Iberian Peninsula

Native names

| |

|---|---|

Satellite image of the Iberian Peninsula | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Europe |

| Coordinates | 40°30′N4°00′W/ 40.500°N 4.000°W |

| Area | 583,254 km2(225,196 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3,478 m (11411 ft) |

| Highest point | Mulhacén |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Iberian |

| Population | c. 53million |

TheIberian Peninsula(IPA:/aɪˈbɪəriən/),[a]also known asIberia,[b]is apeninsulain south-westernEurope,defining the westernmost edge ofEurasia.Separated from the rest of the European landmass by thePyrenees,it includes the territories ofPeninsular Spain[c]andContinental Portugal,comprising most of the region, as well as the tiny adjuncts ofAndorra,the British Overseas Territory ofGibraltar,and, pursuant to the traditional definition of the Pyrenees as the peninsula's northeastern boundary, a small part ofFrance.[1]With an area of approximately 583,254 square kilometres (225,196 sq mi),[2]and a population of roughly 53 million,[3]it is the second-largest European peninsula by area, after theScandinavian Peninsula.

Etymology and Name

[edit]

Greek name

[edit]The wordIberiais a noun adapted from theLatinwordHiberiaoriginating in theAncient GreekwordἸβηρία(Ibēríā), used by Greek geographers under the rule of theRoman Empireto refer to what is known today in English as the Iberian Peninsula.[4]At that time, the name did not describe a single geographical entity or a distinct population; the same name was used for theKingdom of Iberia,natively known asKartliin theCaucasus,the core region of what would later become theKingdom of Georgia.[5]It wasStrabowho first reported the delineation ofIberiafromGaul(Keltikē) by thePyrenees[6]and included the entire land mass southwest (he says "west" ) from there.[7]With the fall of theWestern Roman Empireand the consolidation ofRomance languages,the word "Iberia" continued the Roman wordHiberiaand the Greek wordἸβηρία.

The ancient Greeks reached the Iberian Peninsula, of which they had heard from thePhoenicians,by voyaging westward on theMediterranean.[8]Hecataeus of Miletuswas the first known to use the termIberia,which he wrote aboutc. 500 BCE.[9]Herodotusof Halicarnassus says of thePhocaeansthat "it was they who made the Greeks acquainted with [...] Iberia."[10]According toStrabo,[11]prior historians usedIberiato mean the country "this side of theἾβηρος(Ibēros,theEbro) as far north as theRhône,but in his day they set thePyreneesas the limit.Polybiusrespects that limit,[12]but identifies Iberia as the Mediterranean side as far south asGibraltar,with the Atlantic side having no name. Elsewhere[13]he says thatSaguntumis "on the seaward foot of the range of hills connecting Iberia and Celtiberia."

Roman names

[edit]According to Charles Ebel, the ancient sources in both Latin and Greek useHispaniaandHiberia(Greek:Iberia) as synonyms. The confusion of the words was because of an overlapping in political and geographic perspectives. The Latin wordHiberia,similar to the GreekIberia,literally translates to "land of the Hiberians". This word was derived from the riverHiberus(now calledEbroor Ebre).Hiber(Iberian) was thus used as a term for peoples living near the river Ebro.[6][14]The first mention in Roman literature was by the annalist poetEnniusin 200 BCE.[15][16][17]Virgilwroteimpacatos (H)iberos( "restless Iberi" ) in hisGeorgics.[18]The Roman geographers and other prose writers from the time of the lateRoman Republiccalled the entire peninsulaHispania.

In Greek and Roman antiquity, the nameHesperiawas used for both the Italian and Iberian Peninsula; in the latter caseHesperia Ultima(referring to its position in the far west) appears as form of disambiguation from the former among Roman writers.[19] Also since Roman antiquity, Jews gave the nameSepharadto the peninsula.[20]

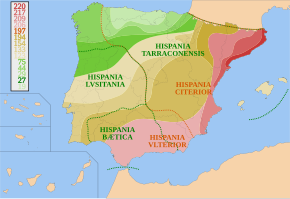

As they became politically interested in the former Carthaginian territories, the Romans began to use the namesHispania CiteriorandHispania Ulteriorfor 'near' and 'far' Hispania. At the time Hispania was made up of threeRoman provinces:Hispania Baetica,Hispania Tarraconensis,andHispania Lusitania.Strabo says[11]that the Romans useHispaniaandIberiasynonymously, distinguishing between thenearnorthern and thefarsouthern provinces. (The nameIberiawas ambiguous, being also the name of theKingdom of Iberiain the Caucasus.)

Whatever languages may generally have been spoken on the peninsula soon gave way to Latin, except for that of theVascones,which was preserved as alanguage isolateby the barrier of the Pyrenees.

Modern name

[edit]The modern phrase "Iberian Peninsula" was coined by the French geographerJean-Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincenton his 1823 work"Guide du Voyageur en Espagne".Prior to that date, geographers had used the terms 'Spanish Peninsula' or 'Pyrenaean Peninsula'.[21]

Etymology

[edit]

The Iberian Peninsula has always been associated with the RiverEbro(Ibēros inancient Greekand Ibērus or Hibērus inLatin). The association was so well known it was hardly necessary to state; for example, Ibēria was the country "this side of the Ibērus" in Strabo.Plinygoes so far as to assert that the Greeks had called "the whole of Spain" Hiberia because of the Hiberus River.[22]The river appears in theEbro Treatyof 226 BCE between Rome and Carthage, setting the limit of Carthaginian interest at the Ebro. The fullest description of the treaty, stated inAppian,[23]uses Ibērus. With reference to this border,Polybius[24]states that the "native name" isIbēr,apparently the original word, stripped of its Greek or Latin-osor-ustermination.

The early range of these natives, which geographers and historians place from the present southern Spain to the present southern France along the Mediterranean coast, is marked by instances of a readable script expressing a yet unknown language, dubbed "Iberian".Whether this was the native name or was given to them by the Greeks for their residence near the Ebro remains unknown. Credence in Polybius imposes certain limitations on etymologizing: if the language remains unknown, the meanings of the words, including Iber, must also remain unknown. In modernBasque,the wordibar[25]means "valley" or "watered meadow", whileibai[25]means "river", but there is no proof relating the etymology of the Ebro River with these Basque names.

Prehistory

[edit]Palaeolithic

[edit]The Iberian Peninsula has been inhabited by members of theHomogenus for at least 1.2 million years as remains found in the sites in theAtapuerca Mountainsdemonstrate. Among these sites is the cave ofGran Dolina,where sixhomininskeletons, dated between 780,000 and one million years ago, were found in 1994. Experts have debated whether these skeletons belong to the speciesHomo erectus,Homo heidelbergensis,or a new species calledHomo antecessor.

Around 200,000BP,during theLower Paleolithicperiod, Neanderthals first entered the Iberian Peninsula. Around 70,000 BP, during theMiddle Paleolithicperiod, the last glacial event began and the NeanderthalMousterianculture was established. Around 37,000 BP, during theUpper Paleolithic,the NeanderthalChâtelperroniancultural period began. Emanating fromSouthern France,this culture extended into the north of the peninsula. It continued to exist until around 30,000 BP, when Neanderthal man faced extinction.

About 40,000 years ago,anatomically modern humansentered the Iberian Peninsula from across the Pyrenees.[26]Haplogroup R1bis common in modernPortugueseandSpanishmales. On the Iberian Peninsula, modern humans developed a series of different cultures, such as theAurignacian,Gravettian,SolutreanandMagdaleniancultures, some of them characterized by the complex forms of theart of the Upper Paleolithic.

Neolithic

[edit]During theNeolithic expansion,variousmegalithiccultures developed in the Iberian Peninsula.[27]An open seas navigation culture from the east Mediterranean, called theCardium culture,also extended its influence to the eastern coasts of the peninsula, possibly as early as the 5th millennium BCE. These people may have had some relation to the subsequent development of theIberian civilization.

As is the case for most of the rest of Southern Europe, the principal ancestral origin of modern Iberians areEarly European Farmerswho arrived during the Neolithic. The large predominance of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R1b, common throughoutWestern Europe,is testimony to a considerable input from various waves of (predominantly male)Western Steppe Herdersfrom thePontic–Caspian steppeduring the Bronze Age. Iberia experienced a significant genetic turnover, with 100% of the paternal ancestry and 40% of the overall ancestry being replaced by peoples with steppe-related ancestry.[28]

Chalcolithic

[edit]

In theChalcolithic(c.3000 BCE), a series of complex cultures developed that would give rise to the peninsula'sfirst civilizationsand to extensive exchange networks reaching to theBaltic,Middle EastandNorth Africa.Around 2800 – 2700 BCE, theBeaker culture,which produced theMaritime Bell Beaker,probably originated in the vibrant copper-using communities of theTagusestuary and spread from there to many parts of western Europe.[29]

Bronze Age

[edit]The Bronze Age began on the Iberian Peninsula in 2100 cal. BC according to radiocarbon datings of several key sites.

Bronze Agecultures developed beginningc.1800 BCE,[30]when the culture ofLos Millareswas followed by that ofEl Argar.[31][32]During the Early Bronze Age, southeastern Iberia saw the emergence of important settlements, a development that has compelled some archeologists to propose that these settlements indicate the advent of state-level social structures.[33]From this centre, bronze metalworking technology spread to other cultures like theBronze of Levante,South-Western Iberian BronzeandLas Cogotas.

