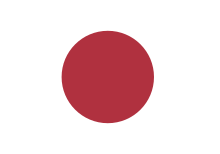

Flag of Japan

| |

| Nisshōki[1]orHinomaru[2] | |

| Use | Civilandstate flag,civilandstate ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3[1] |

| Adopted | |

| Design | A crimson disc centered on a white field |

Thenational flagofJapanis a rectangular white banner with a crimson-red circle at its center. The flag is officially called theNisshōki(Nhật chương kỳ,'flag of the sun')but is more commonly known in Japan as theHinomaru(Nhật の hoàn,'Ball of the sun').It embodies the country'ssobriquet:theLand of the Rising Sun.

TheNisshōkiflag is designated as the national flag in theAct on National Flag and Anthem,which was promulgated and became effective on 13 August 1999. Although no earlier legislation had specified a national flag, the sun-disc flag had already become thede factonational flag of Japan. Two proclamations issued in 1870 by theDaijō-kan,the governmental body of the earlyMeiji period,each had a provision for a design of the national flag. A sun-disc flag was adopted as the national flag for merchant ships under Proclamation No. 57 of Meiji 3 (issued on 27 January 1870),[3]and as the nationalflag used by the Navyunder Proclamation No. 651 of Meiji 3 (issued on 3 October 1870).[4]Use of theHinomaruwas severely restricted during the early years of theAllied occupation of JapanafterWorld War II;these restrictions were later relaxed.

The sun plays an important role inJapanese mythologyand religion, as theEmperoris said to be thedirect descendantof theShintosun goddessAmaterasu,and the legitimacy of theruling houserested on this divine appointment. Thename of the countryas well as the design of the flag reflect this central importance of the sun. The ancient historyShoku Nihongisays thatEmperor Monmuused a flag representing the sun in his court in 701, the first recorded use of a sun-motif flag in Japan.[5][6]The oldest existing flag is preserved in Unpō-ji temple,Kōshū, Yamanashi,which is older than the 16th century, and an ancient legend says that the flag was given to the temple byEmperor Go-Reizeiin the 11th century.[7][8][9]During theMeiji Restoration,the sun disc and theRising Sun Ensignof theImperial Japanese NavyandArmybecame major symbols in the emergingJapanese Empire.Propaganda posters, textbooks, and films depicted the flag as a source of pride and patriotism. In Japanese homes, citizens were required to display the flag during national holidays, celebrations and other occasions as decreed by the government. Different tokens of devotion to Japan and its Emperor featuring theHinomarumotif became popular among the public during theSecond Sino-Japanese Warand other conflicts. These tokens ranged from slogans written on the flag to clothing items and dishes that resembled the flag.

Public perception of the national flag varies. Historically, both Western and Japanese sources have described the flag as a powerful and enduring symbol to the Japanese. Since the end of World War II (thePacific War), the use of the flag and the national anthemKimigayohas been a contentious issue for Japan's public schools, and disputes about their use have led to protests and lawsuits. Severalmilitary banners of Japanare based on theHinomaru,including the sunrayed naval ensign. TheHinomarualso serves as a template for other Japanese flags in public and private use.

History

[edit]Ancient to medieval

[edit]

Flag of Japan (1868–1999)

Flag of Japan (1868–1999)The exact origin of theHinomaruis unknown,[10]but the rising sun has carried symbolic meaning since the early 7th century. Japan is often referred to as "the land of the rising sun".[11]The Japanese archipelago is east of the Asian mainland, and is thus where the sun "rises". In 607, an official correspondence that began with "from the Emperor of the rising sun" was sent to the ChineseEmperor Yang of Sui.[12]

The sun is closely related to theImperial family,as legend states the imperial throne was descended from the sun goddessAmaterasu.[13][14]The religion, which is categorized as the ancientKo-Shintōreligion of theJapanese people,includesnature worshipandanimism,and thefaithhas been worshiping thesun,especially inagricultureandfishing.The Imperial God,Amaterasu-ōmikami,is the sun goddess. From theYayoi period(300 BCE) to theKofun period(250 CE) (Yamato period), theNaikō Kamonkyō,a large bronze mirror with patterns like a flower-petal, was used as a celebration of the shape of the shining sun and there is a theory that one of theThree Sacred Treasures,Yata no Kagami,is used like this mirror.[15]

During theEastern expedition,Emperor Jimmu's brother Itsuse no Mikoto was killed in a battle against the local chieftain Nagasunehiko ( "the long-legged man" ) in Naniwa (modern-day Osaka).Emperor Jimmurealized, as a descendant of the sun, that he did not want to fight towards the sun (to the east), but to fight from the sun (to the west). The Emperor's clan therefore went to the east side ofKii Peninsulato battle westward. They reachedKumano(orIse) and went towards Yamato. They were victorious at the second battle with Nagasunehiko and conquered theKinki region.[16][17]

The use of the sun-shaped flag was thought to have taken place since the emperor's direct imperial rule (Thân chính) was established after theIsshi Incidentin 645 (first year of theTaika).[18]

The Japanese history textShoku Nihongi,completed in 797, has the first recorded use of the sun-motif flag byEmperor Monmu'sChōga(Triều hạ,'new year's greetings ceremony')in 701 (the first year of theTaihō era).[5][6]For the decoration of the ceremony hall on New Year's Day theNissho(Nhật tượng,'the flag with the golden sun')was raised.[5][6]

One prominent theory is influenced by the results of theGenpei War(1180–1185).[19]Until theHeian period,the Nishiki flag(Cẩm の ngự kỳ,Nishiki no mihata),a symbol of the Imperial Court, had a golden sun circle and a silver moon circle on a red background.[19]At the end of the Heian era, theTaira clancalled themselves a government army and used the red flag with a gold circle(Xích địa kim hoàn)as per the Imperial Court.[19]The Genji (Minamoto clan) were in opposition so they used a white flag with a red circle(Bạch địa xích hoàn)when they fought the Genpei War (1180–1185).[19]When the Taira clan was defeated, the samurai government(Mạc phủ,bakufu)was formed by the Genji.[19]The warlords who came after such asOda NobunagaandTokugawa Ieyasurealized they were successors of Genji, and so raised theHinomaruflag in battle.[19]

In the 12th-century workThe Tale of the Heike,it was written that differentsamuraicarried drawings of the sun on their fans.[20]One legend related to the national flag is attributed to theBuddhistpriestNichiren.Supposedly, during a 13th-centuryMongolianinvasion of Japan, Nichiren gave a sun banner to theshōgunto carry into battle.[21]

During theBattle of Nagashino(28 June 1575), Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu's allied forces foughtTakeda Katsuyori.[19]Both Nobunaga and Ieyasu had their own flags with family crests, but they also held theHinomaru.[19]On the other hand, the Takeda clan side also raised theHinomaru.[19]Therefore, theHinomaruwas used as a national symbol.[19]

One of Japan's oldest flags is housed at the Unpo-ji temple inKōshūcity,Yamanashi Prefecture.[19]Legend states it was given byEmperor Go-ReizeitoMinamoto no Yoshimitsuand has been treated as a family treasure by theTakeda clanfor the past 1,000 years,[19][22]and is at least older than 16th century.

