Icelandic language

| Icelandic | |

|---|---|

| íslenska | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈistlɛnska] |

| Native to | Iceland |

| Ethnicity | Icelanders |

Native speakers | (undated figure of 330,000)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Latin(Icelandic alphabet) Icelandic Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies[a] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | is |

| ISO 639-2 | ice(B)isl(T) |

| ISO 639-3 | isl |

| Glottolog | icel1247 |

| Linguasphere | 52-AAA-aa |

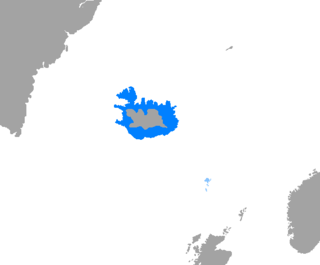

Geographic distribution of the Icelandic language | |

Icelandic(/aɪsˈlændɪk/eyess-LAN-dik;endonym:íslenska,pronounced[ˈistlɛnska]) is aNorth Germanic languagefrom theIndo-European language familyspoken by about 314,000 people, the vast majority of whom live inIceland,where it is the national language.[2]Since it is aWest Scandinavian language,it is most closely related toFaroese,westernNorwegian dialects,and theextinct languageNorn.It is not mutually intelligible with the continental Scandinavian languages (Danish,Norwegian,andSwedish) and is more distinct from the most widely spoken Germanic languages,EnglishandGerman.The written forms of Icelandic and Faroese are very similar, but their spoken forms are notmutually intelligible.[3]

The language is moreconservativethan most other Germanic languages. While most of them have greatly reduced levels ofinflection(particularly noundeclension), Icelandic retains a four-casesyntheticgrammar (comparable toGerman,though considerably more conservative and synthetic) and is distinguished by a wide assortment of irregular declensions. Icelandic vocabulary is also deeply conservative, with the country'slanguage regulatormaintaining an active policy of coining terms based on older Icelandic words rather than directly taking inloanwordsfrom other languages.

Aside from the 300,000 Icelandic speakers in Iceland, Icelandic is spoken by about 8,000 people in Denmark,[4]5,000 people in the United States,[5]and more than 1,400 people in Canada,[6]notably in the region known asNew IcelandinManitobawhich was settled by Icelanders beginning in the 1880s.

The state-fundedÁrni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studiesserves as a centre for preserving the medieval Icelandic manuscripts and studying the language and its literature. The Icelandic Language Council, comprising representatives of universities, the arts, journalists, teachers, and theMinistry of Culture, Science and Education,advises the authorities onlanguage policy.Since 1995, on 16 November each year, the birthday of 19th-century poetJónas Hallgrímssonis celebrated asIcelandic Language Day.[7]

Classification[edit]

Icelandic is anIndo-European languageand belongs to theNorth Germanicgroup of theGermanic languages.Icelandic is further classified as a West Scandinavian language.[8]Icelandic is derived from an earlier languageOld Norse,which later becameOld Icelandicand currently Modern Icelandic. The division between old and modern Icelandic is said to be before and after 1540.[9]

History[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2019) |

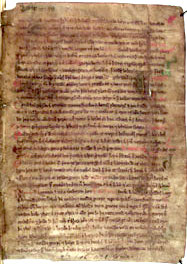

The oldest preserved texts in Icelandic were written around 1100 AD. Many of the texts are based on poetry and laws traditionally preserved orally. The most famous of the texts, which were written inIcelandfrom the 12th century onward, are thesagas of Icelanders,which encompass the historical works and thePoetic Edda.

The language of the sagas isOld Icelandic,a western dialect ofOld Norse.TheDano-Norwegian,then later Danish rule of Iceland from 1536 to 1918 had little effect on the evolution of Icelandic (in contrast to the Norwegian language), which remained in daily use among the general population. Though more archaic than the other living Germanic languages, Icelandic changed markedly in pronunciation from the 12th to the 16th century, especially in vowels (in particular,á,æ,au,andy/ý). The letters -ý & -y lost their original meaning and merged with -í & -i in the period 1400 - 1600. Around the same time or a little earlier the letter -æ originally signifying a simple vowel, a type of open -e, formed into the double vowel -ai, a double vowel absent in the original Icelandic.

