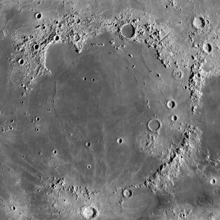

Mare Imbrium

A map showing the location of Mare Imbrium | |

| Coordinates | 32°48′N15°36′W/ 32.8°N 15.6°W |

|---|---|

| Diameter | 1,146 km (712 mi)[1] |

| Eponym | Sea of Showers or Sea of Rains |

Mare Imbrium/ˈɪmbriəm/(Latinimbrium,the "Sea of Showers"or"Sea of Rains") is a vastlava plainwithin the Imbrium Basin on theMoonand is one of thelarger craters in the Solar System.The Imbrium Basin formed from the collision of aproto-planetduring theLate Heavy Bombardment.Basalticlavalater flooded the giantcraterto form the flat volcanic plain seen today. The basin's age has been estimated usinguranium–lead dating methodsto approximately 3.9 billion years ago, and the diameter of the impactor has been estimated to be 250 ± 25 km.[2]The Moon's maria (plural ofmare) have fewer features than other areas of the Moon because molten lava pooled in the craters and formed a relatively smooth surface. Mare Imbrium is not as flat as it would have originally been when it first formed as a result of later events that have altered its surface.

Origin[edit]

Mare Imbrium formed when a proto-planet from the asteroid belt collided with the Moon during theLate Heavy Bombardment.[3]The impact is dated to approximately 3922 ± 12 million years ago, based onradiometric datingtechniques.Ejectafrom the impact covers large areas of the near side of the Moon.[4][5]

Characteristics[edit]

With a diameter of 1145 km, Mare Imbrium is second only toOceanus Procellarumin size among the maria, and it is the largest mare associated with an impact basin.

The Imbrium Basin is surrounded by three concentric rings of mountains, uplifted by the colossal impact event that excavated it. The outermost ring of mountains has a diameter of 1300 km and is divided into several different ranges; theMontes Carpatusto the south, theMontes Apenninusto the southeast, and theMontes Caucasusto the east. The ring mountains are not as well developed to the north and west, and it appears they were simply not raised as high in these regions by the Imbrium impact. The middle ring of mountains forms theMontes Alpesand the mountainous regions near thecratersArchimedesandPlato.The innermost ring, with a diameter of 600 km, has been largely buried under the mare's basalt leaving only low hills protruding through the mare plains and mare ridges forming a roughly circular pattern.

The outer ring of mountains rise roughly 7 km above the surface of Mare Imbrium. The Mare material is thought to be about 5 km deep, giving the Imbrium Basin a total depth of 12 km; it is thought that the original crater left by the Imbrium impact was as much as 100 km deep, but that the floor of the basin bounced back upwards immediately afterwards.

Surrounding the Imbrium Basin is a region blanketed byejectafrom the impact, extending roughly 800 km outward. Also encircling the basin is a pattern of radial grooves called the "Imbrium Sculpture", which have been interpreted as furrows cut in the Moon's surface by large projectiles blasted out of the basin at low angles, causing them to skim across the lunar surface ploughing out these features. The sculpture pattern was first identified byGrove Karl Gilbertin 1893.[6]Furthermore, a Moon-wide pattern of faults which run both radial to and concentric to the Imbrium basin were thought to have been formed by the Imbrium impact; the event literally shattered the Moon's entirelithosphere.At the region of the Moon's surface exactly opposite Imbrium Basin, there is a region of chaotic terrain (the craterVan de Graaff) which is thought to have been formed when the seismic waves of the impact were focused there after travelling through the Moon's interior. Mare Imbrium is about 750 miles (1,210 km) wide.

Amass concentration(mascon), or gravitational high, was identified in the center of Mare Imbrium from Doppler tracking of the fiveLunar Orbiterspacecraft in 1968.[7]The Imbrium mascon is the largest on the Moon. It was confirmed and mapped at higher resolution with later orbiters such asLunar ProspectorandGRAIL.

