides,oroligosaccharides.Monosaccharides are also called "simple sugars", the most important being glucose. Most monosaccharides have a formula that conforms toC

nH

2nO

nwith n between 3 and 7 (deoxyribosebeing an exception).Glucosehas themolecular formulaC

6H

12O

6.The names of typical sugars end with -ose,as in "glucose" and "fructose".Sometimes such words may also refer to any types ofcarbohydratessoluble in water. Theacyclicmono- and disaccharides contain eitheraldehydegroups orketonegroups. Thesecarbon-oxygendouble bonds (C=O) are the reactive centers. Allsaccharideswith more than one ring in their structure result from two or more monosaccharides joined byglycosidic bondswith the resultant loss of a molecule of water (H

2O) per bond.[66]

Monosaccharidesin a closed-chain form can form glycosidic bonds with other monosaccharides, creating disaccharides (such assucrose) andpolysaccharides(such asstarchorcellulose).Enzymesmust hydrolyze or otherwise break these glycosidic bonds before such compounds becomemetabolized.After digestion and absorption the principal monosaccharides present in the blood and internal tissues include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Manypentosesandhexosescan formring structures.In these closed-chain forms, the aldehyde or ketone group remains non-free, so many of the reactions typical of these groups cannot occur. Glucose in solution exists mostly in the ring form atequilibrium,with less than 0.1% of the molecules in the open-chain form.[66]

Natural polymers

[edit]Biopolymersof sugars are common in nature. Through photosynthesis, plants produceglyceraldehyde-3-phosphate(G3P), a phosphated 3-carbon sugar that is used by the cell to make monosaccharides such as glucose (C

6H

12O

6) or (as in cane and beet) sucrose (C

12H

22O

11). Monosaccharides may be further converted intostructural polysaccharidessuch ascelluloseandpectinforcell wallconstruction or into energy reserves in the form ofstorage polysaccharidessuch as starch orinulin.Starch, consisting of two different polymers of glucose, is a readily degradable form of chemicalenergystored bycells,and can be converted to other types of energy.[66]Another polymer of glucose is cellulose, which is a linear chain composed of several hundred or thousand glucose units. It is used by plants as a structural component in their cell walls. Humans can digest cellulose only to a very limited extent, thoughruminantscan do so with the help ofsymbioticbacteria in their gut.[67]DNAandRNAare built up of the monosaccharidesdeoxyriboseandribose,respectively. Deoxyribose has the formulaC

5H

10O

4and ribose the formulaC

5H

10O

5.[68]

Flammability and heat response

[edit]

Because sugars burn easily when exposed to flame, the handling of sugars risksdust explosion.The risk of explosion is higher when the sugar has been milled to superfine texture, such as for use inchewing gum.[69]The2008 Georgia sugar refinery explosion,which killed 14 people and injured 36, and destroyed most of the refinery, was caused by the ignition of sugar dust.[70]

In its culinary use, exposing sugar to heat causescaramelization.As the process occurs,volatilechemicals such asdiacetylare released, producing the characteristiccaramelflavor.[71]

Types

[edit]Monosaccharides

[edit]Fructose, galactose, and glucose are all simple sugars, monosaccharides, with the general formula C6H12O6.They have five hydroxyl groups (−OH) and a carbonyl group (C=O) and are cyclic when dissolved in water. They each exist as severalisomerswith dextro- and laevo-rotatory forms that cause polarized light to diverge to the right or the left.[72]

- Fructose,or fruit sugar, occurs naturally in fruits, some root vegetables, cane sugar and honey and is the sweetest of the sugars. It is one of the components of sucrose or table sugar. It is used as ahigh-fructose syrup,which is manufactured from hydrolyzed corn starch that has been processed to yieldcorn syrup,with enzymes then added to convert part of the glucose into fructose.[73]

- Galactosegenerally does not occur in the free state but is a constituent with glucose of the disaccharidelactoseor milk sugar. It is less sweet than glucose. It is a component of the antigens found on the surface ofred blood cellsthat determineblood groups.[74]

- Glucoseoccurs naturally in fruits and plant juices and is the primary product ofphotosynthesis.Starchis converted into glucose during digestion, and glucose is the form of sugar that is transported around the bodies of animals in the bloodstream. Although in principle there are twoenantiomersof glucose (mirror images one of the other), naturally occurring glucose is D-glucose. This is also calleddextrose,orgrape sugarbecause drying grape juice produces crystals of dextrose that can besievedfrom the other components.[75]Glucose syrup is a liquid form of glucose that is widely used in the manufacture of foodstuffs. It can be manufactured from starch byenzymatic hydrolysis.[76]For example,corn syrup,which is produced commercially by breaking downmaize starch,is one common source of purified dextrose.[77]However, dextrose is naturally present in many unprocessed,whole foods,includinghoneyand fruits such as grapes.[78]

Disaccharides

[edit]Lactose, maltose, and sucrose are all compound sugars, disaccharides, with the general formula C12H22O11.They are formed by the combination of two monosaccharide molecules with the exclusion of a molecule of water.[72]

- Lactoseis the naturally occurring sugar found in milk. A molecule of lactose is formed by the combination of a molecule of galactose with a molecule of glucose. It is broken down when consumed into its constituent parts by the enzymelactaseduring digestion. Children have this enzyme but some adults no longer form it and they are unable to digest lactose.[79]

- Maltoseis formed during the germination of certain grains, the most notable beingbarley,which is converted intomalt,the source of the sugar's name. A molecule of maltose is formed by the combination of two molecules of glucose. It is less sweet than glucose, fructose or sucrose.[72]It is formed in the body during the digestion of starch by the enzymeamylaseand is itself broken down during digestion by the enzymemaltase.[80]

- Sucroseis found in the stems of sugarcane and roots of sugar beet. It also occurs naturally alongside fructose and glucose in other plants, in particular fruits and some roots such as carrots. The different proportions of sugars found in these foods determines the range of sweetness experienced when eating them.[72]A molecule of sucrose is formed by the combination of a molecule of glucose with a molecule of fructose. After being eaten, sucrose is split into its constituent parts during digestion by a number of enzymes known assucrases.[81]

Sources

[edit]The sugar contents of common fruits and vegetables are presented in Table 1.