In the 16th centuryunification period,eachdaimyōhad flags that were used primarily in battle. Most of the flags were long banners usually charged with themon(family crest) of thedaimyōlord. Members of the same family would have had different flags to carry into battle. The flags served as identification and were displayed by soldiers on their backs and horses. Generals also had their own flags, most of which differed from soldiers' flags due to their square shape.[23][page needed]

In 1854, during theTokugawa shogunate,Japanese ships were ordered to hoist theHinomaruto distinguish themselves from foreign ships.[20]Before then, different types ofHinomaruflags were used on vessels that were trading with the U.S. and Russia.[10]TheHinomaruwas decreed the merchant flag of Japan in 1870 and was the legal national flag from 1870 to 1885, making it the first national flag Japan adopted.[24][25]

While the idea of national symbols was strange to the Japanese, the Meiji Government needed them to communicate with the outside world. This became especially important after the landing of U.S. CommodoreMatthew Perryin Yokohama Bay.[26]Further Meiji Government implementations gave more identifications to Japan, including the anthemKimigayoand the imperial seal.[27]In 1885, all previous laws not published in the Official Gazette of Japan were abolished.[28]Because of this ruling by the new cabinet of Japan, theHinomaruwas thede factonational flag since no law was in place after theMeiji Restoration.[29]

Early conflicts and the Pacific War

[edit]

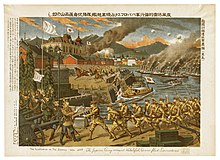

The use of the national flag grew as Japan sought to develop an empire, and theHinomaruwas present at celebrations after victories in theFirst Sino-JapaneseandRusso-Japanese Wars.The flag was also used in war efforts throughout the country.[30]A Japanese propaganda film in 1934 portrayed foreign national flags as incomplete or defective with their designs, whilst portraying the Japanese flag as perfect in all forms.[31]In 1937, a group of girls fromHiroshima Prefectureshowed solidarity with Japanese soldiers fighting in China during theSecond Sino-Japanese War,by eating "flag meals" that consisted of anumeboshiin the middle of a bed of rice. TheHinomarubentobecame the main symbol of Japan's war mobilization and solidarity with its soldiers until the 1940s.[32]

Japan's early victories in the Sino-Japanese War resulted in theHinomaruagain being used for celebrations. It was seen in the hands of every Japanese during parades.[30]

Textbooks during this period also had theHinomaruprinted with various slogans expressing devotion to the Emperor and the country. Patriotism was taught as a virtue to Japanese children. Expressions of patriotism, such as displaying the flag or worshiping the Emperor daily, were all part of being a "good Japanese".[33]

The flag was a tool of Japanese imperialism in the occupied Southeast Asian areas during theSecond World War:people had to use the flag,[34]and schoolchildren sangKimigayoin morning flag raising ceremonies.[35]Local flags were allowed for some areas such as thePhilippines,Indonesia,andManchukuo.[36][37][38]InKoreawhich was part of the Empire of Japan, theHinomaruand other symbols were used to declare that the Koreans were subjects of the empire.[39]

During the Pacific War, Americans coined the derogatory term "meatballs" for theHinomaruand Japanesemilitary aircraft insignia.[40]To the Japanese, theHinomaruwas the "Rising Sun flag that would light the darkness of the entire world".[41]To Westerners, it was one of the Japanese military's most powerful symbols.[42]

U.S. occupation

[edit]Right:The civil and naval ensign ofoccupied Japan.TheHinomarusimultaneously remained inde factouse.

TheHinomaruwas thede factoflag of Japan throughoutWorld War IIand the occupation period.[29]During theoccupation of Japanafter World War II, permission from theSupreme Commander of the Allied Powers(SCAPJ) was needed to fly theHinomaru.[43][44]Sources differ on the degree to which the use of theHinomaruflag was restricted; some use the term "banned;"[45][46]however, while the original restrictions were severe, they did not amount to an outright ban.[29]

After World War II, anensignwas used by Japanese civil ships of the United States Naval Shipping Control Authority for Japanese Merchant Marines.[47]Modified from the "E"signal code,the ensign was used from September 1945 until the U.S. occupation of Japan ceased.[48]U.S. ships operating in Japanese waters used a modified "O" signal flag as their ensign.[49]

On 2 May 1947, GeneralDouglas MacArthurlifted the restrictions on displaying theHinomaruin the grounds of theNational Diet Building,on theImperial Palace,on thePrime Minister's residence,and on the Supreme Court building with the ratification of the newConstitution of Japan.[50][51]Those restrictions were further relaxed in 1948, when people were allowed to fly the flag on national holidays. In January 1949, the restrictions were abolished and anyone could fly theHinomaruat any time without permission. As a result, schools and homes were encouraged to fly theHinomaruuntil the early 1950s.[43]

Postwar to 1999

[edit]

Since World War II, Japan's flag has been criticized for its association with the country'smilitaristicpast. Similar objections have also been raised to the current national anthem of Japan,Kimigayo.[22]The feelings about theHinomaruandKimigayorepresented a general shift from a patriotic feeling aboutDai Nippon(Great Japan) to the pacifist and anti-militaristNihon.Because of this ideological shift, the flag was used less often in Japan directly after the war even though restrictions were lifted by the SCAPJ in 1949.[44][52]

As Japan began to re-establish itself diplomatically, theHinomaruwas used as a political weapon overseas. In a visit byEmperor HirohitoandEmpress Kōjunto theNetherlands,theHinomaruwas burned by Dutch citizens who demanded that he either be sent home to Japan or tried for the deaths of Dutchprisoners of warduring the Second World War.[53]Domestically, the flag was not even used in protests against a newStatus of Forces Agreementbeing negotiated between the U.S. and Japan. The most common flag used by the trade unions and other protesters was thered flagof revolt.[54]

An issue with theHinomaruand national anthem was raised once again when Tokyo hosted the1964 Summer Olympic Games.Before the Olympic Games, the size of the sun disc of the national flag was changed partly because the sun disc was not considered striking when it was being flown with other national flags.[44]Tadamasa Fukiura, a color specialist, chose to set the sun disc at two-thirds of the flag's length. Fukiura also chose the flag colors for the 1964 games as well as for the1998 Winter Olympicsin Nagano.[55]

In 1989, the death of Emperor Hirohito once again raised moral issues about the national flag. Conservatives felt that if the flag could be used during the ceremonies without reopening old wounds, they might have a chance to propose that theHinomarubecome the national flag without being challenged about its meaning.[56]During an official six-day mourning period, flags were flown at half staff or draped in black bunting all across Japan.[57]Despite reports of protesters vandalizing theHinomaruon the day of the Emperor's funeral,[58]schools' right to fly the Japanese flag athalf-staffwithout reservations brought success to the conservatives.[56]

Since 1999

[edit]

TheLaw Regarding the National Flag and National Anthemwas passed in 1999, choosing both theHinomaruandKimigayoas Japan's national symbols. The passage of the law stemmed from the suicide of the principal ofSera High SchoolinSera,Hiroshima,Toshihiro Ishikawa, who could not resolve a dispute between his school board and his teachers over the use of theHinomaruandKimigayo.[59][60]The Act is one of the most controversial laws passed by theDietsince the 1992 "Law Concerning Cooperation for United Nations Peacekeeping Operations and Other Operations", also known as the "International Peace Cooperation Law".[61]

Prime MinisterKeizō Obuchiof theLiberal Democratic Party(LDP) decided to draft legislation to make theHinomaruandKimigayoofficial symbols of Japan in 2000. HisChief Cabinet Secretary,Hiromu Nonaka,wanted the legislation to be completed by the 10th anniversary of EmperorAkihito'senthronement.[62]This is not the first time legislation was considered for establishing both symbols as official. In 1974, with the backdrop of the 1972 return of Okinawa to Japan and the1973 oil crisis,Prime MinisterKakuei Tanakahinted at a law being passed enshrining both symbols in the law of Japan.[63]In addition to instructing the schools to teach and playKimigayo,Tanaka wanted students to raise theHinomaruflag in a ceremony every morning, and to adopt a moral curriculum based on certain elements of theImperial Rescript on Educationpronounced by theMeiji Emperorin 1890.[64]Tanaka was unsuccessful in passing the law through the Diet that year.[65]

The main supporters of the bill were the LDP and theKomeito(CGP), while the opposition included theSocial Democratic Party(SDPJ) andCommunist Party(JCP), who cited the connotations both symbols had with the war era. The CPJ was further opposed for not allowing the issue to be decided by the public. Meanwhile, theDemocratic Party of Japan(DPJ) could not develop party consensus on it. DPJ President and future prime ministerNaoto Kanstated that the DPJ must support the bill because the party already recognized both symbols as the symbols of Japan.[66]Deputy Secretary General and future prime ministerYukio Hatoyamathought that this bill would cause further divisions among society and the public schools. Hatoyama voted for the bill while Kan voted against it.[62]