Preceded by the Chalcolithic sites of Los Millares, theArgaric cultureflourished in southeastern Iberia in from 2200 BC to 1550 BC,[34]when depopulation of the area ensued along with disappearing of copper–bronze–arsenic metallurgy.[35]The most accepted model for El Argar has been that of an early state society, most particularly in terms of class division, exploitation, and coercion,[36]with agricultural production, maybe also human labour, controlled by the larger hilltop settlements,[37]and the elite using violence in practical and ideological terms to clamp down on the population.[38]Ecological degradation, landscape opening, fires, pastoralism, and maybe tree cutting for mining have been suggested as reasons for the collapse.[39]

The culture of themotillasdeveloped an early system of groundwater supply plants (the so-calledmotillas) in the upperGuadianabasin (in the southernmeseta) in a context of extreme aridification in the area in the wake of the4.2-kiloyear climatic event,which roughly coincided with the transition from the Copper Age to the Bronze Age. Increased precipitation and recovery of the water table from about 1800 BC onward should have led to the forsaking of themotillas(which may have flooded) and the redefinition of the relation of the inhabitants of the territory with the environment.[40]

Proto-history

[edit]

By theIron Age,starting in the 8th century BCE, the Iberian Peninsula consisted of complex agrarian and urban civilizations, eitherPre-Celticor Celtic (such as theCeltiberians,Gallaeci,Astures,Celtici,Lusitaniansand others), the cultures of theIberiansin the eastern and southern zones and the cultures of theAquitanianin the western portion of the Pyrenees.

As early as the 12th century BCE, thePhoenicians,athalassocraticcivilization originally from the Eastern Mediterranean, began to explore the coastline of the peninsula, interacting with the metal-rich communities in the southwest of the peninsula (contemporarily known as the semi-mythicalTartessos).[42]Around 1100 BCE, Phoenician merchants founded the trading colony of Gadir or Gades (modern dayCádiz). Phoenicians established a permanent trading port in the Gadir colonyc. 800 BCEin response to the increasing demand of silver from theAssyrian Empire.[43]

The seafaring Phoenicians,GreeksandCarthaginianssuccessively settled along the Mediterranean coast and founded trading colonies there over several centuries. In the 8th century BCE, the firstGreek colonies,such as Emporion (modernEmpúries), were founded along the Mediterranean coast on the east, leaving the south coast to the Phoenicians.

Together with the presence of Phoenician and Greek epigraphy, severalpaleohispanic scriptsdeveloped in the Iberian Peninsula along the 1st millennium BCE. The development of a primordial paleohispanic script antecessor to the rest of paleohispanic scripts (originally supposed to be a non-redundantsemi-syllabary) derived from thePhoenician alphabetand originated in Southwestern Iberia by the 7th century BCE has been tentatively proposed.[44]

In the sixth century BCE, the Carthaginians arrived in the peninsula while struggling with the Greeks for control of the Western Mediterranean. Their most important colony was Carthago Nova (modern-dayCartagena, Spain).

History

[edit]Roman rule

[edit]

In 218 BCE, during theSecond Punic Waragainst the Carthaginians, the firstRomantroops occupied the Iberian Peninsula, known to them asHispania.After 197, the territories of the peninsula most accustomed to external contact and with the most urban tradition (the Mediterranean Coast and the Guadalquivir Valley) were divided by Romans intoHispania UlteriorandHispania Citerior.[45]Local rebellions were quelled, with a 195 Roman campaign under Cato the Elder ravaging hotspots of resistance in the northeastern Ebro Valley and beyond.[46]The threat to Roman interests posed by Celtiberians and Lusitanians in uncontrolled territories lingered in.[47]Further wars of indigenous resistance, such as theCeltiberian Warsand theLusitanian War,were fought in the 2nd century. Urban growth took place, and population progressively moved fromhillfortsto the plains.[48]

An example of the interaction ofslavingandecocide,the aftermath of the conquest increased mining extractive processes in the southwest of the peninsula (which required a massive number of forced laborers, initially from Hispania and latter also from theGallic borderlandsand other locations of the Mediterranean), bringing in a far-reaching environmental outcome vis-à-vis long-term global pollution records, with levels ofatmospheric pollutionfrom mining across the Mediterranean during Classical Antiquity having no match until the Industrial Revolution.[49][50]

In addition to mineral extraction (of which the region was the leading supplier in the early Roman world, with production of the likes of gold, silver, copper, lead, andcinnabar), Hispania also produced manufactured goods (sigillatapottery,colourless glass,linengarments) fish and fish sauce (garum), dry crops (such aswheatand, more importantly,esparto),olive oil,andwine.[51]

The process ofRomanizationspurred on throughout the first century BC.[52]The peninsula was also the battleground of civil wars between rulers of the Roman republic, such as theSertorian Waror theconflict between Caesar and Pompeylater in the century.[53]

During their 600-year occupation of the Iberian Peninsula, the Romans introduced the Latin language that influenced many of the languages that exist today in the Iberian peninsula.

Pre-modern Iberia

[edit]

In the early fifth century,Germanic peoplesoccupied the peninsula, namely theSuebi,theVandals(SilingiandHasdingi) and their allies, theAlans.Only the kingdom of the Suebi (QuadiandMarcomanni) would endure after the arrival of another wave of Germanic invaders, theVisigoths,who occupied all of the Iberian Peninsula and expelled or partially integrated the Vandals and the Alans. The Visigoths eventually occupied the Suebi kingdom and its capital city, Bracara (modern dayBraga), in 584–585. They would also occupy theprovinceof theByzantine Empire(552–624) ofSpaniain the south of the peninsula[citation needed].However,Balearic Islandsremained in Byzantine hands until Umayyad conquest, which began in 703 CE and was completed in 902 CE.[54][55]

In 711, aMuslim armyconquered theVisigothic Kingdom in Hispania.UnderTariq ibn Ziyad,the Islamic army landed at Gibraltar and, in an eight-year campaign, occupied all except the northern kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula in theUmayyad conquest of Hispania.Al-Andalus(Arabic:الإندلس,tr.al-ʾAndalūs,possibly "Land of the Vandals" ),[56][57]is the Arabic name given to Muslim Iberia. The Muslim conquerors wereArabsandBerbers;following the conquest, conversion and arabization of the Hispano-Roman population took place,[58](muwalladumorMuladí).[59][60]After a long process, spurred on in the 9th and 10th centuries, the majority of the population in Al-Andalus eventually converted to Islam.[61]The Muslims were referred to by the generic nameMoors.[62]The Muslim population was divided per ethnicity (Arabs, Berbers, Muladí), and the supremacy of Arabs over the rest of group was a recurrent causal for strife, rivalry and hatred, particularly between Arabs and Berbers.[63]Arab elites could be further divided in the Yemenites (first wave) and the Syrians (second wave).[64]Christians and Jews were allowed to live as part of a stratified society under thedhimmahsystem,[65]although Jews became very important in certain fields.[66]Some Christians migrated to the Northern Christian kingdoms, while those who stayed in Al-Andalus progressively arabised and became known asmusta'arab(mozarabs).[67]The slave population comprised theṢaqāliba(literally meaning "slavs", although they were slaves of generic European origin) as well asSudaneseslaves.[68]

The Umayyad rulers faced a majorBerber Revoltin the early 740s; the uprising originally broke out in North Africa (Tangier) and later spread across the peninsula.[69]Following theAbbasidtakeover from the Umayyads and the shift of the economic centre of the Islamic Caliphate from Damascus to Baghdad, the western province of al-Andalus was marginalised and ultimately became politically autonomous as independent emirate in 756, ruled by one of the last surviving Umayyad royals,Abd al-Rahman I.[70]

Al-Andalus became a center of culture and learning, especially during theCaliphate of Córdoba.The Caliphate reached the height of its power under the rule ofAbd-ar-Rahman IIIand his successoral-Hakam II,becoming then, in the view ofJaime Vicens Vives,"the most powerful state in Europe".[71]Abd-ar-Rahman III also managed to expand the clout of Al-Andalus across the Strait of Gibraltar,[71]waging war, as well as his successor, against theFatimid Empire.[72]

Between the 8th and 12th centuries, Al-Andalus enjoyed a notable urban vitality, both in terms of the growth of the preexisting cities as well as in terms of founding of new ones:Córdobareached a population of 100,000 by the 10th century,Toledo30,000 by the 11th century andSeville80,000 by the 12th century.[73]

During the Middle Ages, the North of the peninsula housed many small Christian polities including theKingdom of Castile,theKingdom of Aragon,theKingdom of Navarre,theKingdom of Leónor theKingdom of Portugal,as well as a number of counties that spawned from the CarolingianMarca Hispanica.Christian and Muslim polities fought and allied among themselves in variable alliances.[d]The Christian kingdoms progressively expanded south taking over Muslim territory in what is historiographically known as the "Reconquista"(the latter concept has been however noted as product of the claim to a pre-existing Spanish Catholic nation and it would not necessarily convey adequately" the complexity of centuries of warring and other more peaceable interactions between Muslim and Christian kingdoms in medieval Iberia between 711 and 1492 ").[75]

The Caliphate of Córdoba was subsumed in a period of upheaval and civil war (theFitna of al-Andalus) and collapsed in the early 11th century, spawning a series of ephemeral statelets, thetaifas.Until the mid 11th century, most of the territorial expansion southwards of the Kingdom of Asturias/León was carried out through a policy of agricultural colonization rather than through military operations; then, profiting from the feebleness of the taifa principalities,Ferdinand I of Leónseized Lamego and Viseu (1057–1058) and Coimbra (1064) away from theTaifa of Badajoz(at times at war with theTaifa of Seville);[76][77]Meanwhile, in the same year Coimbra was conquered, in the Northeastern part of the Iberian Peninsula, the Kingdom of Aragontook Barbastrofrom the HudidTaifa of Léridaas part of an international expedition sanctioned by Pope Alexander II. Most critically,Alfonso VI of León-Castileconquered Toledo and itswider taifain 1085, in what it was seen as a critical event at the time, entailing also a huge territorial expansion, advancing from theSistema CentraltoLa Mancha.[78]In 1086, following the siege of Zaragoza by Alfonso VI of León-Castile, theAlmoravids,religious zealots originally from the deserts of the Maghreb, landed in the Iberian Peninsula, and, having inflicted a serious defeat to Alfonso VI at thebattle of Zalaca,began to seize control of the remaining taifas.[79]