| Food item | Total carbohydrateA including dietary fiber |

Total sugars |

Free fructose |

Free glucose |

Sucrose | Fructose/ (Fructose+Glucose) ratioB |

Sucrose as a % of total sugars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | |||||||

| Apple | 13.8 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0.67 | 20 |

| Apricot | 11.1 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 0.42 | 64 |

| Banana | 22.8 | 12.2 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 20 |

| Fig,dried | 63.9 | 47.9 | 22.9 | 24.8 | 0.9 | 0.48 | 1.9 |

| Grapes | 18.1 | 15.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 0.2 | 0.53 | 1 |

| Navel orange | 12.5 | 8.5 | 2.25 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 0.51 | 51 |

| Peach | 9.5 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 0.47 | 57 |

| Pear | 15.5 | 9.8 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.67 | 8 |

| Pineapple | 13.1 | 9.9 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 0.52 | 61 |

| Plum | 11.4 | 9.9 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 0.40 | 16 |

| Strawberry | 7.68 | 4.89 | 2.441 | 1.99 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 10 |

| Vegetables | |||||||

| Beet,red | 9.6 | 6.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 0.50 | 96 |

| Carrot | 9.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 0.50 | 77 |

| Corn, sweet | 19.0 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.38 | 15 |

| Red pepper,sweet | 6.0 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.55 | 0 |

| Onion, sweet | 7.6 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.47 | 14 |

| Sweet potato | 20.1 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.47 | 60 |

| Yam | 27.9 | 0.5 | tr | tr | tr | na | tr |

| Sugar cane | 13–18 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.2–1.0 | 11–16 | 0.50 | high | |

| Sugar beet | 17–18 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.1–0.5 | 16–17 | 0.50 | high |

- ^AThe carbohydrate figure is calculated in the USDA database and does not always correspond to the sum of the sugars, the starch, and the dietary fiber.[why?]

- ^BThe fructose to fructose plus glucose ratio is calculated by including the fructose and glucose coming from the sucrose.

Production

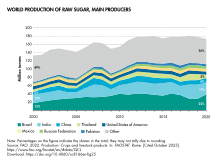

[edit]Due to rising demand, sugar production in general increased some 14% over the period 2009 to 2018.[83]The largest importers were China,Indonesia,and the United States.[83]

Sugarcane

[edit]| Sugarcane production – 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Millions oftonnes |

| 757.1 | |

| 370.5 | |

| 108.1 | |

| 75.0 | |

| World | 1,870 |

| Source:FAOSTAT,United Nations[84] | |

Sugar cane accounted for around 21% of the global crop production over the 2000–2021 period. The Americas was the leading region in the production of sugar cane (52% of the world total).[85]

Global production ofsugarcanein 2020 was 1.9 billion tonnes, with Brazil producing 40% of the world total and India 20% (table).

Sugarcane refers to any of several species, or their hybrids, of giant grasses in the genusSaccharumin the familyPoaceae.They have been cultivated in tropical climates in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia over centuries for the sucrose found in their stems.[6]A great expansion in sugarcane production took place in the 18th century with the establishment ofslave plantationsin the Americas. The use ofslaveryfor the labor-intensive process resulted in sugar production, enabling prices cheap enough for most people to buy. Mechanization reduced some labor needs, but in the 21st century, cultivation and production relied on low-wage laborers.

Sugar cane requires a frost-free climate with sufficient rainfall during the growing season to make full use of the plant's substantial growth potential. The crop is harvested mechanically or by hand, chopped into lengths and conveyed rapidly to theprocessing plant(commonly known as asugar mill) where it is either milled and the juice extracted with water or extracted by diffusion.[87]The juice is clarified withlimeand heated to destroyenzymes.The resulting thin syrup is concentrated in a series of evaporators, after which further water is removed. The resultingsupersaturatedsolution is seeded with sugar crystals, facilitating crystal formation and drying.[87]Molassesis a by-product of the process and the fiber from the stems, known asbagasse,[87]is burned to provide energy for the sugar extraction process. The crystals of raw sugar have a sticky brown coating and either can be used as they are, can be bleached bysulfur dioxide,or can be treated in acarbonatationprocess to produce a whiter product.[87]About 2,500 litres (660 US gal) of irrigation water is needed for every one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of sugar produced.[88]

Sugar beet

[edit]| Sugar beet production – 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Millions oftonnes |

| Russia | 33.9 |

| United States | 30.5 |

| Germany | 28.6 |

| France | 26.2 |

| World | 253 |

| Source:FAOSTAT,United Nations[89] | |

In 2020, global production ofsugar beetswas 253 milliontonnes,led by Russia with 13% of the world total (table).

The sugar beet became a major source of sugar in the 19th century when methods for extracting the sugar became available. It is abiennial plant,[90]acultivated varietyofBeta vulgarisin thefamilyAmaranthaceae,the tuberous root of which contains a high proportion of sucrose. It is cultivated as a root crop in temperate regions with adequate rainfall and requires a fertile soil. The crop is harvested mechanically in the autumn and the crown of leaves and excess soil removed. The roots do not deteriorate rapidly and may be left in the field for some weeks before being transported to the processing plant where the crop is washed and sliced, and the sugar extracted by diffusion.[91]Milk of limeis added to the raw juice withcalcium carbonate.After water is evaporated by boiling the syrup under a vacuum, the syrup is cooled and seeded with sugar crystals. Thewhite sugarthat crystallizes can be separated in a centrifuge and dried, requiring no further refining.[91]

Refining

[edit]Refined sugar is made from raw sugar that has undergone arefiningprocess to remove themolasses.[92][93]Raw sugar is sucrose which is extracted from sugarcane orsugar beet.While raw sugar can be consumed, the refining process removes unwanted tastes and results in refined sugar or white sugar.[94][95]

The sugar may be transported in bulk to the country where it will be used and the refining process often takes place there. The first stage is known as affination and involves immersing the sugar crystals in a concentrated syrup that softens and removes the sticky brown coating without dissolving them. The crystals are then separated from the liquor and dissolved in water. The resulting syrup is treated either by acarbonatationor by a phosphatation process. Both involve the precipitation of a fine solid in the syrup and when this is filtered out, many of the impurities are removed at the same time. Removal of color is achieved by using either a granularactivated carbonor anion-exchange resin.The sugar syrup is concentrated by boiling and then cooled and seeded with sugar crystals, causing the sugar to crystallize out. The liquor is spun off in a centrifuge and the white crystals are dried in hot air and ready to be packaged or used. The surplus liquor is made into refiners' molasses.[96]

TheInternational Commission for Uniform Methods of Sugar Analysissets standards for the measurement of the purity of refined sugar, known as ICUMSA numbers; lower numbers indicate a higher level of purity in the refined sugar.[97]

Refined sugar is widely used for industrial needs for higher quality. Refined sugar is purer (ICUMSA below 300) than raw sugar (ICUMSA over 1,500).[98]The level of purity associated with the colors of sugar, expressed by standard numberICUMSA,the smaller ICUMSA numbers indicate the higher purity of sugar.[98]

