Independence or Death(painting)

| Independence or Death | |

|---|---|

| Cry of Ipiranga | |

| |

| Artist | Pedro Américo |

| Year | 1888 |

| Medium | oil paint |

| Dimensions | 415 cm (163 in) × 760 cm (300 in) |

| Location | Museu do Ipiranga,São Paulo,Brazil |

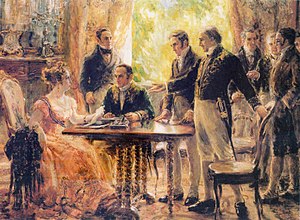

The 1888 paintingIndependence or Death(Independência ou Mortein Portuguese), also known as theCry of Ipiranga(Grito do Ipirangain the original) is an oil on canvas painting byPedro Américo,from 1888. It is the best known artwork representing theproclamationof theBrazilian independence.[1]

Author

[edit]

Pedro Américowas born in 1843, in theParaíba ProvinceofBrazil,more specifically in the now municipality ofAreia,at the time the small town ofBrejo d'Areia.Since his youth, he showed a vocation for painting, being 10 years old when he participated as a drawer of flora and fauna in a scientific expedition through Northeastern Brazil led by the FrenchnaturalistLouis Jacques Brunet. At approximately 13 years old, he entered theImperial Academy of Fine Arts,in the city ofRio de Janeiro.His performance at the academy made him known even toEmperor Pedro II,who sponsored a trip toParisand studies at theÉcole nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts,where the artist perfected his style, mainly inhistorical painting.His most famous work,Independence or Death(Portuguese:Independência ou Morte), was shown for the first time in theAccademia di Belle Arti di Firenze(Academy of Fine Arts of Florence) on April 8, 1888. After going to Brazil, remaining there for a few years, he returned toFlorence,where he died in 1905.[2][3]

Context

[edit]Pre-execution agreements

[edit]Contrarily to what is speculated, Pedro Américo was not invited to execute the painting dedicated to the independence: the artist himself offered to do it. In 1885, according to records made by imperial adviserJoaquim Inácio Ramalho,Américo declared to the commission of works, that he would charge himself with making a historical painting in memory of the glorious act ofPrince Regent Pedro,proclaiming theBrazilian independence.[4]Américo's proposal was not immediately accepted, due to a lack of funds and the architecture of the building that would in the future become theMuseu Paulista.In December of the same year, the newspaperA Província de São Paulopublished an article criticising the government's behaviour, accusing it of giving false hopes to the artist, considered at the time a master of aesthetics.[4]

It is thought that the media's provocations caused the panel in charge of approving or rejecting Américo's request to change its mind. Towards the end of December 1885, Pedro Américo receives a letter from Ramalho accepting his offer.[4]

In a contract signed on July 14, 1886, between Pedro Américo e Ramalho,[2]at the time president of the Commission of theMonument to the Independence of Brazil,the artist committed himself to painting, accordingly to the description of the documents, a "commemorative historical painting of the proclamation of independence by prince regentD.Pedro in the fields ofYpiranga"(Portuguese:"quadro histórico comemorativo da proclamação da independência pelo príncipe regente D. Pedro nos campos do Ypiranga"). The deadline for the painting of the work would be three years, and Américo would be paid thirtycontos de réis,in addition to the sixcontosthat the artist received when he signed the contract, money destined to the first studies and preparatory activities for the work.[4]Entirely painted inFlorence,it was finished a year before due, in 1888.[2]

History

[edit]

Américo finished the painting in 1888 inFlorence,Italy, 66 years after the proclamation of independence. TheBrazilian imperial housecommissioned the work, due to investments into the construction of the Museu do Ipiranga (presently theMuseu Paulista[5]). The goal of the artwork was to emphasize the monarchy.[1]

Controversy

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(September 2021) |

There exists evidence that the painting is not an accurate description of the events on the shores of theIpiranga Brook.[1]

Plagiarism accusation

[edit]Pedro Américo as a copier

[edit]

The painting by Pedro Américo can be compared with other works made by different artists. That resulted in plagiarism accusations to the painter. In his work, Américo creates a dialogue between art history and the traditional battle paintings that emphasised the hero (previously made by his teachers). The process of making the painting was complex.[6]The dialogue with historical paintings was well regarded by the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, in addition to being a technique used by many artists, without being considered a copy. He intended to develop an image that reminded of those works from the past accordingly to the techniques that were used by those artists.[7]