Before the vote, there were calls for the bills to be separated at the Diet.Waseda Universityprofessor Norihiro Kato stated thatKimigayois a separate issue more complex than theHinomaruflag.[67]Attempts to designate only theHinomaruas the national flag by the DPJ and other parties during the vote of the bill were rejected by the Diet.[68]The House of Representatives passed the bill on 22 July 1999, by a 403 to 86 vote.[69]The legislation was sent to the House of Councilors on 28 July and was passed on 9 August. It was enacted into law on 13 August.[70]

On 8 August 2009, a photograph was taken at a DPJ rally for theHouse of Representatives electionshowing a banner that was hanging from a ceiling. The banner was made of twoHinomaruflags cut and sewn together to form the shape of the DPJ logo. This infuriated the LDP and Prime MinisterTarō Asō,saying this act was unforgivable. In response, DPJ President Yukio Hatoyama (who voted for the Law Regarding the National Flag and National Anthem)[62]said that the banner was not theHinomaruand should not be regarded as such.[71]

Flag design

[edit]

Passed in 1870, the Prime Minister's Proclamation No. 57 had two provisions related to the national flag. The first provision specified who flew the flag and how it was flown; the second specified how the flag was made.[10]The ratio was seven units width and ten units length (7:10). The red disc, which represents the sun, was calculated to be three-fifths of thehoist width.The law decreed the disc to be in the center, but it was usually placed one-hundredth (1⁄100) towards the hoist.[72][73](This makes the disc appear centered when the flag is flying; this technique is used in other flags, such as those ofBangladeshandPalau.) On 3 October of the same year, regulations about the design of the merchant ensign and other naval flags were passed.[74]For the merchant flag, the ratio was two units width and three units length (2:3). The size of the disc remained the same, but the sun disc was placed one-twentieth (1⁄20) towards the hoist.[75]

When theLaw Regarding the National Flag and National Anthempassed, the dimensions of the flag were slightly altered.[1]The overall ratio of the flag was changed to two units width by three units length (2:3). The red disc was shifted towards the center, but the overall size of the disc stayed the same.[2]The background of the flag is white and the center is a red circle(Hồng sắc,beni iro),but the exact color shades were not defined in the 1999 law.[1]The only hint given about the red colour is that it is a "deep" shade.[76]

Issued by the Japan Defense Agency (now theMinistry of Defense) in 1973 (Shōwa48), specifications list the red color of the flag as 5R 4/12 and the white as N9 in theMunsell colorchart.[77]The document was changed on 21 March 2008 (Heisei20) to match the flag's construction with current legislation and updated the Munsell colours. The document listsacrylic fiberandnylonas fibers that could be used in construction of flags used by the military. For acrylic, the red color is 5.7R 3.7/15.5 and white is N9.4; nylon has 6.2R 4/15.2 for red and N9.2 for white.[77]In a document issued by theOfficial Development Assistance(ODA), the red color for theHinomaruand the ODA logo is listed asDIC156 andCMYK0-100-90-0.[78]During deliberations about theLaw Regarding the National Flag and National Anthem,there was a suggestion to either use a bright red(Xích sắc,aka iro)shade or use one from the color pool of theJapanese Industrial Standards.[79]

Colour chart

[edit]| Official colour (white) | Official colour (red) | Colour system | Source | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N9[80] | 5R 4/12[80] | Munsell | DSP Z 8701C[77] | 1973 |

| N/A | 156[81] | DIC | ODA Symbol Mark Guidelines[78] | 1995 |

Use and customs

[edit]

When theHinomaruwas first introduced, the government required citizens to greet the Emperor with the flag. There was some resentment among the Japanese over the flag,[why?]resulting in some protests. It took some time for the flag to gain acceptance among the people.[27]

Before World War II, all homes were required to displayHinomaruon national holidays.[29]Since the war, the display of the flag of Japan is mostly limited to buildings attached to national and local governments such as city halls; it is rarely seen at private homes or commercial buildings,[29]but some people and companies have advocated displaying the flag on holidays. Although the government of Japan encourages citizens and residents to fly theHinomaruduring national holidays, they are not legally required to do so.[82][83]Sincethe Emperor's 80th birthdayon 23 December 2002, theKyushu Railway Companyhas displayed theHinomaruat 330 stations.[84]

Starting in 1995, the ODA has used theHinomarumotif in their official logo. The design itself was not created by the government (the logo was chosen from 5,000 designs submitted by the public) but the government was trying to increase the visualization of theHinomaruthrough their aid packages and development programs. According to the ODA, the use of the flag is the most effective way to symbolise aid provided by the Japanese people.[85]

Hinomaru Yosegaki

[edit]

During World War II, it was a popular custom for friends, classmates, and relatives of a deploying soldier to sign aHinomaruand present it to him. The flag was also used as a good luck charm and a prayer to wish the soldier back safely from battle. One term for this kind of charm isHinomaru Yosegaki(Nhật の hoàn ký せ thư き).[86]One tradition is that no writing should touch the sun disc.[87]After battles, these flags were often captured or later found on deceased Japanese soldiers. Some of these flags have become souvenirs,[87]and some have been returned to Japan and the descendants of the deceased.[88]

In modern times, theHinomaru Yosegakiis still being used. The tradition of signing theHinomaruas a good luck charm still continues, though in a limited fashion. TheHinomaru Yosegakiis shown at sporting events to give support to the Japanese national team.[89]TheYosegaki(Ký せ thư き,group effort flag)is used for campaigning soldiers,[90]athletes, retirees, transfer students in a community and for friends. The colored paper and flag has writing with a message. In modern Japan, it is given as a present to a person at a send-off party, for athletes, a farewell party for colleagues or transfer students, for graduation and retirement. After natural disasters such as the2011 Tōhoku Earthquake and tsunamipeople write notes on aHinomaru Yosegakito show support.

Hachimaki

[edit]

Thehachimaki(Bát quyển,'helmet-scarf')is a whiteheadband(bandana) with the red sun in the middle. Phrases are usually written on it. It is worn as a symbol ofperseverance,effort, and/orcourageby the wearer. These are worn on many occasions by for example sports spectators, women giving birth, students incram school,office workers,[91]tradesmen taking pride in their work etc. During World War II, the phrases "Certain Victory"(Tất thắng,Hisshō)or "Seven Lives" was written on thehachimakiand worn bykamikazepilots. This denoted that the pilot was willing to die for his country.[92]

Hinomaru bentō

[edit]

Bentōandmakunouchiare types of Japanese lunch boxes, which can featureHinomarurice(Nhật の hoàn ご phạn,Hinomaru gohan).TheHinomaru bentōconsists ofgohan(steamed white rice) with a redumeboshi(driedplum) in the center which represents the sun and the flag of Japan. AHinomarulunch box(Nhật の hoàn biện đương,Hinomaru bentō)only has white rice and a redumeboshiin the center. The salty, vinegar-soakedumeboshiacts as a preservative for the rice. There are alsoHinomarurice bowls, which are less common.[93]

Culture and perception

[edit]

According to polls conducted by mainstream media, most Japanese people had perceived the flag of Japan as the national flag even before the passage of theLaw Regarding the National Flag and National Anthemin 1999.[94]Despite this, controversies surrounding the use of the flag in school events or media still remain. For example, liberal newspapers such as theAsahi ShimbunandMainichi Shimbunoften feature articles critical of the flag of Japan, reflecting their readerships' political spectrum.[95]To other Japanese, the flag represents the time where democracy was suppressed whenJapan was an empire.[96]

The display of the national flag at homes and businesses is also debated in Japanese society. Because of its association withuyoku dantai(right wing) activists,reactionary politics,orhooliganism,most homes and businesses do not fly the flag.[29]There is no requirement to fly the flag on any national holiday or special events. The town ofKanazawa, Ishikawaproposed plans in September 2012 to use government funds to buy flags with the purpose of encouraging citizens to fly the flag on national holidays.[97]