The Almoravids in the Iberian peninsula progressively relaxed strict observance of their faith, and treated both Jews and Mozarabs harshly, facing uprisings across the peninsula, initially in the Western part.[80]TheAlmohads,another North-African Muslim sect of Masmuda Berber origin who had previously undermined the Almoravid rule south of the Strait of Gibraltar,[81]first entered the peninsula in 1146.[82]

Somewhat straying from the trend taking place in other locations of the Latin West since the 10th century, the period comprising the 11th and 13th centuries was not one of weakening monarchical power in the Christian kingdoms.[83]The relatively novel concept of "frontier" (Sp:frontera), already reported in Aragon by the second half of the 11th century become widespread in the Christian Iberian kingdoms by the beginning of the 13th century, in relation to the more or less conflictual border with Muslim lands.[84]

By the beginning of the 13th century, a power reorientation took place in the Iberian Peninsula (parallel to the Christian expansion in Southern Iberia and the increasing commercial impetus of Christian powers across the Mediterranean) and to a large extent, trade-wise, the Iberian Peninsula reorientated towards the North away from the Muslim World.[85]

During the Middle Ages, the monarchs of Castile and León, fromAlfonso VandAlfonso VI(crownedHispaniae Imperator) toAlfonso XandAlfonso XItended to embrace an imperial ideal based on a dual Christian and Jewish ideology.[86]Despite the hegemonic ambitions of its rulers and the consolidation of the union of Castile and León after 1230, it should be pointed that, except for a brief period in the 1330s and 1340s, Castile tended to be nonetheless "essentially unstable" from a political standpoint until the late 15th century.[87]

Merchants from Genoa and Pisa were conducting an intense trading activity in Catalonia already by the 12th century, and later in Portugal.[88]Since the 13th century, theCrown of Aragonexpanded overseas; led byCatalans,it attained an overseas empire in the Western Mediterranean, with a presence in Mediterranean islands such as theBalearics,SicilyandSardinia,and even conquering Naples in the mid-15th century.[89]Genoese merchants invested heavily in the Iberian commercial enterprise with Lisbon becoming, according toVirgínia Rau,the "great centre of Genoese trade" in the early 14th century.[90]The Portuguese would later detach their trade to some extent fromGenoeseinfluence.[88]TheNasrid Kingdom of Granada,neighbouring theStrait of Gibraltarand founded upon avassalagerelationship with the Crown of Castile,[91]also insinuated itself into the European mercantile network, with its ports fostering intense trading relations with the Genoese as well, but also with the Catalans, and to a lesser extent, with the Venetians, the Florentines, and the Portuguese.[92]

Between 1275 and 1340, Granada became involved in the "crisis of the Strait", and was caught in a complex geopolitical struggle ( "a kaleidoscope of alliances" ) with multiple powers vying for dominance of the Western Mediterranean, complicated by the unstable relations of Muslim Granada with theMarinid Sultanate.[93]The conflict reached a climax in the 1340Battle of Río Salado,when, this time in alliance with Granada, the Marinid Sultan (and Caliph pretender)Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othmanmade the last Marinid attempt to set up a power base in the Iberian Peninsula. The lasting consequences of the resounding Muslim defeat to an alliance of Castile and Portugal with naval support from Aragon and Genoa ensured Christian supremacy over the Iberian Peninsula and the preeminence of Christian fleets in the Western Mediterranean.[94]

The1348–1350 bubonic plaguedevastated large parts of the Iberian Peninsula, leading to a sudden economic cessation.[95]Many settlements in northern Castile and Catalonia were left forsaken.[95]The plague marked the start of the hostility and downright violence towards religious minorities (particularly the Jews) as an additional consequence in the Iberian realms.[96]

The 14th century was a period of great upheaval in the Iberian realms. After the death ofPeter the Cruel of Castile(reigned 1350–69), theHouse of Trastámarasucceeded to the throne in the person of Peter's half brother,Henry II(reigned 1369–79). In the kingdom of Aragón, following the death without heirs ofJohn I(reigned 1387–96) andMartin I(reigned 1396–1410), a prince of the House of Trastámara,Ferdinand I(reigned 1412–16), succeeded to the Aragonese throne.[97]TheHundred Years' Waralso spilled over into the Iberian peninsula, with Castile particularly taking a role in the conflict by providing key naval support to France that helped lead to that nation's eventual victory.[98]After the accession ofHenry IIIto the throne of Castile, the populace, exasperated by the preponderance of Jewish influence, perpetrated a massacre of Jews at Toledo. In 1391, mobs went from town to town throughout Castile and Aragon, killing an estimated 50,000 Jews,[99][100][101][102][103]or even as many as 100,000, according toJane Gerber.[104]Women and children were sold as slaves to Muslims, and many synagogues were converted into churches. According toHasdai Crescas,about 70 Jewish communities were destroyed.[105]

During the 15th century, Portugal, which had ended its southwards territorial expansion across the Iberian Peninsula in 1249 with the conquest of the Algarve, initiated an overseas expansion in parallel to the rise of theHouse of Aviz,conquering Ceuta(1415) arriving atPorto Santo(1418),Madeiraand theAzores,as well as establishing additional outposts along the North-African Atlantic coast.[106]In addition, already in the Early Modern Period, between the completion of the Granada War in 1492 and the death of Ferdinand of Aragon in 1516, theHispanic Monarchywould make strides in the imperial expansion along the Mediterranean coast of the Maghreb.[107] During the Late Middle Ages, theJewsacquired considerable power and influence in Castile and Aragon.[108]

Throughout the late Middle Ages, the Crown of Aragon took part in the mediterranean slave trade, withBarcelona(already in the 14th century),Valencia(particularly in the 15th century) and, to a lesser extent,Palma de Mallorca(since the 13th century), becoming dynamic centres in this regard, involving chiefly eastern and Muslim peoples.[109]Castile engaged later in this economic activity, rather by adhering to the incipient atlantic slave trade involving sub-saharan people thrusted by Portugal (Lisbon being the largest slave centre in Western Europe) since the mid 15th century, with Seville becoming another key hub for the slave trade.[109]Following the advance in the conquest of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, the seizure ofMálagaentailed the addition of another notable slave centre for the Crown of Castile.[110]

By the end of the 15th century (1490) the Iberian kingdoms (including here the Balearic Islands) had an estimated population of 6.525 million (Crown of Castile, 4.3 million; Portugal, 1.0 million; Principality of Catalonia, 0.3 million; Kingdom of Valencia, 0.255 million; Kingdom of Granada, 0.25 million; Kingdom of Aragon, 0.25 million; Kingdom of Navarre, 0.12 million and the Kingdom of Mallorca, 0.05 million).[111]

For three decades in the 15th century, theHermandad de las Marismas,the trading association formed by the ports of Castile along the Cantabrian coast, resembling in some ways theHanseatic League,fought against the latter,[citation needed]an ally of England, a rival of Castile in political and economic terms.[112]Castile sought to claim theGulf of Biscayas its own.[113]In 1419, the powerful Castilian navythoroughly defeated a Hanseatic fleet in La Rochelle.[98][113]

In the late 15th century, the imperial ambition of the Iberian powers was pushed to new heights by theCatholic Monarchsin Castile and Aragon, and byManuel Iin Portugal.[86]

The last Muslim stronghold,Granada,was conquered by a combined Castilian and Aragonese force in 1492. As many as 100,000 Moors died or were enslaved in the military campaign, while 200,000 fled to North Africa.[114]Muslims and Jews throughout the period were variously tolerated or shown intolerance in different Christian kingdoms. After thefall of Granada,all Muslims and Jews were ordered to convert to Christianity or face expulsion—as many as 200,000 Jews wereexpelled from Spain.[115][116][117][118]Approximately 3,000,000 Muslims fled or were driven out of Spain between 1492 and 1610.[119]Historian Henry Kamen estimates that some 25,000 Jews died en route from Spain.[120]The Jews were alsoexpelled from Sicilyand Sardinia, which were under Aragonese rule, and an estimated 37,000 to 100,000 Jews left.[121]

In 1497, KingManuel I of Portugalforced all Jews in his kingdom to convert or leave. That same year heexpelledall Muslims that were not slaves,[122]and in 1502 theCatholic Monarchsfollowed suit, imposing the choice ofconversion to Christianityor exile and loss of property. Many Jews and Muslims fled toNorth Africaand theOttoman Empire,while others publicly converted to Christianity and became known respectively asMarranosandMoriscos(after the old termMoors).[123]However, many of these continued to practice their religion in secret. The Moriscos revolted several times and were ultimatelyforcibly expelledfrom Spain in the early 17th century. From 1609 to 1614, over 300,000 Moriscos were sent on ships to North Africa and other locations, and, of this figure, around 50,000 died resisting the expulsion, and 60,000 died on the journey.[124][125]

A series of case studies by theBelfer Center for Science and International AffairsatHarvard Universitydemonstrated that the change of relative supremacy from Portugal to theHispanic Monarchyin the late 15th century was one of the few cases of avoidance of theThucydides Trap.[126]

Modern Iberia

[edit]

