Hitomi(satellite)

Artist depiction ofHitomisatellite | |||||||||||

| Names | ASTRO-H New X-ray Telescope (NeXT) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | X-ray astronomy | ||||||||||

| Operator | JAXA | ||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 2016-012A | ||||||||||

| SATCATno. | 41337 | ||||||||||

| Mission duration | 3 years (planned) ≈37 days and 16 hours (achieved) | ||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||

| Launch mass | 2,700 kg (6,000 lb)[1] | ||||||||||

| Dimensions | Length: 14 m (46 ft) | ||||||||||

| Power | 3500watts | ||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||

| Launch date | 17 February 2016, 08:45UTC[2] | ||||||||||

| Rocket | H-IIA202, No. 30 | ||||||||||

| Launch site | Tanegashima Space Center | ||||||||||

| End of mission | |||||||||||

| Disposal | Destroyed on orbit | ||||||||||

| Destroyed | 26 March 2016, ≈01:42 UTC[3] | ||||||||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||||||||

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit[4] | ||||||||||

| Regime | Low Earth orbit | ||||||||||

| Perigee altitude | 559.85 km (347.87 mi) | ||||||||||

| Apogee altitude | 581.10 km (361.08 mi) | ||||||||||

| Inclination | 31.01° | ||||||||||

| Period | 96.0 minutes | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

X-ray astronomy satellitein Japan | |||||||||||

Hitomi(Japanese:ひとみ),also known asASTRO-HandNew X-ray Telescope(NeXT), was anX-ray astronomysatellite commissioned by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) for studying extremely energetic processes in theUniverse.The space observatory was designed to extend the research conducted by theAdvanced Satellite for Cosmology and Astrophysics(ASCA) by investigating the hard X-ray band above 10keV.The satellite was originally called New X-ray Telescope;[5]at the time of launch it was called ASTRO-H.[6]After it was placed in orbit and itssolar panelsdeployed, it was renamedHitomi.[7]The spacecraft was launched on 17 February 2016 and contact was lost on 26 March 2016, due to multiple incidents with theattitude controlsystem leading to an uncontrolled spin rate and breakup of structurally weak elements.[8]

Name

[edit]The new name refers to thepupil of an eye,and to a legend of a painting of four dragons.[6]The word Hitomi generally means "eye",and specifically thepupil,or entrance window of the eye – the aperture. There is also an ancient legend that inspires the name Hitomi. "One day, many years ago, a painter was drawing four white dragons on a street. He finished drawing the dragons, but without" Hitomi ". People who looked at the painting said" why don't you paint Hitomi, it is not complete. The painter hesitated, but people pressured him. The painter then drew Hitomi on two of the four dragons. Immediately, these dragons came to life and flew up into the sky. The two dragons without Hitomi remained still ". The inspiration of this story is that Hitomi is regarded as the" One last, but most important part ", and so we wish ASTRO-H to be the essential mission to solve mysteries of the universe in X-rays. Hitomi refers to the aperture of the eye, the part where incoming light is absorbed. From this, Hitomi reminds us of a black hole. We will observe Hitomi in the Universe using the Hitomi satellite.[9]

Objectives

[edit]Hitomi'sobjectives were to explore the large-scale structure and evolution of the universe, as well as the distribution of dark matter within galaxy clusters[10]and how the galaxy clusters evolve over time;[6]how matter behaves in strong gravitational fields[10](such as matter inspiraling into black holes),[6]to explore the physical conditions in regions where cosmic rays are accelerated,[10]as well as observing supernovae.[6]In order to achieve this, it was designed to be capable of:[10]

- Imaging andspectroscopicmeasurements with a hardX-ray telescope;[10]

- Spectroscopic observations with an extremely high energy resolution using the micro-calorimeter;[10]

- Sensitive wideband observations over the energy range 0.3-600 keV.[10]

It was the sixth of a series of JAXA X-ray satellites,[10]which started in 1979,[7]and it was designed to observe sources that are an order of magnitude fainter than its predecessor,Suzaku.[6]Its planned mission length was three years.[7]At the time of launch, two other large X-ray satellites were carrying out observations in orbit: theChandra X-ray ObservatoryandXMM-Newton,both of which were launched in 1999.[6]

Instruments

[edit]The probe carried four instruments and six detectors to observe photons with energies ranging from softX-raystogamma rays,with a high energy resolution.[10][7]Hitomiwas built by an international collaboration led by JAXA with over 70 contributing institutions in Japan, the United States, Canada, and Europe,[10]and over 160 scientists.[11]With a mass of 2,700 kg (6,000 lb),[10][7]At launch,Hitomiwas the heaviest Japanese X-ray mission.[1]The satellite is about 14 m (46 ft) in length.[7]

