Imperial Japanese Navy

| Imperial Japanese Navy | |

|---|---|

| Đại nhật bổn đế quốc hải quân (Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kaigun) | |

| |

| Founded | 1868 |

| Disbanded | 1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Naval warfare |

| Part of | |

| Colors | Navy Blue and White |

| March | "Gunkan kōshinkyoku"(" Gunkan March ") |

| Anniversaries | 27 May |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-chief | Emperor of Japan |

| Minister of the Navy | See list |

| Chief of the Navy General Staff | See list |

| Insignia | |

| Roundel |  |

| Ranks | Ranks of the Imperial Japanese Navy |

| Aircraft flown | |

| List of aircraft | |

TheImperial Japanese Navy(IJN;Kyūjitai:Đại nhật bổn đế quốc hải quânShinjitai:Đại nhật bổn đế quốc hải quân'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', orNhật bổn hải quânNippon Kaigun,'Japanese Navy') was thenavyof theEmpire of Japanfrom 1868 to 1945,when it was dissolvedfollowingJapan's surrender in World War II.TheJapan Maritime Self-Defense Force(JMSDF) was formed between 1952 and 1954 after the dissolution of the IJN.[1]

The Imperial Japanese Navy was the third largest navy in the world by 1920, behind theRoyal Navyand theUnited States Navy(USN).[2]It was supported by theImperial Japanese Navy Air Servicefor aircraft and airstrike operation from the fleet. It was the primary opponent of theWestern Alliesin thePacific War.

The origins of the Imperial Japanese Navy go back to early interactions with nations on theAsian continent,beginning in the earlyfeudal periodand reaching a peak of activity during the 16th and 17th centuries at a time ofcultural exchangewithEuropeanpowersduring theAge of Discovery.After two centuries of stagnation during the country's ensuingseclusion policyunder theshōgunof theEdo period,Japan's navy was comparatively backward when the country was forced open to trade byAmerican interventionin 1854. This eventually led to theMeiji Restoration.Accompanying the re-ascendance of theEmperorcame a period of franticmodernizationandindustrialization.The navy had several successes, sometimes against much more powerful enemies such as in theSino-Japanese Warand theRusso-Japanese War,before being largely destroyed in World War II.

Origins

[edit]

Japan has a long history of naval interaction with the Asian continent, involving transportation of troops betweenKoreaand Japan, starting at least with the beginning of theKofun periodin the 3rd century.[3]

Following the attempts atMongol invasions of JapanbyKubilai Khanin 1274 and 1281, Japanesewakōbecame very active inplunderingthe coast ofChina.[4][5]In response to threats of Chinese invasion of Japan, in 1405 the shogunAshikaga Yoshimitsucapitulated to Chinese demands and sent twenty captured Japanese pirates to China, where they were boiled in a cauldron inNingbo.[6]

Japan undertook major naval building efforts in the 16th century, during theWarring States periodwhen feudal rulers vying for supremacy built vast coastal navies of several hundred ships. Around that time Japan may have developed one of the firstironcladwarships whenOda Nobunaga,adaimyō,had six iron-coveredOatakebunemade in 1576.[7]In 1588Toyotomi Hideyoshiissued a ban on Wakō piracy; the pirates then became vassals of Hideyoshi, and comprised the naval force used in theJapanese invasion of Korea (1592–1598).[5]

Japan built her first large ocean-going warships in the beginning of the 17th century, following contacts with the Western nations during theNanban trade period.In 1613, thedaimyōofSendai,in agreement with theTokugawaBakufu,builtDate Maru,a 500-tongalleon-type ship that transported the Japanese embassy ofHasekura Tsunenagato the Americas, which then continued to Europe.[8]From 1604 the Bakufu also commissioned about 350Red seal ships,usually armed and incorporating some Western technologies, mainly forSoutheast Asiantrade.[9][10]

Western studies and the end of seclusion

[edit]

For more than 200 years, beginning in the 1640s, the Japanese policy of seclusion ( "sakoku") forbade contacts with the outside world and prohibited the construction of ocean-going ships on pain of death.[11]Contacts were maintained, however, with the Dutch through the port ofNagasaki,the Chinese also through Nagasaki and the Ryukyus and Korea through intermediaries with Tsushima. The study of Western sciences, called "rangaku"through the Dutch enclave ofDejimain Nagasaki led to the transfer of knowledge related to the Western technological andscientific revolutionwhich allowed Japan to remain aware of naval sciences, such ascartography,opticsand mechanical sciences. Seclusion, however, led to the loss of any naval and maritime traditions the nation possessed.[5]

Apart from Dutch trade ships, no other Western vessels were allowed to enter Japanese ports. A notable exception was during theNapoleonic warswhen neutral ships flew the Dutch flag. Frictions with the foreign ships, however, started from the beginning of the 19th century. TheNagasaki Harbour IncidentinvolvingHMSPhaetonin 1808, and other subsequent incidents in the following decades, led the shogunate to enact anEdict to Repel Foreign Vessels.Western ships, which were increasing their presence around Japan due to whaling and the trade with China, began to challenge the seclusion policy.[citation needed]

TheMorrison Incidentin 1837 and news of China's defeat during theOpium Warled the shogunate to repeal the law to execute foreigners, and instead to adopt the Order for the Provision of Firewood and Water. The shogunate also began to strengthen the nation's coastal defenses. Many Japanese realized that traditional ways would not be sufficient to repel further intrusions, and western knowledge was utilized through the Dutch at Dejima to reinforce Japan's capability to repel the foreigners; field guns, mortars, and firearms were obtained, and coastal defenses reinforced.Numerous attempts to open Japanended in failure, in part to Japanese resistance, until the early 1850s.[citation needed]

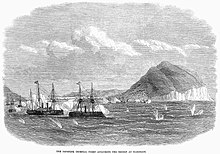

During 1853 and 1854, American warships under the command ofCommodore Matthew Perry,enteredEdo Bayand made demonstrations of force requesting trade negotiations. After two hundred years of seclusion, the 1854Convention of Kanagawaled to theopening of Japanto international trade and interaction. This was soon followed by the 1858Treaty of Amity and Commerceandtreaties with other powers.[citation needed]

-

Thesailing frigateShōhei Maru(1854) was built from Dutch technical drawings.

Development of shogunal and domain naval forces

[edit]As soon as Japan opened up to foreign influences, the Tokugawa shogunate recognized the vulnerability of the country from the sea and initiated an active policy of assimilation and adoption of Western naval technologies.[12]In 1855, with Dutch assistance, the shogunate acquired its first steam warship,Kankō Maru,and began using it for training, establishing aNaval Training Centerat Nagasaki.[12]

Samuraisuch as the future AdmiralEnomoto Takeaki(1836–1908) was sent by the shogunate to study in the Netherlands for several years.[12]In 1859 the Naval Training Center relocated toTsukijiinTokyo.In 1857 the shogunate acquired its first screw-driven steam warshipKanrin Maruand used it as an escort for the1860 Japanese delegation to the United States.In 1865 the French naval engineerLéonce Vernywas hired to build Japan's first modern naval arsenals, atYokosukaandNagasaki.[13]

The shogunate also allowed and then ordered variousdomainsto purchase warships and to develop naval fleets,[14]Satsuma,especially, had petitioned the shogunate to build modern naval vessels.[12]A naval center had been set up by the Satsuma domain in Kagoshima, students were sent abroad for training and a number of ships were acquired.[12]The domains ofChōshū,Hizen,TosaandKagajoined Satsuma in acquiring ships.[14]These naval elements proved insufficient during theRoyal Navy'sBombardment of Kagoshimain 1863 and theAllied bombardments of Shimonosekiin 1863–64.[12]

By the mid-1860s the shogunate had a fleet of eight warships and thirty-six auxiliaries.[14]Satsuma (which had the largest domain fleet) had nine steamships,[15]Choshu had five ships plus numerous auxiliary craft, Kaga had ten ships and Chikuzen eight.[15]Numerous smaller domains also had acquired a number of ships. However, these fleets resembled maritime organizations rather than actual navies with ships functioning as transports as well as combat vessels;[12]they were also manned by personnel who lacked experienced seamanship except for coastal sailing and who had virtually no combat training.[12]

-

The screw-drivensteam corvetteKanrin Maru,Japan's first screw-driven steam warship, 1857

Creation of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1868–72)

[edit]TheMeiji Restorationin 1868 led to the overthrow of the shogunate. From 1868, the newly formedMeiji governmentcontinued with reforms to centralize and modernize Japan.[17]

Boshin War

[edit]