Challenging the conventions about the advent of modernity,Immanuel Wallersteinpushed back the origins of the capitalist modernity to the Iberian expansion of the 15th century.[127]During the 16th century Spain created a vast empire in the Americas, with a state monopoly inSevillebecoming the center of the ensuing transatlantic trade, based onbullion.[128]Iberian imperialism, starting by the Portuguese establishment of routes to Asia and the posterior transatlantic trade with the New World by Spaniards and Portuguese (along Dutch, English and French), precipitated the economic decline of theItalian Peninsula.[129]The 16th century was one of population growth with increased pressure over resources;[130]in the case of the Iberian Peninsula a part of the population moved to the Americas meanwhile Jews and Moriscos were banished, relocating to other places in the Mediterranean Basin.[131]Most of the Moriscos remained in Spain after theMorisco revoltin Las Alpujarras during the mid-16th century, but roughly 300,000 of themwere expelled from the countryin 1609–1614, and emigrateden masseto North Africa.[132]

In 1580, after the political crisis that followed the 1578 death of KingSebastian,Portugal became a dynastic composite entity of the Hapsburg Monarchy; thus, the whole peninsula was united politically during the period known as theIberian Union(1580–1640). During the reign ofPhilip II of Spain(I of Portugal), the Councils of Portugal, Italy, Flanders and Burgundy were added to the group of counselling institutions of the Hispanic Monarchy, to which the Councils of Castile, Aragon, Indies, Chamber of Castile, Inquisition, Orders, and Crusade already belonged, defining the organization of the Royal court that underpinned thePolysynodial Systemthrough which the empire operated.[134]During the Iberian union, the "first great wave" of thetransatlantic slave tradehappened, according toEnriqueta Vila Villar,as new markets opened because of the unification gave thrust to the slave trade.[135]

By 1600, the percentage of urban population for Spain was roughly 11.4%, while for Portugal the urban population was estimated as 14.1%, which were both above the 7.6% European average of the time (edged only by the Low Countries and the Italian Peninsula).[136]Some striking differences appeared among the different Iberian realms. Castile, extending across a 60% of the territory of the peninsula and having 80% of the population was a rather urbanised country, yet with a widespread distribution of cities.[137]Meanwhile, the urban population in theCrown of Aragonwas highly concentrated in a handful of cities:Zaragoza(Kingdom of Aragon),Barcelona(Principality of Catalonia), and, to a lesser extent in theKingdom of Valencia,inValencia,AlicanteandOrihuela.[137]The case of Portugal presented an hypertrophied capital,Lisbon(which greatly increased its population during the 16th century, from 56,000 to 60,000 inhabitants by 1527, to roughly 120,000 by the third quarter of the century) with its demographic dynamism stimulated by the Asian trade,[138]followed at great distance byPortoandÉvora(both roughly accounting for 12,500 inhabitants).[139]Throughout most of the 16th century, both Lisbon andSevillewere among the Western Europe's largest and most dynamic cities.[140]

The 17th century has been largely considered as a very negative period for the Iberian economies, seen as a time of recession, crisis or even decline,[141]the urban dynamism chiefly moving to Northern Europe.[141]A dismantling of the inner city network in the Castilian plateau took place during this period (with a parallel accumulation of economic activity in the capital,Madrid), with onlyNew Castileresisting recession in the interior.[142]Regarding the Atlantic façade of Castile, aside from the severing of trade with Northern Europe, inter-regional trade with other regions in the Iberian Peninsula also suffered to some extent.[143]In Aragon, suffering from similar problems than Castile, the expelling of the Moriscos in 1609 in the Kingdom of Valencia aggravated the recession. Silk turned from a domestic industry into a raw commodity to be exported.[144]However, the crisis was uneven (affecting longer the centre of the peninsula), as both Portugal and the Mediterranean coastline recovered in the later part of the century by fuelling a sustained growth.[145]

The aftermath of the intermittent1640–1668 Portuguese Restoration Warbrought theHouse of Braganzaas the new ruling dynasty in the Portuguese territories across the world (barCeuta), putting an end to the Iberian Union.

Despite both Portugal and Spain starting their path towards modernization with the liberal revolutions of the first half of the 19th century, this process was, concerning structural changes in the geographical distribution of the population, relatively tame compared to what took place after World War II in the Iberian Peninsula, when strong urban development ran in parallel to substantialrural flightpatterns.[146]

Geography and geology

[edit]

The Iberian Peninsula is the westernmost of the three major southern European peninsulas—the Iberian,Italian,andBalkan.[147]It is bordered on the southeast and east by theMediterranean Sea,and on the north, west, and southwest by theAtlantic Ocean.ThePyreneesmountains are situated along the northeast edge of the peninsula, where it adjoins the rest of Europe. Its southern tip, located inTarifais the southernmost point of the European continent and is very close to the northwest coast of Africa, separated from it by theStrait of Gibraltarand theMediterranean Sea.

The Iberian Peninsula encompasses 583,254 km2and has very contrasting and uneven relief.[2]The mountain ranges of the Iberian Peninsula are mainly distributed from west to east, and in some cases reach altitudes of approximately 3000mamsl,resulting in the region having the second highest mean altitude (637 mamsl) inWestern Europe.[2]

The Iberian Peninsula extends from the southernmost extremity atPunta de Tarifato the northernmost extremity atPunta de Estaca de Baresover a distance between lines of latitude of about 865 km (537 mi) based on adegree lengthof 111 km (69 mi) per degree, and from the westernmost extremity atCabo da Rocato the easternmost extremity atCap de Creusover a distance between lines of longitude at40° N latitudeof about 1,155 km (718 mi) based on an estimated degree length of about 90 km (56 mi) for that latitude. The irregular, roughly octagonal shape of the peninsula contained within this sphericalquadranglewas compared by the geographerStrabo.[148]to an ox-hide.

About three quarters of that rough octagon is theMeseta Central,a vast plateau ranging from 610 to 760 m in altitude.[149]It is located approximately in the centre, staggered slightly to the east and tilted slightly toward the west (the conventional centre of the Iberian Peninsula has long been consideredGetafejust south ofMadrid). It is ringed by mountains and contains the sources of most of the rivers, which find their way through gaps in the mountain barriers on all sides.

Coastline

[edit]The coastline of the Iberian Peninsula is 3,313 km (2,059 mi), 1,660 km (1,030 mi) on the Mediterranean side and 1,653 km (1,027 mi) on the Atlantic side.[150]The coast has been inundated over time, with sea levels having risen from a minimum of 115–120 m (377–394 ft) lower than today at theLast Glacial Maximum(LGM) to its current level at 4,000 yearsBP.[151]The coastal shelf created by sedimentation during that time remains below the surface; however, it was never very extensive on the Atlantic side, as the continental shelf drops rather steeply into the depths. An estimated 700 km (430 mi) length of Atlantic shelf is only 10–65 km (6.2–40.4 mi) wide. At the 500 m (1,600 ft)isobath,on the edge, the shelf drops off to 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[152]

The submarine topography of the coastal waters of the Iberian Peninsula has been studied extensively in the process of drilling for oil. Ultimately, the shelf drops into theBay of Biscayon the north (an abyss), the Iberian abyssal plain at 4,800 m (15,700 ft) on the west, and Tagus abyssal plain to the south. In the north, between the continental shelf and the abyss, is an extension called the Galicia Bank, a plateau that also contains the Porto, Vigo, and Vasco da Gamaseamounts,which form the Galicia interior basin. The southern border of these features is marked byNazaré Canyon,which splits the continental shelf and leads directly into the abyss.[citation needed]

Rivers

[edit]

The major rivers flow through the wide valleys between the mountain systems. These are theEbro,Douro,Tagus,GuadianaandGuadalquivir.[153][154]All rivers in the Iberian Peninsula are subject to seasonal variations in flow.

The Tagus is the longest river on the peninsula and, like the Douro, flows westwards with its lower course in Portugal. The Guadiana river bends southwards and forms the border between Spain and Portugal in the last stretch of its course.

Mountains

[edit]The terrain of the Iberian Peninsula is largelymountainous.[155]The major mountain systems are:

- ThePyreneesand their foothills, thePre-Pyrenees,crossing the isthmus of the peninsula so completely as to allow no passage except by mountain road, trail, coastal road or tunnel.Anetoin theMaladetamassif, at 3,404 m, is the highest point

- TheCantabrian Mountainsalong the northern coast with the massivePicos de Europa.Torre de Cerredo,at 2,648 m, is the highest point

- TheGalicia/Trás-os-Montes Massifin the Northwest is made up of very old heavily eroded rocks.[156]Pena Trevinca,at 2,127 m, is the highest point

- TheSistema Ibérico,a complex system at the heart of the peninsula, in its central/eastern region. It contains a great number of ranges and divides the watershed of the Tagus, Douro and Ebro rivers.Moncayo,at 2,313 m, is the highest point

- TheSistema Central,dividing theIberian Plateauinto a northern and a southern half and stretching into Portugal (where the highest point ofContinental Portugal(1,993 m) is located in theSerra da Estrela).Pico Almanzorin theSierra de Gredosis the highest point, at 2,592 m

- TheMontes de Toledo,which also stretches into Portugal from theLa Manchanatural region at the eastern end. Its highest point, at 1,603 m, isLa Villuercain theSierra de Villuercas,Extremadura

- TheSierra Morena,which divides the watershed of the Guadiana and Guadalquivir rivers. At 1,332 m,Bañuelais the highest point

- TheBaetic System,which stretches betweenCádizand Gibraltar and northeast towardsAlicante Province.It is divided into three subsystems:

- Prebaetic System,which begins west of theSierra Sur de Jaén,reaching theMediterranean Seashores inAlicante Province.La Sagrais the highest point at 2,382 m.

- Subbaetic System,which is in a central position within the Baetic Systems, stretching fromCape TrafalgarinCádiz Provinceacross Andalusia to theRegion of Murcia.[157]The highest point, at 2,027 m (6,650 ft), is Peña de la Cruz inSierra Arana.