The modernIcelandic alphabethas developed from a standard established in the 19th century, primarily by the Danish linguistRasmus Rask.It is based strongly on anorthographylaid out in the early 12th century by a document referred to as theFirst Grammatical Treatiseby an anonymous author, who has later been referred to as the First Grammarian. The later Rasmus Rask standard was a re-creation of the old treatise, with some changes to fit concurrentGermanicconventions, such as the exclusive use ofkrather thanc.Various archaic features, as the letterð,had not been used much in later centuries. Rask's standard constituted a major change in practice. Later 20th-century changes include the use oféinstead ofje[10]and the replacement ofzwithsin 1974.[11]

Apart from the addition of new vocabulary, written Icelandic has not changed substantially since the 11th century, when the first texts were written onvellum.[12]Modern speakers can understand the original sagas andEddaswhich were written about eight hundred years ago. The sagas are usually read with updated modern spelling and footnotes, but otherwise are intact (as with recent English editions ofShakespeare'sworks). With some effort, many Icelanders can also understand the original manuscripts.

Legal status and recognition[edit]

According to an act passed by theParliamentin 2011, Icelandic is "the national language of the Icelandic people and the official language in Iceland"; moreover, "[p]ublic authorities shall ensure that its use is possible in all areas of Icelandic society".[13]

Iceland is a member of theNordic Council,a forum for co-operation between the Nordic countries, but the council uses only Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish as its working languages (although the council does publish material in Icelandic).[14]Under theNordic Language Convention,since 1987 Icelandic citizens have had the right to use Icelandic when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries, without becoming liable for any interpretation or translation costs. The convention covers visits to hospitals, job centres, the police, and social security offices.[15][16]It does not have much effect since it is not very well known and because those Icelanders not proficient in the other Scandinavian languages often have a sufficient grasp of English to communicate with institutions in that language (although there is evidence that the general English skills of Icelanders have been somewhat overestimated).[17]The Nordic countries have committed to providing services in various languages to each other's citizens, but this does not amount to any absolute rights being granted, except as regards criminal and court matters.[18][19]

Phonology[edit]

Consonants[edit]

All Icelandicstopsare voiceless and are distinguished as such byaspiration.[20]Stops are realised post-aspirated when at the beginning of the word, but pre-aspirated when occurring within a word.[21][b]

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | (m̥) | m | (n̥) | n | (ɲ̊) | (ɲ) | (ŋ̊) | (ŋ) | ||

| Stop | pʰ | p | tʰ | t | (cʰ) | (c) | kʰ | k | ||

| Continuant | sibilant | s | ||||||||

| non-sibilant | f | v | θ | ð | (ç) | j | (x) | (ɣ) | h | |

| Lateral | (l̥) | l | ||||||||

| vibrant | (r̥) | r | ||||||||

- /n̥ntʰt/are laminaldenti-alveolar,/s/is apical alveolar,[22]/θð/are alveolar non-sibilant fricatives; the former islaminal,while the latter is usuallyapical.[23]

- A phonetic analysis reveals that the voiceless lateral approximant[l̥]is, in practice, usually realised with considerable friction, especially word-finally or syllable-finally, i. e., essentially as avoiceless alveolar lateral fricative[ɬ].[24]

Scholten (2000,p. 22) includes three extra phones:[ʔl̥ˠlˠ].

Word-final voiced consonants are devoiced pre-pausally, so thatdag('day (acc.)') is pronounced as[ˈtaːx]anddagur('day (nom.)') is pronounced[ˈtaːɣʏr̥].[25]

Vowels[edit]

Icelandic has 8 monophthongs and 5 diphthongs.[26]The diphthongs are created by taking a monophthong and adding either/i/or/u/to it.[27]All the vowels can either be long or short; vowels in open syllables are long, and vowels in closed syllables are short.[28]

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| plain | round | ||

| Close | i | u | |

| Near-close | ɪ | ʏ | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | œ | ɔ |

| Open | a | ||

| Front offglide |

Back offglide | |

|---|---|---|

| Mid | ei•œi[œy][c] | ou |

| Open | ai | au |

Grammar[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2019) |

Icelandic retains many grammatical features of other ancientGermanic languages,and resemblesOld Norwegianbefore much of itsfusionalinflection was lost. Modern Icelandic is still a heavilyinflected languagewith fourcases:nominative,accusative,dativeandgenitive.Icelandic nouns can have one of threegrammatical genders:masculine, feminine or neuter. There are two main declension paradigms for each gender:strongandweak nouns,and these are further divided into subclasses of nouns, based primarily on thegenitive singularandnominative pluralendings of a particular noun. For example, within the strong masculine nouns, there is a subclass (class 1) that declines with-s(hests) in the genitive singular and-ar(hestar) in the nominative plural. However, there is another subclass (class 3) of strong masculine nouns that always declines with-ar(hlutar) in the genitive singular and-ir(hlutir) in the nominative plural. Additionally, Icelandic permits aquirky subject,that is, certain verbs have subjects in an oblique case (i.e. other than the nominative).