Although the Meiji reformers had overthrown the Tokugawa shogunate, tensions between the former ruler and the restoration leaders led to theBoshin War(January 1868 to June 1869). The early part of the conflict largely involved land battles, with naval forces playing a minimal role transporting troops from western to eastern Japan.[18]Only theBattle of Awa(28 January 1868) was significant; this also proved one of the few Tokugawa successes in the war.Tokugawa Yoshinobueventually surrendered after thefall of Edoin July 1868, and as a result most of Japan accepted the emperor's rule, however resistance continuedin the North.[citation needed]

On 26 March 1868 the first naval review in Japan took place inOsaka Bay,with six ships from the private domain navies ofSaga,Chōshū,Satsuma,Kurume,KumamotoandHiroshimaparticipating. The total tonnage of these ships was 2,252 tons, which was far smaller than the tonnage of the single foreign vessel (from the French Navy) that also participated. The following year, in July 1869, the Imperial Japanese Navy was formally established, two months after the last combat of the Boshin War.[citation needed]

Enomoto Takeaki, the admiral of theshōgun's navy, refused to surrender all his ships, remitting just four vessels, and escaped to northernHonshūwith the remnants of theshōgun's navy: eight steam warships and 2,000 men. Following the defeat of pro-shogunate resistance on Honshū, Admiral Enomoto Takeaki fled toHokkaidō,where he established the breakawayRepublic of Ezo(27 January 1869). The new Meiji government dispatched a military force to defeat the rebels, culminating with theNaval Battle of Hakodatein May 1869.[19]The Imperial side took delivery (February 1869) of the French-built ironcladKotetsu(originally ordered by the Tokugawa shogunate) and used it decisively towards the end of the conflict.[20]

Consolidation

[edit]In February 1868 the Imperial government had placed all captured shogunate naval vessels under the Navy Army affairs section.[18]In the following months, military forces of the government came under the control of several organizations which were established and then disbanded until the establishment of theMinistry of Warand of theMinistry of the Navy of Japanin 1872. For the first two years (1868–1870) of the Meiji state no national, centrally controlled navy existed,[21]– the Meiji government only administered those Tokugawa vessels captured in the early phase of the Boshin War of 1868–1869.[21]All other naval vessels remained under the control of the various domains which had been acquired during theBakumatsuperiod. The naval forces mirrored the political environment of Japan at the time: the domains retained their political as well as military independence from the Imperial government.Katsu Kaishūa former Tokugawa navy leader, was brought into the government as Vice Minister of the Navy in 1872, and became the firstMinister of the Navyfrom 1873 until 1878 because of his naval experience and his ability to control Tokugawa personnel who retained positions in the government naval forces. Upon assuming office Katsu Kaishu recommended the rapid centralization of all naval forces – government and domain – under one agency.[21]The nascent Meiji government in its first years did not have the necessary political and military force to implement such a policy and so, like much of the government, the naval forces retained a decentralized structure in most of 1869 through 1870.[citation needed]

The incident involving Enomoto Takeaki's refusal to surrender and his escape to Hokkaidō with a large part of the former Tokugawa Navy's best warships embarrassed the Meiji government politically. The imperial side had to rely on considerable naval assistance from the most powerful domains as the government did not have enough naval power to put down the rebellion on its own.[21]Although the rebel forces in Hokkaidō surrendered, the government's response to the rebellion demonstrated the need for a strong centralized naval force.[17]Even before the rebellion the restoration leaders had realized the need for greater political, economic and military centralization and by August 1869 most of the domains had returned their lands and population registers to the government.[17]In 1871 the domains were abolished altogether and as with the political context the centralization of the navy began with the domains donating their forces to the central government.[17]As a result, in 1871 Japan could finally boast a centrally controlled navy, this was also the institutional beginning of the Imperial Japanese Navy.[17]

In February 1872, the Ministry of War was replaced by a separate Army Ministry and Navy Ministry. In October 1873, Katsu Kaishū became Navy Minister.[22]

Secondary Service (1872–1882)

[edit]

After the consolidation of the government the new Meiji state set about to build up national strength. The Meiji government honored the treaties with the Western powers signed during the Bakumatsu period with the ultimate goal of revising them, leading to a subsided threat from the sea. This however led to conflict with those disgruntled samurai who wanted to expel the westerners and with groups which opposed the Meiji reforms. Internal dissent – including peasant uprisings – become a greater concern for the government, which curtailed plans for naval expansion as a result. In the immediate period from 1868 many members of the Meiji coalition advocated giving preference to maritime forces over the army and saw naval strength as paramount.[19]In 1870 the new government drafted an ambitious plan to develop a navy with 200 ships organized into ten fleets. The plan was abandoned within a year due to lack of resources.[19]Financial considerations were a major factor restricting the growth of the navy during the 1870s.[23]Japan at the time was not a wealthy state. Soon, however, domestic rebellions, theSaga Rebellion(1874) and especially theSatsuma Rebellion(1877), forced the government to focus on land warfare, and the army gained prominence.[19]

Naval policy, as expressed by the sloganShusei Kokubō(literally: "Static Defense" ), focused on coastal defenses,[19]on a standing army (established with the assistance of the secondFrench Military Mission to Japan), and a coastal navy that could act in a supportive role to drive an invading enemy from the coast. The resulting military organization followed theRikushu Kaijū(Army first, Navy second) principle.[19]This meant a defense designed to repel an enemy from Japanese territory, and the chief responsibility for that mission rested upon Japan's army; consequently, the army gained the bulk of the military expenditures.[24]During the 1870s and 1880s, the Imperial Japanese Navy remained an essentially coastal-defense force, although the Meiji government continued to modernize it.Jo Sho Maru(soon renamedRyūjō Maru) commissioned byThomas Gloverwas launched atAberdeen,Scotlandon 27 March 1869.[citation needed]

British support and influence

[edit]

In 1870 an Imperial decree determined that Britain's Royal Navy should serve as the model for development, instead of the Netherlands navy.[25]In 1873 a thirty-four-man British naval mission, headed byLt. Comdr. Archibald Douglas,arrived in Japan. Douglas directed instruction at the Naval Academy at Tsukiji for several years, the mission remained in Japan until 1879, substantially advancing the development of the navy and firmly establishing British traditions within the Japanese navy from matters of seamanship to the style of its uniforms and the attitudes of its officers.[25]

From September 1870, the English Lieutenant Horse, a former gunnery instructor for theSaga fiefduring the Bakumatsu period, was put in charge of gunnery practice on board theRyūjō.In 1871, the ministry resolved to send 16 trainees abroad for training in naval sciences (14 to Great Britain, two to the United States), among whom was Heihachirō Tōgō. In 1879,Commander L. P. Willanwas hired to train naval cadets.[25]

Ships such as theFusō,KongōandHieiwere built in British shipyards, and they were the first warships built abroad specifically for the Imperial Japanese Navy.[23][26]Private construction companies such asIshikawajimaandKawasakialso emerged around this time.[citation needed]

First interventions abroad (Taiwan 1874, Korea 1875–76)

[edit]During 1873, a plan to invade theKorean Peninsula,theSeikanronproposal made bySaigō Takamori,was narrowly abandoned by decision of the central government in Tokyo.[27]In 1874, theTaiwan expeditionwas the first foray abroad of the new Imperial Japanese Navy andArmyafter theMudan Incident of 1871,however the navy served largely as a transport force.[24]

Various interventions in the Korean Peninsula continued in 1875–1876, starting with theGanghwa Island incidentprovoked by the Japanese gunboatUn'yō,leading to the dispatch of a large force of the Imperial Japanese Navy. As a result, theJapan–Korea Treaty of 1876was signed, marking the official opening of Korea to foreign trade, and Japan's first example of Western-style interventionism and adoption of "unequal treaties" tactics.[28]

In 1878, the Japanese cruiserSeikisailed to Europe with an entirely Japanese crew.[citation needed]

Naval expansion (1882–1893)

[edit]

First naval expansion bill

[edit]After theImo Incidentin July 1882,Iwakura Tomomisubmitted a document to thedaijō-kantitled "Opinions Regarding Naval Expansion" asserting that a strong navy was essential to maintaining the security of Japan.[29]In furthering his argument, Iwakura suggested that domestic rebellions were no longer Japan's primary military concern and that naval affairs should take precedence over army concerns; a strong navy was more important than a sizable army to preserve the Japanese state.[29]Furthermore, he justified that a large, modern navy, would have the added potential benefit of instilling Japan with greater international prestige[29]and recognition, as navies were internationally recognized hallmarks of power and status.[30]Iwakura also suggested that the Meiji government could support naval growth by increasing taxes on tobacco, sake, and soy.[30]