- Penibaetic System,located in the far southeastern area stretching between Gibraltar across the Mediterranean coastal Andalusian provinces. It includes the highest point in the peninsula, the 3,478 m highMulhacénin theSierra Nevada.[158]

Geology

[edit]

The Iberian Peninsula contains rocks of every geological period from theEdiacaranto theRecent,and almost every kind of rock is represented. World-classmineral depositscan also be found there. The core of the Iberian Peninsula consists of aHercyniancratonicblock known as theIberian Massif.On the northeast, this is bounded by the Pyrenean fold belt, and on the southeast it is bounded by theBaetic System.These twofold chains are part of theAlpine belt.To the west, the peninsula is delimited by the continental boundary formed by themagma-poor opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The Hercynian Foldbelt is mostly buried by Mesozoic and Tertiary cover rocks to the east, but nevertheless outcrops through theSistema Ibéricoand theCatalan Mediterranean System.[citation needed]

The Iberian Peninsula features one of the largestlithiumdeposits belts in Europe (an otherwise relatively scarce resource in the continent), scattered along the Iberian Massif'sCentral Iberian ZoneandGalicia Tras-Os-Montes Zone.[159]Also in the Iberian Massif, and similarly to other Hercynian blocks in Europe, the peninsula hosts someuraniumdeposits, largely located in the Central Iberian Zone unit.[160]

TheIberian Pyrite Belt,located in the SW quadrant of the Peninsula, ranks among the most importantvolcanogenicmassive sulphide districts on Earth, and it has been exploited for millennia.[161]

Climate

[edit]The Iberian Peninsula's location and topography, as well as the effects of largeatmospheric circulationpatterns induce a NW to SE gradient of yearly precipitation (roughly from 2,000 mm to 300 mm).[162]

The Iberian Peninsula has three dominant climate types. One of these is theoceanic climateseen in the northeast in which precipitation has barely any difference between winter and summer. However, most of Portugal and Spain have aMediterranean climate;thewarm-summer Mediterranean climateand thehot-summer Mediterranean climate,with various differences in precipitation and temperature depending on latitude and position versus the sea, this applies greatly to the Portuguese and Galician Atlantic coasts where, due toupwelling/downwellingphenomena average temperatures in summer can vary through as much as 10 °C (18 °F) in only a few kilometers (e.g.PenichevsSantarém) There are also more localizedsteppe climatesin central Spain, with temperatures resembling a more continental Mediterranean climate. In other extreme cases highland alpine climates such as inSierra Nevadaand areas with extremely low precipitation anddesert climatesorsemi-desert climatessuch as theAlmeríaarea,Murciaarea and southernAlicantearea.[163]In the southwestern interior of the Iberian Peninsula the hottest temperatures in Europe are found, withCórdobaaveraging around 37 °C (99 °F) in July.[164]The Spanish Mediterranean coast usually averages around 30 °C (86 °F) in summer. In sharp contrastA Coruñaat the northern tip ofGaliciahas a summer daytime high average at just below 23 °C (73 °F).[165]This cool and wet summer climate is replicated throughout most of the northern coastline. Winters in the Peninsula are for the most part, mild, although frosts are common in higher altitude areas of central Spain. The warmest winter nights are usually found indownwellingfavourable areas of the west coast, such as on capes. Precipitation varies greatly between regions on the Peninsula, in December for example the northern west coast averages above 200 mm (7.9 in) whereas the southeast can average below 30 mm (1.2 in).Insolationcan vary from just 1,600 hours in theBilbaoarea, to above 3,000 hours in theAlgarveandGulf of Cádiz.

Political divisions

[edit]

The current political configuration of the Iberian Peninsula comprises the bulk ofPortugalandSpain,the wholelandlocked microstateofAndorra,a small part of theFrench departmentofPyrénées-Orientales(French Cerdagne), and theBritish Overseas TerritoryofGibraltar.

French Cerdagne is on the south side of thePyreneesmountain range, which runs along the border between France and Spain.[166][167][168]For example, theSegreriver, which runs west and then south to meet theEbro,has its source on theFrenchside. The Pyrenees range is often considered the northeastern boundary of Iberian Peninsula, although the French coastline curves away from the rest of Europe north of the range, which is the reason whyPerpignan,which is also known as the capital ofNorthern Catalonia,is often considered as the entrance to the Iberian Peninsula.

Regarding Portugal and Spain, this chiefly excludes theMacaronesianarchipelagos (theAzoresandMadeiraof Portugal, and theCanary Islandsof Spain), theBalearic Islands(Spain), and theSpanish overseas territoriesinNorth Africa(most conspicuously the cities ofCeutaandMelilla,as well as unpopulated islets and rocks).

The countries and territories on the Iberian Peninsula:[169][170]

| Arms | Flag | Country/Territory | Capital | Area (mainland) |

Population (mainland) |

% of area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andorra | Andorra la Vella | 468 km2 (181 sq mi) |

85,863 | 0.1 | ||

| French Cerdagne (France) |

Font-Romeu-Odeillo-Via | 539 km2 (208 sq mi) |

12,035 | 0.1 | ||

| Gibraltar (United Kingdom) |

Gibraltar | 7 km2 (2.7 sq mi) |

32,688 | 0.0 | ||

| Portugal (mainland) |

Lisbon | 89,015 km2 (34,369 sq mi) |

10,142,079 | 15.3 | ||

| Spain (mainland) |

Madrid | 493,515 km2 (190,547 sq mi) |

44,493,894 | 84.5 | ||

| Total | 583,544 km2 (225,308 sq mi) |

54,766,559 | 100 | |||

Cities

[edit]The Iberian city network is dominated by three international metropolises (Barcelona,Lisbon,andMadrid) and four regional metropolises (Bilbao,Porto,Seville,andValencia).[171]The relatively weak integration of the network favours a competitive approach vis-à-vis the inter-relation between the different centres.[171]Among these metropolises, Madrid stands out within the global urban hierarchy in terms of its status as a major service centre and enjoys the greatest degree of connectivity.[172]

Major metropolitan regions

[edit]According toEurostat(2019),[173]the metropolitan regions with a population over one million are listed as follows:

| Metropolitan region | State | Population (2019) |

|---|---|---|

| Madrid | Spain | 6,641,649 |

| Barcelona | Spain | 5,575,204 |

| Lisbon | Portugal | 3,035,332 |

| Valencia | Spain | 2,540,588 |

| Seville | Spain | 1,949,640 |

| Alicante-Elche-Elda | Spain | 1,862,780 |

| Porto | Portugal | 1,722,374 |

| Málaga-Marbella | Spain | 1,660,985 |

| Murcia-Cartagena | Spain | 1,487,663 |

| Cádiz | Spain | 1,249,739 |

| Bilbao | Spain | 1,137,191 |

| Oviedo-Gijón | Spain | 1,022,205 |

Ecology

[edit]Forests

[edit]

The woodlands of the Iberian Peninsula are distinctecosystems.Although the various regions are each characterized by distinct vegetation, there are some similarities across the peninsula.

While the borders between these regions are not clearly defined, there is a mutual influence that makes it very hard to establish boundaries and some species find their optimal habitat in the intermediate areas.

The endangeredIberian lynx(Lynx pardinus) is a symbol of the Iberian mediterranean forest and of the fauna of the Iberian Peninsula altogether.[174]

A newPodarcislizard species,Podarcis virescens,was accepted as a species by the Taxonomic Committee of theSocietas Europaea Herpetologicain 2020. This lizard is native to the Iberian Peninsula and found near rivers in the region.

East Atlantic flyway

[edit]The Iberian Peninsula is an important stopover on the East Atlanticflywayfor birds migrating from northern Europe to Africa. For example,curlew sandpipersrest in the region of theBay of Cádiz.[175]

In addition to the birds migrating through, some seven million wading birds from the north spend the winter in the estuaries and wetlands of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly at locations on the Atlantic coast. InGaliciaareRía de Arousa(a home ofgrey plover), Ria deOrtigueira,Ria de Corme and Ria de Laxe. In Portugal, theAveiro LagoonhostsRecurvirostra avosetta,thecommon ringed plover,grey ploverandlittle stint.Ribatejo Provinceon theTagussupportsRecurvirostra arosetta,grey plover,dunlin,bar-tailed godwitandcommon redshank.In theSado Estuaryaredunlin,Eurasian curlew,grey plover andcommon redshank.TheAlgarvehostsred knot,common greenshankandturnstone.TheGuadalquivir Marshesregion ofAndalusiaand the Salinas deCádizare especially rich in wintering wading birds:Kentish plover,common ringed plover,sanderling,andblack-tailed godwitin addition to the others. And finally, the Ebro delta is home to all the species mentioned above.[176]

Languages

[edit]With the sole exception ofBasque,which is ofunknown origin,[177]all modern Iberian languages descend fromVulgar Latinand belong to theWestern Romance languages.[178]Throughout history (and pre-history), many different languages have been spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, contributing to the formation and differentiation of the contemporaneous languages of Iberia; however, most of them have become extinct or fallen into disuse. Basque is the onlynon-Indo-European surviving languagein Iberia and Western Europe.[179]

In modern times,Spanish(the official language of Spain, spoken by the entire 45 million population in the country, the native language of about 36 million in Europe),[180]Portuguese(the official language of Portugal, with a population over 10 million),Catalan(over 7 million speakers in Europe, 3.4 million with Catalan as first language),[181]Galician(understood by the 93% of the 2.8 million Galician population)[181]andBasque(cf. around 1 million speakers)[182]are the most widely spoken languages in the Iberian Peninsula. Spanish and Portuguese have expanded beyond Iberia to the rest of world, becomingglobal languages.