The experience he had 10 years earlier, with his workBatalha do Avaí,that was not well received by critics, classifying it as "anti-academical" (Portuguese:antiacadêmica), made him study in more depth aesthetic topics and publish the literary workDiscurso Sobre o Plágio na Literatura e na Arte(Discourse On Plagiarism in Literature and Art) in 1879, years before beginningIndependência ou Morte.[8]

The works by French paintersJean-Louis Ernest MeissonierandHorace Vernetwere used as sources forIndependência ou Morte.Américo studied the worksNapoleon IIIat theBattle of Solferino(1863) and1807,Friedland(c. 1870), both by Meissonier and alsoBataille de Friedland, 14 juin 1807(c. 1850), by Vernet. There are similarities between the paintings: the confrontation between D. Pedro and the soldiers to the right has composition similar to the structure of1807, Friedland:the concentration of people in both paintings is similar;[4]the elevation of D. Pedro to a higher point in the topography approaches the work of Américo to those of Meissonier. In addition, it can be deduced that Américo wished to portray D. Pedro as astatesman,as can be noticed when analysing the figure of Napoleon in the work of Meissonier.[6]

The historianLilia Moritz Schwarczquotes in his bookBatalha do Avaí – A Beleza da Barbárie(Battle of Avaí - The Beauty of Barbarism), that the critics of the work by Pedro Américo saw in bothA Batalha do Avaí,as inIndependência ou Morte,two "brazen" (Portuguese:"descarados") cases of plagiarism of the paintersAndrea Appianiand Ernest Meissonier, respectively. According to the historian, the critics saw inIndependência ou Morte,a whole scene copy of1807, Friedland,painted thirteen years earlier by Meissonier, "in which he also portrays Napoleon, a polyvalent figure that serves as a model for Américo to paint both Caxias and D. Pedro I, this one giving the cry of independence at the bank of theIpiranga"(Portuguese:"em que este também retrata Napoleão, figura polivalente que tanto serve de modelo para Américo pintar Caxias como D. Pedro I, este dando o grito de independência às margens do Ipiranga.").[9]

According to theart historianMaraliz de Castro, the work by Américo has major differences from the paintings by Meissonier, saying the Brazilian concerns himself with every detail, searching for a balance between all the elements, with the goal of creating a significant impression of unity, while inNapoleon IIIat theBattle of Solferino,the Frenchman wished to simulate an instantaneous photography of reality differently from the carefully organised figures inIndependência ou Morte.According to Maraliz, another difference is the movement in the painting by Meissonier: the soldiers run frenetically in direction to the viewer; however Américo composes a form in ellipsis to make up all the characters of the scene, uniting them to the use of perspective.[10]In the other hand, according to the art historian Cláudia Valladão, these details reaffirm the traditional values of Américo, as however he agreed with the group of theoreticians at the time called "idealists", his artistic position was directed at a dialogue with the "realist" tendencies of historical painting, as used by a variety of artists at the time, for example Meissonier.[11]There was also an contemporary accusation of plagiarism published in 1982 by the journalistElio Gaspari,in his column in the magazineVeja,also refuted by Cláudia Valladão, that comments on the publication: "accusing Pedro Américo of plagiarism is not understand the assumptions of his art" (Portuguese:"acusá-lo [Pedro Américo] de plágio é não compreender os pressupostos de sua arte" ).[12]

Inspiration pictures

[edit]Pedro Américo used some historical paintings as references to compose the artworkIndependência ou Morte.[7]

Comparing Américo's painting withA Proclamação da IndependênciabyFrançois-René Moreaux,one realizes that the latter includes many more civilians than the Brazilian in his artwork. The characters in Moreaux's painting look at the sky. Consequently, the emperor is portrayed as a figure fulfilling a divine will by proclaiming independence, not as someone with leadership and political abilities, as done by Américo.[6]

In contrast, the worksIndependência ou MorteandRetrato de Deodoro da Fonsecafrom the painterHenrique Bernardelli(which represents the officer declaring the end of the monarchy and the beginning of the republic in Brazil) complete one another: both complied to the interests of the 1889 republic and reaffirmed that historical changes in Brazil were marked by heroes and grandiose events. They illustrate independence and are effective in its propaganda, even if they don't question the new Brazilian autonomy with veracity.[13]

Furthermore, Bernardelli's painting portrays the event in an epic and idealized manner, as in Pedro Américo's artwork.Deodoro,in reality, was sick and constantly bed-ridden, with a chronic lack of air caused byArteriosclerosis.Accordingly, to reports by the lawyerFrancisco Glicério,who participated in theProclamation of the Republic,the marshal barely had enough strength to put on his uniform. Unlike what is shown in the painting, he was weak and staggering, not being able to stay on top of his horse.[14]