Forms and uses

[edit]Crystal size

[edit]- Coarse-grain sugar,also known as sanding sugar, composed of reflective crystals with grain size of about 1 to 3 mm, similar tokitchen salt.Used atop baked products and candies, it will not dissolve when subjected to heat and moisture.[99]

- Granulated sugar (about 0.6 mm crystals), also known as table sugar or regular sugar, is used at the table, to sprinkle on foods and to sweeten hot drinks (coffee and tea), and in home baking to add sweetness and texture to baked products (cookies and cakes) and desserts (pudding and ice cream). It is also used as a preservative to prevent micro-organisms from growing and perishable food from spoiling, as in candied fruits, jams, andmarmalades.[100]

- Milled sugars are ground to a fine powder. They are used for dusting foods and in baking and confectionery.[101][99]

- Caster sugar,sold as "superfine" sugar in the United States, with grain size of about 0.35 mm

- Powdered sugar,also known as confectioner's sugar or icing sugar, available in varying degrees of fineness (e.g., fine powdered or 3X, very fine or 6X, and ultra-fine or 10X). The ultra-fine variety (sometimes called 10X) has grain size of about 0.060 mm, that is about ten times smaller than granulated sugar.

- Snow powder,a non-melting form of powdered sugar usually consisting of glucose, rather than sucrose.

- Screened sugars are crystalline products separated according to the size of the grains. They are used for decorative table sugars, for blending in dry mixes and in baking and confectionery.[101]

Shapes

[edit]

- Cube sugar(sometimes called sugar lumps) are white or brown granulated sugars lightly steamed and pressed together in block shape. They are used to sweeten drinks.[101]

- Sugarloafwas the usualcone-form in which refined sugar was produced and sold until the late 19th century. This shape is still in use in Germany (for preparation ofFeuerzangenbowle) as well asIranandMorocco.

Brown sugars

[edit]

Brown sugarsare granulated sugars, either containing residual molasses, or with the grains deliberately coated with molasses to produce a light- or dark-colored sugar. They are used in baked goods, confectionery, andtoffees.[101]Their darkness is due to the amount of molasses they contain. They may be classified based on their darkness or country of origin. For instance:[99]

- Light brown, with little content of molasses (about 3.5%)

- Dark brown, with higher content of molasses (about 6.5%)

- Non-centrifugal cane sugar,unrefined and hence very dark cane sugar obtained by evaporating water from sugarcane juice, such as:

- Panela,also known as rapadura, chancaca, piloncillo.

- Some varieties ofmuscovado,also known as Barbados sugar. Other varieties are partially refined by centrifugation or by using aspray dryer.

- Some varieties ofjaggery.Other varieties are produced fromdate fruitsor frompalmsap,rather than sugarcane juice.

Liquid sugars

[edit]

- Honey,mainly containing unbound molecules of fructose and glucose, is a viscous liquid produced by bees by digesting floralnectar.

- Honeydewis a sugar-rich sticky liquid, secreted by aphids, some scale insects, and many other true bugs and some other insects as they feed on plant sap.

- Syrupsare thick, viscous liquids consisting primarily of a solution of sugar in water. They are used in the food processing of a wide range of products including beverages,hard candy,ice cream,andjams.[101]

- Syrups made by dissolving granulated sugar in water are sometimes referred to as liquid sugar. A liquid sugar containing 50% sugar and 50% water is called simple syrup.

- Syrups can also be made byreducingnaturally sweet juices such ascanejuice, ormaplesap.

- Corn syrupis made by convertingcorn starchto sugars (mainly maltose and glucose).

- High-fructose corn syrup(HFCS), is produced by further processing corn syrup to convert some of its glucose into fructose.

- Inverted sugar syrup,commonly known as invert syrup or invert sugar, is a mixture of two simple sugars—glucose and fructose—that is made by heating granulated sugar in water. It is used in breads, cakes, and beverages for adjusting sweetness, aiding moisture retention and avoiding crystallization of sugars.[101]

- Molassesandtreacleare obtained by removing sugar from sugarcane or sugar beet juice, as a byproduct of sugar production. They may be blended with the above-mentioned syrups to enhance sweetness and used in a range of baked goods and confectionery including toffees andlicorice.[101]

- Blackstrap molasses, also known as black treacle, has dark color, relatively small sugar content and strong flavour. It is sometimes added to animal feed, or processed to producerum,orethanolfor fuel.

- Regular molasses andgolden syruptreacle have higher sugar content and lighter color, relative to blackstrap.

- Inwinemaking,fruit sugarsare converted into alcohol by afermentationprocess. If themustformed by pressing the fruit has a low sugar content, additional sugar may be added to raise the alcohol content of the wine in a process calledchaptalization.In the production of sweet wines, fermentation may be halted before it has run its full course, leaving behind someresidual sugarthat gives the wine its sweet taste.[102]

Other sweeteners

[edit]- Low-calorie sweeteners are often made ofmaltodextrinwith added sweeteners. Maltodextrin is an easily digestible syntheticpolysaccharideconsisting of short chains of three or more glucose molecules and is made by the partialhydrolysisof starch.[103]Strictly, maltodextrin is not classified as sugar as it contains more than two glucose molecules, although its structure is similar tomaltose,a molecule composed of two joined glucose molecules.

- Polyolsaresugar alcoholsand are used in chewing gums where a sweet flavor is required that lasts for a prolonged time in the mouth.[104]

- Several different kinds of zero-calorieartificial sweetenersmay be also used as sugar substitutes.

Consumption

[edit]Worldwide sugar provides 10% of the daily calories (based on an 2000 kcal diet).[105]In 1750 the average Briton got 72 calories a day from sugar. In 1913 this had risen to 395. In 2015 it still provided around 14% of the calories in British diets.[106]According to one source, per capita consumption of sugar in 2016 was highest in the United States, followed by Germany and the Netherlands.[107]

Nutrition and flavor

[edit]| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,576 kJ (377 kcal) |

97.33 g | |

| Sugars | 96.21 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0 g |

0 g | |

0 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 1% 0.008 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 1% 0.007 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 1% 0.082 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 2% 0.026 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 0% 1 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 7% 85 mg |

| Iron | 11% 1.91 mg |

| Magnesium | 7% 29 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 22 mg |

| Potassium | 4% 133 mg |

| Sodium | 2% 39 mg |

| Zinc | 2% 0.18 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 1.77 g |

| †Percentages estimated usingUS recommendationsfor adults,[108]except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation fromthe National Academies.[109] | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,619 kJ (387 kcal) |

99.98 g | |

| Sugars | 99.91 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0 g |

0 g | |

0 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 1% 0.019 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 0% 1 mg |

| Iron | 0% 0.01 mg |

| Potassium | 0% 2 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 0.03 g |

| †Percentages estimated usingUS recommendationsfor adults,[108]except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation fromthe National Academies.[109] | |