Other minority romance languages with some degree of recognition include the several varieties ofAstur-leonese,collectively amounting to about 0.6 million speakers,[183]and theAragonese(barely spoken by the 8% of the 130,000 people inhabiting theAlto Aragón).[184]

Englishis the official language of Gibraltar.Llanitois a unique language in the territory, an amalgamation of mostly English and Spanish.[185]In Spain, only 54.3% could speak a foreign language, below that of the EU-28 average. Portugal meanwhile achieved 69%, above the EU average, but still below the EU median. Spain ranks 25th out of 33 European countries in the English Proficiency Index.[186]

Transportation

[edit]Both Spain and Portugal have traditionally used a non-standard rail gauge (the 1,668 mmIberian gauge) since the construction of the first railroads in the 19th century. Spain has progressively introduced the 1,435 mmstandard gaugein its new high-speed rail network (one of the most extensive in the world),[187]inaugurated in 1992 with theMadrid–Seville line,followed to name a few by theMadrid–Barcelona(2008),Madrid–Valencia(2010), an Alicante branch of the latter (2013) and the connection to France of the Barcelona line.[188]Portugal however suspended all the high-speed rail projects in the wake of the2008 financial crisis,putting an end for the time being to the possibility of a high-speed rail connection between Lisbon, Porto and Madrid.[189]

Handicapped by a mountainous range (thePyrenees) hindering the connection to the rest of Europe, Spain (and subsidiarily Portugal) only has two meaningful rail connections to France able for freight transport, located at both ends of the mountain range.[190]An international rail line across the Central Pyrenees linkingZaragozaand the French city ofPauthrough a tunnel existed in the past; however, an accident in the French part destroyed a stretch of the railroad in 1970 and theCanfranc Stationhas been acul-de-sacsince then.[191]

There are four points connecting the Portuguese and Spanish rail networks:Valença do Minho–Tui,Vilar Formoso–Fuentes de Oñoro,Marvão-Beirã–Valencia de AlcántaraandElvas–Badajoz.[192]

The prospect of the development (as part of a European-wide effort) of the Central, Mediterranean and Atlantic rail corridors is expected to be a way to improve the competitiveness of the ports ofTarragona,Valencia,Sagunto,Bilbao,Santander,SinesandAlgecirasvis-à-vis the rest of Europe and the World.[193]

In 1980, Morocco and Spain started a joint study on the feasibility of a fixed link (tunnel or bridge) across theStrait of Gibraltar,possibly through a connection ofPunta PalomawithCape Malabata.[194]Years of studies have, however, made no real progress thus far.[195]

A transit point for many submarine cables, theFibre-optic Link Around the Globe,Europe India Gateway,and theSEA-ME-WE 3feature landing stations in the Iberian Peninsula.[196]TheWest Africa Cable System,Main One,SAT-3/WASC,Africa Coast to Europealso land in Portugal.[196]MAREA,a high capacity communication transatlantic cable, connects the north of the Iberian Peninsula (Bilbao) to North America (Virginia), whereasGrace Hopperis an upcoming cable connecting the Iberian Peninsula (Bilbao) to the UK and the US intended to be operative by 2022[197]andEllaLinkis an upcoming high-capacity communication cable expected to connect the Peninsula (Sines) to South America and the mammoth2Africa projectintends to connect the peninsula to the United Kingdom, Europe and Africa (via Portugal and Barcelona) by 2023–24.[198][199]

Two gas pipelines: thePedro Duran Farell pipelineand (more recently) theMedgaz(from, respectively, Morocco and Algeria) link the Maghreb and the Iberian Peninsula, providing Spain with Algerian natural gas.[200][201]However the contract for the first pipeline expires on 31 October 2021 and—amidst a tense climate ofAlgerian–Moroccan relations—there are no plans to renew it.[202]

Economy

[edit]The official currency across Iberia is theEuro,with the exception of Gibraltar, which uses theGibraltar Pound(at parity withSterling).[185]

Major industries include mining, tourism, small farms, and fishing. Because the coast is so long, fishing is popular, especially sardines, tuna and anchovies. Most of the mining occurs in the Pyrenees mountains. Commodities mined include: iron, gold, coal, lead, silver, zinc, and salt.

Regarding their role in the global economy, both the microstate ofAndorraand the British Overseas Territory ofGibraltarhave been described astax havens.[203]

The Galician region of Spain, in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula, became one of the biggest entry points ofcocainein Europe, on a par with the Dutch ports.[204]Hashishis smuggled fromMoroccovia theStrait of Gibraltar.[204]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^In the local languages:

- Spanish,Portuguese,Galician,Asturian,andExtremaduran:Península Ibérica(mostly rendered in lowercase in Spanish:península ibérica)

- Spanish:[peˈninsulajˈβeɾika](the same in Asturian and Extremaduran)

- Portuguese:[pɨˈnĩsulɐiˈβɛɾikɐ]

- Galician:[peˈninsʊlɐiˈβɛɾikɐ]

- Catalan:Península Ibèrica

- Catalan pronunciation:[pəˈninsuləiˈβɛɾikə]

- Aragonese:Peninsula Iberica

- Aragonese:[peninˈsulaiβeˈɾika]

- French:Péninsule Ibérique[penɛ̃sylibeʁik]

- Mirandese:Península Eibérica[pɨˈnĩsulɐejˈβɛɾikɐ]

- Basque:Iberiar penintsula[iβeɾiarpenints̺ula]

- Spanish,Portuguese,Galician,Asturian,andExtremaduran:Península Ibérica(mostly rendered in lowercase in Spanish:península ibérica)

- ^In the local languages:

- Spanish, Aragonese, Asturian, Extremaduran and Galician:Iberia

- Portuguese and Mirandese:Ibéria

- Catalan:Ibèria

- Catalan pronunciation:[iˈβɛɾiə]

- Occitan:[iˈβɛɾiɔ,-ˈbɛʀi-]

- French:Ibérie[ibeʁi]

- Basque:Iberia[iβeɾia]

- ^Thus, strictly speaking, leaving out the mainland Spanish territory of theAran Valley,in the northern Pyrenean watershed.[1]

- ^Christian forces were usually better armoured than their Muslim counterparts, with noble and non-noblemilitesandcavallerswearingmailhauberks,separatemail coifsand metal helmets, and armed withmaces,cavalry axes, sword and lances.[74]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^abde Juana, Eduardo; Garcia, Ernest (2015).The Birds of the Iberian Peninsula.Bloomsbury Publishing.p. 9.ISBN978-1-4081-2480-2.

- ^abcLorenzo-Lacruz et al. 2011,p. 2582.

- ^Triviño, María; Kujala, Heini; Araújo, Miguel B.; Cabeza, Mar (2018)."Planning for the future: identifying conservation priority areas for Iberian birds under climate change".Landscape Ecology.33(4): 659–673.Bibcode:2018LaEco..33..659T.doi:10.1007/s10980-018-0626-z.hdl:10138/309558.ISSN0921-2973.S2CID3699212.

- ^Claire L. Lyons; John K. Papadopoulos (2002).The Archaeology of Colonialism.Getty Publications. pp. 68–69.ISBN978-0-89236-635-4.

- ^Strabo."Book III Chapter 1 Section 6".Geographica.

And also the other Iberians use an alphabet, though not letters of one and the same character, for their speech is not one and the same.

- ^abCharles Ebel (1976).Transalpine Gaul: The Emergence of a Roman Province.Brill Archive. pp. 48–49.ISBN90-04-04384-5.

- ^Ricardo Padrón (1 February 2004).The Spacious Word: Cartography, Literature, and Empire in Early Modern Spain.University of Chicago Press. p.252.ISBN978-0-226-64433-2.

- ^Carl Waldman; Catherine Mason (2006).Encyclopedia of European Peoples.Infobase Publishing. p. 404.ISBN978-1-4381-2918-1.

- ^Strabo(1988).The Geography(in Greek and English). Vol. II. Horace Leonard Jones (trans.). Cambridge: Bill Thayer. p. 118, Note 1 on 3.4.19.

- ^Herodotus (1827).The nine books of the History of Herodotus, tr. from the text of T. Gaisford, with notes and a summary by P. E. Laurent.p. 75.

- ^abGeography III.4.19.

- ^III.37.

- ^III.17.

- ^Félix Gaffiot (1934).Dictionnaire illustré latin-français.Hachette. p. 764.

- ^Greg Woolf(8 June 2012).Rome: An Empire's Story.Oxford University Press. p. 18.ISBN978-0-19-997217-3.

- ^Berkshire Review.Williams College. 1965. p. 7.

- ^Carlos B. Vega (2 October 2003).Conquistadoras: Mujeres Heroicas de la Conquista de America.McFarland. p. 15.ISBN978-0-7864-8208-5.

- ^Virgil (1846).The Eclogues and Georgics of Virgil.Harper & Brothers. p.377.ISBN9789644236174.

- ^Vernet Pons 2014,p. 307.

- ^Vernet Pons 2014,p. 297.

- ^"La contribución de Bory de Saint-Vincent (1778–1846) al conocimiento geográfico de la Península Ibérica"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 25 September 2020.Retrieved5 April2020.

- ^III.3.21.

- ^White, Horace; Jona Lendering."Appian's History of Rome: The Spanish Wars (§§6–10)".livius.org. pp. Chapter 7. Archived fromthe originalon 20 December 2008.Retrieved1 December2008.

- ^"Polybius: The Histories: III.6.2".Bill Thayer.

- ^abMorris Student Plus,Basque-English dictionary

- ^Adams 2010,p. 208.

- ^Martí Oliver, Bernat (2012)."Redes y expansión del Neolítico en la Península Ibérica".Rubricatum. Revista del Museu de Gavà(in Spanish) (5). Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert: 549–553.ISSN1135-3791.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Olalde, Iñigo; et al. (15 March 2019)."The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years".Science.363(6432).American Association for the Advancement of Science:1230–1234.Bibcode:2019Sci...363.1230O.doi:10.1126/science.aav4040.PMC6436108.PMID30872528.