Legacy

[edit]Diffusion in didactic books, monuments and digital media

[edit]The painting by Pedro Américo appears constantly in Brazilian didactic books, therefore becoming a "canonical image" (Portuguese:"imagem canônica") in the teaching of history in Brazil.[15]A study with children has shown that in part due to the influence of the illustrations in didactic books, they represented the act of independence inspired by the graphical reference ofIndependência ou Morte.[16]In the books, the painting is used to illustrate the act of founding the Brazilian nationality, showing that the transition to independence is the result of a cry.[17]That common interpretation, represents the cry of Ipiranga as a direction, in a personalised act and centralised in the monarch.[18]

The importance of the work by Pedro Américo, the official portrayal of independence, resulted in it influencing other works, among which the pediment of theMonument to the Independence of Brazil,which emulates the work of Américo.[19]

The painting by Pedro Américo is part of the collection available in the projectGoogle Arts & Culture.[20]The work was digitalised as agigapixel imagewith Google's Art Camera, to record details in the work that are imperceptible to the naked eye.Independência ou Morteis the largest painting to be digitalised by Google in Brazil.[21][22]

Influence on painting

[edit]The work by Pedro Américo became the reference, sometimes to be deconstructed, of the portrayal of Brazilian Independence. Creating an alternate version to that of the heroism and triumphalism of Dom Pedro, portrayed by Américo, set the tone, for example, for the production of highlighted works in expositions celebrating theIndependence Centenary,asSessão do Conselho de Estado(Session of the State Council), byGeorgina de Albuquerque,andPrimeiros Sons do Hino Nacional(First hearing of Independence Anthem), byAugusto Bracet.In the painting by Albuquerque, the protagonist of the declaration of independence becomesMaria Leopoldina,in a scene where she is shown deliberating with theCouncil of the Attorneys-general of the Provinces of Brazilthe direction to Dom Pedro to end the colonisation of Brazil by Portugal; in the painting by Bracet, Dom Pedro appears as the protagonist of the separation from Portugal, but in a domestic setting and in a jovial attitude, composing theHino da Independência(Independence Anthem).[23]

Notes

[edit]- ^abc"O grito do Ipiranga aconteceu como no quadro?".uol.com.br. Archived fromthe originalon October 4, 2012.RetrievedNovember 2,2012.

- ^abc"Pedro Américo".UOL Educação. Archived fromthe originalon April 27, 2018.RetrievedApril 28,2018.

- ^"Pedro Américo".Britannica Escola. Archived fromthe originalon April 27, 2018.RetrievedApril 28,2018.

- ^abcdeOliveira & Mattos 1999.

- ^"Quadro de Pedro Américo de Figueiredo" Independência ou Morte "".Archived fromthe originalon November 13, 2013.RetrievedNovember 13,2013.

- ^abcSchlichta 2009.

- ^abFranco 2008.

- ^Oliveira & Mattos 1999,p. 115.

- ^Filho, Antonio G. (December 13, 2013)."Lilia Schwarcz investiga o lado republicano da tela de Pedro Américo".O Estado de S. Paulo. Archived fromthe originalon January 18, 2017.RetrievedMay 20,2018.

- ^Christo 2009.

- ^Oliveira & Mattos 1999,p. 126.

- ^Oliveira & Mattos 1999,p. 97.

- ^Souza 2000.

- ^Gomes, Laurentino (2014)."Dois cavalos que mudaram a História do Brasil".El País.

- ^Bueno 2013.

- ^Purificação 2002,pp. 31–40.

- ^Neto 2017,p. 114.

- ^Neto 2017,p. 115.

- ^Andrade 2016,p. 147.

- ^Braziliense, Correio (September 11, 2018)."Acervo do Museu Paulista da USP passa a colaborar com o projeto Google Arts".Correio Braziliense(in Brazilian Portuguese).RetrievedDecember 29,2018.

- ^"Museu Paulista da USP está digitalizado na plataforma da Google - Arte".Canaltech(in Brazilian Portuguese). September 10, 2018.RetrievedDecember 29,2018.

- ^"Retorno online do Museu do Ipiranga www.jb.com.br - País".www.jb.com.br.RetrievedDecember 29,2018.

- ^Cavalcanti Simioni 2014.