Nouns, adjectives and pronouns are declined in the four cases and for number in the singular and plural.

Verbsareconjugatedfortense,mood,person,numberandvoice.There are three voices: active, passive and middle (or medial), but it may be debated whether the middle voice is a voice or simply an independent class of verbs of its own, as every middle-voice verb has an active-voice ancestor, but sometimes with drastically different meaning, and the middle-voice verbs form a conjugation group of their own. Examples arekoma( "come" ) vs.komast( "get there" ),drepa( "kill" ) vs.drepast( "perish ignominiously" ) andtaka( "take" ) vs.takast( "manage to" ). In each of these examples, the meaning has been so altered, that one can hardly see them as the same verb in different voices. Verbs have up to ten tenses, but Icelandic, like English, forms most of them withauxiliary verbs.There are three or four main groups of weak verbs in Icelandic, depending on whether one takes a historical or a formalistic view:-a,-i,and-ur,referring to the endings that these verbs take when conjugated in the first personsingularpresent. Almost all Icelandic verbs have the ending -a in the infinitive, some withá,two withu(munu,skulu) one witho(þvo:"wash" ) and one withe.Many transitive verbs (i.e. they require anobject), can take areflexive pronouninstead. The case of the pronoun depends on the case that the verb governs. As for further classification of verbs, Icelandic behaves much like other Germanic languages, with a main division between weak verbs and strong, and the strong verbs, of which there are about 150 to 200, are divided into six classes plus reduplicative verbs.

The basic word order in Icelandic issubject–verb–object.However, as words are heavily inflected, the word order is fairly flexible, and every combination may occur in poetry; SVO, SOV, VSO, VOS, OSV and OVS are all allowed for metrical purposes. However, as with most Germanic languages, Icelandic usually complies with theV2 word orderrestriction, so the conjugated verb in Icelandic usually appears as the second element in the clause, preceded by the word or phrase being emphasised. For example:

- Ég veit það ekki.(Iknow it not.)

- Ekki veit ég það.(Notknow I it.)

- Það veit ég ekki.(Itknow I not.)

- Ég fór til Bretlands þegar ég var eins árs.(I went to Britain when I was one year old.)

- Til Bretlands fór ég þegar ég var eins árs.(To Britain went I, when I was one year old.)

- Þegar ég var eins árs fór ég til Bretlands.(When I was one year old, went I to Britain.)

In the above examples, the conjugated verbsveitandfórare always the second element in their respective clauses, seeverb-second word order.

A distinction between formal and informal address (T–V distinction) had existed in Icelandic from the 17th century, but use of the formal variant weakened in the 1950s and rapidly disappeared.[30]It no longer exists in regular speech, but may occasionally be found in pre-written speeches addressed to thebishopand members ofparliament.[30]

Vocabulary[edit]

Early Icelandic vocabulary was largelyOld Norsewith a few words being Celtic from when Celts first settled in Iceland.[31][32]Theintroduction of Christianity to Icelandin the 11th century[33]brought with it a need to describe newreligious concepts.The majority of new words were taken from otherScandinavian languages;kirkja( "church" ), for example. Numerous other languages have influenced Icelandic:Frenchbrought many words related to the court and knightship; words in thesemantic fieldof trade and commerce have been borrowed fromLow Germanbecause of trade connections. In the late 18th century,language purismbegan to gain noticeable ground in Iceland and since the early 19th century it has been the linguistic policy of the country (seelinguistic purism in Icelandic).[34]Nowadays, it is common practice tocoinnew compound words from Icelandic derivatives.