Brown and white granulated sugar are 97% to nearly 100% carbohydrates, respectively, with less than 2% water, and no dietary fiber, protein or fat (table). Brown sugar contains a moderate amount of iron (15% of theReference Daily Intakein a 100 gram amount, see table), but a typical serving of 4 grams (one teaspoon), would provide 15caloriesand a negligible amount of iron or any other nutrient.[110]Because brown sugar contains 5–10%molassesreintroduced during processing, its value to some consumers is a richer flavor than white sugar.[111]

Health effects

[edit]Sugar industry funding and health information

[edit]Sugar refiners and manufacturers of sugary foods and drinks have sought to influence medical research andpublic healthrecommendations,[112][113]with substantial and largely clandestine spending documented from the 1960s to 2016.[114][115][116][117]The results of research on the health effects of sugary food and drink differ significantly, depending on whether the researcher has financial ties to the food and drink industry.[118][119][120]A 2013 medical review concluded that "unhealthy commodity industries should have no role in the formation of national or international NCD [non-communicable disease] policy ".[121]

There have been similar efforts to steer coverage of sugar-related health information in popular media, including news media and social media.[122][123][124]

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

[edit]A 2003 technical report by theWorld Health Organization(WHO) provides evidence that high intake of sugary drinks (includingfruit juice) increases the risk ofobesityby adding to overallenergy intake.[125]By itself, sugar is not a factor causing obesity andmetabolic syndrome,but rather – when over-consumed – is a component of unhealthy dietary behavior.[125][needs update]Meta-analysesshowed that excessive consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages increased the risk of developingtype 2 diabetesandmetabolic syndrome– including weight gain[126]and obesity – in adults and children.[127][128]

Cancer

[edit]Sugar consumption does not cause cancer.[129][130][131]Cancer Council Australiahave stated that "there is no evidence that consuming sugar makes cancer cells grow faster or cause cancer".[129]There is an indirect relationship between sugar consumption and obesity-related cancers through increased risk of excess body weight.[131][129][132]

TheAmerican Institute for Cancer ResearchandWorld Cancer Research Fundrecommend that people limit sugar consumption.[133][134]

Cognition

[edit]Despite some studies suggesting that sugar consumption causes hyperactivity, the quality of evidence is low[135]and it is generally accepted within the scientific community that the notion of children's 'sugar rush' is a myth.[136][137]A 2019meta-analysisfound that sugar consumption does not improvemood,but can lower alertness and increase fatigue within an hour of consumption.[138]One review of low-quality studies of children consuming high amounts ofenergy drinksshowed association with higher rates of unhealthy behaviors, including smoking and excessive alcohol use, and with hyperactivity andinsomnia,although such effects could not be specifically attributed to sugar over other components of those drinks such ascaffeine.[139]

Tooth decay

[edit]The 2003 WHO report stated that "Sugars are undoubtedly the most important dietary factor in the development ofdental caries".[125]A review of human studies showed that the incidence of caries is lower when sugar intake is less than 10% of total energy consumed.[140]

Nutritional displacement

[edit]The "empty calories"argument states that a diet high inadded(or 'free') sugars will reduce consumption of foods that containessential nutrients.[141]This nutrient displacement occurs if sugar makes up more than 25% of daily energy intake,[142]a proportion associated with poor diet quality and risk of obesity.[143]Displacement may occur at lower levels of consumption.[142]

Recommended dietary intake

[edit]The WHO recommends that both adults and children reduce the intake of free sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake, and suggests a reduction to below 5%. "Free sugars" include monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods, and sugars found in fruit juice and concentrates, as well as in honey and syrups. According to the WHO, "[t]hese recommendations were based on the totality of available evidence reviewed regarding the relationship between free sugars intake and body weight (low and moderate quality evidence) and dental caries (very low and moderate quality evidence)."[3]

On 20 May 2016, the U.S.Food and Drug Administrationannounced changes to the Nutrition Facts panel displayed on all foods, to be effective by July 2018. New to the panel is a requirement to list "added sugars" by weight and as a percent of Daily Value (DV). For vitamins and minerals, the intent of DVs is to indicate how much should be consumed. For added sugars, the guidance is that 100% DV should not be exceeded. 100% DV is defined as 50 grams. For a person consuming 2000 calories a day, 50 grams is equal to 200 calories and thus 10% of total calories—the same guidance as the WHO.[144]To put this in context, most 12-US-fluid-ounce (355 ml) cans of soda contain 39 grams of sugar. In the United States, a government survey on food consumption in 2013–2014 reported that, for men and women aged 20 and older, the average total sugar intakes—naturally occurring in foods and added—were, respectively, 125 and 99 g/day.[145]

Measurements

[edit]Various culinary sugars have different densities due to differences in particle size and inclusion of moisture.

Domino Sugargives the following weight to volume conversions (inUnited States customary units):[146]

- Firmly packed brown sugar 1 lb = 2.5 cups (or 1.3 L per kg, 0.77 kg/L)

- Granulated sugar 1 lb = 2.25 cups (or 1.17 L per kg, 0.85 kg/L)

- Unsifted confectioner's sugar 1 lb = 3.75 cups (or 2.0 L per kg, 0.5 kg/L)

The "Engineering Resources – Bulk Density Chart" published inPowder and Bulkgives different values for the bulk densities:[147]

- Beet sugar 0.80 g/mL

- Dextrose sugar 0.62 g/mL ( = 620 kg/m^3)

- Granulated sugar 0.70 g/mL

- Powdered sugar 0.56 g/mL

Society and culture

[edit]Manufacturers of sugary products, such as soft drinks and candy, and theSugar Research Foundationhave been accused of trying to influence consumers and medical associations in the 1960s and 1970s by creating doubt about the potential health hazards of sucrose overconsumption, while promotingsaturated fatas the main dietary risk factor incardiovascular diseases.[114]In 2016, the criticism led to recommendations that dietpolicymakersemphasize the need for high-quality research that accounts for multiplebiomarkerson development of cardiovascular diseases.[114]

Gallery

[edit]-

Brown sugar crystals

-

Wholedatesugar

-

Wholecanesugar (grey),vacuum-dried

-

Whole cane sugar (brown), vacuum-dried

-

Raw crystals of unrefined, unbleached sugar

See also

[edit]- Barley sugar

- Holing cane

- List of unrefined sweeteners

- Rare sugar

- Carbonated drinks

- Sugar plantations in the Caribbean

- Glycomics

References

[edit]- ^"OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2020–2029 – Sugar"(PDF).Food and Agriculture Organization.2019.Archived(PDF)from the original on 17 April 2021.Retrieved15 February2021.