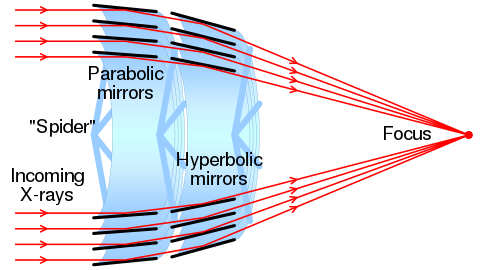

Two soft X-ray telescopes (SXT-S, SXT-I), with focal lengths of 5.6 m (18 ft), focus light onto a soft X-ray Spectrometer (SXS), provided byNASA,with an energy range of 0.4–12 keV for high-resolutionX-ray spectroscopy,[10]and a soft X-ray imager (SXI), with an energy range of 0.3–12 keV.[10]

Two hard X-ray telescopes (HXT), with a focus length of 12 m (39 ft),[10][12]focus light onto two hard X-ray imagers (HXI),[10]with energy range 5-80 keV,[12]which are mounted on a plate placed at the end of the 6 m (20 ft) extendable optical bench (EOB) that is deployed once the satellite is in orbit.[10]TheCanadian Space Agency(CSA) provided the Canadian ASTRO-H Metrology System (CAMS),[13][14]which is a laser alignment system that will be used to measure the distortions in the extendible optical bench.

Two soft Gamma-ray detectors (SGD), each containing three units, were mounted on two sides of the satellite, using non-focusing detectors to observe soft gamma-ray emission with energies from 60 to 600 KeV.[1][10]

TheNetherlands Institute for Space Research(SRON) in collaboration with theUniversity of Genevaprovided the filter-wheel and calibration source for thespectrometer.[15][16]

-

Focusing X-rays with a Wolter Type-1 optical system

-

Soft X-ray mirror assembled by NASA

-

Microcalorimeter array of the Soft X-ray Spectrometer. The five-millimeter square forms a 36-pixel array. Each pixel is 0.824 millimeter on a side. The detector’s field of view is approximately three arcminutes.

Launch

[edit]The launch of the satellite was planned for 2013 as of 2008,[17]later revised to 2015 as of 2013.[11]As of early February 2016, it was planned for 12 February, but was delayed due to poor weather forecasts.[18]

Hitomilaunched on 17 February 2016 at 08:45UTC[6][7]into alow Earth orbitof approximately 575 km (357 mi).[10]The circular orbit had anorbital periodof around 96 minutes, and anorbital inclinationof 31.01°.[10]It was launched from theTanegashima Space Centeron board anH-IIAlaunch vehicle.[10][6]14 minutes after launch, the satellite separated from the launch vehicle. The solar arrays later deployed according to plan, and it began its on-orbit checkout.[6]

Operations

[edit]Measurements by Hitomi have allowed scientists to track the motion of X-ray-emitting gas at the heart of the Perseus cluster of galaxies for the first time. Using the Soft X-ray Spectrometer, astronomers have mapped the motion of X-ray-emitting gas in a cluster of galaxies and shown it moves at cosmically modest speeds. The total range of gas velocities directed toward or away from Earth within the area observed byHitomiwas found to be about 365,000 miles an hour (590,000 kilometers per hour). The observed velocity range indicates that turbulence is responsible for only about 4 percent of the total gas pressure.[19]

-

Map of the motion of hot X-ray-emitting gas in the Perseus galaxy cluster. The square overlay, which spans about 195,000 light-years at the cluster's distance, shows the area observed byHitomi.

-

The X-ray spectrum observed byHitomi's Soft X-ray Imaging Spectrometer (SXS) reveals details of the million-degree gas filling the Perseus galaxy cluster.

Loss of spacecraft

[edit]On 27 March 2016,JAXAreported that communication withHitomihad "failed from the start of its operation" on 26 March 2016 at 07:40 UTC.[20]On the same day, the U.S.Joint Space Operations Center(JSpOC) announced onTwitterthat it had observed a breakup of the satellite into 5 pieces at 08:20 UTC on 26 March 2016,[21]and its orbit also suddenly changed on the same day.[22]Later analysis by the JSpOC found that the fragmentation likely took place around 01:42 UTC, but that there was no evidence the spacecraft had been struck by debris.[3]Between 26 and 28 March 2016, JAXA reported receiving three brief signals fromHitomi;while the signals were offset by 200 kHz from what was expected fromHitomi,their direction of origin and time of reception suggested they were legitimate.[23]Later analysis, however, determined that the signals were not fromHitomibut from an unknown radio source not registered with theInternational Telecommunication Union.[23][24]