After lengthy discussions, Iwakura eventually convinced the ruling coalition to support Japan's first multi-year naval expansion plan in history.[30]In May 1883, the government approved a plan that, when completed, would add 32 warships over eight years at a cost of just over ¥26 million.[30]This development was very significant for the navy, as the amount allocated virtually equaled the navy's entire budget between 1873 and 1882.[30]The 1882 naval expansion plan succeeded in a large part because of Satsuma power, influence, and patronage.[31]Between 19 August and 23 November 1882, Satsuma forces with Iwakura's leadership, worked tirelessly to secure support for the Navy's expansion plan.[31]After uniting the other Satsuma members of the Dajokan, Iwakura approached the emperor theMeiji emperorarguing persuasively just as he did with the Dajokan, that naval expansion was critical to Japan's security and that the standing army of forty thousand men was more than sufficient for domestic purposes.[31]While the government should direct the lion's share of future military appropriations toward naval matters, a powerful navy would legitimize an increase in tax revenue.[32]On November 24, the emperor assembled select ministers of thedaijō-kantogether with military officers, and announced the need for increased tax revenues to provide adequate funding for military expansion, this was followed by an imperial re-script. The following month, in December, an annual ¥7.5-million tax increase on sake, soy, and tobacco was fully approved, in the hopes that it would provide ¥3.5 million annually for warship construction and ¥2.5 million for warship maintenance.[32]In February 1883, the government directed further revenues from other ministries to support an increase in the navy's warship construction and purchasing budget. By March 1883, the navy secured the ¥6.5 million required annually to support an eight-year expansion plan, this was the largest that the Imperial Japanese Navy had secured in its young existence.[32]

However, naval expansion remained a highly contentious issue for both the government and the navy throughout much of the 1880s. Overseas advances in naval technology increased the costs of purchasing large components of a modern fleet, so that by 1885 cost overruns had jeopardized the entire 1883 plan. Furthermore, increased costs coupled with decreased domestic tax revenues, heightened concern and political tension in Japan regarding funding naval expansion.[30] In 1883, two large warships were ordered from British shipyards.[citation needed]

TheNaniwaandTakachihowere 3,650 ton ships. They were capable of speeds up to 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph) and were armed with 54 to 76 mm (2 to 3 in) deck armor and two 260 mm (10 in)Kruppguns. The naval architect Sasō Sachū designed these on the line of the Elswick class ofprotected cruisersbut with superior specifications.[33]Anarms racewas taking place withChinahowever, who equipped herself with two 7,335 ton German-builtbattleships(Ting YüanandChen-Yüan). Unable to confront the Chinese fleet with only two modern cruisers, Japan resorted to French assistance to build a large, modern fleet which could prevail in the upcoming conflict.[33]

Influence of the French "Jeune École" (1880s)

[edit]

During the 1880s, France took the lead in influence, due to its "Jeune École"(" young school ") doctrine, favoring small, fast warships, especiallycruisersandtorpedo boats,against bigger units.[33]The choice of France may also have been influenced by the Minister of the Navy, who happened to be Enomoto Takeaki at that time (Navy Minister 1880–1885), a former ally of the French during the Boshin War. Also, Japan was uneasy with being dependent on Great Britain, at a time when Great Britain was very close to China.[34]

TheMeijigovernment issued its First Naval Expansion bill in 1882, requiring the construction of 48 warships, of which 22 were to be torpedo boats.[33]The naval successes of theFrench Navyagainst China in theSino-French Warof 1883–85 seemed to validate the potential of torpedo boats, an approach which was also attractive to the limited resources of Japan.[33]In 1885, the new Navy slogan becameKaikoku Nippon(Jp: Hải quốc nhật bổn, "Maritime Japan" ).[35]

In 1885, the leading French Navy engineerÉmile Bertinwas hired for four years to reinforce the Japanese Navy and to direct the construction of the arsenals ofKureandSasebo.[33]He developed theSankeikanclass of cruisers; three units featuring a single powerful main gun, the 320 mm (13 in)Canet gun.[33]Altogether, Bertin supervised the building of more than 20 units. They helped establish the first true modern naval force of Japan. It allowed Japan to achieve mastery in the building of large units, since some of the ships were imported, and some others were built domestically at the arsenal of Yokosuka:

- 3 cruisers: the 4,700 tonMatsushimaandItsukushima,built in France, and theHashidate,built at Yokosuka.[34]

- 3 coastal warships of 4,278 tons.[citation needed]

- 2 small cruisers: theChiyoda,a small cruiser of 2,439 tons built in Britain, and theYaeyama,1,800 tons, built at Yokosuka.[citation needed]

- 1frigate,the 1,600 tonTakao,built at Yokosuka.[36]

- 1aviso:the 726 tonChishima,built in France.[citation needed]

- 16 torpedo boats of 54 tons each, built in France by theCompanie du Creusotin 1888, and assembled in Japan.[34]

This period also allowed Japan "to embrace the revolutionary new technologies embodied intorpedoes,torpedo-boats andmines,of which the French at the time were probably the world's best exponents ".[37]Japan acquired its first torpedoes in 1884, and established a "Torpedo Training Center" at Yokosuka in 1886.[33]

These ships, ordered during the fiscal years 1885 and 1886, were the last major orders placed with France. The unexplained sinking ofUnebien routefrom France to Japan in December 1886, created embarrassment however.[34][38]

British shipbuilding

[edit]

Japan turned again to Britain, with the order of a revolutionary torpedo boat,Kotaka,which was considered the first effective design of a destroyer,[33]in 1887 and with the purchase ofYoshino,built at theArmstrongworks inElswick,Newcastle upon Tyne,the fastest cruiser in the world at the time of her launch in 1892.[33]In 1889, she ordered theClyde-builtChiyoda,which defined the type forarmored cruisers.[39]

Between 1882 and 1918, ending with the visit of theFrench Military Mission to Japan,the Imperial Japanese Navy stopped relying on foreign instructors altogether. In 1886, she manufactured her ownprismatic powder,and in 1892 one of her officers invented a powerful explosive, theShimose powder.[citation needed]

First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

[edit]Japan continued the modernization of its navy, especially as China was also building a powerful modern fleet with foreign, especially German, assistance, and as a result tensions were building between the two countries over Korea. The Japanese naval leadership on the eve of hostilities, was generally cautious and even apprehensive[40]as the navy had not yet received the warships ordered in February 1893, particularly the battleshipsFujiandYashimaand the cruiserAkashi.[41]Hence, initiating hostilities at the time was not ideal, and the navy was far less confident than the Japanese army about the outcome of a war with China.[40]

Japan's main strategy was to gain command of the sea as this was critical to the operations on land. An early victory over the Beiyang fleet would allow Japan to transport troops and material to the Korean Peninsula, however any prolongation of the war would increase the risk of intervention by the European powers with interests in East Asia.[42]The army'sFifth Divisionwould land at Chemulpo on the western coast of Korea, both to engage and push Chinese forces northwest up the peninsula and to draw the Beiyang Fleet into the Yellow Sea, where it would be engaged in decisive battle. Depending upon the outcome of this engagement, Japan would make one of three choices; If the Combined Fleet were to win decisively, the larger part of the Japanese army would undertake immediate landings on the coast betweenShanhaiguanandTianjinin order to defeat the Chinese army and bring the war to a swift conclusion. If the engagement were to be a draw and neither side gained control of the sea, the army would concentrate on the occupation of Korea. Lastly, if the Combined Fleet was defeated and consequently lost command of the sea, the bulk of the army would remain in Japan and prepare to repel a Chinese invasion, while the Fifth Division in Korea would be ordered to hang on and fight a rearguard action.[43]

A Japanese squadron intercepted and defeated a Chinese force near Korean islandof Pungdo;damaging a cruiser, sinking a loaded transport, capturing one gunboat and destroying another.[43]The battle occurred beforethe warwas officially declared on 1 August 1894.[43]On August 10, the Japanese ventured into the Yellow Sea to seek out the Beiyang Fleet and bombarded bothWeihaiweiand Port Arthur. Finding only small vessels in either harbor, the Combined Fleet returned to Korea to support further landings off the Chinese coast. The Beiyang Fleet under the command of Admiral Ding was initially ordered to stay close to the Chinese coast while reinforcements were sent to Korea by land. But as Japanese troops had very quickly advanced northward from Seoul to Pyongyang the Chinese decided to rush troops to Korea by sea under a naval escort, in mid-September.[44] Concurrently, because there had been no decisive encounter at sea, the Japanese decided to send more troops to Korea. Early in September, the navy was directed to support further landings and to support the army on Korea's western coast. As Japanese ground forces then moved north to attack Pyongyang, Admiral Ito correctly guessed that the Chinese would attempt to reinforce their army in Korea by sea. On 14 September, the Combined Fleet went north to search the Korean and Chinese coasts and to bring the Beiyang Fleet to battle. On 17 September 1894, the Japanese encountered them off the mouth of theYalu River.The Combined Fleet then devastated theBeiyang Fleetduring thebattle,in which the Chinese fleet lost eight out of 12 warships.[45]The Chinese subsequently retreated behind the Weihaiwei fortifications. However, they were then surprised by Japanese troops, who outflanked the harbour's defenses in coordination with the navy.[45]The remnants of the Beiyang Fleet were destroyed atWeihaiwei.Although Japan turned out victorious, the two large German-made Chinese ironclad battleships (DingyuanandZhenyuan) remained almost impervious to Japanese guns, highlighting the need for bigger capital ships in the Imperial Japanese Navy. The next step of the Imperial Japanese Navy's expansion would thus involve a combination of heavily armed large warships, with smaller and innovative offensive units permitting aggressive tactics.[46]