Icelandic personal namesarepatronymic(and sometimesmatronymic) in that they reflect the immediate father or mother of the child and not the historic family lineage. This system, which was formerly used throughout the Nordic area and beyond, differs from mostWesternsystems offamily name.In most Icelandic families, the ancient tradition of patronymics is still in use; i.e. a person uses their father's name (usually) or mother's name (increasingly in recent years) in the genitive form followed by the morpheme -son ( "son" ) or -dóttir ( "daughter" ) in lieu of family names.[35]

In 2019, changes were announced to the laws governing names. Icelanders who are officially registered withnon-binary genderwill be permitted to use the suffix-bur( "child of" ) instead of-sonor-dóttir.[36]

Language policy[edit]

A core theme of Icelandic language ideologies is grammatical, orthographic and lexical purism for Icelandic. This is evident in general language discourses, in polls, and in other investigations into Icelandic language attitudes.[37]The general consensus on Icelandic language policy has come to mean that language policy and language ideology discourse are not predominantly state or elite driven; but rather, remain the concern of lay people and the general public.[38]The Icelandic speech community is perceived to have a protectionist language culture,[35]however, this is deep-rooted ideologically primarily in relation to the forms of the language, while Icelanders in general seem to be more pragmatic as to domains of language use.[39]

Linguistic purism[edit]

Starting in the late 16th century discussion has been ongoing on the purity of the Icelandic language, the bishop Oddur Einarsson wrote in 1589 that the language has remained unspoiled since the time the ancient literature of Iceland was written.[40]Later in the 18th century the purism movement got bigger and more works were translated into Icelandic, especially in areas where Icelandic had hardly ever been used in, with this came manyneologisms,with many of them being loan-translations.[40]In the early 19th century people were influenced byromanticismand a bigger importance was put on the purity of spoken language, instead of just the written language. The written language was also brought closer to the spoken language as the sentence structure of literature had previously been influenced byDanishandGerman.[41]

The changes brought by the purism movement have had the most influence on the written language, as many speakers use foreign words freely in speech, but try to avoid them when writing. The success of the many neologisms created from the movement has also been variable as some loanwords have not been replaced with native ones.[42]There is still a conscious effort to create new words, especially for science and technology, with many societies publishing dictionaries, some with the help of The Icelandic Language Committee (Íslensk málnefnd).[43]

Writing system[edit]

The Icelandic alphabet is notable for its retention of three old letters that no longer exist in theEnglish alphabet:Þ, þ(þorn,modern English "thorn" ),Ð, ð(eð,anglicised as "eth" or "edh" ) andÆ, æ(æsc, anglicised as "ash" or "asc" ), with þ and ð representing thevoicelessandvoiced"th" sounds (as in Englishthinandthis), respectively, and æ representing thediphthong/ai/ which does not exist in English. The complete Icelandic alphabet is:

| Majuscule forms(also calleduppercaseorcapital letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Á | B | D | Ð | E | É | F | G | H | I | Í | J | K | L | M | N | O | Ó | P | R | S | T | U | Ú | V | X | Y | Ý | Þ | Æ | Ö |

| Minuscule forms(also calledlowercaseorsmall letters) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | á | b | d | ð | e | é | f | g | h | i | í | j | k | l | m | n | o | ó | p | r | s | t | u | ú | v | x | y | ý | þ | æ | ö |

Theletters with diacritics,such asáandö,are for the most part treated as separate letters and not variants of their derivative vowels. The letteréofficially replacedjein 1929, although it had been used in early manuscripts (until the 14th century) and again periodically from the 18th century.[10]The letterzwas formerly in the Icelandic alphabet, but it was officially removed in 1974, except in people's names.[11][44]

See also[edit]

- Basque–Icelandic pidgin(apidginthat was used to trade withBasquewhalers)

- Icelandic exonyms

- Icelandic literature

- Icelandic name

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^IcelandicatEthnologue(26th ed., 2023)

- ^Icelandic languageatEthnologue(19th ed., 2016)

- ^Barbour & Carmichael 2000,p. 106.

- ^"StatBank Denmark".www.statbank.dk.

- ^"Icelandic".MLA Language Map Data Center.Modern Language Association.Archived fromthe originalon 6 December 2010.Retrieved17 April2010.Based on2000 US census data.

- ^Government of Canada (8 May 2013)."2011 National Household Survey: Data tables".Statistics Canada.

- ^"Icelandic: At Once Ancient And Modern"(PDF).Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture.2001. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 26 August 2019.Retrieved27 April2007.