JAXA stated they were working to recover communication and control over the spacecraft,[20]but that "the recovery will require months, not days".[25]Initially suggested possibilities for the communication loss is that a helium gas leak, battery explosion, or stuck-open thruster caused the satellite to start rotating, rather than a catastrophic failure.[22][26][27]JAXA announced on 1 April 2016 thatHitomihad lost attitude control at around 19:10 UTC on 25 March 2016. After analysing engineering data from just before the communication loss, however, no problems were noted with either the helium tank or batteries.[28]

The same day, JSpOC released orbital data for ten detected pieces of debris, five more than originally reported, including one piece that was large enough to initially be confused with the main body of the spacecraft.[29][30]Amateur trackers observed what was believed to beHitomitumbling in orbit, with reports of the main spacecraft body (Object A) rotating once every 1.3 or 2.6 seconds, and the next largest piece (Object L) rotating every 10 seconds.[30]

JAXA ceased efforts to recover the satellite on 28 April 2016, switching focus to anomaly investigation.[24][31]It was determined that the chain of events that led to the spacecraft's loss began with itsinertial reference unit(IRU) reporting a rotation of 21.7° per hour at 19:10 UTC on 25 March 2016, though the vehicle was actually stable. Theattitude controlsystem attempted to useHitomi'sreaction wheelsto counteract the non-existent spin, which caused the spacecraft to rotate in the opposite direction. Because the IRU continued to report faulty data, the reaction wheels began to accumulate excessive momentum, tripping the spacecraft's computer into taking the vehicle into "safe hold" mode. Attitude control then tried to use its thrusters to stabilise the spacecraft; theSun sensorwas unable to lock on to the Sun's position, and continued thruster firings causedHitomito rotate even faster due to an incorrect software setting. Because of this excessive rotation rate, early on 26 March 2016 several parts of the spacecraft broke away, likely including both solar arrays and the extended optical bench.[8][23]

Replacement

[edit]Reports of aHitomireplacement mission first surfaced on 21 June 2016.[32]According to an article fromKyodo News,JAXA was considering a launch of "Hitomi 2" in the early 2020s aboard Japan's newH3 launch vehicle.[32]The spacecraft would be a near-copy ofHitomi.[32]However, a 27 June 2016 article fromThe Nikkeistated that some within theMinistry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technologybelieved it was too early to grant funding for aHitomireplacement.[33]The article also noted thatNASAhad expressed support for a replacement mission led by Japan.

On 14 July 2016, JAXA published a press release regarding the ongoing study of a successor.[34]According to the press release, the spacecraft would be a remanufacture but with countermeasures reflectingHitomi'sloss, and would be launched in 2020 on aH-IIAlaunch vehicle. The scientific mission of the "ASTRO-H Successor" would be based around theSXSinstrument.[34]The Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology,Hiroshi Hase,stated during a press conference on 15 July 2016 that funding forHitomi'ssuccessor will be allocated in the fiscal year 2017 budget request,[35]and that he intends to accept the successor mission on the condition that the investigation ofHitomi'sdestruction is completed and measures to prevent recurrence are done accordingly.[36]TheX-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission(XRISM) was approved byJAXAandNASAin April 2017, and successfully launched in September 2023.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abc"Insight into the Hot Universe: X-ray Astronomy Satellite ASTRO-H"(PDF).JAXA. November 2015.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^Graham, William (17 February 2016)."Japanese H-IIA rocket launches ASTRO-H mission".NASASpaceFlight.com.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^abGruss, Mike (29 March 2016)."U.S. Air Force: No evidence malfunctioning Japanese satellite was hit by debris".SpaceNews.Retrieved5 April2016.

- ^"ASTRO H – Orbit".Heavens Above. 27 March 2016.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^"Hitomi (ASTRO-H)".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon 29 July 2016.Retrieved27 March2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^abcdefghijWall, Mike (17 February 2016)."Japan Launches X-Ray Observatory to Study Black Holes, Star Explosions".SPACE.com.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^abcdefg"Successful launch of Hitomi".University of Cambridge. 17 February 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 25 February 2021.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^abClark, Stephen (18 April 2016)."Attitude control failures led to break-up of Japanese astronomy satellite".Spaceflight Now.Retrieved21 April2016.

- ^"X-ray Astronomy Satellite (ASTRO-H) Solar Array Paddles Deployment and Name Decided".JAXA. 16 February 2016.Retrieved7 March2021.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrst"Astro-H – Overview".JAXA. 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 23 December 2016.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^ab"The ASTRO-H X-ray observatory"(PDF).JAXA. March 2013.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^ab"ASTRO-H – Hard X-ray Imaging System".JAXA. 2015. Archived fromthe originalon 28 June 2016.Retrieved29 October2015.