- ^Case, H (2007).'Beakers and Beaker Culture' Beyond Stonehenge: Essays on the Bronze Age in honour of Colin Burgess.Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 237–254.

- ^Ontañón Peredo, Roberto (2003).Caminos hacia la complejidad: el Calcolítico en la región cantábrica.Universidad de Cantabria.p. 72.ISBN9788481023466.

- ^García Rivero, Daniel; Escacena Carrasco, José Luis (July–December 2015)."Del Calcolítico al Bronce antiguo en el Guadalquivir inferior. El cerro de San Juan (Coria del Río, Sevilla) y el 'Modelo de Reemplazo'"(PDF).Zephyrus(in Spanish).76.Universidad de Salamanca:15–38.doi:10.14201/zephyrus2015761538.ISSN0514-7336.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Vázquez Hoys, Dra. Ana Mª (15 May 2005). Santos, José Luis (ed.)."Los Millares".Revista Terrae Antiqvae(in Spanish).UNED.Archived fromthe originalon 22 May 2022.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Lillios, Katina T. (2019). "The Emergence of Ranked Societies. The Late Copper Age To Early Bronze Age (2,500 – 1,500 BCE)".The Archaeology of the Iberian Peninsula. From the Paleolithic to the Bronze Age.Cambridge University Press.p. 227.doi:10.1017/9781316286340.007.S2CID240899082.

- ^Legarra Herrero, Borja (2021). "From systems of power to networks of knowledge: the nature of El Argar culture (southeastern Iberia, c. 2200–1500 BC)". In Foxhall, Lin (ed.).Interrogating Networks Investigating networks of knowledge in antiquity.Oxford:Oxbow Books.pp. 47–48.ISBN978-1-78925-627-7.

- ^Carrión et al. 2007,p. 1472.

- ^Chapman, R (2008). "Producing Inequalities: Regional Sequences in Later Prehistoric Southern Spain".Journal of World Prehistory.21(3–4): 209–210.doi:10.1007/s10963-008-9014-y.S2CID162289282.

- ^Chapman 2008,pp. 208–209.

- ^Legarra Herrero 2021,p. 52.

- ^Carrión, J.S.; Fuentes, N.; González-Sampériz, P.; Sánchez-Quirante, L.; Finlayson, J.C.; Fernández, S.; Andrade, A. (2007). "Holocene environmental change in a montane region of southern Europe with a long history of human settlement".Quaternary Science Reviews.26(11–12): 1472.Bibcode:2007QSRv...26.1455C.doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.03.013.

- ^Lugo Enrich, Luis Benítez de; Mejías, Miguel (2017). "The hydrogeological and paleoclimatic factors in the Bronze Age Motillas Culture of La Mancha (Spain): the first hydraulic culture in Europe".Hydrogeology Journal.25(7): 1933; 1946.Bibcode:2017HydJ...25.1931B.doi:10.1007/s10040-017-1607-z.hdl:20.500.12468/512.ISSN1435-0157.S2CID134088522.

- ^Valério, Miguel (2008)."Origin and development of the Paleohispanic scripts. the orthography and phonology of the Southwestern alphabet"(PDF).Revista portuguesa de arqueologia.11(2): 108–109.ISSN0874-2782.

- ^Cunliffe 1995,p. 15.

- ^Cunliffe 1995,p. 16.

- ^Ferrer i Jané, Joan (2017)."El origen dual de las escrituras paleohispánicas: un nuevo modelo genealógico"(PDF).Palaeohispanica.17:58.ISSN1578-5386.

- ^Rodá, Isabel (2013). "Hispania: From the Roman Republic to the Reign of Augustus". In Evans, Jane =DeRose (ed.).A companion to the archaeology of the Roman Republic.John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.p. 526.ISBN978-1-4051-9966-7.

- ^Rodá 2013,p. 526.

- ^Rodá 2013,p. 527.

- ^Rodá de Llanza, Isabel (2009)."Hispania en las provincias occidentales del imperio durante la república y el alto imperio: una pespectiva arqueológica"(PDF).Institut Català d'Arqueologia Clàssica. p. 197.

- ^Gosner, L. (2016). "Extraction and empire: multi-scalar approaches to Roman mining communities and industrial landscapes in southwest Iberia".Archaeological Review from Cambridge.31(2): 125–126.

- ^Padilla Peralta, Dan-el(2020). "Epistemicide: the Roman Case".Classica.33(2): 161–163.ISSN2176-6436.

- ^Curchin, Leonard A. (2014) [1991].Roman Spain. Conquest and Assimilation.Routledge.pp. 136–153.ISBN978-0-415-74031-9.

- ^Rodá 2013,p. 535.

- ^Rodá 2013,p. 533; 536.

- ^Zavagno-, Luca (2020).""No Island is an Island": The Byzantine Mediterranean in The Early Middle Ages (600s-850s) "(PDF).The Legends Avrupa Tarihi Çalışmaları Dergisi.1(1): 57–80.doi:10.29228/legends.44375.ISSN2718-0190.S2CID226576363.

- ^Cau Ontiveros, Miguel Ángel; Fantuzzi, Leandro; Tsantini, Evanthia; Mas Florit, Catalina; Chávez-Álvarez, Esther; Gandhi, Ajay (16 December 2020)."Archaeometric characterization of water jars from the Muslim period at the city of Pollentia (Alcúdia, Mallorca, Balearic Islands)".ArcheoSciences. Revue d'archéométrie(44): 7–17.doi:10.4000/archeosciences.7155.ISSN1960-1360.S2CID234569616.

- ^Abraham Ibn Daud's Dorot 'Olam (Generations of the Ages): A Critical Edition and Translation of Zikhron Divrey Romi, Divrey Malkhey Yisra?el, and the Midrash on Zechariah.BRILL. 7 June 2013. p. 57.ISBN978-90-04-24815-1.Retrieved10 August2013.

- ^Julio Samsó (1998).The Formation of Al-Andalus: History and society.Ashgate. pp. 41–42.ISBN978-0-86078-708-2.Retrieved10 August2013.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 41–42.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 43.

- ^Darío Fernández-Morera (9 February 2016).The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise.Intercollegiate Studies Institute. p. 286.ISBN978-1-5040-3469-2.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 47.

- ^F. E. Peters (11 April 2009).The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition, Volume I: The Peoples of God.Princeton University Press. p. 182.ISBN978-1-4008-2570-7.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 43–44.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 45.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 46.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 49.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 48.

- ^Marín-Guzmán 1991,p. 50.

- ^Flood 2019,p. 20.

- ^Constable 1994,p. 3.

- ^abVicens Vives 1970,p. 37.

- ^Safran 2000,p. 38–42.

- ^Ladero Quesada 2013,p. 167.

- ^Warfare in the Medieval World.Pen and Sword. 2006.ISBN9781848846326.

- ^Cavanaugh 2016,p. 4.

- ^Corbera, Laliena; Sénac, Philippe (12 August 2018)."La Reconquista, une entreprise géopolitique complexe".Atlantico.fr.

- ^García Fitz, Ayala Martínez & Alvira Cabrer 2018,p. 83–84.

- ^García Fitz, Ayala Martínez & Alvira Cabrer 2018,p. 84.

- ^Flood 2019,pp. 87–88.

- ^O'Callaghan 1983,p. 228.

- ^O'Callaghan 1983,p. 227.

- ^O'Callaghan 1983,p. 229.

- ^Buresi 2011,p. 5.

- ^Buresi 2011,pp. 2–3.

- ^Constable 1994,p. 2–3.

- ^abRodrigues 2011,p. 7.

- ^Ruiz 2021,pp. 88, 99.

- ^abWallerstein 2011,p. 49.

- ^Gillespie 2000,p. 1.

- ^Wallerstein 2011,p. 49–50.

- ^Fábregas García 2006,p. 1616.

- ^Fábregas García 2006,p. 16–17.

- ^Gillespie 2000,p. 4;Albarrán 2018,p. 37

- ^Muñoz Bolaños 2012,p. 154.

- ^abRuiz 2017,p. 18.

- ^Ruiz 2017,p. 19.

- ^Waugh, W. T. (14 April 2016).A History of Europe: From 1378 to 1494.Routledge.ISBN9781317217022– via Google Books.

- ^abPhillips 1996,p. 424.

- ^Berger, Julia Phillips; Gerson, Sue Parker (30 September 2006).Teaching Jewish History.Behrman House, Inc.ISBN9780867051834– via Google Books.

- ^Kantor, Máttis (30 September 2005).Codex Judaica: Chronological Index of Jewish History, Covering 5,764 Years of Biblical, Talmudic & Post-Talmudic History.Zichron Press.ISBN9780967037837– via Google Books.

- ^Aiken, Lisa (1 February 1997).Why Me God: A Jewish Guide for Coping and Suffering.Jason Aronson, Incorporated.ISBN9781461695479– via Google Books.

- ^Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (30 November 2004).Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities.Springer Science & Business Media.ISBN9780306483219– via Google Books.

- ^Gilbert 2003,p. 46;Schaff 2013

- ^Gerber 1994,p. 113.

- ^Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391–1392.Cambridge University Press. 2016. p. 19.ISBN9781107164512.

- ^Gloël 2017,p. 55.

- ^Escribano Páez 2016,pp. 189–191.

- ^Llorente 1843,p. 19.

- ^abGonzález Arévalo 2019,pp. 16–17.

- ^González Arévalo 2019,p. 16.

- ^Ladero Quesada 2013,p. 180.

- ^González Sánchez 2013,p. 350.

- ^abGonzález Sánchez 2013,p. 347.

- ^Religious Refugees in the Early Modern World: An Alternative History of the Reformation.Cambridge University Press. 2015. p. 108.ISBN9781107024564.