As a result of the conflict, under theTreaty of Shimonoseki(April 17, 1895),Taiwanand thePescadores Islandswere transferred to Japan.[47]The Imperial Japanese Navy took possession of the island and quelled opposition movements between March and October 1895. Japan also obtained theLiaodong Peninsula,although she was forced by Russia, Germany and France to return it to China (Triple Intervention), only to see Russia take possession of it soon after.[citation needed]

Suppression of the Boxer rebellion (1900)

[edit]The Imperial Japanese Navy further intervened in China in 1900 by participating, together with Western Powers, in the suppression of the ChineseBoxer Rebellion.The Navy supplied the largest number of warships (18 out of a total of 50) and delivered the largest contingent of troops among the intervening nations (20,840 Imperial Japanese Army and Navy soldiers, out of a total of 54,000).[48][49]

The conflict allowed Japan to enter combat together with Western nations and to acquire first-hand understanding of their fighting methods.[citation needed]

Naval buildup and tensions with Russia

[edit]

Following the war against China, the Triple Intervention under Russian leadership, pressured Japan to renounce its claim to the Liaodong Peninsula. The Japanese were well aware of the naval power the three countries possessed in East Asian waters, particularly Russia.[50]Faced with little choice the Japanese retroceded the territory back to China for an additional 30 million taels (roughly ¥45 million). With the humiliation of the forced return of the Liaodong Peninsula, Japan began to build up its military strength in preparation for future confrontations.[51]The political capital and public support for the navy gained as a result of the recent conflict with China, also encouraged popular and legislative support for naval expansion.[50]

In 1895,Yamamoto Gombeiwas assigned to compose a study of Japan's future naval needs.[50]He believed that Japan should have sufficient naval strength to not only to deal with a single hypothetical enemy separately, but to also confront any fleet from two combined powers that might be dispatched against Japan from overseas waters.[52]He assumed that with their conflicting global interests, it was highly unlikely that the British and Russians would ever join together in a war against Japan,[52]considering it more likely that a major power like Russia in alliance with a lesser naval power, would dispatch a portion of their fleet against Japan. Yamamoto therefore calculated that four battleships would be the main battle force that a major power could divert from their other naval commitments to use against Japan and he also added two more battleships that might be contributed to such a naval expedition by a lesser hostile power. In order to achieve victory Japan should have a force of six of the largest battleships supplemented by four armored cruisers of at least 7,000 tons.[53]The centerpiece of this expansion was to be the acquisition of four new battleships in addition to the two which were already being completed in Britain being part of an earlier construction program. Yamamoto was also advocating the construction of a balanced fleet.[54]

Battleships would be supplemented by lesser warships of various types, including cruisers that could seek out and pursue the enemy and a sufficient number of destroyers and torpedo boats capable of striking the enemy in home ports. As a result, the program also included the construction of twenty-three destroyers, sixty-three torpedo boats, and an expansion of Japanese shipyards and repair and training facilities.[52]In 1897, because of fears that the size of the Russian fleet assigned to East Asian waters could be larger than previously believed, the plan was revised. Although budgetary limitations simply could not permit the construction of another battleship squadron, the newHarveyandKC armorplates could resist all but the largestAP shells.Japan could now acquire armored cruisers that could take the place in the battle line. Hence, with new armor and lighter but more powerful quick-firing guns, this new cruiser type was superior to many older battleships still afloat.[55]Subsequently, the revisions to the ten-year plan led to the four protected cruisers being replaced by an additional two armored cruisers. As a consequence the"Six-Six Fleet"was born, with six battleships and six armored cruisers.[55]

The program for a 260,000-ton navy to be completed over a ten-year period in two stages of construction, with the total cost being ¥280 million, was approved by the cabinet in late 1895 and funded by the Diet in early 1896.[55]Of the total warship acquisitions accounted for just over ¥200 million.[51]The first stage would begin in 1896 and be completed by 1902; the second would run from 1897 to 1905. The program was financed significantly from the Chinese indemnity secured after the First Sino-Japanese War.[56]This was used to fund the bulk of the naval expansion, roughly ¥139 million, with public loans and existing government revenue providing the rest of the financing required over the ten years of the program.[56]Japan's industrial resources at the time were inadequate for the construction of a fleet of armored warships domestically, as the country was still in the process of developing and acquiring the industrial infrastructure for the construction of major naval vessels. Consequently, the overwhelming majority was built in British shipyards.[55]With the completion of the fleet, Japan would become the fourth strongest naval power in the world in a single decade.[55]In 1902, Japan formedan alliance with Britain,the terms of which stated that if Japan went to war in the Far East and that a third power entered the fight against Japan, then Britain would come to the aid of the Japanese.[57]This was a check to prevent any third power from intervening militarily in any future war with Russia.

Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905)

[edit]

The new fleet consisted of:[58]

- 6battleships(all British-built)

- 8armored cruisers(4 British-, 2 Italian-, 1 German-builtYakumo,and 1 French-builtAzuma)

- 9cruisers(5 Japanese, 2 British and 2 US-built)

- 24destroyers(16 British- and 8 Japanese-built)

- 63torpedo boats(26 German-, 10 British-, 17 French-, and 10 Japanese-built)

One of these battleships,Mikasa,which was among the most powerful warships afloat when completed,[59]was ordered from theVickersshipyard in the United Kingdom at the end of 1898, for delivery to Japan in 1902. Commercial shipbuilding in Japan was exhibited by construction of the twin screw steamerAki-Maru,built forNippon Yusen Kaishaby theMitsubishiDockyard & Engine Works, Nagasaki. The Imperial Japanese cruiserChitosewas built at theUnion Iron WorksinSan Francisco,California.[citation needed]

These dispositions culminated with theRusso-Japanese War.At theBattle of Tsushima,Admiral Togo (flag inMikasa) led the Japanese Grand Fleet into the decisive engagement of the war.[60][61]The Russian fleet was almost completely annihilated: out of 38 Russian ships, 21 were sunk, seven captured, six disarmed, 4,545 Russian servicemen died and 6,106 were taken prisoner. On the other hand, the Japanese only lost 116 men and three torpedo boats.[62]These victories broke Russian strength inEast Asia,and triggered waves of mutinies in the Russian Navy atSevastopol,VladivostokandKronstadt,peaking in June with thePotemkinuprising,thereby contributing to theRussian Revolution of 1905.The victory at Tsushima elevated the stature of the navy.[63]

The Imperial Japanese Navy acquired its first submarines in 1905 fromElectric Boat Company,barely four years after the US Navy had commissioned its own first submarine,USSHolland.The ships wereHollanddesigns and were developed under the supervision of Electric Boat's representative,Arthur L. Busch.These five submarines (known as Holland Type VII's) were shipped in kit form to Japan (October 1904) and then assembled at the Yokosuka, KanagawaYokosuka Naval Arsenal,to become hullsNo.1through5,and became operational at the end of 1905.[64]

Towards an autonomous national navy (1905–1914)

[edit]

Japan continued in its efforts to build up a strong national naval industry. Following a strategy of "copy, improve, innovate",[65]foreign ships of various designs were usually analysed in depth, their specifications often improved on, and then were purchased in pairs so as to organize comparative testing and improvements. Over the years, the importation of whole classes of ships was progressively substituted by local assembly, and then complete local production, starting with the smallest ships, such as torpedo boats and cruisers in the 1880s, to finish with whole battleships in the early 20th century. The last major purchase was in 1913 when thebattlecruiserKongōwas purchased from the Vickers shipyard. By 1918, there was no aspect of shipbuilding technology where Japanese capabilities fell significantly below world standards.[66]

The period immediately after Tsushima also saw the IJN, under the influence of thenavalisttheoreticianSatō Tetsutarō,adopt an explicit policy of building for a potential future conflict against the US Navy. Satō called for a battlefleet at least 70% as strong as that of the US. In 1907, the official policy of the Navy became an 'eight-eight fleet' of eight modern battleships and eight battlecruisers. However, financial constraints prevented this ideal ever becoming a reality.[67]

By 1920, the Imperial Japanese Navy was the world's third largest navy and a leader in naval development:

- Following its 1897 invention byMarconi,the Japanese Navy was the first navy to employwireless telegraphyin combat, at the 1905 Battle of Tsushima.[68]

- In 1905, it began building the battleshipSatsuma,at the time the largest warship in the world by displacement, and the first ship to be designed, ordered and laid down as an "all-big-gun" battleship, about one year prior to the launching ofHMSDreadnought.However, due to a lack of material, she was completed with a mixed battery of rifles, launched on 15 November 1906, and completed on 25 March 1910.[69][70]

- Between 1903[69]and 1910, Japan began to build battleships domestically. The 1906 battleshipSatsumawas built in Japan with about 80% material imported from Great Britain, with the following battleship class in 1909,[71]theKawachi,being built with only 20% imported parts.