References

[edit]Books and theses

[edit]- Oliveira, Cecilia Helena de Salles; Mattos, Claudia Valladão de (1999).O Brado do Ipiranga.São Paulo: Edusp.ISBN978-85-314-0518-1.

- Souza, Iara Lis Carvalho (2000).A Independência do Brasil.Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar.ISBN9788537807545.

- Lima, Oliveira (1997).O Movimento da Independência, 1821-1822.Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks.

- Américo, Pedro(1888).Alguns discursos do Dr. Pedro Americo de Figueiredo(PDF).Florença: Imprensa de l'Arte della Stampa.(Work in the public domain)

- Schlichta, Consuelo Alcioni Borba Duarte (2006).A pintura histórica e a elaboração de uma certidão visual para a nação no século XIX(tese doutorado). Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná. Archived fromthe originalon July 8, 2018.RetrievedMay 25,2018.

- Franco, Pablo Endrigo (2008).O riacho do Ipiranga e a independência nos traços dos geógrafos, nos pincéis dos artistas e nos registros dos historiadores (1822-1889)(Mestrado). Universidade de Brasília.

- Purificação, Ana Teresa de Souza e Castro da (December 18, 2002).(Re)criando interpretações sobre a Independência do Brasil: um estudo das mediaçoes entre memória e história nos livros didáticos(Mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo.doi:10.11606/D.8.2002.tde-18092003-193651.

- Andrade, Fabricio Reiner de (March 5, 2016).Ettore Ximenes: monumentos e encomendas (1855-1926)(Mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo.RetrievedMay 22,2018.

- Castro, Isis Pimentel de (2007).Os pintores de história: a relação entre arte e história através das telas de batalhas de Pedro Américo e Victor Meirelles(Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.RetrievedMay 22,2018.

Journals

[edit]- Schlichta, Consuelo Alcioni B. D. (2009). "Independência ou Morte (1888), de Pedro Américo: A pintura histórica e a elaboração de uma certidão visual para a nação".ANPUH – XXV Simpósio Nacional de História.

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz(2009)."Paisagem e Identidade: A construção de um modelo de nacionalidade herdado do período joanino".Revista Acervo.22(1).ISSN2237-8723.RetrievedMay 22,2018.

- Mattos, Claudia Valladão de (1999)."Da Palavra à Imagem: sobre o programa decorativo de Affonso Taunay para o Museu Paulista".Anais do Museu Paulista.6(1).RetrievedMay 22,2018.

- Christo, Maraliz de Castro Vieira (2009)."A pintura de história no Brasil do Século XIX: Panorama introdutório".Arbor.187(740).RetrievedMay 22,2018.

- Bueno, João Batista Gonçalves (August 8, 2013)."Tecendo reflexões sobre as imagens pictóricas (do final do século XIX e início do século XX) utilizadas nos livros didáticos no Brasil".Fóruns Contemporâneos de Ensino de História No Brasil On-Line.1(1). Archived fromthe originalon May 11, 2018.RetrievedJanuary 28,2020.

- Neto, José Batista (July 7, 2017)."A Problemática do Ensino da História nos Textos e nas Imagens dos Livros Didáticos".Tópicos Educacionais.13(1–2).ISSN2448-0215.

- Cavalcanti Simioni, Ana Paula (April 2, 2014)."Les portraits de l'Impératrice. Genre et politique dans la peinture d'histoire du Brésil".Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos(in French).doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.66390.ISSN1626-0252.

- Oliveira, Emerson Dionisío Gomes de (July 2008)."Fragmentos de cumplicidade: arte, museus e política institucional".Métis: História e Cultura.7(13). Universidade de Caxias do Sul.ISSN2236-2762.RetrievedMay 22,2018.

- Almeida, Rodrigo Estramanho de (2017).História e política do Brasil na pintura de Pedro Américo.9.º Congresso Latino-Americano de Ciência Política.RetrievedMay 22,2018.

- Giordani, Laura (2016).O grito do Ipiranga: a independência do Brasil das galerias aos quadrinhos(PDF).XIII Encontro Estadual de História da ANPUH RS: Ensino, direitos e democracia.RetrievedMay 22,2018.

External links

[edit] Media related toCategory:Independence or Death by Pedro_Américoat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toCategory:Independence or Death by Pedro_Américoat Wikimedia Commons- "O Brado do Ipiranga: a cena que Pedro Américo imaginou para o Brasil".Canal Ciência USP no YouTube(in Brazilian Portuguese).RetrievedMay 24,2018.

- "The Independence of Brazil on canvas: Creating an Image".Google Arts & Culture.RetrievedDecember 29,2018.