Negative perceptions of the national flag exist in former colonies of Japan as well as within Japan itself, such as inOkinawa Prefecture.In one notable example of this, on 26 October 1987, an Okinawan supermarket ownerburnedthe flag before the start of theNational Sports Festival of Japan.[98]The flag burner, Shōichi Chibana, burned theHinomarunot only to show opposition to atrocities committed by the Japanese army and the continued presence of U.S. forces but also to prevent it from being displayed in public.[99]Other incidents in Okinawa included the flag being torn down during school ceremonies and students refusing to honor the flag as it was being raised to the sounds ofKimigayo.[30]In the capital city ofNaha, Okinawa,theHinomaruwas raised for the first time since the return of Okinawa to Japan to celebrate the city's 80th anniversary in 2001.[100]In thePeople's Republic of ChinaandRepublic of Korea,both of which had been occupied by the Empire of Japan, the 1999 formal adoption of theHinomaruwas met with reactions of Japan moving towards the right and also a step towards re-militarization. The passage of the 1999 law also coincided with the debates about the status of theYasukuni Shrine,U.S.-Japan military cooperation, and the creation of a missile defense program. In other nations that Japan occupied, the 1999 law was met with mixed reactions or glossed over. In Singapore, the older generation still harbors ill feelings toward the flag while the younger generation does not hold similar views. The Philippine government not only believed that Japan was not going to revert to militarism, but the goal of the 1999 law was to formally establish two symbols (the flag and anthem) in law and every state has a right to create national symbols.[101]Japan has no law criminalizing the burning of theHinomaru,whereas foreign flags cannot be burned in Japan.[102][103]

Protocol

[edit]

According to protocol, the flag may fly from sunrise until sunset; businesses and schools are permitted to fly the flag from opening to closing. When flying the flags of Japan and another country at the same time in Japan, the Japanese flag takes the position of honor and the flag of the guest country flies to its right. Both flags must be at the same height and of equal size. When more than one foreign flag is displayed, Japan's flag is arranged in the alphabetical order prescribed by theUnited Nations.[104]When the flag becomes unsuitable to use, it is customarily burned in private. TheLaw Regarding the National Flag and Anthemdoes not specify on how the flag should be used, but different prefectures came up with their own regulations to use theHinomaruand other prefectural flags.[105][106]

Mourning

[edit]TheHinomaruflag has at least two mourning styles. One is to display the flag athalf-staff(Bán kỳ,han-ki),as is common in many countries. The offices of theMinistry of Foreign Affairsalso hoist the flag at half-staff when a funeral is performed for a foreign nation's head of state.[107]

An alternative mourning style is to wrap the sphericalfinialwith black cloth and place a black ribbon, known as a mourning flag(Điếu kỳ[ja],chō-ki),above the flag. This style dates back to the death ofEmperor Meijion 30 July 1912, and the Cabinet issued an ordinance stipulating that the national flag should be raised in mourning when the Emperor dies.[108]The Cabinet has the authority to announce the half-staffing of the national flag.[109]

Public schools

[edit]

Since the end of World War II, theMinistry of Educationhas issued statements and regulations to promote the usage of both theHinomaruandKimigayo(national anthem) at schools under their jurisdiction. The first of these statements was released in 1950, stating that it was desirable, but not required, to use both symbols. This desire was later expanded to include both symbols on national holidays and during ceremonial events to encourage students on what national holidays are and to promote defense education.[44]In a 1989 reform of the education guidelines, the LDP-controlled government first demanded that the flag must be used in school ceremonies and that proper respect must be given to it and toKimigayo.[110]Punishments for school officials who did not follow this order were also enacted with the 1989 reforms.[44]

The 1999curriculum guidelineissued by the Ministry of Education after the passage of theLaw Regarding the National Flag and Anthemdecrees that "on entrance and graduation ceremonies, schools must raise the flag of Japan and instruct students to sing theKimigayo,given the significance of the flag and the song. "[111]Additionally, the ministry's commentary on the 1999 curriculum guideline for elementary schools note that "given the advance of internationalization, along with fostering patriotism and awareness of being Japanese, it is important to nurture school children's respectful attitude toward the flag of Japan andKimigayoas they grow up to be respected Japanese citizens in an internationalized society. "[112]The ministry also stated that if Japanese students cannot respect their own symbols, then they will not be able to respect the symbols of other nations.[113]

Schoolshave been the center of controversy over both the anthem and the national flag.[45]The Tokyo Board of Education requires the use of both the anthem and flag at events under their jurisdiction. The order requires school teachers to respect both symbols or risk losing their jobs.[114]Some have protested that such rules violate theConstitution of Japan,but the Board has argued that since schools are government agencies, their employees have an obligation to teach their students how to be good Japanese citizens.[22]As a sign of protest, schools refused to display theHinomaruat school graduations and some parents ripped down the flag.[45]Teachers have unsuccessfully brought criminal complaints against Tokyo GovernorShintarō Ishiharaand senior officials for ordering teachers to honor theHinomaruandKimigayo.[115]After earlier opposition, theJapan Teachers Unionaccepts the use of both the flag and anthem; the smaller All Japan Teachers and Staffs Union still opposes both symbols and their use inside the school system.[116]

Related flags

[edit]Military flags

[edit]

TheJapan Self-Defense Forces(JSDF) and theJapan Ground Self-Defense Forceuse the Rising Sun Flag with eight red rays extending outward, calledHachijō-Kyokujitsuki(Bát điều húc nhật kỳ).A gold border is situated partially around the edge.[117]

A well-known variant of the sun disc design is the sun disc with 16 red rays in aSiemens starformation, which was also historically used by Japan's military, particularly theImperial Japanese Armyand theImperial Japanese Navy.The ensign, known in Japanese as theJyūrokujō-Kyokujitsuki(Thập lục điều húc nhật kỳ),was first adopted as thewar flagon 15 May 1870, and was used until the end of World War II in 1945. It was re-adopted on 30 June 1954, and is now used as the war flag and naval ensign of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) and theJapan Maritime Self-Defense Force(JMSDF).[117]JSDFChief of StaffKatsutoshi Kawanosaid the Rising Sun Flag is the Maritime Self-Defense Force sailors' "pride".[118]Due to its continued use by the Imperial Japanese Army, this flag carries the negative connotation similar to the Nazi flag in China and Korea.[119]These formerly colonised countries state that this flag is a symbol of Japanese imperialism during World War II, and was an ongoing conflict event for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. The JMSDF also employs the use of amasthead pennant.First adopted in 1914 and readopted in 1965, the masthead pennant contains a simplified version of the naval ensign at the hoist end, with the rest of the pennant colored white. The ratio of the pennant is between 1:40 and 1:90.[120]

TheJapan Air Self-Defense Force(JASDF), established independently in 1952, has only the plain sun disc as its emblem.[121]This is the only branch of service with an emblem that does not invoke the rayed Imperial Standard. However, the branch does have anensignto fly on bases and during parades. The Japan Air Self-Defense Force flag was first adopted in 1955 after the JASDF was created in 1954. The flag is cobalt blue with a gold winged eagle on top of a combined star, the moon, theHinomarusun disc and clouds.[122][123]The latest version of the JASDF flag was re-adopted on 19 March 2001.[124]

Although not an official national flag, theZ signal flagplayed a major role in Japanese naval history. On 27 May 1905, AdmiralHeihachirō Tōgōof theMikasawas preparing to engage theRussian Baltic Fleet.Before theBattle of Tsushimabegan, Togo raised the Z flag on theMikasaand engaged the Russian fleet, winning the battle for Japan. The raising of the flag said to the crew the following: "The fate of Imperial Japan hangs on this one battle; all hands will exert themselves and do their best." The Z flag was also raised on the aircraft carrierAkagion the eve of Japan's attack onPearl Harbor,Hawaii,in December 1941.[125]