World War I (1914–1918)

[edit]

Japan enteredWorld War Ion the side of theEntente,againstGermanyandAustria-Hungary,as a consequence of the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance. In theSiege of Tsingtao,the Imperial Japanese Navy helped seize the German colony atJiaozhou Bay.During the siege, beginning on 5 September 1914,Wakamiyaconducted the world's first successful sea-launched air strikes. On 6 September 1914, in the very first air-sea battle in history, a Farman aircraft launched byWakamiyaattacked the Austro-Hungarian cruiserKaiserin Elisabethand the German gunboatJaguaroffQingdao.[72]fromJiaozhou Bay.FourMaurice Farmanseaplanes bombarded German land targets like communication and command centers, and damaged a German minelayer in the Tsingtao peninsula from September to 6 November 1914 when the Germans surrendered.[73]

A battle group was also sent to the central Pacific in August and September to pursue the GermanEast Asia squadron,which then moved into the Southern Atlantic, where it encountered British naval forces and was destroyed at theFalkland Islands.Japan also seized German possessions innorthern Micronesia,which remained Japanese colonies until the end of World War II, under theLeague of Nations'South Seas Mandate.[74]Hard pressed in Europe, where she had only a narrow margin of superiority against Germany, Britain had requested, but was denied, the loan of Japan's four newly builtKongō-classbattlecruisers (Kongō,Hiei,Haruna,andKirishima), some of the first ships in the world to be equipped with 356 mm (14 in) guns, and the most formidable battlecruisers in the world at the time.[75]

Following a further request by the British and the initiation ofunrestricted submarine warfareby Germany, in March 1917, the Japanese sent aspecial forceto the Mediterranean. This force, consisted of one protected cruiser,Akashiasflotilla leaderand eight of the Navy's newestKaba-class destroyers(Ume,Kusunoki,Kaede,Katsura,Kashiwa,Matsu,Sugi,andSakaki), under Admiral Satō Kōzō, was based inMaltaand efficiently protected allied shipping betweenMarseille,Taranto,and ports inEgyptuntil the end of the War.[76]In June,Akashiwas replaced byIzumo,and four more destroyers were added (Kashi,Hinoki,Momo,andYanagi). They were later joined by the cruiserNisshin.By the end of the war, the Japanese had escorted 788 allied transports. One destroyer,Sakaki,was torpedoed on 11 June 1917 by a German submarine with the loss of 59 officers and men. A memorial at the Kalkara Naval Cemetery in Malta was dedicated to the 72 Japanese sailors who died in action during the Mediterranean convoy patrols.[77]

In 1917, Japan exported 12Arabe-class destroyersto France. In 1918, ships such asAzumawere assigned toconvoyescort in theIndian OceanbetweenSingaporeand theSuez Canalas part of Japan's contribution to the war effort under theAnglo-Japanese alliance.After the conflict, the Japanese Navy received seven German submarines as spoils of war, which were brought to Japan and analysed, contributing greatly to the development of the Japanese submarine industry.[78]

Interwar years (1918–1937)

[edit]

By 1921, Japan's naval expenditure reached nearly 32% of the national government budget.

Washington treaty system

[edit]In the years following after the end of First World War the naval construction programs of the three greatest naval powers Britain, Japan and the United States had threatened to set off a new potentially dangerous and expensive naval arms race.[79]The subsequent Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 became one of history's most effective arms reduction programs,[80]setting up a system of ratios between the five signatory powers. The United States and Britain were each allocated 525,000 tons of capital ships, Japan 315,000, and France and Italy to 175,000, ratios of 5:3:1.75.[81]Also agreed to was a ten-year moratorium on battleship construction, though replacement of battleships reaching 20 years of service was permitted. Maximum limits of 35,000 tons and 16-inch guns were also set. Carriers were restricted with the same 5:5:3 ratio, with Japan allotted 81,000 tons.[81]

Many naval leaders in Japan's delegation were outraged by these limitations, as Japan would always be behind its chief rivals. However, in the end it was concluded that even these unfavorable limitations would be better than an unrestricted arms race with the industrially dominant United States.[82]The Washington System may have made Japan a junior partner with the US and Britain, but it also curtailed the rise of China and the Soviet Union, who both sought to challenge Japan in Asia.[83]

The Washington Treaty did not restrict the building of ships other than battleships and carriers, resulting in a building race for heavy cruisers. These were limited to 10,000 tons and 8-inch guns.[84]The Japanese were also able to get some concessions, most notably the battleshipMutsu,[85]which had been partly funded by donations from schoolchildren and would have been scrapped under the terms of the treaty.

The Treaty also dictated that the United States, Britain, and Japan could not expand their Western Pacific fortifications. Japan specifically could not militarize the Kurile Islands, the Bonin Islands, Amami-Oshima, the Loochoo Islands, Formosa and the Pescadores.[86]

Development of naval aviation

[edit]

Japan at times continued to solicit foreign expertise in areas in which the IJN was inexperienced, such as naval aviation. The Japanese navy had closely monitored the progress of aviation of the three Allied naval powers during World War I and concluded that Britain had made the greatest advances in naval aviation,.[87]TheSempill Missionled byCaptain William Forbes-Sempill,a former officer in theRoyal Air Forceexperienced in the design and testing of Royal Navy aircraft during the First World War.[88]The mission consisted of 27 members, who were largely personnel with experience in naval aviation and included pilots and engineers from several British aircraft manufacturing firms.[88]The British technical mission left for Japan in September with the objective of helping the Imperial Japanese Navy develop and improve the proficiency of its naval air arm.[88]The mission arrived at Kasumigaura Naval Air Station the following month, in November 1921, and stayed in Japan for 18 months.[89]

The mission brought to Kasumigaura well over a hundred British aircraft comprising twenty different models, five of which were then currently in service with the Royal Navy'sFleet Air Arm.The Japanese were trained on several, such as theGloster Sparrowhawk,then a frontline fighter. The Japanese would go on to order 50 of these aircraft from Gloster, and build 40.[90]These planes eventually provided the inspiration for the design of a number of Japanese naval aircraft. Technicians become familiar with the newest aerial weapons and equipment-torpedoes, bombs, machine guns, cameras, and communications gear.[88]

The mission also brought the plans of the most recent British aircraft carriers, such as HMSArgusand HMSHermes,which influenced the final stages of the development of the carrierHōshō.By the time its last members had returned to Britain, the Japanese had acquired a reasonable grasp of the latest aviation technology and taken the first steps toward having an effective naval air force.[91]Japanese naval aviation also, both in technology and in doctrine, continued to be dependent on the British model for most of the 1920s.[92]

Naval developments during the interwar years

[edit]

Between the wars, Japan took the lead in many areas of warship development:

- In 1921, it launchedHōshō,the first purpose-designedaircraft carrierin the world to be completed, and subsequently developed a fleet of aircraft carriers second to none.

- In keeping with its doctrine, the Imperial Japanese Navy was the first to mount 356 mm (14 in) guns (inKongō), 410 mm (16.1 in) guns (inNagato), and began the only battleships ever to mount460 mm (18.1 in) guns(in theYamatoclass).[93]

- In 1928, she launched the innovativeFubuki-classdestroyer,introducing enclosed dual 127 mm (5 in) turrets capable of anti-aircraft fire. The new destroyer design was soon emulated by other navies. TheFubukis also featured the firsttorpedo tubesenclosed in splinter proofturrets.[94]

- Japan developed the 610 mm (24 in) oxygen fuelledType 93 torpedo,generally recognized as the best torpedo of World War Two.[95]

Doctrinal debates

[edit]The Imperial Japanese Navy was faced before and during World War II with considerable challenges, probably more so than any other navy in the world.[96]Japan, like Britain, was almost entirely dependent on foreign resources to supply its economy. To achieve Japan's expansionist policies, the IJN had to secure and protect distant sources of raw material (especially Southeast Asian oil and raw materials), controlled by foreign countries (Britain, France, andthe Netherlands). To achieve this goal, she had to build large warships capable of long range operations. In theyears beforeWorld War II,the IJN began to structure itself specifically to fight the United States. A long stretch ofmilitaristicexpansion and the start of theSecond Sino-Japanese Warin 1937 had exacerbated tensions with the United States, which was seen as a rival of Japan.