-

Shaded Relief map

-

Gravity map based onGRAIL

Names[edit]

Like most of the other maria on the Moon, Mare Imbrium was named byGiovanni Riccioli,whose 1651 nomenclature system has become standardized.[8]

The earliest known name for the mare may be "The Shrine ofHecate";Plutarchrecords that theAncient Greeksgave this name to the largest of the "hollows and deeps" on the Moon, believing it to be the place where the souls of the deceased were tormented. Ewen A. Whitaker argues that this likely refers to Mare Imbrium, "the largest regular-shaped dark area unbroken by bright patches" that can be seen with the naked eye.[9]

Around 1600,William Gilbertmade a map of the Moon that names Mare Imbrium "Regio Magna Orientalis" (the Large Eastern Region).Michael van Langren's 1645 map named it "Mare Austriacum" (the Austrian Sea).[10]

Observation and exploration[edit]

Mare Imbrium is visible to thenaked eyefrom Earth. In the traditional 'Man in the Moon' image seen on the Moon in Western folklore, Mare Imbrium forms the man's right eye.[11]

Luna 17[edit]

On 17 November 1970 at 03:47 Universal Time, the Soviet spacecraftLuna 17made a soft landing in the mare, at latitude 38.28 N, and longitude 35.00 W. Luna 17 carriedLunokhod 1,the first roboticroverto be deployed on the Moon or any extraterrestrial body. Lunokhod 1, a remote-controlled rover, was successfully deployed and undertook a mission lasting several months.

Apollo 15[edit]

In 1971, the crewedApollo 15mission landed in the southeastern region of Mare Imbrium, betweenHadley Rilleand theApennine Mountains.CommanderDavid Scottand Lunar Module PilotJames Irwinspent three days on the surface of the Moon, including 18½ hours outside the spacecraft on lunarextra-vehicular activity.Command Module PilotAlfred Wordenremained in orbit and acquired hundreds of high-resolution photographs of Mare Imbrium (and other regions of the Moon) as well as other types of scientific data. The crew on the surface explored the area using the firstlunar roverandreturned to Earthwith 77 kilograms (170 lb) of lunar surface material. Samples were collected fromMons Hadley Delta,believed to be a fault block of pre-Imbrian (NectarianorPre-Nectarian) lunar crust, including the "Genesis Rock."This was also the only Apollo mission to visit a lunar rille, and to observe outcrops of lunar bedrock visible in the rille wall.[12]

2013 Impact[edit]

On 17 March 2013, an object hit the lunar surface in Mare Imbrium and exploded in a flash ofapparent magnitude4.[13]The resulting crater was 18 meters wide.[14]This was the brightest impact recorded since NASA's lunar impact team began monitoring in 2005.

Chinese landing[edit]

Chang'e 3 landed on 14 December 2013 on Mare Imbrium, about 40 km south of the 6 km diameterLaplace Fcrater,[15][16]at 44.1260°N 19.5014°W.[16][17][18] The lander deployed the Yutu rover 7 hours and 24 minutes later.[19]Chang'e 3 mission attempted to perform the first direct measurement of the structure and depth of thelunar soildown to a depth of 30 m (98 ft), and investigate thelunar crust structuredown to several hundred meters deep.[20]The rover's ground penetrating radar found evidence of at least nine distinctrock layers,indicating that the area had surprisingly complex geological processes and is compositionally distinct from the Apollo and Luna landing sites.[21][22]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"Mare Imbrium".Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature.USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^P. H. Schultz & D.A. Crawford,Origin and implications of non-radial Imbrium Sculpture on the Moon,Nature535,391–394 (2016)

- ^Merle, R. E.; Nemchin, A. A.; Grange, M. L.; Whitehouse, M. J.; Pidgeon, R. T. (2014)."High resolution U-Pb ages of Ca-phosphates in Apollo 14 breccias: Implications for the age of the Imbrium impact".Meteoritics & Planetary Science.49(12): 2241–2251.Bibcode:2014M&PS...49.2241M.doi:10.1111/maps.12395.