-

Post WWII flag of theJapan Air Self-Defense Force(JASDF)

Post WWII flag of theJapan Air Self-Defense Force(JASDF) -

Pre-WWIIroundel(military aircraft insignia) of Navy and Army military aircraft

-

Post WWII roundel of the JASDF

Imperial flags

[edit]

The standard of the Japanese Emperor

The standard of the Japanese EmperorBeginning in 1870, flags were created for the Japanese Emperor (thenEmperor Meiji), the Empress, and other members of the imperial family.[126]At first, the Emperor's flag was ornate, with a sun resting in the center of an artistic pattern. He had flags that were used on land, at sea, and when he was in a carriage. The imperial family was also granted flags to be used at sea and while on land (one for use on foot and one carriage flag). The carriage flags were a monocoloredchrysanthemum,with 16 petals, placed in the center of a monocolored background.[74]These flags were discarded in 1889 when the Emperor decided to use the chrysanthemum on a red background as his flag. With minor changes in the color shades and proportions, the flags adopted in 1889 are still in use by the imperial family.[127][128]

The current Emperor's flag is a 16-petal chrysanthemum(Cúc hoa văn,Kikkamon),colored in gold, centered on a red background with a 2:3 ratio. The Empress uses the same flag, except the shape is that of a swallow tail. The crown prince and the crown princess use the same flags, except with a smaller chrysanthemum and a white border in the middle of the flags.[129]The chrysanthemum has been associated with the Imperial throne since the rule ofEmperor Go-Tobain the 12th century, but it did not become the exclusivesymbol of the Imperial throneuntil 1868.[126]

Subnational flags

[edit]

Each of the47 prefecturesof Japan has itsown flagwhich, like the national flag, consists of a symbol – called amon– charged upon a monocolored field (except forEhime Prefecture,where the background is bicolored).[130]There are several prefecture flags, such asHiroshima's, that match their specifications to the national flag (2:3 ratio,monplaced in the center and is3⁄5the length of the flag).[131]Some of themondisplay the name of the prefecture inJapanese characters;others are stylized depictions of the location or another special feature of the prefecture. An example of a prefectural flag is that ofNagano,where the orangekatakanacharacterna(ナ)appears in the center of a white disc. One interpretation of themonis that thenasymbol represents a mountain and the white disc, a lake. The orange color represents the sun while the white color represents the snow of the region.[132]

Municipalitiescan also adopt flags of their own. The designs of the city flags are similar to the prefectural flags: amonon a monocolored background. An example is the flag ofAmakusainKumamoto Prefecture:the city symbol is composed of thekatakanacharactera(ア)✓and surrounded by waves.[133]This symbol is centered on a white flag, with a ratio of 2:3.[134]Both the city emblem and the flag were adopted in 2006.[134]

Derivatives

[edit]

Former Japan Post flag (1872–1887)

Former Japan Post flag (1872–1887)

In addition to the flags used by the military, several other flag designs were inspired by the national flag. The formerJapan Postflag consisted of theHinomaruwith a red horizontal bar placed in the center of the flag. There was also a thin white ring around the red sun. It was later replaced by a flag that consisted of the〒 postal markin red on a white background.[135]

Two recently-designed national flags resemble the Japanese flag. In 1971,Bangladeshgained independence fromPakistan,andit adopted a national flagthat had a green background, charged with an off-centered red disc that contained a golden map of Bangladesh. The current flag, adopted in 1972, dropped the golden map and kept everything else. The Government of Bangladesh officially calls the red disc a circle;[136]the red color symbolizes the blood that was shed to create their country.[137]The island nation ofPalauuses a flag of similar design, but the color scheme is completely different. While the Government of Palau does not cite the Japanese flag as an influence on their national flag, Japan did administer Palau from 1914 until 1944.[138]Theflag of Palauis an off-centered golden-yellowfull moonon a sky blue background.[139]The moon stands for peace and a young nation while the blue background represents Palau's transition to self-government from 1981 to 1994, when it achieved full independence.[140]

The Japanese naval ensign also influenced other flag designs. One such flag design is used by theAsahi Shimbun.At the bottom hoist of the flag, one quarter of the sun is displayed. ThekanjicharacterTriềuis displayed on the flag, colored white, covering most of the sun. The rays extend from the sun, occurring in a red and white alternating order, culminating in 13 total stripes.[141][142]The flag is commonly seen at theNational High School Baseball Championship,as theAsahi Shimbunis a main sponsor of the tournament.[143]The rank flags and ensigns of the Imperial Japanese Navy also based their designs on the naval ensign.[144]

Gallery

[edit]-

Japanese flag at the Meiji Memorial

-

Japan Self-Defense Forceshonor guards holding the national flag duringMike Pence's visit.

-

Flags of Japan and other G7 states flying inToronto

-

A series of Japanese flags in a school entrance

-

Yokohama City (left) and theHinomaru(center) flying on Yokohama Harbor

-

Firefighters in Tokyo holding the Japanese national flag during a ceremony

-

Large flags of Japan at theTokyo Olympic Stadiumduring the final match of the East Asian Football Championship (14 February 2010)

-

Totenko-Rooster Crows withHinomaruand lady, 1909

See also

[edit]- List of Japanese flags

- National symbols of Japan

- Nobori– Tall Japanese banner

- Sashimono– Small banners worn by soldiers in feudal Japan

- Uma-jirushi– Massive flags used on battlefields in feudal Japan

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^abcdQuốc kỳ cập び quốc ca に quan する pháp luật

- ^abConsulate-General of Japan in San Francisco.Basic / General Information on Japan;1 January 2008 [archived11 December 2012].

- ^(in Japanese). Government of Japan – viaWikisource.

- ^Pháp lệnh toàn thư(in Japanese).National Diet.27 October 1870.doi:10.11501/787950.Archivedfrom the original on 28 March 2019.Retrieved26 February2019.

- ^abc"「 quốc kỳ 」の chân thật をどれだけ tri っていますか".23 December 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 4 February 2016.

- ^abc"Shoku Nihongi".University of California, Berkeley(see original Japanese text).Archived fromthe originalon 4 February 2021.

- ^Yamanashi Tourism Organization.Nhật の hoàn の ngự kỳ[archived1 October 2011].(in Japanese)

- ^Unpoji.Bảo vật điện の án nội[archived4 November 2011].(in Japanese)

- ^Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact: The Turning Points in Our History We Should Know More About.Fair Winds; 2009.ISBN1-59233-375-3.p. 54.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- ^abcWeb Japan.Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.National Flag and Anthem[PDF]; 2000 [archived15 June 2010].

- ^Edgington 2003,pp. 123–124

- ^Dyer 1909,p. 24

- ^Ashkenazi 2003,pp. 112–113

- ^Hall 1996,p. 110

- ^Sâm hạo nhất trứ “Nhật bổn thần thoại の khảo cổ học” ( triều nhật tân văn xuất bản 1993 niên 7 nguyệt )

- ^“Nhật bổn cổ điển văn học đại hệ 2 phong thổ ký” ( nham ba thư điếm 1958 niên 4 nguyệt ) の y thế quốc phong thổ ký dật văn に, thần võ thiên hoàng がY thế quốc tạoの tổ の thiên nhật biệt mệnh に mệnh じてY thế quốcに công め込ませ, quốc tân thần のY thế tân ngạnを truy い xuất して y thế を bình định したとある.

- ^Hùng dã からでは bắc に hướng かって chiến う sự になる. このためLinh mộc chân niênのように, y thế まで hành って tây からĐại hòa bồn địaに xâm công したとする thuyết もある.

- ^Tuyền hân thất lang, thiên điền kiện cộng biên 『 nhật bổn なんでもはじめ』ナンバーワン, 1985 niên, 149 hiệt,ISBN4931016065

- ^abcdefghijklQuốc kỳ “Nhật の hoàn” のルーツは “Chủng tử đảo gia の thuyền tặng”(PDF).Nishinomote City.28 January 2021. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 28 July 2021.