- ^"The Canadian ASTRO-H Metrology System".Saint Mary's University.

- ^"Canada Partners on Japanese X-ray Space Observatory".Canadian Space Agency. 3 August 2011.

- ^"SRON – ASTRO-H".Netherlands Institute for Space Research. 2010.Retrieved31 March2010.

- ^"European Science Support Centre for Hitomi".University of Geneva. Archived fromthe originalon 12 March 2016.Retrieved31 March2010.

- ^"NASA Selects Explorer Mission of Opportunity Investigations".NASA. 20 June 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 26 June 2008.Retrieved23 June2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^"Launch of Japanese X-ray observatory postponed".Spaceflight Now. 11 February 2016.

- ^"NASA Scientific Visualization Studio | Hitomi Measures X-ray Winds of the Perseus Galaxy Cluster".SVS.6 July 2016.Retrieved9 September2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain.

- ^ab"Communication failure of X-ray Astronomy Satellite" Hitomi "(ASTRO-H)".JAXA. 27 March 2016.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^Joint Space Operations Center [@18SPCS] (27 March 2016)."JSpOC ID'd 2 breakups..."(Tweet).Retrieved27 March2016– viaTwitter.

- ^abDrake, Nadia(27 March 2016)."Japan Loses Contact With Newest Space Telescope".No Place Like Home. National Geographic. Archived fromthe originalon 28 March 2016.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^abc"Supplemental Handout on the Operation Plan of the X-ray Astronomy Satellite ASTRO-H (Hitomi)"(PDF).JAXA. 28 April 2016.Retrieved13 June2016.

- ^ab"Japan abandons costly X-ray satellite lost in space".Associated Press. 29 April 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 13 September 2016.Retrieved29 April2016.

- ^Foust, Jeff (30 March 2016)."JAXA believes still possible to recover Hitomi".SpaceNews.Retrieved5 April2016.

- ^"Japan: Trouble Reaching Innovative New Space Satellite".ABC News. The Associated Press. 27 March 2016.Retrieved27 March2016.

- ^Misra, Ria; Ouellette, Jennifer (30 March 2016)."Japan's Lost Black Hole Satellite Just Reappeared and Nobody Knows What Happened to It".Gizmodo.Retrieved5 April2016.

- ^"Debris appeared after Hitomi failed to keep position, JAXA says".The Japan Times.Jiji Press. 2 April 2016.Retrieved5 April2016.

- ^"10 pieces from Astro-H break-up..."Twitter.com.Joint Space Operations Center. 1 April 2016.Retrieved5 April2016.

- ^ab"New Orbital Data and Observations Dim Hopes for Japanese Hitomi Spacecraft".Spaceflight101.com. 2 April 2016.Retrieved5 April2016.

- ^"Operation Plan of X-ray Astronomy Satellite ASTRO-H (Hitomi)".NASA. 28 April 2016.Retrieved28 April2016.

- ^abc"Vệ tinh “ひとみ2” đả ち thượng げへ 20 niên đại tiền bán mục tiêu に tái thiêu chiến "(in Japanese). Kyodo News. 22 June 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 16 September 2016.Retrieved18 July2016.

- ^"JAXA, “ひとみ” đại thế cơ の kiểm thảo phù thượng văn khoa tỉnh は thận trọng ".The Nikkei(in Japanese). 27 June 2016.Retrieved18 July2016.

- ^ab"X tuyến thiên văn vệ tinh ASTRO‐H “ひとみ” の hậu 継 cơ の kiểm thảo について "(PDF)(in Japanese). JAXA. 14 July 2016.Retrieved18 July2016.

- ^"Vệ tinh “ひとみ” hậu 継 cơ, 17 niên độ に khai phát trứ thủ を văn khoa tương ".The Nikkei(in Japanese). 15 July 2016.Retrieved18 July2016.

- ^"“ひとみ” hậu 継 cơ を dung nhận = khái toán yếu cầu thịnh り込む- trì văn khoa tương "(in Japanese). Jiji Press. 15 July 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 16 July 2016.Retrieved18 July2016.

- ^"Japanese H-IIA launches X-ray telescope and lunar lander".NASASpaceflight.6 September 2023.Retrieved11 September2023.

External links

[edit]- Hitomiwebsiteby JAXA

- Hitomiwebsiteby JAXA's Institute of Space and Astronautical Science

- Hitomiwebsiteby NASA