- ^Nemchin, Alexander A.; Long, Tao; Jolliff, Bradley L.; Wan, Yusheng; Snape, Joshua F.; Zeigler, Ryan; Grange, Marion L.; Liu, Dunyi; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Timms, Nicholas E.; Jourdan, Fred (1 April 2021)."Ages of lunar impact breccias: Limits for timing of the Imbrium impact".Geochemistry.81(1): 125683.Bibcode:2021ChEG...81l5683N.doi:10.1016/j.chemer.2020.125683.hdl:20.500.11937/90165.ISSN0009-2819.S2CID224884243.

- ^Zhang, Bidong; Lin, Yangting; Moser, Desmond E.; Hao, Jialong; Shieh, Sean R.; Bouvier, Audrey (December 2019)."Imbrium Age for Zircons in Apollo 17 South Massif Impact Melt Breccia 73155".Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.124(12): 3205–3218.Bibcode:2019JGRE..124.3205Z.doi:10.1029/2019JE005992.ISSN2169-9097.S2CID210277861.

- ^Gilbert, Grove Karl.The Moon's face, a study of the origin of its features.Washington, Philosophical Society of Washington, 1893.

- ^P. M. Muller, W. L. Sjogren (1968). "Mascons: Lunar Mass Concentrations".Science.161(3842): 680–684.Bibcode:1968Sci...161..680M.doi:10.1126/science.161.3842.680.PMID17801458.S2CID40110502.

- ^Ewen A. Whitaker,Mapping and Naming the Moon(Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 61.

- ^Ewen A. Whitaker,Mapping and Naming the Moon(Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 7

- ^Ewen A. Whitaker,Mapping and Naming the Moon(Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 15, 41.

- ^Ewen A. Whitaker,Mapping and Naming the Moon(Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 3.[ISBN missing]

- ^Apollo 15 Preliminary Science Report(NASA SP-289), Scientific and Technical Information Office, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C., 1972.

- ^Dr. Tony Phillips (17 May 2013)."Bright Explosion on the Moon".Science@NASA.Retrieved19 May2013.

- ^NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center (17 March 2015)."New Craters on the Moon".Goddard Media Studios.Retrieved13 May2022.

- ^"Chang'e 3 landing coordinates".China News (CN).14 December 2013.Retrieved15 December2013.

- ^abEmily Lakdawalla; Phil Stooke (December 2013)."Chang'e 3 has successfully landed on the Moon!".The Planetary Society.Retrieved15 December2013.

- ^"China successfully lands robotic rover on the moon>".

- ^"Landing map of Chang'e 3".

- ^O'Neil, Ian (14 December 2013)."China's Rover Rolls! Yutu Begins Moon Mission".Discovery News.CCTV. Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2016.Retrieved15 December2013.

- ^"Âu dương tự viễn: Thường nga tam hào minh niên phát xạ tương thật hiện trứ lục khí dữ nguyệt cầu xa liên hợp tham trắc".Xinhua. 14 June 2012. Archived fromthe originalon 17 June 2012.Retrieved23 July2013.

- ^Wall, Mike (12 March 2015)."The Moon's History Is Surprisingly Complex, Chinese Rover Finds".Space.com.Retrieved13 March2015.

- ^Xiao, Long (13 March 2015). "A young multilayered terrane of the northern Mare Imbrium revealed by Chang'E-3 mission".Science.347(6227): 1226–1229.Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1226X.doi:10.1126/science.1259866.PMID25766228.S2CID206561783.

External links[edit]

- Phillips, Tony (13 June 2006)."A Meteoroid Hits the Moon".Science@NASA. Archived fromthe originalon 16 June 2006.Retrieved16 June2006.

- Mare Imbrium at The Moon Wiki

- Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (28 December 2000)."Moon Mare and Montes".Astronomy Picture of the Day.NASA.– one of the prominent features of the photo includes Mare Imbrium