This was in conflict with Japan's doctrine of "decisive battle" (Hạm đội quyết chiến,Kantai kessen,which did not require long range),[97]in which the IJN would allow the US to sail across the Pacific, using submarines to harass the enemy fleet, then engage the US Navy in a "decisive battle area" near Japan after inflicting suchattrition.[98]This is also in keeping with the theory ofAlfred T. Mahan,to which every major navy subscribed before World War II, in which wars would be decided by engagements between opposing surface fleets.[99]

Following the dictates of Satō (who doubtless was influenced by Mahan),[100]it was the basis for Japan's demand for a 70% ratio (10:10:7) at theWashington Naval Conference,which would give Japan superiority in the "decisive battle area", and the US' insistence on a 60% ratio, which meant parity.[101]

It was also in conflict with her past experience. Japan's numerical and industrial inferiority led her to seek technical superiority (fewer, but faster, more powerful ships), qualitative superiority (better training), and aggressive tactics (daring and speedy attacks overwhelming the enemy, a recipe for success in her previous conflicts), but failed to take account of any of these traits. Her opponents in any futurePacific Warwould not face the political and geographical constraints of her previous wars, nor did she allow for losses in ships and crews.[102]

During the inter-war years, two schools of thought contested over whether the navy should be organized around powerful battleships (ultimately able to defeat equivalent American ships in Japanese waters), or aircraft carriers. Neither doctrine prevailed, and a balanced yet indecisive approach to capital ship development reigned.

A consistent weakness of gunned Japanese warship development was the tendency to incorporate excessive firepower and engine output relative to ship size (a side-effect of the Washington Treaty limitations on overall tonnage). This led to shortcomings in stability, protection, and structural strength.[103]

Circle Plans

[edit]

In response to theLondon Treaty of 1930,the Japanese started a series of naval construction programs orhoju keikaku(naval replenishment, or construction, plans), known unofficially as themaru keikaku(circle plans). Between 1930 and the outbreak of the Second World War there were four of these"Circle plans"which were drawn up in 1931, 1934, 1937, and 1939.[104]TheCircle Onewas plan approved in 1931, provided for the construction of 39 ships to be laid down between 1931 and 1934, centering on four of the newMogami-classcruisers,[105]and expansion of theNaval Air Serviceto 14 Air Groups. However, plans for a secondCircle planwere delayed by theTomozurucapsizing and heavy typhoon damage to theFourth fleet,when it was revealed that the fundamental design philosophy of many Japanese warships was flawed. largely due to poor construction techniques and instability caused by attempting to mount too much weaponry on too small a displacement hull.[106]As a result, most of the naval budget in 1932–1933 was absorbed in modifications to rectify the issues with existing equipment.[106]

In 1934, theCircle Twoplan was approved, covering the construction of 48 new warships including theTone-class cruisersand two carriers:SōryūandHiryū.The plan also continued the buildup in naval aircraft and authorized the creation of eight new Naval Air Groups. With Japan's renunciation of naval treaties in December 1934,Circle Threeplan was approved in 1937, its third major naval building program since 1930.[107]A six-year effort that called for the construction of new warships that were free from the restrictions of previous naval treaties. Concentrating on qualitative superiority to compensate for Japan's quantitative deficiencies compared with the United States. While the core ofCircle threewas to be the construction of the two battleshipsYamatoandMusashi,it also called for building the twoShōkaku-classaircraft carrier, along with sixty-four other warships in other categories.[107]Circle Threealso called for the rearming of the demilitarized battlecruiserHieiand the refitting of her sister ships,Kongō,Haruna,andKirishima.[107]Also funded was the upgrading of fourMogami-class cruisers and twoToneclass cruisers, which were under construction, by replacing their 6-inch main batteries with 8-inch guns.[107]In aviation,Circle Threeaimed at maintaining parity with American naval air power by adding 827 planes for allocation to fourteen planned land-based air groups, and increasing carrier aircraft by nearly 1,000. To accommodate the new land aircraft the plan called for several new airfields to be built or expanded; it also provided for a significant increase in the size of the navy's production facilities for aircraft and aerial weapons.[107]

In 1938, with the construction ofCircle Threeunder way, the Japanese had started to consider preparations for the next major expansion, which was scheduled for 1940. However, with the Americansecond Vinson actin 1938, the Japanese accelerated theCircle Foursix-year expansion program, which was approved in September 1939.[108]Circle Four'sgoal was doubling Japan's naval air strength in just five years, delivering air superiority in East Asia and the western Pacific.[108]It called for the building of twoYamato-classbattleship, a fleet carrier, six of a new class of planned escort carriers, six cruisers, twenty-two destroyers, and twenty-five submarines.

Second Sino-Japanese War

[edit]

The Second Sino-Japanese War was of great importance and value to the development of Japanese naval aviation, demonstrating how aircraft could contribute to the projection of naval power ashore.[109]

The IJN had two primary responsibilities during the campaign: to support amphibious operations on the Chinese coast and the strategic aerial bombardment of Chinese cities[110]– the first time any naval air arm had been given such tasks.[110]

From the onset of hostilities in 1937 until forces were diverted to combat for the Pacific war in 1941, naval aircraft played a key role in military operations on the Chinese mainland. These began with attacks on military installations largely in the Yangtze River basin along the Chinese coast by Japanese carrier aircraft.[110]Naval involvement during the conflict peaked in 1938–39 with the heavy bombardment of Chinese cities deep in the interior by land-based medium bombers and concluded during 1941 with an attempt by both, carrier-borne and land-based, tactical aircraft to cut communication and transportation routes in southern China. Although, the 1937–41 air offensives failed in their political and psychological aims, they did reduce the flow of strategic materiel to China and for a time improved the Japanese military situation in the central and southern parts of the country.[110]

World War II

[edit]| IJN vs USN shipbuilding (1937–1945, inStandard Tons Displacement)[111] | ||

| Year | IJN | USN |

| 1937 | 45,000 | 75,000 |

| 1938 | 40,000 | 80,000 |

| 1939 | 35,000 | 70,000 |

| 1940 | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| 1941 | 180,000 | 130,000 |

| 1942–45 | 550,000 | 3,200,000 |

To effectively combat the numerically superior American navy, the Japanese had devoted a large amount of resources to create a force of superior quality.[112][107][113]Betting on the success of aggressive tactics which stemmed fromMahanian doctrineand the concept of decisive battle,[114]Japan did not invest significantly in capabilities needed to protect its long shipping lines against enemy submarines,[115]particularly under-investing in the vital area ofantisubmarine warfare(both escort ships andescort carriers), and in the specialized training and organization to support it.[116]Imperial Japan's reluctance to use itssubmarinefleet for commerce raiding and failure to secure its communications also hastened its defeat.[citation needed]The Japanese Navy also underinvested in intelligence and had hardly any agents active in the United States when the war started; several Japanese Naval officers credited lack of information about the US Navy as another major factor in their defeat.[117]

The IJN launched a surpriseattack on Pearl Harbor,killing 2,403 Americans and crippling the US Pacific Fleet.[118]During the first six months of the Pacific War, the IJN enjoyed spectacular success inflicting heavy defeats on Allied forces.[119]Allied navies were devastated during the Japanese conquest of Southeast Asia.[120]Japanese naval aircraft were also responsible for thesinkings of HMSPrince of Walesand HMSRepulsewhich was the first time that capital ships were sunk by aerial attack while underway.[121]In April 1942, theIndian Ocean raiddrove the Royal Navy from South East Asia.[122]

After these successes, the IJN now concentrated on the elimination and neutralization of strategic points from where the Allies could launch counteroffensives against Japanese conquests.[120]However, atCoral Seathe Japanese were forced to abandon their attempts to isolate Australia[120]while the defeat in theMidway Campaignsaw the Japanese forced on the defensive. Thecampaign in the Solomon Islands,in which the Japanese lost the war of attrition, was the most decisive; the Japanese failed to commit enough forces in sufficient time.[123]During 1943 the Allies were able to reorganize their forces and American industrial strength began to turn the tide of the war.[124]American forces ultimately managed to gain the upper hand through a vastly greater industrial output and a modernization of its air and naval forces.[125]

In 1943, the Japanese also turned their attention to the defensive perimeters of their previous conquests. Forces on Japanese held islands in Micronesia were to absorb and wear down an expected American counteroffensive.[124]However, American industrial power become apparent and the military forces that faced the Japanese in 1943 were overwhelming in firepower and equipment.[124]From the end of 1943 to 1944 Japan's defensive perimeter failed to hold.[124]