- ^Huang, Yin; Chen, Zeyu; Chen, Bo; Li, Jinze; Yuan, Xiang; Li, Jin; Wang, Wen; Dai, Tingting; Chen, Hongying; Wang, Yan; Wang, Ruyi; Wang, Puze; Guo, Jianbing; Dong, Qiang; Liu, Chengfei (5 April 2023)."Dietary sugar consumption and health: umbrella review".BMJ.381:e071609.doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071609.ISSN1756-1833.PMC10074550.PMID37019448.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2023.Retrieved27 April2023.

- ^ab"Guideline: Sugar intake for adults and children"(PDF).Geneva: World Health Organization. 2015. p. 4.Archived(PDF)from the original on 4 July 2018.

- ^Harper, Douglas."Sugar".Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^"Jaggery".Oxford Dictionaries. Archived fromthe originalon 1 October 2012.Retrieved17 August2012.

- ^abcdRoy Moxham (7 February 2002).The Great Hedge of India: The Search for the Living Barrier that Divided a People.Basic Books.ISBN978-0-7867-0976-2.

- ^Gordon, Stewart (2008).When Asia was the World.Da Capo Press. p. 12.

- ^Eteraf-Oskouei, Tahereh; Najafi, Moslem (June 2013)."Traditional and Modern Uses of Natural Honey in Human Diseases: A Review".Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences.16(6): 731–742.PMC3758027.PMID23997898.

- ^The Cambridge World History of Food.Cambridge University Press. 2000. p. 1162.ISBN9780521402156.Archivedfrom the original on 15 April 2023.Retrieved19 March2023.

- ^Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia from Angor Wat to East Timor.ABC-CLIO. 2004. p. 1257.ISBN9781576077702.Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2023.Retrieved19 March2023.

- ^Cooking Through History: A Worldwide Encyclopedia of Food with Menus and Recipes.ABC-CLIO. 2 December 2020. p. 645.ISBN9781610694568.Archivedfrom the original on 15 April 2023.Retrieved19 March2023.

- ^abKiple, Kenneth F. & Kriemhild Conee Ornelas.World history of Food – Sugar.Cambridge University Press.Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2012.Retrieved9 January2012.

- ^Sharpe, Peter (1998)."Sugar Cane: Past and Present".Illinois: Southern Illinois University.Archived fromthe originalon 10 July 2011.

- ^abRolph, George (1873).Something about sugar: its history, growth, manufacture and distribution.San Francisco: J.J. Newbegin.

- ^Murthy, K.R. Srikantha (2016).Bhāvaprakāśa of Bhāvamiśra, Vol. I.Krishnadas Ayurveda Series 45 (reprint 2016 ed.). Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy, Varanasi. pp. 490–94.ISBN978-81-218-0000-6.

- ^abAdas, Michael (January 2001).Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History.Temple University Press.ISBN1-56639-832-0.p. 311.

- ^Quoted from Book Two of Dioscorides'Materia Medica.The book is downloadable from links at the WikipediaDioscoridespage.

- ^de materia medica.

- ^"Sugarcane: Saccharum Officinarum"(PDF).USAID, Govt of United States. 2006. p. 7.1. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 6 November 2013.

- ^Kieschnick, John (2003).The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material CulturePrinceton University Press.ISBN0-691-09676-7.

- ^Sen, Tansen. (2003).Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600–1400.Manoa: Asian Interactions and Comparisons, a joint publication of the University of Hawaii Press and the Association for Asian Studies.ISBN0-8248-2593-4.pp. 38–40.

- ^Kieschnick, John (2003).The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material CulturePrinceton University Press.258.ISBN0-691-09676-7.

- ^Jean Meyer, Histoire du sucre, ed. Desjonquières, 1989

- ^Anabasis Alexandri, translated by E.J. Chinnock (1893)

- ^Faas, Patrick, (2003).Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient RomeArchived31 December 2022 at theWayback Machine.Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 149.ISBN0-226-23347-2

- ^Ponting, Clive(2000) [2000].World history: a new perspective.London: Chatto & Windus. p. 481.ISBN978-0-7011-6834-6.

- ^Barber, Malcolm (2004).The two cities: medieval Europe, 1050–1320(2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 14.ISBN978-0-415-17415-2.

- ^Strong, 195

- ^abManning, Patrick (2006). "Slavery & Slave Trade in West Africa 1450-1930".Themes in West Africa's history.Akyeampong, Emmanuel Kwaku. Athens: Ohio University. pp. 102–103.ISBN978-0-8214-4566-2.OCLC745696019.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2020.Retrieved24 August2020.

- ^Strong, 194

- ^Frankopan, 200. "By the time Columbus set sail, Madeira alone was producing more than 3 million pounds in weight of sugar per year—albeit at the cost of what one scholar has described as early modern 'ecocide,' as forests were cleared and non-native animal species like rabbits and rats multiplied in such numbers that they were seen as a form of divine punishment."

- ^Strong, 194–195, 195 quoted

- ^Strong, 75

- ^Strong, 133–134, 195–197

- ^Strong, 309

- ^Abreu y Galindo, J. de (1977). A. Cioranescu (ed.).Historia de la conquista de las siete islas de Canarias.Tenerife: Goya ediciones.

- ^Antonio Benítez Rojo (1996).The Repeating: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective.James E. Maraniss (translation). Duke University Press. p. 93.ISBN0-8223-1865-2.

- ^"The Origins of Sugar from Beet".EUFIC.3 July 2001. Archived fromthe originalon 1 August 2020.Retrieved29 March2020.

- ^Marggraf (1747)"Experiences chimiques faites dans le dessein de tirer un veritable sucre de diverses plantes, qui croissent dans nos contrées"Archived31 December 2022 at theWayback Machine[Chemical experiments made with the intention of extracting real sugar from diverse plants that grow in our lands],Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Berlin,pages 79–90.

- ^Achard (1799)"Procédé d'extraction du sucre de bette"Archived22 October 2022 at theWayback Machine(Process for extracting sugar from beets),Annales de Chimie,32:163–168.

- ^Wolff, G. (1953). "Franz Karl Achard, 1753–1821; a contribution of the cultural history of sugar".Medizinische Monatsschrift.7(4): 253–4.PMID13086516.

- ^"Festveranstaltung zum 100jährigen Bestehen des Berliner Institut für Zuckerindustrie".Technical University of Berlin.23 November 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 24 August 2007.Retrieved29 March2020.

- ^Larousse Gastronomique.Éditions Larousse.13 October 2009. p. 1152.ISBN9780600620426.

- ^"Andreas Sigismund Marggraf | German chemist".Encyclopedia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 29 March 2020.Retrieved29 March2020.