- ^The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia.Kingfisher. 2004. p.201.ISBN9780753457849.

- ^Beck, Bernard (30 September 2012).True Jew: Challenging the Stereotype.Algora Publishing.ISBN9780875869032– via Google Books.

- ^Strom, Yale (30 September 1992).The Expulsion of the Jews: Five Hundred Years of Exodus.SP Books. p.9.ISBN9781561710812– via Archive.org.

- ^NELSON, CARY R. (11 July 2016).Dreams Deferred: A Concise Guide to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and the Movement to Boycott Israel.Indiana University Press.ISBN9780253025180– via Google Books.

- ^"Islamic Encounters".www.brown.edu.Brown University.Retrieved25 May2023.

Between 1492 and 1610, some 3,000,000 Muslims voluntarily left or were expelled from Spain, resettling in North Africa.

- ^Gitlitz, David Martin (30 September 2002).Secrecy and Deceit: The Religion of the Crypto-Jews.UNM Press.ISBN9780826328137– via Google Books.

- ^The Jewish Time Line Encyclopedia: A Year-by-Year History From Creation to the Present.Jason Aronson, Incorporated. December 1993. p. 178.ISBN9781461631491.

- ^Latin America in Colonial Times.Cambridge University Press. 2018. p. 27.ISBN9781108416405.

- ^Pavlac, Brian A. (19 February 2015).A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History.Rowman & Littlefield.ISBN9781442237681– via Google Books.

- ^Jaleel, Talib (11 July 2015)."Notes on Entering Deen Completely: Islam as its followers know it".EDC Foundation – via Google Books.

- ^Majid, Anouar (30 September 2009).We are All Moors: Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities.U of Minnesota Press.ISBN9780816660797.

- ^"Special Initiative: Thucydides Trap".Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.3 September 1939.Retrieved12 January2024.

- ^el-Ojeili 2015,p. 4.

- ^Wallerstein 2011,p. 169–170.

- ^O'Brien & Prados de la Escosura 1998,p. 37–38.

- ^Wallerstein 2011,p. 116–117.

- ^Wallerstein 2011,p. 117.

- ^Liang et al. 2013,p. 23.

- ^Halikowski Smith, Stefan (2018)."Lisbon in the sixteenth century: decoding the Chafariz d'el Rei".Race & Class.60(2): 1–19.doi:10.1177/0306396818794355.S2CID220080922.

- ^Barrios 2015,p. 52.

- ^Nemser 2018,p. 117.

- ^Gelabert 1994,p. 183.

- ^abGelabert 1994,p. 183–184.

- ^Miranda 2017,p. 75–76.

- ^Miranda 2017,p. 76.

- ^O'Flanagan 2008,p. 18.

- ^abYun Casalilla 2019,p. 418.

- ^Yun Casalilla 2019,pp. 421, 423.

- ^Yun Casalilla 2019,p. 424.

- ^Yun Casalilla 2019,p. 425—426.

- ^Yun Casalilla 2019,p. 428—429.

- ^Silveira et al. 2013,p. 172.

- ^Sánchez Blanco 1988,pp. 21–32.

- ^III.1.3.

- ^Fischer, T (1920). "The Iberian Peninsula: Spain". In Mill, Hugh Robert (ed.).The International Geography.New York and London: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 368–377.

- ^These figures sum the figures given in the Wikipedia articles on the geography of Spain and Portugal. Most figures from Internet sources on Spain and Portugal include the coastlines of the islands owned by each country and thus are not a reliable guide to the coastline of the peninsula. Moreover, the length of a coastline may vary significantly depending on where and how it is measured.

- ^Edmunds, WM; K Hinsby; C Marlin; MT Condesso de Melo; M Manyano; R Vaikmae; Y Travi (2001). "Evolution of groundwater systems at the European coastline". In Edmunds, W. M.; Milne, C. J. (eds.).Palaeowaters in Coastal Europe: Evolution of Groundwater Since the Late Pleistocene.London: Geological Society. p. 305.ISBN1-86239-086-X.

- ^"Iberian Peninsula – Atlantic Coast".An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves(PDF).Global Ocean Associates. February 2004.Retrieved9 December2008.

- ^"Los 10 ríos mas largos de España".20 Minutos(in Spanish). 30 May 2013.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^"2. El territorio y la hidrografía española: ríos, cuencas y vertientes".Junta de Andalucía.Archived fromthe originalon 9 April 2022.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Manzano Cara, José Antonio."Tema 8.- El Relieve de España"(PDF)(in Spanish).Junta de Andalucía.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Piçarra, José Manuel; Gutiérrez-Marco, J. C.; Sá, Artur A.; Meireles, Carlos; González-Clavijo, E. (1 June 2006). "Silurian graptolite biostratigraphy of the Galicia – Tras-os-Montes Zone (Spain and Portugal)".GFF.128(2): 185.Bibcode:2006GFF...128..185P.doi:10.1080/11035890601282185.hdl:10261/30737.ISSN1103-5897.S2CID140712259.

- ^Edited by W Gibbons & T Moreno,Geology of Spain,2002,ISBN978-1-86239-110-9

- ^Jones, Peter."Introduction to the Birds of Spain".Spanishnature.com.Archived fromthe originalon 8 August 2020.Retrieved11 April2013.

- ^Rodrigues, Pedro M. S. M.; Antão, Ana Maria M. C.; Rodrigues, Ricardo (2019). "Evaluation of the impact of lithium exploitation at the C57 mine (Gonçalo, Portugal) on water, soil and air quality".Environmental Earth Sciences(78): 1.doi:10.1007/s12665-019-8541-4.

- ^Dahlkamp 1991,pp. 232–233.

- ^Tornos, F.; López Pamo, E.; Sánchez España, F.J. (2008)."The Iberian Pyrite Belt"(PDF).Contextos geológicos españoles: una aproximación al patrimonio geológico de relevancia internacional.Instituto Geológico y Minero de España.p. 57.

- ^Lorenzo-Lacruz et al. 2011,pp. 2582–2583.

- ^"IBERIAN CLIMATE ATLAS"(PDF).Aemet.es.Retrieved22 March2024.

- ^"Standard climate values for Córdoba".Aemet.es.Retrieved7 March2015.

- ^"Standard climate values for A Coruña".Aemet.es.Retrieved7 March2015.

- ^Sahlins 1989,p. 49.

- ^Paul Wilstach (1931).Along the Pyrenees.Robert M. McBride Company. p. 102.

- ^James Erskine Murray (1837).A Summer in the Pyrenees.J. Macrone. p.92.

- ^População residente (Série longa, início 1991 - N.º) por Local de residência (NUTS - 2013), Sexo e Idade; Anual 2022,"INE 2022"

- ^2023 Census data,"Official Spanish census"

- ^abSánchez Moral 2011,p. 312.

- ^Sánchez Moral 2011,p. 313.

- ^"Population on 1 January by broad age group, sex and metropolitan regions".Eurostat.

- ^Conservación Ex situ del Lince Ibérico: Un Enfoque Multidisciplinar(PDF).Fundación Biodiversidad. 2009. pp. XI & 527.

- ^Hortas, Francisco; Jordi Figuerols (2006)."Migration pattern of Curlew Sandpipers Calidris ferruginea on the south-western coastline of the Iberian Peninsula"(PDF).International Wader Studies.19:144–147. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 17 December 2008.Retrieved7 December2008.

- ^Dominguez, Jesus (1990)."Distribution of estuarine waders wintering in the Iberian Peninsula in 1978–1982"(PDF).Wader Study Group Bulletin.59:25–28.

- ^"El misterioso origen del euskera, el idioma más antiguo de Europa".Semana(in Spanish). 18 September 2017.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Fernández Jaén, Jorge."El latín en Hispania: la romanización de la Península Ibérica. El latín vulgar. Particularidades del latín hispánico".Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes(in Spanish).Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Echenique Elizondo, M.ª Teresa (March 2016)."Lengua española y lengua vasca: Una trayectoria histórica sin fronteras"(PDF).Revista de Filología(in Spanish) (34).Instituto Cervantes:235–252.ISSN0212-4130.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Andreose & Renzi 2013,pp. 289–290.

- ^abAndreose & Renzi 2013,p. 293.

- ^"El Gobierno Vasco ha presentado los resultados más destacados de la V. Encuesta Sociolingüística de la CAV, Navarra e Iparralde".Eusko Jaurlaritza(in Basque). 18 July 2012.Retrieved1 September2018.

- ^Andreose & Renzi 2013,pp. 290–291.

- ^Andreose & Renzi 2013,p. 291.

- ^ab"Gibraltar Fact Sheets".Government of Gibraltar.Retrieved4 November2022.

- ^Zafra, Ignacio (11 November 2019)."Spain continues to have one of the worst levels of English in Europe".El País.Retrieved4 November2022.

- ^Zembri & Libourel 2017,p. 368.

- ^Zembri & Libourel 2017,p. 371.

- ^Zembri & Libourel 2017,p. 382.

- ^Fernández de Alarcón 2015,p. 45.

- ^Barrenechea, Eduardo (10 January 1983)."El Canfranc: un ferrocarril en vía muerta".El País.

- ^Palmeiro Piñeiro & Pazos Otón 2008,p. 227.

- ^Fernández de Alarcón 2015,p. 50.

- ^García Álvarez 1996,p. 7; 11.

- ^Leadbeater, Chris (31 May 2018),"Will a Tunnel from Spain to Africa Ever Be Built—And Who Would Use It?",The Telegraph,archived fromthe originalon 19 December 2000.

- ^ab"Madrid΄s Position in the Global Telecommunications Landscape"(PDF).DE-CIX.p. 2. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 16 June 2020.Retrieved16 June2020.

- ^"Grace Hopper: el gran cable submarino de Google llega a España".Expansión.9 September 2021.