The defeat at thePhilippine Seawas a disaster for Japanese naval air power with American pilots terming the slanted air/sea battle theGreat Marianas Turkey Shoot,mostly going in the favor of the US,[126]while thebattle of Leyte Gulfled to the destruction of a large part of the surface fleet.[127]During the last phase of the war, the Imperial Japanese Navy resorted to a series of desperate measures, including a variety ofSpecial Attack Unitswhich were popularly calledkamikaze.[128]By May 1945, most of the Imperial Japanese Navy had been sunk and the remnants had taken refuge in Japan's harbors.[127]In late July 1945, most of the remaining large warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy were sunk inair attacks on Kure and the Inland Sea.By August 1945,Nagatowas the only survivingcapital shipof the Imperial Japanese Navy.[129]

Naval Infantryunits from 12th Air Fleet saw extensive action duringSouth SakhalinandKuil Islandscampaign inSoviet–Japanese War.[130]

Legacy

[edit]

Self-Defense Forces

[edit]Following Japan's surrender and subsequent occupation by theAlliesat the conclusion of World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy, along with the rest of the Japanese military, wasdissolvedin 1945. In the newconstitution of Japanwhich was drawn up in 1947,Article 9specifies that "The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes."[131]The prevalent view in Japan is that this article allows for military forces to be kept for the purposes of self-defense.[132]

In 1952, theSafety Security Forcewas formed within the Maritime Safety Agency, incorporating the minesweeping fleet and other military vessels, mainly destroyers, given by the United States. In 1954, the Safety Security Force was separated, and the JMSDF was formally created as the naval branch of the Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF), following the passage of the 1954 Self-Defense Forces Law. Japan's current navy falls under the umbrella of theJapan Self-Defense Forces(JSDF) as theJapan Maritime Self-Defense Force(JMSDF).[133][134][135][136][137][138][139]

See also

[edit]- Admiral of the Fleet (Japan)

- Carrier Striking Task Force

- Control FactionandImperial Way Faction– Army political groups about government reform

- Fleet FactionandTreaty Faction– Navy political groups about naval treaties

- Imperial Japanese Naval Academy

- Imperial Japanese Navy Armor Units

- Imperial Japanese Navy Aviation Bureau

- Imperial Japanese Navy bases and facilities

- Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors

- Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces

- List of Japanese Navy ships and war vessels in World War II

- List of weapons of the Japanese Navy

- May 15 Incident–coup d'étatwith Navy support

- Recruitment in the Imperial Japanese Navy

- "Strike South"and"Strike North"Doctrines

- Tokkeitai– Navy Military Police

Notes

[edit]- ^Library of Congress Country Studies,Japan> National Security> Self-Defense Forces> Early Development

- ^Evans, Kaigun

- ^Early Samurai: 200–1500 AD.Bloomsbury. 1991. p. 7.ISBN978-1855321311.[permanent dead link]

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 3.

- ^abcEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 4.

- ^Yosaburō Takekoshi.The economic aspects of the history of the civilization of Japan.1967. p. 344.

- ^THE FIRST IRONCLADSIn Japanese:[1]Archived2005-11-16 at theWayback Machine.Also in English:[2]Archived2019-11-17 at theWayback Machine:"Ironclad ships, however, were not new to Japan and Hideyoshi;Oda Nobunaga,in fact, had many ironclad ships in his fleet. "(referring to the anteriority of Japanese ironclads (1578) to the KoreanTurtle ships(1592)). In Western sources, Japanese ironclads are described in CR Boxer "The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650", p. 122, quoting the account of the Italian Jesuit Organtino visiting Japan in 1578. Nobunaga's ironclad fleet is also described in "A History of Japan, 1334–1615", Georges Samson, p. 309ISBN0804705259.AdmiralYi Sun-sininvented Korea's "ironclad Turtle ships", first documented in 1592. Incidentally, Korea's iron plates only covered the roof (to prevent intrusion), and not the sides of their ships. The first Western ironclads date to 1859 with the FrenchGloire( "Steam, Steel and Shellfire" ).

- ^Louis-Frédéric (2002).Japan Encyclopedia.Harvard University Press. p. 293.ISBN978-0674017535.

- ^Donald F. Lach; Edwin J. Van Kley (1998).Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 1: Trade, Missions, Literature.Vol. III. University of Chicago Press. p. 29.ISBN978-0226467658.

- ^Geoffrey Parker (1996).The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500–1800.Cambridge University Press. p. 110.ISBN978-0521479585.

- ^R. H. P. Mason; J. G. Caiger (1997).A History of Japan: Revised Edition.Tuttle Publishing. p. 205.ISBN978-0804820974.

- ^abcdefghEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 5.

- ^Sims 1998,p. 246.

- ^abcSchencking 2005,p. 15.

- ^abSchencking 2005,p. 16.

- ^Jentschura p. 113

- ^abcdeSchencking 2005,p. 13.

- ^abSchencking 2005,p. 11.

- ^abcdefEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 7.

- ^Sondhaus 2001,p. 100.

- ^abcdSchencking 2005,p. 12.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 9.

- ^abSchencking 2005,p. 19.

- ^abSchencking 2005,p. 18.

- ^abcEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 12.

- ^Sondhaus 2001,p. 133.

- ^Peter F. Kornicki (1998).Meiji Japan: The emergence of the Meiji state.Psychology Press. p. 191.ISBN978-0415156189.

- ^Chae-ŏn Kang; Jae-eun Kang (2006).The Land of Scholars: Two Thousand Years of Korean Confucianism.Homa & Sekey Books. p. 450.ISBN978-1931907309.

- ^abcSchencking 2005,p. 26.

- ^abcdefSchencking 2005,p. 27.

- ^abcSchencking 2005,p. 34.

- ^abcSchencking 2005,p. 35.

- ^abcdefghijEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 14.

- ^abcdSims 1998,p. 250.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 19.

- ^Jonathan A. Grant (2007).Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism.Harvard University Press. p. 137.ISBN978-0674024427.

- ^Howe, p. 281

- ^Sims 1998,p. 354.

- ^Chiyoda (II): First Armoured Cruiser of the Imperial Japanese Navy,Kathrin Milanovich, Warship 2006, Conway Maritime Press, 2006,ISBN978-1844860302

- ^abEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 38.

- ^Schencking 2005,p. 81.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 40.

- ^abcEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 41.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 42.

- ^abEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 46.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 48.

- ^Schencking 2005,p. 83.

- ^Stanley Sandler (2002).Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO. p. 117.ISBN978-1576073445.

- ^Arthur J. Alexander (2008).The Arc of Japan's Economic Development.Routledge. p. 56.ISBN978-0415700238.

- ^abcSchencking 2005,p. 84.

- ^abSchencking 2005,p. 87.

- ^abcEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 58.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,pp. 58–59.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 59.

- ^abcdeEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 60.

- ^abSchencking 2005,p. 88.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 65.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 52.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,pp. 60–61.

- ^CorbettMaritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War,2:333

- ^Schencking 2005,p. 108.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 116.

- ^Schencking 2005,p. 122.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 177.

- ^Howe, p. 284

- ^Howe, p. 268

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,pp. 150–151.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 84.

- ^abJentschura p. 23

- ^Jane'sBattleships of the 20th Century,p. 68

- ^Jentschura p. 22

- ^Wakamiya is "credited with conducting the first successful carrier air raid in history" AustrianSMSRadetzkylaunched sea plane raids a year earlier

- ^Peattie 2007,p. 9.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 168.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 161.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 169.

- ^Zammit, Roseanne (27 March 2004)."Japanese lieutenant's son visits Japanese war dead at Kalkara cemetery".Times of Malta.Retrieved25 May2015.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 212 & 215.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 191.

- ^Stille 2014,p. 12.

- ^abEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 194.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 193.

- ^Cambridge History of Japan Vol. 6.Ed. John Whitney Hall and Marius B. Jansen. Cambridge University Press, 1988

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 195.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 197.

- ^"Limitation of Naval Armament (FivePower Treaty of Washington Treaty)"(PDF).Library of Congress.

- ^Peattie 2007,p. 17.

- ^abcdEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 301.

- ^Peattie 2007,p. 19.

- ^"Sparrowhawk".www.j-aircraft.com.Retrieved2019-05-09.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 181.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 248.

- ^The British had used 18-inch guns during the First World War on the large "light" cruiserHMSFurious,converted to an aircraft carrier during the 1920s, and also two of the eight monitors of theLord Cliveclass,namelyLord CliveandGeneral Wolfe.

- ^Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed.The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare(London: Phoebus, 1978), Volum3 10, p. 1041, "Fubuki".

- ^Westwood,Fighting Ships

- ^LyonWorld War II Warshipsp. 34

- ^Peattie & Evans,Kaigun.