- ^abItoh 2003,p. 205

- ^Feldman 2004,pp. 151–155

- ^abcHongo, Jun.Hinomaru, 'Kimigayo' express conflicts both past and future.The Japan Times.17 July 2007 [archived18 July 2012].

- ^Turnbull 2001

- ^Goodman, Neary 1996,pp. 77–78

- ^National Diet Library.レファレンス sự lệ tường tế [Reference Case Details];2 July 2009 [archived20 July 2011]. Japanese.

- ^Feiler 2004,p. 214

- ^abOhnuki-Tierney 2002,pp. 68–69

- ^Rohl 2005,p. 20

- ^abcdefBefu 1992,pp. 32–33

- ^abcBefu 2001,pp. 92–95

- ^Nornes 2003,p. 81

- ^Cwiertka 2007,pp. 117–119

- ^Partner 2004,pp. 55–56

- ^Tipton 2002,p. 137

- ^Newell 1982,p. 28

- ^The Camera Overseas: The Japanese People Voted Against Frontier Friction.Life.21 June 1937 [archived13 August 2024; Retrieved 4 January 2022]:75.

- ^National Historical Institute.The Controversial Philippine National Flag[PDF]; 2008 [archived1 June 2009].

- ^Taylor 2004,p. 321

- ^Goodman, Neary 1996,p. 102

- ^Morita, D. (19 April 2007) "A Story of Treason", San Francisco:Nichi Bei Times.

- ^Ebrey 2004,p. 443

- ^Hauser, Ernest.Son of Heaven.Life.10 June 1940 [archived14 December 2011]:79.

- ^abMinistry of Education.Quốc kỳ, quốc ca の do lai đẳng [Origin of the National Flag and Anthem];1 September 1999 [archived10 January 2008]. Japanese.

- ^abcdeGoodman, Neary 1996,pp. 81–83

- ^abcWeisman, Steven R.For Japanese, Flag and Anthem Sometimes Divide.The New York Times.29 April 1990 [archived24 May 2013].

- ^Hardarce, Helen; Adam L. Kern.New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan.Brill; 1997.ISBN90-04-10735-5.p. 653.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- ^Cát điền đằng nhân.Bang nhân thuyền viên tiêu diệt [Kunihito crew extinguished][archived9 December 2012]. Japanese.

- ^University of Leicester.The Journal of Transport History.Manchester, United Kingdom: University of Leicester; 1987. p. 41.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- ^Carr, Hulme 1956,p. 200

- ^Yoshida, Shigeru. National Diet Library.Letter from Shigeru Yoshida to General MacArthur dated May 2, 1947;2 May 1947 [archived8 December 2008]. Japanese, English.

- ^MacArthur, Douglas. National Archives of Japan.Letter from Douglas MacArthur to Prime Minister dated May 2, 1947;2 May 1947 [archived11 June 2011].

- ^Meyer 2009,p. 266

- ^Large 1992,p. 184

- ^Yamazumi 1988,p. 76

- ^Fukiura, Tadamasa (2009).ブラックマヨネーズ(TV). Japan: New Star Creation.

- ^abBorneman 2003,p. 112

- ^Chira, Susan.Hirohito, 124th Emperor of Japan, Is Dead at 87.The New York Times.7 January 1989 [archived7 January 2010].

- ^Kataoka 1991,p. 149

- ^Aspinall 2001,p. 126

- ^Vote in Japan Backs Flag and Ode as Symbols.The New York Times.23 July 1999 [archived1 June 2013].

- ^Williams 2006,p. 91

- ^abcItoh 2003,pp. 209–210

- ^Goodman, Neary 1996,pp. 82–83

- ^Education: Tanaka v. the Teachers.Time.17 June 1974 [archived23 June 2011].

- ^Okano 1999,p. 237

- ^Democratic Party of Japan.Quốc kỳ quốc ca pháp chế hóa についての dân chủ đảng の khảo え phương [The DPJ Asks For A Talk About the Flag and Anthem Law];21 July 1999 [archived8 July 2013]. Japanese.

- ^Contemporary Japanese Thought.Columbia University Press; 2005.ISBN978-0-231-13620-4.p. 211.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- ^Democratic Party of Japan.Quốc kỳ ・ quốc ca pháp án, chúng viện で khả quyết dân chủ đảng は tự chủ đầu phiếu [Flag and Anthem Law Passed by the House, DPJ Free Vote];22 July 1999 [archived19 October 2013]. Japanese.

- ^National Diet Library.Đệ 145 hồi quốc hội bổn hội nghị đệ 47 hào;22 July 1999 [archived14 July 2012]. Japanese.

- ^House of Representatives.Nghị án thẩm nghị kinh quá tình báo: Quốc kỳ cập び quốc ca に quan する pháp luật án;13 August 1999 [archived23 March 2011]. Japanese.

- ^【 nhật bổn の nghị luận 】 nhật の hoàn tài đoạn による dân chủ đảng kỳ vấn đề quốc kỳ の vũ nhục hành vi への phạt tắc は thị か phi か [(Japan) Discussion of penalties of acts of contempt against the Hinomaru by the DPJ].Sankei Shimbun.30 August 2009 [archived2 September 2009]. Japanese. Sankei Digital.

- ^Minh trị 3 niên thái chính quan bố cáo đệ 57 hào

- ^Takenaka 2003,pp. 68–69

- ^abMinh trị 3 niên thái chính quan bố cáo đệ 651 hào

- ^Takenaka 2003,p. 66

- ^Cabinet Office, Government of Japan.National Flag & National Anthem;2006 [archived22 May 2009].

- ^abcMinistry of Defense.Defense Specification Z 8701C (DSPZ8701C)[PDF]; 27 November 1973 [archived20 April 2012]. Japanese.

- ^abOffice of Developmental Assistance.Nhật chương kỳ のマーク, ODAシンボルマーク [National flag mark, ODA Symbol][PDF]; 1 September 1995 [archived28 September 2011]. Japanese.

- ^National Diet Library.Đệ 145 hồi quốc hội quốc kỳ cập び quốc ca に quan する đặc biệt ủy viên hội đệ 4 hào [145th Meeting of the Diet, Discussion about the billLaw Regarding the National Flag and National Anthem];2 August 1999 [archived19 August 2011]. Japanese.

- ^abHexadecimal obtained by placing the colors inFeelimage AnalyzerArchived25 January 2010 at theWayback Machine

- ^DIC Corporation.DICカラーガイド tình báo kiểm tác (ver 1.4) [DIC Color Guide Information Retrieval (version 1.4)].Japanese.[permanent dead link]

- ^Web Japan.Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Quốc kỳ と quốc ca [National Flag and Anthem][PDF] [archived5 June 2011]. Japanese.

- ^Yoshida, Shigeru. House of Councillors.Đáp biện thư đệ cửu hào;27 April 1954 [archived22 January 2010]. Japanese.

- ^47news.JR cửu châu, nhật の hoàn を yết dương へ hữu nhân 330 dịch, chúc nhật に [JR Kyushu 330 manned stations to hoist the national flag];26 November 2002 [archived8 December 2008]. Japanese.

- ^"Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan".Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2013.Retrieved27 December2012.

- ^City of Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture.Khai thôi trung の bình hòa tư liêu quán thâu tàng phẩm triển から “Nhật の hoàn ký せ thư き” について [Museum collections from the exhibition "Group flag efforts" being held for peace][archived13 August 2011]. Japanese.

- ^abSmith 1975,p. 171

- ^McBain, Roger.Going back home.Courier & Press.9 July 2005 [archived21 July 2011].

- ^Takenaka 2003,p. 101

- ^Tây cung thị lập hương thổ tư liêu quán の xí họa triển kỳ.Archived fromthe originalon 19 June 2008.Retrieved24 October2019.

- ^"Hachimaki – Japanese Headbands – DuncanSensei Japanese".DuncanSensei Japanese.24 March 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2016.Retrieved19 March2016.