- ^Karlsson 2013,p. 8.

- ^Thráinsson 1994,p. 142.

- ^abKvaran, Guðrún (12 November 2001)."Hvenær var bókstafurinn 'é' tekinn upp í íslensku í stað 'je' og af hverju er 'je' enn notað í ýmsum orðum?".Vísindavefurinn(in Icelandic).Retrieved20 June2007.

- ^abKvaran, Guðrún (7 March 2000)."Hvers vegna var bókstafurinn z svona mikið notaður á Íslandi en því svo hætt?".Vísindavefurinn(in Icelandic).Archivedfrom the original on 29 October 2023.Retrieved29 October2023.

- ^Sanders, Ruth (2010).German: Biography of a Language.Oxford University Press. p. 209.

Overall, written Icelandic has changed little since the eleventh century Icelandic sagas, or historical epics; only the addition of significant numbers of vocabulary items in modern times makes it likely that a saga author would have difficulty understanding the news in today's [Icelandic newspapers].

- ^"Act [No 61/2011] on the status of the Icelandic language and Icelandic sign language"(PDF).Ministry of Education, Science and Culture.p. 1.Retrieved15 November2013.

Article 1; National language – official language; Icelandic is the national language of the Icelandic people and the official language in Iceland. Article 2; The Icelandic language — The national language is the common language of the Icelandic general public. Public authorities shall ensure that its use is possible in all areas of Icelandic society. All persons residing in Iceland must be given the opportunity to learn Icelandic and to use it for their general participation in Icelandic society, as further provided in leges speciales.

- ^"Norden".Retrieved27 April2007.

- ^"Nordic Language Convention".Archived fromthe originalon 29 June 2007.Retrieved27 April2007.

- ^"Nordic Language Convention".Archived fromthe originalon 28 April 2009.Retrieved27 April2007.

- ^Robert Berman."The English Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency of Icelandic students, and how to improve it".Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.

English is often described as being almost a second language in Iceland, as opposed to a foreign language like German or Chinese. Certainly in terms of Icelandic students' Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS), English does indeed seem to be a second language. However, in terms of many Icelandic students' Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP)—the language skills required for success in school—evidence will be presented suggesting that there may be a large number of students who have substantial trouble utilizing these skills.

- ^Language Convention not working properlyArchived2009-04-28 at theWayback Machine,Nordic news,March 3, 2007. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.

- ^Helge Niska,"Community interpreting in Sweden: A short presentation",International Federation of Translators,2004. Retrieved on April 25, 2007.Archived2009-03-27 at theWayback Machine

- ^Árnason 2011,p. 99.

- ^abFlego & Berkson 2020,p. 1.

- ^Kress 1982,pp. 23-24: "It's never voiced, assinsausen,and it's pronounced by pressing the tip of the tongue against the alveolar ridge, close to the upper teeth – somewhat below the place of articulation of the Germansch.The difference is that Germanschis labialized, while Icelandicsis not. It's a pre-alveolar, coronal, voiceless spirant. ".

- ^Ladefoged & Maddieson 1996,pp. 144–145.

- ^Liberman, Mark."A little Icelandic phonetics".Language Log.University of Pennsylvania.Retrieved1 April2012.

- ^Árnason 2011,pp. 107, 237.

- ^Flego & Berkson 2020,p. 8.

- ^Árnason 2011,p. 57.

- ^Árnason 2011,pp. 58–59.

- ^Árnason 2011,p. 58.

- ^ab"Þéranir á meðal vor".Morgunblaðið.29 October 1999.

- ^Brown & Ogilvie 2010,p. 781.

- ^Karlsson 2013,p. 9.

- ^Forbes 1860.

- ^Van der Hulst 2008.

- ^abHilmarsson-Dunn & Kristinsson 2010.

- ^Kyzer, Larissa (22 June 2019)."Icelandic names will no longer be gendered".Iceland Review.

- ^Kristinsson 2018.

- ^Kristinsson 2013.

- ^Kristinsson 2014.

- ^abKarlsson 2013,p. 36.

- ^Karlsson 2013,pp. 37–38.

- ^Karlsson 2013,p. 38.

- ^Thráinsson 1994,p. 188.

- ^Ragnarsson 1992,p. 148.