- ^abMintz, Sidney (1986).Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History.Penguin.ISBN978-0-14-009233-2.

- ^Otter, Chris (2020).Diet for a large planet.USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 73.ISBN978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^"Forced Labour".The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 4 December 2016.Retrieved1 February2012.

- ^Lai, Walton (1993).Indentured labor, Caribbean sugar: Chinese and Indian migrants to the British West Indies, 1838–1918.Johns Hopkins University Press.ISBN978-0-8018-7746-9.

- ^Vertovik, Steven; (Robin Cohen, ed.) (1995).The Cambridge survey of world migration.Cambridge University Press. pp.57–68.ISBN978-0-521-44405-7.

- ^Laurence, K (1994).A Question of Labour: Indentured Immigration Into Trinidad & British Guiana, 1875–1917.St Martin's Press.ISBN978-0-312-12172-3.

- ^"St. Lucia's Indian Arrival Day".Caribbean Repeating Islands. 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2017.Retrieved1 February2012.

- ^"Indian indentured labourers".The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2011.Retrieved1 February2012.

- ^Early Sugar Industry of Bihar – BihargathaArchived10 September 2011 at theWayback Machine.Bihargatha.in. Retrieved on 7 January 2012.

- ^ Compare: Bosma, Ulbe (2013).The Sugar Plantation in India and Indonesia: Industrial Production, 1770–2010.Studies in Comparative World History. Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1-107-43530-8.Retrieved3 September2018.

- ^"How Sugar is Made – the History".SKIL: Sugar Knowledge International.Archivedfrom the original on 20 October 2002.Retrieved28 March2012.

- ^"A Visit to the Tate & Lyle Archive".The Sugar Girls blog. 10 March 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 30 July 2012.Retrieved11 March2012.

- ^"Dačice".Město Dačice.Archivedfrom the original on 2 September 2021.Retrieved2 September2021.

- ^ Barrett, Duncan & Nuala Calvi (2012).The Sugar Girls.Collins. p.ix.ISBN978-0-00-744847-0.

- ^Otter, Chris (2020).Diet for a large planet.USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 96.ISBN978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^abHicks, Jesse (Spring 2010)."The Pursuit of Sweet".Science History Institute.Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2018.Retrieved28 October2018.

- ^"1953: Sweet rationing ends in Britain".BBC.5 February 1953.Archivedfrom the original on 25 December 2007.Retrieved28 October2018.

- ^Nilsson, Jeff (5 May 2017)."Could You Stomach America's Wartime Sugar Ration? 75 Years Ago".Saturday Evening Post.Archivedfrom the original on 29 October 2018.Retrieved28 October2018.

- ^Lee, K. (1946)."Sugar Supply".CQ Press.Archivedfrom the original on 29 October 2018.Retrieved28 October2018.

- ^"Rationing of food and clothing during the Second World War".The Australian War Memorial. 25 October 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 29 October 2018.Retrieved28 October2018.

- ^Ur-Rehman, S; Mushtaq, Z; Zahoor, T; Jamil, A; Murtaza, MA (2015). "Xylitol: a review on bioproduction, application, health benefits, and related safety issues".Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.55(11): 1514–28.doi:10.1080/10408398.2012.702288.PMID24915309.S2CID20359589.

- ^abcPigman, Ward; Horton, D. (1972). Pigman and Horton (ed.).The Carbohydrates: Chemistry and Biochemistry Vol 1A(2nd ed.). San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 1–67.ISBN978-0-12-556352-9.

- ^Joshi, S; Agte, V (1995). "Digestibility of dietary fiber components in vegetarian men".Plant Foods for Human Nutrition (Dordrecht, Netherlands).48(1): 39–44.doi:10.1007/BF01089198.PMID8719737.S2CID25995873.

- ^The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals(11th ed.), Merck, 1989,ISBN091191028X,8205.

- ^Edwards, William P. (9 November 2015).The Science of Sugar Confectionery.Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 120.ISBN978-1-78262-609-1.

- ^"CSB Releases New Safety Video," Inferno: Dust Explosion at Imperial Sugar "".U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board.Washington, D.C. 7 October 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2020.Retrieved17 May2021.

- ^Woo, K. S.; Kim, H. Y.; Hwang, I. G.; Lee, S. H.; Jeong, H. S. (2015)."Characteristics of the Thermal Degradation of Glucose and Maltose Solutions".Prev Nutr Food Sci.20(2): 102–9.doi:10.3746/pnf.2015.20.2.102.PMC4500512.PMID26175997.

- ^abcdBuss, David; Robertson, Jean (1976).Manual of Nutrition; Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 5–9.

- ^Kretchmer, Norman; Claire B. Hollenbeck (1991).Sugars and Sweeteners.CRC Press, Inc.ISBN978-0-8493-8835-4.

- ^Raven, Peter H. & George B. Johnson (1995). Carol J. Mills (ed.).Understanding Biology(3rd ed.). WM C. Brown. p. 203.ISBN978-0-697-22213-8.

- ^Teller, George L. (January 1918)."Sugars Other Than Cane or Beet".The American Food Journal:23–24.Archivedfrom the original on 15 April 2023.Retrieved19 March2023.

- ^Schenck, Fred W. (2006). "Glucose and Glucose-Containing Syrups".Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry.Wiley-VCH, Weinheim.doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_457.pub2.ISBN3527306730.

- ^"Code of Federal Regulations Title 21".AccessData, US Food and Drug Administration.Archivedfrom the original on 6 September 2020.Retrieved12 September2020.

- ^Ireland, Robert (25 March 2010).A Dictionary of Dentistry.OUP Oxford.ISBN978-0-19-158502-9.

- ^"Lactase".Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^"Maltase".Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^"Sucrase".Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^Uselink to FoodData Central (USDA)Archived3 April 2019 at theWayback Machineand then search for the particular food, and click on "SR Legacy Foods".

- ^ab"Sugar: World Markets and Trade"(PDF).Foreign Agricultural Service, US Department of Agriculture. November 2017.Archived(PDF)from the original on 23 November 2018.Retrieved20 May2018.

- ^"Sugarcane production in 2020, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)".UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2017.Retrieved27 April2022.

- ^World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023.Food and Agriculture Organization.2023.doi:10.4060/cc8166en.ISBN978-92-5-138262-2.Retrieved13 December2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021.Food and Agriculture Organization. 2021.doi:10.4060/cb4477en.ISBN978-92-5-134332-6.S2CID240163091.Archivedfrom the original on 3 November 2021.Retrieved13 December2021– via www.fao.org.

- ^abcd"How Cane Sugar is Made – the Basic Story".Sugar Knowledge International.Archivedfrom the original on 22 September 2018.Retrieved24 September2018.