- ^Miller, Edward S.War Plan Orange.Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1991.

- ^Mahan, Alfred T.Influence of Seapower on History, 1660–1783(Boston: Little, Brown, n.d.).

- ^Peattie and Evans,Kaigun

- ^Miller,op. cit.The United States would be able to enforce a 60% ratio thanks to having broken the Japanese diplomatic code and being able to read signals from its government to her negotiators.Yardly,American Black Chamber.

- ^Peattie & Evans,op. cit.,and Willmott, H. P.,The Barrier and the Javelin.Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1983.

- ^LyonWorld War II warshipsp. 35

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 238.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 239.

- ^abEvans & Peattie 1997,pp. 243–244.

- ^abcdefEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 357.

- ^abEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 358.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 341.

- ^abcdEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 340.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 355 & 367.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 205 & 370.

- ^Howe, p. 286

- ^Stille 2014,p. 13.

- ^Stille 2014,p. 371.

- ^Parillo, Mark.Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II.Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1993.

- ^Drabkin, Ron; Kusunoki, K.; Hart, B. W. (22 September 2022)."Agents, attachés, and intelligence failures: The Imperial Japanese Navy's efforts to establish espionage networks in the United States before Pearl Harbor".Intelligence and National Security.38(3): 390–406.doi:10.1080/02684527.2022.2123935.ISSN0268-4527.S2CID252472562.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,p. 488.

- ^Stille 2014,p. 9.

- ^abcEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 489.

- ^Peattie 2007,p. 169.

- ^Peattie 2007,p. 172.

- ^Evans & Peattie 1997,pp. 490.

- ^abcdEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 491.

- ^Christopher Howe (1996).The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy: Development and Technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War.C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 313.ISBN978-1850655381.

- ^Peattie 2007,p. 188–189.

- ^abEvans & Peattie 1997,p. 492.

- ^Rikihei Inoguchi; Tadashi Nakajima; Roger Pineau (1958).The Divine Wind: Japan's Kamikaze Force in World War II.United States Naval Institute. p. 150.ISBN978-1557503947.

- ^Farley, Robert. "Imperial Japan's Last Floating Battleship". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^"Đệ 12 hàng không hạm đội"(in Japanese).RetrievedApril 21,2024.

- ^Menton, Linda K. (2003).The Rise of Modern Japan.University of Hawaii Press. p. 240.ISBN978-0824825317.

- ^Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution

- ^"Japan Self-Defense Force | Defending Japan".Defendingjapan.wordpress.com.Retrieved2014-08-03.

- ^"Hải thượng tự vệ đội: ギャラリー: Tả chân ギャラリー: Hộ vệ hạm ( hạm đĩnh )".Archived fromthe originalon 23 December 2014.Retrieved25 December2014.

- ^"Hải thượng tự vệ đội: ギャラリー: Tiềm thủy hạm ( hạm đĩnh )".Archived fromthe originalon 22 December 2014.Retrieved25 December2014.

- ^"Flightglobal – World Air Forces 2015"(PDF).Flightglobal.com.

- ^Thach, Marcel."The Madness of Toyotomi Hideyoshi".The Samurai Archives. Archived fromthe originalon 17 November 2019.Retrieved19 July2008.

- ^Samson, George (1961).A History of Japan, 1334–1615.Stanford University Press. p. 309.ISBN0804705259.

- ^Graham, Euan (2006).Japan's Sea Lane Security, 1940–2004: A Matter Of Life And Death?.Nissan Institute/Routledge Japanese Studies Series. Routledge. p. 307.ISBN0415356407.

References

[edit]- Dull, Paul S. (2013).A Battle History of The Imperial Japanese Navy(reprint 1978 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.ISBN978-1612512907.

- Boyd, Carl; Akihiko Yoshida (1995).The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II.Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.ISBN1557500150.

- Evans, David & Peattie, Mark R. (1997).Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941.Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.ISBN0870211927.

- Howe, Christopher (1996)The origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy, Development and technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War,University of Chicago PressISBN0226354857

- Ireland, Bernard (1996)Jane's Battleships of the 20th CenturyISBN0004709977

- Lengerer, Hans (September 2020). "The 1882 Coup d'État in Korea and the Second Expansion of the Imperial Japanese Navy: A Contribution to the Pre-History of the Chinese-Japanese War 1894–95".Warship International.LVII(3): 185–196.ISSN0043-0374.

- Lengerer, Hans (December 2020). "The 1884 Coup d'État in Korea — Revision and Acceleration of the Expansion of the IJN: A Contribution to the Pre-History of the Chinese-Japanese War 1894–95".Warship International.LVII(4): 289–302.ISSN0043-0374.

- Lyon, D.J. (1976)World War II warships,Excalibur BooksISBN0856132209

- Sims, Richard (1998).French Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan 1854–95.Psychology Press.ISBN1873410611.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001).Naval Warfare, 1815–1914.Routledge.ISBN0415214777.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977).Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy.Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute.ISBN087021893X.

- Jordan, John (2011).Warships after Washington: The Development of Five Major Fleets 1922–1930.Seaforth Publishing.ISBN978-1848321175.

- Peattie, Mark R(2007).Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909–1941.Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.ISBN978-1612514369.

- Schencking, J. Charles (2005).Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, And The Emergence Of The Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868–1922.Stanford University Press.ISBN0804749779.

- Stille, Mark (2014).The Imperial Japanese Navy in the Pacific War.Osprey Publishing.ISBN978-1472801463.

Further reading

[edit]- Agawa, Naoyuki (2019).Friendship across the Seas: The US Navy and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force.Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture. Archived fromthe originalon 2019-05-27.Retrieved2019-05-27.

- Baker, Arthur Davidson (1987). "Japanese Naval Construction 1915–1945: An Introductory Essay".Warship International.XXIV(1): 46–68.ISSN0043-0374.

- Boxer, C.R. (1993)The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650,ISBN1857540352

- D'Albas, Andrieu (1965).Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II.Devin-Adair Pub.ISBN081595302X.

- Delorme, Pierre,Les Grandes Batailles de l'Histoire, Port-Arthur 1904,Socomer Editions (French)

- Gardiner, Robert (editor) (2001)Steam, Steel and Shellfire, The Steam Warship 1815–1905,ISBN0785814132

- Hara, Tameichi(1961).Japanese Destroyer Captain.New York & Toronto:Ballantine Books.ISBN0345278941.

- Hashimoto, Mochitsura (2010) [1954].Sunk: The Story of the Japanese Submarine Fleet, 1941–1945.New York: Henry Holt; reprint: Progressive Press.ISBN978-1615775811.

- Lacroix, Eric; Linton Wells (1997).Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War.Naval Institute Press.ISBN0870213113.

- Nagazumi, Yōko ( vĩnh tích dương tử )Red Seal Ships ( chu ấn thuyền ),ISBN4642066594(Japanese)

- Polak,Christian. (2001).Soie et lumières: L'âge d'or des échanges franco-japonais (des origines aux années 1950).Tokyo:Chambre de Commerce et d'Industrie Française du Japon,HachetteFujin Gahōsha (アシェット phụ nhân họa báo xã ).

- Polak,Christian. (2002). Quyên と quang: Tri られざる nhật phật giao lưu 100 niên の lịch sử ( giang hộ thời đại 1950 niên đại )Kinu to hikariō: shirarezaru Nichi-Futsu kōryū 100-nen no rekishi (Edo jidai-1950-nendai).Tokyo: Ashetto Fujin Gahōsha, 2002.ISBN978-4573062108;OCLC50875162

- Seki, Eiji. (2006).Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940.London:Global Oriental.ISBN978-1905246281(cloth) [reprinted byUniversity of Hawaii Press,Honolulu, 2007 –previously announced asSinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation.]

- Tōgō Shrine and Tōgō Association ( đông hương thần xã ・ đông hương hội ),Togo Heihachiro in images, illustrated Meiji Navy( đồ thuyết đông hương bình bát lang, mục で kiến る minh trị の hải quân ), (Japanese)

- Japanese submarinesTiềm thủy hạm đại tác chiến, Jinbutsu publishing ( tân nhân vật 従 lai xã ) (Japanese)

External links

[edit]- Imperial Japanese Navy

- Disbanded navies

- Empire of Japan

- Military of the Empire of Japan

- Naval history of Japan

- 1869 establishments in Japan

- 1945 disestablishments in Japan

- Military units and formations established in 1869

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1945

- Attack on Pearl Harbor

- Naval history of World War II

![The gunboat Chiyoda, was Japan's first domestically built steam warship. It was completed in May 1866.[16]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/Gunboat_Chiyodagata_anchored_at_Yokosuka.png/120px-Gunboat_Chiyodagata_anchored_at_Yokosuka.png)