- ^Cutler 2001,p. 271

- ^Spacey, John (24 January 2014)."Japan's Patriotic Bento Box (Hinomaru)".Japan Talk.Archived fromthe originalon 7 August 2017.Retrieved24 October2019.

- ^Asahi Research.TV Asahi.Quốc kỳ ・ quốc ca pháp chế hóa について [About the Law of the Flag and Anthem];18 July 1999 [archived23 May 2008]. Japanese.

- ^Hoso Bunka Foundation.テレビニュースの đa dạng hóa により, dị なる phiên tổ の cố định thị thính giả gian に sinh じる ý kiến の soa [Diversity of television news, viewers differences of opinion arise between different programs][PDF]; 2002 [archived28 February 2008]. Japanese.

- ^Khan 1998,p. 190

- ^"Town eyes subsidy for residents to buy flag".The Japan Times.Archivedfrom the original on 16 October 2012.Retrieved27 December2012.

- ^Wundunn, Sheryl.Yomitan Journal: A Pacifist Landlord Makes War on Okinawa Bases.The New York Times.11 November 1995 [archived10 December 2008].

- ^Smits, Gregory. Penn State University.Okinawa in Postwar Japanese Politics and the Economy;2000 [archived30 May 2013].

- ^"Hinomaru flies at Naha for first time in 29 years".The Japan Times.[dead link]

- ^Japan's Neo-Nationalism: The Role of the Hinomaru and Kimigayo Legislation.JPRI working paper.2001–2007 [archived28 April 2014];79:16.

- ^Lauterpacht 2002,p. 599

- ^Inoguchi, Jain 2000,p. 228

- ^Ministry of Foreign Affairs.プロトコール [Protocol][PDF]; 2009–2002 [archived6 February 2011]. Japanese.

- ^Quốc kỳ cập び quốc ca の thủ tráp いについて

- ^Quốc kỳ cập び huyện kỳ の thủ tráp いについて

- ^Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Page 1 “グローカル thông tín” bình thành 21 niên 5 nguyệt hào プロトコール giảng tọa [Protocol Question and Answer (May 2009)][PDF]; 2009–2005 [archived7 June 2011]. Japanese.

- ^Đại chính nguyên niên các lệnh đệ nhất hào

- ^Office of the Cabinet.National Diet Library.Toàn quốc chiến một giả truy điệu thức の thật thi に quan する kiện;14 May 1963 [archived10 March 2005]. Japanese.

- ^Trevor 2001,p. 78

- ^Hiroshima Prefectural Board of Education Secretariat.Học tập chỉ đạo yếu lĩnh における quốc kỳ cập び quốc ca の thủ tráp い [Handling of the flag and anthem in the National Curriculum];11 September 2001 [archived22 July 2011]. Japanese.

- ^Ministry of Education.Tiểu học giáo học tập chỉ đạo yếu lĩnh giải thuyết xã hội biên, âm lặc biên, đặc biệt hoạt động biên [National Curriculum Guide: Elementary social notes, Chapter music Chapter Special Activities];1999 [archived19 March 2006]. Japanese.

- ^Aspinall 2001,p. 125

- ^McCurry, Justin.A touchy subject.Guardian Unlimited.5 June 2006 [archived30 August 2013]. The Guardian.

- ^The Japan Times.Ishihara's Hinomaru order called legit;5 January 2006 [archived27 December 2012].

- ^Heenan 1998,p. 206

- ^abTự vệ đội pháp thi hành lệnh

- ^"Japan to skip S. Korea fleet event over 'rising sun' flag".The Asahi Shimbun.6 October 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 6 October 2018.Retrieved7 October2018.

- ^Quốc tế, tại tuyến.Triệu vi dục đại ngôn kháng nhật võng du tẩy xoát "Quân kỳ trang sự kiện" chi nhục ( đồ ) [Zhao Wei wishes to endorse the anti-Japanese gaming scrubbing].Xinhua.11 August 2006 [archived7 July 2008]. Chinese.

- ^Hải thượng tự vệ đội kỳ chương quy tắc

- ^〇 hải thượng tự vệ đội の sử dụng する hàng không cơ の phân loại đẳng cập び đồ trang tiêu chuẩn đẳng に quan する đạt

- ^Tự vệ đội の kỳ に quan する huấn lệnh

- ^Anh tinh の sổ はかつての lục thượng tự vệ đội と đồng dạng, giai cấp ではなく bộ đội quy mô を kỳ していた.

- ^"Air Self Defense Force (Japan)".CRW Flags.Archivedfrom the original on 15 March 2016.Retrieved26 October2019.

- ^Carpenter 2004,p. 124

- ^abFujitani 1996,pp. 48–49

- ^Matoba 1901,pp. 180–181

- ^Takahashi 1903,pp. 180–181

- ^Hoàng thất nghi chế lệnh [Imperial System][archived8 December 2008]. Japanese.

- ^Government of Ehime Prefecture.Ái viện huyện のシンボル [Symbols of Ehime Prefecture];2009 [archived9 January 2008]. Japanese.

- ^Quảng đảo huyện huyện chương および huyện kỳ の chế định

- ^Government of Nagano Prefecture.Trường dã huyện の huyện chương – huyện kỳ [Flag and Emblem of Nagano Prefecture];2006 [archived18 September 2007]. Japanese.

- ^Thiên thảo thị chương

- ^abThiên thảo thị kỳ

- ^Communications Museum "Tei Park".Bưu tiện のマーク[archived2 January 2013]. Japanese.

- ^Prime Minister's Office, People's Republic of Bangladesh.People's Republic of Bangladesh Flag Rules (1972)[PDF]; 2005–2007 [archived14 July 2010].

- ^Embassy of Bangladesh in the Netherlands.Facts and Figures[archived24 July 2011].

- ^Van Fossen, Anthony B.; Centre for the Study of Australia-Asia Relations, Faculty of Asian and International Studies, Griffith University.The International Political Economy of Pacific Islands Flags of Convenience.Australia-Asia.[archived14 December 2011];66(69):53.

- ^Republic of Palau National Government.Palau Flag;18 July 2008 [archived13 November 2009].

- ^Smith 2001,p. 73

- ^Saito 1987,p. 53

- ^Tazagi 2004,p. 11

- ^Mangan 2000,p. 213

- ^Gordon 1915,pp. 217–218

Bibliography

[edit]- Ashkenazi, Michael.Handbook of Japanese Mythology.ABC-CLIO; 2003.ISBN1-57607-467-6.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Aspinall, Robert W.Teachers' Unions and the Politics of Education in Japan.State University of New York Press; 2001.ISBN0-7914-5050-3.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Befu, Harumi. Symbols of nationalism andNihonjinron.In: Goodman, Roger and Kirsten Refsing.Ideology and Practice in Modern Japan.Routledge; 1992.ISBN0-415-06102-4.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Befu, Harumi.Hegemony of Homogeneity: An Anthropological Analysis of Nihonjinron.Trans Pacific Press; 2001.ISBN978-1-876843-05-2.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Borneman, John.Death of the Father: An Anthropology of the End in Political Authority.Berghahn Books; 2003–2011.ISBN1-57181-111-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Carpenter, Ronald H.Rhetoric In Martial Deliberations And Decision Making: Cases And Consequences.University of South Carolina Press; 2004.ISBN978-1-57003-555-5.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Carr, Harold Gresham;Frederick Edward Hulme.Flags of the world.London; New York: Warne; 1956.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Cutler, Thomas.The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23–26 October 1944.Naval Institute Press; 2001.ISBN1-55750-243-9.