- ^Flynn, Kerry (23 April 2016)."India Drought 2016 May Lead 29–35% Drop In Sugar Output For 2016–17 Season: Report".International Business Times.Archivedfrom the original on 9 October 2016.Retrieved27 October2016.

- ^"Sugar beet production in 2020, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)".UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2017.Retrieved27 April2022.

- ^"Biennial beet".GMO Compass. Archived fromthe originalon 2 February 2014.Retrieved26 January2014.

- ^ab"How Beet Sugar is Made".Sugar Knowledge International.Archivedfrom the original on 21 March 2012.Retrieved22 March2012.

- ^"Tantangan Menghadapi Ketergantungan Impor Gula Rafinasi"(in Indonesian). Asosiasi Gula Rafinasi Indonesia. Archived fromthe originalon 13 April 2014.Retrieved9 April2014.

- ^"Rafinasi Vs Gula Kristal Putih"(in Indonesian). Kompas Gramedia. 29 July 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 13 April 2014.Retrieved9 April2014.

- ^"Refining and Processing Sugar"(PDF).The Sugar Association. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 February 2015.Retrieved16 April2014.

- ^Pakpahan, Agus; Supriono, Agus, eds. (2005). "Bagaimana Gula Dimurnikan – Proses Dasar".Ketika Tebu Mulai Berbunga(in Indonesian). Bogor: Sugar Observer.ISBN978-979-99311-0-8.

- ^"How Sugar is Refined".SKIL.Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2012.Retrieved22 March2012.

- ^Deulgaonkar, Atul (12–25 March 2005)."A case for reform".Frontline.22(8). Archived from the original on 28 July 2011.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^abPakpahan, Agus; Supriono, Agus, eds. (2005). "Industri Rafinasi Kunci Pembuka Restrukturisasi Industri Gula Indonesia".Ketika Tebu Mulai Berbunga(in Indonesian). Bogor: Sugar Observer. pp. 70–72.ISBN978-979-99311-0-8.

- ^abc"Sugar types".The sugar association.Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2020.Retrieved23 September2019.

- ^"Types and uses".Sugar Nutrition UK.Archivedfrom the original on 5 August 2012.Retrieved23 March2012.

- ^abcdefg"The journey of sugar".British Sugar. Archived fromthe originalon 26 March 2011.Retrieved23 March2012.

- ^Robinson, Jancis (2006).The Oxford Companion to Wine(3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp.665–66.ISBN978-0-19-860990-2.

- ^Hofman, D. L; Van Buul, V. J; Brouns, F. J (2015)."Nutrition, Health, and Regulatory Aspects of Digestible Maltodextrins".Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.56(12): 2091–2100.doi:10.1080/10408398.2014.940415.PMC4940893.PMID25674937.

- ^European Parliament and Council (1990)."Council Directive on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs".Council Directive of 24 September 1990 on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs.p. 4.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2011.Retrieved28 September2011.

- ^"Food Balance Sheets".Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 9 October 2016.Retrieved28 March2012.

- ^Otter, Chris (2020).Diet for a large planet.USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 22.ISBN978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^Amber Pariona (25 April 2017)."Top Sugar Consuming Nations In The World".World Atlas.Archivedfrom the original on 22 June 2022.Retrieved20 May2018.

- ^abUnited States Food and Drug Administration(2024)."Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels".FDA.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2024.Retrieved28 March2024.

- ^abNational Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.).Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium.The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).ISBN978-0-309-48834-1.PMID30844154.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2024.Retrieved21 June2024.

- ^"Sugars, granulated (sucrose) in 4 grams (from pick list)".Conde Nast for the USDA National Nutrient Database, version SR-21. 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 7 March 2015.Retrieved13 May2017.

- ^O'Connor, Anahad (12 June 2007)."The Claim: Brown Sugar Is Healthier Than White Sugar".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 13 May 2017.Retrieved13 May2017.

- ^Mozaffarian, Dariush (2 May 2017). "Conflict of Interest and the Role of the Food Industry in Nutrition Research".JAMA.317(17): 1755–56.doi:10.1001/jama.2017.3456.ISSN0098-7484.PMID28464165.

- ^Anderson, P.; Miller, D. (11 February 2015)."Commentary: Sweet policies"(PDF).BMJ.350(feb10 16): 780–h780.doi:10.1136/bmj.h780.ISSN1756-1833.PMID25672619.S2CID34501758.

- ^abcKearns, C. E.; Schmidt, L. A; Glantz, S. A (2016)."Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents".JAMA Internal Medicine.176(11): 1680–85.doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394.PMC5099084.PMID27617709.

- ^Kearns, Cristin E.; Glantz, Stanton A.; Schmidt, Laura A. (10 March 2015)."Sugar Industry Influence on the Scientific Agenda of the National Institute of Dental Research's 1971 National Caries Program: A Historical Analysis of Internal Documents".PLOS Medicine.12(3). Simon Capewell (ed.): 1001798.doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001798.ISSN1549-1676.PMC4355299.PMID25756179.

- ^Flint, Stuart W. (1 August 2016)."Are we selling our souls? Novel aspects of the presence in academic conferences of brands linked to ill health".J Epidemiol Community Health.70(8): 739–40.doi:10.1136/jech-2015-206586.ISSN0143-005X.PMID27009056.S2CID35094445.Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2018.Retrieved25 March2018.(secondISSN1470-2738)

- ^Aaron, Daniel G.; Siegel, Michael B. (January 2017). "Sponsorship of National Health Organizations by Two Major Soda Companies".American Journal of Preventive Medicine.52(1): 20–30.doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.010.ISSN0749-3797.PMID27745783.

- ^Schillinger, Dean; Tran, Jessica; Mangurian, Christina; Kearns, Cristin (20 December 2016)."Do Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Cause Obesity and Diabetes? Industry and the Manufacture of Scientific Controversy"(PDF).Annals of Internal Medicine.165(12): 895–97.doi:10.7326/L16-0534.ISSN0003-4819.PMC7883900.PMID27802504.S2CID207537905.Archived(PDF)from the original on 3 September 2018.Retrieved21 March2018.(original url, paywalledArchived31 December 2022 at theWayback Machine:Author's conflict of interest disclosure formsArchived3 September 2018 at theWayback Machine)

- ^Bes-Rastrollo, Maira; Schulze, Matthias B.; Ruiz-Canela, Miguel; Martinez-Gonzalez, Miguel A. (2013)."Financial conflicts of interest and reporting bias regarding the association between sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review of systematic reviews".PLOS Medicine.10(12): 1001578.doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001578.PMC3876974.PMID24391479.

- ^O’Connor, Anahad (31 October 2016)."Studies Linked to Soda Industry Mask Health Risks".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Archivedfrom the original on 21 March 2018.Retrieved23 March2018.