Bibliography[edit]

- Árnason, Kristján; Sigrún Helgadóttir (1991). "Terminology and Icelandic Language Policy".Behovet och nyttan av terminologiskt arbete på 90-talet. Nordterm 5. Nordterm-symposium.pp. 7–21.

- Árnason, Kristján (2011),The Phonology of Icelandic and Faroese,Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0-19-922931-4

- Barbour, Stephen; Carmichael, Cathie (2000).Language and Nationalism in Europe.OUP Oxford.ISBN978-0-19-158407-7.

- Brown, Edward Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (2010).Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world.Elsevier.ISBN9780080877754.OCLC944400471.

- Forbes, Charles Stuart (1860).Iceland: Its Volcanoes, Geysers, And Glaciers.Creative Media Partners, LLC. p. 61.ISBN978-1298551429.

- Halldórsson, Halldór (1979). "Icelandic Purism and its History".Word.30:76–86.

- Hilmarsson-Dunn, Amanda; Kristinsson, Ari Páll (2010)."The language situation in Iceland".Current Issues in Language Planning.11(3): 207–276.doi:10.1080/14664208.2010.538008.ISSN1466-4208.S2CID144856348.

- Karlsson, Stefán (2013) [2004].The Icelandic language.Translated by McTurk, Rory (Reprinted with minor corrections ed.). London: Viking Society for Northern Research, University College London.ISBN978-0-903521-61-1.

- Kress, Bruno (1982),Isländische Grammatik,VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie Leipzig

- Kristinsson, Ari Páll (1 November 2013)."Evolving language ideologies and media practices in Iceland / Die Entwicklung neuer Sprachideologien und Medienpraktiken in Island / Evolution des ideologies linguistiques et des pratiques médiatiques en Islande".Sociolinguistica(in German).27(1): 54–68.doi:10.1515/soci.2013.27.1.54.ISSN1865-939X.S2CID142164040.

- Kristinsson, Ari Páll (24 October 2014)."Ideologies in Iceland: The protection of language forms".In Hultgren, Anna Kristina; Gregersen, Frans; Thøgersen, Jacob (eds.).English in Nordic Universities.Studies in World Language Problems. Vol. 5. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 165–177.doi:10.1075/wlp.5.08kri.ISBN978-90-272-2836-9.

- Kristinsson, Ari Páll (2018)."National language policy and planning in Iceland – aims and institutional activities"(PDF).Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Research Institute for Linguistics.Budapest: 243–249.ISBN978-963-9074-74-3.

- Kvaran, Guðrún; Höskuldur Þráinsson; Kristján Árnason; et al. (2005).Íslensk tunga I–III.Reykjavík: Almenna bókafélagið.ISBN9979-2-1900-9.OCLC71365446.

- Ladefoged, Peter;Maddieson, Ian(1996).The Sounds of the World's Languages.Oxford: Blackwell.ISBN0-631-19815-6.

- Orešnik, Janez;Magnús Pétursson (1977). "Quantity in Modern Icelandic".Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi.92:155–71.

Ragnarsson, Baldur (1992).Mál og málsaga[Language and language history] (in Icelandic). Mál og Menning.ISBN978-9979-3-0417-3.

- Rögnvaldsson, Eiríkur (1993).Íslensk hljóðkerfisfræði[Icelandic phonology]. Reykjavík: Málvísindastofnun Háskóla Íslands.ISBN9979-853-14-X.

- Scholten, Daniel (2000).Einführung in die isländische Grammatik.Munich: Philyra Verlag.ISBN3-935267-00-2.OCLC76178278.

- Flego, Stefon; Berkson, Kelly (8 July 2020)."A Phonetic Illustration of the Sound System of Icelandic".ResearchGate.

- Thráinsson, Höskuldur (1994). "Icelandic". In König, Ekkehard; Van der Auwera, Johan (eds.).The Germanic languages.Routledge language family descriptions. London: Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-05768-4.

- Van der Hulst, Harry (2008).Word Prosodic Systems in the Languages of Europe.Mouton de Gruyter. p. 377.ISBN978-1282193666.OCLC741344348.

- Vikør, Lars S. (1993).The Nordic Languages. Their Status and Interrelations.Oslo: Novus Press. pp. 55–59, 168–169, 209–214.

External links[edit]

- The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies

- Íðorðabankinn,dictionary for technical words.

- Collection of Icelandic bilingual dictionaries