- Cwiertka, Katarzyna Joanna.Modern Japanese Cuisine: Food, Power and National Identity.Reaktion Books; 2007.ISBN1-86189-298-5.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Dyer, Henry.Japan in World Politics: A Study in International Dynamics.Blackie & Son Limited; 1909.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Edgington, David William.Japan at the Millennium: Joining Past and Future.UCB Press; 2003.ISBN0-7748-0899-3.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Anne Walthall; James Palais.East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History.Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing; 2004.ISBN0-547-00534-2.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Feiler, Bruce.Learning to Bow: Inside the Heart of Japan.Harper Perennial; 2004.ISBN0-06-057720-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Feldman, David.Do Elephants Jump?.HarperCollins; 2004.ISBN0-06-053913-5.

- Fujitani, Takashi.Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan.University of California Press; 1996.ISBN978-0-520-21371-5.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Goodman, Roger; Ian Neary.Case Studies on Human Rights in Japan.Routledge; 1996.ISBN978-1-873410-35-6.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Gordon, William.Flags of the World, Past and Present.Frederick Warne & Co.; 1915.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Hall, James.Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art.Westview Press; 1996.ISBN0-06-430982-7.

- Heenan, Patrick.The Japan Handbook.Routledge; 1998.ISBN1-57958-055-6.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Inoguchi, Takashi; Purnendra Jain.Japanese Foreign Policy Today.Palgrave Macmillan Ltd; 2000.ISBN0-312-22707-8.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Itoh, Mayumi.The Hatoyama Dynasty: Japanese Political Leadership Through the Generations.Palgrave Macmillan; 2003.ISBN1-4039-6331-2.

- Kataoka, Tetsuya.Creating Single-Party Democracy: Japan's Postwar Political System.Hoover Institution Press; 1991.ISBN0-8179-9111-5.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Khan, Yoshimitsu.Japanese Moral Education: Past and Present.Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; 1998.ISBN0-8386-3693-4.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Large, Stephen.Emperor Hirohito and Showa Japan: A Political Biography.Routledge; 1992.ISBN0-415-03203-2.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Lauterpacht, Elihu. In: C. J. Greenwood and A. G. Oppenheimer.International Law Reports.Cambridge University Press; 2002.ISBN978-0-521-80775-3.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Mangan, J.A.; Finn, Gerry; Giulianotti, Richard and Majumdar, Boria.Football Culture Local Conflicts, Global Visions.Routledge; 2000.ISBN978-0-7146-5041-8.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Matoba, Seinosuke.Lục quân と hải quân [Army and Navy].1901.(in Japanese).Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Meyer, Milton.Japan: A Concise History.Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group; 2009.ISBN0-7425-4117-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Newell, William.Japan in Asia: 1942–1945.Singapore University Press; 1982.ISBN9971-69-014-4.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Nornes, Abe Mark.Japanese Documentary Film The Meiji Era through Hiroshima.University of Minnesota Press; 2003.ISBN0-8166-4046-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko.Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms.University of Chicago Press; 2002.ISBN978-0-226-62091-6.

- Okano, Kaori; Motonori Tsuchiya (1999),Education in Contemporary Japan,Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-0-521-62686-6,archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2024,retrieved17 October2020

- Partner, Simon.Toshié A Story of Village Life in Twentieth-Century Japan.University of California Press; 2004.ISBN978-0-520-24097-1.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Röhl, Wilhelm.History of law in Japan since 1868, Part 5, Volume 12.Brill; 2005.ISBN978-90-04-13164-4.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Saito, Shinya.Ký giả tứ thập niên [Fourteen Years As A Reporter].Asahi Shimbun Publishing; 1987.(in Japanese).ISBN978-4-02-260421-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Smith, Whitney.Flags Through the Ages and Across the World.McGraw-Hill; 1975.ISBN0-07-059093-1.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Smith, Whitney.Flag Lore Of All Nations.Millbrook Press; 2001.ISBN0-7613-1753-8.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Takahashi, Yuuichi.Hải quân vấn đáp [Navy Dialogue].1903.(in Japanese).Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Takenaka, Yoshiharu.Tri っておきたい quốc kỳ ・ kỳ の cơ sở tri thức [Flag basics you should know].Gifu Shimbun; 2003.(in Japanese).ISBN4-87797-054-1.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman.Indonesia: Peoples and Histories.Yale University Press; 2004.ISBN0-300-10518-5.

- Tazagi, Shirou.Vĩ sơn tĩnh lục: Tử に nhan に tiếu みをたたえて [Seiroku Kajiyama: Praising the smile in the dying face].Kodansha; 2004.(in Japanese).ISBN4-06-212592-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Tipton, Elise.Modern Japan A Social and Political History.Routledge; 2002.ISBN978-0-415-18538-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Trevor, Malcolm.Japan – Restless Competitor The Pursuit of Economic Nationalism.Routledge; 2001.ISBN978-1-903350-02-7.Archived13 August 2024 at theWayback Machine

- Turnbull, Stephen; Howard Gerrard.Ashigaru 1467–1649.Osprey Publishing; 2001.ISBN1-84176-149-4.

- Williams, David; Rikki Kersten (2006),The Left in the Shaping of Japanese Democracy,Routledge,ISBN978-0-415-33435-8,archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2024,retrieved17 October2020

- Yamazumi, Masami.Nhật の hoàn ・ quân が đại vấn đề とは hà か.Otsuki Shoten; 1988.(in Japanese).ISBN4-272-41032-6.

Legislation

[edit]- Government of Japan.Minh trị 3 niên thái chính quan bố cáo đệ 57 hào [Prime Minister's Proclamation No. 57];27 February 1870 [archived23 May 2013].(in Japanese).

- National Diet Library.Minh trị 3 niên thái chính quan bố cáo đệ 651 hào [Prime Minister's Proclamation No. 651][PDF]; 3 October 1870 [archived20 October 2021].(in Japanese).

- Government of Japan.Đại chính nguyên niên các lệnh đệ nhất hào ( đại tang trung ノ quốc kỳ yết dương phương ) [Regulation 1 from 1912 (Raising Mourning Flag For the Emperor)];30 July 1912 [archived18 August 2010].(in Japanese).

- Government of Japan.Tự vệ đội pháp thi hành lệnh [Self-Defense Forces Law Enforcement Order];30 June 1954 [archived7 April 2008].(in Japanese).

- Ministry of Defense.〇 hải thượng tự vệ đội の sử dụng する hàng không cơ の phân loại đẳng cập び đồ trang tiêu chuẩn đẳng に quan する đạt [Standard Sizes, Markings and Paint Used On Aircraft][PDF]; 24 December 1962 [archived22 July 2011].(in Japanese).

- Government of Hiroshima Prefecture.Quảng đảo huyện huyện chương および huyện kỳ の chế định [Law About the Flag and Emblem of Hiroshima Prefecture];16 July 1968 [archived19 July 2011].(in Japanese).

- Government of Japan.Quốc kỳ cập び quốc ca に quan する pháp luật ( pháp luật đệ bách nhị thập thất hào ) [Law Regarding the National Flag and National Anthem, Act No. 127];13 August 1999 [archived21 May 2010].(in Japanese).

- Police of the Hokkaido Prefecture.Quốc kỳ cập び quốc ca の thủ tráp いについて [Law Regarding Use of the National Flag and Anthem];18 November 1999 [archived6 May 2008].(in Japanese).

- Police of Kanagawa Prefecture.Quốc kỳ cập び huyện kỳ の thủ tráp いについて [Law Regarding the Use of the National and Prefectural Flag][PDF]; 29 March 2003 [archived4 October 2011].(in Japanese).

- Government of Amakusa City.Thiên thảo thị chương [Emblem of Amakusa];27 March 2003 [archived30 September 2013].(in Japanese).

- Government of Amakusa City.Thiên thảo thị kỳ [Flag of Amakusa];27 March 2003 [archived28 September 2013].(in Japanese).

- Ministry of Defense.Tự vệ đội の kỳ に quan する huấn lệnh [Flag Rules of the JASDF][PDF]; 25 March 2008 [archived22 July 2011].(in Japanese).

- Ministry of Defense.Hải thượng tự vệ đội kỳ chương quy tắc [JMSDF Flag and Emblem Rules][PDF]; 25 March 2008 [archived22 July 2011].(in Japanese).