- ^Moodie, Rob; Stuckler, David; Monteiro, Carlos; Sheron, Nick; Neal, Bruce; Thamarangsi, Thaksaphon; Lincoln, Paul; Casswell, Sally (23 February 2013). "Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries".The Lancet.381(9867): 670–79.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62089-3.ISSN0140-6736.PMID23410611.S2CID844739.

- ^O’Connor, Anahad (9 August 2015)."Coca-Cola Funds Scientists Who Shift Blame for Obesity Away From Bad Diets".Well.Archivedfrom the original on 25 June 2022.Retrieved24 March2018.

- ^Lipton, Eric (11 February 2014)."Rival Industries Sweet-Talk the Public".The New York Times.ISSN0362-4331.Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2018.Retrieved23 March2018.

- ^Sifferlin, Alexandra (10 October 2016)."Soda Companies Fund 96 Health Groups In the U.S."Time.Retrieved24 March2018.

- ^abcJoint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003)."WHO Technical Report Series 916: Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 25 June 2016.Retrieved25 December2013.

- ^Hill, J O; Prentice, A M (1 July 1995)."Sugar and body weight regulation".The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.62(1): 264S–273S.doi:10.1093/ajcn/62.1.264S.ISSN0002-9165.PMID7598083.

- ^Malik, V. S.; Popkin, B. M.; Bray, G. A.; Despres, J.-P.; Willett, W. C.; Hu, F. B. (2010)."Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: A meta-analysis".Diabetes Care.33(11): 2477–83.doi:10.2337/dc10-1079.PMC2963518.PMID20693348.

- ^Malik, Vasanti S.; Pan, An; Willett, Walter C.; Hu, Frank B. (1 October 2013)."Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis".The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.98(4): 1084–1102.doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.058362.ISSN0002-9165.PMC3778861.PMID23966427.

- ^abc"Does sugar cause cancer?".Cancer Council Australia.2021.Archivedfrom the original on 28 March 2024.

- ^"Does Sugar Cause Cancer?".American Society of Clinical Oncology.2021. Archived fromthe originalon 1 October 2023.

- ^ab"Sugar and cancer – what you need to know".Cancer Research UK.2023.Archivedfrom the original on 6 January 2024.

- ^"The Sugar and Cancer Connection".American Institute for Cancer Research.2016.Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2024.

- ^"Curbing global sugar consumption"(PDF).World Cancer Research Fund International.2015.Archived(PDF)from the original on 29 March 2024.

- ^Clinton SK, Giovannucci EL, Hursting SD (2020)."The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Third Expert Report on Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: Impact and Future Directions".The Journal of Nutrition.150(4): 663–671.doi:10.1093/jn/nxz268.PMC7317613.PMID31758189.

- ^Del-Ponte, Bianca; Quinte, Gabriela Callo; Cruz, Suélen; Grellert, Merlen; Santos, Iná S. (2019)."Dietary patterns and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A systematic review and meta-analysis".Journal of Affective Disorders.252:160–173.doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.061.hdl:10923/18896.PMID30986731.

- ^Mantantzis, Konstantinos; Schlaghecken, Friederike; Sünram-Lea, Sandra I.; Maylor, Elizabeth A. (1 June 2019)."Sugar rush or sugar crash? A meta-analysis of carbohydrate effects on mood".Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.101:45–67.doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.016.ISSN0149-7634.PMID30951762.

- ^Wolraich, Mark L. (22 November 1995)."The Effect of Sugar on Behavior or Cognition in Children: A Meta-analysis".JAMA.274(20): 1617–1621.doi:10.1001/jama.1995.03530200053037.ISSN0098-7484.PMID7474248.

- ^Mantantzis, Konstantinos; Schlaghecken, Friederike; Sünram-Lea, Sandra I.; Maylor, Elizabeth A. (1 June 2019)."Sugar rush or sugar crash? A meta-analysis of carbohydrate effects on mood"(PDF).Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews.101:45–67.doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.016.PMID30951762.S2CID92575160.Archived(PDF)from the original on 6 May 2020.Retrieved30 April2020.

- ^Visram, Shelina; Cheetham, Mandy; Riby, Deborah M; Crossley, Stephen J; Lake, Amelia A (1 October 2016)."Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: a rapid review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes".BMJ Open.6(10): e010380.doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010380.ISSN2044-6055.PMC5073652.PMID27855083.

- ^Moynihan, P. J; Kelly, S. A (2014)."Effect on Caries of Restricting Sugars Intake: Systematic Review to Inform WHO Guidelines".Journal of Dental Research.93(1): 8–18.doi:10.1177/0022034513508954.PMC3872848.PMID24323509.

- ^Marriott BP, Olsho L, Hadden L, Connor P (2010). "Intake of added sugars and selected nutrients in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2006".Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.50(3): 228–58.doi:10.1080/10408391003626223.PMID20301013.S2CID205689533.

- ^abPanel on Macronutrients; Panel on the Definition of Dietary Fiber; Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients; Subcommittee on Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes; the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes; Food and Nutrition Board;Institute of Medicineof theNational Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine;National Research Council(2005).Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids.Washington, DC: National Academies Press.ISBN978-0-309-08525-0.Retrieved4 December2018.

Although there were insufficient data to set a UL [Tolerable Upper Intake Levels] for added sugars, a maximal intake level of 25 percent or less of energy is suggested to prevent the displacement of foods that are major sources of essential micronutrients

- ^World Health Organization (2015).Guideline. Sugars intake for adults and children(PDF)(Report). Geneva: WHO Press.ISBN978-92-4-154902-8.

- ^Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (22 February 2021)."Labeling & Nutrition – Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label".www.fda.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2014.Retrieved10 March2017.

- ^What We Eat In America, NHANES 2013–2014Archived24 February 2017 at theWayback Machine.

- ^"Measurement & conversion charts".Domino Sugar.2011.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2014.

- ^"Engineering Resources – Bulk Density Chart".Powder and Bulk.Archived fromthe originalon 27 October 2002.

Sources

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from afree contentwork. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken fromWorld Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023,FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from afree contentwork. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken fromWorld Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023,FAO, FAO.

Further reading

[edit]- Barrett, Duncan; Calvi, Nuala (2012).The Sugar Girls.Collins.ISBN978-0-00-744847-0.

- Chisholm, Hugh,ed. (1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Frankopan, Peter,The Silk Roads: A New History of the World,2016, Bloomsbury,ISBN9781408839997

- Saulo, Aurora A. (March 2005)."Sugars and Sweeteners in Foods"(PDF).College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources.

- Strong, Roy(2002),Feast: A History of Grand Eating,Jonathan Cape,ISBN0224061380